When a gemsbok, a large African antelope, was shot, the partly decomposed body of a leopard was impaled on its long horns. Tigers are often gored by water buffalo and gaur. Porcupine quills also take their toll on inexperienced cats. At 15 kilograms, these large, slow-moving rodents can provide a sizable meal. However, many leopards and tigers that turn to man-eating have been previously debilitated by porcupine quills; pumas have also been found with porcupine quills in their face. These cats eventually learn to flip porcupines over onto their back before they kill them, but even then, quills are routinely found in their scats in some areas.

Servals often hunt small rodents they can hear but not see. They rush toward the prey, then grab and chomp down on it with their teeth. This is a safe and effective way for cats to dispatch small prey.

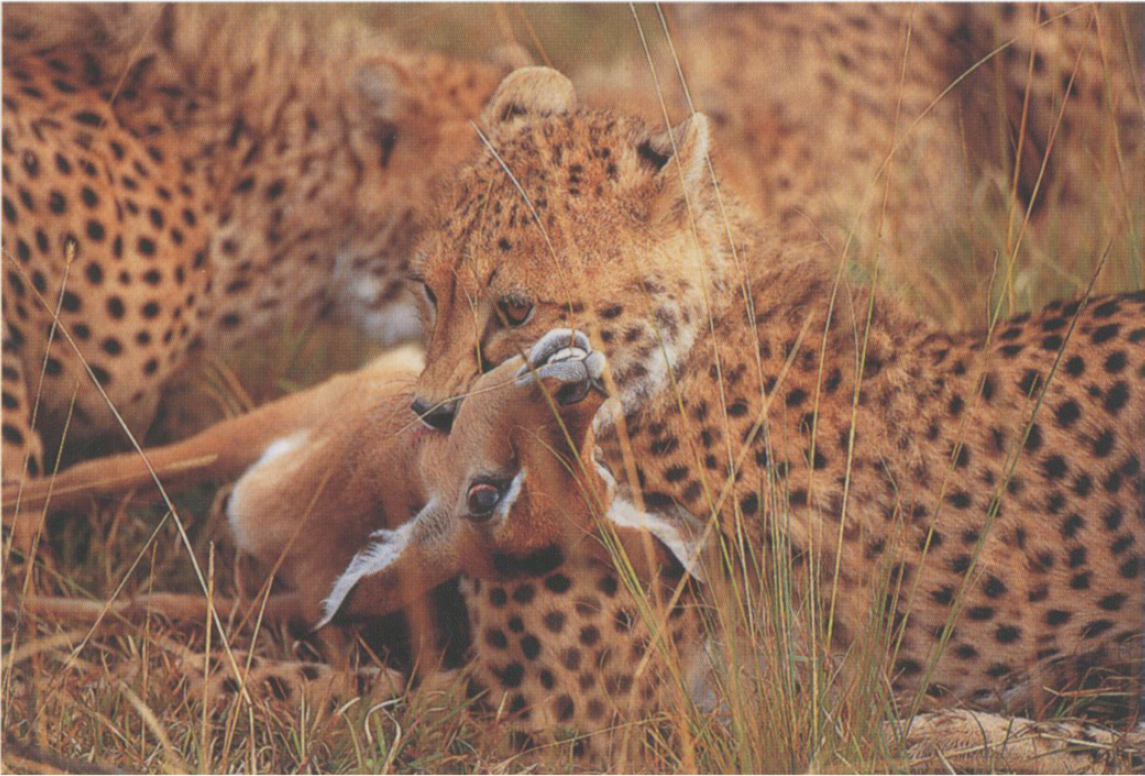

Cheetahs kill large prey by holding the victim’s throat between their teeth until the animal suffocates. This same technique is used by other cats, including tigers, snow leopards, Eurasian lynx, and caracals, when they are attacking prey much larger than they are.

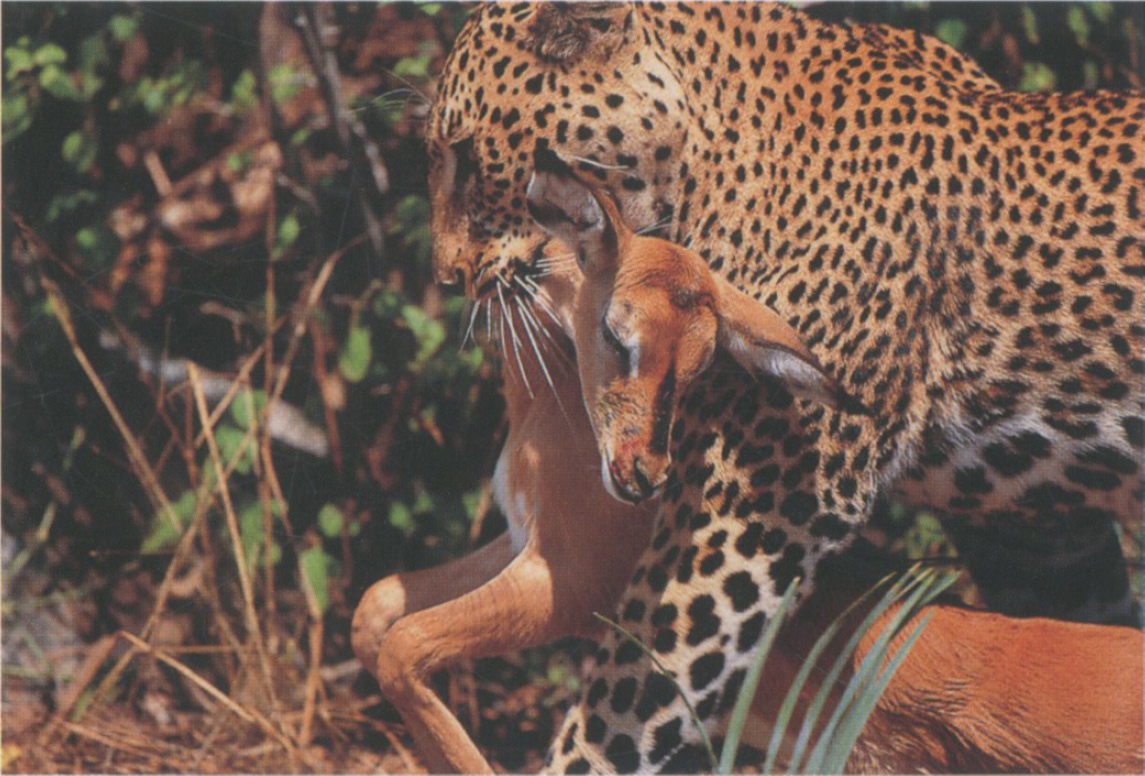

This leopard has killed an impala with a bite to its nape. The cat’s canines either crush a prey animal’s cervical vertebrae or sever its spinal column. The killing nape bite is employed by all cats, but this killing technique is the most difficult for a young cat to master.

