Q. You don't call a Chinaman or an Italian a white man? No, sir; an Italian is a Dago.

—Testimony of construction superintendent in Congressional hearings (1890)

The thefts and pocket pickings now pale into insignificance when compared to the achievements of the racketeers…the rackets in connection with liquor, dope, food, milk, the building trades…the use of gangsters in labor troubles.

—Testimony of criminologist in Congressional hearings (1934)

In the 1950s, Giovanni “Johnny Dio” Dioguardi was a national expert on the art of labor racketeering. He had come a long way from his childhood in Little Italy.1 When he was twenty years old in 1934, Dioguardi represented the Allied Truckmen's Mutual Association in a dispute with Local 816 of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters.2 A labor mercenary, Dioguardi later created “paper locals” of the Teamsters for his ally Jimmy Hoffa. Dioguardi forged himself into a “labor consultant” by applying select mayhem at weak points in a union.3

But Johnny Dio had also been riding a wave of social forces for decades. He came of age as the labor movement was taking off in the 1930s, and he dealt with unions comprised of southern Italian immigrants. This chapter reveals why and how the Cosa Nostra captured so many union locals in Gotham. Demographics and the labor movement converged in the 1930s to fuel the Mafia's takeover of unions.

“ETHNIC SUCCESSION IN CRIME”: AN INCOMPLETE EXPLANATION FOR ORGANIZED CRIME

In 1960, the sociologist Daniel Bell argued that organized crime was one of the “ladders of social mobility in America” for new immigrant groups.4 Building on Bell's idea, Francis Ianni argued in his 1974 book Black Mafia: Ethnic Succession in Organized Crime that there was a process of “ethnic succession” in crime: as immigrant groups assimilated they were replaced by newer groups. As Ianni put it, “the Irish were succeeded in organized crime by the Jews…Italians came next…[and] they are being replaced by…blacks.”5

Later writers have pointed out that the ethnic succession model is too one-dimensional. Immigrant groups were treated differently, and their respective crime syndicates emerged at different times.6 Therefore, to understand why the Mafia became the dominant labor racketeers during the New Deal, we need to compare the Irish, Black, Jewish, and Italian gangsters against the backdrop of New York history.

THE EARLY GANGSTERS: WHY THE IRISH RACKETEERS GRADUALLY DISAPPEARED

The Irish immigrated first and assimilated earlier. The Irish Potato Famine of 1845–1852 caused hundreds of thousands of Irish to leave for New York by the Civil War. In Gotham, they endured anti-Irish and anti-Catholic bigotry, urban squalor, and poverty.7

By the end of the century though, the Irish were assimilating rapidly. Irish politicians were elected mayor in 1881 and 1893, and Irish voters were filling government patronage jobs.8 By 1930, an astounding 52 percent of the City of New York's public-sector employees were Irish. As historian Jay Dolan put it, “Where once the refrain was ‘No Irish need apply,’ it now may as well have been ‘Only Irish need apply’!”9 Meanwhile, about 21 percent of New York's Irish were married to a non-Irish spouse, a rate three times higher than Jews and southern Italians.10

The Irish underworld was affected by these social forces. The assimilation of Irish immigrants reduced Irish laborers in racketeer-prone industries. “We want somebody to do the dirty work; the Irish are not doing it any longer,” said a police official bluntly in 1895. “We can't get along without the Italians.”11 As Irish enclaves disappeared, so too did the Irish street gangs. When the Five Points slum was Irish, it was the home territory for Irish gangs like the Roche Guard. By the 1890s the Five Points was Italian and the Irish gangs were gone. The Hudson Dusters and the Gopher Gang were confined to the Irish West Side of Manhattan.12

The Irish gangsters of South Brooklyn had a sorry ending. On December 26, 1925, Richard “Pegleg” Lonergan and five men of his White Hand gang got drunk and had a bad idea. They took taxicabs over to the Adonis Social Club, an Italian mob hangout in Brooklyn. Staggering into the hall, one boasted that his brother could “lick the whole bunch single-handed.” Unfortunately, Al Capone was sitting in the club, fresh from Chicago, where he had been fighting Irish bootleggers. A hail of bullets killed “Pegleg” Lonergan and two compatriots.13

While Prohibition temporarily boosted the Irish bootleggers, the Irish mob as a whole continued to decline. Joe Valachi started out with an Irish gang before joining the Mafia. The Irish assassin Vincent “Mad Dog” Coll ended up working for Salvatore Maranzano. Madden left for Hot Springs, Arkansas in 1935.14 Had Irish immigration peaked forty years later, organized crime may have been quite different. We might today be discussing the Dwyer, Higgins, Lonergan, Madden, and McGrath gangs of the Irish mob.

THE RACE FACTOR: WHY AFRICAN-AMERICAN AND CHINESE RACKETEERS WERE ISOLATED

Though African-American gangsters were strong in black Harlem and San Juan Hill, there were no major black labor racketeers in New York City. This was not for lack of interest. In 1935, a former FBI agent reported that Casper Holstein, Harlem's “Bolito King” (a numbers lottery), was backing union violence in his native Virgin Islands.15 Although Chinese tongs engaged in forms of racketeering in Chinatown, they were nonentities in Gotham's unions.16 This was due in part to their smaller numbers, but it was also the result of prejudice in the underworld.

