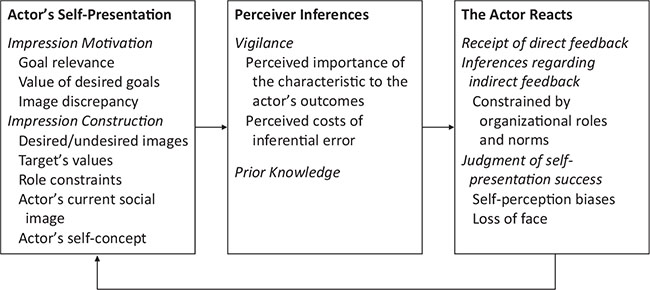

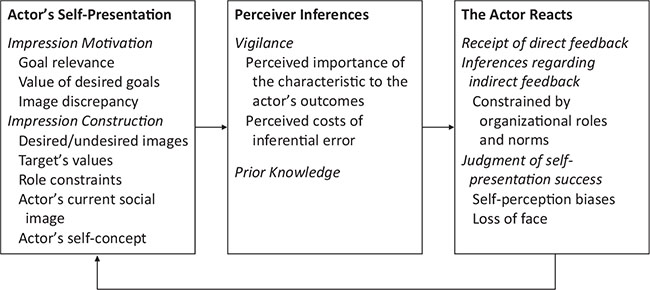

FIGURE 11.1 An Actor–Perceiver Model of Impression Management in Organizations

p.253

AN ACTOR–PERCEIVER MODEL OF IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT IN ORGANIZATIONS

Mark R. Leary and Mark C. Bolino

Many important outcomes in life are affected by the impressions that people have of one another, with implications for friendship development, romantic relationships, membership in groups, academic grades, leadership effectiveness, jury decisions, and sexual opportunities, to name just a few (Leary, 1995). In organizational settings, the impressions that people make of superiors, colleagues, and subordinates can influence people’s employment opportunities, job effectiveness, career advancement, status, attainment of leadership positions, and influence within the organization (Bolino, Kacmar, Turnley, & Gilstrap, 2008). Not surprisingly, then, people are attuned to the impressions that others have of them, try to control those impressions in ways that promote their goals, and take steps to repair the inevitable damage that occasionally occurs to their image at work. Well-executed impression management helps people to project the “right” images in their personal and professional lives (Bolino, Long, & Turnley, 2016), so it is beneficial for them to have some understanding of the dynamics of impression management and of how to manage their impressions more successfully. As Adam Grant (2016) wrote in the New York Times, the common admonition to “be yourself” is often “terrible” advice.

Theory and research on impression management within social psychology and organizational behavior have developed along two rather independent paths. Although theorists and researchers sometimes cite key contributions in the other domain, the areas have developed in parallel and few efforts have been made to integrate them (but see Bolino et al., 2008; Bolino et al., 2016; Giacalone & Rosenfeld, 1991; Rosenfeld, Giacalone, & Riordan, 1995). Both fields trace their beginnings to Goffman’s (1959) seminal book, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. From there, social psychologists turned primarily to laboratory studies that examined the situational influences on self-presentation and personality moderators of these effects, as well as the role of self-presentational processes in other phenomena, such as cognitive dissonance, social anxiety, eating, health behaviors, and the impostor phenomenon. After a surge of interest in the 1960s and 1970s (for reviews, see Baumeister, 1982; Leary, 1995; Leary & Kowalski, 1990; Schlenker, 1980, 2012), the topic took a back seat within social and personality psychology, possibly because the standard paradigms for studying self-presentation do not adequately capture the power and reach of self-presentational concerns outside of the laboratory (Leary, Allen, & Terry, 2011). Even so, steady progress continues to be made (see Schlenker, 2012).

p.254

Within organizational behavior and management, interest in impression management in organizations increased in the 1980s and early 1990s, when a number of conceptual papers, reviews, and book chapters were published on the topic (e.g., Gardner & Martinko, 1988; Giacalone & Rosenfeld, 1990, 1991; Tedeschi & Melburg, 1984). Research on impression management gained further momentum when Wayne and Ferris (1990) developed a measure of impression management and researchers became interested in the effects of impression management on performance appraisals, interviewer evaluations, and career outcomes (e.g., Ferris, Judge, Rowland, & Fitzgibbons, 1994; Judge & Bretz, 1994; Wayne & Liden, 1995). This line of work identified key impression management tactics and demonstrated their implications for important outcomes at work, including hiring decisions, performance evaluations, and promotions. Researchers also increasingly recognized that impression management motives and image concerns affect a variety of organizational behaviors, such as seeking feedback (Morrison & Bies, 1991) and going the extra mile (Bolino, 1999). More recently, impression management has also garnered attention from scholars of entrepreneurship and strategic management. For example, Parhankangas and Ehrlich (2014) examined how entrepreneurs use impression management strategies to attract funding from angel investors, and several studies have looked at the implications of CEO ingratiation (e.g., Westphal, 1998; Westphal & Deephouse, 2011).

Our goal in this chapter is to examine the nature of impression management in organizational settings, drawing upon and integrating the literatures in both social psychology and organizational behavior. We also aim to broaden the study of impression management by focusing on the dynamic interplay between actors and observers in the self-presentational aspects of organizational behavior.

The Nature of Impression Management

As we use the term, impression management (or self-presentation1) refers to behaviors that are enacted with the goal of influencing how others perceive the individual. Although most behaviors have the potential to influence other people’s perceptions of a person, behavior is considered to be impression management only if it has the goal of shaping how one is seen by others (Schlenker, 2012). For instance, employees may be helpful at work out of genuine concern for the organization’s effectiveness or because they believe that doing so will enhance their image as a dedicated employee. Only the latter case would be considered impression management; the former would be considered an example of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) (Bolino, 1999).

p.255

Many behaviors are enacted primarily for tangibly instrumental reasons with little or no attention paid to their self-presentational implications. For example, going to the office mail room has little connection to people’s self-presentational goals. Yet, people sometimes engage in behaviors with the goal of conveying a desired impression (or not conveying an undesired impression), and the instrumental function of the behavior, if there is one, is secondary. And, whatever else they may be doing, people generally keep an eye on the implications of their actions for their social images to avoid behaving in ways that might convey undesired impressions to other people. Thus, self-presentational motives exert a pervasive influence on behavior, and this influence is particularly intense in organizations where employees are often evaluated, either formally or informally, by supervisors, subordinates, peers, clients, and customers (Latham, Almost, Mann, & Moore, 2005).