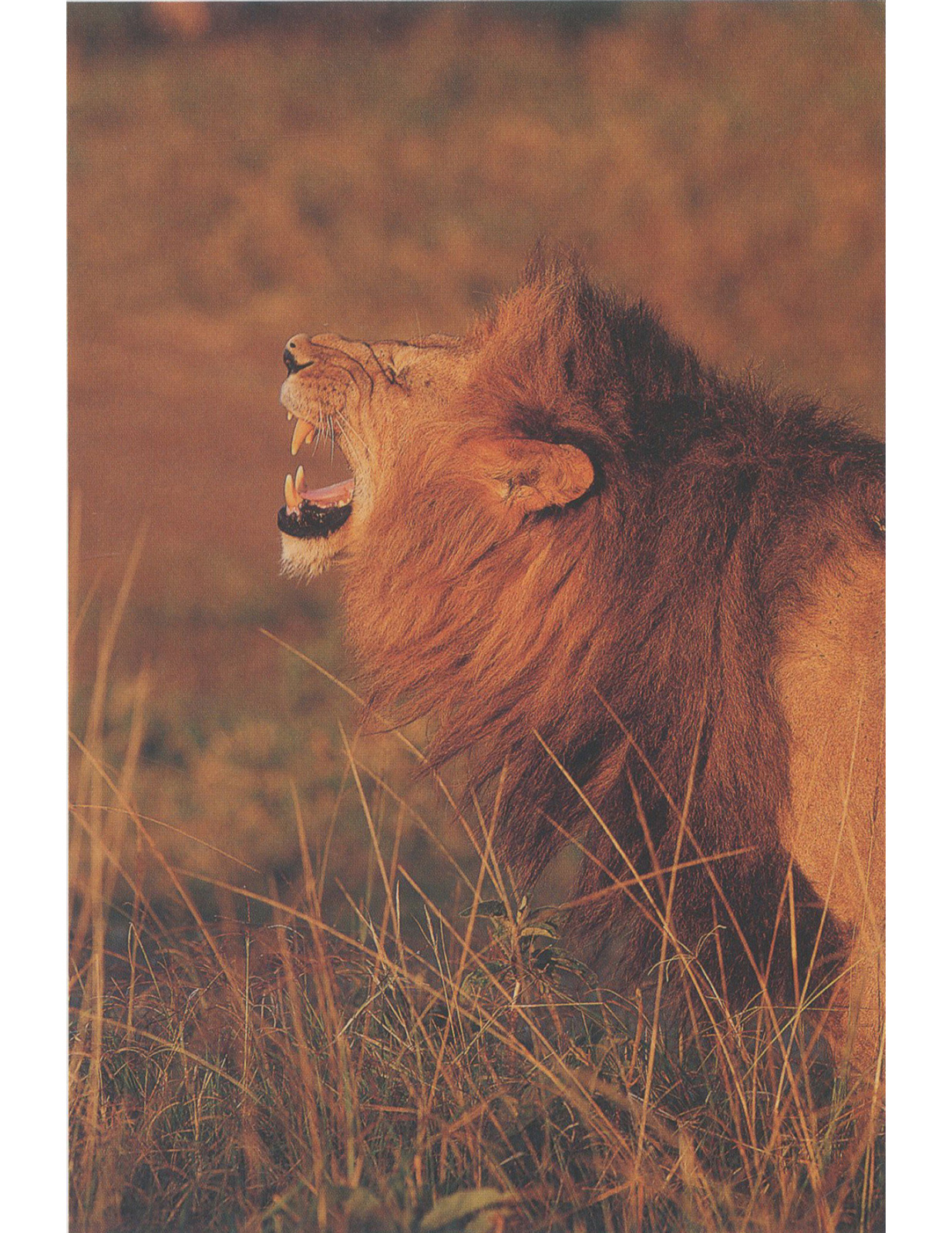

Lions risk lethal injury from the flying hooves of wildebeests and other ungulate prey. Hunting large animals is dangerous, and cats are often hurt by swift kicks or goring antlers and horns. Even small prey can inflict debilitating wounds. Leopards and tigers sometimes end up with face full of porcupine quills when they try to kill this spiny rodent.

From time to time we hear reports of a puma or leopard killing many prey animals within an enclosure, usually livestock such as sheep or goats, and then eating only one, if any, before the cat is driven off. This is greatly upsetting to the livestock owner, and, if possible, the cat is hunted down and killed. This “surplus killing” makes little biological sense: it has little survival value, and it even seems to be a waste of effort on the predator’s part. A prudent predator should use its food resources efficiently.

Why kill more than can be eaten? Generally in mammals, a feedback mechanism prevents further eating once an animal is full. Cats show very little activity after a substantial meal and may not hunt for hours or even days, depending on the species. If a cat finds itself in close quarters, inside a livestock holding area, for example, with many potential prey animals, the search and detection part of its hunting behaviors is no longer necessary, and somehow the seizing and killing parts click into a loop without any controlling feedback through consumption and satiation. In this situation, killing does not necessarily lead to eating; instead, the predator does some more killing. This behavior is adaptive to this particular situation, because normally if a cat is able to kill several prey quickly, it will do so and eat the carcasses later. But, outside a livestock pen, this is rarely possible.

On average, big cats consume 34 to 43 grams per day per kilogram of their weight. Puma-sized cats consume about 56 grams per day per kilogram, and ocelot-sized cats consume 60 to 90 grams per day per kilogram. The very small cats (less that 2 kilograms) consume 125 to 150 grams per day per kilogram of their weight. Yes, smaller cats must eat proportionally much more than larger cats. On the basis of per gram of cat, the metabolic rate of a black-footed cat or other very small cats is much greater than the metabolic rate of a tiger; thus, the black-footed cat needs relatively more fuel to stay alive (see What Does Size Have to Do with It?).

How does this translate into killing frequency? In the dry South African shrub, Sliwa (1974) found that black-footed cats killed a bird or mammal every 50 minutes, on average. Geertsema (1985) observed servals in Tanzania’s Ngorongoro Crater capturing 5,700 to 6,100 prey per year, equal to about 3,950 rodents, 260 snakes, and 130 birds. In Doñana National Park, a single Iberian lynx killed about one rabbit a day; a female of this species with two kittens needed to kill three rabbits a day (Delibes et al. 2000). A Canada lynx was found to kill about one hare every 2 days, for 153 hares per lynx per year (Nellis and Keith 1968). The distance traveled per kill depended on the number of hares taken. Lynx killed about the same number of hares whether hare numbers were low or high but had to travel farther each night to do so when the numbers were low (Okarma et al. 1997). Subadult and female Eurasian lynx without kittens in Poland’s Białowieza forest killed 43 red deer or roe deer per year, and adult males killed 76. In Wyoming, Anderson and Lindzey (2003) observed pumas to kill on average a large mammal every 7 days, but this ranged from 5.4 days per kill for a family to 9.5 days for a single subadult, for an average annual total of 52 large mammals, which included mule and white-tailed deer, elk, pronghorn antelope, moose, coyote, and livestock.

John tracked a female tiger with two 6-month-old cubs living in Nepal’s Royal Chitwan National Park, where preferred tiger prey, such as wild pigs and sambar, are abundant. This female killed every 5 to 6 days, which amounts to 60 to 70 kills per year (Seidensticker 1976). Further studies in Chitwan have revealed that, on average, female tigers make a kill once every 8 to 8.5 days, or roughly 40 to 50 kills a year. Studies of lions suggest a slightly lower average. At an estimated average requirement of 5 kilograms of meat per day to stay alive, each lion will account for about 30 medium-sized kills per year.

Scientists refer to animals’ food-storage behavior as caching. Many cats cache the remains of kills that provide more food than they can eat at one time, but it may be a challenge for a cat to keep scavengers from stealing the meal. Spoilage may also be a problem, especially in hot weather, whereas a carcass may freeze in cold weather and be preserved. Pumas drag a large kill to a secluded site, bury the carcass with snow, leaves, grass, dirt, or other debris, and stay nearby until the meat is finished, usually after about three nights. Pumas drape themselves over a frozen carcass to defrost the meat. Most cats cache their leftovers but do not necessarily guard them. Both tigers and pumas may travel to a resting site several kilometers from the cache and then return. When a tiger returns to its meal, it does so with caution and stealth: if a pig or a brown bear is scavenging the kill, the tiger has a chance to kill another big meal. The habit of returning to an unguarded kill, however, leaves tigers vulnerable to a bigger threat than losing dinner: people intent on killing tigers lace cached carcasses with poison.

When many scavengers are present, leopards drag a large kill up into a tree, draping the body over a limb. This keeps thieves (more formally referred to as kleptoparasites) such as lions, spotted hyenas, and ground-feeding vultures at bay. However, this kind of caching also has its risks. In a Namibian study, leopards had potentially dangerous interactions with other carnivores at 12 percent of their kills. Leopards dragged all carcasses, except hares and birds, on average 140 meters into thick underbrush, where they then fed; they dragged their kills into trees only 3 percent of the time. A kill in a tree alerted lions, and the lions then pursued and tried to kill the leopards. Where cover is scarce, such as in the Kalahari Desert of southern Africa, leopards dragged prey as far as 700 meters.

In contrast, cheetahs do not cache food or return to carcasses. Unable to fend off the large scavengers of the African plains, cheetahs are often driven off their kills before they are finished eating, so they just have to hunt again.

Smaller cats cache uneaten prey too. Black-footed cats regularly cache prey, ranging from insects and birds to shrews, rodents, hares, and scavenged antelope fawns, by covering it with soil and grass. Frequently, these cats leave carcass parts sticking out, which might help them find the spot again when they return within a few hours. In the Białowieza Primeval Forest in Poland, Eurasian lynx were often found to move the carcasses of their ungulate kills to dense vegetation or push them under fallen logs, where they covered them with soil, leaves, moss, deer hair, or snow to protect them from scavengers so that they could feed on the cached prey for several days. Roe deer were dragged farther than the heavier red deer, but both usually less than 100 meters. In this study, 80 percent of the cached lynx kills were subsequently fed upon by scavengers, most often wild pigs.

To avoid scavengers, most cats drag or carry their prey to sheltered places to eat and cover the remains of an unfinished kill to preserve it for another meal. Leopards sometimes haul large prey like this warthog up into a tree, out of the reach of nonclimbing lions and hyenas.

The dynamics of the relationship between predator and prey vary considerably from ecosystem to ecosystem. Biologists call it a top-down process when predators influence the number of prey; when prey influence the number of predators it is called a bottom-up process.

