Introduction

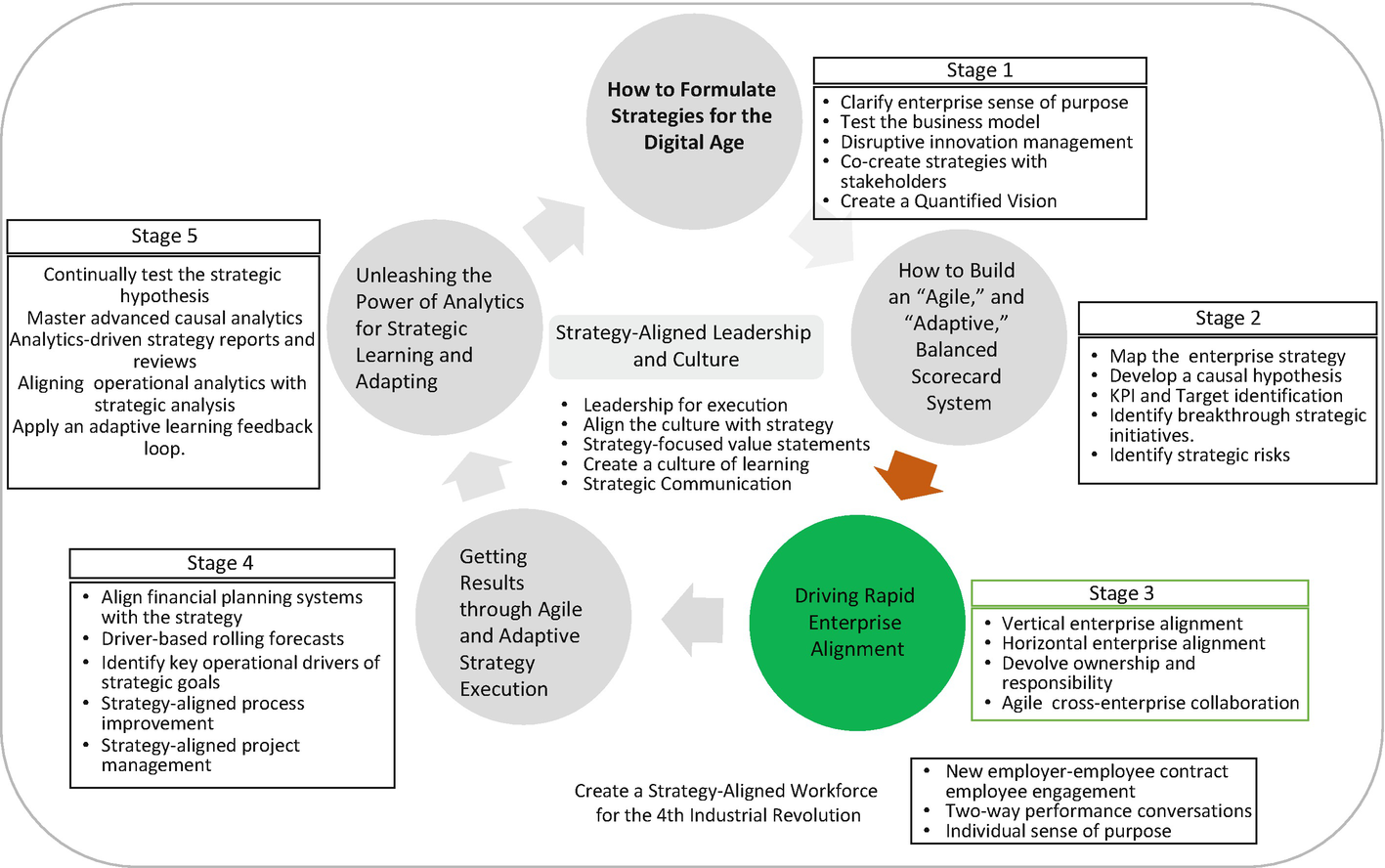

Stage 3. Driving rapid enterprise alignment

However, to align all of the organization to the strategy, then, we need an agile process and mechanism to align devolved objectives, Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), and initiatives/actions toward the strategy of the enterprise.

