1 Kings

1. FROM DAVID TO AHAB (1 Kg 1:1–22:53)

A. Accession of a younger son (1:1–53). First Kings begins with a point of contrast: back in 1 Samuel the young David is introduced as a man of action and seemingly boundless energy; now, his aged condition creates a situation in which Israel’s king is more acted on than acting.

1:1–4. The opening scene reveals that the servants of David have implemented a search for a young maiden whose body heat will increase the king’s waning temperature (1:1–2). It is unlikely that the servants are proposing a medicinal remedy; on the contrary, this rather appears to be a cover story either to prove the aged king’s virility to a doubting constituency or to produce an heir to the throne. Despite a plethora of offspring, at this point in the story David has not explicitly named his successor.

The servants’ political motivation is evident when Abishag is found, from the village of Shunem, in Issachar—a nice union of north and south (1:3). The servants’ plan, however, is foiled as the king is not intimate with her, and thus the reader concludes that the successor to David’s throne can only be one of his (surviving) sons (1:4).

1:5–10. If there is a power vacuum, Adonijah is determined to step into it. As the oldest son of David—after the untimely deaths of his older brothers—Adonijah enlists the support of key allies (Joab the military commander, plus Abiathar the priest) and holds a feast for leading dignitaries. Like Absalom before him, Adonijah flaunts his royal pretensions with an entourage of chariots and runners, and also like Absalom he receives very little paternal discipline from David (1:5–6a). Factions are apparent in the Davidic court: some officials are invited to join Adonijah, while others (including Nathan the prophet and the younger brother Solomon) are not (1:7–10). The comparison with Absalom—despite good looks and popularity—is an ominous sign for Adonijah’s stately ambitions (1:6b).

1:11–14. One gets the feeling that this is a dangerous place of political maneuvering, an impression enhanced in this scene featuring Nathan’s conference with Bathsheba, the mother of Solomon. Time is of the essence, given that Adonijah is simultaneously hosting a feast with his powerful cadre of associates. After outlining Adonijah’s recent activities—boldly stating that Adonijah has “become king” (1:11)—Nathan instructs Bathsheba to pose a question to King David regarding Solomon’s accession (1:13). No such oath is recorded in 2 Samuel, and a reader may have expected that such a momentous oath would have been mentioned if it had been sworn.

The question remains as to why Nathan would counsel Bathsheba in this manner. We recall that Nathan has had dealings with David and Bathsheba before. In 2 Sm 12:25, Nathan is sent by God to bring a new name for baby Solomon; in the book of Genesis a change of name involves a change of destiny, so Nathan may well infer—reasonably enough—that Solomon is destined to be his father’s successor.

1:15–40. Bathsheba is duly granted an audience in the king’s private chamber, with Abishag in the room, a presence that foregrounds the rivalry of succession (1:15–16). Yet instead of asking the king a question (as Nathan directs), she utters an emphatic statement and explains about the feasting of Adonijah (1:17–21). While she is concluding her story, as if on cue, Nathan arrives and asks a set of questions of his own about the succession (1:22–27).

Whether David ever did swear an oath about Solomon now becomes immaterial: he claims that he did and gives orders that Solomon is to be crowned in his stead (1:28–31). The anointing ceremony is supervised by the trio of Nathan, Benaiah, and Zadok, with Zadok deploying the horn of oil in the midst of considerable pomp—loud enough to make the earth quake (1:32–40).

1:41–53. The tremors can be felt as far away as Adonijah’s banquet, an event taking place simultaneously with Solomon’s anointing ceremony. Jonathan son of Abiathar (of the line of Eli and thus acquainted with rejection!) brings the crushing news to Adonijah, exhaustively detailing the accession of Solomon (1:41–48). This breathless report disperses the guests and sends Adonijah to the horns of the altar, setting the stage for a confrontation between the two brothers (1:49–50).

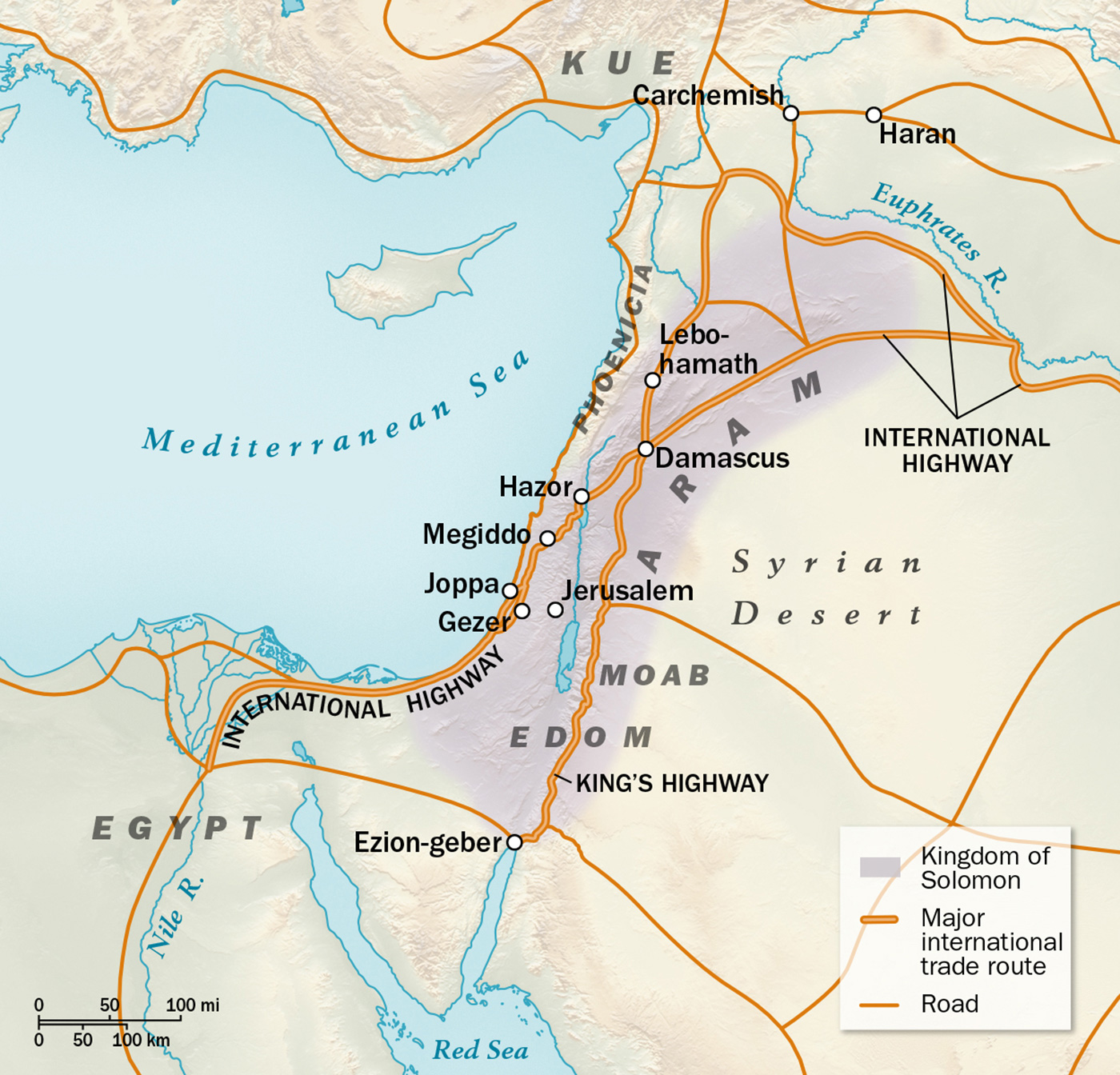

The Kingdom of Solomon and International Trade Routes

Throughout the entire transaction leading up to his enthronement, Solomon has not lifted a finger, so to speak, and certainly has not been allocated any direct speech. In the final scene of the chapter, this is poised to change. With limited options, Adonijah asks for an oath of amnesty (1:51), rather ironic in light of the earlier “oath” issues with Nathan and Bathsheba. However, Solomon does not give any kind of oath to his older brother; instead, he offers conditional terms, to the effect that if Adonijah shows himself to be a worthy man all will be well (but if not, he will die; 1:52–53). One assumes that the freshly crowned Solomon will be the judge of whether or not Adonijah acts in a worthy manner. Solomon’s first words are important for his characterization: the speech to Adonijah shows a glimpse of his wisdom, but one wonders to what ends this wisdom will be used.

B. Security clearance (2:1–46). 2:1–12. David himself mentions Solomon’s “wisdom” during his long speech to his heir (2:6, 9), the last words of David in the narrative. The speech has two parts, beginning with an injunction to walk in the ways of the law (2:2–4), reminiscent of great speeches of the Former Prophets such as Jos 1. David also reiterates the divine promise he was given in 2 Sm 7, but one notices that the language is slightly modified: the promise is unconditional when delivered to David, but here the king stresses that the promise is conditional on his descendants’ faithfulness (2:4). On the one hand, David simply could be extending some hard-earned advice, since his own life could have been much easier had he always walked in the ways of the law. On the other hand, maybe it foreshadows that Solomon himself might have struggles with faithful obedience.

Either way, the second part of the speech gets worse, as David provides a list of leaders Solomon should “deal with”: Joab, Barzillai, and Shimei (2:5–9). While Barzillai is to eat at the royal table, the other two are to be dispatched to Sheol, on rather dubious pretexts it must be said.

The combination of keeping the commandments of the Lord and homicide creates a sense of uneasiness as David breathes his last, and Solomon takes sole possession of Israel’s throne (2:10–12). In 2:12 the narrator highlights that the kingdom is “firmly established,” perhaps undercutting any need for violence toward opponents.

