Pulitzer Prize–winning biologist Jared Diamond refers to the mechanisms of recent species extinctions as the “arsenal of species extermination,” or the “Evil Quartet”: habitat fragmentation and destruction, overkill, effects of introduced species, and secondary extinctions (the last of which occur as a result of the extinction of another species or disruption of ecological processes). Another Pulitzer Prize–winning biologist, E. O. Wilson, refers to these as “the mindless horsemen of the evolutionary apocalypse.” Extinction and human presence go hand in hand. Wild cats are in decline because they are being killed accidentally, such as by vehicles, or deliberately, for revenge or to supply illegal markets. The habitat they require is disappearing. The prey they need to survive are overexploited by people or are dying from introduced diseases. Most people aren’t aware of or do not appreciate what wild cats need to survive. In many parts of the world, there are no effective programs for the protection of wildlife and their habitats in general or for cats specifically. Cats threaten people and their livestock, and the results are continuing confrontations and dead cats. We know that most, if not all, recent extinctions of animal species can be related directly or indirectly to human activity. If wild cats are to remain a vital part of our legacy, we must act to make it so.

It has only been since the 1970s, with the passage and implementation of the US Endangered Species Act, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES), and the identification of the threats to many cat species with the publication of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) (now the World Conservation Union) red data books, that the challenges presented by the loss of species have become more widely understood by the general public. Because conservation biologists are paying close attention, we know that one or more populations of every wild cat species are threatened or endangered.

Almost inevitably, conservationists posit that the continued rapid growth of human populations, combined with an increase in per capita consumption of resources, is placing unprecedented demand on the Earth’s renewable and nonrenewable resources, from trees and soil to oil and diamonds, leading to increased threats to all endangered species, including wild cats. We are in an environmental crisis of our own making, and we are losing our biodiversity. The threat to the continued existence of wild cats is but one loud roaring reminder of our critical conservation issues.

Recently, biologists have been fine-tuning our understanding of the role of human population size and its relationship to the rising threat to birds and mammals. They have advanced our awareness by comparing the human population density of most of the world’s countries with the proportion of species threatened there. A surprising finding is that only about one-third of the variation among the threat levels is directly attributable to the density of humans. That leaves about two-thirds of the variation in extinction threat to be explained by other factors. As Michael McKinney (2001), the author of this insightful and comprehensive report, has explained, other factors, such as the standard of living and government policies, can influence extinction threats in a nation, independent of its human population size. Traits of endangered birds and mammals themselves also make them prone to extinction.

Across the world, the human population is increasing faster than the proportion of species threatened. In other words, few people may do far greater damage in pristine systems through hunting and land clearing than many people do by living at high densities in urban environments. Even in large areas, a few people can do immense damage. Nowhere is this clearer than on islands, where people have catastrophic impacts, such as by releasing domestic cats, which feed on native species with devastating effect.

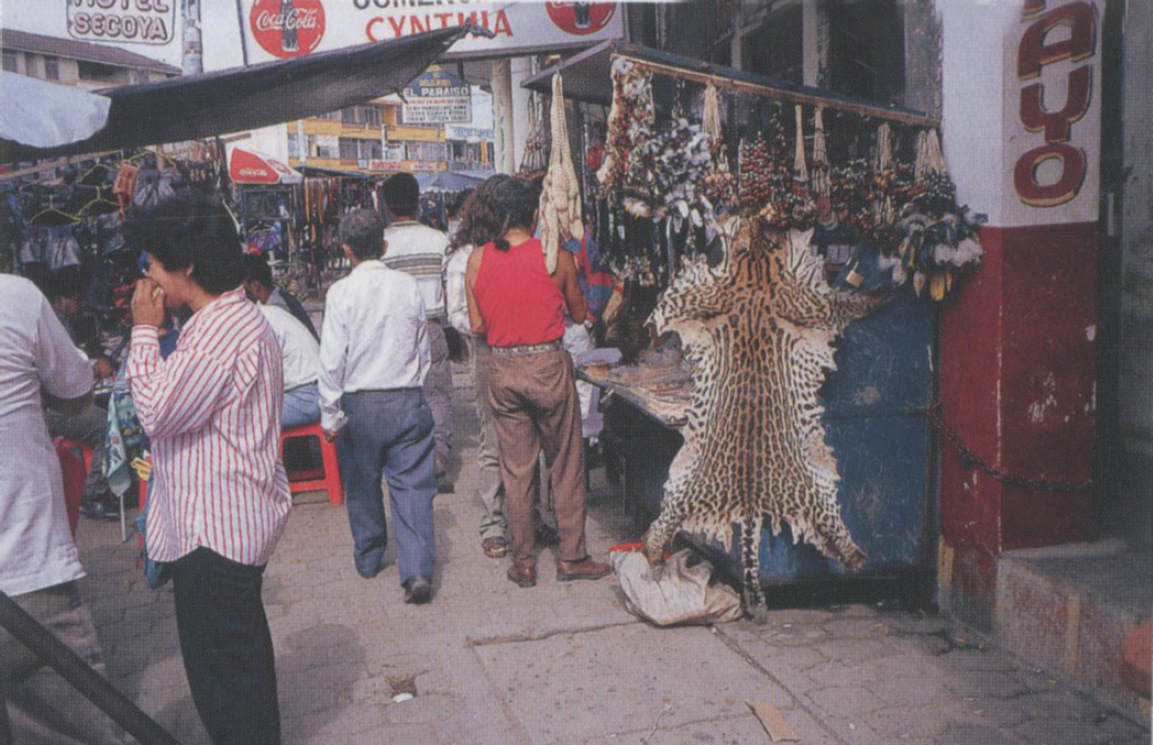

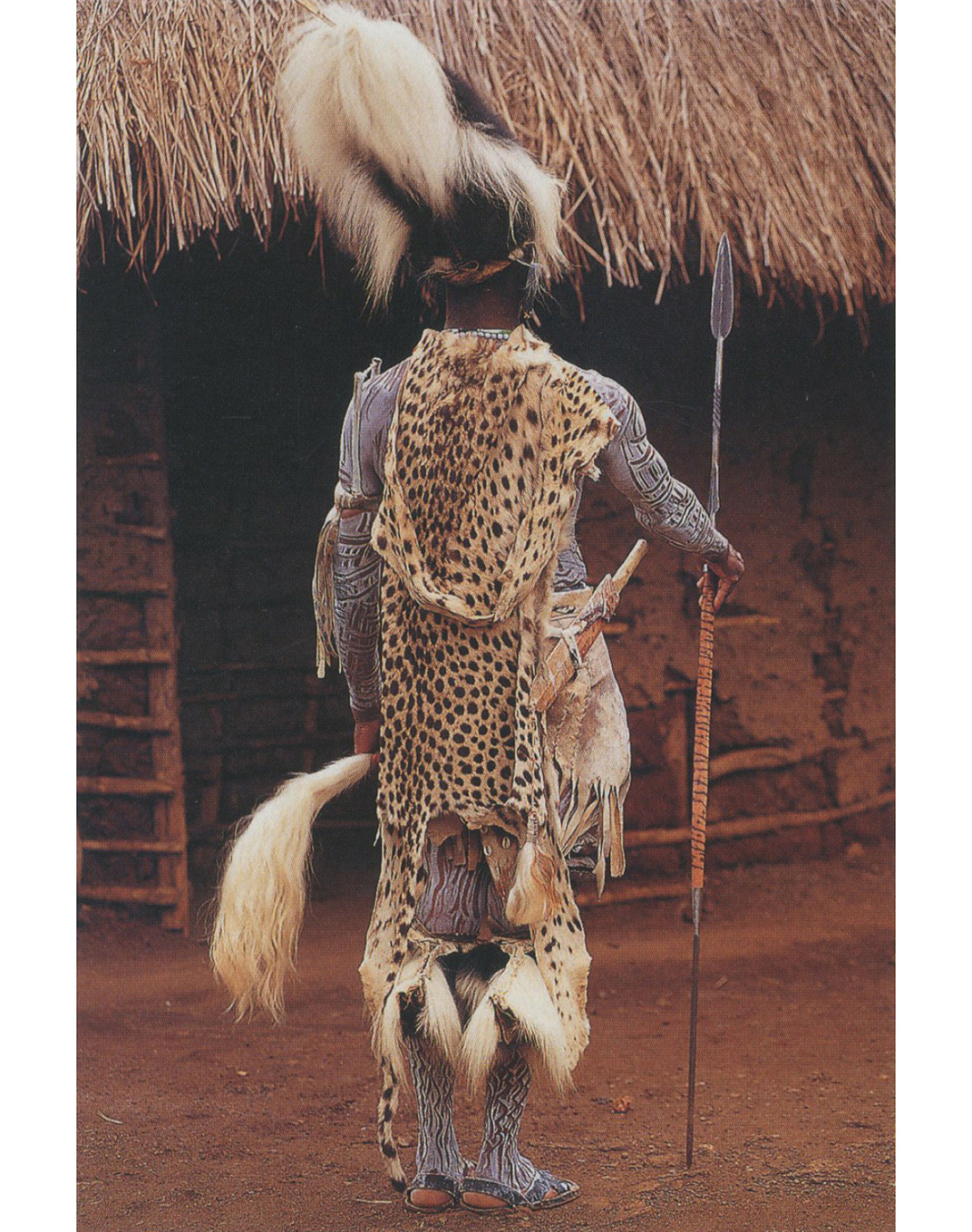

Many people blame human population growth for the decline of cats and other wildlife, but human choices will determine the ultimate fate of wild animals. As long as people choose to purchase spotted-cat furs, for instance, they will appear in markets until the last spotted cat is gone.