Traditional Approaches

Hoshin Kanri

Traditionally, many organizations have done this through approaches such as Hoshin Kanri, a seven-step process that involves the translation of a strategic vision plan into a set of clear objectives that are then realized through the execution of precisely defined tactical actions and projects.

Run to an annual cycle, Hoshin Kanri emerged in the 1960s in Japan out of the total quality movement and is based very much on the Shewhart/Deming plan-do-check act cycle.

Catchball

Hoshin uses a process called “catchball” to align all efforts across the organization. First, the catchball process translates strategies into increasingly lower-level objectives in a “cause-and-effect” way. Catchball then ensures that all the objectives at every level are well coordinated across process and functional lines.

A Strategy Map (in particular, at the theme level) can be used to guide the annual Hoshin Kanri process.

Thai Carbon Black Case Illustration

Palladium Hall of Fame inductee Thai Carbon Black—TCB—the largest single-plant producer of carbon black, the fine powder used in rubber manufacturing, chiefly for automobile tires, used both the Balanced Scorecard and Hoshin Kanri in a cascading strategy.

TCB’s Quality Council (a senior executive team) decided to adopt the Balanced Scorecard, making it the central tool in its management arsenal. The Balanced Scorecard helped define and map strategy. Together with Hoshin-Kanri and Total Quality Management, it would help set goals and execute strategy. (Later, Six Sigma was used tactically within strategic initiatives).

The executive team sets a five-year strategic plan that it assesses and refines each year—along with the Strategy Map—in the Management Review and Quality Council meetings. The result is a one-year plan, known as the Presidents Policy, which contains key performance targets that align to each of the four Balanced Scorecard perspectives. Using catchball, TCB sets targets and supporting measures.

Senior managers set high-level strategic measures, targets, and “managing points” (key objectives, which must be approved by the president).

Through a dialogue with their direct reports, managers identify supporting measures for the level below, down to the supervisor level. “Checking points,” components of the managing points, are in turn the responsibility of subordinate managers. At each level, action plans are launched to drive performance.

Balanced Scorecard

The corporate system serves as the steer for the divisional, strategic business unit and functional scorecards—or variations thereof. For more conventional Balanced Scorecard users, cascading (which, as we explain below, is not synonymous with alignment) is typically delivered through building Balanced Scorecard systems at a devolved level—a devolved approach.

Conventional Scorecard Shortcomings

Although widely used, and seemingly sensible for making “strategy everyone’s everyday job,” over the last couple of decades, practice has uncovered some potential shortcomings of the conventional scorecard cascading approach.

First, it is common for the cascade process to take an inordinate and enervating amount of time, especially when a large suite of scorecard systems is being built. By the time the final piece of the enterprise-wide scorecard jigsaw is in place, the picture the puzzle shows no longer accurately describes the strategy, or more usually, the required approach for its delivery. However, given the amount of time it takes to build, (sometimes up to a year—and even longer on occasions) there is little appetite to start again.

Secondly, the conventional cascade has always come with a suspicion of conforming to classical Tayloresque thinking. This well-crafted plan by leaders (as described in the top-level Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard) is handed over “as is” (or close to) for departmental managers to implement.

The classic scorecard approach is to cascade themes, objectives, and KPIs according to three dimensions—identical, contributory, and unique.

Identical

Relevant elements are identical to those on the enterprise strategy map and scorecard.

Contributory

Some elements are translated to articulate the unique and direct contributions of the specific unit.

New

Unit develops new elements that describe indirect contributions to the enterprise scorecard.