African-American and Chinese racketeers had relatively few entry points to union hierarchies. The building trades were notorious for preserving the Irish and Italian dominance of the construction industry at the expense of black workers. The International Longshoremen's Association did not have a single black union organizer on staff into the 1950s. It is inconceivable that any African-American longshoreman with criminal ties could have risen to be a union pier boss in the way that Anthony Anastasio did.17

Racial distrust ran through the underworld, too. As we will see, the Corsican drug traffickers refused to work with African Americans. The black gangster Frank Lucas recalls how even after he became friends with Vincent “The Chin” Gigante in prison, they “never talked business,” since they “wouldn't have had anything to talk about in that sense.”18

SOMETIME RIVALS AND FREQUENT COLLABORATORS: THE JEWISH RACKETEERS

Only the Jewish syndicates were roughly on par with the Cosa Nostra as of the 1930s. The Jewish gangsters have been portrayed as hired help for the Mafia. They were more than that. Jewish and Italian gangsters regularly met on equal footing and pulled off schemes together. Some like Meyer Lansky and Moe Dalitz worked alongside wiseguys well into the 1960s.19

Overall though, the Jewish crime syndicates were being surpassed by the Mafia starting roughly in the mid-1930s. Why did the Jewish labor racketeers decline?

Large-scale Jewish immigration began somewhat earlier than south Italian immigration, and Jews exited racketeer-prone industries somewhat earlier.20 Driven out by pogroms from urbanized, artisanal communities in Eastern Europe, 64 percent of Jewish immigrants were artisans or skilled workers. By comparison, south Italian immigrants, who came largely from underdeveloped rural areas, were about 25 percent artisans and skilled workers.21 The children of Jewish immigrants were far more likely to become business managers, sole proprietors, or professionals. Jews went to college at higher rates than any other group, especially after the Second World War. By 1950, 75 percent of second-generation Jews were white-collar workers, compared to 33 percent of second-generation Italians.22

Potential sources of new Jewish gangsters were disappearing as well. In the 1940s and ’50s, Jews flocked to the suburbs in huge numbers, causing inner-city enclaves to recede. Brownsville, Brooklyn, was once the home base of Jewish gangsters.23 By the time Henry Hill was growing up in Brownsville in the 1950s, he was drawn to Paul Vario's crew of the Lucchese Family.24 The Jewish gangs also appear to be less kinship-based than the Mafia “families.” Although there are dozens of books by ex-mobsters who followed relatives into the Mafia (for example, Michael Franzese's Blood Covenant),25 there are virtually no equivalent memoirs by Jewish criminals who followed family into the mob. As historian Jenna Weissman Joselit puts it, organized crime “was a one-generation phenomenon” for Jews in New York.26

MOB ON THE ASCENT: THE ITALIAN-AMERICAN MAFIA

The Italian-American Mafia was best positioned to take advantage of the growth of labor unions in the 1930s. The reasons for this lay in patterns of immigration and labor force participation.

South Italians in the Labor Force: An “Inbetween People”

The early Sicilian immigrants, with their dark skin and unfamiliar customs, were deemed not fully “white” in the eyes of many native-born Americans. As the scholar Robert Orsi has shown, south Italians were treated like an “inbetween people,” who were “neither securely white nor nonwhite.”27 When a construction superintendent was asked about Italian laborers at a Congressional hearing in 1892, he gave this revealing answer:

Q. You don't call a Chinaman or an Italian a white man?

A. No, sir; an Italian is a Dago.28

Those from the Mezzogiorno, the economically underdeveloped south of Italy, were largely agricultural or unskilled laborers, and came under the padrone system of contract labor.

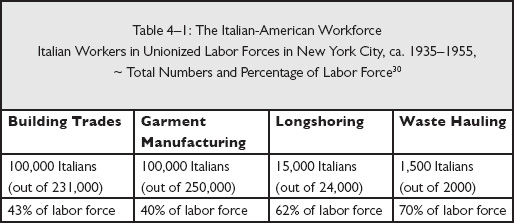

As a result, Sicilians and other south Italians were relegated to the toughest, dirtiest jobs. As a 1931 study found, “The Italian has perhaps been the most generally abused of all the foreign born” and thus Italians “have done the hard and dangerous work in the community.”29 This is reflected in the labor force. Italians worked disproportionately in Gotham's most labor-intensive industries. They represented 40 percent or more of the building trades and the garment manufacturing, longshoring, and waste hauling industries (see table 4–1).

South Italians were a significant portion of the seventy thousand teamsters so critical to moving goods through the city. Most of the ten thousand independent ice and coal dealers were from southern Italy. About 90 percent of the thirteen hundred licensed pushcart peddlers of fruits and vegetables were Italians. Fully one-third of the eighteen thousand members of New York's largest musicians’ union were Italians who, along with African Americans and Jews, were essential to the nightclub business.31 These were all “fragile” sectors prone to extortion or racketeering.

