Daniel

1. THE PREPARATION OF DANIEL AND HIS FRIENDS (1:1–21)

A. Background (1:1–2). Daniel was exiled in 605 BC, the fourth year of King Jehoiakim, together with a cross section of prominent citizens and craftsmen (Jr 25:1; 46:2). Daniel’s method of reckoning differs from that of the Palestinian system (cf. 2 Kg 23:36–24:2), as he writes “in the third year of the reign of King Jehoiakim of Judah” (1:1). This manner of reckoning is based on the Babylonian system, according to which the first year began with the New Year.

The tragedy of that hour was that “the Lord handed” Jehoiakim, articles from the temple, and prominent citizens into captivity (1:2). This was the beginning of the exile of Judah. The people had sinned, and the Lord had to discipline his rebellious children. A second exile later followed, during which Ezekiel and King Jehoiachin were deported (597 BC). A third exile followed the desolation of Jerusalem and the destruction of the temple (586 BC).

B. Education (1:3–7). 1:3–5. Nebuchadnezzar entrusts Ashpenaz, principal of the royal academy, with the instruction of young Jewish boys in the Babylonian culture, including cuneiform, Aramaic (the official language of the Babylonian Empire), astrology, and mathematics (1:3, 4b). All students at the royal academy are required to have no physical handicap, to be attractive in appearance, to show aptitude for learning, and to be well informed, quick to understand, and qualified to serve in the king’s palace (1:4a).

Daniel’s experience in Babylon has many parallels to Joseph’s in Egypt (Gn 37, 39–45): exile as a young man, temptations, faithfulness to God, interpretation of a king’s dream, and rise to power in a foreign government.

The royal academy is supported by the king, who supplies the students with a daily quota of food and wine (1:5). The curriculum lasts some three years, during which time the young men are to develop into competent statesmen to be used for the advance of the Babylonian kingdom. The royal grant is to perpetuate the Babylonian system of cultural, political, social, and economic values. The education is intended to brainwash the youths and to make them useful Babylonian subjects.

1:6–7. The process of cultural exchange is also evident in the change of names. Daniel (“My Judge Is God”) becomes Belteshazzar (“May Nebo [Bel or Marduk] Protect His Life”). The names of his friends—Hananiah (“Yahweh Has Been Gracious”), Mishael (“Who Is What God Is”), and Azariah (“Yahweh Has Helped”)—are also changed. Hananiah becomes Shadrach (“The Command of Aku” [the Sumerian moon god]), Mishael becomes Meshach (“Who Is What Aku Is”), and Azariah becomes Abednego (“Servant of Nego” [or Nebo/Marduk]).

C. The challenge and Daniel’s service (1:8–21). 1:8–16. The issue of food and drink is highly significant to Daniel and his friends. The Lord has clearly designated certain foods as unclean (Lv 7:22–27; 11:1–47). Moreover, the royal court is closely associated with pagan temples, as food and drink are symbolically dedicated to the gods. Daniel humbly asks for permission not to eat the royal diet (1:8). The court official shows favor and sympathy to Daniel, even though he fears the wrath of the king (1:9–10).

Again Daniel responds with courtesy and understanding regarding the official’s predicament. He requests a test period, during which the power of God’s presence could be made evident in the physical well-being of Daniel and his friends (1:11–13). The youths will eat only vegetables and drink only water for ten days. The Lord is with them; after ten days they look “better and healthier than all the young men who were eating the king’s food” (1:15).

1:17–21. The youths distinguish themselves not only by their food but also by their wisdom (1:17). Daniel becomes prominent among his friends, as he can interpret dreams. The king agrees with Ashpenaz’s favorable assessment of the Judean youths and orders them into his service (1:18–19). Nebuchadnezzar finds them to be superior to his own courtiers (1:20).

The Lord is with this Judean prince in a foreign court. Daniel gains prominence in Babylon’s court over a period of sixty-five years (1:21).