2:13–25. The kingdom may be firmly established, but Adonijah appears to savor some further ambitions (2:13–18). Having been sentenced to virtual house arrest at the end of chapter 1, Adonijah takes a risk in deciding to confer with Bathsheba—but not nearly as great a risk as in requesting Abishag. The reader has already seen that any play on a member of the royal harem is tantamount to a claim on the throne itself, as the actions of Abner (2 Sm 3:7) and Absalom (2 Sm 16:22) grimly illustrate. Whether Adonijah is motivated by love or power, this must be perceived as a bizarre strategy that underestimates his younger brother: why would Solomon consent to such a marriage that strengthens his older brother’s claim?

While Bathsheba agrees to take Adonijah’s suit to her son, we have just seen her execute an audacious undertaking on her son’s behalf, and surely she is not going to give up that easily. In her conference with Solomon (2:19–25) that takes place while both are seated on royal thrones, she undersells the “small” request of Adonijah (which is anything but). Solomon’s reaction is aggressive: he interprets the proposition as treasonous and unleashes a rare double oath toward Adonijah. The double oath is ironic. Adonijah previously wanted an oath from Solomon and was denied; now he gets a twofold portion. Benaiah—who did not attend Adonijah’s party in chapter 1—is summoned to carry out the death sentence, and he will have no shortage of contracts as the rest of the chapter unfolds.

2:26–27. Attention soon shifts to other foes. David did not mention Abiathar, but Solomon takes initiative and banishes the priest to his hometown—though the king says he is worthy of death! While Abiathar’s crime is unstated, one guesses it is that he sided with Adonijah, despite a history of loyalty to David. At the same time, Solomon’s order intersects with a prophetic word spoken against the house of Eli (1 Sm 2:27–36), reminding the reader that such utterances invariably find fulfillment in the narrative. Ironically, Solomon himself will be the subject of such a prophetic word later in the story.

2:28–35. Meanwhile, Joab hears about Abiathar’s treatment and flees to the horns of the altar (2:28). One recalls that David gave Solomon orders about Joab, but why is Joab worthy of death? After all, he has been a staunch ally of David, participating in the cover-up of Uriah’s death, and his liquidation of dangerous challengers such as Abner and Amasa undoubtedly benefited David. A plausible reason is that Joab must die as a penalty for supporting a rival, sending a strong message to any other pretenders that this is how such miscreants are treated in the Solomonic administration. Knowing the game, Joab becomes the second character to cling to the horns of the altar in as many chapters.

Joab does win a moment of reprieve when Benaiah hesitates to strike him down in the inner sanctum, but Benaiah’s conscience is assuaged by a lengthy speech from the king explaining that such a homicide is justifiable, considering Joab’s past conduct (2:29–33). With effective use of some royal hyperbole that cannot be taken at face value, the king’s speech is sufficient to militate against Benaiah’s ethical sensibilities: Joab is struck down, it would seem beside the altar, and for all his loyalty to David is buried “in the wilderness” (2:34). Fittingly enough, after Joab is buried there are two promotions, as Zadok is elevated over Abiathar and Benaiah is put in charge of the army, a position previously held by Joab (2:35).

2:36–46. David had also given instructions about Shimei, a member of the tribe of Benjamin and a supporter of the Saulide regime, one who made the politically incorrect decision to curse David and call him a “man of bloodshed” (2 Sm 16:7). At the fords of the Jordan David swore an oath to Shimei (2 Sm 19:23), but David also said that Solomon was a wise man and would know what to do (1 Kg 2:9). Solomon now addresses Shimei and commands him to build a house and remain in Jerusalem, with a severe restriction on travel (2:36–38). In light of Adonijah’s demise, it might have been wise for Shimei to “hear” (a Hebrew wordplay on the name Shimei) Solomon’s injunction, but chasing some fugitives to Gath, Shimei temporarily leaves the city (2:39–40). It does not appear that Shimei was up to any malfeasance, but like Adonijah, he underestimates Solomon, who is informed of the trip to Gath and launches into another long speech denouncing an opponent and exalting the security of his own throne (2:41–45).

Four-horned incense altar from Megiddo (1000–586 BC). Clinging to the horns of the altar, as Joab does (1 Kg 2:28), indicates a wish for amnesty for those who fear retribution.

When Benaiah is dispatched once more, the reader knows the expected result. What is slightly unexpected is the final line of the chapter (2:46), echoing verse 12, “The king commanded Benaiah son of Jehoiada, and he went out and struck Shimei down, and he died. So the kingdom was established in Solomon’s hand.” The repetition of the verb “establish” serves to reinforce a key truth: Solomon’s ruthless purge was unnecessary, as God had already established his kingdom. While figures like David and Solomon are often glorified in the popular imagination, in fact this narrative functions to draw attention to some of the murky ways in which Solomon uses his gifts. This account of Solomon is not best read as a set of tidy moral lessons; on the contrary, it is an honest and rigorous critique of Israel’s failed leadership.

C. Wise options (3:1–28). 3:1–2. If there have been any lingering doubts with respect to Solomon’s decision making, then such doubts are not eradicated in the opening lines of chapter 3, as Solomon becomes a son-in-law to Pharaoh (3:1). In one respect it is obvious why an ancient Near Eastern king would desire such an alliance, as military and economic advantages would certainly accrue in an arrangement of this type. Yet a main purpose of the exodus is so Israel can be liberated from Egypt, not form partnerships where future ensnarement becomes a possibility. Moreover, the law of Moses—in which Solomon is enjoined to walk—counsels against such marriages (e.g., Dt 7:3). The announcement of a marriage alliance with Pharaoh is thus not mere historical decoration; it is a programmatic statement about how Solomon’s kingship will operate. When the elders of Israel asked for a king “like all the other nations” back in 1 Sm 8, they hardly conceived that they would be getting a player on the world stage.

Solomon makes offerings at the important high place at Gibeon, where the tabernacle is located. God appears to him there in a dream, and Solomon asks for wisdom.

The notice about the people continuing to sacrifice on the high places (3:2)—worship installations perched on hilltops originally having Canaanite roots—underlines the idea of Israel moving toward a kingship model that is indebted to the surrounding nations and stands in uneasy tension with the law.

3:3–15. To be sure, the next section of the chapter begins with a notice that Solomon loves the Lord, although the announcement is slightly qualified since the king himself also frequents the high places (3:3). The way Solomon demonstrates his love is by walking in the “statutes of his father David,” but it will be Solomon’s other loves that prove problematic in due course. For now the king cannot be faulted for quantity of sacrifices, and at the great high place of Gibeon—a spatial setting first introduced in Jos 9—he offers a vast amount (3:4).

The dream at Gibeon, where God appears and invites Solomon to ask for anything he wants (3:5), has often been viewed positively by past interpreters. Indeed, Solomon’s response is effusive and correct: he asks for a “receptive heart” (literally, a “listening heart,” which could also be translated “obedient heart”; 3:6–9). God’s response (3:10–14) is equally long, and on the surface, it looks like a commendation for Solomon’s choosing wisdom over riches, long life, or the death of his enemies (although there cannot be too many enemies left in Israel after the purge in chap. 2). But the fact that God gives him riches and honor anyway can be read in two ways: it might be a sign of approval for the king, or it might be a test. How will Solomon handle the gifts that God bestows? Will he stay faithful until the end of his long life?

Solomon’s reign begins with the positive note that he “loved the LORD by walking in the statutes of his father David” (1 Kg 3:3). By the end of his reign, however, Solomon’s many wives have turned him away to their many gods, and we are told that “he was not wholeheartedly devoted to the LORD his God, as his father David had been” (1Kg 11:4).

3:16–28. Solomon’s wisdom is immediately put to the test, as two prostitutes bring a challenging suit before the king. In the absence of any witnesses or DNA testing, it is a matter for the king to decide between the two claimants. The ingenious solution of calling for the sword (3:24) not only resolves the maternal mystery but also marks the first time in Solomon’s career that the sword will have been used for a positive purpose (as opposed to slaying political rivals).

The public opinion poll at the end of the chapter is revealing: the people “stood in awe of” the king, aware that he has been given wisdom from God (3:28), and they no doubt hope that such responsibility will not be abused.

D. Constructive criticism (4:1–10:29). We assume this text is written for an audience that has experienced the crisis of Jerusalem’s collapse, as an unflinching narrative designed to rebuild the faith of Israel in exile and beyond. Up to this point in 1 Kings, Solomon has established his kingdom and been given tremendous gifts, though small seeds of doubt have also been planted.

4:1–6. The next major section of the narrative (4:1–34) recounts the highlights of the reign. Amid great construction projects, a critical element will emerge as well. At first glance chapter 4 might appear to be just some mundane lists, but in fact there are some important components of the plot contained here. For instance, the opening list (4:1–6) provides a directory of the king’s administrative captains, and several names stick out. Abiathar the priest is still officially on the books (despite banishment), and there is a reminder that Benaiah has been promoted over the army (loyalty seems to be a common thread in the rest of Solomon’s council) (4:4). Almost hidden at the end of the list is Adoniram, in charge of the forced labor (cf. 2 Sm 20:24, a policy started under David; 4:6). The term “forced labor” ominously appeared in Ex 1:11 and will become a central grievance that precipitates the division of the kingdom in chapter 12. In terms of genre, scholars draw attention to similar lists of offices from Egyptian and Assyrian kings, a further indication that Solomon’s court is modeled on the surrounding nations.

4:7–28. The next itemization is of the twelve “deputies,” whose designated tasks include providing daily bread for the burgeoning royal house (4:7–19) and collecting revenues. The stress on surnames and Solomon’s own family suggests a degree of patronage, and conspicuous by its absence is any mention of Judah. Recent commentators point out that the king overhauls the taxation system by restructuring the traditional tribal arrangement into new taxation districts. If there are going to be exciting building projects, someone has to pay for them. The political advantage of changing the boundaries is clear: old party lines and borders are shifted, and the king enjoys increased centralization and a streamlined method of ensuring monthly income.