Why the Mafia was Poised for Labor Racketeering

Driven into the most labor-intensive jobs, Italian workers ironically came to dominate key labor forces by the 1930s (see table 4–1). The Little Italies were still thriving enclaves, skeptical of police, the home base of mafiosi, and the recruiting grounds for young men. At the same time, second-generation Italian Americans were increasingly accepted as “white” by society. “The Chinese who seeks to leave his Chinatown is under a severe handicap not experienced by the Italian who emerges from Little Italy,” observed a sociologist in 1931.32 During the New Deal, Italian American workers became strong constituencies, courted by labor leaders, and in control of many union locals.33

These forces positioned the Mafia families for labor racketeering. Racketeers preyed on industries and unions that were most accessible to them. As historian Jenna Weissman Joselit explained, early Jewish racketeers took advantage of “the kosher poultry and garment industries while the Italians followed suit by exploiting their countrymen in the fish, fruit, and vegetable markets.”34 The modern Mafia likewise thrived in industries that were heavily southern Italian.35

What explains this connection? There are multiple reasons:

First, union locals comprised of Italian workers demanded to be represented by Italian labor leaders. This limited rival Irish and Jewish racketeers. The Irish presidents of the ILA ceded the Brooklyn locals to Italian mobsters for this very reason. “[President] Teddy [Gleason] is still Irish. You understand? He joined forces because he got no choice,” said racketeer Sonny Montella on a surveillance bug.36 In the construction industry, while Irish leaders held on to the highest skilled building trades, there were union locals made up entirely of Italians, some of which came under the influence of mafiosi.37

Second, Italian mafiosi could call on neighborhood and kinship ties in Italian labor forces—“networking” in today's parlance. ILA official Emil Camarda had known Mafia boss Vincent Mangano from growing up together in Sicily. One of his successors, ILA Local 1814 official Anthony Scotto, had as an in-law Albert Anastasia. When the boxer Rocky Graziano was turning professional, connected guys in the neighborhood introduced him to Eddie Coco, a mob associate, and told the young fighter that Coco would be his new manager.38

Third, Italian mobsters could conversely apply social pressures to roll over dissidents. When John Montesano, the owner of a family waste-hauling business, wanted to get out of a partnership with a mobbed-up carter, the Mafia demanded he pay a gratuitous $5,000 fee. Montesano was pressured into paying by a blood relative who also happened to be a member of the mob. “What is wrong with you, kid? Every time I turn around, you are in trouble,” his relative warned.39 Similarly, it was extremely difficult to reform the Brooklyn waterfront when so many ILA thugs and convicts lived amongst the longshoremen.

Fourth, as Italian workers became business owners in these industries, it facilitated collusive behavior between business and labor. Since the waste-hauling industry was made up of Italian families who knew each other, it was easy to form cartels to exclude outsiders.40 Likewise, as Italian construction workers became material men and suppliers, Mafia-run cartels flourished. Sammy “The Bull” Gravano, an ex-construction worker, transitioned easily into the building rackets as a rising member of the Gambino Family.41

THE MAFIA'S TAKEOVER OF UNION LOCALS IN THE 1930s

The Mafia families used these entry points to emerge as the top labor racketeers in industry after industry. As we saw earlier, Italian gangsters like Paolo Vaccarelli and the Anastasio brothers took over ILA locals as the workforces changed from Irish to Italian. By the 1930s, the Cosa Nostra controlled ILA locals in South Brooklyn, Staten Island, and key Manhattan piers.

New York's construction industry saw a similar evolution. During the 1920s, the Lockwood Committee investigation uncovered “tribute” payoffs to building trades czar Robert Brindell, and business cartels engineered by the building contractors. Out of the more than five hundred defendants who were prosecuted, none of the labor officials, and only a small set of building contractors, were Italians. Starting in the late 1950s, scores of mafiosi, mob-linked labor officials, and contractors were being prosecuted or investigated for similar rackets.42

In Lower Manhattan's garment industry, the Mafia entered the industry after Italian workers opened their own garment shops. The Cosa Nostra was very conscious of the new opportunities this presented. “It used be that that this industry was all Jewish, but now the Italians are really getting into it,” John Dioguardi explained to other mobsters. “Guys like Joe Stretch [Joe Stracci] control big companies like Zimmet and Stracci.” The Mafia focused on trucking union locals in the garment district, and on diverting production to nonunion shops.43

In the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, President Daniel Tobin had once dismissed Italian immigrants as “rubbish.”44 As these new immigrants became truckers, the IBT organized them. Later on, Tobin began receiving death threats from mobsters seeking to “break into our local unions.” Mafiosi Vito Genovese and Joseph “Socks” Lanza defeated a campaign to reform IBT Local 202 by branding their opponents as Communists and making nationalist appeals to Italian teamsters. Jimmy Hoffa cut deals with Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo and John Dioguardi.45 IBT official Roy Williams dealt with Italian, Jewish, and some Irish mobsters because that was “the way New York is separated out anyway.”46

THE NEW DEAL: THE SURGE OF LABOR UNIONS IN THE 1930s

The Mafia's racketeers came to power just as the labor unions were taking off in the 1930s. Simply put, the Cosa Nostra had great timing.