In general, the self-presentations that help people achieve their goals – whether in organizations or in other areas of life – involve socially desirable images of the person (see also the Ferris & Sedikides chapter on self-enhancement in this volume). However, certain goals are better achieved via impressions that others view negatively. For example, people can avoid onerous tasks by appearing to be incompetent at them, supervisors can exert influence by appearing intolerant and hostile, and negotiators can gain the upper hand by appearing to be erratic and unpredictable (Becker & Martin, 1995; Kowalski & Leary, 1990). Yet, despite the occasional advantages of conveying undesirable impressions, trying to be seen as incompetent, intimidating, or unstable in organizational contexts can be risky (Bolino et al., 2016; Turnley & Bolino, 2001).

Contrary to common conceptions, impression management is not necessarily deceptive. Although people sometimes convey impressions of themselves that they know are not accurate, they often manage their impressions to be certain that other people are aware of their actual characteristics. Many desirable characteristics are not immediately observable by others, so individuals sometimes take deliberate steps to ensure that they are seen as desired. Thus, employees who use OCB and exemplification tactics of impression management (e.g., making their boss aware that they were working at the office over the weekend) to be seen as dedicated may, in fact, be truly dedicated, hard-working employees (Bolino, 1999). Indeed, when people present themselves honestly, others’ perceptions of them are more accurate (Murphy, 2007).

Most research on self-presentation has involved managing impressions of relatively stable attributes, such as one’s abilities, knowledge, personality characteristics, or attitudes. For example, in a job interview, applicants want to convey that they have the requisite knowledge, skills, and abilities for the job and that they share the organization’s values (Barrick, Shaffer, & DeGrassi, 2009; Roulin, Bangerter, & Levashina, 2015). However, people also manage impressions of their momentary states, as when people want to convey that they are displeased with another person’s performance or that they agree with another person’s suggestion. In such cases, people not only have a particular reaction but may also have the goal of showing others that they have the reaction, making the expression self-presentational.

p.256

Tactics

Virtually any behavior can be employed in the service of conveying impressions of oneself to others. The most direct self-presentational tactics involve verbal expressions – whether oral or written – that explicitly convey information about one’s personality, abilities, background, likes and dislikes, accomplishments, education, roles, and so on. Although verbal self-presentations often occur in face-to-face encounters, people also present themselves in writing, such as through letters, emails, resumes, personal ads, and postings to social media sites.

Virtually all theory and research have dealt with the ways in which people convey information about themselves, but people sometimes manage their impressions by withholding information – by not mentioning that they possess a particular trait, had a particular experience, or hold a particular attitude (Ellemers & Barreto, 2006). People also manage their impressions through their facial expressions, body position, direction of attention, gestures, and other nonverbal behavior – and by controlling spontaneous nonverbal behaviors that might convey an undesired impression. For example, people sometimes express, conceal, exaggerate, or fake their emotional reactions nonverbally. Unlike emotion regulation, which is used to manage one’s subjective feelings, impression management is employed to manage the emotions one appears to be feeling.

The material that people post about themselves online, including photos and videos, are also selected in part to convey desired impressions of themselves. The use of social media to manage impressions can be risky because online self-presentations usually cannot be targeted to specific audiences as in face-to-face interactions, raising the possibility that posts that make a desired impression on some observers make negative impressions on others. A study of college students found that while students who sought to project an image that they were hard-working typically posted appropriate content, those who wanted to project an image of being sexually appealing, wild, or offensive tended to post inappropriate content that could harm their chances of landing a job (Peluchette & Karl, 2009). Research also suggests that photographs posted online may influence targets’ impressions of an individual more strongly than verbal descriptions do (Van Der Heide, D’Angelo, & Schumaker, 2012). Many job applicants and employees may have realized this fact only after it was too late to remove their photographs from social media sites.

p.257

People also use physical objects to convey information about themselves, much as theatrical props are used in plays (Schlenker, 1980). For example, people’s choices of clothing and bodily adornment (such as jewelry, make-up, or tattoos) may be selected to convey a particular impression in a particular context, and much has been made of dressing for success. How people decorate their homes and offices – and the props that they display – are partly selected for their self-presentational impact. Indeed, in many offices, it is customary to provide evidence of one’s qualifications (e.g., diplomas, certificates) in order to project an image of competence (Elsbach, 2004). People also hide possessions from public view that might convey undesired impressions and exhibit those that are consonant with the image that they wish others to have of them (Goffman, 1959; Gosling, Ko, Mannarelli, & Morris, 2002).

People also influence others’ impressions by touting and hiding their connections with certain people and groups. For example, people sometimes tout their connections with those who are known to be successful, powerful, attractive, popular, or simply interesting and distance themselves from undesirable others (Cialdini, Borden, Thorne, Walker, Freeman, & Sloan, 1976; Snyder, Lassegard, & Ford, 1986). Long, Baer, Colquitt, Outlaw, and Dhensa-Kahlon (2015) found that employees can enhance their image by forming supportive relationships not only with organizational “stars” (i.e., co-workers who are already top performers) but also with “projects” (i.e., co-workers who, with support, could potentially be top performers). Thus, making the “right” connections may sometimes depend on how those connections are viewed by observers.