Regardless of one’s assessment of the ethical ramifications of Solomon’s highly organized system of taxation, the success of the scheme is beyond dispute (4:20–28). From the Euphrates to Egypt, there is sumptuous prosperity, a blossoming court, and an absence of foreign incursions, and the district governors are able to collect a vast amount of food. Still, there is a note slipped in about a vast number of horses (4:26), something warned against in Dt 17:16. The people are living in security, but at what price, and for how long?

4:29–34. The cosmopolitan dimension of Solomon’s court is emphasized in the final section of chapter 4. The report underscores the king’s God-endowed wisdom, which exceeds the greatest sages of the day, and his far-reaching fame (4:29–31). Solomon’s intellectual authority extends even to matters of flora and fauna, with no shortage of audience. Even foreign kings journey to hear this original Renaissance man, a composer of songs and proverbs (4:32–34). A key question remains: how will these remarkable capabilities and the extraordinary gift of such wisdom be used? In 4:29 Solomon has “understanding” (literally, “broadness of mind/heart).” In Pr 21:4, ironically, the same phrase is translated “arrogant heart.” There is a short distance, it would seem, between broadness of mind and arrogance.

5:1–6. The next phase of the narrative (5:1–7:51) outlines the construction projects (palace and temple), but amid all the architectural glory there will also be a subtle criticism of the royal administration. Without much background information, we learn that King Hiram of Tyre sends envoys to Solomon (5:1), having heard of his accession. The city of Tyre was a thriving commercial and colonial center (see Jos 19:29). This is not Hiram’s first appearance in the Former Prophets. Back in 2 Sm 5, an unprompted Hiram sent timber and craftsmen to build a palace for David. Here he sends a delegation to Solomon, and the narrator informs us that he “had always been friends with” (literally “loved”) David—the same verb used to describe Solomon’s “love” for the Lord (1 Kg 3:3).

Hiram does not verbalize any message, so the reader is left to infer what Hiram is really after. Solomon, however, does respond in his typically lengthy manner (5:2–6), and he starts by bringing up the temple. This is Solomon’s first explicit mention of the temple, and it is spoken to a foreign king. Solomon asserts that David was unable to build a temple because of besetting wars (5:3), and we have to refer back to 2 Sm 7 to figure out if this is a valid claim. Regardless, Solomon is interested in the cedars of Lebanon and skilled workers (5:6). The cedars of Lebanon will shortly become a prophetic metaphor of towering pride (e.g., Is 2:13; Zch 11:1).

5:7–18. Hiram’s initial response is an outburst of praise (5:7), surprising in the mouth of a foreign monarch. Hiram then delineates what he will do (float the logs by sea) and finally mentions his own expectations in the transaction: food for his household (5:8–9). A number of commentators argue that Hiram gets the better of the deal, but Solomon is willing to make it because of the unique quality of the timber. He wants, in other words, both the materials and the highly skilled artisans that Hiram could supply, and in return provides a huge quantity of produce for Hiram’s court (5:10–12). We have seen a marriage arrangement with Egypt; now there is a northern alliance. Pharaoh will prove a rather ruthless father-in-law, and while Hiram will never invade Israel, his presence will find its way into the very center of Israelite worship. [Phoenicia]

In terms of Solomon’s preparations for building (5:13–18), the king gathers a workforce of “forced laborers” (again the same word as in Ex 1:11). But at least there are rotating crews, who have superintendents in charge. The king appears to be acting unilaterally, since there is no mention of prophets or priests. Israel certainly has a king like the other nations—hopefully Israel’s worship will be different.

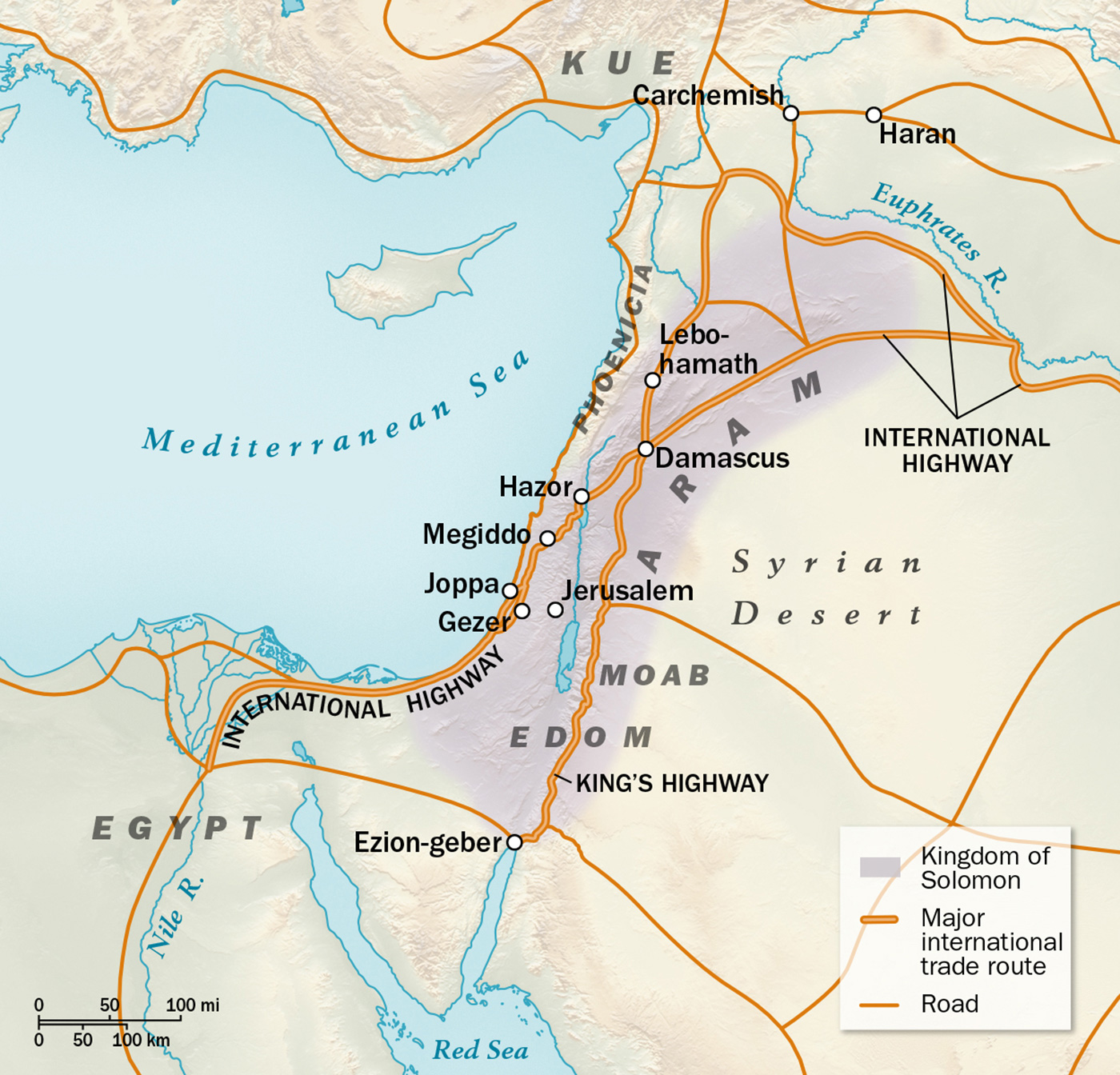

The construction of Solomon’s temple (1 Kg 5–9) contrasts dramatically with the construction of the tabernacle (Ex 25–31; 35–40) in regard to direct input from God and the motivation of the workers and the people.

6:1. Formal commencement of temple construction is prefaced with an important temporal notice. The project begins 480 years after the exodus, locating it at roughly the halfway point between the exodus from Egypt and exile to Babylon. How have the people of Israel fared in the promised land? Have they received a passing grade? The temple project thus becomes a type of midterm exam of Israel’s faithfulness. Further, construction begins in the month of “Ziv, which is the second month.” Here two different calendars are conflated: the old Canaanite agricultural calendar (“Ziv”) and also Babylonian (“the second month”). The halfway point between (past) captivity in Egypt and (future) captivity in Babylon is brought to the fore just as the building begins.

6:2–10. Starting with the external structure, the size of the edifice is delineated. A careful sketch of the dimensions is given, including windows (for natural lighting or ventilation) and side chambers. There is also a note about tools not to be used in the temple precinct, creating a sacred ambiance even during construction (6:7). Yet even in this floor-to-ceiling description some scholars are uneasy, as they believe that aspects of the blueprints have been borrowed from architectural models of the surrounding nations, including Canaanite and Phoenician designs. Since Hiram’s workers are involved, this would not be overly surprising.

6:11–13. The pivot point of this section comes in the form of an unmediated divine word, an interruption of sorts directly from God to Solomon. The chapter is built around this theological utterance, where God furnishes the king with a careful warning by means of an “if . . . then” equation. If the king does not walk with God, then it is possible that God will abandon his people, and therefore even the nicest temple does not grant immunity from obedience.

6:14–38. There is no recorded response from the normally loquacious Solomon to this divine word. Instead, the tour of the building site continues (6:14–36) with an almost bewildering degree of ornate specificity. While it is easy to get lost amid the details, at least “the ark” has considerable prominence and functions as a reminder of God’s provision, promise, and presence (6:19). One hopes that God’s word of caution is not lost in the midst of the tour, but it is possible that occasionally God’s people are more caught up with building programs than relationship and covenant.

The concluding lines of the chapter, though, imply that there is much to admire in this project (6:37–38). The garden plants (flowers and palm trees) and cherubim remind us of the creation narrative, and the reference to “seven” years to “complete” the sanctuary is the same language used in the opening chapters of Genesis. If the fidelity of the king and the worshiping community is as pure as the gold used in the temple, then there is reason for optimism at this key point in Israel’s history.