To be fair, Kaplan and Norton recommend (and as taught in the Palladium Balanced Scorecard certification boot camp—which the authors of this book have delivered on numerous occasions) that cascaded identical elements (from themes to initiatives) should only reflect shared priorities—and that this is most often seen in the financial and learning and growth perspectives. Too often, this is not the case, and everything from the top level is cascaded. “Here’s your objectives, KPIs, etc., – get on with it” (in keeping with the beloved Tayloresque diktat that managers think and reports do). After a while, the scorecard architects scratch their heads wondering why no one is taking this scorecard stuff seriously!

Too Cascade or Not

Before starting a cascade process, a useful question to ask is “do we need to cascade?” It is not always required, and usually not early in the scorecard journey. What precisely will cascading achieve? The stock answer of “aligning the organization to the strategy” is not enough, at least at the outset. Be clear about the tangible outcomes, in terms of results, working practices, structure, behaviours, and so on.

Also, consider whether the capabilities are in place to manage a suite of scorecard systems and how quickly the organization could change elements of the system if required.

There might also be times when a cascade is simply not required, which might be for specific organizational reasons, such as described in the Saatchi & Saatchi case study in Panel 1, where commonality and standardization across the globe (and in a very short timeframe) was a key reason for scorecard adoption.

Moreover, even if a cascade is required, it might be appropriate to pilot in a unit or function first, communicating progress and impact to the rest of the organization. During the pilot, the strategy team will also become more knowledgeable on what works, doesn’t work, and likely resistance triggers. This might save a lot of pain later.

An Agile Approach

Case Illustration: Statoil

The Norway-headquartered oil and gas giant Statoil is a long-term user of the Balanced Scorecard system (with the first scorecard build in 1997). With about 700 scorecards in use worldwide by about 20,000 employees—from corporate to team level—the organization takes a very different approach to the classic cascade .

As a mature Balanced Scorecard user, Statoil (which calls it’s system Ambition to Action) reached the conclusion that the conventional approach to cascading scorecards is not appropriate, at least not for them—a values-driven company. “When it comes to content, we prefer the word translation to cascading,” explains Bjarte Bogsnes, Senior Advisor, Performance Framework. “Cascading is about corporate instructing that these are your objectives, KPIs, etc.”

“However, in our culture we would very easily lose people’s commitment, ownership and motivation if we controlled them in this way. Empowering teams to develop their own Ambition to Actions transmits a message that we trust them and believe in their abilities.”

However, he does add that if such a translation should go wrong, then the team above should intervene, but this has never proven to be a real issue. “This is not a problem largely as a result of commitment to transparency – all Ambition to Actions are available for all to see online so inappropriate ideas are noted and not only by your manager. Transparency is a control mechanism for translation.”

Bogsnes continues that used in the right way, the Balanced Scorecard is a great tool for supporting performance and helping teams to manage themselves. “Unfortunately, many scorecard implementations seem to be about reinforcing centralized command-and-control,” he says. “Alignment is not about target numbers adding up on the decimal; it is about creating clarity about which mountain to climb.”

Ambition to Action Explained

Translate strategic choices into more concrete objectives, KPIs, and actions

Secure flexibility and room to act and perform

Activate Statoil’s values and its people and leadership principles.

“Almost all our competitors have management systems that in some form aim to meet the first purpose, creating strategic goals,” says Bogsnes, “but this loses what is key for success: autonomy and agility, trust and transparency, ownership and commitment. If your own Ambition to Action becomes nothing but a landing ground for instructions from above, both ownership and quality tend to walk out the door.”

An Ambition to Action starts with an ambition statement, a higher purpose. “Call it a vision, call it a mission. We don’t care, as long as it ignites and inspires,” says Bogsnes.

The Statoil ambition is to be “Globally competitive – an exceptional place to perform and develop.” This statement is translated into different versions across the company. “One of our technology teams, for instance, chose, “Execution for today, solutions for the future. In our team, we ...challenge traditional management thinking,” explains Bogsnes.