Dimensions

Some theorists have proposed taxonomies that specify the basic dimensions of impression management (Jones & Pittman, 1982; Tedeschi & Melburg, 1984), and scales have been developed to measure them (Bolino & Turnley, 1999). The most influential of these taxonomies is perhaps Jones and Pittman’s (1982) distinction among self-presentations that involve ingratiation (likeability), self-promotion (competence), exemplification (morality, dedication), supplication (weakness), and intimidation (threateningness), although other dimensions have also been suggested. These taxonomies are often useful, but they obscure the fact that, depending on how thinly one slices the self-presentational pie, the number and variety of dimensions on which people may manage their impressions are virtually endless. People are usually quite selective in the precise dimensions that they invoke in a particular encounter. For example, employees rarely try to convey an image of omnibus competence but rather emphasize self-presentations that are relevant to circumscribed competencies that are valued in a particular context. Likewise, exemplification encompasses many specific images, such as impressions of being ethical, moral, dedicated, conscientious, loyal, and trustworthy, which are not interchangeable as self-presentational tactics. The broad dimensions discussed by Jones and Pittman (1982) and others are useful conceptually but are often not precise enough for either research purposes or application to organizational settings.

p.258

Furthermore, although research has tended to examine only one or two dimensions in a particular study, real-world impression management often involves simultaneous attention to a set of diverse dimensions – a self-presentational “persona” (Leary & Allen, 2011). For example, not only may an employee be motivated for co-workers to view him positively along several dimensions simultaneously (such as competent, pleasant, cooperative, conscientious, and ethical), but successfully conveying a desired image on one dimension may require self-presentational efforts on other dimensions as well. For example, emphasizing one’s competence or conscientiousness may undermine impressions of pleasantness unless the employee takes steps not to seem braggartly or compulsive (Berman, Levine, Barasch, & Small, 2014). Only a few studies have examined self-presentations on multiple dimensions simultaneously (e.g., Bolino & Turnley, 2003a; Leary, Robertson, Barnes, & Miller, 1986), and more work along these lines is needed.

Actors’ and Perceivers’ Perspectives on Impression Management

Work within both social psychology and organizational behavior has examined impression management almost exclusively from the standpoint of the actor who is attempting to convey particular impressions of him- or herself. Most theory has dealt exclusively with factors that operate at the level of the actor – such as goals, self-perceptions, and judgments of one’s self-presentational efficacy – and most research has studied either situational factors that affect the actor’s self-presentational efforts or dispositional variables that moderate the effects of those external influences.

In part, this focus on the actor can be traced to Goffman’s (1959) dramaturgical approach, which conceptualized self-presentation as a process by which actors play a role before an audience (see, also, Schlenker, 1980). The dramaturgical metaphor is fine as far as it goes, but in most theatrical performances, actors usually play their parts irrespective of how the audience reacts. Yet, when people manage their impressions in everyday life, they are usually engaged in an interdependent interaction in which actors and perceivers mutually influence one another. Thus, each actor is sensitive to perceivers’ reactions and often modifies his or her behaviors on the fly in response to feedback from the perceiver (Bozeman & Kacmar, 1997). To complicate matters, each actor in an encounter is simultaneously a perceiver of the self-presentations of other actors. In organizational settings, each employee tries to control others’ impressions of him or her at the same time that other employees are doing the same thing.

p.259

FIGURE 11.1 An Actor–Perceiver Model of Impression Management in Organizations

As a result, a person’s perceptions as an observer may influence his or her own self-presentations, and one’s self-presentations may influence both others’ impressions of the actor and their self-presentations to him or her (Baumeister, Hutton, & Tice, 1989; Vorauer & Miller, 1997). Accordingly, to understand how impression management plays out in organizational settings, one must consider not only the determinants of actors’ self-presentational efforts (the standard approach) but also the inferences and interpretations that perceivers draw and the effects of those perceptions on perceivers’ own self-presentations when in the role of actor.

In the sections that follow, we sketch a picture of impression management that considers actors’ self-presentations, perceivers’ impressions of the actor, and actors’ responses to perceivers’ responses. Of course, dynamic models of reciprocal influences are difficult to discuss and model, but we will lay out some basic ideas to guide future work. Figure 11.1 provides an overview of the process described below.

The Actor’s Perspective: Determinants of Impression Management

To provide an overview of factors that influence impression management, we rely on a two-component model that distinguishes between two fundamental processes that underlie impression management (Leary & Kowalski, 1990). One component involves processes that affect the degree to which people are motivated to control how others see them (impression motivation), and the other involves processes that determine the specific impressions that people try to convey in a given context (impression construction).

p.260

Impression Motivation

Sometimes, people’s impressions are irrelevant to their immediate or long-term goals. Assuming that one does not give the impression of being dangerous or insane, people can successfully execute many of the tasks of life – such as buying groceries or commuting to work – with little concern for their social images. However, in many instances, the likelihood of achieving one’s goals is affected, sometimes dramatically, by making the “right” impression (or at least not making the “wrong” impression), whatever that might be in a given context. The more relevant one’s impressions are to one’s goals, the more motivated a person will be to convey a desired impression – that is, an impression that increases the likelihood of achieving the desired goal. So, first and foremost, impression motivation is influenced by the degree to which one’s impressions are relevant to one’s goals. For instance, because impressions are centrally important to being hired for a job and, later, being promoted within that job, job applicants and employees are understandably motivated to convey impressions that increase their likelihood of getting the job or promotion and to avoid making impressions that undermine those goals (Barrick et al., 2009). Likewise, when employees feel insecure in their jobs, they are more likely to manage their image at work proactively (Huang, Zhao, Niu, Ashford, & Lee, 2013).