After a long history of employer attacks on unions, New Deal–era legislation granted unprecedented rights and protections to labor unions.47 Labor union membership surged. In 1908, New York City had 240,000 union members. By 1950, union membership quadrupled to a million—upwards of one-third of Gotham's workforce.48

Although legitimate unionists were the main beneficiaries, the Mafia took advantage of the shift toward labor as well. In the first year of operation of the government's new Regional Labor Boards (1933–34), complaints and arbitration demands against employers were filed by none other than: Building Service Employees Local 51B, represented by George Scalise, a partner of mafioso Anthony Carfano;49 IBT Local 202, a mob-controlled trucking local in the fresh-food markets, which would see its union officials go to prison for racketeering;50 and Teamsters Local 138, which was controlled by Jewish racketeer Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, who used the union and a trucking association to extort payoffs in the baking industry.51

Many union locals ended up sheltering racketeers from scrutiny, too. With notable exceptions, like those of David Dubinsky of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and Walter Reuther of the United Automobile Workers (UAW), national unions avoided dealing with racketeers in union locals. Reform was stymied by a hands-off approach to locals, mobster intimidation, and the weakness or indifference of rank-and-file members. Meanwhile, J. Edgar Hoover's FBI was lackluster in pursuing cases of union corruption.52

THE MOB'S UNION LEVER

The labor union became a new lever of power for the Mafia. Not only was labor racketeering a moneymaker for the Mafia families, but it also gave them influence over businessmen and politicians in New York and the United States. “We got our money from gambling, but our real power, our real strength, came from the unions,” said mobster Vincent “Fish” Cafaro. “Ultimately, it was labor racketeering that made Cosa Nostra part of the sociopolitical power structure of twentieth-century America,” James Jacobs argues convincingly.53

Greater coordination between the Mafia syndicates, the expansion of national labor unions, and the advent of telephones and airplanes all facilitated labor racketeering across the country. “The gangsters who infiltrated a local in New York were tied into a national syndicate that included gangsters attempting to do the same thing in Chicago, Kansas City, and in numerous other locations where Teamster locals and criminal organizations existed side by side,” described a report on the IBT.54 In dealing with the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), Chicago Outfit leader Paul Ricca told mobsters “to be free to call on Charlie Lucky [Luciano] or on Frank Costello…if we find any difficulties here [in New York] in our work, and if we need anything to call on them, because that is their people.”55

Take John Dioguardi's consulting work on the ILGWU. In 1953, Dioguardi flew to California to assist mobsters in entering the garment industry in Los Angeles. He told them to target an ILGWU official. “What you've got to do is hurt this fucking guy and make him run to New York,” Dubinsky advised. “Let [David] Dubinsky know you're going to have your own fucking way out here.” They sent a union official to the hospital with a cracked skull, and opened a union-free shop. The kid bully from Little Italy had gone national.56

CASE STUDIES OF MOB POWER OVER NEW YORK UNIONS

Equally important as taking power was keeping and using that power. The following case studies show how the Mafia controlled and exploited unions.

Case One: Squashing Union Reformers—The International Longshoremen's Association on the South Brooklyn Docks

The Mafia used fear and terror to maintain its stranglehold on the South Brooklyn waterfront. In 1939, an insurgent led a rank-and-file uprising of longshoremen. The mob's reaction taught a terrible lesson to anyone who would challenge its power.

The Mob's Waterfront in the 1930s

No outsider could crack the waterfront. Organizers for the Communist Party USA in Manhattan got nowhere on the other side of the East River. CPUSA organizers spread leaflets attacking the ILA in Brooklyn, but they gained little traction among the Catholic longshoremen.57

Although the prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey obtained convictions of racketeers in the restaurant and garment business, and sent Charles Luciano to prison in 1936 for a prostitution ring, he got nowhere on the waterfront. Later in life, Dewey revealed what happened. “There was a time when we thought we had it organized…to really make frontal assault on the waterfront,” he recalled. “We finally found a policeman who would undertake to be head of the undercover investigation.” The officer had second thoughts. “After a week of it, he came back and said, ‘I'm sorry. I'd like to ask to be excused from this assignment,’” recounted Dewey.

The prosecutor described the web of power on the docks. “The unions were filled with ex-convicts,” he noted. “They don't talk.” The shippers were often complicit in schemes to ensure labor peace. “You can never tell whether what you've found is extortion or bribery,” explained Dewey. Most importantly, the “political power of some people connected with the water front is very great, and they've always been close to Tammany Hall.” The racket buster was stymied on the docks.58

The Insurgent: Peter Panto and the 1939 Campaign

Peter Panto was an unlikely insurgent. Born in America in 1911, he spent his childhood in Italy and returned to Brooklyn as a young man. Like so many poor Italians, Panto became a longshoreman on the Red Hook piers. As a member of ILA Local 929, Panto paid union dues to Anthony Giustra (brother of the slain gangster Johnny “Silk Stockings” Giustra).59

Panto was stirred by the indignities he suffered under his own union. Panto gave back almost half his salary through kickbacks to get work. What really bothered him was that the ILA sold eight thousand mandatory “tickets” to a Christopher Columbus Day Ball in a hall that held only five hundred. For all that, the ILA did not even hold rank-and-file meetings.60

In the spring of 1939, the twenty-eight-year-old Panto began organizing private meetings with fellow longshoremen. Panto had an infectious smile, he spoke both Italian and English, and he was persuasive in both. He started calling public meetings in Brooklyn. The audience grew from several hundred to over twelve hundred longshoremen by July. In Panto's speeches, he raised practical issues like: “Are you in favor of Union Hiring Halls?” or “Are you ready…to help organize the I.L.A. on a democratic basis?”61 To the mob, those were dangerous ideas.