“We try to connect and align all these through translation (each team translating relevant Ambition to Actions, typically the one above),” continues Bogsnes. “What should our Ambition to Action look like in order to support the Ambition to Action(s) above? What kind of objectives, KPIs and actions do we need? Can we use those above? Or do we need something sharper because we are one-step closer to the front line?”

“In short, we want Ambition to Action to be something that helps local teams to manage themselves and perform to their full potential, while we at the same time secure sufficient alignment.”

He stressed that there are situations where instructions and cascading from above is necessary, “but this should be the exception and not the rule, which makes it more acceptable when it happens.”

That said, there are occasional exceptions to this rule that might require more formal “instruction,” at least over the shorter term, as explained in the Saatchi & Saatchi case study (Panel 1).

Change of Perspective Order

Interestingly, and very unusually, Statoil has switched the order of the scorecard perspectives. Finance is at the base and people and organization (its spin on learning and growth) on top. Bogsnes describes the thinking here. “We all know what happens in business review meetings when the agenda is tight and time is limited,” he says. “Let’s come back to people and organization next time, which then doesn’t happen when next time comes. Those are not the signals to send if we claim to be a people-focused organization, so now People and Organization sits at the top. Another small gap closed between what we say and what we do.”

Note that cause and effect still moves from people to finance, but the arrows point downwards and not upwards.

“We have a management model that is well suited to dealing with turbulence and rapid change. It enables us to act and reprioritize quickly so that we can fend off threats or seize opportunities,” states Bogsnes.

As a powerful measure of how employees have responded to Statoil’s translation rather than instruction approach, note that despite there being around 700 scorecards enterprise-wide, they are not mandated. “We have no detailed roll-out schedule. People are fed up with being on the receiving end of corporate ‘roll-outs’ again and again,” says Bogsnes. “Instead, we focus on teams that invite us. Not once did we put our foot in the door because ‘this is decided.’ It takes longer, it looks messier, but change becomes real and sustainable.”

We will return to Statoil in Chap. 11: How to Ensure a Strategy-Aligned Culture, where we explain how they have become a values-driven organization. More extensively, we discuss Statoil’s unconventional approach to management in Chap. 7: Aligning the Financial and Operational Drivers of Strategic Success, where we explain how Statoil has become “budget-free”—it has not prepared an annual budget since 2006—and how it has introduced a more agile form of forecasting. Moreover, we explain how these approaches to financial management work alongside the Balanced Scorecard.

Key Lessons from Statoil

There is much to applaud and learn from Statoil’s approach to cascading (and indeed its other managerial approaches). The conventional approach rarely leads to buy-in and is no longer fit-for-purpose in today’s fast-moving markets. Spending up to a year designing a “beautiful” suite of aligned scorecards is simply pointless, and smothers strategic agility.

Rather, identify the critical (and very few) objectives and KPIs that must be devolved and then empower teams to build their own scorecard systems that describes what they want to achieve over the coming period.

Team Discussions

An important watch-out here often leads to frustration. The deeper into the organization the scorecard is cascaded, the less meaningful the term strategy becomes. We’ve lost count of the amount of times we’ve sat through (and even led) “Strategy awareness/alignment” sessions at departmental/team levels and witnessed eyes gradually glaze over and then people divert their gaze to that refuge of bored minds—the smartphone.

At departmental/team levels, we prefer to talk about the purpose of the group. We discuss the sense of purpose of the organization as encapsulated in the mission (see Chap. 2: From Industrial to Digital-Age-Based Strategies), then, how the group relates with other parts of the organization and their own sense of purpose: what they want to achieve over the short and medium terms and then why and how. See also Chap. 12: Ensuring Employee Sense of Purpose in the Digital Age.

At this level, focus is on the short and medium terms (no more than two years, so perhaps aligned to a mid-term quantified vision) and makes little more than a cursory mention of the longer term or where the organization wants to be in five years. Few of the staff will relate to this timescale as they are focused on day-to-day operations—and please do not mention shareholder value as people at lower levels have no real influence over this and will not be enthused about making shareholders richer.