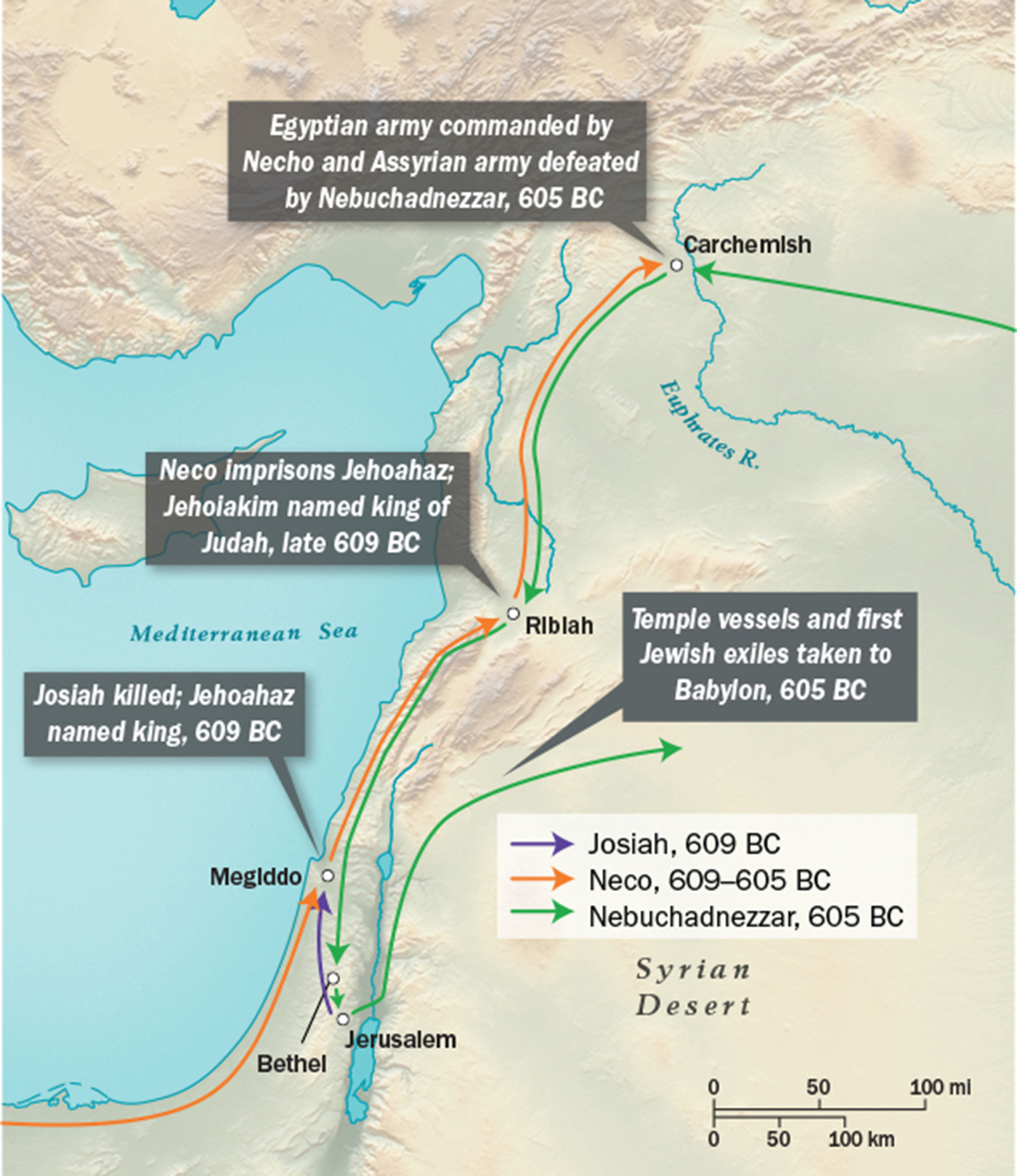

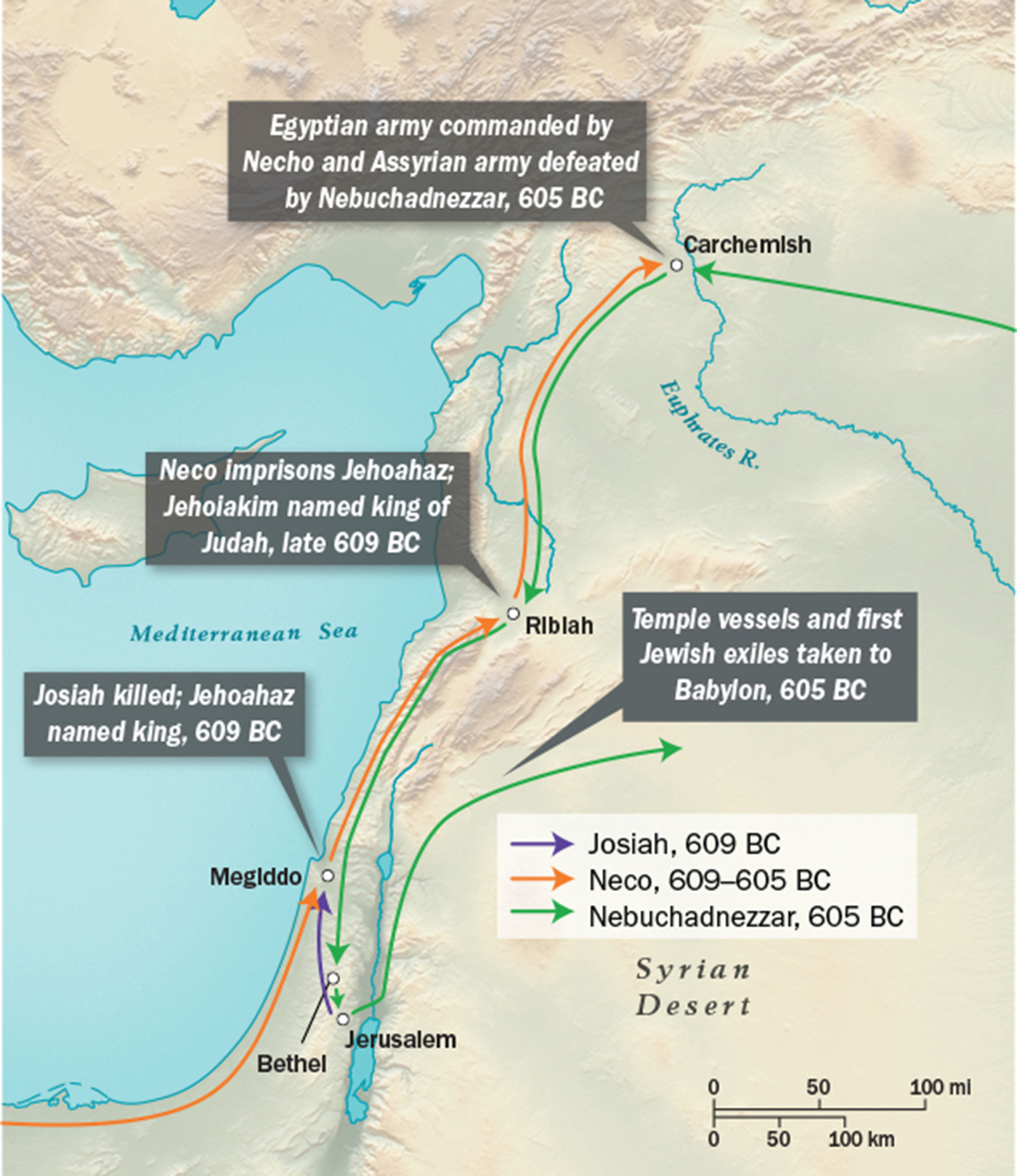

The First Jewish Exiles Taken to Babylon

Nebuchadnezzar’s first military campaign into Judah after defeating the Assyrian and Egyptian armies at Carchemish is short lived because he needs to return quickly to Babylon and secure the throne after his father’s death. Nebuchadnezzar takes the temple vessels and a group of young Judean men, including Daniel, with him to Babylon.