Without question, though, human population density is part of the problem. McKinney found that Asia contains the nations with the highest proportions of threatened species and the highest number of people. Africa and Latin America contain many nations with small human populations and a relatively low proportion of threat to their mammal and bird species. However, John has worked on cat conservation issues in many Asian countries and cannot imagine telling a local official, “The problem here is that you have too many people.” The critical issue is what people do, not simply that they exist. And what people do is strongly influenced by their standard of living, government policies, long-held cultural traditions, and what they value in general. For example, deforestation and other kinds of habitat loss, a major cause of extinctions, are directly correlated to human population density, but effective government policy can stabilize the amount of forest cover retained and even restore what has been lost.

In a crowded world, large carnivores are the most challenging faunal group to conserve. Conservation biologists call this the large carnivore problem. However, enlightened government and management policies can offset the impact of high human densities. Large carnivore populations can increase after favorable legislation is implemented, despite further increases in human population density. The puma in North America and the Eurasian lynx are examples of species that have benefited from strong positive policy initiatives. This finding is encouraging for conservation biologists as they devise strategies to protect and restore cat populations in other areas of the world, where, historically, policies have not been large-carnivore friendly.

Leopards, like all large carnivores, are among the most difficult animals to conserve in our crowded world. They require large areas with plenty of prey (prey that people also find good to eat) as well as a certain amount of solitude for females to raise young, and they inspire equal amounts of fear and admiration among the people who share their habitats. However, strong conservation policies and programs, such as those in North America and Europe that have enabled the recovery of pumas and Eurasian lynx from the brink of extinction, have shown us that a future for large carnivores is possible.

Habitat destruction, including its degradation and fragmentation, is the most pervasive threat to endangered species. This destruction results from several different activities: the conversion of land to agriculture or the adoption of certain agricultural practices, including livestock grazing; mining and oil and gas exploration and development; logging; infrastructure development, including road construction to support logging and mining activities; military activity; outdoor recreation, including off-road vehicle use; water developments; pollutants; land conversion for urban and commercial development; and the disruption of fire ecology including fire suppression. The human footprint is huge, and it covers the globe.

Conservation organizations, including the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park, the Wildlife Conservation Society, Conservation International, and the World Wildlife Fund, have been mapping the human footprint and searching for “the last of the wild,” that is, areas little affected by human activities where we might save wildlife. As you might expect, some biomes have more and larger wild areas than others. More than 67 percent of the area of North American tundra is wild, but no wild cats live there. The wildest areas of Old World tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forest are all in China, where as many as 10 different wild cat species live. But wild areas encompass less that 0.03 percent of that biome. Large areas of Alaska and northern Canada and Russia are still wild, and these are home to Canada and Eurasian lynxes and the puma in western North America. Vast stretches of the African Sahara and the Arabian Peninsula are wild; this is sand cat country and, once and potentially again, cheetah country. The once vast and foreboding rain forests of central Africa have been carved up, but some large wild tracts remain, home to the African golden cat and the leopard. Large areas of the Tibetan plateau and its mountain ranges, home of the snow leopard, are wild, as are the deserts of central Asia, where the Pallas’ cat lives at the edge. Some wild rain forest remains on Borneo, which might protect the bay cat and leopard cat. The Amazon Basin still has considerable wild lands where the jaguar, puma, jaguarundi, ocelot, margay, and oncilla live. But we cannot rely on the “last of the wild” to save wild cats. Rather, we have to figure out how to create conditions and processes that let wild cats live in human-dominated landscapes.

Because wild cats are at the top of the energy pyramid, human alteration of food webs is a primary, but little appreciated, threat to cats. People appropriate more than 40 percent of the net primary productivity—the green material—produced on Earth each year, with a profound effect on most natural food webs. People appropriate resources when their livestock graze on plants that wild ungulates need to survive. People also kill the large cats’ primary food, large ungulates, to feed themselves and to keep those ungulates from eating their crops. Vast areas that are potential habitat for tigers, for example, are devoid of prey through much of the tiger’s range, from the Russian Far East through much of south and Southeast Asia, where less than 20 percent of the potential habitat is protected in reserves. Hunters kill European rabbits, reducing the primary prey of the critically endangered Iberian lynx. Inevitably, hunters complain that carnivores take what they consider to be their “game.” In the past, governments put bounties on the heads of carnivores, and poisoning, trapping, other means of killing them have been devastatingly effective. Today, conservation biologists try to work with hunters and devise coexistence recipes based on understanding and tolerance.

Various populations within wild cat species were once broadly linked by favorable habitat so that cats could move among them. Habitat fragmentation, in which human activities cut the linkages, divides wild cat populations into smaller and more isolated units; cats live on habitat islands in a sea of humanity. In a metapopulation, which is a set of local populations connected by dispersing individuals, the movement of those individuals is highly restricted because of the hostile conditions between habitat patches. Wild cats living in small habitat islands cannot move through the hostile human landscape to reach other areas, where other individuals of the same species may live. Neither can they move to colonize another area of habitat. Wild cats tend to become extinct in these small patches. A disease epidemic, a rash of poachers, an upsurge in predators, or a catastrophe such as a flood or fire may wipe out all of the cats in the patch. Or, simply by chance, all the young produced in a very small population are either males or females, or no young are produced at all. Genetic deterioration due to inbreeding is a further threat. Moreover, once the cats go extinct in a patch, it cannot be recolonized because of the loss of all the corridors and links to where other wild cats of the same species remain. Conservation biologists call this the extinction vortex.

Species with large body size, low abundance, low reproduction rates, specialized habitat requirements, and isolated populations are thought to be most vulnerable to extinction. Large carnivores with large home ranges, such as tigers and lions, are prone to local extinction because their ranges make them liable to move outside their protected areas and come into conflict with humans. To protect these species, land-use policies must include not just reserves but also large buffer zones around reserves, where these animals are tolerated by people and also receive good protection. The persistence of carnivore populations depends on their individuals’ abilities to disperse through various habitats that offer less than ideal conditions. Tigers, which evolved in forested landscapes, are poor dispersers in the landscape mosaics they live in today, because they do not like to cross open areas created by agricultural activities. Leopards, on the other hand, are masters at dispersing across the most desolate habitats, making them less vulnerable to human activities. Large-bodied carnivores such lions and tigers are more prone to local extinctions, whereas smaller cats such as leopards and servals are more likely to persist because of their dispersal abilities. Many smaller cat species also seem to tolerate living among people. Fishing cats live next to the airport in Colombo, the capital of Sri Lanka, and jungle cats and leopard cats commonly live near Asian villages.

Wild places are disappearing, so ways must be found to enable cats to survive in human-dominated landscapes. Setting aside large protected areas, bans and limits on hunting of both predator and prey, growing appreciation of the needs and values of wildlife, and the increasing movement of people from rural to urban environments have contributed to the recovery of pumas in the western United States.

Living in very large remote areas isolated from human disturbance helps cat populations to survive, but there are few such areas. To compensate for the inadequate size, isolation, and remoteness of reserves, conservation biologists are trying to maintain or restore habitat connections between them, so that cats can move from one to another. Otherwise, cats attempting to disperse from the reserves are simply lost between them in the “sinks” created by human conditions.

Wild cats’ ecological adaptability, dispersal efficiency, and tolerance of human activity are the traits that determine how they will respond to the human-dominated environments that are the norm today. Biologists simply do not know or have not been able to define the tolerance of most wild cat species, and this information is essential to designing management plans that can lead to recovery of their populations.

Changing economic and political conditions affect wild cats in different ways. When economic conditions worsened after the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, the population of Amur tigers that had been slowly recovering took a nose dive because of intense poaching. The change in the political system relaxed protection and, at the same time, created access to other markets, especially along the newly opened border with China. Poachers took advantage of this, just as they continue to take advantage of social and economic turmoil in many other countries.