7:1. The next section begins with another temporal notice, informing the reader that Solomon took thirteen years to build his own house. On the one hand, it might be a simple matter of practicality: the palace is vast and therefore requires more time. On the other hand, there could be a subtle comment on the king’s priorities, and where his attention will eventually be diverted.

7:2–12. What cannot be denied is the impressiveness of the palace. The central palace is a massive structure that must have been quite a feat of engineering. The “palace” is not limited to a single building; included in this larger development are centers of public administration, with courtyards, the “Hall of the Throne,” and a separate residence for Pharaoh’s daughter (a reminder of the marriage alliance with Egypt; 7:6–8). Historians inform us that Egyptian monarchs were not quick to give their daughters in marriage, so perhaps Pharaoh’s daughter is worthy of special treatment in Solomon’s harem. Erecting the palace compound must have been a very expensive undertaking, since its size virtually dwarfs the temple. Is the temple the most noticeable structure in Jerusalem or more of an appendage in the royal facility?

7:13–51. After the palatial digression, the interior design of the temple becomes the focus. A signal moment is the arrival of Hiram, expressly summoned by Solomon. Hiram lays claim to an international pedigree: his mother is a “widow” from the northern tribe of Naphtali, while his father was a skilled artisan from Tyre—thus Hiram can boast of having both Israelite and Phoenician roots (7:13–14). Hiram may have had a hybrid genealogy, but there is no doubting his considerable talents, attested by the substantial catalog of his works: the central pillars (emblematically named Jachin [“He Will Establish”] and Boaz [“In Him Is Strength”], together forming a sentence: “May he [the Lord] establish strength in him [Solomon]”; 7:15–22), the basin (a water tank, perhaps symbolizing how chaos is subdued in the sanctuary; it is also referred to as the “sea” [see the CSB footnote for 7:23]; 7:23–26), along with movable stands and equipment (ideally a celebration of the Lord’s kingship; 7:27–40). During this guided tour of the temple furnishings it seems as if the reader is given the king’s perspective of these magnificent works. We trust that all is done with genuine piety and not with a desire to keep up with the other nations.

Hiram’s consultancy draws to a close with an inventory of his aesthetically pleasing designs (7:41–50), along with a dedication of the objects collected during David’s (many) battles (7:51), suggesting that the treasuries are well stocked and the temple is a place of material prosperity.

8:1–11. Even though two long chapters describe the building and contents of the temple, nothing substantial has yet happened. That is poised to change in the next part of the narrative, a stretch of text that describes the first activities and ceremonies in the newly built house. The king summons the elders during the month of “Ethanim” (seventh month; 8:1–2). Coinciding with the Festival of Shelters, this is an ideal time to bring the ark into the temple due to the number of people in the city and the sense of occasion that the feast carries. Among the assembled dignitaries are representatives of the “tribes” of Israel—rather than the reorganized tax districts enumerated in chapter 4—as well as priests and Levites (a group that has not been prominent so far in Solomon’s reign; 8:3–4). The temple is essentially publicized as the successor to the portable sanctuary and betokens that “place” described in Deuteronomy (e.g., 12:5). In the midst of the ceremony is a prompt from the narrator that the ark is empty except for the tablets of the law (8:9), reinforcing the obligation of obedience. As the sanctuary is filled with divine glory (echoing Ex 40), there is a powerful reminder of God’s commitment to his people (8:10–11).

8:12–21. Despite a bevy of priests on hand, it is the king who presides as the master of ceremonies. Just before moving into his formal address, Solomon supplies a quotation (see Dt 4:11) in response to the enveloping presence of God, followed by his own comment that God will reside in the temple “forever” (8:12–13). In light of the end of 2 Kings, God certainly will not dwell there forever, but it is an apt quotation for the occasion. Along with the requisite praise, Solomon’s address also features a considerable amount of emphasis on the electoral status of the Davidic line (8:14–21). Although the success of the ceremony cannot be refuted, the opportunity is also taken (in this very public setting) to promote Solomon’s kingship. It would probably be unfair to say that the king’s opening words are overtly political, but at the same time—given all the elders who are assembled, from a host of interest groups—the publicity cannot hurt.

8:22–66. Solomon’s exhaustive prayer (8:22–53) merits extensive analysis, but several facets can at least be noted: the mention of the conditional dynamic for the Davidic line is laudable; an almost “exilic” spirituality emerges; there is an inclusive embrace of the foreigner; and there is sizable reference to the necessity of individual and corporate forgiveness for crimes and misdemeanors. When the prayer as a whole is surveyed, it is evident that Solomon’s public discourse features an impressive theological synthesis that must appease the various interest groups assembled. Even if there is a fair bit of promotion of the Davidic line, there is also an unambiguous recognition of God’s transcendence, and one guesses that the prayer must have had an overwhelmingly positive reception. [Rain]

The concluding stage of the ceremony (8:54–66) comprises a corporate blessing by the king (with a call for fully committed [Hb shalom] hearts), abundant sacrifices, and a joyful dismissal. If the nation can remain this united, then Solomon’s leadership will bequeath an enduring legacy.

9:1–9. After a chapter fraught with spectacle and discourse of great acclaim, a more forceful speech occurs, as God again appears to Solomon (9:1–2), just as at Gibeon in chapter 3, where Solomon asked for a “receptive heart” (3:19). God’s word here begins with a stunning acknowledgment that he has heard the king’s prayer, he has sanctified the temple, and his eyes will always be on it (9:3). But immediately the word continues with an intense admonition about the king’s personal conduct, with a rather ominous mention of serving and paying homage to “other gods” (9:6). The consequences of royal disobedience involve more than the king alone: there are implications for all Israel, and a dire warning of eviction from the land that houses the temple. The glorious “house” that Solomon has just finished building will be desolate; and without theological vigilance, it could become a temple of gloom (9:7–9).

Solomon receives the city of Gezer as a wedding gift (1 Kg 9:16). Its location in the Valley of Aijalon and near the International Highway gives it important strategic value for the defense of Jerusalem.

9:10–23. God’s speech makes it clear that the king’s office is a position of trust. Again, there is no response from Solomon, but it is not accidental that the next part of the chapter unfolds a series of transactions from the king’s reign. Indeed, this section looks like an abrupt switch to a collection of somewhat random miscellany, but this is far from the case; a common thread is woven throughout. The first report is of further dealings with Hiram (9:10–14), without whose assistance there would have been a rather different temple. One immediately recalls that the portable tabernacle in the wilderness was built with freewill offerings of God’s people; by contrast, the permanent temple in Jerusalem was procured through international trade and forced labor. Hiram’s “payoff” in the end is a number of villages in northern Israel; from the exilic point of view, land for gold is not a good investment. Real estate deals are beyond the king’s purview.

In addition to partnership with Hiram, Solomon has also made a marriage alliance with Pharaoh, who proves to be a meddlesome father-in-law (9:16). The plethora of royal building ventures is carried out by means of forced labor, with a range of projects (9:15, 17–23).

9:24–28. The final section of the chapter notes the relocation of Pharaoh’s daughter, Solomon’s religious observances, and naval activities with Hiram. The foray into shipbuilding is a lucrative one, netting Solomon an enormous quantity of gold to deposit in his burgeoning coffer (9:26–28). Overall, however, one senses that this entire section of the text is designed to imply that the king—who has asked for a “receptive heart”—might be acoustically challenged. It has taken twenty years for Solomon to build both temple and palace, but now, at the halfway point of his career, time is running out to avert a plague on both the king’s houses.

10:1–13. The state visit of the iconic queen of Sheba is justly famous, although not much is known about her, and the location of Sheba—possibly in Arabia—is uncertain (mentioned in the Gospels as “the ends of the earth,” e.g., Mt 12:42). An exotic visitor of immense wealth and stature, the queen is almost an alter ego of Solomon (10:2). She comes to test Solomon with “riddles” (10:1), a term most recently seen in the Samson story (Jdg 14:12–19); Israel’s urbane monarch passes the test with flying colors (10:3–5). Her theological affirmations (10:9) on one level are astonishing, but on another level we wonder how much is standard courtly rhetoric, in the same manner as Hiram’s fulsome praise in chapter 5. Since Hiram is parenthetically mentioned in 10:11, the comparison is plausible. Solomon passes the test of the queen of Sheba, but hers is not the only test that the king will face.

10:14–29. The amount of gold that the queen gives Solomon actually pales in comparison to Solomon’s yearly income, outlined in the next section of the chapter (10:14–25). With 666 talents (25 tons) per annum (10:14), the question quickly becomes: What on earth can he do with it all? Solomon does not lack creative ideas, as the gold is used for crafting shields, a massive throne, and household utensils, and as a commodity for international business. Clearly Solomon does not heed the warning of the so-called regulations of the king in Dt 17:16–17 to avoid accumulating gold (see the article “Solomon and the Regulations of the King in Deuteronomy 17”). [Solomon and the Regulations of the King in Deuteronomy 17]

Deuteronomy also warns against the accumulation of horses, yet horses get a lot of attention in the closing stages of this chapter (10:26–29). Notably, the price for importing a horse from Egypt is given in silver, meaning the king can afford lavish numbers because of his gigantic income. In the book of Job the horse is symbolic of war and power. Here in 1 Kg 10 the horse has a similar symbolic dimension entailing military arrogance.