Albert the Executioner

A gangster took Panto aside one night. “Benedetto [blessings],” the gangster said menacingly as he sliced his finger across his neck.62 Panto was undaunted. On Wednesday, July 12, 1939, Emil Camarda, union boss of the Brooklyn ILA locals, summoned Panto to his office. When he arrived, a bunch of goons were standing around Camarda. “Peter, some of the boys don't like the way you're calling meetings and making a rumpus,” Camarda told him. “Some of them might want to harm you, but I told them you're a good fellow.” Panto refused to stop.63

Albert Anastasia had had enough of this troublemaker. Nothing was getting through to this guy. Anastasia talked to his henchmen about “some guy Albert had a lot of trouble with down in the waterfront,” who was “threatening to expose the whole thing.” Albert the Executioner came up with a solution.64

On Friday, July 14, 1939, Panto was shaving for a night out with his fiancée. A call was placed to Panto at the store across from his boardinghouse in Red Hook. The caller persuaded him to come to a meeting. “I don't think it is entirely on the square,” he told his fiancée. Nevertheless, he kissed her goodbye, put on his fedora, and walked out the door. Panto was last seen entering the automobile of an ILA official with two men, one of whom was later identified as Anthony Romero.65

Peter Panto looked out the window at Manhattan as the car crossed over to New Jersey. When they arrived, Panto walked into the house for the meeting. Waiting inside were James “Jimmy” Ferraco, Emanuel “Mendy” Weiss…and Albert Anastasia. As soon as Panto walked in he realized what was happening. Panto lunged for the door. Mendy Weiss, a hulking thug, grabbed him and “mugged him.” Panto bit and scratched Weiss's huge hands, desperately trying to break his grasp. We can only imagine the terror running through the young longshoreman's mind in those final moments.66

The men transported his dead body to the marshy meadowlands outside Lyndhurst, New Jersey. They dumped him in a shallow grave and covered him in quicklime.67 Whenever the Mafia is romanticized as the “Honorable Society,” or minimized as a supplier of victimless vice, Peter Panto's last night on earth should be remembered.

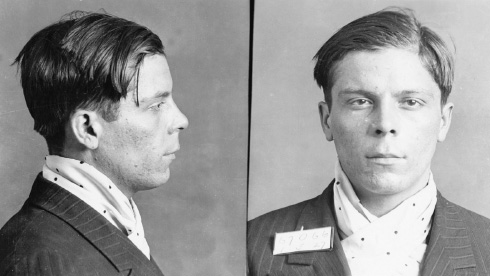

4–1: Official photograph of Peter Panto distributed by NYPD in 1939. (Courtesy of the New York Police Department)

Terrorizing the Rank-and-File Committee

After Panto disappeared, graffiti started appearing on pier facilities: “Where is Pete Panto?” It became a rallying cry. That October, Pete Mazzie, a twenty-three-year-old longshoreman, called for a public meeting of the Rank-and-File Committee. About four hundred longshoremen filled the chairs of the smoke-filled hall. A gang of thugs took seats smack in the middle of the hall.

“This is the opening of a headquarters where longshoremen can meet and talk,” Mazzie declared. “The rank-and-file committee is taking up where Pete Panto left off. So any phonies present tonight will find—”

“What do you mean by phonies?” shouted a tall thug popping up from his chair.

“I'll tell you what I mean—” Mazzie tried to continue.

The thug stormed up to the speaker's table and slugged Mazzie. Another goon bashed a chair over Mazzie's head. By the time the police arrived, the hall was a wreck and Mazzie was on his way to the emergency room.68

4–2: Albert Anastasia, October 1936. (Courtesy of the New York Police Department)

Even as he was recovering, Mazzie was warned that he “better watch his step, and remember what happened to Pete Panto.”69 In January 1941, investigators dug up Panto's body in New Jersey. His corpse was so badly decomposed that he had to be identified by his teeth. Brooklyn District Attorney William O'Dwyer's office publicly identified the suspects as Anastasia, Ferraco, and Weiss. O'Dwyer later claimed the case fell apart on November 12, 1941, when one of the key witnesses, Abe “Kid Twist” Reles fell—or was thrown—out of the sixth-floor window of the Half Moon Hotel while under police custody. Few longshoremen believed Reles fell on his own. The violence had an effect. Panto became a martyr on the docks. But fewer and fewer longshoremen dared appear at public meetings. The uprising fell apart.70

CASE TWO: RUNNING A UNION RACKET QUIETLY—UNITED SEAFOOD WORKERS LOCAL 359

Although the Mafia demonstrated it was capable of extreme violence, most of the time it sought to manage its labor rackets quietly. When possible, the Cosa Nostra preferred more subtle forms of coercion, and collaboration with corrupt businessmen. This was revealed in the 1935 federal prosecution under the Sherman Antitrust Act of Joseph “Socks” Lanza of the United Seafood Workers Local 359.71

The Mob in the Fresh Fish Markets

Fresh fish rots quickly. This biological fact gave the fish handlers leverage beyond their rank in life. The teenage Joseph “Socks” Lanza realized this soon after he started working in the Fulton Fish Market in the 1910s. In 1923, when he was barely twenty, the precocious Lanza helped organize Local 359 of the United Seafood Workers union. Lanza's cronies founded the Fulton Market Watchmen and Patrol Association to collect a “protection fund” from retailers to prevent thefts or “labor troubles” in handling their perishable fish.72

The first investigations into the fish markets focused not on the Mafia, but on Jewish fish wholesalers. In July 1925, the federal government charged seventeen fish wholesalers for conspiring to violate the Sherman Antitrust Act by “creating an artificial market and dictating prices to retailers.” They pled guilty and paid fines.73 Then, in September 1926, the state attorney general charged fish companies with another conspiracy to “restrain competition, increase prices and conduct a monopoly in white fish, carp, pike and other fished used by Jewish people during the forthcoming holidays.” But witnesses failed to cooperate.74