As a rule of thumb (although with some variation), about 10 percent of the sun’s energy is fixed into green plants through photosynthesis, about 10 percent of that energy passes to herbivores, and about 10 percent of the herbivore energy is available to carnivores. The primary productivity, or amount of plant growth, in an ecosystem is influenced by its amount of light, warmth, moisture, and nutrients, all of which differ considerably from place to place and over the seasons. This bottom-up effect determines the amount of plant food that is available to the herbivores, its primary consumers, in a particular place and time. The number of herbivores is limited by the quality of the plant food, the form it is in, and the defenses the plants have evolved to keep from being eaten. For example, tropical rain forests are some of the most productive places on Earth, but most of the plant material is in the form of tree trunks, which most herbivores can’t eat; the plant material in leaves is out of reach to terrestrial herbivores. Also, leaves deploy defenses, such as toxic or noxious secondary compounds, to protect them from being totally eaten by insects. These same compounds reduce the quality of the leaves as food for arboreal herbivores, such as primates and sloths. The actual amount of plant growth that is digestible and available determines how many herbivores can live in a place, and this, in turn, determines the number of predators, or secondary consumers, that can live there. The plants are subjected to top-down forces when the herbivores eat them; herbivores are subjected to these same forces when the carnivores eat them.

Some ecologists argue that predators regulate the number of herbivores, which in turn limits the damage herbivores do to vegetation. Other ecologists argue that the bottom-up forces are most important in determining how ecosystems work. Most conservation biologists agree that both top-down and bottom-up forces are important in most ecosystems. Over the last 75 years, biologists have addressed this question in countless studies, most of which have focused on the impact of the predator on its prey, many fewer on the effect of prey on their predators.

In many ecosystems, the density of wild cats is positively correlated with the density of their primary prey. More snow leopards occur where there are more blue sheep. More lions occur in areas where prey numbers are highest year around. Cheetah and leopard densities are strongly correlated with “lean-season prey biomass”—the combined weight of all potential prey available when food for prey is least abundant. Going a step further, biologists Chris Carbone and John Gittleman found that, across the whole range of carnivore sizes from mongooses to polar bears, about 10,000 kilograms of available prey biomass are required to support 90 kilograms of any given species of carnivore. This means that 10,000 kilograms of prey biomass are required for every 0.5 tiger, 2 leopards, or 45 rusty-spotted cats. Ultimately, however, predator populations are constrained by the reproductive rates of their prey rather than by the amount of prey present at any one time (see What Does Size Have to Do with It?).

Carnivore populations adjust to prevailing food supplies through changes in reproductive output, survival of offspring, and dispersal of young away from their natal areas. A study in Canada showed that as snowshoe hares declined, lynx body fat declined and the initial reproduction of female lynx occurred at a later age, pregnancy rates declined, and kittens were less likely to survive. A study in Tanzania demonstrated that the survival of lion cubs is also directly related to lean-season biomass of prey; cubs’ survival rates during their first year of life were more than twice as high where prey numbers were high.

Adult mortality also increases when food is short. Cats often starve, and hunger also leads cats into conflict with people. During very hard winters in the Russian Far East, when deer and wild pigs starve and die, tiger-human conflicts increase, as they do wherever hunters have killed most of the tiger’s prey. Food shortages also lead to more strife among individuals of a species because they trespass into one another’s territories looking for food. Moreover, the size of territories is influenced by the amount of food available.

When the rabbit and hare populations declined in the shrub-covered, semidesert of Idaho, the size of bobcat home ranges increased fivefold; that of lynx increased threefold during a snowshoe hare decline in the Yukon. Lynx also become nomadic, disperse farther, and travel farther each day when hare numbers are low. In Africa, the size of the home areas of lion prides is correlated with lean-season prey availability. During periods of prey scarcity, the number of transient or dispersing lions increases, something also seen in feral domestic cats. Dispersing individuals normally do not reproduce and have higher rates of mortality than nondispersing individuals have.

Understanding cause and effect in the predator-prey relationship is challenging, both because secretive wild cats are very difficult to count accurately and because defining what is prey for a cat can be difficult. In his study of pumas, John found that numerous deer and elk resided within the home areas of pumas, but only those prey adjacent to adequate stalking habitat were available to the cats (Seidensticker et al. 1973). Pronghorn antelope normally live in the open plains and shrub steppes of the American West, where adults, with their exquisite eyesight and great speed, are nearly immune to predation. But when pronghorns enter rugged, bushy terrain in central Arizona, they become vulnerable to pumas, and puma predation on female pronghorns has been high enough to decrease the size of the population.

Cats may also take prey species that have become newly available to them. Biologists Joel Berger and J. D. Wehausen (1991) described a great example. Pumas were historically absent from the Great Basin Desert of Nevada, but when livestock grazing changed the vegetation from grass to shrubs, the number of shrub-eating mule deer increased. Pumas followed the mule deer. Until then, the bighorn sheep living there had experienced little predation, but with the arrival of the pumas they were decimated. Similarly in the Sierra Nevada, after pumas arrived, their numbers had to be controlled to protect a remnant endangered population of bighorn sheep. Studies of introduced species, specifically feral cats introduced to islands, offer abundant evidence of the profound effect a predator can have on “naive,” vulnerable prey. Island breeding seabirds are particularly vulnerable to predation, because they lack any behavioral or morphological defenses against it (see Why Are Feral Cats—and Pet Cats—Sometimes a Menace?).

When several predator species coexist in an area, competition complicates the predator-prey relationship, or at least our understanding of it. Tigers and leopards seem to depress sambar and Indian muntjac numbers in India’s Nagarohole National Park. But in comparing Nagarohole with other Asian tropical forests, John and his colleagues Charles McDougal, Ullas Karanth, and Mel Sunquist found that the occurrence and relative densities of tigers and leopards depended largely on the relative densities of different size-classes of prey (Seidensticker and McDougal 1993; Karanth and Sundquist 2000). Leopards are more abundant where medium-sized prey are abundant for them and where large prey are abundant for tigers. Where medium-sized prey are few, tigers exclude leopards, because leopards can’t get at the large prey. But where neither large nor medium-sized prey are abundant, leopards do better than tigers, because leopards can supplement their diet with prey too small for a tiger to survive on.

Ecologists Charles Krebs, Tony Sinclair, and associates found that predators control prey populations when predators have a direct density-dependent effect, which they often do (Krebs et al. 1995). Density dependence is the correlation between prey density and predator-caused mortality, measured as a percentage of the prey populations. When prey populations are low—“in the pit,” as ecologists say—predators can affect their numbers; but if something happens to reduce predator numbers, prey can break out of the pit. This leads to prey “swamping” predators: prey are so numerous that the size of their populations is unaffected by predators taking their requisite share. This phenomenon has been seen in many prey-predator systems. For example, even the combined predation of cheetahs, lions, wild dogs, and spotted hyenas has little effect on the migratory herds of ungulates in the Serengeti. In this system, the large ungulates are regulated by their food supply, not by predators.

In synchrony across Canada, snowshoe hares exhibit 8- to 11-year population fluctuations, during which their numbers vary 10- to 25-fold. Is it lynx predation or food availability for hares that drives this cycle? Is it bottom-up or top-down? Lynx take more hares when the prey are abundant, and the number of lynx fluctuates 2- to 10-fold during the hare cycles. Biologists once thought that plant food shortages occurring when hare numbers were greatest set the decline in motion, because the hares began to starve, having eaten themselves out of house and home. But subsequently their predators caused even higher hare mortality rates, until hare numbers became so low that lynx began to starve and die, giving the hares a chance to rebound. Extensive experimental work has failed, however, to demonstrate that food shortages initiate the decline and has showed instead that the cycle is most likely due to interactions of all three factors—food plants, hares, and predators—throughout the cycle.

Recently biologists Ricardo Moreno and Jacalyn Giacalone set out to determine the impact of ocelots on Barro Colorado Island, a tropical rain forest island in Panama managed by the Smithsonian Institution as a research station (Leigh 2002). Scat analyses revealed that an ocelot’s annual take was 22 two-toed sloths, 18 three-toed sloths, 15 white-faced monkeys, and 18 agoutis (medium-sized rodents). A 10-kilogram ocelot eats about 33 times its own weight a year; therefore, as much as 10 metric tons of mammal prey a year were eaten by the 30 or more ocelots living on the island. The entire island is thought to support 68 metric tons of mammals.

In studying tropical forest islands of various sizes that were created when a river was dammed in Venezuela, ecologist John Terborgh and his associates found that where predators of vertebrates were absent, the densities of rodents, howler monkeys, iguanas, and leaf-cutter ants were 10 to 100 times greater than on the nearby mainland, where mammalian predators, including ocelots and as many as four other species of cats, were present (Terborgh et al. 2001). This strongly suggests that predators regulate these prey populations. Further, without predators to control the herbivores on these islands, the densities of seedlings and saplings of canopy trees were severely reduced. These biologists concluded that predation pressure on herbivores “has been weak over much of the earth since the eradication of megafauna by stone age hunters, so bottom-up regulation has become widespread, creating aberrations that have spawned the top-down versus bottom-up controversy” (p. 1926).