2. NEBUCHADNEZZAR’S DREAM AND DANIEL’S INTERPRETATION: PART ONE (2:1–49)

A. The king and the Chaldeans (2:1–13). 2:1–4. In the second year of Nebuchadnezzar’s reign (604 BC), he has a dream that disturbs him greatly (2:1). He turns to the traditional wisdom of his time by calling on his sages to tell him what his dream means (2:2–3). They are all too ready to please the king, and they ask for the particulars of the dream (2:4). Their request is in Aramaic, the official language of the Babylonian Empire. (Here begins the Aramaic section of Daniel, which continues until 7:28.) [The Four Kingdoms in Daniel 2 and 7]

2:5–13. The wise men are called to explain and interpret a dream but are unable to reconstruct the elements of it. The king repeatedly insists that they tell him both the dream and its interpretation (2:5–7). When the king refuses to change his mind but instead grows more and more agitated (2:8–9), the sages argue that the giving of dreams and their interpretation belongs to the gods (2:10–11). What the king demands is much more than they can handle. Finally, the king orders Arioch, chief of the royal guard, to have all the sages of Babylon executed as impostors and to have their houses destroyed (2:12–13).

B. The king and Daniel (2:14–19). Daniel deals tactfully with Arioch, goes to the king, and receives a delay in the execution (2:14–16). During this time he and his friends pray for God’s mercy. They believe that only their God, “the God of the heavens” (2:18)—a reference to God’s spirituality and universal rule—can help them explain the “mystery.” Daniel does not return to the king until the Lord has revealed the dream and its interpretation and until he has praised his God (2:19).

C. Daniel’s praise (2:20–23). Daniel praises the Lord in a prayer with hymnlike qualities. God’s wisdom and power advance his purposes, as he sovereignly rules over human affairs, even over kings and nations (2:20–21a). He bestows insight on the wise (2:21b). God’s plan for the future lies hidden from human scrutiny but is fully known to him (2:22). This God is no other than the “God of my fathers,” who is faithful to his servants in exile (2:23).

Though Daniel refrains from using the divine name Yahweh, he intimates that the God of the fathers and the great King has a name and that this name will endure “forever and ever” (2:20), even though it may seem to the Babylonians that their gods are victorious.

D. Daniel’s interpretation (2:24–45). 2:24–30. Daniel’s request to be taken to Nebuchadnezzar by Arioch, the king’s hatchet man, is granted (2:24–25). It is possible that Daniel already had a reputation for integrity and for God’s being with him. The manner of Daniel’s speech shows his confidence, and Arioch’s quick response reveals his trust in Daniel.

In the presence of the king, Daniel gives God the glory, as, together with the sages, he admits that “no wise man, medium, magician, or diviner is able to make known to the king the mystery he has asked about” (2:27). Only Daniel’s God can and does reveal mysteries (2:28–29). Daniel humbly admits that he is a mere instrument in God’s hands and that his abilities should not be viewed as native but have been given to him by God (2:30). Then he proceeds to explain the dream.

2:31–35. According to Daniel, the king has seen a colossal statue, whose parts consisted of different materials (2:31–33). But to the king’s amazement, he also saw a supernaturally cut rock (2:34). This rock struck the statue on its feet of iron and clay, smashing them, and made it appear as if the iron, the clay, the bronze, the silver, and the gold were little more than “chaff from the summer threshing floors” (2:35). Nothing remained of the statue. The rock became a huge mountain and filled the whole earth.

2:36–45. Through the dream of the colossal statue consisting of gold, silver, bronze, iron, and feet of iron mingled with clay, the Lord reveals how one empire will succeed another empire: Babylonia, Persia, Greece, and Rome (2:36–40). The resulting instability of the image is represented by the mixing of iron and clay (2:42–43). The image will be completely shattered by the rock, depicting the establishment of God’s eternal kingdom (2:44–45). This vision would have given the exilic community great hope as this eternal kingdom had been given to Israel as a theocratic nation.

All sovereignty is derived from the Lord. He has given Nebuchadnezzar “sovereignty, power, strength, and glory” (2:37). Other kingdoms will arise, each inferior to the preceding one, but whatever the name of the kingdom, its authority is derived from God. In the end, however, no kingdom will fulfill God’s will on earth. Therefore, he will establish the kingdom of God (2:44).

Daniel speaks of the establishment of God’s kingdom. It would be inaugurated more fully after the exile, in the coming of Christ, and in the presence of the Spirit. But it will be gloriously established at the second coming of our Lord.

E. Nebuchadnezzar’s response (2:46–49). Nebuchadnezzar’s response to the revelation signifies recognition of (not conversion to!) Daniel’s God. His confession (2:47) while not insignificant, marks the king as a broad-minded man who willingly makes offering to any god who helps him.

Further, he gives Daniel the honor promised to any wise man who succeeded in telling the dream and in explaining it. Daniel receives a high office and many gifts (2:48–49). Through loyalty to the Lord, careful use of opportunity, and choosing wisely in important issues, Daniel wins a place for himself as a counselor to the king.

