When we began our quest for the finest cup of coffee that we could produce, we had no idea that we would need to immerse ourselves in the story of coffee—the history, agriculture, and politics of its growth. But, to understand the core of the cup, we found that we did need to have a basic comprehension of the where and why of the bean—particularly since we wanted to tie the product we would be selling to our social consciousness.

As a major agricultural export for many impoverished (and now developing) countries, coffee has historically been traded on the backs of the poor and disenfranchised. Colonial powers blossomed through the enslavement of native workers throughout Indonesia, Africa, and Latin America. Coffee has not had a pretty history. So, although this history has created the future, our interest is in the more recent fair and equitable turn that specialty coffee trading has taken.

Like many foods with a long history, coffee comes with varied and somewhat questionable tales of its origin and many myths associated with its global reach. However, one fact seems clear: coffee is indigenous to Ethiopia. It is believed that its name comes, in part, from the particular area of the country, Kaffa, where it is native as well as from kafa, the Ethiopian word for it. The most oft-told tale is that its energizing effects were first discovered in the mid-800s by an Ethiopian goatherd named Kaldi, who noticed that after eating the berries from local trees his goats danced and caroused in a lively fashion. He joined them in the feast and quickly found that he, too, could mimic their enthusiastic partying. Nearby monks took to the habit and turned the berries into a drink that helped them concentrate on their religious studies. With this mythical beginning coffee began its travels around the world—first as a drink used in religious practices, then through broad medicinal use, and finally as a social drink firmly established throughout the Middle East.

Coffee consumption and culture were an integral part of daily life in Ethiopia long before its adaptation by other cultures. It wasn’t until the 1600s that coffee began its move from the Muslim world and took its place in European societies as coffeehouses opened across the continent and the United Kingdom. Unlike almost everything else in “polite” society, coffeehouses were open to all classes of people, and this affected their acceptance as well as their prohibition. The energizing effect of the drink only heightened vigorous political and social intercourse, which, in turn, was often the seed of social unrest. So, while the ordinary man enjoyed the freedoms generated by the sociability of the drinking house, authorities frequently found coffeehouses to be the setting for seditious behavior and used various tactics to suppress them. However, over generations, coffee drinking and coffeehouses became so firmly entrenched throughout the world that, despite taxation, prohibition, royal decree, abolishment, and censorship, they persevered as the meeting place of choice for the general population. And, today, we are seeing select specialty coffee bars as both the meeting place and the magnet for socially conscious activists.

Although Ethiopia is the birthplace of coffee, coffee trees are now found in a number of regions between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. In fact, almost all of the world’s finest coffees come from three growing regions: East Africa/Arabia, the Pacific/Indonesia, and the Americas. All of the coffee-producing countries in these regions share a commonality: a mountainous, subtropical climate and an equatorial position, both of which combine to produce superior coffee beans. Within these areas, specialty coffee is most often cultivated at higher altitudes, usually from 3,500 to 6,500 feet, because it is generally felt that the higher the altitude, the denser, more deeply flavored the harvested bean. No matter the area, coffee farming is a difficult, arduous, and financially challenging business.

To ensure that we fully understand the scope and intensity of the production of specialty coffees, we frequently send our leading baristas to the place of origin during harvest. During this indoctrination they observe exactly how quality beans go from tree to cup so that they can convey the depth of the specialty coffee program to joe customers. It is important that we all understand that coffee is much more than just a commodity to be consumed; it is the means of survival for vast numbers of marginal lives across the globe. During these visits, our baristas walk among the trees, tasting the ripe cherries, interacting with the farmers and pickers, and learning from the bottom up.

Although coffee trees can grow to great heights when left on their own, they are usually pruned to a manageable height when farmed. Usually no more than ten to twelve feet tall at their highest, the coffee trees or bushes are generally covered by larger shade-producing trees to protect them from intense, direct sunlight during the day and inclement weather at all times, particularly killing frosts. Additionally the shade cover provides an even temperature through the cooler evening hours, giving the trees steady warmth. Often the shade trees are fruit-producing, which also offers another source of income for the farmer. Almost all coffee trees are young, under twenty-five years old, to ensure vigorous output, as older trees lose much of their productivity.

As important as shade-grown coffee farming is, specialty coffees can also be grown in nonforested areas. These regions were originally grasslands with few shade trees in their landscape. For instance, Brazil’s Cerrado (in the state of Minas Gerais) produces much-esteemed specialty coffees without the canopy of shade trees. As in life, it seems there is always an exception in coffee growing.