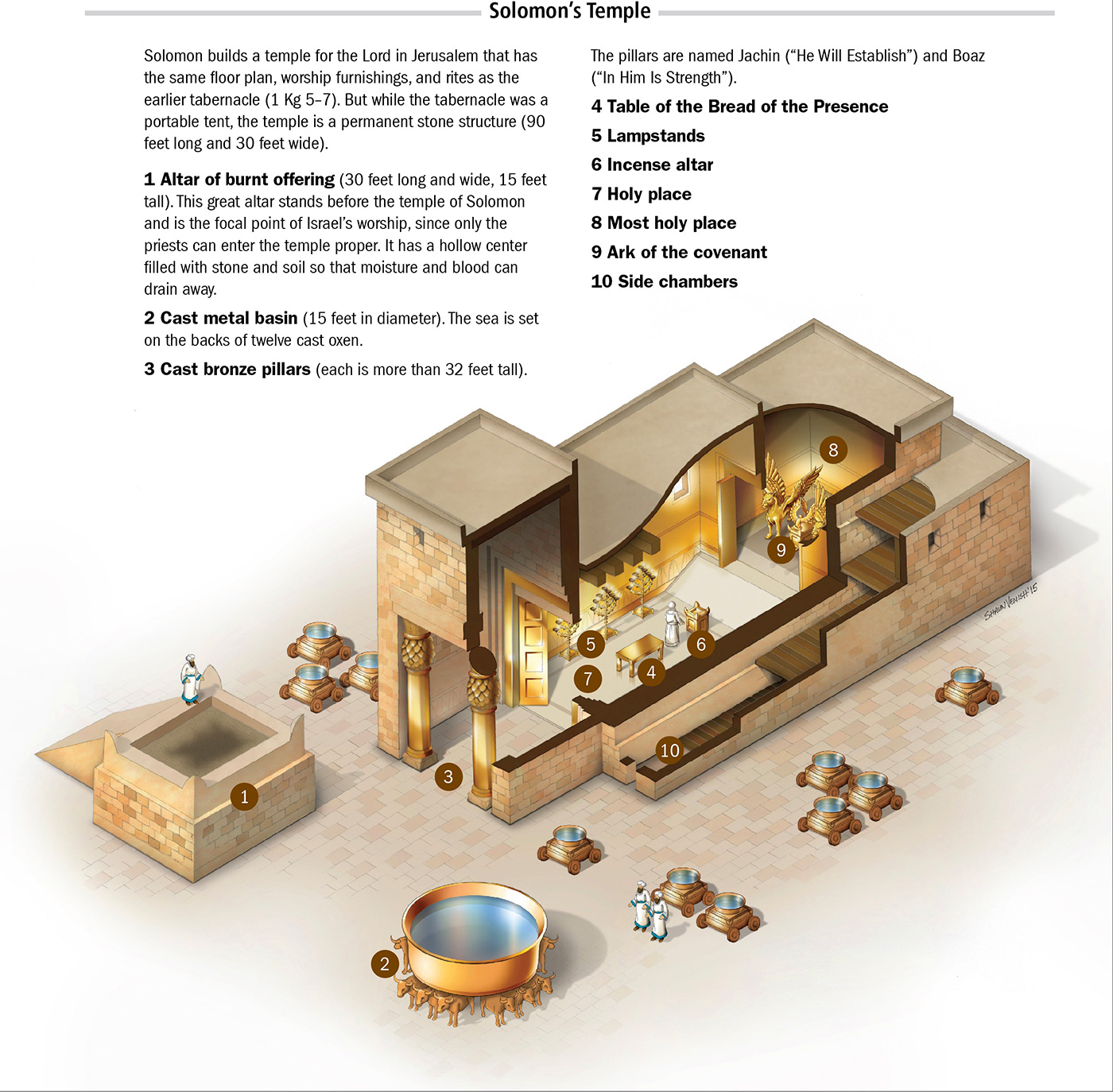

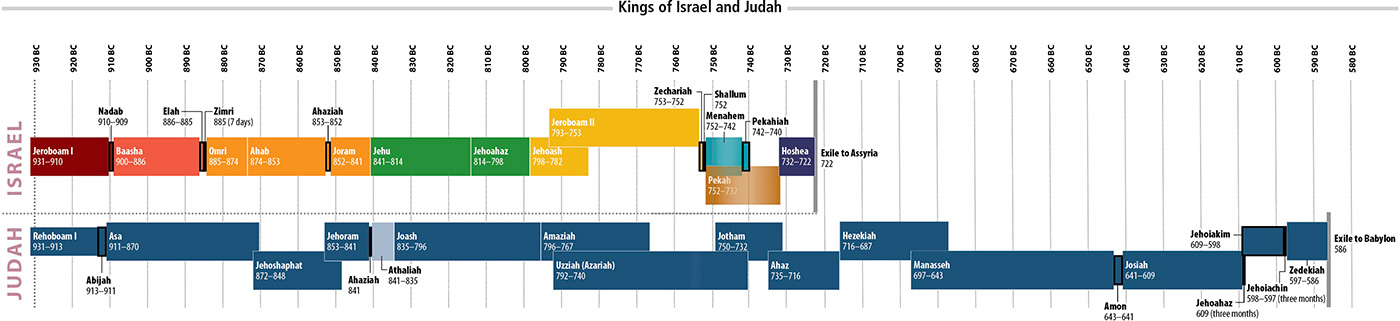

E. Divided heart, divided nation (11:1–12:33). It cannot be an accident that right after a lengthy description of Solomon’s stockpile of gold and horses, we are moved directly into the stage of the narrative commonly referred to as the king’s fall. In fact, “fall” might not be the most accurate term: in light of the warning signs throughout, we may have anticipated that the Solomonic enterprise would come crashing down before too long. Judgment is delayed—surely because of God’s forbearance—but the entire nation is implicated in Solomon’s apostasy.

11:1–13. The first installment begins abruptly: “King Solomon loved many foreign women in addition to Pharaoh’s daughter,” once again in opposition to Dt 17 (11:1). The number of wives is staggering and must be meant to reflect the vast network of political alliances formed by Solomon (11:3). The wives and concubines are only one element, however, as the section continues with a long chronicle of idolatry, mentioning a plethora of deities and installations for their worship that Solomon sponsors, including the spatial setting of the Mount of Olives (11:5, 7–8). Solomon is negatively compared with his father David, who, for all his faults (and he had his share of wives), could not be impeached for idolatry, seemingly the thrust of 11:4, 6. Once more God speaks to Solomon, but this time the warnings are over and a decision is announced: the king’s divided heart will lead to a divided nation (11:9–13). Reminiscent of the earlier conflict between Saul and David, an underling will arise to inherit the kingdom, yet one tribe will remain under the aegis of the Davidic house, on account of the promise articulated in 2 Sm 7.

11:14–25. By means of a flashback (11:14–22) the audience is also informed that Solomon’s kingdom had some serious opposition. When the reader is told that the Lord raised up Hadad of Edom, we note that the specific Hebrew term satan (“enemy,” 11:14) is used, a stunning contrast with Solomon’s earlier declaration to Hiram (5:4) that no “enemy” (satan) can be found on any side. This is a graphic illustration that Solomon’s words can be hollow. In fact, Solomon’s adversaries may be more subtle, since Hadad—like Solomon himself—marries into the Egyptian royal family, and therefore Solomon and Hadad may well share the same father-in-law (11:19–20). Ironically, Hadad is willing to return to his homeland only after the death of the fearsome Joab (11:21), whom Benaiah executes under orders of the king.

As it turns out, Hadad of Edom is not the only adversary, since Rezon of Damascus is also listed as a foe (11:23–25). Neither Rezon nor Hadad is portrayed as actually doing anything, but rather both are seen as creating general mischief. When read in tandem, the account of the careers of Rezon and Hadad anticipates that of the next adversary, Jeroboam. Furthermore, both Rezon and Hadad symbolize and foreshadow God’s use of the Assyrian and Babylonian leaders against the people of Israel.

11:26–40. Solomon’s opponents are not only external but internal as well. Jeroboam is of northern provenance, and his industriousness captures the king’s attention, in such a way that he is rewarded with a key promotion over the northern labor force (11:26–28). But Solomon is not the only one to notice Jeroboam: for no specified reason, Jeroboam receives an oracle, delivered by Ahijah of Shiloh (11:29). Ahijah has no introduction and has not appeared previously in the narrative, but his hometown of Shiloh is certainly acquainted with rejected houses and divine judgment (see 1 Sm 4:12–22; cf. Ps 78:60; Jr 7:12, 14). The crux of Ahijah’s oracle is transmitted by means of a wordplay, as he tears the robe (Hb salmah) to underscore the tearing of the kingdom from Solomon (Hb shelomoh) (11:30–31). One purpose of a wordplay in Hebrew is to signal a reversal of fortune. Like the kingdom of Saul (who is on the wrong end of a garment-tearing episode in 1 Sm 15), Solomon’s kingdom—with all the building projects that impress a consumer culture—is about to be dismantled (11:34–37). We should bear in mind that Ahijah’s word makes clear that Jeroboam’s kingship is conditional from the outset, predicated on his obedience or “listening” (exactly what Solomon has not done). If he is obedient, he will have a lasting kingdom (11:38–39).

No response from Jeroboam is recorded, but Solomon reacts by trying to kill Jeroboam (11:40a). It is a mystery how Solomon finds out, since 11:29 describes Jeroboam and Ahijah as “alone in the open field,” but the remark does foreground the conflict between the king’s power and the prophet’s word that will be with us until the end of 2 Kings. To save his life, Jeroboam—like others before him—flees to Egypt (11:40b). The king of Egypt, as we have seen, has a habit of harboring Solomon’s opponents.

11:41–43. A short obituary for King Solomon closes the chapter, with mention of his deeds and wisdom, but no word about his negligible commitment to orthodoxy and his vacuous worship of the Lord. He is succeeded by his son Rehoboam, but the reader knows that the son has inherited a kingdom on the threshold of partition.

12:1–19. The story of the schism begins in Shechem, most recently the site where the rogue Abimelech was declared king back in Jdg 9. For Rehoboam’s coronation ceremony, Jeroboam returns from Egypt and is present (as de facto leader?) along with a delegation, which lodges its principal complaint: the long hours and harsh working conditions under Solomon are making it difficult to happily dwell under fig and vine (12:1–4). The advice of the elders to Rehoboam indicates that the northerners’ claim is not unreasonable, and the elders’ advocacy of servant leadership—surely not something Solomon ever embodied—reveals their wisdom (12:5–7).