3. THE FIERY FURNACE (3:1–30)

3:1–7. Soon after his dream of the statue the king has a colossal image made. It is overlaid with gold, ninety feet high, and nine feet wide (3:1). It probably was erected in honor of Nebo (or Nabu), the patron god of Nebuchadnezzar. The plain of Dura, where the statue is set up, is unknown as a place-name. It simply may have been a place designated for the occasion.

Filled with pride, the king demands that all his officials worship the image he has set up (3:2–3). The king decrees that at the signal of the music, all his subjects proclaim allegiance to him, the Babylonian kingdom, and Nabu (3:4–5). Whoever disobeys will be thrown into a blazing furnace (3:6).

3:8–18. However, the Jews do not submit to this decree. Daniel’s friends (Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego) are readily singled out by the royal counselors, who may still have a vendetta with Daniel (3:8–12). The Chaldeans piously accuse the three Jewish leaders, acknowledging their own complete devotion to the king and thereby further implicating the Jews. They rightly assert that these Jews do not serve any of the Babylonian gods. The king’s anger with the three is mitigated by his concern, which explains his giving them another chance (3:13–15).

The story of the three young men delivered from the fiery furnace (Dn 3:1–30) recalls the words of the prophet Isaiah, promising God’s protecting presence even if we walk through flames (Is 43:2–3).

The contest is actually between Yahweh and the god of Nebuchadnezzar. The Jews express their conviction that their God is able to deliver them (3:16–18). Their faith is so strong that they are determined not to submit to this act of state worship, even if the Lord does not miraculously deliver them.

3:19–23. So desperately does Nebuchadnezzar want his god and state to be victorious over the God of the Jews that, without any further ado, he changes his decree and requires that the oven be made “seven times” hotter (3:19). He then has some of his strongest men throw the Jews into the oven (3:20).

The writer emphasizes the king’s zeal, as everything moves toward the destruction of the three radicals from his empire. The god of Babylon must win! However, in his zeal to destroy the three Jews, the king inadvertently causes his own soldiers, who throw the Jews into the fire, to be killed by the blazing heat of the oven (3:22).

3:24–30. Nebuchadnezzar again faces the superiority of Israel’s God, as he suddenly sees four men walking in the fire (3:24–25). The narrative portrays the transformation of a powerful and rational emperor into an irrational and overzealous maniac. He has to recognize that these men are “servants of the Most High God” (3:26), who “rescued his servants who trusted in him” (3:28). The king promotes Daniel’s friends and promulgates a decree giving protection to Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego (3:29–30).

4. NEBUCHADNEZZAR’S DREAM AND DANIEL’S INTERPRETATION: PART TWO (4:1–37)

A. Nebuchadnezzar’s confession (4:1–3). Nebuchadnezzar’s confession of God’s sovereignty results from a series of events described in 4:4–37. The manner of expression is typical of Israelite poetry and probably reflects editorial reworking. The intent of this section of praise is to show that even a pagan king has to acknowledge that Yahweh is great, that his kingdom extends to all people (4:1), and that “his dominion is from generation to generation” (4:3).

B. The dream and its interpretation (4:4–27). 4:4–9. Nebuchadnezzar had reasons to be proud (4:4). In a short time he had consolidated the power of Babylon from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean and from the Amanus Mountains to the Sinai. He had spent many years on campaigns subduing and conquering. Finally he demonstrated his control in the operation of his administration, which ran smoothly by means of a tight network of officials and checks and balances.

While resting at his palace, he has a dream that terrifies him (4:5). He calls on his trusted officials to interpret the dream, but this time he tells them the dream (4:6–7). Regardless of how hard they try, they cannot interpret it. Then Nebuchadnezzar calls in Daniel, who is known as the “head of the magicians,” trusting in his God-given ability (4:8–9). This time Nebuchadnezzar addresses Daniel with respect.

4:10–18. The king’s dream is of a tree: it is enormous and strong, its top touching the sky; it is visible to the ends of the earth, with beautiful leaves and abundant fruit, providing sustenance and shelter for man and beast (4:10–12). Suddenly an angel decrees that this magnificent tree be cut down and its stump and roots left “with a band of iron and bronze around it” (4:13–15). Further, the angel explains that the king is to behave like an animal and be driven out to live with animals for “seven periods of time” (4:16).

The reason for the execution of this verdict lies in the fidelity of the angels to the great King and his sovereign rule over the kingdoms of this world; he does not put up with anyone who exalts himself to godhood (4:17).

Nebuchadnezzar describes himself as “at ease in my house and flourishing in my palace” (Dn 4:4). The beautiful Ishtar Gate was one of the main entrances to the city of Babylon. A reconstruction is shown here.

4:19–27. Daniel’s response reveals empathy for the king. When the king encourages him to explain the vision, Daniel (or Belteshazzar) responds graciously (4:19). Then he proceeds with the explanation. The tree symbolizes the king and his kingdom (4:20–22). The messenger, who serves the decree of the Most High, forewarns Nebuchadnezzar that only the God of heaven “is ruler over human kingdoms, and he gives them to anyone he wants” (4:25). The tree represents the pride and power of Nebuchadnezzar, which is to be cut down by divine decree until he acknowledges that God rules.

C. Nebuchadnezzar’s humiliation (4:28–37). 4:28–33. A year later the king prides himself on his accomplishments: “Is this not Babylon the Great that I have built to be a royal residence by my vast power and for my majestic glory?” (4:29–30). Babylon was indeed a magnificent city: excellent fortifications, beautiful buildings, and hanging gardens. Its magnificence had become proverbial in a short time, and Nebuchadnezzar had been the driving force behind the rejuvenation of this old kingdom. While he had reasons to be proud, in his pride he overstepped the boundary.