June 1935, United States v. Joseph Lanza, et al., Federal Courthouse, Manhattan

In United States v. Joseph Lanza, et. al., the United States Attorney charged eighty individuals and corporations with conspiring to monopolize the freshwater fish industry in New York City in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Joseph “Socks” Lanza and his United Seafood Workers local were accused of conspiring with several crooked businessmen. The defendants included twenty-five corporations with respectable names like the Delta Fish Company, Inc., the Geiger Products Corporation, and the Lay Fish Company.75

The June 1935 trial did not involve any accounts of homicide or even physical assaults. Rather, the witness testimony revealed how the conspirators cleverly used a trade association and business coercion, along with the labor union and subtle threats, to obtain control of the fish markets. Lanza lurked in the background, only occasionally revealing himself.

The Trade Association and Business Coercion

The aim of the conspiracy was to control the supply of fresh fish going into New York City to thereby artificially fix prices. To accomplish this, several retail fish dealers organized into a citywide trade association. The trial testimony showed that the retail dealers combined “into what became known as the Bronx, Upper Manhattan, and Brooklyn Fish Dealers Association, with one of the defendants [Jerome] Kiselik, acting as the so-called impartial chairman.”76

To extend their control, Kiselik and a wholesale organizer named O'Keefe set up a meeting of the fish wholesalers at the Half Moon Hotel in Coney Island, Brooklyn “to organize to remedy the market conditions in concert with retailers.” Joe Lanza sat with Kiselik at a table on the dais, but he did not speak during the meeting.77

The businessmen defendants formed a committee to “work out a satisfactory plan for the division of profits on a percentage basis” and to “collect information as to supply, prices…and the elimination of duplication” in the fresh-fish market of New York City. Although it sounded benign, as the court properly found, the scheme “was really one to monopolize the business” of the fish market in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. And it was done by businessmen.78

United Seafood Workers Local 359 and Subtle Threats

The fish cartel probably could not have been maintained without Joseph “Socks” Lanza and the United Seafood Workers union. As shown in detail later, cartels are intrinsically unstable, and usually require some mechanism to police the cartel. In this case, it was Joe Lanza and the United Seafood Workers union. Given that almost all the hand truckmen in the fish markets in Gotham belonged to this union, it was a powerful stick in the hands of racketeers.79

The Seafood Workers union was integral to policing the cartel and controlling the supply of fish. When a new retailer brought in fish he bought from outside of New York, he would be educated on the cartel's rules. Kiselik would come by to “straighten this thing out” and instruct the retailer that he “should buy fish in New York.” Lanza would drop in on the conversation but say nothing. The union boss's mere presence was sufficient.80

For wayward retailers, Lanza engineered union problems to bring them into line. When a veteran retailer brought in fish from Philadelphia, Kiselik came by demanding to know why the retailer dared to purchase sweet-water fish in Philadelphia. The retailer replied simply that “it was cheaper.” A few minutes later, fish handlers returned and took the Philadelphia fish off his truck.81 When Booth Fisheries, one of the largest fish dealers balked at some of the association's fees, Kiselik and Lanza together paid a visit to some of Booth's intermediaries. With Lanza standing nearby, Kiselik told the intermediaries that Booth Fisheries “was not behaving in a cooperative fashion” and that he hoped “the matter might be straightened out.” Booth ended up paying the agreed fees and, in exchange, was allotted 12.5 percent of the fresh-fish market in New York—a blatantly illegal allocation of the market.82

For Joe Lanza's “services,” fish dealers funneled strange fees and payoffs to him as well. At trial, a fish retailer testified about what happened when he opened a new place of business in the market. The retailer was visited by Kiselik of the fish retailers’ association. Kiselik asked the new retailer to “see his friend Joe Socks” and pay him $500 (about $8,000 in 2013 dollars). The only reason Kiselik gave for the payment was that “Joe Socks needs the money.” During an intimidating follow-up conversation with the retailer, Lanza stood silent a couple steps away. Joe Socks got his money. But he was convicted in June 1935 and sent to federal prison.83

Case Three: Evading a Union—Keeping Out the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union

The Cosa Nostra's relationship to labor unions was purely opportunistic. When the Cosa Nostra could not gain control over a labor union, it often sought to end-run the union altogether. This is shown by the mob's attempts to keep out the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) from certain garment shops. It led to tragic results in 1949.

The Mafia and the Garment Industry

The garment industry's labor force was originally Jewish, and so were its gangsters. Benjamin “Dopey Benny” Fein was hired as a “labor slugger” for the United Hebrew Trades union to do battle with shtarkes (strongarm men) hired by employers to break strikes. In 1926, the Communist Party–controlled ILGWU brought in the gangster Arnold Rothstein to end a disastrous strike.84 Later Jewish gangsters graduated to more sophisticated labor racketeering. In 1936, Louis Buchalter and his friend Jacob “Gurrah” Shapiro were convicted of violating the Sherman Antitrust Act by restricting competition in the fur-dressing trade.85 Buchalter and his henchmen were later found guilty of murder for the slaying of Joseph Rosen, a candy-store owner who was cooperating in an investigation. They were electrocuted at Sing Sing in 1944.86