That Rehoboam rejects the elders’ counsel and secures a second opinion from his cronies (described as “young men,” in contrast to the elders) does not speak well of his political acumen (12:8–11). Rehoboam heeds most of their counsel (12:12–14), but 12:15 represents a powerful intersection of the divine will and human folly: it is the Lord’s will that the kingdom should divide, and simultaneously Rehoboam’s inept leadership is the vehicle for the fulfillment of the prophetic word spoken by Ahijah.

The Israelites complain to Rehoboam that his father, Solomon, put a “heavy yoke” on them (1 Kg 12:4). The yoke is a symbol of subjection.

© taviphoto.

Rehoboam’s obstinacy is met with a song (12:16), featuring recycled lyrics first sung in 2 Sm 20 by the leader of the rebel alliance, Sheba son of Bichri. Evidently the song has remained popular in the northern imagination during the reign of Solomon and now resurfaces with a vengeance, as it becomes the rallying cry whereby the kingdom is drastically reduced, just as Ahijah’s prophetic word declared. Sending Adoram—first mentioned in 2 Sm 20, and the one under whose direction the people toiled in forced labor—to calm the cries of the madding crowd may not be the brightest ploy, and Rehoboam barely escapes without being stoned himself (12:18).

12:20–24. In response to the crowning of Jeroboam, the gathering of a substantial host (12:20–21) is either a reflection on Rehoboam’s improved leadership abilities or, more likely, a declaration of loyalty by the south to the line of David. Only a prophetic word spoken by Shemaiah (mentioned only here) averts a civil war (12:22–24). This word is directed to Rehoboam and “the rest of the people,” and the smartest thing Rehoboam does is to listen.

12:25–33. As a virtual opposite, the policy initiatives of Jeroboam are rather different. Jeroboam fortifies Shechem and the northern town of Penuel (as though he is expecting trouble), and a glimpse into Jeroboam’s mind reveals that he is paranoid about southern loyalties (12:25–27). He takes counsel (like Rehoboam) and quickly builds alternative religious objects and sites of worship. Golden calves may not be particularly original (see Ex 32), but their installation at the extremities of the northern kingdom is designed to divert the populace from participating in temple worship at Jerusalem (12:28–30). For similar reasons, Jeroboam also changes the calendar of religious observance, erects high places, and opens the priesthood to non-Levites (12:31–33).

The construction of these two golden calves and the alternative worship centers at Bethel and Dan immediately plunges the new northern kingdom of Israel into idolatry, from which they will never recover. Throughout their history, subsequent kings will be judged as “walking in the ways of Jeroboam and the sin he caused Israel to commit” (e.g., 1 Kg 16:19; cf. 15:34; 16:26; 22:52; 2 Kg 3:3; 10:29; 13:2; 14:24).

F. Northern exposure (13:1–16:34). 13:1–10. The main story line of 1 Kg 13 features an interlude on the prophetic word, an anomalous chapter that in various ways contributes to the overall plot of the narrative. The first scene takes place at Bethel, probably in the shadow of the newly constructed golden calf. It features a confrontation between Jeroboam and an unnamed man of God from Judah (13:1). The unexpected interruption as the new king is paying homage at this alternative place of worship grabs the reader’s attention.

More dramatic than a withered hand and sign fulfilled is the mention of the proper name Josiah, a highly specific prediction and uncommon kind of prophetic utterance that speaks deep into the future (13:2–6). That it is spoken by a man from Judah would have the effect of further unsettling Jeroboam, who we know is paranoid about the people’s loyalty returning to the line of David. This utterance declares that the line of David will not only survive but also eventually produce a spiritual deliverer who will triumph over the very site of idolatrous installation where Jeroboam’s hand has been withered.

Jeroboam’s motives for hospitality and the offer of a gift are not elaborated, but the refusal by the man of God on the grounds of divine commandment should be noted (13:7–10), since (not) eating and drinking is a common element in the next section of the chapter.

13:11–32. The enigmatic dialogue between the man of God from Judah and the old prophet from Bethel yields at least two main points. First, one purpose of the conversation is to raise the issues of false prophecy and the motives of the northern prophet for lying (13:18–19). The motives are complicated by the seemingly legitimate word of the Lord announcing condemnation in 13:20–22, underscoring that God can use even dubious prophets to accomplish his purposes. Second, the animals in the story play an interesting role, as the lion (by not eating) and the donkey (by not bolting) exhibit more self-restraint than the man of God (13:23–28), resulting in a critique of the prophetic office, which will be scrutinized in the days ahead.

The Divided Kingdoms of Israel and Judah

The final lament of the old prophet—and his desire to be buried beside his southern counterpart (13:29–32)—indicates that even the strange old prophet from Bethel understands the efficacy of the prophetic word spoken by the man of God from Judah, and the desire to have his bones next to the bones of the man of God reminds the reader of what will eventually happen to human bones on the altar of Bethel.

13:33–34. By repeating the recalcitrance of Jeroboam in the denouement of this perplexing narrative, the writer alerts us to the ultimate fate of Jeroboam’s house, but even the scare of a withered hand is not enough to dissuade him from a heretical course of action.

14:1–16. From the account of two anonymous prophets we are taken back to a story about a more familiar figure, Ahijah of Shiloh, once more interacting with Jeroboam, although this time by proxy. Jeroboam’s scheme to disguise his wife (14:1–3) fits into the motif of royal disguise that has been seen before (Saul in 1 Sm 28) and will occur later (Ahab in 1 Kg 22), as kings clothe themselves in other raiment in an attempt to thwart a prophetic word. Despite blindness, Ahijah is able to see through the disguise because of a divine word, hence his surprise greeting of Jeroboam’s wife even before she enters the house (14:4–6). Jeroboam’s wife is welcomed with a long oracle of doom that resists an easy summary (14:7–16), but the capstone is that another king will be raised up in place of Jeroboam (who has not, as Ahijah first directed, been obedient), and the nation will be scattered “beyond the Euphrates” (14:15).

14:17–20. No sooner does the ineffectively disguised wife return home than her son dies. He receives a proper funeral, but his death and burial are a grim confirmation that it is hard to deceive a blind (true) prophet of the Lord (14:17–18). Jeroboam is succeeded by Nadab, who inherits a kingdom under judgment (14:19–20). Given the recent events surrounding the prophetic word, the reader knows it is just a matter of time before Jeroboam’s house goes the way of the house of Eli.

14:21–31. A narrative pattern of periodic switching back and forth between north and south leads to a return to Rehoboam. How does this southern king fare while his northern counterpart is on the wrong end of a prophetic utterance? The notice about Jerusalem as the chosen city (14:21) prefaces a catalog of Judah’s transgressions (14:22–24). The southern kingdom of Judah does not appear much more virtuous than the north. Hence it must be the promise to the line of David that allows them to survive, even to the point of incursions by the king of Egypt (14:25–28). Rehoboam’s obituary (14:29–31) includes another reference to his mother (one of his father’s many foreign wives), and the succession of Abijam (Abijah in 2 Ch 13) evokes the recent memory of Jeroboam’s son of a similar name, who died because of the sin of his father.

15:1–8. The opening lines of chapter 15 indicate that time will now largely be measured by kings and their reigns. Abijam’s accession (see 14:31) occurs in Jeroboam’s eighteenth year (15:1), and he quickly builds up a sinful résumé. Rather than being disqualified, however, his line is preserved because of God’s commitment to the line of David, with whom Abijam is unfavorably compared (15:3–4). In rhetorical terms, 15:5 has to be in the same category as David’s last words to Solomon, with the stress on the necessity of obedience. Constant conflict with his northern counterpart is the hallmark of Abijam’s three-year reign (one wonders what happened to the prophetic word of Shemaiah), until he is succeeded by his son Asa (15:6–8).

15:9–24. More narrative space is allocated to the reign of Asa, probably because he has a longer and more fruitful reign. There are some initial fears that Asa and Abijam share the same mother (Maacah), an incestuous tension (15:10; see the CSB footnote; see also 15:2). Regardless, Maacah is dismissed from her position of queen mother when Asa implements a systematic reversal of his father’s policy by eliminating idolatrous paraphernalia (15:11–13). One blemish in an otherwise comprehensive purge is leaving the “high places” intact, sites that we will hear about again in due course (15:14).

The Asa narrative features introductions to two other characters. Baasha will formally enter the stage in the next section of 1 Kg 15 but here gets a brief cameo because of an aggressive campaign to control the key southern access point of Ramah (15:16–17). It is this aggression that leads to the introduction of Ben-hadad, an official title for the Syrian kings, several of whom will appear in the story. Asa uses national resources of palace and temple to broker a “treaty” with Ben-hadad (15:18–19); buying off the Syrian king enables Asa to shift the balance of power, and with his own conscripted labor he reallocates the building material of Ramah to his own defensive fortifications (15:20–22). There is no specific commendation or censure of Asa’s actions here, but such alliances will loom large throughout the narrative of the divided kingdom.

Asherah statuette

© Baker Publishing Group and Dr. James C. Martin. Courtesy of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities and the Cairo Museum.

Asa’s obituary in the closing lines of this section mentions, for the second time in 1 Kings, a document called “the Historical Record of Judah’s Kings” (15:23a), presumably some sort of record the author draws from. Finally, there is the curious note about Asa’s diseased feet (15:23b), and commentators theorize everything from skin disease to venereal disease. After a long reign that spans seven northern kings, this is a painful way for Asa to exit the stage.

15:25–32. In the north, the house of Jeroboam is under a prophetic sentence, so when Nadab inherits the throne of Jeroboam his father, one has guarded expectations. A mere two years pass (15:25) before the prophetic sentence announced by Ahijah of Shiloh is ruthlessly executed by Baasha, ironically the son of (another) Ahijah (15:27–30). Baasha is probably a mere agent in fulfilling the prophetic word, so the reader should be prepared for a similar dynamic unfolding later in the story. As it stands, Baasha is the general of the army when he usurps the throne during a siege, a common theme throughout the history of the northern kingdom. Lacking the same dynastic guarantee as Judah, northern kings will often be deposed by their senior underlings.