Most carnivores live solitarily, and most wild cats are no exception. This style of living suggests that, among carnivores, conditions rarely favor group living outside the reproductive period. In other words, the costs of group living outweigh the benefits. Group living carries several disadvantages: it increases the chance of being detected by a predator or competitor; it increases the risk of disease and parasite transmission; and it increases the chances of aggression and injury, which a solitary-hunting felid can ill afford. So living at low densities is characteristic of species at the top of the trophic pyramid, or food chain. Being obligate carnivores predisposes most cats to living alone.

Only 10 to 15 percent of all the carnivore species live in groups outside the breeding season. Among the cats, feral domestic cats live in groups around very rich resource bases, such as docks, dumps, and farm sites, but live solitarily when their food resources are less abundant and well dispersed. Cats don’t even live in mated pairs, which is the basic social unit in canids.

In the pair-forming canids, the males provision the females and the young by bringing food back to the den; they either carry it back in their mouth or they regurgitate food they have eaten. Cats do not have the capacity to bolt down large chunks of meat or eat prey whole, nor do cats seem to have the capacity to greatly distend their stomachs, as wolves do, for example. Cats slice up their prey carefully with their carnassials. When they kill larger animals, they conceal them by thick cover. A prey item that cannot be eaten in a single meal is cached, and the cat returns for several meals. John radio-tracked a female leopard in Nepal that stayed away from her cubs for days at a time while she hunted for sambar deer, killed one, and consumed it, one meal at a time, until it was finished. She spent her time guarding her prey rather than returning to her 6-week-old young, which she had stashed in a stand of tall thick grass no more than an hour’s travel time away.

Most cats live alone, probably because most hunt more efficiently as individuals. With the exception of cheetahs and lions, cats stalk and ambush prey alone. Even in situations where large prey are abundant, as occurs in some habitats of tigers, lynx, pumas, and jaguars, these species do not form groups to take advantage of some of the potential benefits of sociality. Perhaps their prey is just too difficult to catch and kill in the thick cover where they hunt. Unlike cats, canids cannot bring down a large prey animal alone without great difficulty, and their chasing style of hunting lends itself to cooperation, as we see in wolves. Also, most of the smaller canids are not strictly meat-eaters, supplementing their diets with fruits and vegetable matter, which may allow them to forage and feed communally, something not seen in the cats.

With the exception of lions and free-ranging domestic cats, cats seem to be generally intolerant of conspecifics (members of the same species). This leads to females living spaced apart in home ranges, which may either overlap to some degree or be mutually exclusive of one another in what are referred to as territories. Generally, biologists have thought that the young, upon reaching nearly adult size, either leave their mother’s home range on their own, or are abandoned, or are even sometimes ousted by their mother from her territory. However, we are learning that in many cat species, even though young males leave their mother’s territory, not all female offspring do. If the mother’s territory has proven to be adequate to support her and her family and even more resources have become available with the departure of young males, a young female will take over part of her mother’s area rather than leave it, thus narrowing the mother’s original range. This may happen with several different female offspring until, eventually, the mother finds that she cannot survive in the small area remaining, and she abandons it. In effect, she is squeezed out by her daughters or, in some cases, her granddaughters, and this marks the end of her reproductive life.

Except in lions and free-ranging domestic cats, though, female cats and their female young don’t stick together. We do not know if artificial selection during domestication led to greater tolerance among domestic cats, but it has never been naturally selected for in wild cats. Intolerance toward other cats of the same species is hard-wired, so that most wild cats cannot live in groups even if the resources are sufficient to support it. So far, only group-living domestics have been studied in resource-rich urban environments. But recent studies of fishing cats and other wild cats living around resource-rich Asian cities and towns will help to answer this question.

Barely visible in the grass, this leopard exemplifies the secretive, solitary lives of most cats. A mother and her young are the largest group formed by all species except lions, cheetahs, and some feral domestic cats. Once they leave their families, males spend the rest of their lives alone, only occasionally meeting a female to mate.

Among lions, both males and females live in groups; these coalitions of males and prides of lionesses live where food is abundant in the form of ungulates. Also the presence of many other lions is important for reproductive opportunities. Male lion coalitions are more successful in gaining breeding access to pride-living females by working as a unit to defend a pride when they are resident or to oust the current resident males; some very successful male lion coalitions gain access to more than one pride of females by displacing additional males. Female lions can live in groups because of their hunting style: related females hunt cooperatively to take large prey in open habitats. Large carcasses last a long time and are hard to defend, so it is easier and genetically beneficial to share with a relative rather than lose food to unrelated lions. The further advantage of group living in female lions is that they can join together to defend their cubs against infanticidal males.

Male cheetahs also live socially, in coalitions of two or several males. As a unit, these males are more successful in holding down large territories containing important resources that are attractive to breeding females, such as food and den sites. Female cheetahs, on the other hand, live and raise their young alone. As soon as the young are mobile, they and their mother begin to follow herds of migrating ungulates, leaving the males and their territories behind.

So in lions and in cheetahs, high densities and localized females create intense competition among males but favor the formation of their alliances (often involving related males), which can win in battles against single males or smaller coalitions. Living in groups also allows more complex social behavior to evolve, such as cooperative hunting, joint maternal care, organized vigilance, and protection from intruding conspecifics.

With no pair bonds among felids and no direct contribution among males to the care of their offspring, how do males improve their reproductive success? They can do so by mating with more than one female. Males attempt to include as many females as possible within their territories. Ultimately, however, males too are restricted by their energy needs and by the amount of space they can actively and effectively defend. The resulting spatial pattern results in what biologists call intrasexual territoriality. Female cats are contractionists, and males are expansionists. A female contracts the space she uses to include just the area that contains the resources needed for herself and her offspring. Males expand the space they use to the extent possible while maintaining the ability to defend it, thereby retaining exclusive breeding access to all the females living within.

John studied pumas’ use of space in different seasons and habitats (Seidensticker et al. 1973). He found that male territories are always significantly larger than those of females and their young living in the same general areas as the males. Pumas have young during all seasons of the year, so there is never a nonbreeding season. In pumas and in other cats, males kill the young of a female they do not know, so that she enters estrus again and he can sire his own offspring with her. This is a strong reason for males to maintain their territories year around to prevent the intrusion of other adult breeding males.

Sometimes both males and females make forays outside their usual territories, males to gain access to other females, females to mate with males living farther away. These can be very dangerous excursions because of the risks of encountering a resident territorial cat. However, there are also advantages. Both male and female cats are known to change territories if an adjacent, better territory becomes open through the death of the resident. Females are much more conservative than males in shifting home ranges, because they know their areas and where and when they can predictably find the prey they need to kill to support their litters. By moving, they lose this advantage, at least in the short term. Males are on the lookout for the area richest in females that they can defend with the least effort and danger from other males.

A home range or home area is the space an animal uses that contains all the resources it needs to survive, including food and water, shelter from the elements as well as places to sleep and hide from predators, mates, and places to rear young. Cats also make occasional forays outside the area they usually cover in order to check out developments in the social and physical neighborhood. The knowledge a cat gains in doing this may be essential to its survival or to improving its reproduction potential, even though these forays are not included when we calculate the size of the cat’s home range.

Home areas may overlap among individuals. If there is no overlap, the home range is called a territory; a territory is occupied more or less exclusively by a single individual or a group, as in a pride of lions, and is maintained by means of repulsion through overt defense or advertisement. Usually, males defend their territories from other males, and females defend theirs from other females. Among cat species, home ranges are most often territories. A home range of either type provides advantages: residents know from experience where and when to find the resources they need to survive, where potential mates can be found, and where the special places they need to rear young are located. Newly independent young cats as well as old cats that have been displaced from their territories may wander through the territories of established residents, which puts them at risk of attack. Or these displaced individuals may live in very marginal habitats, where they await their chance to take a resident’s place, either through the death of the resident or through combat.

Cats, like most carnivores, respond to fluctuating resource supplies in different ways. Where the primary prey migrate between distant summer and winter areas, a cat either moves from one part of its territory to another to follow the food, or it expands and contracts its use of the territory to encompass the expanding and contracting range of the prey. This is a flexible strategy. In tropical environments, where resources are more constant and equally distributed throughout the year, cats tend to use their entire territory year around. If the resource base varies from season to season and from year to year in the same areas, the cat has two options: adjust the territory size to the resource base needed to support itself (the flexible strategy) or set territorial boundaries at an invariant, usually large, size that fills the cat’s needs at all times (what Torbjorn von Schantz [1984] calls the obstinate strategy).