Suddenly he hears a voice and the decree of judgment (4:31–32). He begins to look like an animal (4:33). He eats grass like a bull and lives outdoors. Nebuchadnezzar may well have suffered from the disease known as boanthropy. During the time he suffers from the disease, he is not cared for, and his appearance grows wild.

4:34–37. Only when he recognizes God’s sovereignty and dominion is he restored to the throne (4:34–35). The king confesses that God’s rule is far greater than his. The kingdom of God is an everlasting dominion, extends over all creation, and is absolutely sovereign. Though this public acknowledgment need not be interpreted as conversion from paganism to Yahwism, at least the king is forced to acknowledge Yahweh’s sovereignty (4:37).

5. THE WRITING ON THE WALL (5:1–31)

Upon Nebuchadnezzar’s death in 562, the ruling power changed hands in quick succession due to assassinations and court intrigues. While Nabonidus (556–539 BC) witnessed some growth of Persia on the east, he was unsuccessful in restraining Cyrus. Having been defeated in the field, he retreated, leaving the defense of Babylon to his son or grandson Belshazzar (“May Bel Protect the King”).

5:1–4. The spirit in the city is one of confidence. The banquet of Belshazzar reveals the self-assurance of the king and his nobles, as they drink from the vessels taken from the temple in Jerusalem (5:2–3). He is pagan not only in his drinking but also in his act of sacrilege, as he praises “their gods made of gold and silver, bronze, iron, wood, and stone” (5:4).

5:5–12. The sudden appearance of mysterious writing on the wall greatly disturbs the king and his nobles (5:5–6). He calls in his sages to explain the writing. No one succeeds, even with the promise of being clothed in purple, having a gold chain placed around his neck, and being made the third highest ruler in the kingdom after Nabonidus and Belshazzar (5:7–8). This failure disturbs the king even more (5:9).

The queen—it is uncertain whether she is the grandmother or the queen mother—remembers Daniel, of whom she speaks highly, as Nebuchadnezzar has (5:10–11). She quickly reminds him of Daniel’s ability to interpret dreams, explain riddles, and solve difficult problems (5:12).

5:13–31. Finally, Daniel is called in to interpret the enigmatic writing. The king repeats the offer of rewards and recognizes Daniel’s past (5:13–16). But Daniel refuses the reward (5:17) and freely reads and interprets the writing: “Mene, Mene, Tekel, and Parsin” (“numbered,” “weighed,” “divided”; 5:25–28), signifying that God’s judgment will shortly fall on Babylon and that he has given the authority of Babylon over to Persia. The same God who gave dominion to Nebuchadnezzar has authority to give it to someone else. Daniel reviews some of the events that brought Nebuchadnezzar to the recognition of Daniel’s God (5:18–21).

Belshazzar is more arrogant than Nebuchadnezzar. Daniel presents God’s case against Belshazzar: he is filled with pride; he has desecrated the temple vessels; he has rebelled against the God of heaven (5:22–23). Babylon’s doom is sealed. Despite this oracle of doom Belshazzar keeps his promise, proclaiming Daniel to be the third highest ruler in the kingdom (5:29). The Persians invade the city that night (5:30), using the strategy of cutting off the water from the moat around Babylon. On the fifteenth of Tishri (September), 539 BC, Babylon falls without a siege. Darius (or Gubaru) becomes king of Babylon at the age of sixty-two (5:31). [The Persian Empire]

6. THE LIONS’ DEN (6:1–28)

6:1–9. Darius reorganizes the former Babylonian Empire into 120 satrapies, administered by 120 satraps (6:1). The satraps were directly accountable to the king and to one of three administrative officers, among whom Daniel also served (6:2).

Daniel evokes the ire of the administrators and satraps (6:3–4). They make every effort to find fault with him, but Daniel is blameless. So the royal administrators, prefects, satraps, advisors, and governors come to Darius and ingratiate themselves to him with the request that Darius be the sole object of veneration for thirty days, with failure to do so resulting in penalty of death in the lions’ den (6:6–8). They are successful (6:9).

6:10–18. They are able to trap Daniel in his habitual worship of the God of Israel (6:5). Daniel, who knows about the edict but relies on God to deliver him, regularly and openly prays three times a day at fixed times (6:10). He does not begin to pray when times are hard, but rather he continues his habitual devotion to the Lord and to his temple, which now lay in ruins in Jerusalem. Daniel’s only crime is prayer (6:11). Daniel’s enemies hurriedly report him to the king, demand justice from Darius, and get it (6:12). Upon learning that Daniel is the victim of their plot, Darius understands the motivation for their flattery and is greatly outraged at this miscarriage of justice (6:13–14). But, trapping the king by his own decree, they demand Daniel’s death, reminding Darius of the supremacy of law over loyalty and feelings (6:15).

His opponents persist until Daniel is thrown into the lions’ den (6:16). Darius perceives at least something of the greatness of Daniel’s God. The stone and royal seal ensure that Daniel’s escape from the lions’ den is impossible (6:17). Nevertheless, the king expresses hope that Daniel’s God might deliver him. He spends a restless night full of anxiety (6:18).

6:19–28. As soon as his decree permits, the king rushes to the den and with anxiety calls to see if Daniel is still alive (6:19–20). Daniel speaks and gives glory to God (6:21–22). Daniel’s loyalty extends to both God and the king.

Hearing Daniel’s voice, the king rejoices (6:23). He has Daniel brought out of the den and examined for wounds or scratches; he discovers that the lions have been kept from devouring this servant of God. He has the schemers and their families thrown into the lions’ den, and they are quickly destroyed (6:24).

Further, the king decrees public recognition of Daniel’s God as the God whose kingdom remains forever and whose power manifests itself in deliverance (6:25–27).