In a more positive example, western North America has changed from an economic base of predominately rural farming, ranching, logging, and mining to one more dependent on industries such as financial services and computer and information technology. More people live in towns, and they tend to use wild lands for recreation rather than resource extraction. These “new westerners” view wildlife, especially the large carnivores, in a positive light, as something that adds value to their life. Here people are encountering pumas directly and are learning to live with them. The remaining ranchers, on the other hand, view these same animals in a negative light because they threaten the ranchers’ livestock and their already impaired livelihoods. These tensions have to be carefully negotiated in the political process. So far, the balance is in favor of the puma and the wolf, whose populations are now much larger than they were a century ago. A negative effect of this economic shift, however, is that large landholdings are being divided into small “ranchettes,” which fragment habitats, or developed as subdivisions, which intrude into the winter range of deer and elk.

In south Asia, many protected wildlife areas, including tiger reserves, have substantial populations of people living in them. But people are increasingly willing to move out of reserves to places where they have access to life-changing benefits such as schools, better health care, and jobs, and this benefits the wild cats in these areas. Conservation biologists are learning that protecting wildlife can often best be achieved by providing rural people with new job skills, including those that allow them to join the computer age.

People also kill cats and other wildlife to sell their parts and products as food and medicine. Most of this trade is illegal across international boundaries, but the laws haven’t stopped it. Furthermore, all the countries involved in it, whether they are where the wildlife live and are hunted or they are distant countries where the trade takes place, are having an increasing impact on the wildlife. For example, until recently, the largest and fastest growing markets for medicinal products reputed to contain tiger bone were the United States, Canada, and western Europe. Relatedly, a number of “tiger farmers” in the United States have been recently convicted for raising tigers for their hides and to sell the meat to specialty shops.

Increasing affluence in Asia, as well as large, relatively wealthy Asian communities in North America and Europe, have fueled an increase in the demand for traditional medicines that incorporate tiger bone and other wildlife parts and products. Curtailing the illegal wildlife trade through education and law enforcement is essential. (Photograph by Judy Mills)

Wild cat parts and products are used both as part of traditional medicine systems and as food. In the past, the cost of products purported to contain wild cat parts generally placed them beyond the reach of the average person. As Asian economies grow, however, and individuals accumulate more wealth, their buying power increases. With an increase in disposable income, these products become affordable, thus increasing the market demand and resulting in more commercial killing to supply that demand. Moreover, in the consumption of these products, the distinction between food and medicine becomes blurred; many think whatever is good for you in small amounts is better for you in large amounts. So rather than a taking a pinch of tiger bone to treat an ailment, the newly rich indulge in a dinner of tiger penis soup, which is also a status symbol. This behavior is leading to the wholesale destruction of all wildlife in the tropical forests throughout Southeast Asia. As the actor Jackie Chan and other celebrities point out in the public service announcements broadcast on television in many Southeast Asian countries and in China: “When the buying stops, the killing will too.” And that is conservation’s premiere challenge: Stop the buying. Get rid of the demand, and the rest can follow.

The most endangered cat, not to be confused with rare, is the Iberian lynx. A rare animal is not necessarily an endangered one; an animal that is currently endangered may once have been quite widespread and common. The Iberian lynx is such an animal, once widespread in Spain and Portugal. It was regularly hunted and considered by some to be vermin. Formerly thought to be a subspecies of the Eurasian lynx, the Iberian lynx has now been shown to be a separate species. But even though it is arguably the best-studied small cat in the world, it is a species we may see go extinct in our lifetime.

The first blow to this species came when the poxvirus myxomatosis was introduced from South America in the 1950s, and European rabbits, which had no natural immunity, were decimated. Rabbits form most of the Iberian lynx’s diet, so their decline hit these cats hard. Just as the rabbits were developing some immunity and beginning to recover, a new virus, hemorrhagic pneumonia, hit in the late 1980s, again causing a high mortality in adult rabbits. These diseases that killed the Iberian lynx’s prey, along with continued poaching, being killed by cars as these cats try to cross highways, and land-use changes that do not favor the lynx or its prey, are reasons this species may not survive. If that is not enough, a case of bovine tuberculosis was recently found in a dying lynx, the first ever such case in a wild cat. Populations of red deer, fallow deer, wild swine, and feral cattle live within the habitat of the lynx in Spain’s Doñana National Park, and these species could be reservoirs for the disease.

Only two populations of this lynx remain in Spain, one in Doñana National Park and the other in the Sierra Morena. Another population may remain in Portugal. Each population consists of only a few tens of individuals.

No cat species that we know of has gone extinct within historical time, but many populations or subspecies have been extirpated. The tiger subspecies that lived on the Indonesian islands of Bali and Java, those that lived around the Caspian Sea, and the wild tiger of central China are gone. The eastern puma is gone except for a remnant population in Florida, called the Florida panther. The fishing cats that lived on the delta of the Indus River are gone. The South African Cape lion is gone, and so are the lions, leopards, cheetahs, and servals that lived north of the Sahara. The list goes on. Basically, only domestic cats, both feral and pets, are secure.

Who decides if a wild cat species is endangered or threatened with extinction? Most countries have their own endangered species laws today, each country with its own definition. Internationally, we rely on the World Conservation Union’s 2003 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Unlike the US Endangered Species List, the Red List does not have the force of law, but its categorization of species, from extinct to critically endangered to being of least concern, is considered scientifically authoritative.

CITES, or the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna, was established in 1975 to ensure that trade in wildlife species is managed for their sustainability. As participants in this treaty, individual countries sign on as parties to the convention and agree to abide by its rules. Species are listed in CITES appendix I, II, or III: appendix I is the highest category of threat, and trade in these species, which threatens them with extinction, is severely restricted; trade in species listed in appendix II must be based on sustainable harvests. In appendix III, countries can list the protected native species that live within their borders, in order to prevent or at least restrict their exploitation.

The Red List includes one critically endangered species of wild cats, which means it has a high probability of extinction within five years or two generations, whichever is longer. Five more are listed as endangered, 13 as vulnerable, 7 as near-threatened, and 13 as those of least concern. There are 21 wild cat taxa in CITES appendix I and 20 in appendix II. Some species listed on the IUCN Red List are listed only in appendix II of CITES (the bay cat is an example), whereas other species (such as the caracal) are listed as species of least concern yet appear in CITES appendix I. The reason for this disparity is the narrow scope of CITES’s focus on trade. Although the bay bat is considered endangered, it is not clear that this species is affected by the wildlife trade, but the caracal is or may be affected by it. These species are shifted from one category to another all the time, with the greatest number of shifts from appendix II to appendix I.

Conservationists fear that the Iberian lynx may be first cat to go extinct since the saber-toothed Smilodon did about 10,000 years ago. This cat is beset by nearly everything that can threaten a species: small distribution in Spain and Portugal, continuing loss and fragmentation of habitat, hunting pressure, the decimation of its specialized diet of rabbits by introduced diseases, introduced disease killing the lynx themselves, and high mortality as roadkills. (Photograph by John Seidensticker)

Appendix 2 in this book lists the status of each wild cat species on the 2003 IUCN Red List, the US Endangered Species List, and CITES. The threat categories of wild cats in the Red List and the US Endangered Species List contain some differences. The US list generally puts species in a higher threat category than the Red List. Some of this disparity is the result of insufficient information; some, the result of the lengthy review process necessary to change species from one category to another; and some, the result of genuine disagreement among biologists or governments. All would agree, however, that any wild cat species at any risk of extinction is one too many.

In regard to animal species, the words umbrella, flagship, landscape, keystone, and indicator have distinct but overlapping meanings. Conservationists use various wild cat species as flagship, umbrella, and landscape species, and when they influence ecosystem processes, biologists call them keystone species or indicator species.

Flagship species are popular, charismatic species that serve as symbols and rallying points to stimulate conservation awareness and action. Flagship species are about marketing; for instance, tigers make a good flagship species because people value them so highly—more than, say, skunks. People have inherently strong feeling about cats, which makes them useful as flagship species for conservation biologists trying to increase awareness about threats to cats and life’s diversity in general. Cats are charismatic; many people relate to them in positive ways, so some species have become symbols and leading elements of entire conservation campaigns. Appeals on behalf of charismatic species usually raise more money than those on behalf of less charismatic species. Tigers probably rival giant pandas as the top poster children for immense international and regional conservation activities. Organizations dedicated to securing a future for tigers include tiger in their name. Save The Tiger Fund, the Tigris Foundation, and the Tiger Foundation are examples. Other cats that have emerged as flagship species include the Florida panther, cheetah, lion, Iberian lynx, snow leopard, and jaguar.