Once the department/team’s purpose is agreed, understood, aligned with that of the organization, and codified, it is important to quickly move to ensuring the interventions are in place (leadership support, HR, IT, etc.) to make it happen.

The sad fact is that no matter what is discussed in team meetings/focus groups, in most organizations, participants will believe nothing they say will be listened to and that nothing will change.

Bad Practice Example

One of the authors recalls doing a major project for an organization in which he ran focus groups in 18 departments (each of which had an enforced scorecard, which they took zero notice of). In every session, participants firmly stated that this was a pointless discussion because the senior leadership team never listened to them or did anything: but they did run similar exercises every two years or so, with a new and enthusiastic consultant.

With difficulty, they were encouraged to be forthcoming and provided lots of great (some amazing) ideas, which were subsequently submitted to the CEO. Two years later, the report was still sitting on his desk and no recommended interventions had been implemented. Still, the CEO raged about the failure of employees to contribute to the strategy. We guess he then ordered more focus groups.

Departmental Success Story

There’s a slight twist to this tale. Although the 18 departmental scorecards gradually disappeared, along with the parent at the organizational level, one of the departmental heads was enthusiastic about the scorecard concept (having used it successfully in a previous company). He called one of the authors to help him develop a Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard. This was completed in three one-hour sessions. Two years later, it was the only part of the organization with a scorecard and had been devolved to team level at the request of the teams (in line with the advice from Bogsnes). The manager of this department informed the author later that the CEO had said to him, “Why are you the only part of the organization that ever mentions strategy?”

As well as leading to greater buy-in and ownership, allowing departments, and the like, to build their own scorecard systems transmits the message stressed by Bogsnes that senior management trusts their employees and believes in their abilities. Proper governance still ensures alignment, but guided by flexibility and empowerment instead of rigid imposition.

Structure

Structurally, the process for building cascaded Balanced Scorecard Systems is the same as for the corporate or top level. Based on the scorecard above, build a S trategic Change Agenda for the devolved level, followed by objectives, KPIs, targets, and initiatives. This does not change, except that, and for alignment purposes, a critical input is the work done at the level above.

Advice Snippet

Keep any mandated objectives, KPIs, and so on, to the critical few. For instance, for some organizations, this might relate to safety or environmental issues. If it’s mandated, be very clear why this is the case.

Focus the conversations on translating higher-level objectives into what the cascaded unit/department and so on wishes to achieve.

The deeper into the organization the scorecard is cascaded, lessen use of the term strategy, perhaps replacing it with sense of purpose (although still communicating the organizational strategy).

Focus on the midterm rather than the longer term, as this is more relevant and triggers a greater sense of urgency.

Pay attention to the capabilities the unit, and the like wish to develop as this opens up developmental opportunities for staff, which strengthens the likelihood of buy-in.

Make sure that agreed interventions that are required by levels that are more senior actually happen.

Alignment and Synergies

As stated earlier, alignment and cascade are not the same thing—although cascading is a central plank. Whereas cascading implies a downward motion, alignment is more multi-directional, so horizontal or matrixed, or even across partnerships (we explore partnership alignment in Chap. 13: Further Developments, Driving Sustainable Value through Collaborative Strategy Maps and Scorecards). Alignment also encompasses capabilities, such as for human and information capital (see Chap. 12: Ensuring Employee Sense of Purpose in the Digital Age).

Furthermore, and as Ionescu comments, alignment is also about the strategic dialogue, “which allow the ideas, opinions and suggestions to bubble-up from the individual level to the departmental level and from here to the organizational level.” Returning to theme of Chap. 4, Strategy Mapping in Disruptive Times, alignment might be more quantum mechanics than Newtonian.