Mesopotamian courts often kept lions in cages so that the king could hunt them. The lions of Dn 6 are probably lions kept for that purpose. This Assyrian wall relief depicts the release of a lion for the hunt.

© Baker Publishing Group and Dr. James C. Martin. Courtesy of the British Museum, London, England.

7. VISION OF THE FOUR BEASTS (7:1–28)

A. The vision (7:1–14). 7:1–3. In the first year of Belshazzar (ca. 553/552 BC), Daniel has a vision (7:1), whose message parallels that of the first dream of Nebuchadnezzar (chap. 2). Four beasts, symbolic of the nations (cf. Ps 65:7), come out of “the great sea” (7:2–3). The appearance of the beasts in each vision has both familiar and unusual features.

7:4–6. The lion with the wings of an eagle (7:4) resembles the cherub, protecting the kingship of God above the ark. As it consolidated power, this kingdom believed that it was destined for eternity. But its power being human, it is forcibly removed. Though it appeared to be the kingdom of the gods, the kingdom was as frail as any other human kingdom.

The bear with three ribs in its mouth represents the coalition of powers (7:5). The three ribs between its teeth and its readiness to eat its fill of flesh may symbolize the Persian conquest of Lydia (546 BC), Babylon (539 BC), and Egypt (525 BC).

The third animal has four heads (7:6). These suggest four kingdoms, or the extent of its rule (the proverbial four corners of the world).

7:7–8. The fourth and most terrifying is the beast that oppresses kingdoms (7:7). It has ten horns, from which comes “another horn, a little one,” uprooting three of the original horns (7:8). This horn looks like a human face and is full of pride.

Ten is a symbol of completion and need not be limited to a future kingdom consisting of “ten” nations, which some call a revival of the Roman Empire. This kingdom is to be more powerful, extensive, despotic, and awe-inspiring than the previous kingdoms.

7:9–10. Daniel momentarily interrupts the vision of the animals from the sea to reflect on the vision from heaven. The vision of the human kingdoms gives way to a vision of God (“the Ancient of Days”) enthroned on high as the great king (7:9). Daniel describes God in more detail than any of the prophets before or after him: his clothing is as white as snow; his hair is white like wool. The throne of God is flaming with fire and mobile like a chariot, with wheels ablaze with fire.

The Lord is the great Judge, who is seated to judge the kingdoms of this world. There is no escape from his judgment. A river of fire flows before him (7:10). He is the Lord of Armies, with thousands upon thousands awaiting his command. The acts of people are recorded in his books.

7:11–14. Daniel returns to describe the acts and words of the little horn (7:11a). The pride of this kingdom is self-evident by the arrogant words of the horn (cf. 7:8). Despite its power and onslaught on God’s kingdom, it comes to an end and is burned with fire from God’s chariot (7:11b). The other kingdoms are also stripped of their authority, though they are permitted to rule for a period of time (7:12).

The Ancient of Days gives authority over the remaining kingdoms to “one like a son of man,” who is permitted to approach the throne of the Ancient of Days without harm (7:13). In addition to authority, he is given glory and sovereign power and receives the worship of all nations and peoples of every language (7:14). His kingdom is not temporary or subject to God’s judgment but is an everlasting dominion.

B. Its interpretation (7:15–28). 7:15–22. The visions of the beasts from the sea and the awe-inspiring vision of the glory of God and of his Messiah overwhelm Daniel. He is at a loss to explain what he has just seen (7:15). So he asks an angel for the interpretation (7:16). The four kingdoms symbolize the kingdoms of man, which are transitory; the everlasting kingdom belongs to “the holy ones of the Most High” (7:17–18).

Daniel presses the angel concerning the disturbing vision of the fourth beast (7:19–20). Before the angel can explain, Daniel catches another aspect of the little horn. Not only does he speak arrogantly; he also opposes and persecutes the saints (7:21). It appears that he is victorious over them until the Ancient of Days intervenes on their behalf and judges the horn (7:22). Then the righteous receive their reward: the kingdom.

7:23–25. The angel explains that the fourth beast differs from the others by the intensity of its disregard of the laws of God and humans. It “will devour the whole earth” (7:23). The ten horns symbolize the succession of power (7:24). But the little horn will wrest power from three other kings/kingdoms and will have less regard for human rights and for the law of God than his predecessors. He will wage war with God and with his saints for “a time, times, and half a time” (7:25; a cipher for three and a half years).

Who is this “king” represented by the little horn? Interpretations differ, depending on how one interprets the ten kings (“horns”). He may be the antichrist or the continuity and increase of evil in the end of days. Regardless of the identification, the Messiah will cut him off suddenly and quickly.

7:26–28. This king will be judged as he has judged others (7:26). By the power of God his power will be taken away and completely destroyed. God will finally and victoriously crush the power of the fourth empire and all the kingdoms that arise out of it. Then, the saints will rule with “kingdom, dominion, and greatness” (7:27). The kingdom of God and of his saints will last forever.

Daniel is not relieved by what he has seen or by the interpretation given to him. He remains greatly disturbed and keeps the matter to himself (7:28).

8. VISION OF THE KINGDOMS (8:1–27)

A. The vision (8:1–14). 8:1–8. In the third year of Belshazzar (551/550 BC), Daniel sees himself in a vision in Susa, the Persian capital (8:1–2). There he observes a ram with two long horns standing by the Ulai Canal (8:3). The ram denotes the coalition of power. The ram pushes westward, northward, and southward, gaining greater control and augmenting its absolute power (8:4).

However, the ram’s power is suddenly broken by a male goat with a prominent horn between his eyes (8:5). The goat comes from the west, moves rapidly as if not touching the ground, and charges into the two-horned ram. The two-horned ram is powerless and easily overcome by the goat (8:6–7). The sovereignty of this kingdom is ended when its large horn is broken off, and in its place four prominent horns grow up toward the four winds of heaven (8:8).