The tiger, like all cats, is also an umbrella species. This means that its areas of occupancy and home ranges are large enough and its habitat requirements are broad enough, or exacting enough, that setting aside a sufficiently large area for its protection will automatically protect many other species that may also need large blocks of relatively natural or unaltered habitat to maintain viable populations. Protecting umbrella species may preserve genetic and ecological processes that maintain diversity. So the concept of umbrella species is a big one.

Tigers and other large cats are also landscape species, in that it takes the conservation of entire large regional landscapes to meet their ecological needs. The term landscape species combines the concept of flagship species, with all its charismatic content, and the concept of umbrella species, with its content of ecological processes, both broadly spatial and species inclusive. The Terai Arc, which extends 1,000 kilometers across northern India and Nepal, is one such tiger landscape that conservationists are trying to create through a combination of protection and restoration.

The beauty and charisma of tigers have make them symbols of the conservation movement, helping to create support for efforts to secure a future in the wild for them and all other threatened but less appealing creatures. In addition to this role as a “flagship species,” the tiger serves as an “umbrella species.” Successful efforts to save tigers, with their need for huge, relatively undisturbed habitats, will protect other wildlife in those habitats from the threatening rain of adverse human activities.

Biologists studying intertidal invertebrate communities coined the keystone species concept. A keystone species is any that plays a vital role in a biological community. It is a species that through its size, or activity, or productivity has a greater impact on its community or ecosystem than is expected on the basis of its relative abundance. The real impact of a keystone species is usually detected when the species is no longer present. For example, in tropical wet forests, if tigers are absent, more leopards occur. These two species kill different prey—leopards usually kill smaller and more diverse species—so the effects of this shift cascade through the entire community.

Finally, there is the concept of the indicator species. These are species whose presence or absence or a change in their distribution and abundance reflects changes in environmental quality or other measures. For example, changes in the time that some plants flower or that some mammals give birth in seasonal environments may reveal that the climate has changed. Some species are sensitive to habitat fragmentation, pollution, or other stressors that degrade biodiversity, and monitoring their population changes may alert scientists to those environmental changes. Population trends among fishing cats and flat-headed cats may indicate the quality of water and streamside habitat. Indicator species are useful in management and public relations because they can signal an increased need to protect water quality, which may gather more public support than a call to protect the species itself, although the latter may be accomplished at the same time.

The answer to this question is contained in this quote from Stephen R. Humphrey and Bradley M. Stith: “Conservation of species and undamaged habitat as a practice of human culture has developed like a three-legged stool. Each leg is necessary but not sufficient. The legs of the conservation stool are sustainable use of renewable resources, species recovery, and habitat preservation. Conservation can progress by focusing on each of these, defining their limits, developing improvements, and preventing dysfunction” (1990, 341).

This is a powerful statement, a vision that encompasses just about all we have to do. However, after working on wild cat conservation for three decades, we have articulated another formula, the Five Cs of Conservation: For carnivores to have a future, there must be core protected areas in the form of reserves, habitat corridors connecting the core areas, and the participation and support of human communities that affect and are affected by the cores and corridors, and to make it all work, there must be effective communication among local communities, their local supporters, and well wishers everywhere. This extends rather than replaces the formula of Humphrey and Stith.

The traditional approach to securing a future for endangered species prescribed a simple formula: protect a few pieces of nature by keeping people out; leave them undisturbed; the animals and their habitats will survive there indefinitely. Conservation biologists now believe that this approach represents hospice ecology: watching carefully and compassionately as species inevitably slip into extinction.

Ultimately, human values will determine whether we sustain landscapes with wild cat species intact. The troubles that wild cats have stem from human conflicts over values, over what matters most to people. People will almost always put their own needs and the needs of their families and communities first, so somehow the presence of wild cats must help, or at least not hinder, people’s ability to meet their own needs. To secure a future for wild cats, conservation actions must be adaptable, relevant, and made socially acceptable by linking the welfare of cats to that of people who live near them. A better future for all of us lies in establishing sustainable relationships between people and resources.

Legal protection and the establishment of protected areas have been cornerstones in programs to check declines and restore threatened and endangered wildlife, and such goals are accomplished only through tremendous effort by conservationists. Protected areas are important building blocks in wild cat conservation, but many wild cats live outside protected areas, move in and out of them, and must travel between them. Any formulation for the survival of wild cats has to include the protection of these individuals. Recognizing this, conservationists are searching for ways to partner with people living among wild cats, because they have the most to lose or gain.

In many areas, what can be accomplished through legal protection and reserve establishment seems to have reached a plateau, and we must find other ways to increase the population sizes of cat species of concern. These ways include securing and protecting larger reserves, protecting essential habitat outside reserves, incorporating the protection and habitat requirement of target species within land management systems surrounding reserves, and linking core reserves through connecting corridors.

Our best opportunities to increase the chances of survival for wild cat species are in those middle landscapes that lie between the urban and the wild. Because people are the dominant force driving what happens there, conservationists must engage these people in ways that turn this into a win-win situation for both them and the cats. This “local guardianship” concept is the key to securing the future for many wild cat species. We cannot simply proclaim that populations of many wild cats are at risk of extinction. As conservation people have said: No more prizes for predicting rain. Prizes only for building arks. We have to see a future for wild cats through restoration that improves living conditions for everyone. Wild cats can be stars in the ecological recovery that improves the lives of people who live near them.

In the mid-1970s, conservation practitioners tracking the wildlife trade noted that hundreds of thousands of wild cat skins were being shipped from source countries, mostly in the tropics, to user countries, mostly in western Europe and the United States. In large measure this was the impetus for CITES, the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna. If wild cat species, especially those with spotted or striped fur, were to survive, this trade would have to be restricted or, better, stopped. CITES became the legal instrument for curbing the fur trade, but the real muscle came from a concentrated awareness campaign conducted by many conservation organizations. This campaign targeted those who bought coats and other items made of these cat skins, including fashion leaders and celebrities, pointing out that they personally were dooming cats to extinction. By and large, this awareness campaign worked and essentially eliminated much of this threat to wild cats. More recently, the use of wild cats and other wildlife as medicine and food is sparking grave concern, and conservation organizations are again working to use awareness to curtail this. As yet no downward trend in consumption has occurred, but the program is just coming together. The fate of many wild cats lies in its success or failure.

The first thing you can do to help is to learn as much as you can about the conservation challenges facing the cat that you are particularly interested in. Reading this book has given you an overview of the conservation issues and the underlying biology of the cats upon which effective conservation actions must be based. Go to your local zoo and really watch the cats that live there. Compare them with each other. Ask zookeepers about the different species and individuals and their temperaments until you have more questions than they can answer. Seek answers to the remaining questions from other authorities and through extensive reading. Get to know the many conservation-minded nongovernment organizations (NGOs) that use cats as flagships. Find out just how each organization is addressing the conservation issues for the wild cat species that has caught your attention. Use your knowledge of wild cat biology and conservation issues to increase awareness among your family and friends.

One person can make a difference. Mark Baltz was a graduate student at the University of Missouri, Columbia, whose mascot is the Bengal tiger. He wrote an editorial for the local paper asking if the supporters of the University of Missouri should not also be interested in their mascot’s continued survival in the wild. This caught the attention of Chancellor Richard Wallace. He met Baltz, and out of that meeting “Mizzou for Tigers” was born, to raise awareness of the plight of wild tigers, to raise money for fellowships and faculty appointments, and to support wild tiger biology and conservation programs, all linked to the school’s Bengal tiger mascot. Hundreds of schools have chosen wild cats of one species or another as mascots, and similar actions there would be helpful to those cats.