Similarly, just as female cats tend to be contractionists and males expansionists, some entire species are contractionists, occupying the smallest economically defensible territory possible. Others species are expansionists, having territories with resources well in excess of minimal requirements for survival. Cats use both of these strategies, depending on the species and the environment.

Compare, for example, the size of tiger territory in the prey-rich tropical riparian forest and tall grass floodplains in Nepal with that of tigers living in the prey-poor temperate, oak-pine forests of the Russian Far East. In Nepal, the tiger’s prey doesn’t move seasonally, although the densities of prey vary from one habitat type to another. In Russia, the pigs and deer, the mainstay of the tiger’s diet, shift between winter and summer ranges. In Nepal, female territories were found to be 16 to 20 square kilometers, and those of males were 60 to 72 square kilometers. In Russia, females used areas that ranged in size from 245 to 415 square kilometers in summer; winter areas were smaller and overlapped in varying degrees with the summer-use areas.

In California, female puma home range sizes in the northern Coast Range have been found to average 90 square kilometers in summer and 100 square kilometers in winter; males’ average 300 square kilometers in summer and 350 square kilometers in winter. In the dry Sierra Nevada, where the puma’s prey, mule deer, shift between winter and summer ranges, puma home range size for females and males, respectively, is 541 and 723 square kilometers in summer and 349 and 469 square kilometers in winter.

Cats regularly patrol the boundaries of their large territories to fend off intruders of the same sex looking for territories of their own. With territories ranging from about 20 square kilometers to nearly 300, depending on the habitat and the sex of the animal, tigers must cover a lot of ground to defend their home turf.

In contrast, the home range of the tiny kodkod averaged 2.69 square kilometers in one southern Chile site. At another site, where the biologists studied kodkod movements in both forest and farm land, males ranged over 0.7 to 17.4 square kilometers and females over 0.6 to 1.46 square kilometers.

Cheetahs living in the Serengeti exhibit huge differences in territory and range size between the sexes. Male coalitions hold territories with dens and nonmigratory prey, which attract females raising young until the young are old enough to follow migratory ungulate herds. Female cheetahs do not defend their home ranges and thus are not considered territorial. The average size of a female home range was found to be 833 square kilometers, and that of male territories was 37.4 square kilometers.

In general, larger mammals usually have larger home range sizes. Strict carnivores, such as the cats, have larger home ranges than similar-sized omnivores and herbivores. However, home range sizes vary among the cat species, among individuals of the same species and the same sex occupying different areas, and between the sexes within the same species, as our examples above demonstrate. The variables that affect home range size include habitat preference of the cat, habitat preferences of the prey, prey density, prey distribution in the area, and competition among carnivore species and among members of the same cat species.

In a study in California that compared 57 individual home ranges of pumas, sex, body mass, relative deer abundance (their primary prey), and season all influenced home range size, although not in a linear way. For instance, males always had larger home ranges than females, even when the two sexes were about the same size. The home ranges of young adults were larger than those of older adults. Surprisingly, deer abundance was a weak indicator of home range size, which was also true of the reproductive status of a female and body size in either sex. Other factors thought to influence home range size included the density of other pumas in the area, the densities of alternative prey species, and the density of roads and human developments.

Where John studied pumas in Idaho, the size of home areas also was not directly related to the density of their primary prey in winter, mule deer and elk. Of course, a puma’s home area had to support enough deer and elk for the cat to survive, but beyond that parameter home area size was set by topographic conditions. The most important element was abundant places where these cats could successfully stalk and kill their prey. Home ranges of both males and females were smallest where the canyons were very rugged and broken. Where the canyons turned into basins with large treeless areas, puma home areas were larger. In both types of habitat, 45-kilogram female pumas were killing 360-kilogram male elk, so the pumas had to use every possible terrain advantage they could.

Cats generally live and hunt alone but spend their lives embedded in dynamic societies. These societies include their neighbors, their mates, offspring, and parents, as well as strangers that enter the scene from time to time. Solitary-living females (such as tigers) may interact face to face and share their range with one litter of young (male and female) at a time, whereas group-living females (lions) may share their range with their female young from several litters and continue to do so when those female offspring are adults.

Cats are not truly asocial; it’s just that many of their social interactions are conducted through long-distance communication, with loud vocalizations and scent marking (see What Is Scent Marking?). At the same time, they have a rich repertoire of short-range communication behaviors, including purring in many species, vocalizations of friendly greetings, and cheek rubbing between courting males and females, as well as facial expressions and body postures that are often seen in aggressive encounters.

An aggressive cat on the offensive growls and rotates its ears forward, stands with its back parallel to the ground or with its weight shifted to its front legs, and lashes its tail from side to side. At the other extreme, a submissive or defensive cat hisses, bares its teeth, flattens its ears, and may slink away, crouch down, or even roll over onto its back. When a cat responds to aggression with submissive behavior, it is essentially “crying uncle.” By giving up to a clearly stronger opponent, the cat can live to fight another day.

All cats leave scent marks in the environment; these reveal information about an individual’s sex, reproductive status, identity, occupation of a particular area, and perhaps its age, dominance, and health status. Rates of scent marking are highest at territorial boundaries, when these boundaries shift or when the entire territory changes in possession, and when females are approaching estrus. The odorous substances involved in this marking are in the urine, feces, and saliva, and are also produced by special glands on the tail, chin, lips, cheeks, and feet. Scent marking also has a highly visual and spatial component. Marks are not deposited at random. Instead, marking is most frequent at boundaries between territories, along well-used paths, at intersections of paths, and on particularly prominent habitat features, such as a large, conspicuous tree that stands a bit apart from others. Tigers are even selective about the species of tree on which they spray.

To draw even more attention to spots that have been scent-marked, cats rake their claws across the bark of trees, leaving visible scars as well as odors from the glands on their paws. Many cats scrape the ground with their hind feet, leaving a bare patch to highlight a spot on which they’ve urinated. Some cats deposit feces on scrapes, either accompanied by urine or alone. Ocelots, bobcats, and other wild cats repeatedly defecate in the same “toilet” spot to create a highly visible, smelly mound. Sand cats, which live in deserts with little or no vegetation, create piles of feces on heaps of sand. Geoffroy’s cats are unusual in depositing their feces in the crooks of tree branches as high as 3 to 5 meters above the ground, a surprising behavior for a cat that spends most of its time on the ground.

Pumas do not spray, but males make carefully placed scrapes. In his study of pumas, John found that scrapes were 15 to 46 centimeters long, 15 to 30 centimeters wide, and 3 to 5 centimeters deep (Seidensticker et al. 1973). Most were placed from 0.3 to 2 meters from a fir or pine tree or from a rock face or overhang. On slopes, scrapes were always made on the downhill side of trees. Scrapes were rarely located on trails; usually they were off to the side. He found scrapes near the mouths of canyons, in draws, and on ridges, and they appeared to be located where the lay of the land indicated easy passage.

Solitary cats communicate by leaving smelly messages on objects in their environment. Other cats read the messages to find out about the animals that left them, learning their sex, reproductive status, and how recently they have been in the neighborhood. This bobcat is leaving such a message by rubbing its cheek gland, which produces an odorous secretion, across a fallen tree.

Cats want others to find their scent messages—communicating at a distance is safer than potentially dangerous face-to-face encounters. As many cats do, this ocelot is raking its claws along a tree trunk, leaving deep, highly visible gouges as well as scent from glands on its paws. This makes it easy for other ocelots to find the message.

These visual and spatial signals of scent marking help to ensure that the marks are not missed by their intended audiences. Both male and female territory holders, for instance, prefer to avoid the risks of a fight with a transient and thus want the transient to find and be deterred by marks that delineate the boundaries of their territory. Similarly, a female approaching estrus wants to advertise her status so that potential mates will seek her out, and before mating, a male may also increase his rates of marking. A male black-footed cat sprayed 585 times on the night before mating, whereas the more usual rate for a resident male is 10 to 12 times an hour during active times of the day.

Scent marks, unlike vocal or visual signals, persist in time and thus are uniquely suited to communicating about the past. A fresh scent mark reveals that it was laid down very recently and the cat that made it is very likely nearby. An old, faded mark says the opposite. Thus a transient male, for instance, may be undeterred from entering another male’s area if the marks are old. Cats may also make occasional forays into the territories of others and leave scent marks, as if to test the competition. This means that scent marking is an important job and must be performed repeatedly and frequently. A few studies suggest that scent marks persist for 3 to 4 weeks before they are ignored as signals of ownership.

Cats also overmark. A male that comes across the scent mark of another will mark over it, in a sort of game of one-upmanship. Cats occupying adjacent territories concentrate their marks at the borders, keeping others informed that they are still in residence.