Alignment: Using the Balanced Scorecard to Create Corporate Synergies

Of Kaplan and Norton’s canon of five books, the one that has received the least attention is book four: Alignment: Using the Balanced Scorecard to Create Corporate Synergies, [1].

This is a shame, as here they provide a very useful framework for driving alignment and, from this, synergies across the enterprise, both vertically and horizontally. Particularly powerful is the enabling of synergies within even the most diversified organization.

Strategy Maps and Diversified Organizations

We will pause here to make an observation on developing Strategy Maps for diversified organizations. Over the years, we have received questions many times on how to do this, as it proves to be a difficult challenge. The answer is simple—don’t.

A Strategy Map describes the value proposition to a specific set of customers, often served by a strategic business unit. In a diversified organization, there will be very different customers with very different value propositions, so the required objectives will also be diverse. In such cases, it is better to create separate scorecard systems. That said, and what was clever about Kaplan and Norton’s recommendations was that this does not mean that scorecard thinking cannot be applied at the corporate level of a diversified organization. However, a Strategy Map is not deployed.

Enterprise Synergy Model

In the Kaplan and Norton model, the four scorecard dimensions remain the same, but the naming is changed. Rather than perspectives, we have synergies; so, for example, the “Financial Perspective” becomes “Financial Synergies.”

In addition, the overriding questions that support conventional perspectives are different. Whereas for the classic scorecard we ask, “How do we create value in the eyes of shareholders/funders” here, the question is, “How can we increase the shareholder value of our Strategic Business Unit (SBU) portfolio?” For instance, creating synergy through effective management of internal capital and labour markets. The point here is that the enterprise level company is the funder of SBU operations, so it should look to allocate capital that drives collective value, perhaps by funding a shared services organization or common ERP system.

A more significant difference is for customer synergies. Here, the corporate centre, if you will, is not seeking to deliver a value proposition to a customer segment to secure revenues. The enterprise owns the SBUs—who obviously cannot choose to defect to a competitor. So here, the focus is on “How can we share the customer interface to increase total customer value?” Cross-selling is one way to do this.

For internal process synergies, the question is, “How can we manage SBU processes to achieve economies of scale or value chain integration?”- A shared services centre is one example. At learning and growth, we ask, “How can we develop and share our intangible assets?” so here, we look at areas such as common IT systems, leadership development programs, common values, and so on.

Driving Out Complexity

As much as anything, this model speaks to the importance of driving out complexity. Increasing layers of complexity accompany any organizational growth. Oftentimes, the original value proposition of the firm—which provided the success that enabled growth in the first place—gets diluted, and even lost, in the day-to-day battles of managing a larger organization. The sense of purpose is forgotten.

As an aside, one of the authors of this book once worked with a small, and very successful, organization that was about to set off on a trajectory of significant growth. The advice given was to frame the original Strategy Map and hang it on the CEOs wall so that the organization would always remember what made them great in the first place.

Why Simplicity Matters

Continued research by firms such as the US-headquartered The Hackett Group, with which one of the authors has enjoyed a two-decade-long working relationship, has repeatedly shown that the most effective way to reduce complexity is through standardizing, automating, and simplifying core processes. This makes it easier to adjust to all types of business change.

In the 2009 book, The Finance Function: Achieving performance excellence in a global economy, written by one of the authors, Jodiann Hobson, then Senior Business Advisor, The Hackett Group (now Principal Business Architect for the Australia-based Westpac Group), made this observation on how world-class finance organizations had managed to reduce costs significantly through driving out as much complexity as possible. Being world class (according to Hackett’s assessment criteria) also meant they were simultaneously delivering greater value to their internal and, where appropriate, external customers. “World-class companies have managed to reduce finance cost (as a percentage of revenue) despite the increased complexity and volatility of their operating environment – this is through their laser focus on continuous improvement and investment in standardized processes and technology,” she says [2]. Hackett research finds that the same principles of standardization, and so on, hold true for other support functions such as IT, HR, and procurement.