Of course, the more valuable or important the goal is, the higher impression motivation will be. Not surprisingly, organizational researchers have focused on understanding the use and effects of impression management on hiring decisions and performance appraisal ratings, which are important outcomes for employees at all organizational levels (Bolino et al., 2016). But organizational studies have also investigated impression management at the upper echelons of organizations, where the stakes are often particularly high. For example, Graffin, Carpenter, and Boivie (2011) found that boards of directors sometimes use “strategic noise” to deliberately obscure details of their selection of a new CEO in order to manage stakeholders’ impressions, particularly when the new CEO does not have prior experience as a chief executive or comes from a firm that is less well-regarded. Likewise, Chen, Luo, Tang, and Tong (2014) found that interim CEOs use impression management with regard to firm earnings in order to be promoted to the position permanently. Furthermore, CEOs, board members, and other top managers often use impression management and ingratiation to enhance or maintain their credentials and status (e.g., Maitlis, 2005; Westphal, 1998; Westphal & Stern, 2006). Put simply, when critical outcomes are at stake, the motivation to manage impression is greater.

Third, impression motivation is particularly high when people perceive a discrepancy between their current image and the image they desire to make. For instance, Bolino (1999) argued that employees sometimes engage in OCB to make up for a transgression or poor performance that has undermined their reputation at work. By doing so, employees who are concerned that they are viewed as weak contributors seek to be regarded as good organizational citizens. Conversely, employees who are seen as competent may pretend to know less than they really do in order to avoid being inundated with requests for assistance from their peers (Becker & Martin, 1995). As such, impression management is sometimes motivated by the desire to reshape one’s image, which, as described later, can be difficult.

p.261

Impression Construction

Leary and Kowalski (1990) hypothesized that the specific images that people try to construct are influenced by five primary sets of factors: desired and undesired identity images, the target’s values, role constraints, the actor’s current social image, and the actor’s self-concept. Desired identity images are images that an actor believes will increase the probability of achieving desired goals, and undesired images are those that the actor thinks will decrease the likelihood of achieving desired goals. In organizational settings, desired identity images involve attributes that promote one’s outcomes on the job. Although the specific images that employees regard as desired differ greatly by organizational context (the desired images for a kindergarten teacher are quite different than those for a prison guard, for example), they tend to fall into three primary clusters of images that convey (1) job-relevant knowledge and competence, (2) interpersonal attributes such as collegiality, cooperativeness, and organizational loyalty, and (3) personal qualities such as self-discipline, conscientiousness, and honesty.

However, actors must also consider the idiosyncratic values and desires of particular targets. For instance, Gardner and Avolio (1998) suggested that charismatic leaders must find ways to manage impressions that facilitate the alignment of leaders’ and followers’ motives. Similarly, in the context of job interviews, successful applicants must present themselves in ways that convince interviewers that the applicants have the right knowledge, skills, and abilities for the job and that they are a good fit for the organization (Higgins & Judge, 2004; Kristof-Brown, Barrick, & Franke, 2002). Therefore, in order to manage impressions successfully, having an understanding of the perceiver’s values and beliefs is important.

Furthermore, the images that people can reasonably project are often constrained by who they are and the roles that they play in an organization. For instance, new employees are limited in how they can present themselves because organizational newcomers are frequently encouraged to adopt identities that are consistent with the organization’s values (Cable, Gino, & Staats, 2013); even experienced employees often feel compelled to act like they share the organization’s values even when they do not (Hewlin, 2003). Likewise, subordinates are often concerned that making critical, but constructive, suggestions might undermine their image as a team player and harm their career prospects (Detert & Edmondson, 2011). Certain work arrangements may also affect the use and effectiveness of impression management in organizations. For example, employees who work remotely may feel greater pressure to manage impressions with their supervisors owing to their diminished visibility at the office, affecting the types of tactics that employees use and how often they use them (Barsness, Diekmann, & Seidel, 2005). Finally, studies show that women in organizational contexts must be careful about projecting a masculine image because counter-normative impressions often elicit a “backlash” effect (e.g., Bolino & Turnley, 2003b; Rudman, 1998).

p.262

Even when situational factors prescribe and proscribe certain images, people are unlikely to try to convey impressions that they don’t think they can maintain. Thus, actors’ self-concepts come into play as they judge whether conveying a particular image is deceptive and whether they have the ability to maintain the desired image. Indeed, even employees who successfully engage in interview faking behavior (Levashina & Campion, 2007) to land a job are soon likely to find themselves in a difficult position if they conveyed that they possess knowledge, skills, or abilities that they do not really possess. For this reason, people generally avoid trying to be seen in ways that are highly divergent from how they see themselves.

The Perceiver’s Perspective: Drawing Inferences From Public Images

Only a portion of a person’s behavior conveys useful information to other people. Indeed, perceivers often do not know whether a particular behavior says anything noteworthy whatsoever about the actor. A particular behavior may reflect a variety of influences – traits, motives, goals, habits, momentary states, and social pressures – only some of which may be of interest to a perceiver.

Much of the research in the area of social cognition has dealt with factors that influence how perceivers decide, correctly or not, whether to draw “correspondent inference” about a person on the basis of his or her actions. (These are called correspondent inferences because the perceiver infers that the actor possesses a characteristic that corresponds to the observed behavior; Jones & Davis, 1965; Jones & McGillis, 1976.) Although people draw some such conclusions in a logical fashion (Kelley, 1967), research has also demonstrated several biases in how people jump from observed behaviors to inferences about the person. For example, observers are biased to infer that behaviors reflect an actor’s inner dispositions rather than the effects of situational influences (Gilbert & Malone, 1995), particularly when the behavior is undesirable.

Most theory and research on person perception and attribution does not consider the important role that self-presentation plays in these processes. In many settings – including work organizations – observers are aware that actors are motivated to convey particular impressions of themselves that will promote their personal goals within the organization. Thus, observers often have reason to be skeptical that the behavior does not accurately reflect the actor’s actual goals, ability, or other characteristics.

p.263

A good deal of organizational research has examined the degree to which various tactics shape other people’s impressions of the actor (Bolino et al., 2016), but we know relatively little about how perceivers decide whether actors’ behaviors are genuine reflections of their personal characteristics or tactical self-presentations intended to convey the impression of having those characteristics. Nor do we know a great deal about how perceivers respond when they conclude that a particular behavior is a deceptive self-presentation rather than a reflection of an actual characteristic. Even so, we speculate below on how awareness of self-presentation might influence perceivers’ impressions of an actor.