Cats criss-cross their territories regularly both to keep track of what’s going on in their area by reading the smelly messages left by their neighbors and strangers and to leave messages of their own. In animals in which any face-to-face confrontation has the potential to escalate to deadly aggression, conducting their social life at a distance is the safest way to live.

Spraying and claw raking are the least endearing traits of domestic cats kept indoors, but this natural behavior is difficult to eliminate. One of the most common scent-marking behaviors of cats is spraying urine, which has been observed in all of the cat species that have been studied except for the puma. As cats travel, they stop often to spray, usually on vertical objects such as tree trunks or shrubs. The cat backs up to the object, raises its tail, and sprays urine backward. In most species, both males and females spray, but males tend to do so more often, and the cat penis is designed to let males direct urine at just the right height above ground: at nose level, so that the mark is in easy reach of its audience. Some cats have been observed to spray at very high rates. In a study of small wild cats in captivity, female Canada lynx, sand cats, Asian golden cats, and servals sprayed on average seven or eight times an hour. In the wild, male servals have been observed to spray about 40 times per kilometer traveled, or about 46 times an hour, and females slightly less often, 15 times per kilometer and about 20 times an hour.

There are situations in which cats refrain from advertising themselves through scent marks. In some species, such as leopards, transient individuals without territories do not mark, preferring to move about undetected. Also, females with young may stop marking and bury their feces when depositing them near the den. This behavior has been observed in bobcats and black-footed cats, perhaps to keep infanticidal males, as well as potential predators, from using odor clues to find the young. (Similarly, among pumas, only 2 scrapes of every 100 that John found were likely those of females, and these females were without kittens. Males were responsible for all of the other scrapes.) Female pumas with and without kittens cover their feces with piles of pine needles, as the kittens themselves do. But unlike domestic cats, wild cats do not always bury their feces and more often leave them conspicuously. Even the wildcats (Felis silvestris), from which the domestics arose, leave their feces in prominent locations where they will be found by others. Farm-living domestic cats bury their feces only on their home area and leave feces and urine on display elsewhere. It’s also been suggested that very small cat species are more likely to hide their feces to avoid being detected by predators. Pallas’ cats reportedly bury their feces, and it is possible that when Geoffroy’s cats deposit their feces high up in trees, they do so as a form of burial, in that the feces are hidden from nonclimbing predators.

Like all cats except pumas, cheetahs back up and spray urine on trees and other vertical objects. Performed by both sexes, but more frequently by males than females, urine spraying leaves scent messages that are very important in territorial defense.

In a friendly gesture, a female lion rubs her head on another’s. Such rubbing applies one cat’s scents to the other and is seen in all cats. Two cats smelling like each other may enhance their familiarity and reduce tension.

Cats rub their head and many different parts of their body against objects in the environment and against one another. They also rub their head, cheeks, chin, and neck against urine and other marks left by other cats and even roll their entire bodies on the ground or in urine, rotten meat, and other strong-smelling substances. Cheek rubbing between cats, most often in a breeding pair greeting each other after a separation, is a friendly gesture. In rubbing, cats both apply their scents and pick up other scents from their environment and from their social partners. When our pet domestic cats rub against us, they are doing the same thing. In making their odor more like that of their environment, and vice versa, cats may be camouflaging their own scent, which may make it more difficult for prey to smell their approach. Exchanging odors with social partners, either directly or indirectly by rubbing in their urine marks, may enhance their relationship: familiar, similar odors may reduce tension when they meet face to face.

Flehmen is a behavior mostly performed by males, but also sometimes by females. It occurs when males sniff a urine scent mark or the genital region of a female. It is also seen when a cat sniffs any novel odor. When flehming, a cat curls its upper lip and appears to be sneering or grimacing. At the same time, it stands very still and breathes slowly with a faraway look in its eyes, as if concentrating very hard. What it is doing, however, is exposing the two openings of the vomeronasal organ in the roof of the mouth, behind the front teeth, to better receive pheromones—the chemicals that send messages to the parts of the brain concerned with sexual behavior—and using its tongue to carry drops of whatever it is sniffing into contact with the vomeronasal organ. Pheromones are heavy molecules that cannot be picked up, or “smelled,” by the receptors that line the inside of the nostrils. Flehmen is probably universal in cats and is widespread among mammals. Most mammals—except marine mammals and, controversially, humans—possess vomeronasal organs that are important in detecting pheromones related to reproductive behavior.

This male lion is displaying a behavior called flehmen, which is a grimacing lip-curl that brings chemical signals called pheromones into contact with the vomeronasal organ in the roof of the mouth. This organ detects chemicals whose molecules are too large to be detected by the olfactory receptors inside nostrils. Pheromones convey information about a cat’s reproductive status.

German biologist Gustav Peters has devoted his life to studying the vocalizations of cats, and much of what follows is based on his work (Peters 1984, 2002; Peters and Hast 1994). All cats share a basic set of acoustic signals, with one or two vocalizations unique to one or more species. Except for purring and hissing, vocalizations are produced by oscillations of the vocal folds during exhalation; purring occurs during both exhalation and inhalation, and hissing may not involve the vocal tract at all. All cats spit, hiss, growl, and snarl during hostile interactions. The first three in the sequence indicate increasingly aggressive motivation, to the point where continued growling reveals a cat’s readiness to attack. The snarl, on the other hand, is a defensive sound; in some species, a submissive cat being attacked may shriek.

In friendly, close-contact interactions, cats produce noisy, low-intensity calls. In most species, this is emitted as a gurgle—pulsed sounds that, in some species, Peters compares to cooing in pigeons and, in others, to the sound of bubbling water. In lions and leopards, the equivalent call is a puff, which sounds like a series of stifled sneezes; in tigers, jaguars, snow leopards, and clouded leopards, it is a prusten, which is like the snorting of a horse.

All cats mew as well. A mew can range from a soft sound used by females in close contact with kittens all the way to a very loud roar used for long-distance signaling. In many species, the mew sounds similar to the familiar meow of domestic cats, but the comparable call in pumas sounds like a whistle, and in the big cats it includes grunts. Roaring is discussed in more detail below.

Other vocalizations have been heard in a few species. Pumas, and a handful of other cats, use a “wah-wah” call when two animals approach each other; Eurasian lynx and domestic cats chatter by clacking their jaws when prey is close but out of reach. Cheetahs chirp in several different situations (see Why Do Cats Roar, Chirp, or Meow?).

Until fairly recently, it was a common assumption that the cats could be divided into the big cats that roar but do not purr and the small cats that purr but cannot roar, a distinction believed to be rooted in differences between the hyoid structures in these groups. However, careful analysis by Peters and Hast (1994) has revealed that it isn’t necessarily so. In five species—lions, tigers, leopards, jaguars, and snow leopards—the hyoid contains a cartilaginous ligament; in the rest of the cat species the hyoid is all bone. Hence, many people believed that the cartilaginous ligament was necessary for roaring but prevented purring in the big cats, and vice versa in the small cats. This distinction also had taxonomic significance, because it was formerly used as one of the bases for dividing most of the felid family into two subfamilies: the Pantherinae and the Felinae (a third subfamily was composed only of the cheetah). However, modern analysis of both vocalizations and genetics refutes this. First, snow leopards do not roar, and, surprisingly, neither do tigers. In fact, what we generally call roaring in tigers is a sequence of calls whose acoustic properties are different from those involved in the roars of lions, leopards, and jaguars, which share a grunt call lacking in tigers’ “roars.” Neither do clouded leopards, now placed in the Panthera Lineage with the big cats, roar.

The anatomy of the vocal system of the roaring cats (including tigers) reveals how they make these very loud calls. According to M. H. Hast, “The entire vocal mechanism of the roaring Panthera … is analogous to the brass trumpet” (1989, 120). The vocal folds in the larynx are the mouthpiece, connected to the vocal tract—a straight tube that can be adjusted in length (formed of the supraglottal larynx and pharynx)—which at the other end is connected to the cat’s wide open mouth, analogous to the bell of the trumpet. Combining a high-energy sound generator (the vocal folds) with an efficient sound radiator (the vocal tract ending in the open mouth) enables a cat to “use its vocal instrument literally to blow its own horn with a ‘roar’ ” (p. 120).

Whether the big cats purr remains an open question, however. We know with certainty that 15 of the 40 cat species purr; there are no data on the presence or absence of purring in another 9 species. And about the remainder, including all of the Panthera Lineage species, scientists are unsure whether they purr or not, although Peters believes that all but the Panthera Lineage cats will be found to purr. As curator of mammals at the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park, John observed and listened to lions and tigers at very close range for many years; he never heard either species purr. So all we can say with confidence is that many small cats purr and none are known to roar, whereas big cats roar and may or may not also purr.

