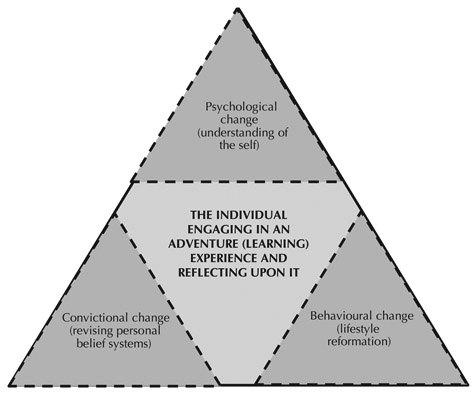

Figure 7

Reflective learning through adventure experiences

Adventure learning can be built into almost any sphere of developmental work. Many workers engaged with youth justice programmes, youth work and ‘alternative’ curricula have taken the activity-based approach, seeing adventure learning as a route to individuals growing healthier emotionally, socially and spiritually through ‘informal learning’. The emphasis is almost entirely on challenge and perceived risk, adrenalin experiences followed by supported transformative reflection, whereby learners reevaluate their previously held beliefs that were based on assumptions derived from and understood through others and through past experiences. There is a school of thought that the outdoor experience should be left as an untainted entity, allowing participants to process the engagement and derive their own unique conclusions from it with little or no external interference from the instructor, other than to support reflection. The learning is assumed to happen naturally, with the individual at the centre of a triangle of life-affirming processes (Figure 7).

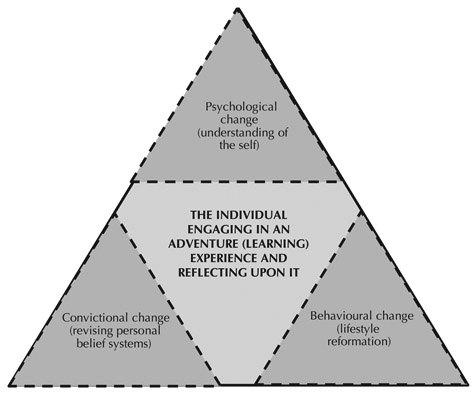

This triangular model is two-dimensional, assuming the learner has an innate biological capacity for self-reflection and avoids the extended outcome of taking a more holistic approach to learning, ignoring the possibility and the opportunity to use adventure (the outdoors) as a tool, a ‘means to an end’. Children and young people have no choice but to spend a significant proportion of their time in formal learning (about 13% of their life between the ages of 5 and 18 years) because they are legally obliged to be in school. The subjects to be taught are pre-determined through the curriculum and, because they are effectively factories of knowledge, schools have to be efficient, focused in the delivery of that curriculum. This means that structures and systems have to be established so that the teacher can deliver to the mass of pupils and the pupils can gain some knowledge; there is an integral supposition that inevitably most pupils will learn something, although they probably cannot achieve their potential. Increasingly this process means that each step of the way is monitored and the learning product measured; that is, a volume approach with directly proportional reliance upon rote learning and examination regurgitation. This system takes the simplistic approach of segregating each

Figure 7

Reflective learning through adventure experiences

subject and teaching it as an isolated entity, with no correlation to another subject or connecting the subject learning into the reality of life (the silo method), in other words school learning does not take a holistic approach. Within the modern world, it is time for schools to move away from this blinkered approach and look to developing more inventive ways to teach children and young people. Life does not exist as a series of unique silos, but as a web of integrated and interacting entities, so children and young people should not be taught to manage it that way. Embedding adventure learning into a (school) curriculum involves curricular, cross-curricular and extra-curricular learning; in other words, adventure learning is holistic, not only teaching a topic in itself, but linking it with other subjects and developing knowledge and understanding beyond that which may lie in the curriculum. The logic behind embedding adventure is the core recognition that people learn in different ways and that when planned as carefully as indoor learning, outdoor learning has equal value to indoor learning. Learning outside the classroom capitalises on and develops different learning styles; experiencing something, as opposed to hearing or reading about it, helps to improve children’s and young people’s recall and reflective skills, as they can relive the event in their heads. Adventure learning is enhanced by the environment within which it occurs, by the range of adaptable natural resources; fostering the integration of indoor and outdoor experiences brings the educator, be that a teacher or outdoor professional, to consider the experience rather than the use of resources, which allows children and young people to be in control of their own learning.

Ofsted, the United Kingdom’s inspection and regulatory body for care, education and skills, views adventure learning as critical to the delivery of a broad and balanced curriculum. School inspections consider the quality and extent of outdoor learning opportunities, whether they are continuous and progressive, their impact on learners, whether they link experience and learning inside and outside the classroom. The clear conclusion from inspection reports is that the greater the level of planning and integration of adventure and classroom learning, the higher the quality and the better the outcomes for learners.