Vigilance

Just as actors are more strongly motivated to impression-manage in certain contexts or with certain targets than with others, perceivers may be more or less vigilant to the possibility that an actor’s surface impressions do not reflect reality. Vigilance does not imply that the perceiver necessarily distrusts the impressions – only that factors have made him or her attentive to the possibility that a behavior reflects tactical self-presentation rather than an actor’s actual characteristics. Two factors stand out – the perceived importance of the characteristic to the actor’s outcomes, and the perceived costs of inferential error.

In every job (or job interview), certain characteristics and credentials are more important than others, and perceivers are more likely to be vigilant to the veracity of impressions that are relevant to important characteristics than to information regarding less important traits. As a result, actors should be able to manage their impressions on less important dimensions more successfully than on more important ones. Vigilance also increases to the degree that perceivers recognize that the actor has much at stake and, thus, is motivated to convey the desired impression. For example, job interviewers, admissions committees, parole boards, and even targets of sexual advances may doubt the truthfulness of proffered images.

Increased vigilance when the stakes are high is the basis of the “ingratiator’s dilemma”: situations in which actors are highly motivated to manage their impressions are also those in which perceivers are most likely to be suspicious of their motives and the veracity of the images (Jones, 1990). For the same reason, perceivers who are of high status or in positions of power vis-à-vis the actor may regard actors’ impressions with suspicion. Fortunately for actors, perceivers are more inclined to take their self-presentations at face value than they probably should (Vonk, 2002), and a recent study found that interviewers have an especially hard time detecting the use of deceptive impression management (Roulin et al., 2015).

p.264

Related to importance is the perceived cost of drawing incorrect conclusions about the actor’s characteristics. When the costs of an inferential error are high, perceivers will be more vigilant to the possibility of self-presentational duplicity. For example, when an interviewer has two highly qualified applicants for a job, the costs of turning down one applicant in favor of the other is higher than when there is only one good applicant to hire. In these situations, the interviewer may give greater consideration to the possibility that the applicants could be managing their impressions. Conversely, interviewers may be less vigilant when there is only one qualified applicant or one applicant is clearly better than the other because the costs of missing out on a qualified applicant are low.

Although the role of dispositional trust among perceivers has not been examined, people who are more trusting (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995) may be more inclined to take people’s self-presentations at face value. In contrast, individuals with Machiavellian tendencies may be more skeptical of the images that people present (Dahling, Whitaker, & Levy, 2009). Thus, some people may tend to be more or less vigilant in scrutinizing the images that others present.

Prior Knowledge

People’s perceptions of others are strongly influenced by their expectations and preconceptions (Snyder, 1981; Synder & Cantor, 1979). As a result, perceivers’ impressions of an actor in a given setting are affected by what they believe to be true, whether through personal experience or reputation. Thus, the effect of a particular self-presentational action may have different effects depending on the perceiver’s existing image of the actor. Similarly, impression management may be more effective in the early stages of a relationship (Cooper, 2005).

Self-presentations that are congruent with perceivers’ existing views of the actor may not affect the perceivers’ impressions of the actor at all (if they are even noticed) because self-presentational inferences that are close to perceivers’ existing impressions may be assimilated. One exception may be cases in which the perceiver’s views of the actor are newly formed or tentative, in which case a congruent self-presentational inference may strengthen the existing impression.

When perceivers draw an inference that is contrary to their existing impression of the actor, they face attributional ambiguity with respect to the cause of the discrepancy. Perhaps their existing impression of the actor was inaccurate, their impression of the actor was incomplete (in the sense of not including contextually based variations in behavior), the behavior was an aberration due to unusual extenuating circumstances or strong external pressures, or, most relevant to this discussion, the behavior was a self-presentational ploy intended to convey an impression that was not accurate.

The latter possibility is an interesting and overlooked consideration in the literatures on social perception and impression management. Beyond the fact that perceivers conclude that they cannot draw correspondent inferences from the action, perceivers may view even desirable behaviors, such as actions that convey exemplary organizational citizenship, less favorably when they are perceived to arise from self-presentational goals than from genuine desire to help co-workers or the organization (Grant, Parker, & Collins, 2009; Huang et al., 2013). Likewise, efforts to be seen as likeable may backfire at times, particularly when people lack political or social skill (Harris, Kacmar, Zivnuska, & Shaw, 2007; Higgins, Judge, & Ferris, 2003; Turnley & Bolino, 2001). Indeed, even perceiving that an actor is intentionally trying to convey an accurate impression (such as managing impression to convey one’s true abilities or genuine emotions) may generate undesired secondary impressions of insecurity, trying too hard, or “brown-nosing.” Thus, perceivers may respond negatively even when the presented image is veridical.

p.265

The Actor Reacts

People who desire to make a particular impression on a perceiver will, of course, attempt to determine whether their efforts have been successful (Bozeman & Kacmar, 1997). Occasionally, they receive explicit information about how others view them, but they usually must infer how they are being perceived on the basis of vague and indirect information. Information about others’ views may be more limited in organizational settings than in ordinary interpersonal life. People’s interactions in organizations are often role-bound and task-oriented, and norms discourage expressions of feedback except when one person is in a formal position to evaluate another, and even then, supervisors are often reluctant to give negative feedback (Larson, 1989). Our friends, family members, and intimate partners have a bit more license to tell us what they think of us than our co-workers do.

Only a few studies have examined the degree to which people can infer other people’s impressions of them, and these studies have typically examined passive impressions rather than judgments of the success of active efforts to impression-manage. Studies show that people have a general sense of the kinds of impressions that people in general have of them, although the relationships are not strong (Kenny & DePaulo, 1993). Fine-grained accuracy may not be necessary for successful interactions and interpersonal effectiveness. In many instances, it may be sufficient to know whether other people perceive one as being above or below some criterion on a characteristic; knowing precisely how low or high may matter less. So, an employee may perceive that co-workers perceive him as conscientious or cooperative, without necessarily knowing where, on a 7-point scale, their ratings might fall.

