Figure 3

Maslow’s pyramid (hierarchy) of needs

Adventure learning has applicability for people of all ages, interests, abilities, lifestyles, environments and occupations. Whatever their cultural, ethnic or environmental background and circumstances, people can learn through adventure, in other words from trying something new. All cultures have an associated philosophy derived from generations of discovery, experience, thinking and theory; both Eastern and Western philosophies are similar in that they concern themselves with human existence, but diverge on their principles and concepts.

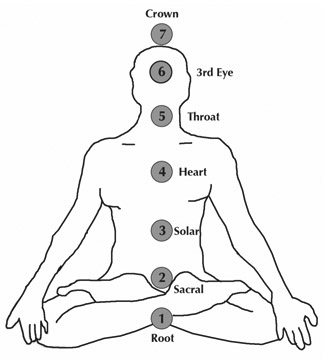

Western philosophy looks to a scientific base, with positivist, rational, logical explanations; Western society concerns itself with finding and proving an absolute ‘truth’. Life in the West tends to be focused on materialism and centralises the individual, with a clear linear view, based on the Christian philosophy that everything has a beginning and an end; people are driven by individual motives and the search for personal fulfilment. The Western mind-set is most clearly represented by Abraham Maslow (Maslow 1943) and is commonly represented as a pyramid (Figure 3).

Known as the pyramid (or hierarchy) of needs, Maslow (Maslow 1943) argues that there is an order to needs and we are motivated by each in turn; thus lower level needs (survival, security) must be satisfied before we can work on satisfying higher level (personal growth) needs. Maslow identified the lower level needs as ‘deficit’ needs (if the needs are not met, we are uncomfortable) and the higher level needs as ‘growth’ needs (we can never get enough of these and are constantly going to be motivated to meet them). If the conditions satisfying lower needs are removed, we regress down the pyramid to satisfy these needs again.

Eastern philosophy has a more subjectivist basis, where people exist as a part of a natural world that has no particular rules but simply is; Eastern society seeks to find ‘balance’, accepting that truth is given and need not be incontrovertibly proven. Life in the East is spiritual, where all events and entities are perceived as interconnected and life is a journey towards becoming part of that interconnectedness through self-knowledge and understanding. Any regularity in the world is the way people organise and understand their experience, not a proven truth; Eastern philosophy prescribes the nature of reality as being discovered through direct and unplanned experience. The Eastern mind-set is most clearly understood through the ‘chakra’ system (Figure 4).

Figure 3

Maslow’s pyramid (hierarchy) of needs

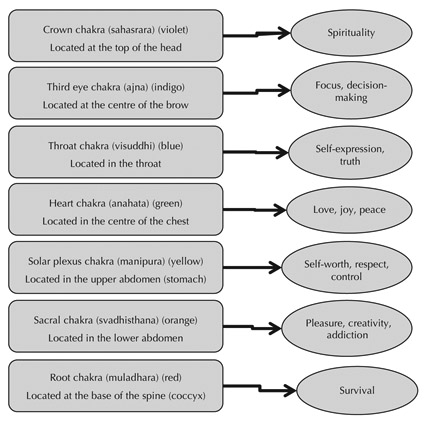

The word ‘chakra’ is derived from a Sanskrit word meaning ‘wheel’. A chakra can be thought of as an energy centre and there are seven major ones in the human body working in synchronicity and an imbalance in one will affect others. The chakras are essentially the body’s invisible power source that connects your spiritual body to your physical one. Sometimes chakras can become blocked (because of stress, emotional or physical problems) so the energy system cannot flow freely, resulting in physical illness, discomfort or a sense of being mentally and emotionally out of balance. Like Maslow’s pyramid, the chakras can be considered a hierarchy of support and control (Figure 5).

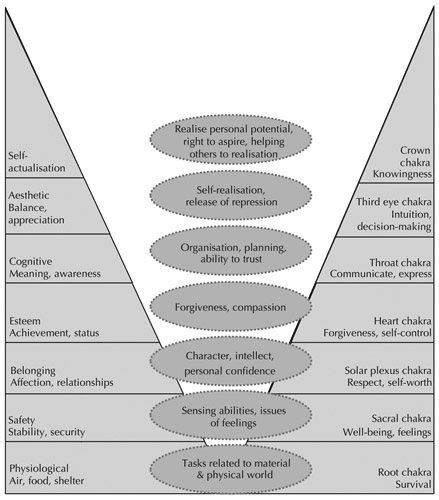

In the same way that Maslow’s pyramid demonstrates a successive order of need to be satisfied in turn, the ladder of chakras shows the chain of spiritual or emotional needs that must each be met in turn before progressing to the next. Both philosophies see personal development as the path to ‘completeness’; for the West the path is more tangible, with materialistic milestones, and for the East it is more ethereal, with emotional waypoints. So, while the two concepts appear initially to bear no relation to one another, the defining characteristics of each step demonstrate the closeness of their relationship (Figure 6).

Figure 4

The ‘chakra’ system

Welfare may be translated as ‘heart function’ as we continue to exist and need our heart to work for us. While Western thinking centres on the physical self and Eastern on the emotional, the body’s welfare exists as a permanent balancing act between our emotional, physical and psychological state. Because our emotional, physical and psychological state are all inextricably intertwined, anything that affects one will inevitably have an impact upon another; an imbalance in one element, means another must react to compensate in order to try to maintain the body’s equilibrium. The heart exerts a formidable control over the brain and thus the heart affects mental clarity, creativity, emotional balance and personal effectiveness. Elaborate circuitry enables the heart’s ‘brain’ to act independently of the cranial brain – to learn, remember and even feel and sense. By being mindful of, and ensuring, our emotional, psychological and physical welfare, we can exist in equilibrium and control our wellbeing. Thus, Western and Eastern thinking can be considered two sides of the same coin, both striving for the same goal but considering different routes.

Figure 5

The ‘chakra’ hierarchy

Whether ascribing to Western or Eastern philosophy, knowing and understanding the attributes of each stage of the elemental hierarchy, we can begin to understand our drivers (motives) and thereby begin to take control of our lives and ourselves. This understanding is often referred to as emotional competency, which focuses on two elements:

The level of possession of both competencies determines the extent to which we build supportive networks around us; a low level of emotional competency indicates a poor social capacity where people tend to become isolated, with low motivation to develop positive relationships, thus gaining little personal fulfilment. To have motivation and to

Figure 6

The relationship of needs to chakras

be motivated requires a motive, a stimulus for action (which may or may not be consciously recognised) and a decision to respond to that stimulus, leading to an action (Adair 1996). The implication of this is that to have motivation we must derive some reward, extrinsic or intrinsic, suggesting that motives (hence motivation) are attached to emotions. Physically, the mind and body are interlinked and, being parts of the same cybernetic system, have a close effect on one another. A person’s perceptions, emotions, physiological responses and behaviour all occur simultaneously and are driven by the brain, over which the heart has formidable control, so it is possible to control our emotional self through understanding and thought. The heart is far more than a simple pump, but a highly complex, self-organised information-processing centre with its own functional ‘brain’ that communicates with and influences the cranial brain via the nervous system, hormonal system and other pathways. These influences profoundly affect brain function and most of the body’s major organs, ultimately determining our quality of life. Thus, by understanding and controlling how we think, we can change our physiology, feelings or behaviour.

Adair, J. (1996) Effective Motivation. London: Pan Books.

Maslow, A. (1943) A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review 50: 370–396.