Figure 8

Learning through balancing risk with competence

The principal focus at first contact is to engage participants in the adventure learning session, to draw them out of themselves because leading participants is a process of influence and encouragement. Very quickly, at the start of the engagement, the adventure learning instructor has a lot to do; they have to evaluate the mood, abilities, focus and interactions of the group, and simultaneously there are routine administrative tasks, such as checking consent forms, finding out if any participants have particular conditions of which the instructor should be aware (asthma, diabetes, heart conditions, mobility issues) and issuing any equipment. At the same time the participants will be excited or anxious, wanting to know what is in store for them, where they can change, where the toilets are, where they can get a drink, and so on; they will be asking questions, chattering, wanting to explore. The first few minutes of an adventure learning session are frenetic and a lot has to be accomplished; the instructor has to be prepared, organised and not disengage the participants by being snappy or ignoring them, while getting necessary tasks done so that they can deliver a safe and enjoyable session.

Adventurous activities can engage and stimulate the most recalcitrant young person by providing adrenalin ‘rushes’ akin to those of less socially acceptable activities; the aim of adventure is to capture the imagination and harness energy. The informal learning principle of working with rather than on people allies with the adventure concept of challenge by choice: participants impelled not compelled to participate, able to withdraw or decline participation if they so wish. This gives participants ownership over the engagement, empowering them to make an informed choice. The decision to engage is embedded in motivation; for motivation to exist, participants have to believe in themselves and their ability to achieve, and the associated learning from an adventure encounter has to have meaning to them personally in a context beyond that of the immediate learning situation. Yet challenge by choice has itself to be managed by the adventure learning instructor. The decision to decline participation has to be questioned, the instructor has to explore why the person is not participating. Quite often, the reason is simple nerves, not wanting to be seen to fail or ‘in group’ relationships are not positive.

The instructor has to encourage participation, gentle persuasion can be powerful and realising ‘having a go’ does not mean immediate expected aptitude is often enough. An instructor should never be forceful and demand participation, but equally must be persistent and persuasive.

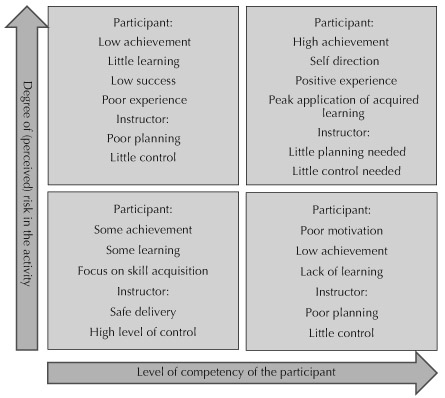

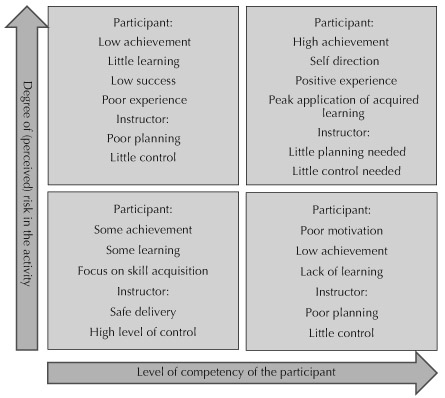

First impressions are really important, so the initial introduction (briefing) to the activity is fundamental in building anticipation and preparing participants for what is to come. The challenge for the instructor is to create the sense of challenge and to inspire participants to want to take part fully and achieve the set challenge, be that individually or as a group. As the session proceeds, the participants will hit difficulties and may not achieve the goal the first time, perhaps not even the second, third or fourth time; the point is that they should be inspired to want to carry on and keep trying. The instructor supports this by appreciative facilitation, which essentially means focussing on what the individual or group get right, not what is going wrong. The participants will be spending enough time getting frustrated at themselves and will be looking at what is not working, the art of the adventure learning instructor is to re-focus their minds on the positives, what is working well and where they are succeeding. This maintains the motivation to persevere when the adventure challenge becomes difficult. Adventure has an inherent perception of risk and danger and the challenge should stretch the participants, so for maximum outcome, the adventure learning instructor must balance (perceived) risk with competence (see Figure 8); the higher the level of risk at low competency, the less success can be achieved; the greater the degree of competency, the less risk is apparent and the achievements become more rewarding.

Figure 8 highlights how the interaction of competence and (perceived) level of risk bring about the quality of the experience. As the individual moves from initial experience (low risk, low competence) to self-directed learning (high risk, high competence), they become less reliant on the instructor and the potential rewards are that much greater. There is a point at which the participant engagement matches the instructor input and learning is maximised. It could be said that Figure 8 represents also the interaction of the individual with their environment, as competence is an individual concept concerning personal capacity, mood and skill and risk is an environmental concept concerning the environment, the challenge and the complexity of the challenge.

Rarely does a participant engage in adventure learning alone, more often engagement is in the context of a group. Groups evolve through a developmental process to develop a dynamic (Tuckman, 1965). There is a strong argument that people will learn through interaction (Bandura 1977), as people watch one another, mimic one another and (sub)consciously develop their way of being. The development of this culture is the basis of collective cohesion that defines the way that the participants face the activity (and the instructor); it can be positive and lead to success or it can become misdirected and need subsequent refocus. Participants are individuals, each with their own character, narrative and emotions; yet they are going to arrive as a part of a group. The instructor has to develop an ability to treat the participants equally, making a rapid assessment of their abilities, but without stereotyping them unfairly. Gender, cognitive ability, physical ability, medical conditions, past adventure experience, culture and ethnicity can all affect the interaction of the participants with each other, as well as the leader. At all times the leader has to be aware of their language and body language, and the effect these can have on the group.

Figure 8

Learning through balancing risk with competence

Bandura, A. (1977) Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.