Although people have a general sense of how they are viewed in general and seem to know how they are perceived on core personality traits, they are less good at judging how particular people see them, and they are particularly bad at assessing how positively or negatively others evaluate them (Carlson & Kenny, 2012). Furthermore, people show a clear bias to believe that others perceive them more positively than is the case, probably due to others’ tendency to hide or mask negative reactions.

p.266

Given the dearth of explicit feedback regarding how one is coming across, people must rely mostly on their own judgments of self-presentational success. As in many cases of self-perception, people’s assessments of their public images are likely biased by knowledge of their own motives and intentions. Knowing that one wishes the boss to view them as a dedicated employee and knowing the things one has done to be seen as dedicated, an employee may overestimate the degree to which he or she was successful. Research has documented an “illusion of transparency” in which people overestimate the degree to which others can read their emotional states (Gilovich, Savitsky, & Medvec, 1998), and this likely applies to reading their personal characteristics as well.

Work in both social psychology and organizational behavior has explored individual differences in self-presentational effectiveness. By far, the most widely studied construct in this vein has been self-monitoring, the degree to which people are attentive to their public image and work toward controlling their self-presentations to others (see Snyder & Fuglestad, 2009). Overall, self-monitoring predicts self-presentational behaviors and effectiveness in both laboratory experiments and organizational settings (Fandt & Ferris, 1990; Kilduff & Day, 1994; Turnley & Bolino, 2001; see Fuglestad & Snyder, 2009).

Although people have difficulty inferring others’ impressions of them, doing so is easier when they have clearly suffered a loss of face. People typically know when their public failures, inept execution of job duties, and personal embarrassments have damaged their public images even when no one else acknowledges them. People are highly sensitive to their lapses and tend to assume that their self-presentation predicaments are more observable and widely known than they are (e.g., the spotlight effect; Gilovich, Medvec, & Savitsky, 2000). This bias to overestimate the severity of one’s self-presentational failures may be functional, in that it is arguably better to overestimate the seriousness of a self-presentational problem than to underestimate or overlook it.

Future Directions and Conclusion

We have suggested ideas for research throughout the chapter but wish to conclude by offering a few additional topics that might provide particularly large dividends. First, we know almost nothing about the circumstances under which people opt to use self-presentation to advertise their actual attributes as opposed to convey false images of themselves. This topic is particularly important in organizational settings, in which successfully conveying inaccurate images for personal gain may result in negative organizational outcomes such as bad hiring decisions, employee incompetence, and poor management. Organizations and managers need to have accurate views of their employees, and impression management can work against that goal. To complicate matters, employees simultaneously manage multiple impressions to various audiences (supervisors, subordinates, colleagues, clients, etc.), making the task of knowing what employees are “really” like difficult. Understanding how people make and implement these self-presentational choices and how these choices change as a function of role and stage of career would advance both social and organizational psychology.

p.267

As noted, we also know almost nothing about how people assess how others view them, but the implications of inaccurate judgments for personal, interpersonal, and organizational outcomes can be notable. Understanding the processes by which people assess both their current images and the effectiveness of their self-presentational efforts are exceptionally important topics. We suspect that, in many organizations, self-presentational accuracy predicts not only job performance but also social climate and employee morale and that the importance of understanding how one is viewed by others typically increases as one moves up an organizational hierarchy.

As we have seen, research in social psychology and organizational behavior converge to illuminate the complex interplay of actors and observers as people manage their impressions in pursuit of their personal and interpersonal goals. Although impression management is an important feature of most interpersonal encounters, it may play a particularly pivotal role in organizational settings in which images of competence, trustworthiness, status, and collegiality are integral not only to individuals’ personal goals, as they are in all interpersonal encounters, but also to the performance of groups, teams, departments, and entire organizations.

Note

1 Although the terms impression management and self-presentation are often used interchangeably, technically they are slightly different. Whereas a person may manage other people’s impressions of a variety of entities – not only oneself but also other people (friends, family members, political candidates, etc.), organizations, businesses, cities, and so on – self-presentation refers specifically to managing others’ impressions of oneself. Thus, impression management refers to a broader category of behaviors of which self-presentation is a subset. When dealing with controlling impressions of oneself, both terms are equally appropriate, and we use both in this chapter.

References

Barrick, M. R., Shaffer, J. A., & DeGrassi, S. W. (2009). What you see may not be what you get: Relationships among self-presentation tactics and ratings of interview and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1394–1411.

Barsness, Z. I., Diekmann, K. A., & Seidel, M. D. L. (2005). Motivation and opportunity: The role of remote work, demographic dissimilarity, and social network centrality in impression management. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 401–419.

p.268

Baumeister, R. F. (1982). A self-presentational view of social phenomena. Psychological Bulletin, 91, 3–26.

Baumeister, R. F., Hutton, D. G., & Tice, D. M. (1989). Cognitive processes during deliberate self-presentation: How self-presenters alter and misinterpret the behavior of their interaction partners. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 59–78.

Becker, T. E., & Martin, S. L. (1995). Trying to look bad at work: Methods and motives for managing poor impressions in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 174–199.

Berman, J. Z., Levine, E. E., Barasch, A., & Small, D. A. (2014). The braggart’s dilemma: On the social rewards and penalties of advertising prosocial behavior. Journal of Market Research, 51, 90–104.

Bolino, M. C. (1999). Citizenship and impression management: Good soldiers or good actors? Academy of Management Review, 24, 82–98.

Bolino, M. C., Kacmar, K. M., Turnley, W. H., & Gilstrap, J. B. (2008). A multi-level review of impression management motives and behaviors. Journal of Management, 34, 1080–1109.