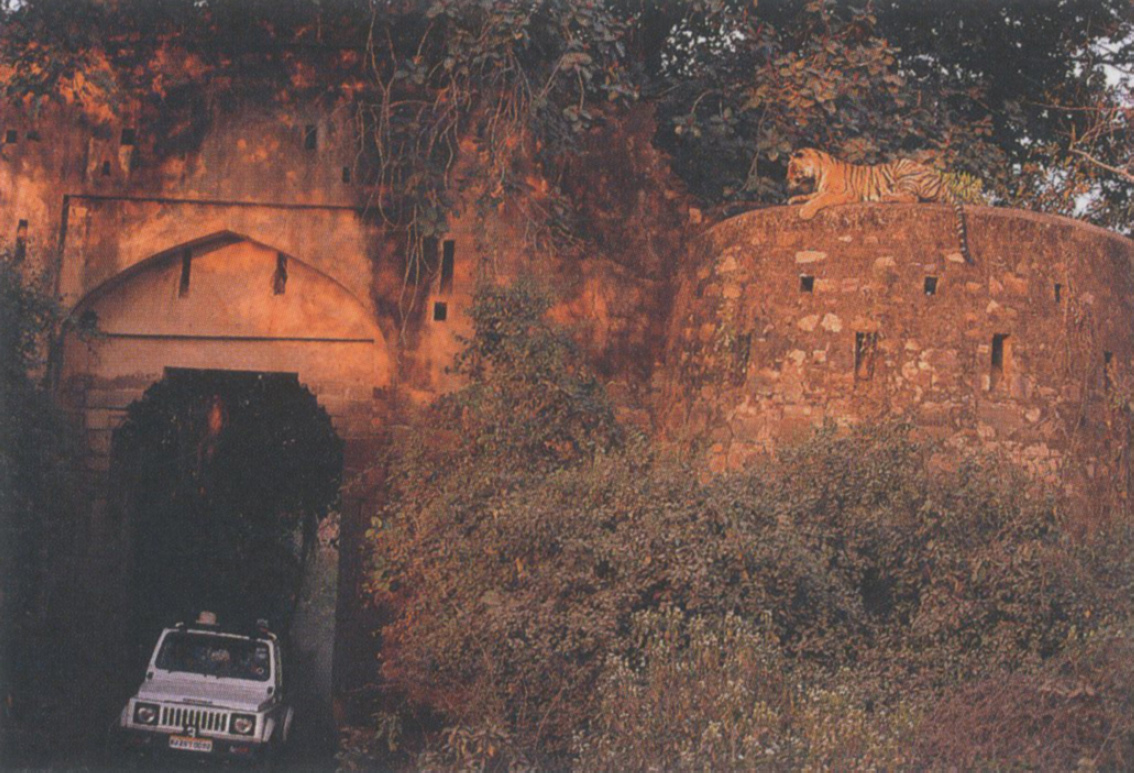

Income generation through ecotourism is one way to make the conservation of cats and other wildlife relevant and valuable to people who live near and among them. Everyone can support this, whether by taking an outing to a local national park or wildlife refuge or by traveling to India’s famed Ranthambore National Park, where tigers and tourists mingle among the ruins of an ancient fortress.

Conservation-minded NGOs are always looking for monetary and human resources. Contribute where you can, both in dollars and by volunteering. Wild cat biologists are always looking for help—for example, volunteers to help maintain our paper filing systems and enter data into our electronic databases.

Go see a wild cat. Be an ecotourist or join a study tour in which volunteers help a wild cat biologist in the field. Ecotourism and study tours add value to living wild cats because they bring attention and money to local economies. You may never see a wild cat because of their nature, but your interest makes their lives matter, and that is an enormous contribution. The inspiration for many wild cat biologists and conservation-minded NGOs is the declaration of anthropologist Margaret Mead: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”

Jared Diamond points out that “domesticable animals are all alike; every undomesticable animal is undomesticable in its own way” (1997, 157). In fact, wild cats possess many of the traits that have made other species undomesticable: They are solitary and territorial. They tend to have a nasty disposition. As carnivores, they don’t efficiently convert food biomass into meat for us to eat. And they often don’t breed well in captivity; surprisingly, most small wild cats breed relatively poorly in zoos.

Nonetheless, cats have been domesticated, or maybe not precisely. Diamond says domestication involves wild animals’ being transformed into something more useful to humans. If, however, cats’ primary use to us has been as killers of rodent pests, it would be difficult to imagine how we might have made a wildcat, already a supremely well specialized hunter of rats and mice, more useful. In fact, all that may have been necessary to begin the bond between people and cats was the proliferation of rodents around the granaries of the first farmers and some cats’ willingness to tolerate the proximity to people in exchange for access to abundant prey.

Perhaps as a result, there are few morphological differences between domestic cats and their most likely wild ancestor, the African subspecies of the wildcat. So when archaeologists find cat and human remains together, as they did in a Jericho (modern Israel) site dating to 7000–6000 BCE and in an Indus Valley site dating to about 2000 BCE, it’s not always clear whether the cats were domestics, or captives, or wildcats killed for fur or food.

The earliest clear sign of a familiar relationship between people and cats is a cat’s jawbone excavated from one of the earliest human settlements on Cyprus, about 8,000 years ago. Because no cats occurred naturally on this Mediterranean island, the colonists who first arrived by sea must have brought cats with them. Bones of mice are also found here, perhaps less welcome stowaways on boats and another reason to include cats onboard. But even here, the cats may merely have been wildcats captured as kittens and tamed, a practice people the world over have indulged in.

Taming wild cats was formalized with cheetahs and, to a lesser extent, caracals in historical times. In the Middle East and India, cheetahs were captured, tamed, and trained to hunt gazelles beginning about 1,000 years ago and continuing into this century. Caracals were trained to hunt hares and birds. But cheetahs failed to breed in captivity until the 1950s, and thus domestication was impossible.

Specialists generally agree that African wildcats must have been first domesticated in Egypt between 4,000 and 5,000 years ago. Cats begin to figure in Egyptian art about 2000 BCE, or 4,000 years ago, with one exceptional image of a cat wearing a collar dating to about 2600 BCE. By about 1600 BCE, domestic cats clearly and frequently appear in art, shown sitting under chairs, eating fish, playing, and helping people hunt birds in the Nile Delta’s papyrus swamps. From Egypt, domestic cats very slowly diffused throughout Europe and Asia.

African wildcats taking advantage of the rodents that thrived around human settlements in ancient Egypt gave rise to domestic cats that now live around the world. Scientists believe the cats were first domesticated between 4,000 and 5,000 years ago, but wildcats and people probably lived commensally for much longer.

The Egyptians tried to keep cats for themselves by making it illegal to export them to other countries. Their embargo seems to have been surprisingly effective, because there is little unequivocal evidence of domestic cats outside Egypt until 500 BCE in Greece, where a marble block depicts a leashed domestic cat squaring off with a leashed domestic dog. Earlier evidence of possibly domestic cats outside Egypt, including bone and foot prints dating back to 2500–2100 BCE from the Indus Valley’s Harrappa culture in what is now Pakistan and western India, may represent local domestication or captive wild cats. Harrappan feline figurines depict cats with collars, but other figurines with collars are of rhinos and other species that were captive, not domestic. An ivory statuette of a cat from 1700 BCE Palestine and a fresco and sculptured head of a cat from 1500 to 1100 BCE Crete are better evidence of domestic cats outside Egypt, because both countries had trade connections with Egypt, but the scarcity of cat artifacts suggests that domestic cats remained confined to their center of domestication for millennia. And even when they did begin to appear more often in Europe, they attracted little fanfare; also, it is likely that cats were not actively traded but rather largely moved themselves, in the words of Konrad Lorenz, “from house to house, from village to village, until they gradually took possession of the whole continent” (1988, 19). It has also been suggested that the movement and expansion of cats followed that of the black rat, which was native to Asia, the brown rat, native to eastern Asia, and the house mouse, from southern Europe and Asia. Cats moved from Greece to Italy in the fifth century BCE and spread with the Romans through Europe via imperial routes. Cats reached Britain by the fourth century CE and penetrated all of Europe and Asia by the tenth century. Surprisingly, cats weren’t known as ratters and mousers until the fourth century CE in Rome—both Greeks and Roman employed domestic polecats and ferrets for this purpose—and Romans didn’t even have a word to describe domestic cats specifically until then.

The movement of cats along established trade routes, including maritime routes, may owe more to human intervention than to their own agency. Cats were popular shipboard companions because they killed rodents and were considered good luck. Cats in this role reached islands and other far-flung parts of the world during the Age of Exploration, from the thirteenth through the eighteenth century, when Europeans sailed the world and began to settle in foreign lands. Few of even the most remote of uninhabited oceanic islands escaped colonization by domestic cats, which quickly went feral (see Why Are Feral Cats—and Pet Cats—Sometimes a Menace?). It is possible to show the genetic linkages between the domestic cats in various parts of the New World and the domestic cats in the countries from which the majority of European immigrants came. To this day, domestic cats in New England are fairly similar genetically, but the domestic cats of New York City stand out as distinctly different. Why? Because New York was first settled by the Dutch, whereas the rest of New England was settled by the English, and each group brought their own local cats with them.

Scientists can easily separate dogs from their wolf ancestors by genetic analysis, but the genetic differences between wildcats (Felis silvestris) and domestic cats (F. catus) are considered trivial and comparable to the differences seen among individuals within each of the two species. According to some authorities, the genetic evidence reveals that domestic cats are similar enough to both African and European wildcats to be called the same species; others disagree, maintaining the separation of the domestic cat from its wild ancestors. It is generally agreed on the basis of behavior, however, that domestic cats came from African wildcats. African wildcats are less fearful of people and less aggressive than their European counterparts, thus easier to tame. Today, African wildcats live near villages and show less fear of people than the far warier European wildcats.

