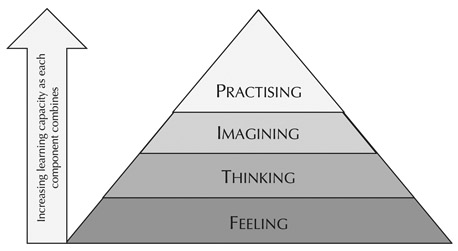

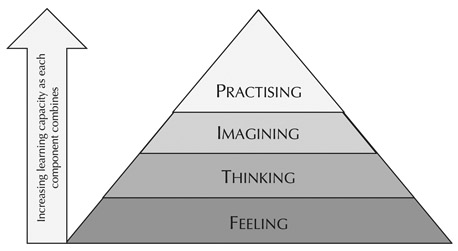

Figure 1

Increasing learning capacity by increasing the senses engaged

Traditional education is behaviourist, requiring that the learner sit at a desk in a classroom while a teacher delivers; the assumption is that the learner is ‘an empty vessel where the teacher’s role is to fill it with knowledge’ (Allison and Pomeroy 2000). There are many who advocate that education should cultivate the moral, emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual dimensions equally, a perspective known as holism. A holistic way of thinking seeks to encompass and integrate multiple layers of meaning and experience; in other words, seeks to recognise every aspect of a person’s life and experience rather than dictates a particular way of being or thinking. We are all unique individuals, with our own experiences and characteristics; our intelligences and abilities are far more complex than our examination results. Holistic education seeks to create an intrinsic reverence for life and a love of learning, advocating there is no single best way, but many paths of learning that recognise and respect the fact that we are all different.

The foundation of holistic learning is that we, as people, are comprised of a complex and intricate combination of elements – intellect, emotion, motivation, intuition, imagination – and we most effectively learn or progress when all of these are activated and stimulated. There are four modes of psychological being (emotional welfare) that govern the way we think, the way we feel, how we imagine and how we live, which may engage singly or may engage in progressively synchronous partnership. Often we feel before we think and we think before we visualise the outcome; it is only when we have reconciled ourselves to each one and developed an understanding of how each is driven within us, can we practice (or live) in a balanced manner, understanding our emotions and controlling them. Having emotional control and understanding ourselves helps us to learn by allowing us the psychological capacity to become open, receptive to new knowledge. Figure 1 shows the hierarchy of emotions whose incremental synergy establishes the basis of open-mindedness and capacity to develop.

Holistic learning looks to build associations between data items into a network of information chains. These associations develop an underlying understanding (a construct) that can form the basis of a problem-solving solution. Holistic learning proposes that when all of our core elements are working, the overall result is better than if only one is engaged (synergy). This contrasts sharply with much mainstream traditional education thinking, where the focus is on intellect, classroom theory and examinations. Traditional (behaviourist) learning relies heavily on rote learning and the memorisation of facts. This encourages ‘silos’ to form in the brain, lots of separate packets of learned knowledge that are not related to one another, nor are they seen as applicable to anything other than the context in which they were learned. By presenting learning as an holistic methodology, the emphasis moves from a focus on the teacher at the core to the relationship of the learner with the learning situation being the heart of the process, meaning becomes embedded in the process and has an emotional, personal influence on the learner. Every experience has a legacy, adding to how we think and respond in the future, so each aspect of a planned learning experience should exist within a framework that defines and measures capacity, making links between feelings and learning, thereby enabling the learner to identify with their learning, absorb it and apply it elsewhere.

Figure 1

Increasing learning capacity by increasing the senses engaged

Holistic learning is the acquisition of cross-curricular knowledge through experiential and multi-modal methods, while developing personally and socially.

In simple terms, this means combining ‘delivered’ learning (classroom style) with ‘discovered’ learning (practical experience) so that the person can see, hear, read and put into practice the learning in a social environment (in a group). Rather than school education being shaped by a timetable of discrete subjects taught in isolation, the interrelationship of subjects and their influence on one another enables an holistic (cross-curricular) syllabus.

It is often said that we learn better by seeing and doing than by reading or hearing; it is also said that today’s modern world is so full of external stimuli that the average concentration span is decreasing. Most people probably can’t remember what they learned in school, unless they have applied it directly to areas of their life, profession and possibly taught it to others. Is that because we genuinely only retain a fraction of what is read or heard? In reality yes, but the reason is less to do with the our ability to concentrate and our brain’s capacity to retain information than it is to do with the fact that learning becomes ingrained by it meaning something to us personally and having to engage some degree of effort in acquiring it. The traditional belief among neuroscientists has been that the five senses operate largely as independent systems. However, research suggests that the interaction of the five senses (sight, hearing, smell, touch, taste) are the rule, rather than the exception, so logically the more senses we use in learning and in practising what has been learned, the more pathways are available for embedding the learning and recalling it when necessary.