Italians who grew up in Lower Manhattan were familiar with the needles trades around them. Indeed, Joe Masseria and Charlie Luciano worked briefly in the industry before they were mafiosi. The Gagliano Family had held interests in piecework shops since the early 1930s.87

By the time the Mafia came to the forefront, the ILGWU was under the leadership of David Dubinsky, a dynamic unionist with a record of fighting both Communists and gangsters. The ILGWU became a strong union that prevented the mob from gaining control over its upper-level administration. But even Dubinsky gave up on some areas of the union, like Local 102, a trucking local hopelessly lost to gangsters.88

Mafiosi end-ran the ILGWU by diverting production to their own mob-owned shops. Joe Valachi described how he kept his dress shop union-free. “I never belonged in any union,” Valachi recalled. “If I got in trouble, any union organizer came around, all I had to do was call up John Dio or Tommy Dio and all my troubles were straightened out.”89 By shutting out the ILWGU, these garment contractors held major competitive advantages over rival companies.

“Not to the Bothered by the Union”

Rosedell Manufacturing Company ran a nonunion garment shop on West 35th Street. In 1948, ILGWU organizer Willie Lurye was leading union picketers outside the company's building. They talked truckers out of crossing the line and slowed deliveries into the factory. Rosedell's owners cast about for someone to deal with their union problem.90

Rosedell's owners were put in contact with Benedict Macri. Macri had served as a front man for Albert Anastasia. His brother Vincent Macri was Anastasia's close friend and bodyguard. Rosedell's owners told Macri they wanted either “an International contract or—not to be bothered by the union.” For Macri's services in dealing with the ILGWU, the owners promised Macri a 25 percent share of their business profits.91

Macri had no interest in getting an ILGWU contract. Macri tried to restart operations under the new “Macri-Lee Corporation,” but he still could not get deliveries through his freight entrance. Next, they tried to open a secret cutting room on Tremont Avenue in central Bronx. On Friday, May 6, 1949, the ILGWU picketers got wind of it and went up to the Bronx. According to prosecutors, the pickets slashed about eighteen dresses, infuriating Macri.92

On Monday, May 9, 1949, Willie Lurye was back on the picket line on West 35th Street. In the late afternoon, the ILGWU organizers started to go home. Around 3:00 p.m., Lurye went into the building lobby to make a call from a telephone booth. When Lurye was in the booth, two men trapped him. He screamed in terror as they stabbed him repeatedly. Lurye, bleeding, staggered to the sidewalk. He died the next day. On May 12, 1949, an estimated one hundred thousand New Yorkers participated in or watched the funeral procession down Eighth Avenue. Lurye's grief-stricken father died the following week.93

An eyewitness named Sam Blumenthal told police that he saw two men attacking Lurye with a knife. Blumenthal identified them from photographs as Benedict Macri and John “Scarface” Giusto. Macri, who had gone on the lam within hours after Lurye's murder, surrendered to authorities a year later. Giusto never returned.94

October 1951, People against Macri, Court of General Sessions, Manhattan

On October 11, 1951, the case of People against Benedict Macri commenced in a packed courtroom in Manhattan. The prosecution's initial witnesses testified as expected, establishing Macri's motives and movements that Monday. Then shockingly, the key eyewitnesses to the murder changed their stories on the stand. Sam Blumenthal developed amnesia:

Q Do you remember that you saw, as I have asked you, two men outside the right hand phone booth, moving their hands in the direction of inside that phone booth?

….

A I don't honestly know. In my imagination he did, and yet I'm not sure.

….

Q Did you not tell me, and swear it, on September 21st, 1951, this statement…. “This movement of the hands of the first and second men in the direction of the man in the booth took about a minute.”

….

A I am in doubt of it.

Later in the trial, another prosecution eyewitness seemed to develop vision problems.95

With key eyewitnesses changing their stories, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty. “A lot of strange things have happened,” the judge commented after the verdict. “The witness Blumenthal lost his memory; the witness Weinberg lost his vision.” The judge suggested that these “strange coincidences…might bear some further investigation in the future.”96

Subordination of Perjury

The district attorney's office investigated the witnesses. In March 1952, Sam Blumenthal pled guilty to perjury. Blumenthal admitted that he was approached by George “Muscles” Futterman, a business agent for a mobbed-up jewelry workers’ union. Futterman gave Blumenthal $100, told him to “do what he could not to hurt Macri,” and warned him that he'd be “as good as dead if you don't do what you're told.” Futterman was convicted for subordination of perjury. At sentencing, the judge denounced Futterman as the front man for a “ruthless band of assassins.”97

Although Benedict Macri escaped the law, his mob ties came back on him. In April 1954, Benedict and his brother Vincent Macri went missing after Benedict talked to authorities investigating Albert Anastasia for tax evasion. Vincent's body was found in the trunk of his brother's car. Benedict's body was never found.98

Case Four: Expanding a Mobbed-up Union—Teamsters Local 183 and the Waste Hauling Industry in Westchester County

We look last at how the Mafia spread rackets through mobbed-up unions. This is illustrated by the Cosa Nostra's expansion of its “property-rights” system of waste hauling to the suburbs.