Studies of red foxes reveal that selection for tameness and affection for people can turn a line of wild red foxes into doglike pets in a mere 20 years. Associated with this are other changes, including new coat color patterns, reproductive changes that resulted in their breeding all year around instead of once a year, and higher levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin, which has a calming effect. Prozac and other drugs prescribed for depression in people increase the levels of serotonin as well. Veterinarians treat domestic cats with behavioral problems related to anxiety with similar drugs that increase serotonin.

Ancient Egyptians mummified millions of cats as part of their devotions to the goddess Bastet, whom cats embodied. So common were these mummies that an English firm collected and pulverized an estimated 180,000 of them to sell as fertilizer in the late 1800s. (Photo by Chip Clarke)

Domestic cats similarly have diverse coat color patterns and may breed year around, whereas wildcats are believed to be seasonal breeders. Certain coat colors in domestic cats are associated with different temperaments. The most common coat colors today are blotched tabby, black, and orange, all colors correlated with calmer cats than the agouti or striped tabby, which have the ancestral coat colors. Domestic cats also tend to have proportionately smaller brains, jaws, and teeth, shorter legs, and longer digestive tracts than wildcats.

An interesting difference was recently discovered between domestic dogs and wolves. Both dogs and wolves equally socialized to people could find hidden food by following clues from a familiar person, such as touching or pointing to the food’s location, but wolves were not as good as dogs. The two were also trained to solve a problem and then given an insoluble variation of the problem. Dogs turned and looked at the familiar person, as if to ask for direction; wolves did not, suggesting that dogs have evolved to communicate with people. People who have raised wildcats and individuals of other small wild cat species say that they are not afraid of people but simply indifferent to them. Wild cats in zoos ignore visitors, acting as if they aren’t there at all. It would be interesting to conduct similar scientific studies to learn if domestic cats are any better at reading human signals or are more likely to look to people to solve a problem than tamed wildcats or other wild cats are.

Feral cats are free-ranging domestic cats that live outside of human control. In essence, these are domesticated cats gone wild again, something cats appear to do quite readily. Feral cats occupy diverse natural habitats, from the alleys of large urban areas, to farmlands, to remote oceanic islands where people no longer live or may never have been in permanent residence. They live in the cold temperatures of subantarctic islands and in the tropics. Also, their densities vary, for example, from about 1 per square kilometer in Australian grasslands to about 2,000 per square kilometer in the small fishing village of Ainoshima in Japan.

Discarded human food and other garbage form a large portion of feral cats’ diet in urban areas where prey other than Norway and black rats, house mice (which are also attracted to human garbage), and various birds are scarce. Indeed, the line between feral and other domestic cats in urban areas is often indistinct, with some house cats left to fend more or less for themselves and some feral cats fed by people who don’t take care of them in other ways.

On islands with no indigenous mammals, the primary prey of the introduced cats are other introduced species, including Norway and black rats, house mice, and European rabbits. On oceanic islands, seabirds that nest in large colonies are another source of food for feral cats. Elsewhere, feral cats, like the ancestral wildcats, are primarily predators of small mammals, from mice and voles to small (or young) rabbits and hares; compared with mammals, birds are a relatively small part of their diet in most places, and reptiles are taken only infrequently.

In some situations, feral cats live in well-organized social groups that are somewhat similar to, but more variable than, those of lions. For all animal species, variation in the distribution, predictability, and abundance of resources—food, water, shelter, nest sites, and mates—influences social organization. For most wild cats and many feral cat populations, food (prey) is widely dispersed and unpredictably found, which results in their typically solitary life style. But where food is abundant and can be found in predictable patches, feral cats live in groups to take advantage of the largesse. These patches are generally associated with human activities, such as farms or garbage dumps.

Domestic cats gone wild, feral cats often form social groups similar to those of lions, something their wildcat ancestors are never observed to do. Few places on Earth are without feral cats, which can reach astonishing densities where food discarded by people is abundant.

The ability of feral cats to live in groups may, however, be an effect of domestication, because domestic cats have no doubt been bred to tolerate the proximity of companions, including people and other domestic animals. A study of African wildcats and feral cats sharing an area in Saudi Arabia revealed that feral cats formed a colony to use the clumped food resources of a dump, but the wildcats maintained their solitary existence.

Even with domestication, cats have lost none of their predatory instincts. Predation by feral cats has a significant effect on the numbers of rodents (rats and mice), lagomorphs (rabbits and hares), and birds in an area. Their strongest effect has been observed on islands but is felt on continents as well. The Global Invasive Species Specialist Group includes domestics cats on its list, 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species, noting that only habitat loss is a greater cause of species endangerment and extinction. Cats are believed responsible for, or at least involved in, the extinction of more bird species than anything else except habitat destruction.

One striking example shows how even a single cat’s introduction to an island previously cat-free can wreak havoc. In 1894, David Lyall became the lighthouse keeper on a small, uninhabited island off New Zealand. He brought with him a cat. Among the cat’s prey were unique flightless wrens, later named Stephens Island wrens. In typical cat fashion, the animal presented 17 of the birds to Lyall. These proved to be a species previously unknown to science—and remain the only specimens of this species anywhere. Within a year of Lyall and his cat’s arrival, the wren was extinct. Unable to fly, the birds were easy pickings, and a single cat made short work of eating the species to extinction.

While not quite so dramatic, similar scenarios have played out elsewhere. On a subantarctic island chain called the Crozet Islands, cats extirpated 10 species of petrels, pelagic seabirds that nest on the ground on islands. In a fairly typical pattern, sealing ships accidentally brought rats and mice, and cats were then imported to control the rodents; rabbits were introduced to provide food for sailors, but they also provided food for cats, enabling the cat population to grow.

Bradford Keitt and his colleagues (2002) looked at the impact of feral cats on the black-vented shearwater, which is a bird endemic to the Pacific islands off the Baja California peninsula. About 95 percent of the world’s population of this species lives on Natividad Island, along with a small number of cats. Estimating that each cat would eat about 45 shearwaters a month to fill its nutritional requirements, these scientists predicted that 20 cats could eliminate a population of 150,000 shearwaters, the size of the Natividad Island population in 1997, in less than 25 years. Fortunately, 25 cats—believed to be all the cats on the island—were removed after Keitt’s study, before it was too late. Several subspecies endemic to these islands, however, had already been driven to extinction by feral cats.

Domestic cats arrived in North America with European colonists less than 500 years ago. Today, an estimated 70 million pet cats live in the United States, and another 40 million or so free-ranging, or feral, cats live in urban, suburban, and rural habitats. The number of small mammals and birds these cats eat is staggering: more than a billion are taken each year by rural cats alone! These cats do us a service in eating rats and mice that are pests, but they also take songbirds—by one estimate about 39 million birds are killed each year in Wisconsin alone—many of which are in decline because of habitat loss in North America as well as in Central and South America, where many of these birds winter. Cats are also implicated in the decline of least terns, piping plovers, and loggerhead shrikes.

A 2003 study in Florida revealed a host of species actually or potentially affected by pet and feral cats. For instance, the entire population of the endangered Florida Keys marsh rabbit is 100 to 300 individuals. Annually, some 53 percent of the deaths of this species are attributed to feral cats, and experts predict the species may be extinct within 20 or 30 years.

Predation is not the only problem that feral and pet domestic cats pose. Their potential to spread disease to wild animals as well as to people is also an issue (see Do Cats Get Sick?). Cats can spread rabies, feline panleukopenia (distemper), and FIV, feline immunodeficiency virus, which is similar to the human HIV. Pumas are known to have caught feline leukemia from domestic cats, and the critically endangered Florida panther subspecies may have been infected with distemper and FIV. In Israel, wildcats may be rare thanks to feline panleukopenia, which is spread by domestic cats there.

In 2003, scientists linked a parasite carried by domestic cats, Toxoplasma gondii, to many deaths of California sea otters from 1989 to 2001, when the population dropped by about 10 percent. The parasite is found in cat feces, and scientists speculate that runoff from the feces of feral cats and from flushable cat litter has transported the parasite to the ocean, exposing sea otters to it. Pregnant women who suffer toxoplasmosis as a result of infection with T. gondii may give birth to children with severe physical abnormalities.

Domestic cats have been implicated in transmitting bubonic plague to people in the United States, especially in Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico, where suburbs are springing up near once-remote areas in which the disease is endemic in wild rodents. Domestic cats that roam freely in these areas are at increased risk for infection and, therefore, increase the risk for transmission to humans. Before 1977, domestic cats were not reported as sources of human plague infection; since then, domestic cats have been the source of infection in 15 human plague cases.