15:33–16:7. At some point during the twenty-four-year reign of the usurping Baasha, the prophet Jehu arrives with a strong denunciation (16:1). The fact that Baasha does a good imitation of Jeroboam (15:34) is the initial reason for the prophetic word, as the hitherto unmentioned Jehu announces that the house of Baasha will experience an identical fate (16:2–3). Jehu’s confrontation certainly anticipates prophetic activity in the next major section of 1 Kings (chaps. 17–22), and his phrase “from the dust” (16:2) evokes memories of Hannah’s song in 1 Sm 2:8. Further, the dismal mention of dogs eating the royal corpse(s) will become a familiar refrain before long (16:4).

16:8–14. After Baasha is buried in Tirzah (yet another northern capital city; 16:6), he is succeeded by Elah his son, whose two-year reign marks the end of the short-lived Baasha dynasty (16:8). Just as Baasha conspired against Nadab, so Zimri (one of Elah’s officials) conspires against Baasha’s son. But that is where the comparisons end: Nadab was occupied with a foreign conflict, but Elah meets his doom far closer to home, while getting drunk with a colleague (16:9–10). When Zimri assassinates Elah and reigns in his stead, it is a sober moment, as Jehu’s word about the house of Baasha finds its fulfillment (16:11–13).

16:15–22. The account of Zimri is bizarre for a number of reasons. First, the length of time that he reigns is a meager seven days (16:15), and in that one week he somehow finds time to walk in all the sins of Jeroboam (16:19)—an impressive execution of idolatry. Second, his dismissal begins with rumor, and when Omri (the commander of the military) is crowned, it appears for a moment that there are two kings in the north (16:16–17). Third, Zimri’s incendiary end is recorded from his own point of view (16:18), yielding a suicidal finish to the shortest reign in Israelite history.

For more information on the conspiracy he wrought, we are referred to the northern annals, and primary attention turns to Omri (16:20). He achieves full control once the threat of the rival Tibni expires, after what seems to be a four-year struggle, with the death of Tibni himself (16:21–22).

16:23–28. Although his reign is recorded in only a handful of verses, Omri is the most influential northern king since Jeroboam, while spiritually his legacy in Israel is decidedly negative (16:25–26). Omri’s reign is significant for two reasons. First, he purchases and builds the capital of Samaria, a strategic location (16:24); according to archaeologists, this impressive fortification lasts for the rest of the northern kingdom. Second, Omri sires a modest dynasty (a number of descendants will sit on the throne after him), a reasonable achievement considering the volatility of the north.

16:29–34. The first of Omri’s descendants is Ahab, whose initial claim to fame is that he exceeds in evil all who precede him (16:29–30)—quite an accomplishment, given Jeroboam’s range of sins. The narrative cannot resist a piece of sarcasm: as though it were trivial to commit such atrocities, Ahab plunges even further by marrying Jezebel, the Sidonian princess (16:31). Under the leadership of this royal couple, the worship of Baal and Asherah (the Canaanite storm god and his female consort) flourishes (16:32–33). The manner of Ahab’s introduction sets the stage for the prophetic contest that follows, especially since the final lines of the chapter refer back to Jos 6:26, where a curse is directed at one who attempts to rebuild Jericho. Thus during the preliminary account of Ahab’s reign, we are made aware of the ultimate power of the “word of the LORD,” as Hiel of Bethel belatedly discovers (16:34).

G. Prophetic contests (17:1–22:53). 17:1. After the report about Hiel of Bethel and the fulfillment of the word of the Lord spoken through Joshua many centuries before, Elijah the prophet bursts onto the scene without much introduction (like Ahijah, Shemaiah, and Jehu before him), though he seems to originate from a settlement beyond the Jordan River. Elijah’s initial confrontation with Ahab consists of a single sentence about rain, an important narrative signal of a key theme in this stretch of text. There is a theological confrontation in this text as well: Where does ultimate power reside, in the word of a king or a foreign deity, or in God’s word? Thus the conflict between Ahab and Elijah is brought to the forefront in this struggle: Who controls the rain, Yahweh or Baal? This is the essence of the theological contest between the king Ahab (whose name means “My Father’s Brother”) and the prophet Elijah (whose name means “My God Is the LORD”).

17:2–7. That God immediately directs Elijah to the Wadi Cherith (“Cutoff Creek”) has threefold significance (17:2–3): rain will be cut off until God speaks to Elijah, Elijah will be cut off from Ahab until prompted otherwise, and meanwhile Jezebel will be cutting off the Lord’s prophets in a purge of her own (see 18:4). During this famine, however, Elijah is supplied with food by ravens “in the morning and in the evening” (17:6), reminiscent of Israel’s wilderness experience, when there was no option but for God’s people to be fed by him. Ravens are unclean birds (Dt 14:14) and are therefore a surprising instrument for sustaining the prophet, paving the way for other astonishing moments in this narrative. Compared with the last few chapters, there is a slightly different literary technique deployed here in 1 Kg 17, which comes after the lengthy parade of northern kings and their futilities.

17:8–16. When the water supply of Wadi Cherith is cut off, it creates an opportunity for a shift in spatial setting, and Elijah’s sojourn to the Sidonian widow dovetails with a number of broader themes in the story. The widow, vulnerable in the present, acquainted with grief and loss in the past, is gathering sticks for a last supper amid arid sterility (17:8–12). But she submits to the (counterintuitive) prophetic word and experiences life, as a substitute for death (17:13–16).

In Lk 4:24–26, Jesus refers to Elijah’s visit to the widow of Zarephath, along with Elisha’s healing of Naaman the Syrian, as evidence that his ministry is for more than just the people of Israel, since “no prophet is accepted in his hometown.”

Elijah’s journey deep into Sidonian territory demonstrates God’s sustaining power in a situation akin to “exile,” and the word of the Lord spoken in a distant land transfuses hope in perilous times. In fact, we see in this episode the power of God even beyond the borders of Israel, indeed, in the very backyard of Jezebel! Not only does Jezebel’s god(dess) lack efficacy, but there is some humor here: God hides his prophet deep in the queen’s territory.

17:17–24. Such themes, however, are threatened when the widow’s son takes ill (17:17). Yet the son’s restoration is accomplished through prophetic mediation (17:18–23) and thus encourages a rejection of the royal paradigm espoused by Ahab and Jezebel: what rulers (of any nation) are ultimately helpless to give, the prophetic word achieves.

In this scene the reader hears the testimony of a non-Israelite about the God of Israel and his chosen prophet (17:24). It is the God of Israel who sends Elijah, just as it is the God of Israel who sends rain, who delivers from death, and whose word transcends any other authority.

18:1. By way of review, the first Hebrew word of 1 Kg 17 is “and he said,” centralizing the spoken word that is a key element of this section. Elijah has earlier said to Ahab that there will be no rain “these years,” a vague temporal indicator that suspends royal chronology and replaces it with prophetic time. Noticeably, the next installment of the story begins in the “third year” of prophetic time (18:1), as God announces that he will send rain.

18:2–19. The next segment of the chapter is best viewed through the lens of Obadiah, a figure whose actions and words glance back to the previous chapter and set the stage for the conflict on Mount Carmel. Obadiah is a high-standing member of Ahab’s court, but the meaning of his name (“Servant of the LORD”) reflects a tension: on the one hand he is “in charge of the palace” of Ahab (18:3), but on the other hand, behind the scenes he is aiding the prophets, surely against the wishes of his employers. Obadiah “hid” the prophets and “provided” them with supplies (18:4), just as God earlier told Elijah to “hide” (17:3), and Elijah was “provided for” by the ravens.

Enlisting the help of Obadiah, King Ahab searches for water to keep the animals alive so they do not have to be destroyed (18:5–6). Obadiah must be shocked to find the missing prophet during this quest for unwithered grass, and his long speech provides Elijah with a summary of the events that have taken place while he has been in hiding: Obadiah fears Ahab, but he also fears the Lord (18:9–14). By reciting his résumé to the prophet, Obadiah provides an instance of what literary critics refer to as “contrastive dialogue,” whereby his voluminous outpouring is in answer to a terse command: announce to Ahab, “Elijah is here!” (18:8). Rain will fall only at Elijah’s word, but to the long-suffering Obadiah he is a man of few words.

18:20–40. The confrontation between Elijah and the prophets of Baal on Mount Carmel is a dramatic and well-known episode, and three aspects of Elijah’s words should be highlighted. First, the prophet’s accusation (literally, he asks the people, “How long will you hobble on two crutches?”; see the CSB footnote) encapsulates the vacillating tendencies of the general population (18:21). Ahab and the prophets of Baal are not Elijah’s only opponents in this contest: also on trial is the spiritual paralysis that stems from a lack of real conviction. Obadiah at least shows that it is possible to have some faithfulness even in a brutal regime. By agreeing to the test of fire, the people tacitly agree that they have not been entirely loyal to God (18:22–24).

Second, the mocking voice of Elijah (including pejorative remarks about Baal, such as “perhaps he’s sleeping”) is met with complete silence from the rival deity (18:27–29). This contest is about the power of speech, yet Baal has no voice here. When Elijah rebuilds the altar (18:30–35), the reader may think about the latter part of the book of Isaiah (e.g., chap. 44), where a satirical invective launched at various deities and competing worldviews is followed by a rebuilding of the faith of Israel.

Third, the turning point of the episode is the intercessory prayer of the prophet (18:36–37), and for a community in exile, this surely speaks of the possibility of restoration.

Elijah defeats the prophets of Baal and Asherah on Mount Carmel (1 Kg 18:20–46).

