Most people connect their computers using one of two connection systems: Ethernet or WiFi.

Note

Until recently, Apple had its own name for WiFi: AirPort. That’s what it said in System Preferences→Network, for example, and that’s what the  menulet was called.

menulet was called.

AirPort was a lot cleverer, wordplay-wise, than the meaningless “WiFi.” Unfortunately, not many people realized that AirPort was the same thing as what the rest of the world called WiFi. So at least in the onscreen references, these days, Apple gives AirPort a new name: WiFi.

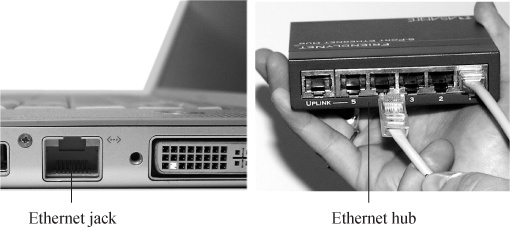

Every Mac (except the MacBook Air) has an Ethernet jack (Figure 14-1). If you connect all the Macs and Ethernet printers in your small office to a central Ethernet hub, switch, or router—a compact, inexpensive box with jacks for five, 10, or even more computers and printers—you’ve got yourself a very fast, very reliable network. (Most people wind up hiding the hub in a closet and running the wiring either along the edges of the room or inside the walls.) You can buy Ethernet cables, plus the hub, at any computer store or, less expensively, from an Internet-based mail-order house; none of this stuff is Mac-specific.

Tip

If you want to connect only two Macs—say, your laptop and your desktop machine—you don’t need an Ethernet hub. Instead, you just need a standard Ethernet cable. Run it directly between the Ethernet jacks of the two computers. Then connect the Macs as described in the box on Networking Without the Network.

Or don’t use Ethernet at all; just use a person-to-person WiFi network.

Figure 14-1. Every Mac except the Air has a built-in Ethernet jack (left). It looks like an overweight telephone jack. It connects to an Ethernet router or hub (right) via an Ethernet cable (also known as Cat 5 or Cat 6), which ends in what looks like an overweight telephone-wire plug (also known as an RJ-45 connector).

Ethernet is the best networking system for many offices. It’s fast, easy, and cheap.

WiFi, known to the geeks as 802.11 and to Apple fans as AirPort, means wireless networking. It’s the technology that lets laptops get online at high speed in any WiFi “hotspot.” Hotspots are everywhere these days: in homes, offices, coffee shops, hotels, airports, and thousands of other places.

When you’re in a WiFi hotspot, your Mac has a very fast connection to the Internet, as though it’s connected to a cable modem or DSL.

Every Mac has WiFi circuitry. It lets you connect to your network and the Internet wirelessly, as long as you’re within about 150 feet of a base station or (as Windows people call it) access point. That box, in turn, must in turn be physically connected to a network and Internet connection.

The base station can take any of these forms:

AirPort base station. Apple’s sleek, white, squarish base stations ($100 to $180) permit as many as 50 computers to connect simultaneously.

The less expensive one, the AirPort Express, is so small it looks like a small white power adapter. It also has a USB jack so you can share a USB printer on the network. It can serve up to 10 computers at once.

A Time Capsule. This Apple gizmo is exactly the same as the AirPort base station, except that it also contains a huge hard drive so that it can back up your Macs automatically over the wired or wireless network.

A wireless broadband router. Linksys, Belkin, and lots of other companies make less expensive WiFi base stations. You can plug the base station into an Ethernet router or hub, thus permitting 10 or 20 wireless-equipped computers, including Macs, to join an existing Ethernet network without wiring. (With all due non-fanboyism, however, Apple’s base stations and software are more polished and satisfying to use.)

Another Mac. Your Mac can also impersonate an AirPort base station. In effect, the Mac becomes a software-based base station, and you save yourself the cost of a separate physical base station.

A modem. A few, proud people still get online by dialing via modem, which is built into some old AirPort base station models. The base station is plugged into a phone jack. Wireless Macs in the house can get online by triggering the base station to dial by remote control.

Tip

If you connect through a modern router or AirPort base station, you already have a great firewall protecting you. You don’t have to turn on OS X’s firewall.

You use the AirPort Utility (in your Applications→Utilities folder) to set up your base station; if you have a typical cable modem or DSL, the setup practically takes care of itself.

Whether you’ve set up your own wireless network or want to hop onto somebody else’s, Chapter 17 has the full scoop on joining WiFi networks.

If you have an iPhone or a similar cellphone, you may be able to get your Mac online even when you’re hundreds of miles from the nearest Ethernet jack or WiFi hotspot. Thanks to tethering, your phone can act as an Internet antenna for your laptop, relying on the slow, expensive, but almost ubiquitous cellular network for its connection. Details are on Cellular Modems.

Apple is busily phasing out the convenient, fast FireWire jacks on its Macs. But if you have two FireWire-equipped Macs, you can create a blazing-fast connection between them with nothing more than a FireWire cable. Details are in the free downloadable appendix to this chapter called “FireWire Networking.” It’s available on this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.