Feral cats also compete with native predators, such as raptors and other mammalian carnivores that depend on small mammals and birds for sustenance. One study estimates that cats are far more abundant than all the other medium-sized carnivores, or “mesocarnivores,” combined in some rural Wisconsin areas. This must have an impact on the food available to foxes, raccoons, skunks, and other predators of this size.

In Europe, Asia, and Africa, domestic cats threaten their wildcat relative because they readily hybridize, and it is feared that domestic cat genes will swamp those of wildcats. In southern Africa, all wildcats living close to human settlements with domestic cats are hybrids, but hybrids have also been reported in more remote areas. Overall, the Cat Specialist Group believes this to be the greatest threat to the African wildcat. Scottish wildcats are also mostly hybrids, and Asiatic wildcat hybrids are reported from Pakistan and central Asia and probably occur elsewhere in Asia. This threat to wild cats may be greater than is known. Domestic cat fanciers have successfully mated domestic cats with rusty-spotted cats, Asian jungle cats, Geoffroy’s cats, and other wild species to produce novelty breeds. Whether interbreeding occurs naturally where these wild species range near people is not known.

Both feral and pet domestic cats pose threats to populations of wild cats as well as to a host of other species. In Scotland, interbreeding between domestic cats and native Scottish wildcats (above) means that many, if not most, of the animals called wildcats there are actually hybrids. Similar hybrids appear even in remote areas of Africa and perhaps Asia as well.

For most of the history of domestic cats, there were no breeds, or at least none deliberately created. Unlike dogs, which people had long selectively bred to perform diverse useful tasks, from guarding sheep to hunting rabbits and pulling sleds, cats were left to be cats. Over time, differences emerged among the domestic cats predominant in various parts of world, thanks to the founder effect, in which the particular cats that reached an area were by chance somewhat genetically distinct from others in the general population. In addition, isolated populations adapted to local conditions through natural selection. From time to time, people may also have exerted some selection for novel or attractive fur color.

It wasn’t until the middle of the nineteenth century in England that cat fanciers began to show cats and thus took an interest in selectively breeding them for particular qualities and importing exotic cats from afar. But even then, selection was for appearance and, later, temperament, not for functional attributes. The first-ever cat show was held in 1871 at the Crystal Palace in London, and now there are various associations of cat fanciers around the world. The Cat Fanciers Association, billed as the largest registry of pedigreed cats, recognizes 41 breeds; the American Cat Fanciers Association lists 46 breeds; and the International Cat Association counts 47. Desmond Morris (1996) describes some 80 breeds. The fact is, cat breeders work to create new breeds all the time.

In the mid-1800s, British cat fanciers divided domestic cats into two sorts: the British (also called American or European) and the Foreign. The British cats are cold-adapted robust, stocky animals with large heads, short ears, and thick fur; they resemble the Scottish wildcats, with which they interbreed. In contrast, the Foreign cats are a hot-climate form, with slender bodies, long legs, large ears, and short fur; they most resemble the African wildcat. In addition, domestic cats are divided into short-haired and long-haired types, with the Persian cat being an exemplar of the latter. The origins of the long-haired Persians are obscure, but this breed is believed to have arisen in Persia (modern Iran), just as long-haired Angoras originated in nearby Turkey. In any case, today’s breeds are almost entirely the result of crossing British and Foreign cats and short-haired and long-haired cats, with additional selection for coat color, a fairly labile trait in all felids. A few breeds are the result of chance genetic mutations that breeders then selected for. For instance, the hairless Sphynx originated with a hairless kitten born in 1966, and LaPerms, which have curly fur, originated from a kitten born in 1982. A few others have their origins in recent crosses with wild cats. The Bengal, for instance, may have sprung from mating a domestic cat with a leopard cat.

Place-names attached to breeds may or may not reflect their geographic origins. Those that do are the names of many old breeds of cats that apparently emerged before cat fanciers began their experiments, including the Siamese, the Burmese, the tailless Manx from the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea, the Persian and Angora, as noted above, and perhaps the Abyssinian, from modern-day Ethiopia, a cat some believe to be descended from the first domestic cats of Egypt. In contrast, the Russian Blue may be called that only because the first of this sort to reach Britain came from Archangel, a Russian port. The Kashmir cat was created in North America, and Morris reports that “the name is based on the fact that this breed is close to the Himalayan breed and Kashmir is close to the Himalayas” (1996, 244). The Himalayan cat isn’t from the Himalayas either; it is a cross between Persian and Siamese cats.

While these pedigreed cats owe their modern appearance primarily to human intervention, variations in coat color, in particular, appear to have ancient origins. The ancestral coloration of domestic cats is that of the African wildcat: striped or mackerel tabby. But black, blue, orange, white-spotted, and white cats are found worldwide, suggesting that this diversity was present when cats first began to leave Egypt.

In her 1998 book, called The Cat and the Human Imagination, Katherine M. Rogers wrote:

Although it may seem obvious to us today that cats are peculiarly suited to supernatural roles, this attitude is largely a product of nineteenth- and twentieth-century sensibilities. The main reason cats were persecuted is the prosaic one that they were abundant and considered valueless. When animals were to be sacrificed as scapegoats to allay public guilt or anxiety, as placatory offerings to ensure a good harvest or a stable building, or as exciting special effects in spectacles and processions, the obvious course was to round up the local cats. (p. 46)

Forty to 80 breeds of domestic cats have been named, but the range of variation among cat breeds is much smaller than that among dog breeds. Domestic cats all fall within a small range of sizes, and no breed shows the extreme morphological or behavioral features that occur in some dog breeds. There are no cat equivalents of tiny Chihuahuas or massive Saint Bernards, for instance. Most variation among domestic cats is in fur color, pattern, and length. Persian cats, with their very long fur and stocky bodies, belong to an old breed that was developed in Persia (modern-day Iran) by the seventeenth century (Eric Isselee/Shutterstock.com). The breed known as Russian Blue is short-haired and tabby, with its markings masked by dense bluish-gray fur; its angular body reveals the recent introduction of Siamese cat genes into the breed (Utekhina Anna/Shutterstock.com). The first domestic cats were tabby, but only lightly striped and spotted. The blotched tabby, with its strong markings and short hair, displays a common fur configuration of domestic cats today. This form probably first appeared in Britain about 400 years ago and spread from there across the globe with the growth of the British Empire (Deamles for sale/Shutterstock.com). The freakish hairless Sphynx is a product of the twentieth century (Eric Isselee/Shutterstock.com).

Although we think of black cats and witches as natural companions, Rogers points out that it wasn’t always so. Witches were believed to turn themselves into a variety animals when conducting evil deeds or to have an animal companion, “a familiar,” that carried out their mischief. In England, for instance, the original witch’s familiar was a hare, associated with Eostre, a pagan fertility goddess. Like cats, hares are nocturnal, elusive creatures; like hares, cats were pagan symbols of female fertility and sexuality. This last may help account for singling out cats for opprobrium. The early Catholic Church ruthlessly sought to eliminate vestiges of pagan belief, and it also condemned the female sexuality that cats symbolize. Furthermore, affection for a cat was in itself suspect. Cats’ aloof indifference to people, their refusal to recognize people as masters, violated the natural order: God gave people dominion over animals, and thus cats, with their secretive ways, must be on the side of Satan.

From the twelfth through the fourteenth century, the Church accused heretics of worshipping Satan in the guise of a large black cat, and, later, witches were accused of flying to their nocturnal meetings on the backs of large black cats. But during the heyday of European witch persecution, in the 1500s and 1600s, legal records show that a woman might be accused of witchcraft if she associated with cats of any color, as well as with dogs, mice, toads, lambs, rabbits, and polecats. Rogers writes: “Any animal would do if it were small—because of the physical intimacy between witch and familiar—and cheap. Accused witches were usually too poor to own highbred pets, and it was considerably safer to accuse a poor woman’s cat of being an agent of Satan than to accuse the squire’s prize greyhound” (1998, 52). Cats became typecast in the role of witch’s companion only when witchcraft became the stuff of literature, and writers found cats more attractive as familiars than other small animals. By the 1800s, when belief in witchcraft was largely a thing of the past, witches and their cats began to acquire an exotic allure.

Before this shift occurred, attitudes toward cats remained mostly negative. For centuries, cats were the pets of the poor: compared with dogs, they required no extra feeding and demanded no special care. Although both animals were useful to people, dogs were admired for their subservience to humans, while cats were disliked for their lack of it. Depicted in paintings, cats represented greed and a threat to domesticity. Cats were casually persecuted and tortured with shocking indifference, both officially (they were burned alive inside an effigy of the pope during Elizabeth I’s coronation) and at the hands of small boys who might fling them from windows or tie two together by the tails in order to watch them fight. Even influential naturalists reviled cats. In 1607, Edward Topsell’s The History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents and Insects painted cats as dangerous beasts with venomous teeth and poisonous flesh that caused illness and joined in branding cats as familiars of witches (cited in Rogers 1998).

