When you first turn on a Mac running OS X 10.10, an Apple logo greets you, soon joined by a skinny, helpful new progress bar that lets you know how much longer you have to wait.

What happens next depends on whether you’re the Mac’s sole proprietor or have to share it with other people in an office, school, or household.

If it’s your own Mac, and you’ve already been through the setup process described in Appendix A, no big deal. You arrive at the OS X desktop.

If it’s a shared Mac, you may encounter the login screen, shown in Figure 1-1. It’s like a portrait gallery, set against a blurry version of your usual desktop picture. Click your icon.

If the Mac asks for your password, type it and then click Log In (or press Return). You arrive at the desktop.

Chapter 13 offers much more on this business of user accounts and logging in.

Note

In certain especially paranoid workplaces, you may not see the rogue’s gallery shown in Figure 1-1. You may just get two text boxes, where you’re supposed to type in your name and password. Without even the icons of known account holders, an evil hacker’s job is that much more difficult.

Figure 1-1. On Macs used by multiple people, this is one of the first things you see upon turning on the computer. Click your name. (If the list is long, you may have to swipe the trackpad to find your name—or just type its first few letters.) Inset: At this point, you’re asked to type in your password. Type it, and then click Log In (or press Return). If you type the wrong password, the box vibrates, in effect shaking its little dialog-box head, suggesting that you guess again.

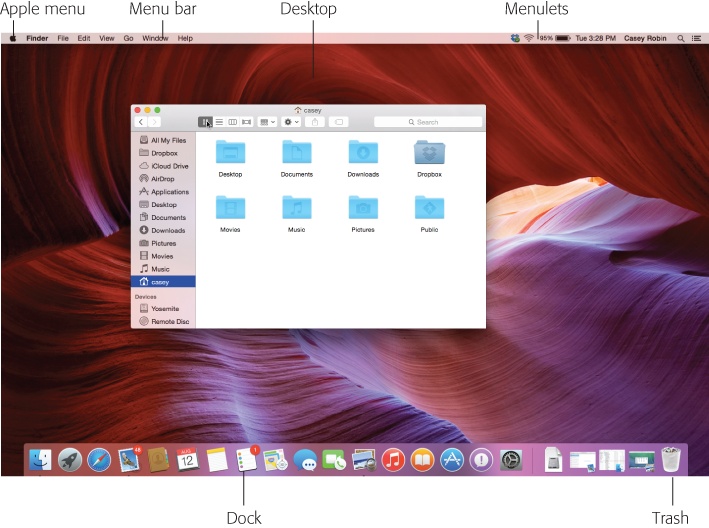

The desktop is the shimmering, three-dimensional OS X landscape shown in Figure 1-2. On a new Mac, it’s covered by a photo of a spectacular, rugged mountain—its name is Half Dome—in Yosemite National Park (get it?). Though, if you upgraded from an earlier version of OS X, you keep whatever desktop picture you had before.

If you’ve ever used a computer before, most of the objects on your screen are nothing more than updated versions of familiar elements. Here’s a quick tour.

Note

If your desktop looks even emptier than this—no menus, no icons, almost nothing on the Dock—then somebody in charge of your Mac has turned on Simple Finder mode for you. Details on Use Simple Finder.

This translucent row of colorful icons is a launcher for the programs, files, folders, and disks you use often—and an indicator to let you know which programs are already open. They appear to rest on a sheet of transparent, smoked glass. In Yosemite, these icons no longer look like realistic, photographic representations of real-world objects; they’ve been redesigned in simplified solid colors.

In principle, the Dock is very simple:

Figure 1-2. The OS X landscape looks like a more futuristic version of the operating systems you know and love. This is just a starting point, however. You can dress it up with a different background picture, adjust your windows in a million ways, and, of course, fill the Dock with only the programs, disks, folders, and files you need.

Programs go on the left side. Everything else goes on the right, including documents, folders, and disks. (Figure 1-2 shows the dividing line.)