The Mafia and the Waste-Hauling Industry

New York's waste-hauling industry was predominantly Italian, a legacy from when Italian immigrants were relegated to the dirtiest jobs in sanitation. As a young man, Joe Valachi worked as a garbage scow trimmer, the same workers organized by Paolo Vaccarelli. Most commercial waste haulers, or “carting companies,” were small family businesses with a few trucks passed down from father to son. This was a prototypical “fragile” industry.99

In 1929, the City of New York started withdrawing public waste hauling for commercial businesses, viewing it as a public subsidy for private companies. This expanded the market for private waste haulers and, unintentionally, created a fat new target for racketeers.100

The waste-hauling cartel originated in the mid-1930s when the mob organized the carting companies using a Teamsters local and “trade associations.” Mobster Joe Parisi created Teamsters Local 27 and retained Bernard Adelstein to serve as its president, even though Adelstein had no union experience and was an employer-side representative in the food industry. Meanwhile, the “Brooklyn Trade Waste Removers Association” (BTWRA) was organizing small carting companies. Soon political candidates were seeking the BTWRA's support, and officials like District Attorney William O'Dwyer were feting its president.101

The Cosa Nostra used Adelstein's Teamsters union and trade associations to enforce cartels over customer routes. In a perversion of the market, the carting companies “owned” their customers. They fixed routes amongst themselves and charged inflated prices to their captive customers. In March 1947, the New York Commissioner of Investigation dissolved three trade waste associations in New York City for “restricting competition by dividing territory and fixing noncompetitive prices” and for “polic[ing] the industry in order to maintain their monopoly.” It made little difference; the cartels quickly re-emerged with newly labeled associations.102

Vincent “Jimmy” Squillante ran the garbage cartel for the Mangano Family in New York City. Under the guise of the Greater New York Cartmen's Association, Squillante approached carters and promised to solve their labor problems based on his connections to Bernie Adelstein and Albert Anastasia. What Squillante was really offering was the customer allocation system. A carter recalled Squillante's candid explanation:

[Squillante] brought out the point of what we call property rights. In the event a man has a customer or a stop…and that customer moves from that stop, that man claims that empty store and his customer. No matter what customer shall move back into that store, that man has the property rights. No other cartman can go in there and solicit the stop.103

The Mafia's use of Bernie Adelstein's Teamsters local was integral to the scheme. When waste haulers asked why a union was needed for family-owned businesses with “a father and 2 or 3 sons” as employees, the mobster was blunt about the union's real purpose. “No one would take your customers due to the fact that the union would always step in,” Squillante explained.104

The Cosa Nostra was looking for new territories for the garbage racket. So when the City of Yonkers withdrew public waste hauling from commercial establishments in 1949, mobsters were eager to expand to the affluent suburb. They met an immovable object.105

Teamsters Local 456 of Westchester County

John Acropolis was an unusual labor leader. He went to Colgate University on a basketball scholarship, and he became involved with unions while driving trucks in the summer. In 1941, Acropolis was part of a reform slate of candidates who overthrew the incumbents in union elections for Teamsters Local 456 in Westchester County. His strong will earned him the nickname “Little Caesar.” But Acropolis was a sincere unionist who ran a clean local.106

4–3: Nicholas “Cockeyed Nick” Rattenni, ca. 1930. (Used by permission of the NYC Municipal Archives)

Around 1950, mobsters Joe Parisi and Nick “Cockeyed Nick” Rattenni, and Bernie Adelstein of Teamsters Local 27, started muscling in on waste hauling in Westchester County. “They tried to talk us into giving Parisi—that is, local 27—the jurisdiction in Westchester County of all the private carting,” recounted Everett Doyle of Local 456. When Acropolis refused, they took more extreme measures. Adelstein's Teamsters started threatening to put storekeepers out of business unless they switched from Rex Carting, whose workers were represented by Local 456, to a mobbed-up carting company. Rex Carting's office was torched and its trucks burned. Still, Rex Carting and Local 456 continued to hold out.107

2:00 a.m., August 26, 1952, Home of John Acropolis, Yonkers, New York

In the summer of 1952, Joe Parisi and Bernie Adelstein tried to strongarm Acropolis and Doyle at a labor convention in Rochester. After Adelstein outright demanded that Acropolis and Local 456 surrender its representation of Rex Carting, they got into a heated argument:

“You are not that tough. Don't think you are too tough we can't take care of you. Tougher guys than you have been taken care of,” Adelstein threatened.

“It's too bad you are crippled or I would flatten you right here,” Acropolis replied angrily to the peg-legged Adelstein.

Later, Parisi came up to Acropolis's hotel room. “I am through arguing with you,” Parisi intoned. “There is other ways of talking care of you [sic]. We can see that it is done.” Acropolis told him to get out of his room.108

Back home, Acropolis and his fellow union officers started receiving threats over the phone. “Don't park the car when you go home in a dark spot,” they said. “Within the next week four of you are going to die.”109

Two weeks after the Rochester labor convention, around 2 a.m. on August 26, 1952, John Acropolis was opening the door to his home after a long day. Before Acropolis could set down his car keys, someone shot him execution style twice in the back of the head.110 The local police conducted interviews and tried to investigate various mobsters, but they made little progress.111 The case has never been solved.

With Acropolis gone, the mob quickly completed its takeover of waste hauling in Yonkers and the surrounding communities. For the next three decades, Nick Rattenni and his mob allies controlled 90 percent of the commercial waste hauling in Westchester County, reaping millions in inflated fees.112

The Mafia's infiltration of labor unions in the 1930s was the turning point in its rise to power. While Prohibition was a thirteen-year binge, labor racketeering provided a steady diet of profits and power. Our next chapter looks at another new source of profits: the drug trade.