There is an old adage called ‘the six Ps’: prior preparation and planning prevents poor performance. All that it takes for a lesson to move from a passive, indistinguishable endurance, to an active, memorable engagement, is planning. All teachers have to do lesson plans, adventure learning simply entails looking to take the learning in a new direction; teachers can team up to plan cross-curricular lessons and so share the burden of innovation. The result is a multi-dimensional, multi-layered programme to address curriculum topics, social education and personal development. The process of reflection and change need not be a protracted, separate component, but an integral element of the activity: a positive remark, a personal perspective, a non-judgmental comment. The reflective process should appear in the activity as unobtrusively as possible, and as a natural part of the overall experience, not a contrived interruption that breaks the flow.

The same approach applies to the off-site experiences that so many schools offer. It seems to have become accepted that schools will offer annual residential experiences at professional outdoor centres, in order to offer a more ‘meaningful’ outdoor experience. The increasing focus on the technical and safety aspects of experiences seems to have brought about a fear of taking the classroom outside and a belief that expensive opportunities for the few make the experience more powerful and safer. However, too often, these experiences are limited, even marred, by the activity being the focus, with instructors concerned with whether the participant can hold the paddle correctly, tie the figure of eight or understand the compass; the ‘supported reflection’ then becomes a final, wind-down ‘add-on’ at the end of the session. When responsibility for the adventure learning session is delegated outside the learning organisation, when it is handed to a professional organisation with a menu of pre-determined activities, teachers can see it as a break from their normal routine and disengage from it. Communication and planning between school staff and instructors would allow a diverse and multi-dimensional programme to deliver a range of subject learning and development opportunities. However, it has to be questioned whether occasional ‘big’ experiences maximise their potential; many schools seem to have lost sight of the fact that the more meaningful experiences of learning take the outdoors as a natural tool and that lessons can be built into the school grounds, local parks or other open spaces.

The perception of adventure learning is often restricted to an aspect of physical education, with perhaps a bit of social education and personal development attached. Physical education is wedded to adventure learning through the process of actively engaging in an activity, but there the similarity ends; it is an integral part of the school curriculum, but within the silo method is designed towards team sport and competition. Nationally there is recognition that young women particularly are unlikely to continue with physical activity into adulthood, which can have serious and damaging health and lifestyle consequences as they get older. Not only does regular activity improve physical and mental health, but also women play a strong influencing role within their own families and are more likely to be a positive role model to their children than highly publicised sporting events or media profiles. Not restricting the curriculum to traditional methodologies and by using physical activity as a consequence rather than the focus, participants develop a different perception and forget they are ‘exercising’.

The National Curriculum of the United Kingdom recognises that different outdoor learning experiences offer additional opportunities for personal and learning skills development in other areas such as communication, problem solving, information technology, working with others and thinking skills. The National Curriculum was introduced into England, Wales and Northern Ireland as a nationwide mandatory programme of teaching for primary and secondary state schools following the Education Reform Act 1988. Its purpose was to standardise the teaching programme in order to enable assessment and thus the compilation of league tables. However, the National Curriculum applies to state schools only, independent and private schools may set their own curriculum and while academy schools are state funded, they are granted significant autonomy in deviating from the National Curriculum. As increasing numbers of schools move away from state to academy status, they become increasingly liberated to develop innovative and laterally conceived frameworks of learning. Learning in the outdoors can make significant contributions to literacy, numeracy, health and wellbeing. In literacy, there are opportunities to use different texts: the spoken word, charts, maps, timetables and instructions. In numeracy, there are opportunities to measure angles and calculate bearings and journey times. In health and well-being, there are opportunities to become physically active in alternative ways and to improve emotional wellbeing and mental health. Therefore, adventure learning offers many opportunities for learners to deepen and contextualise their understanding within curriculum areas, and for linking learning across the curriculum in different contexts and at all levels. A large volume of evidence has built up that clearly demonstrates the benefits for children and young people of acquiring their learning and personal development outside the classroom; this can be summarised as:

Providing a progressive range of sustainable adventure learning experiences may mean maximising the use of the local area, making repeat visits at different levels to add depth to the experiences, building on and enhancing the learning. From a learner’s point of view, each visit, including ones to the same place, will offer a different perspective, enriching the curriculum and providing greater coherence. Effective planning can make the same activity in the same location a completely new and meaningful experience, seamlessly entwining progressive adventure learning with indoor learning. As an embedded part of the holistic (overall) learning experience, the learning begins to happen naturally. The school grounds are generally the first, natural and non-threatening step in taking learning outside. This offers a means of building confidence for teachers and helps to avoid issues of consent and allay safety concerns. The learning context will be changed with the variable context of the group, for example, a rural school may be well acquainted with their ‘green’ surroundings and adventure learning may be predicated on an urban environment, whereas an inner city school may head to the countryside. While breadth and depth of learning should not be linked to distance from the establishment, environment can be a powerful tool. Learning and meaning in adventure learning occur through ‘real life’, ‘hands-on’ activities, which is the combination of what, how and where we learn.