We’ve seen few things surprise visitors to the National Zoo as much as a chirping cheetah does. When first hearing this sound, they look for a noisy bird and are amazed when they realize that it’s actually a noisy cheetah. A cheetah’s chirp, a lion’s roar, and a domestic cat’s meow, despite the differences in how they sound to us, function as long-distance signals to other members of their species. All cat species have a vocalization for long-distance signaling. Although how various species use this signal is not well known, available evidence indicates that females use it to attract mates before and during their estrous periods and that both sexes may use it to maintain contact with desirable companions and to proclaim possession of an area so that conspecific competitors stay away.

Cheetahs chirp in three different natural situations. Estrous females chirp to attract males. Both sexes chirp when afraid or in distress. Males chirp when separated from members of their coalition and also chirp upon their reunion; females and young chirp when separated and reunited as well. In a study conducted at the National Zoo, we found that the chirps of different individuals were quite distinct, suggesting that cheetahs may be able to recognize one another by their chirps alone. What’s more, chirps have an acoustic structure with abrupt changes in frequency and amplitude, and they are emitted in a series. This is believed to facilitate locating the source of a call and may thus help separated individuals find one another.

Jon Grinnell and his colleagues have explored when and why lions roar in Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park (Grinnell 1997; Grinnell and McComb 2001). A roar actually consists of three different sounds. It begins with soft, low moans, progresses to loud, high-energy roar sounds, and concludes with a series of staccato grunts. Grinnell believes the grunts make the sound easy to locate (both males and females roar to maintain contact), and the roar sounds perhaps convey information about the individual’s sex, condition, status, and identity.

Male lions roar to proclaim their possession of a territory, but only while they are resident in a pride of females that they are prepared to defend from other males. Outside their territories, resident males are silent, as are nomadic males (those without territories). In situations in which males have nothing to defend, silence is golden. Roaring would only attract the attention of resident males, which would try to find and oust the intruders. The one exceptional situation, when a single nomadic male joins a single female in estrus, he roars to display his possession of the female.

Females also roar to advertise their ownership of a territory, even though there is some risk in this. Nonresident males are attracted to roaring females, but these are exactly the males that female lions want to avoid. Male lions that take over a pride of females immediately set about killing any cubs that can’t get away or their mothers can’t defend. The larger the number of females in a pride, the better able they are to defend their young from marauding male newcomers. Males looking for a pride seem to know this: they are much more likely to approach a single roaring female than a trio of roaring females.

On the other hand, Grinnell found that estrous females roar in order to attract males and also employ some trickery to incite competition between male coalitions. A larger coalition of males can usually best a smaller one, so it’s to a female’s advantage to be associated with a large coalition. A female sometimes tests the waters by sneaking off to mate with males in a nomadic coalition. Believing they are now territory owners by virtue of being in possession of a female, these males begin to roar, only to face the rage of the female’s resident males, which rush to defend their territory from the interlopers! If the new males are in a larger coalition, they may win the battle and oust the resident males; if not, the nomadic males are driven away. In either case, the female and her pride end up with the better male coalition. Females may have to employ such ruses, because male lions are loath to fight unless there’s a good chance of winning. One way to gauge their chances is simply by assessing the size of the potential opposition, and male lions make this assessment by listening to the other side’s roars.

The tiger’s long-distance call, although technically not a roar, is usually called a roar nonetheless (see Do Big Cats Roar and Small Cats Purr?). Their roaring is emitted in various situations, including by a female in estrus to attract a mate, by a male to announce his arrival, and by a female to call her young. Tigers may also roar after making a kill. It is very likely that roaring proclaims territorial possession, as it does in lions. If the acoustic qualities of an individual’s roar change with the animal’s size or health, another tiger may be able to tell if it’s worth the risk of fighting to take over a territory. But there’s more to a tiger’s roar than meets our ears. Scientists recently discovered that tigers are able to produce infrasonic sounds—very-low-frequency, deep sounds that humans cannot hear. The roar includes such sounds, which are notable for their ability to travel long distances even through dense vegetation, which tends to obscure higher-frequency sounds. This may help explain how tigers can stay in contact while occupying very large territories. Although we cannot hear these sounds, we may feel them, just as we can feel the pulsing bass of very loud rock music. Heard suddenly at close range, a tiger’s roar knocks you back like the blast of a speeding train.

Along with the cat’s meow, purring is the most familiar of felid vocalizations. People are so familiar with this sound that it is used in metaphors—the engine of a well-tuned car purrs, for instance. Purring conveys contentment; it says “all is well.” Purring is a close-range vocalization, heard most often between a mother and her young or in other close-contact friendly contexts, including between a person and his or her contented domestic cat. Purring is unusual in that it can go on for minutes—it is more like a song than a shout—and continues while the cat both inhales and exhales. Very young kittens purr, even without interrupting nursing. Purring is generally a low-intensity soft sound, which may keep predators from detecting and following the sound to the den. People can hear domestic cats purring from at most 3 meters away, but the purring of larger cats generally carries farther than that of smaller cats. Because cats usually purr when they are in body contact, Gustav Peters believes that “the body surface vibration during purring may serve as a tactile signal in addition to the auditory one and may even be at least as significant in conveying the senders’ message” (2002, 264).

Among the cats known to purr are the cheetah, puma, and jaguarundi in the Puma Lineage; the serval; the ocelot, margay, and oncilla in the Leopardus Lineage; the bobcat, Eurasian lynx, and probably Canada and Iberian lynxes in the Lynx Lineage; the caracal in the Caracal Lineage; the wildcat and black-footed cat in the Felis Lineage; the Asian golden cat in the Bay Cat Lineage; the marbled cat; and the leopard cat in the Leopard Cat Lineage.

Approached from the point of view of adult females, cat reproduction is easily summarized. Adult females of the larger cat species—lions, tigers, jaguars, leopards, snow leopards, pumas, and cheetahs—produce litters every other year; smaller cats do so about annually or, rarely, twice a year. The exceptions are some of the small South American cats—ocelots, margays, and oncillas—which sometimes skip a year, and domestic cats, which can produce as many as three litters in a year. Thus, in an idealized scenario, a female lion or tiger, for example, mates with a male, produces a litter of young 100 or so days later, and resumes sexual activity nearly 2 years after that, when her young become independent and she is able to care for new ones. This summary, however, hides a great deal of variation, and females rarely reproduce like clockwork.

Whether the young of any particular litter survive to independence influences the following birth interval, and, as we describe below (in How Long Do Cats Live?), infant mortality can be quite high. In cats that are not strictly seasonal breeders (and many species are not) females will mate soon after losing a litter. Male lions take advantage of this by killing the young in a pride they’ve newly taken over, so that the mothers will breed with the newcomers more quickly, within a few days or weeks. This increases the chances that the new males’ offspring will be born and mature before they are ousted by another male group. In these cases, the birth interval will be less than the average 2 years.

Other factors act to lengthen the birth interval. Females do not conceive in every period of estrus. In one well-studied population of pumas, fewer than one-quarter of breeding associations between a female and a male or males resulted in kittens being born 92 or 93 days later. Studies of tigers and lions suggest that the chances of conception in any one estrus in these species are only 20 to 40 percent, and only 2 of 13 courtship associations (15 percent) observed in leopards in South Africa resulted in births. Female lions mating with the same males that fathered their previous litters take fewer estrous periods to conceive than females mating with new males.

Many female cats will continue to come into estrus until they conceive. Estrous cycle length varies considerably, even among some closely related species. The lion estrous cycle averages 16 days, while that of leopards is 46 days, and jaguars 37. There is also considerable individual variation within some species. The estrous cycle of tigers has been reported as both 15 to 20 days and 40 to 50 days, for instance.

Canada lynx are seasonal breeders, with mating occurring during about a month in the spring, so that babies are born in the warm months of May and June and have time to grow fairly large before the weather turns harsh. Females exhibit only one estrous cycle per year, and those that fail to conceive or lose their litters will not mate again until the next year. Moreover, the reproductive success of Canada lynx corresponds with changes in the abundance of hares, which form the mainstay of their diet. When hare numbers crash, few or no females produce live young in the first year of the low numbers, and few young are born—and few of these survive—in the second year. During hare abundance, however, pregnancy and birth rates range from 73 to 100 percent for adults females, with 50 to 83 percent of young surviving.

Snow leopards live in habitats with harsh winters as well, and nearly all births occur in the late spring, with more than half in May alone. Estrus appears to be very brief, and a female has at most only one estrous cycle each year. Females that lose litters seldom mate again until the following winter, while females raising young will not become receptive to mating until the second winter. Similarly, Amur tigers, which inhabit the northern temperate forests of the Russian Far East and northeast China, tend to give birth in the spring.

Tropical cats are generally less seasonal in their breeding, and, in many species, females can become pregnant in any month of the year. However, births may cluster before peaks in the availability of prey to help ensure that mothers have plenty to eat to support the high-energy demands of lactation. Servals, for instance, are born about a month before the peak breeding season of their rodent prey. South African leopard births peak during the birth peak of impala, in the early part of the wet season. Not only are prey more available then; they are also more easily caught when wet-season vegetation gives the cats better stalking cover. Young leopards, too, are better concealed from predators when they are hidden among the vegetation.