8:9–14. Out of one of these four horns grows another horn, which exalts itself against God by turning against (“toward,” 8:9) “the beautiful land” (Israel; cf. Jr 3:19).

This prophecy, like Ezk 38–39 and Zch 12 and 14, reveals the drama of the opposition to the people of God by the powers of this world. Many read the text as speaking of the invasion of the Seleucid (Syrian) king Antiochus IV Epiphanes into Judah, when, due to persecution and sacrilege in the temple for more than three years (1,150 days), the evening and morning sacrifices ceased (8:14). However, even though his defeat marked the end of the suffering brought by this king, the truth is that opposition continues to the very end. John makes this point in Rv 11:2, where “forty-two months” symbolically stands for a period of intense persecution and wickedness. [Abomination of Desolation]

B. Its interpretation (8:15–27). 8:15–19. An angel asks Gabriel to further explain to Daniel the meaning of this vision (8:16). At Gabriel’s approach, Daniel falls down in worship (8:17a), as Ezekiel did at the revelation of God’s glory (Ezk 1:28; 3:23). Daniel is addressed as “son of man.” Gabriel explains that the vision pertains to “the time of the end” (8:17b). Daniel is clearly in a visionary trance (“I fell into a deep sleep,” 8:18). The angel raises him up to his feet to make certain that Daniel will remember the import of the moment.

8:20–26. He explains that the two-horned ram represents the coalition of power under Persia, that the shaggy goat signifies the king of Greece, and that the large horn is the first king (i.e., Alexander the Great) (8:20–21). He further explains that the four horns that supplanted the broken-off horn represent four kingdoms (8:22). From one of the kingdoms “a ruthless king, skilled in intrigue, will come to the throne” (8:23). This king will be powerful in his ability to destroy and especially in his persecution of “the holy people” (8:24).

Many take this to be a description of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who was a master of deception. He opposed the principalities, the spiritual forces protecting God’s interests in the nations, and even the “Prince of princes” (8:25). Yet his fate also lay in God’s hands, as he came to a sudden end. Antiochus died at Tabae (Persia) in 163 BC. Because the vision of “the evenings and the mornings” is the vision of the end and is to be properly sealed up (8:26), a referential connection with Antiochus unnecessarily restricts the range of the prophecy.

8:27. Daniel is so exhausted from this vision that he is sick for several days. He has to excuse himself from doing the king’s business. He does not understand the vision, but he preserves these words for later generations.

9. DANIEL’S PRAYER AND VISION OF THE SEVENTY WEEKS (9:1–27)

A. Daniel’s prayer (9:1–19). 9:1–3. In the first year of Persian rule (539/538 BC), Darius, son of Xerxes (in Hebrew, Ahasuerus) and a Mede by descent, becomes the governor of Babylon (9:1). Daniel is drawn to meditate on the prophecy of Jeremiah (9:2), who was one of the prophets predicting the era of restoration, consisting of covenant renewal, restoration of the people to the land, and the continuous service of the priesthood in the temple (Jr 30–34). Jeremiah also predicted that the Babylonian kingdom was to last seventy years (Jr 25:11–12) and that subsequently Jerusalem would be restored. Daniel longs for the era of restoration, for the establishment of the kingdom of God and of the messianic kingdom. To this end he fasts and prays for the restoration of his people to the land (9:3). [Medes]

9:4–19. Daniel’s prayer consists of confession and petition. In the confession he identifies with the history of his people, with their sin and punishment. The prayer of confession consists of a repetition of four themes: Israel’s rebellious attitude to the law and the prophets, God’s righteousness in judgment, the fulfillment of the curses, and the hope of renewal of divine mercy and grace.

Daniel begins with an affirmation of God’s mercy, inherent in Israel’s confession of who God is (9:4). In contrast Israel has sinned against their covenant God (9:5). They have rejected the prophets (9:6). Therefore the Lord is righteous in his judgment. Yet the disgrace of Israel is apparent wherever they have been scattered (9:7). Their lot has changed by their own doing, but the Lord is still the same (9:9–10). Israel has received the curses of the covenant (9:11; cf. Lv 26:33; Dt 28:63–67). The Lord has been faithful in judgment, even in bringing about the desolation of Jerusalem (9:12). Again Daniel affirms the righteousness of God (9:14).

Daniel throws himself on the mercy of God as he prays for the restoration of Jerusalem, the temple, and God’s presence among his people (9:17–19).

B. God’s response (9:20–27). Daniel prays from the conviction that the Lord has decreed an end to the Babylonian rule. Now that this has taken place, Daniel prays for the speedy restoration of the people, the city, Jerusalem, and the temple (9:20). He has acknowledged the sin of Israel but trusts the Lord to be faithful to his promises.

Suddenly, the angel Gabriel appears to him in a vision (9:21). He was sent to explain God’s plan as soon as Daniel had begun to pray (9:23)! This speedy response is an expression of God’s special love for Daniel. Gabriel explains the seventy weeks and what will take place during that time (see the article “Interpreting the Vision in Daniel 9:24–27”).

10. MESSAGE OF ENCOURAGEMENT (10:1–11:45)

A. Introduction (10:1–3). In the third year of Cyrus (536 BC; 10:1) Daniel is standing by the banks of the Tigris (10:4) when suddenly he receives the revelation of a long period of suffering and persecution. He is so struck by the vision that he fasts and mourns for three weeks (10:2–3).