Bolino, M. C., Long, D., & Turnley, W. (2016). Impression management in organizations: Critical questions, answers, and areas for future research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3, 377–406.

Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (1999). Measuring impression management in organizations: A scale development based on the Jones and Pittman taxonomy. Organizational Research Methods, 24, 237–250.

Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (2003a). More than one way to make an impression: Exploring profiles of impression management. Journal of Management, 29, 141–160.

Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (2003b). Counternormative impression management, likeability, and performance ratings: The use of intimidation in an organizational setting. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 237–250.

Bozeman, D. P., & Kacmar, K. M. (1997). A cybernetic model of impression management processes in organizations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 69, 9–30.

Cable, D. M., Gino, F., & Staats, B. R. (2013). Breaking them in or eliciting their best? Reframing socialization around newcomers’ authentic self-expression. Administrative Science Quarterly, 58, 1–36.

Carlson, E., & Kenny, D. A. (2012). Meta-accuracy: Do we know how others see us? In S. Vazire (Ed.), Handbook of self-knowledge (pp. 242–257). New York: Guilford Press.

Chen, G., Luo, S., Tang, Y., & Tong, J.Y. (2014). Passing probation: Earnings management by interim CEOs and its effect on their promotion prospects. Academy of Management Journal, 58, 1389–1418.

Cialdini, R. B., Borden, R. J., Thorne, A.,Walker, M. R., Freeman, S., & Sloan, L. R. (1976). Basking in reflected glory: Three (football) field studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 360–375.

Cooper, C. D. (2005). Just joking around? Employee humor expression as an ingratiatory behavior. Academy of Management Review, 30, 765–776.

Dahling, J. J., Whitaker, B. G., & Levy, P. E. (2009). The development and validation of a new Machiavellianism scale. Journal of Management, 35, 219–257.

Detert, J. R., & Edmondson, A. C. (2011). Implicit voice theories: Taken-for-granted rules of self-censorship at work. Academy of Management Journal, 54, 461–488.

p.269

Ellemers, N., & Barreto, M. (2006). Social identity and self-presentation at work: how attempts to hide a stigmatised identity affect emotional well-being, social inclusion and performance. Netherlands Journal of Psychology, 62, 51–57.

Elsbach, K. D. (2004). Interpreting workplace identities: The role of office décor. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 99–128.

Fandt, P. M., & Ferris, G. R. (1990). The management of information and impressions: When employees behave opportunistically. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 45, 140–158.

Ferris, G. R, Judge, T. A., Rowland, K. M., & Fitzgibbons, D. E. (1994). Subordinate influence and the performance evaluation process: Test of a model. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 58, 101–135.

Fuglestad, P. T., & Snyder, M. (2009). Self-monitoring. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 574–591). New York: Guilford Press.

Gardner, W. L., & Avolio, B. J. (1998). The charismatic relationship: A dramaturgical perspective. Academy of Management Review, 23, 32–58.

Gardner, W. L., & Martinko, M. J. (1988). Impression management in organizations. Journal of Management, 14, 321–338.

Giacalone, R. A., & Rosenfeld, P. (Eds.) (1990). Impression management in the organization. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Giacalone, R. A., & Rosenfeld, P. (Eds.) (1991). Applied impression management: How image-making affects managerial decisions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Gilbert, D. T., & Malone, P. S. (1995). The correspondence bias. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 21–38.

Gilovich, T., Medvec, V. H., & Savitsky, K. (2000). The spotlight effect in social judgment: An egocentric bias in estimates of the salience of one’s own actions and appearance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 211–222.

Gilovich, T., Savitsky, K., & Medvec, V. H. (1998). The illusion of transparency: Biased assessments of others’ ability to read one’s emotional states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 332–346.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Doubleday.

Gosling, S. D., Ko, S. J., Mannarelli, T., & Morris, M. E. (2002). A room with a cue: Personality judgments based on offices and bedrooms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(3), 379–398.

Graffin, S., Carpenter, M., & Boivie, S. (2011). What’s all that (strategic) noise? Anticipatory impression management in CEO successions. Strategic Management Journal, 32, 748–770.

Grant, A. M. (2016, June 4). Unless you’re Oprah, “be yourself” is terrible advice. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/05/opinion/sunday/unless-youre-oprah-be-yourself-is-terrible-advice.html

Grant, A. M., Parker, S. K., & Collins, C. G. (2009). Getting credit for proactive behavior: Supervisor reactions depend on what you value and how you feel. Personnel Psychology, 62, 31–55.

Harris, K. J., Kacmar, K. M., Zivnuska, S., & Shaw, J. D. (2007). The impact of political skill on impression management effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 278–285.

Hewlin, P. F. (2003). And the award for best actor goes to. . .: Facades of conformity in organizational settings. Academy of Management Review, 28, 633–642.

p.270

Higgins, C. A., & Judge, T. A. (2004). The effect of applicant influence tactics on recruiter perceptions of fit and hiring recommendations: A field study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 622–632.

Higgins, C. A., Judge, T. A., & Ferris, G. R. (2003). Influence tactics and work outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 89–106.

Huang, G. H., Zhao, H. H., Niu, X. Y., Ashford, S. J., & Lee, C. (2013). Reducing job insecurity and increasing performance ratings: Does impression management matter? Journal of Applied Psychology, 98, 852–862.

Jones, E. E. (1990). Interpersonal perception. New York: Freeman.

Jones, E. E., & Davis, K. E. (1965). From acts to dispositions: the attribution process in person perception. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 219–266). New York: Academic Press.

Jones, E., & McGillis, D. (1976). Correspondent inferences and the attribution cube: A comparative reappraisal. In J. Harvey, W. Ickes, & R. Kidd (Eds.), New directions in attribution research (pp. 192–238). New York: Erlbaum.

Jones, E. E., & Pittman, T. S. (1982). Toward a general theory of strategic self-presentation. In J. Suls (Ed.), Psychological perspectives on the self (Vol. 1, pp. 231–262). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Judge, T. A., & Bretz, R. D. (1994). Political influence behavior and career success. Journal of Management, 20, 43–65.