You can add a new icon to the Dock by dragging it there. Rearrange Dock icons by dragging them. Remove a Dock icon by dragging it away from the Dock—and enjoy the animated puff of smoke that appears when you release the mouse button. (You can’t, however, remove the icon of a program that’s currently open.)

Click something once to open it. When you click a program’s icon, a tiny, black dot appears under it to let you know it’s open.

When you click a folder’s icon, you get a stack—an arcing row of icons, or a grid of them, that indicates what’s inside. See Pop-Up Dock Folders (“Stacks”) for more on stacks.

Each Dock icon sprouts a pop-up menu. To see the menu, hold the mouse button down on a Dock icon—or right-click it, or two-finger click it. A shortcut menu of useful commands pops right out.

If you have a trackpad, you can view miniatures of all open windows in a program by pointing to its Dock icon and then swiping down with three fingers. Details on how to turn on this feature are on One-App Exposé.

Because the Dock is such a critical component of OS X, Apple has decked it out with enough customization controls to keep you busy experimenting for monthsis . You can change its size, move it to the sides of your screen, hide it entirely, and so on. Chapter 4 contains complete instructions for using and understanding the Dock.

The  menu houses important Mac-wide commands like Sleep, Restart, and Shut Down. They’re always available, no matter which program you’re using.

menu houses important Mac-wide commands like Sleep, Restart, and Shut Down. They’re always available, no matter which program you’re using.

Every popular operating system saves space by concealing its most important commands in menus that drop down. OS X’s menus are especially refined:

They stay down. OS X menus stay open until you click the mouse, trigger a command from the keyboard, or buy a new computer, whichever comes first.

Tip

Actually, menus are even smarter than that. If you give the menu name a quick click, the menu opens and stays open. If you click the menu name and hold the mouse button down for a moment, the menu opens but closes again when you release the button. Apple figures that, in that case, you’re just exploring, reading, or hunting for a certain command.

They’re consistently arranged. The first menu in every program, which appears in bold lettering, tells you at a glance what program you’re in (Safari, Microsoft Word, whatever). The commands in this Application menu include About (which indicates what version of the program you’re using), Preferences, Quit, and commands like Hide Others and Show All (which help control window clutter, as described on Hiding All Other Programs).

In short, all the Application menu’s commands actually pertain to the application you’re using.

The File and Edit menus come next. The File menu contains commands for opening, saving, and closing files. (See the logic?) The Edit menu contains the Cut, Copy, and Paste commands.

The last menu is almost always Help. It opens a miniature Web browser that lets you search the online Mac help files for explanatory text.

You can operate them from the keyboard. Once you’ve clicked open a menu, you can highlight any command in it just by typing the first letter (g for Get Info, for example). (It’s especially great for “Your country” pop-up menus on Web sites, where “United States” is about 200 countries down in the list. You can type united s to jump right to it.)

You can also press Tab to open the next menu, Shift-Tab to open the previous one, and Return to “click” the highlighted command.

Note

The menu bar is partly see-through, for no apparent reason; it’s more evident with some desktop pictures than others. Either way, you can turn off the see-throughness if you want. Open System Preferences→Accessibility→Display, and then turn on “Reduce transparency.”

You can also make the menu bar dark gray with white text—a stark, clear, handsome look; see Sidebar Icon Size.

For years, Apple has encouraged its flock to keep a clean desktop, to get rid of all the icons that many of us leave strewn around. Especially the hard drive icon, which had appeared in the upper-right corner of the screen since the original 1984 Mac.

Today, the Macintosh HD icon doesn’t appear on the screen. “Look,” Apple seems to be saying, “if you want access to your files and folders, just open them directly—from the Dock or from your Home folder (Your Home Folder). Most of the stuff on the hard drive is system files of no interest to you, so let’s just hide that icon, shall we?”

If you’d prefer that the disk icons return to your desktop, then choose Finder→Preferences, click General, and turn on the checkboxes of the disks whose icons you want on the desktop: hard disks, external disks, CDs, and so on.