B. The angel (10:4–11:1). 10:4–9. The vision comes shortly after the celebration of Passover and the Festival of Unleavened Bread (10:4). Daniel is addressed by someone whom he describes in great detail (10:5–6). Daniel is so moved that the people around him are terrified by his appearance; they instantly flee, leaving him alone (10:7–8).

10:10–11:1. The angel has been trying to communicate with Daniel for three weeks but has not been able to until Michael, one of the archangels, overcomes the spiritual power (a demon) over the Persian kingdom (10:12–14). The angelic visitor proclaims God’s peace to Daniel and encourages him with a message pertaining to the end of Persia and the beginning of the rule of Greece (10:19–20). The kingdom of God is established not by flesh and blood but by spiritual powers.

The vision completely overwhelms Daniel. The angel touches him three times to wake him up (10:10, 16, 18). His face turns pale (10:8); he feels helpless, he is speechless, he is filled with anxiety, and he is ready to die (10:15–17). The angel strengthens him physically and assures him that the Lord loves him and wants to reveal to him his plan (10:19). The very resistance he has endured arises from spiritual warfare between the powers of darkness and the kingdom of God. The revelation comes from “the book of truth” (10:21), the record of God’s plan for the progression of the redemption of his people. The angel together with Michael was sent to work out the restoration of the people of God from the moment Cyrus became king over Babylon and Darius was installed as governor (11:1).

C. The vision (11:2–45). 11:2–20. The detailed description of the interrelationship between the kings of the south and the kings of the north in Dn 11 has long challenged biblical scholars. The angel reveals to Daniel that three more kings (Cambyses, Smerdis, Darius Hystaspis?) will rule over Persia. The fourth (Xerxes I?) will try to incorporate Greece into the Persian Empire. Upon the death of Alexander the Great of Greece (“a warrior king,” 11:3), his kingdom was divided into four parts: Macedonia, Thrace, Syria (“the king of the North,” or the Seleucids), and Egypt (“the king of the South,” or the Ptolemies). Daniel 11:5–20 relates the rivalry and wars between the Ptolemies and Seleucids until the appearance of Antiochus Epiphanes.

11:21–45. The Seleucid Antiochus IV (he took on the title Epiphanes, “God Manifest,” and was nicknamed by some Epimanes, “Madman”) could be the “despised person” of 11:21. In his attempt to gain absolute control over Egypt, he was ruthless in his campaigns and encouraged his troops to loot and plunder. His mission against the Ptolemies also failed.

Finally, he aimed his anger at Jerusalem, the temple, and the Jewish people (11:30–35). He desecrated the altar in the temple, set up an image to Zeus (168 BC), and required the Jews to worship the gods of the Greeks. The Lord raised up help (11:34; Judas Maccabeus). The godly Mattathias led the Jews to resist the order to sacrifice to the gods. His son Judas Maccabeus led the insurrection and succeeded by the grace of God in cleansing the temple. The rededication of the altar took place in December 165. This event forms the background of the Hanukkah (“Dedication”) celebration (cf. Jn 10:22).

The Ptolemaic and Seleucid Kingdoms

After the death of Alexander the Great, his kingdom was divided among his four generals (see Dn 11:4). Judea was caught in the middle of the struggle between the Ptolemaic and Seleucid kingdoms for power and territory.

The power represented by Antiochus typifies the spirit of all kings who exalt themselves, doing whatever they please (11:36–37). The description of that king not only applies to Antiochus. It is symbolic of evil. The interpretive difficulty lies in the nature of apocalyptic language, which mixes historical details with a grand picture of opposition by the kingdoms of this world for the purpose of assuring that in the end God’s kingdom is victorious. In spite of the disagreements in interpretation, the outcome is sure: evil “will meet his end” (11:45). The conflicts between the kingdom of God and that of this world will continue, but in the end the Lord will establish his glorious kingdom. [Apocalyptic Literature]

11. TROUBLES AND VICTORY (12:1–13)

12:1–4. The victory will not come without persecution and perseverance (12:1). These words encourage the godly in any age to await the kingdom of God. The saints are promised life everlasting and joy, whereas the ungodly will experience everlasting disgrace (12:2–3). All who die will be raised to life, but not all who are raised in the body will enjoy lives of everlasting bliss—only those whose names are recorded in the book of life. The godly respond to God and will be accounted to have insight and to be wise; they will lead others to life, wisdom, and righteous living. Their future will be glorious, as they will share in the victory of the Lord.

The visions are to be closed, so that the wise might read them and gain understanding (12:4). Revelation of the future is for encouragement and the development of hope, faith, and love, rather than for speculation. The godly will always find comfort in the revelation made to Daniel.

12:5–10. Daniel receives assurance that these visions are true and will come to pass. He sees two witnesses on opposite banks of the river (12:5). In between the two is the angelic messenger, “the man dressed in linen,” who is above the river (12:6). He swears by the Lord’s name that the fulfillment will take place “for a time, times, and half a time” (12:7; cf. 7:25). Concerned about what he has heard, Daniel asks about the outcome (12:8). He does not receive much of an answer, but the angelic messenger does assure him that through the process of perseverance the Lord will always have a faithful remnant (12:9–10). This remnant will endure the process during which they “will be purified.” The wicked, however, will persevere in their evil. They will never come to understand their folly but will be cast out of the kingdom.

Daniel 12:2 is one of the few texts in the OT that speaks clearly of the resurrection from the dead. The NT, however, will expand on this theme, placing it at the center of the Christian hope regarding the future.

12:11–13. The calculation of the end is enigmatic. The Lord reveals to Daniel visions of the progression of redemption until the final and victorious establishment of his kingdom. These words are to encourage godliness in the face of evil. Though the oppression and persecution may be longer (1,335 days) than the tyranny of Antiochus Epiphanes (1,290 days), blessed is everyone who perseveres to the end.