Kelley, H. H. (1967). Attribution theory in social psychology. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 15, 192–238.

Kenny, D. A., & DePaulo, B. M. (1993). Do people know how others view them? An empirical and theoretical account. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 145–161.

Kilduff, M., & Day, D. V. (1994). Do chameleons get ahead? The effects of self-monitoring on managerial careers. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 1047–1060.

Kowalski, R. M., & Leary, M. R. (1990). Strategic self-presentation and the avoidance of aversive events: Antecedents and consequences of self-enhancement and self-depreciation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 26, 322–336.

Kristof-Brown, A., Barrick, M.R., & Franke, M. (2002). Applicant impression management: Dispositional influences and consequences for recruiter perceptions of fit and similarity. Journal of Management, 28, 27–46.

Larson, J. R. (1989). The dynamic interplay between employees’ feedback-seeking strategies and supervisors’ delivery of performance feedback. Academy of Management Review, 14, 408–422.

Latham, G. P., Almost, J., Mann, S., & Moore, C. (2005). New developments in performance management. Organizational Dynamics, 34, 77–87.

Leary, M. R. (1995). Self-presentation: Impression management and interpersonal behavior. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Leary, M. R., & Allen, A. B. (2011). Self-presentational persona: Simultaneous management of multiple impressions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 1033–1049.

Leary, M. R., Allen, A. B., & Terry, M. L. (2011). Managing social images in naturalistic versus laboratory settings: Implications for understanding and studying self-presentation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 411–421.

Leary, M. R., & Kowalski, R. M. (1990). Impression management: A literature review and two-component model. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 34–47.

Leary, M. R., Robertson, R. B., Barnes, B. D., & Miller, R. S. (1986). Self-presentations of small group leaders as a function of role requirements and leadership orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 742–748.

p.271

Levashina, J., & Campion, M. A. (2007). Measuring faking in the employment interview: Development and validation of an interview faking behavior scale. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1638–1656.

Long, D. M., Baer, M. D., Colquitt, J. A., Outlaw, R., & Dhensa-Kahlon, R. K. (2015). What will the boss think? The impression management implications of supportive relationships with star and project peers. Personnel Psychology, 68, 463–498.

Maitlis, S. (2005). Taking it from the top: How CEOs influence (and fail to influence) their boards. Organization Studies, 25, 1275–1311.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709–734.

Morrison, E. W., & Bies, R. J. (1991). Impression management in the feedback-seeking process: A literature review and research agenda. Academy of Management Review, 16, 522–541.

Murphy, N. A. (2007). Appearing smart: The impression management of intelligence, person perception accuracy, and behavior in social interaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 325–339.

Parhankangas, A., & Ehrlich, M. (2014). How entrepreneurs seduce business angels: An impression management approach. Journal of Business Venturing, 29, 543–564.

Peluchette, J., & Karl, K. (2009). Examining students’ intended image on Facebook: “What were they thinking?!” Journal of Education for Business, 85, 30–37.

Rosenfeld, P., Giacalone, R. A., & Riordan, C. A. (1995). Impression management in organizations. London: Routledge.

Roulin, N., Bangerter, A., & Levashina, J. (2015). Honest and deceptive impression management in the employment interview: Can it be detected and how does it impact evaluations? Personnel Psychology, 68, 395–444.

Rudman, L. A. (1998). Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 629–645.

Schlenker, B. R. (1980). Impression management: The self-concept, social identity, and interpersonal relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Schlenker, B. R. (2012). Self-presentation. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 542–570). New York: Guilford Press.

Snyder, C. R., Lassegard, M., & Ford, C. E. (1986). Distancing after group success and failure: Basking in reflected glory and cutting off reflected failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(2), 382–388.

Snyder, M. (1981). Seek, and ye shall find: Testing hypotheses about other people. In Social Cognition: The Ontario Symposium (Vol. 1, pp. 277–303). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Snyder, M., & Cantor, N. (1979). Testing hypotheses about other people: The use of historical knowledge. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 15, 330–342.

Snyder, M. & Fuglestad, P. T. (2009). Self-monitoring. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Individual differences in social behavior (pp. 574–591). New York: Guilford Press.

Tedeschi, J. T., & Melburg, V. 1984. Impression management and influence in the organization. In S. B. Bacharach & E. J. Lawler (Eds.), Research in the sociology of organizations (Vol. 3, pp. 31–58). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Turnley, W. H., & Bolino, M. (2001). Achieving desired images while avoiding undesired images: Exploring the role of self-monitoring in impression management. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 351–360.

p.272

Van Der Heide, B., D’Angelo, J. D., & Schumaker, E. M. (2012). The effects of verbal versus photographic self-presentation on impression formation in Facebook. Journal of Communication, 62, 98–116.

Vonk, R. (2002). Self-serving interpretations of flattery: Why ingratiation works. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 515–526.

Vorauer, J. D., & Miller, D. T. (1997). Failure to recognize the effect of implicit social influence on the presentation of self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 281–295.

Wayne, S. J., & Ferris, G. R. 1990. Influence tactics, affect, and exchange quality in supervisor-subordinate interactions: A laboratory experiment and field study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 487–499.

Wayne, S. J., & Liden, R. C. 1995. Effects of impression management on performance ratings: A longitudinal study. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 232–260.

Westphal, J. D. (1998). Board games: How CEOs adapt to increases in structural board independence from management. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43, 511–537.

Westphal, J. D., & Deephouse, D. L. (2011). Avoiding bad press: Interpersonal influence in relations between CEOs and journalists and the consequences for press reporting about firms and their leadership. Organization Science, 22, 1061–1086.

Westphal, J. D., & Stern, I. (2006). The other pathway to the boardroom: How interpersonal influence behavior can substitute for elite credentials and demographic majority status in gaining access to board appointments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51, 169–204.