We are born to learn, the brain has evolved as a machine to explore and learn throughout its lifetime. As humans, we are endowed with the capacity and inescapable impulse to learn, not necessarily as a conscious act, but as a lifelong process of absorbing and transforming experiences, observations and influences into knowledge, skills, behaviours and attitudes. Thus, learning does not necessarily derive from being in a classroom, but allowing the brain to absorb its environment, process it and transform it into learning. In structured learning environments, this can be supported and directed by an instructor. Natural selection has resulted in our brains being able to process data and solve problems in changing environments; when we learn and understand something of meaning to us that we can apply elsewhere and in a different situation, the reward pathway in the brain is activated and gives us a jolt of pleasure (dopamine) so that we will remember and repeat the action when necessary or desired. If the result of the application of learning is something other than what we expect, we are deprived of the dopamine reward, so we learn that application is inappropriate and remember it. Depending on the outcome we do get, either we remember never to try the application again, or we try the application in a different context or situation.

Understanding the way we respond physiologically, we can begin to understand how we learn and then use this to make learning experiences, whether for ourselves or others, deeper and more meaningful, making sure that the maximum amount is derived from each learning opportunity.

Adventure learning is holistic in a number of ways:

Adventure learning is not only holistic in enabling use of all the senses; it also requires a physical input, introducing potential further dimensions. This means adventure learning offers an opportunity for lateral learning, to introduce health understanding into the learning equation. In learning and understanding the self, we begin to understand about our drives, our strengths and our weaknesses. This creates a realisation of how we can manage these and gain control of our lives; if we know what makes us happy or causes us distress, we have the ability to direct our lives and our actions accordingly. Programmes can address nutrition and the value of exercise; learning about the body physically and psychologically helps learners understand the value of personal health and how to make the best of themselves.

People learn differently, we all know that, learning can be both a personal and a social process. A lot of literature has been written about learning styles and how we all have a tendency towards one or another (Honey and Mumford 1982; Kolb 1984), but these all assume we only learn in one way. People are complex beings, comprised of a multitude of abilities, which are partially recognised by the theory of multiple intelligences (Smith 2008), but this is still not an accurate reflection of human learning. The reality is that we learn in different ways at different times of the day and of life, according to mood and environment. We are also influenced by the people around us, often copying people we admire or unconsciously aping those with whom we most often socialise. The roles of intentions, choice and decision-making also cannot be underestimated in why and how we learn or act. Adventure learning offers learning in different ways; it is visual and physical; it does not rely on books. While the instructor needs to know and understand the underpinning theory, the participant does not. The instructor must understand the different styles of learning and how to apply them to best effect, as this adds to the ‘toolkit’ of delivery and to their understanding for developing a programme. Unless it is an aspect of their learning, the learner does not need to know the style applied, simply benefit from the planning and knowledge of the instructor. The art of the skilful instructor is to make a session appear spontaneous and naturally occurring, when it is in fact meticulously planned!

The varied sensory nature of adventure learning provides learning opportunities for people less able to cope with the confines of the classroom. Young people with dyslexia or attention deficit disorder are able to use their stronger senses, such as sight, to understand what is being taught. The ability to learn in a different way opens their world and enables them to operate at the same level as their peers; other (innate) capabilities can come to the fore, such as leadership skills, problem solving or group roles. Having dyslexia or attention deficit disorder does not have to be a barrier to achieving; they are not disabilities but simply mean the brain focuses differently and prefers a different way of absorbing data.

As young people, we have no choice but to take part in school games lessons, yet many young people are not interested in traditional school sport, mainly because if we are not too good at it, we feel self-conscious or become reluctant to participate. For many of us, the idea of running around after a football or a hockey puck does not inspire us in the slightest and as we enter our teenage years we become very aware of ourselves and how we appear. For young women especially, appearance is an integral part of who and what we are; putting it back to ancestral, stone age terms, appearance meant attracting a mate and thus personal survival. This instinct remains inbred in our psyche. Adventure learning offers different sports to try, such as archery, climbing, cycling, mountain biking, kayaking and canoeing. Not only are these intensely physical, they do not necessarily rely on team interaction but can be undertaken in a group setting but achievement is much more about personal capacity and inclination. All these are also Olympic activities, with substantial opportunities for progression if potential and willingness are demonstrated. There is a growing obesity ‘epidemic’ in the western world that has to be addressed. Providing a range of alternatives to foster an interest in activities and a desire to engage on a regular basis is just one means of doing that and can create wider opportunities, such as joining clubs, making new friends and opening further progressive opportunities.

Allison, P. and Pomeroy, E. (2000) How shall we ‘know’? Epistemological concerns in research in experiential education. Journal of Experiential Education 23(2): 91–97.

Belbin, R. M. (1993) Team Roles at Work. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann.

Honey, P. and Mumford, A. (1982) Typology of learners. In their Manual of Learning Styles. London: Peter Honey Publications.

Kolb, D. A. (1984) Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source for Learning and Development. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Smith, M. K. (2008) Howard Gardner, multiple intelligences and education. Available at www.infed.org/mobi/howard-gardner-multiple-intelligences-and-education.