How many times a female cat reproduces in her lifetime is not known with certainty for any species. One exceptional female tiger in Nepal’s Royal Chitwan National Park lived for 15 years, 10 of them in the same territory. She produced five known litters of cubs; her first was born in 1975, her last in 1985, so she actually did reproduce, on average, about every 2 years for 10 years. Eleven of her 16 total young survived to independence. Female lions produce their first litters at 3 years of age, give birth on average every 2 years, and for most of their life, litter size is constant, averaging 2.5. At 14 years, however, average litter size drops to 1, and by 17, if they survive so long, they no longer reproduce. According to lion biologist Craig Packer, “Maternal survival is only important during the first year of a cub’s life, so when a lioness reaches the age of fourteen … she can expect to live another 1.8 years—long enough to raise the last cub born” (1998, 26). Thus, although a female lion could potentially raise 15 or 16 young in her lifetime, she rarely would. Sunquist and Sunquist (2002) report that one Serengeti lion had seven litters in 12 years but raised only two of those litters, for a total of six cubs.

Female cheetahs live particularly short lives in the Serengeti. A 25-year-long study revealed that the females that survived to independence lived on average just over 6 years (at a maximum of 13 years) and produced fewer than two cubs that survived to independence. Among the 108 females in the study group, 8 females raised between 7 and 10 cubs to independence, and 55 raised none. Females gave birth for the first time at about 2.4 years of age and experienced average birth intervals of 20 months when they raised cubs to independence. Females that lost cubs swiftly mated again, sometimes as early as 2 to 5 days after the loss.

Except for lions, in which males and females share a territory and interactions are frequent, male and female cats seldom meet face to face, although individuals living in the same neighborhood know one another. Male territories generally overlap those of more than one female, but they avoid using the same areas at the same time. Their mutual avoidance is believed to be mediated by scent marks (see How Do Solitary Cats Communicate? and What Is Scent Marking?). Both males and females deposit scent marks. They do this primarily by regularly spraying urine on trees and bushes, making scrapes of bare soil on which they may also urinate or defecate, and depositing feces in prominent locations as they travel through their territories and patrol their territorial boundaries.

These scent marks are like signs: a fresh marks says, “I’m working here now; you find somewhere else.” A stale sign says, “I’ve moved along; it’s safe for you to come in.” As a female approaches estrus, however, the message changes. Changes in the chemical composition of the urine correlated with the rise in estrogens that precedes full estrus and ovulation are read by males as “Come find me; I’m ready to mate.” To ensure that the local male gets the message, a female increases the rate at which she scent-marks. The male, in turn, routinely patrols all areas of his territory to check on the status of the females living there.

Other behaviors performed more frequently by female cats in estrus include restlessness, rolling, cheek rubbing, body rubbing, and vocalizing. These behaviors among female domestic cats in estrus are familiar to many people and may even be directed at their human caretakers. Wild cats observed in estrus appear to behave similarly, although most of their behavior has been observed in captivity.

Females approaching estrus and in it may also use their species-specific, long-range vocalization to call in males. Female tigers, for instance, sometimes roar but not always. Sunquist and Sunquist (2002) describe a female tiger that roared during five consecutive estrous periods, some days roaring day and night, as many as 69 times in 15 minutes, and then roared not at all during the next estrous periods they observed.

Jon Grinnell recounted an episode he observed while studying lions in the Serengeti:

As part of my research I tranquilized a number of male lions to take blood samples and to attach radio collars to aid in relocating them. Once, I immobilized a male in consort with an estrous female. I hadn’t seen the two mating before this, but after the male was fast asleep the female decided it was time, and walked sinuously by his sleeping form, back and forth, her tail lashing her receptive scent under his nose. When after a few minutes of this he still hadn’t responded, she walked off—one can only guess at her thoughts—and started roaring, even though it was midday and a highly unusual time for a lion to roar. She continued roaring until the male awoke from his drugged sleep and rejoined her. Why did she roar? Probably the simplest explanation is that since she was in estrus and her first male had lost all interest in her, she meant to attract a new one. (Grinnell 1997, 12)

Roaring and other long-distance vocalizations may attract not only the resident male but also other males looking for a chance to mate. Transient males moving through the area but avoiding another male’s territory may miss a female’s scent-mark advertisement but still hear her call. Possibly females vocalize in order to attract other males to the scene, to create a “may the best man win” competition among them (see Why Do Cats Roar, Chirp, or Meow?). Females in many mammal species, including elephant seals, right whales, and bison, appear to incite competition to ensure that the highest-quality male available fathers her young. Breeding encounters have been observed in the wild in only a few species, but in tigers, jaguars, pumas, cheetahs, wildcats, caracals, and others, estrous females are often attended by more than one male.

A female domestic cat may mate with multiple males that attend her without much fighting among themselves. As in lions, these males are usually relatives, which may reduce the competitive urge. But dominant males likely achieve most of the matings. Male lions in a coalition do not have equal access to a female in estrus; one male often monopolizes the female for much of her estrous period, which lasts 4 days or so. Only when his interest wanes will other males get a chance to copulate.

Once a male and a female cat have found one another, a period of careful, high-tension courtship follows. When two such predators get together, there is always the chance that a false move on either’s part will escalate into lethal combat rather than copulations. The female is initially coy, aggressively rebuffing the male’s attempts to get close and mount her, even though she may have solicited his advances by walking sinuously by him, rolling in front of him, and touching him. The male meekly gives way, only to try again and again until gradually the female becomes fully receptive and accepts his advances. When the female permits, the pair may lick and rub each other. Finally, the female adopts a crouching posture, called lordosis, which makes her accessible to the male. He then mounts and they copulate. The male may or may not hold the female’s neck between his teeth during mounting and copulation, but immediately after ejaculation, the female twists her body to dislodge him, often swatting at him with her paw. Intromission or ejaculation may stimulate a copulatory vocalization by male or female or both. Female tigers, for instance, yowl after ejaculation, as male snow leopards and both male and female pumas do.

Once the male and female begin copulating, they do so with reckless abandon in many species. Individual copulations are generally brief, lasting from a few seconds to less than a minute, although caracals are reported to engage in long copulations ranging from 90 seconds to 8 or 10 minutes. Copulations are usually numerous, however. Tigers may copulate tens or hundreds of times during an average 7-day estrous period. In one study, puma pairs were observed to copulate 2 to 20 times per day over 6 to 11 days, and in another study, a pair copulated 23 times in 10 hours. Captive jaguar pairs have been observed to mate 100 times a day over 7 days. A captive lion pair copulated 360 times in 8 days, and lions in the wild have been observed to copulate every 20 minutes or so over several days, during which time males don’t even bother to eat. In captive snow leopards, copulations lasted from 15 to 45 seconds and were repeated 12 to 36 times a day for 3 to 6 days. Captive female black-footed cats exhibited very short periods of receptivity—just 5 to 10 hours—but pairs still copulated as many as a dozen times during that time. Ocelots copulate just 5 to 10 times a day for about 5 days. Cheetahs are highly secretive breeders, and mating is rarely seen in the wild. The estrous period is short, just 2 or 3 days, and brief copulations usually occur at long intervals and at night. Big cats have the luxury of enjoying lives free from the threat of predators. This may account for their flamboyant matings over many days compared with the more discreet pairings of cheetahs and the small cats for which there are data.

A male and female lion mate repeatedly, as often as every 20 minutes for the several days of the female’s estrus. Other big cats copulate at similarly high rates, whereas small cats tend to be more restrained, perhaps because of their greater risk of a predator taking advantage of their distraction. Cheetahs, which are heavily preyed on by lions, are almost never seen mating.

Cats are believed to be induced ovulators, but this has not been demonstrated for most species. Induced ovulation means that the stimulation of copulation is required for a female to ovulate, unlike, for example, human females, who spontaneously ovulate about every 28 days even if no male is present. Induced ovulation may be an advantage in species in which males and females live widely separated from one another. Waiting to ovulate until copulation actually occurs ensures that opportunities for successful matings are not missed. This idea is supported both by the frequency of mating among female cats and by the special attribute of the penis of males, which is covered with small, stimulating spines. However, it appears that induced ovulation is not a hard-and-fast rule in cats. Lions, tigers, and leopards may be spontaneous ovulators, at least under some captive conditions, and spontaneous ovulation is the norm in bobcats, Canada lynx, and some fishing cats. On the other hand, multiple copulations may increase the probability of conception: a captive female tiger that copulated 100 times during one estrus conceived but did not do so during an estrus in which she copulated only 30 times.