The Romantic movement, which began in the 1700s, changed all that. Romantics glorified wild, untamed nature, and suddenly the cat became the dog’s superior. Dogs were denigrated for their servility; cats were celebrated for their insistence on freedom. Cats “could not be fully appreciated as companions until their wildness was perceived as attractive rather than obstinately perverse,” says Rogers (1998, 189). A greater appreciation for cats finally led to the creation of breeding societies in the late 1800s, when, for the first time, cats were valued enough to be shown by the wealthy and bred for desirable and attractive traits.

While purported witches did not confine themselves to black cats, black cats did epitomize feline evil, their color alone representing the forces of darkness. Black cats have signified bad luck for centuries, and even today, superstitious Americans consider a black cat crossing their path as bad luck. In Britain, however, this is a sign of good luck, based on the idea that evil has passed you by. And in many other contexts, such as on ships and backstage at a theater, cats are good luck; a cat on stage, however, is bad luck. Superstitions arise when some event is coincidentally associated with another one several times, and people mistake the coincidence for cause and effect. Given the abundance of cats, it’s not surprising that both good fortune and misfortune might often befall people while in the presence of cats.

Other superstitions about cats relate to their effect on human health. Cats were once believed to cause rheumatism and tuberculosis. People still believe that cats suffocate babies or suck their breath. These beliefs may have some basis in many people’s allergic reaction to cats, or, more specifically, to a protein called fel d 1, found in cats’ saliva and sebaceous glands. When a cat grooms itself, its hair and skin become coated with this protein, which is then shed as dander and inhaled by anyone in that environment. The airborne protein triggers an immune response in susceptible people. The allergic reaction varies from irritating itchy eyes and runny nose to life-threatening asthma attacks. Cat allergies are common around the world; in the United States, 5 to 10 percent of the population experiences an allergic reaction to cats, and a major study found that 30 percent of laboratory staff working with cats develop allergies. A recent study, however, suggests that not all cats are equally allergenic. Scientists studied 312 patients who reported severe allergy symptoms, moderate symptoms, mild symptoms, or no symptoms. Subjects with dark-colored cats were two to four times more likely to report severe or moderate symptoms than those with light-colored or no cats. There was no difference in the severity of the symptoms between those with light cats and those with no cats. The scientists speculate that black cats may produce more of the fel d 1 allergen than others. Thus, for people susceptible to allergies, black cats may indeed be unlucky.

Finally, many superstitions about cats relate to the idea that cats can predict the weather. For instance, to some, a cat washing its face predicts good weather or is a sign of rain, and so is a cat sneezing or scratching a table leg. When a cat’s routine behavior predicts both good and bad weather (or good and back luck), it is bound to be correct half the time, a good basis for the development of superstitions. Some speculate, however, that cats’ sensitivity to vibrations and to sounds beyond our hearing enables them to detect coming storms or earthquakes. This hypothesis is attractive until you consider the number of other animals believed to be able to predict the weather. For instance, a whistling parrot, a hooting owl, a quacking duck, a sitting cow, and a noisy sparrow are all thought to predict rain.

People who admire large cats and worry about their future don’t like to think of them as enemies. But big cats do kill people. Resolving this conflict and devising a coexistence recipe are essential if large cats are to survive in our human-dominated world. On the other hand, it is probably good for us to lay our hubris aside and think of ourselves as just another meal from time to time, because it helps us to understand our world more comprehensively as well as our place in it.

Tigers, lions, leopards, pumas, and jaguars sometimes kill people. Cheetahs, snow leopards, and clouded leopards have never been reported to do so. Cases of tigers killing humans come from almost all parts of their range in Asia. (The term “man”-killer is traditional, although perhaps even more women than men are killed by large cats. Also, in some historical traditions a man-killer was not recorded and the big cat was not labeled as a man-eater until a number of victims—three or more in some places—had been killed.)

Cases of lions killing people come from nearly their entire range in Africa. The Asian lion was not known for man killing, but recently several cases have been reported in the Indian state of Gujarat, where the last Asian lions live. Leopards are known to kill people throughout most of their range in Africa and Asia but, under most circumstances, less often historically than lions and tigers have killed. Recently, with the tiger in decline in many places it formerly lived, leopard numbers have increased, and so have human deaths attributed to leopards in those areas. This has been particularly troublesome in Nepal and northern India.

Biologist Paul Beier searched all the records he could find from 1890 to 1990 for incidents of puma attacks on people, and he was able to document 9 fatal attacks and 44 nonfatal attacks resulting in 10 human deaths and 48 nonfatal injuries (two victims were involved in each of five different attacks). Between 1991 and 2003, more puma attacks on people occurred, several of them fatal. There are very few records of jaguars attacking people. Kevin Seymore concluded in a major review that “the jaguar is least likely of any of the pantherines to attack man and is virtually undocumented as a maneater” (1989, 5). Biologists Rafael Hoogesteijn and Edgardo Mondolfi have extensive experience with this large cat and conclude much the same: “Although there are numerous cases of attacks on man, the overwhelming majority are due to hunting accidents in which the feline was wounded or cornered by dogs” (1993, 88).

The most comprehensive account of man killing by tigers and leopards is by environmental historian Peter Boomgaard. In Frontiers of Fear: Tigers and People in the Malay World, 1600–1950 (2001), he compares man killing by these two large cats in India and the “Malay world,” which, for his purposes, includes peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, and Bali. Tigers but not leopards have occurred on the islands of Sumatra and Bali, but both have occurred on Java and peninsular Malaysia and in India. His sources were Dutch and British colonial records. His findings for the years 1882 to 1904 are astonishing. In India, an annual average of 889 deaths were attributed to tigers, and 317 to leopards, for a total annual average of 1,206. In Sumatra and Java, respectively, 58 and 51 annual deaths occurred during this period. Using 1875 as a benchmark, Boomgaard reported that for every million people, there were 66 deaths by tigers and leopards combined in India, 54.5 deaths by tigers in Sumatra, and 6.1 deaths by leopards and tigers combined in Java. Annually from 1860 to 1900, about 5,000 tigers and leopards were killed in India; 400 tigers and clouded leopards in Sumatra; and between 1,400 and 1,496 tigers and leopards in Java. Today, by official estimates, fewer than 3,000 wild tigers live in India, fewer than 500 tigers in Sumatra, and the tiger is now extinct on Java and Bali.

The determined approach of a huge lion would terrify anyone who stood in its path. Lions, tigers, and a few other big cats do sometimes kill people and have done so throughout our shared history. Man-eating cats, which specialize in preying on people, are rare, however. Most of the tragic human deaths caused by big cats result from chance encounters that provoke a cat to attack.

Although the British began their settlement of the island of Singapore in 1819, they reported no problems from tigers until they began clearing the island for plantations of peppers and other crops. By 1850, it was purported that one laborer a day was killed by tigers. There are no tigers on Singapore today. The British began to expand their colonization of the Malay Peninsula later, and records from there are not very useful. Livestock are reportedly killed each year by tigers in Malaysia, but human deaths rarely have been reported. In the last decade, people have been killed by tigers in Nepal, India, Bangladesh, Sumatra, and the Russian Far East.

The more we know about the behavioral ecology of large cats and why some become man-killers, the more remarkable it seems that attacks do not occur more often than they do, especially given the large number of people who are sharing landscapes with large cats. But there are more ideas about why some large cats kill people than why others do not.

We don’t know how many attacks on people occur because the cat has the furious form of rabies, although at least some are likely to stem from this. Large cats may kill people simply because their prey have been depleted and they are hungry. Or, the cat may be hungry because it is incapacitated or compromised by an injury and is unable to kill its normal prey. Or, the cat may be socially subordinate and pushed into marginal hunting areas by dominant cats. Or, these subordinate cats may hunt during the day, increasing the odds of meeting a person out and about. Young cats in the process of learning how to hunt often go after prey that an experienced cat would not. For example, cheetahs with no actual hunting experience stalk and rush at objects as diverse as policemen on motorbikes, Grevy’s zebras, and yellow school buses at the National Zoo.

In other cases, a large cat may hunt livestock or dogs around people’s dwellings or farmsteads and have a fateful encounter with someone who steps outside. John once investigated an incident in India in which a tiger killed a woman who had gone out at night to relieve herself. The tiger was probably after goats tied under her porch, and it was just bad luck that she appeared at the same time. The tiger had dispersed from the forest and was essentially trapped among some villages and shrimp ponds in the Sundarbans, the mangrove forest at the mouth of the Ganges in India and Bangladesh.