The purpose of including these observations here is this: the digital age will be increasingly global in nature and characterized by significant complexity—markets, customers, processes, employees, and technology. If organizations are to be agile and adaptive in strategy execution, they will need to ensure that this is not constrained by complexity: be that structure, policies, or fractured processes.

Whether diversified or not, organizations can use the thinking of the Kaplan and Norton Enterprise Synergy Model to drive greater value to customers, while still maintaining the required cost position. Much of this thinking might be applied to the initiatives chosen to appear on the corporate-level scorecard, which might then be cascaded to lower-level units. This might be particularly impactful within the learning and growth perspective.

Parting Words

Nevertheless, as Hackett research has uncovered, the key is to know when some level of complexity is still required for a competitive advantage. Alignment is essentially about getting collective focus on an agreed set of outcomes. Given the dynamic nature of markets, organizations, and people, this will always mean the acceptance of complexity and the dexterity to respond.

As with building the Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard, when driving out complexity, take heed of the further words of Professor Albert Einstein, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

Panel 1: Exception to the Rule – When Instruction Makes Sense. Saatchi & Saatchi Case Illustration

In the mid-1990s, the communications agency Saatchi & Saatchi Worldwide was on the brink of bankruptcy, and a new Chairman and a new CEO were recruited to drive an aggressive turnaround. A Strategy Map of just 12 objectives and a Balanced Scorecard of 25 KPIs was created for the corporate level.

All 45 country-based business units had to work with this system (with some modifications in targets, to reflect local conditions) but scorecards were not created at any lower level. The 45 units rolled up to 11 regions, which then got consolidated to make the worldwide enterprise scorecard. Performance was typically discussed from a regional perspective.

Now, the reason why Saatchi & Saatchi purposefully did not create a large suite of scorecards or even provide some degree of autonomy in unit-level scorecards was relatively simple.

In the decade or so preceding their financial woes, the organization had grown through aggressive acquisitions across the globe. Each country-based acquisition was essentially allowed to continue as before, but under the Saatchi & Saatchi brand. As a result, there were basically 45 different organizations, with very different processes, policies, and cultures.

When deploying the Balanced Scorecard System to drive transformation, the new executive leadership team decided to create a new structure that drove common practices, processes, and so on, enterprise-wide. Moreover, recognizing that many different cultures were operating within the organization, the people and culture perspective (its version of learning and growth) included just one objective, “One team: One dream: create a rewarding, stimulating environment where nothing is impossible.” The goal being to forge a common culture.

In short, the organization did not cascade, and so did not provide the autonomy for devolved units to build their own scorecard systems because there was a pressing need to drive discipline around commonality in processes and culture.

For an organization that was on the brink of bankruptcy, this was a sensible choice. As we explain in Chap. 10: How to Ensure a Strategy-Aligned Leadership, different strategies often require different leadership styles and, sometimes, a period of “instruction” is required, but always over the shorter term. It is not sustainable over the longer term—especially when the organization is no longer in danger of extinction.

Self-Assessment Checklist

The following self-assessment assists the reader in identifying strengths and opportunities for improvement against the key performance dimension that we consider critical for succeeding with strategy management in the digital age.

Please tick the number that is the closest to the statement with which you agree | ||||||||

7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

My organization has a very good process for cascading strategic objectives | My organization has a very poor process for cascading strategic objectives | |||||||

Strategic objectives are generally set by the individual units/teams | Strategic objectives are generally enforced in a top-down fashion | |||||||

When setting team objectives, we closely consider the “sense of purpose” of the team—what they want to achieve | When setting team objectives, we do not consider the “sense of purpose” of the team—what they want to achieve | |||||||

Generally, units/teams have fully bought in to their objectives/KPIs | Generally, units/teams have not bought in to their objectives/KPIs | |||||||

We have very well-established processes for gaining synergies across the organization | We have very poor processes for gaining synergies across the organization | |||||||