18:41–46. The final scene features a slight ridicule in the warning to Ahab: the king needs to hurry up, because the long-awaited rain will cause his chariot to get stuck in the mud!

19:1–4. When Ahab’s chariot returns home, he reports the news to his wife, Jezebel, whose murderous threats reveal her destructive tendencies (19:1–2). After taking on Ahab, hundreds of false prophets, and the general population, why is Elijah so scared of Jezebel’s threat? Perhaps Jezebel is scarier than anything else Elijah has faced, or her intimidating message is the last straw. Either way, Elijah crosses the southern border with an apparent case of prophetic depression, exclaiming to God, “I have had enough!” (19:3–4).

19:5–18. After the pyrotechnics of Mount Carmel, there is a movement from the prophet’s external conflict to an internal struggle, where he has become like the widow of Sidon and needs to be revived like the widow’s son in chapter 17. Some intriguing parallels begin here (and continue throughout the rest of the chapter) with the desert narratives and the career of Moses in Exodus and Numbers, with a constellation of shared images and words: forty days, the mountain of Horeb, visions, provisions of food by God, and a successor—suggesting that even great leaders need periodic renewal.

Once more Elijah is sustained by a meal, then sent on a journey deep into the wilderness of Israel’s history (19:5–8). As a spatial setting, the mountain of Horeb was a site of revelation, evoking memories of God’s consuming presence. We are unsure how to understand Elijah’s complaint (“I alone am left,” 19:10, 14) in light of Obadiah’s claim of hiding one hundred prophets in caves, but God now proposes to pass by the prophet in the cave at Horeb. Like Moses, Elijah experiences dramatic signs and a thunderous display (19:11–12a). In Elijah’s case, however, they are followed by a “voice, a soft whisper” and a repetition of the question “What are you doing here, Elijah?” (19:12b–13). The prophet’s feeling of isolation is countered by a task list for him—not only providing introductions to some characters who will follow in the story but comforting Elijah as well (19:15–18). The anointing of Elisha as successor, we will see, is vital for the dismantling of Ahab and Jezebel’s kingdom, and thus Elijah’s apprentice will be the prophetic catalyst for the fall of Ahab’s house.

19:19–21. When passing the mantle to Elisha, the senior prophet appears almost gruff with his new protégé. It has been suggested that Elisha hails from a wealthy family (“twelve teams of oxen,” 19:19), and apart from the obvious symbolism of the number twelve and connections with the twelve stones of the previous chapter, this scene implies that Elisha leaves a relatively secure lifestyle for all the risks of the prophetic vocation. That the chapter ends with yet another meal is appropriate (given all the food in 1 Kg 19), but the sacrifice of the oxen confirms that for Elisha there is no going back (19:21).

20:1–12. Given the reinstatement of Elijah, it is noteworthy that neither he nor Elisha features in 1 Kg 20. Instead, we get a different kind of prophetic intervention in this chapter, prompted by the aggression of Ben-hadad and his allies. The considerable demands of Ben-hadad give the impression that he has some leverage (20:1–3); the backstory would be that Israel is experiencing foreign hostilities under Ahab, and therefore abandoning orthodoxy does not always bring socioeconomic benefits. Some witty repartee between the two kings indicates that Ahab has a sense of humor (20:4–12), but it really looks like he is about to get horsewhipped.

20:13–22. Despite Elijah’s protest that he is the only one left, an anonymous prophet confronts Ahab with an announcement of improbable victory (20:13–14). Certainly Ben-hadad is not overly stressed, as we infer from his drunken babble as he imbibes in his tent at high noon with his thirty-two royal allies (20:16–18). As predicted by the prophet, the purpose of Ahab’s subsequent victory is to acquaint the king with this reality, “I am the LORD” (20:13), and the same prophet alerts Ahab that Ben-hadad will soon attack again (20:22).

20:23–34. As it turns out, the sequel has its own set of surprises, beginning with a snippet of a theological and strategic debate inside the Aramean camp, as the officials claim that Israel has “gods of the hill country” and those drunken kings need to be replaced with some serious soldiers (20:23–25). Even though there is a narrative description of Israel’s army (20:27) compared to the massive Aramean host, an announcement to Ahab from a man of God (probably different from the earlier prophet) again forecasts victory (20:28). Ben-hadad has two lucky escapes despite losing the battle: first, he is not crushed by the wall (which falls like the one in Jericho many years ago; 20:30), and second, he receives a pardon from Ahab (20:31–34).

20:35–43. Normally, showing mercy to an opponent on the ropes is commendable, but here the unexpected release of the royal prisoner of war (after securing a favorable trade agreement) leads to a serious prophetic condemnation in the final scene of the chapter. As in 1 Kg 13, this episode features one prophet deceiving another and an attacking lion (20:35–36). The disguised prophet, unlike Jeroboam’s wife, is successful, eliciting a self-condemning sentence from Ahab, whose response prepares the reader for the next episode (20:37–43).

21:1–16. Ahab has wreaked havoc in Israel through apostasy and by marrying Jezebel; now he turns to appropriating his neighbor’s property (21:1–3). Naboth’s refusal to sell or barter his inheritance is consistent with the law (e.g., Lv 25:23; Nm 27:8–11), yet the king’s reaction, as in the previous chapter (20:43), is to return home “resentful” (21:4).

Ahab does not apply further pressure on Naboth—does he realize that Naboth is simply following the law?—but when he is met by Jezebel (21:5–7) we immediately realize that she is not beholden to Israelite law in the same way. Her reaction to the situation again shows her malevolence, but it is unclear whether Ahab expected this kind of response and that his Sidonian wife would concoct a scheme.

Jezebel’s plan of writing deadly letters (21:8–10) evokes poignant memories of David’s dispatching of Uriah back in 2 Sm 11. This time, however, it is the queen who writes in the king’s name, with her request to employ a pair of “wicked men” (21:10) to liquidate Naboth. The false charge carries a death sentence, and Naboth is duly stoned (21:11–14)—a murder, all because he refuses to sell out. Samuel the prophet warned that vineyards would be taken (see 1 Sm 8:14) if Israel would choose the path of kingship, and such a warning is now a dreadful reality for Naboth (21:15–16).

21:17–26. The elders of the city might be fooled by Jezebel and Ahab, but not God’s prophet Elijah, who unexpectedly arrives to deliver a judgment (21:17–24). The spatial setting for this confrontation is “Naboth’s vineyard,” the very place the crime is set in motion (21:18). Ahab is seemingly held liable for Jezebel’s atrocity, but the latter is not exempt; like her husband, Jezebel will suffer the ignominy of dogs consuming her remains (21:23).

The scene is interrupted with a penetrating aside (21:25–26) about Ahab’s vile conduct, reinforcing a key moment from the start of the chapter: Naboth refuses to sell his property, but Ahab has sold himself to do evil, incited by his wife Jezebel.

21:27–29. The concluding interaction between Elijah and Ahab has a pair of incongruous moments. First, Ahab’s response appears humble, with clothing and deportment customary for those in mourning (21:27). Second, one might be skeptical about Ahab’s humility, but God remarks on the king’s contrition to Elijah—the object of Ahab’s wrath on more than one occasion—and actually expresses commendation (21:28–29). Is there a mitigation of divine wrath? The days of Ahab’s house are numbered, but God’s capacity to extend grace should not be underestimated.

22:1–5. After the interlude at Naboth’s vineyard, the narrative focus returns to the long-standing conflict with Aram, where the southern king Jehoshaphat—who will be formally introduced later in the chapter—appears as an ally of Ahab (22:1–2). Despite sparing Ben-hadad’s life earlier, Ahab is now interested in launching a hostile offensive against the northern outpost of Ramoth-gilead (22:3–4). Jehoshaphat seems to be the weaker partner in this alliance with Ahab against the Arameans, but his abrupt request to first seek God’s counsel indicates that his voice is taken somewhat seriously (22:5).

22:6–12. The reader knows that Ahab and Jezebel sponsor (false) prophets, and it is the compromised response of these employees that prompts Jehoshaphat to request a genuine prophet of the Lord (22:6–7). Ahab’s depiction of Micaiah makes it clear that they have encountered each other in the past (22:8), and Micaiah is summoned before an assembly that is aggressively pro-Ahab and obviously prepared to say or do anything to placate the king (e.g., the goring antics of Zedekiah; 22:9–12).

22:13–28. Evidently Ahab has been trumped by Micaiah’s sarcasm on previous occasions, and it is ironic that the king implores the prophet “not to tell me anything but the truth in the name of the Lord” (emphasis added) in the midst of a plethora of false prophets on the royal payroll (22:13–16). By contrast, Micaiah’s bold oracle informs Ahab that a “lying spirit” has emanated from the divine council and spread falsehood (22:19–23), a rather dramatic theological idea to say the least. Micaiah’s presence must be destabilizing for the rest of the prophets, such that it garners a slap in the face, literally, from the iron-horned Zedekiah (22:24–25; cf. 22:11). Deuteronomy 18:21–22 outlines the test for a prophet, and Micaiah tacitly appeals to this tradition, proclaiming that his word will be authenticated (22:28).

22:29–40. Ahab—under a death sentence from Micaiah—does his best to thwart the prophetic word through disguise (like Jeroboam’s wife in 1 Kg 14) but learns the hard way that it is impossible to outmaneuver a true prophetic utterance (22:30). A seemingly random archer drawing his bow “without taking special aim” sends a bleeding Ahab back to town, where the dogs partake of the fulfillment of Elijah’s earlier word and Micaiah’s recent oracle (22:34–38).

22:41–53. Despite lacking a disguise, Jehoshaphat survives the battle, and several highlights of his reign are recounted (22:41–50), including his building of a fleet of trading ships (22:48–49) and his failure to remove the high places (22:43). Meanwhile, Ahab’s death results in the accession of his son Ahaziah (22:51–53), who inherits his parents’ predilection for worshiping false gods.