The shade-grown method of coffee farming is known as an agroforestry structure—the primary product, coffee, is treated as an underbrush to the shade cover, which is most often a combination of fruit trees, perennial large-leafed banana plants, and hardwood trees. This method provides protection from soil erosion, maintains favorable and stable temperature and humidity, replenishes the soil with rotting organic matter from the plants and trees, and offers a home to beneficial insects. In fact, this traditional approach to coffee farming is considered one of the most ecologically anchored and environmentally favorable agro-ecosystems. Little did we know that by choosing specialty coffee, joe would be playing a part in sustainable agriculture.

Coffee is grown on a number of differing types of farms. The largest, worldwide, are estates also known as fincas (or fazendas), estancias, or plantations, depending upon the locale; they are usually a large landmass with multiple buildings and on site processing run by an individual or a family, sometimes an extended one. These operations generally offer very consistent supervision of the farming and the processing but also face devastation in years of bad weather or local upheavals when an entire expansive harvest can be lost. Coffees from estates will often offer high-quality, defined, and recognizable flavors in a roasted bean. However, there exist privately owned estates that lack the care or craftsmanship required to properly prepare and sort their harvested cherries. The simple fact is that many estates produce coffee of superior quality while others do not. The next largest type would be farm-cooperatives, which are associations of farmers joined together in their common interest. The main drawback to the cooperative method of selling coffee is that an extremely desirable bean may be combined with inferior beans, resulting in less reward for the more passionate farmer who has produced it. There are a number of coffee cooperatives that are exemplary in sorting their coffee cherries and have a high degree of craftsmanship. A case in point is the Konga Cooperative in Ethiopia’s Yirgacheffe region. Finally, there are the small farms owned by an individual or a family where the coffee can range from exceptional to ordinary. On these small farms, it is possible for roasters to work one on one with the grower to develop phenomenal coffees. However, in a continuing search for the best possible bean, the specialty coffee roaster works with all types of growers.

Almost every coffee-growing region has a single harvest each year, but there are exceptions. For instance, Colombia has two harvests, consisting of one main crop and another usually smaller one called mitaca or traviesa (fly-crop); however, the Santander, Boyaca, and Sierra Nevada Colombian coffees are only harvested once, during the second semester of the year. (The first semester begins in April and ends in July while the second begins in September and ends in December.)

In the specialty coffee market, the goal is to convey the dried beans to the roaster as quickly as possible so that the beans can be prepared for the consumer when the level of freshness and vibrancy is at its highest. Therefore, just as a buyer visits a farmers’ market for of-the-moment produce, seasonality is perhaps the most potent selling point of an artisanal coffee. Again, there are a few exceptions, with the Monsooned Malabar and Aged Sumatra coffees rested and then aged for many months and sometimes years. At joe, as well as at other top specialty coffee bars, primarily seasonal coffees are served.

Currently, most specialty coffees come from growers in Nicaragua, Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Yemen, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Peru, Panama, Burundi, Tanzania, and Kenya. All of the estates, cooperatives, or farms support sustainable and, often, organic agricultural practices, with the farmers realizing maximum profit for their efforts through the Direct Trade system (see page 13). Through this system coffee roasters, such as Ecco/Intelligentsia, our current joe roasters, buy their green beans directly from the farm, eliminating the traditional buyers and giving the roasters firsthand knowledge of the farm’s practices. This system is somewhat different from other socially conscious and certified methods such as Fair Trade (see page 17) because of the straight line from farm to cup, building strong, enduring relationships among all of the participants along that line. Ecco/Intelligentsia has even trademarked the certification Intelligentsia Direct Trade, which indicates the standards (including its relationship with farmers) set for its coffee. Other roasters generally have similar programs to give them greater control over the quality of the coffee and to make sure that specific concerns about environmental and social issues are met. To the point, when purchasing green coffee, a fine quality roaster targeting ethical principles intends for the coffee farmer to receive the same international accolades and recognition as the proprietor of a vineyard would receive from the wine industry.

To this end, in the early 2000s a few dedicated specialty coffee buyers and roasters created a program called Cup of Excellence. The program was spearheaded by George Howell, a Boston-based pioneer in the specialty coffee business; Susie Spindler, an early promoter of artisanal coffees; and Silvio Leite, a Brazilian coffee expert. Funded by the International Coffee Organization, the International Trade Center, and the United Nations Common Fund for Commodities, the project grew out of the founders’ frustration with the lack of appreciation for high-quality Brazilian coffees among North American specialty coffee buyers. It has grown to become an internationally known, strictly ruled yearly competition that chooses the finest coffee produced in a country. A jury of international coffee experts selects the winning coffees, and the final stars of the crop are auctioned via the Internet to the highest bidder. Coffees deserving of the award are extremely rare; they must be perfectly ripe when picked and exhibit a well-developed body, a pleasant aroma, and a lively sweetness, qualities only found in carefully grown, exemplary coffees. As with wine, each Cup of Excellence winner manifests its own signature flavor redolent of the terroir in which it is grown and is managed throughout the growing and drying process in a manner that enhances its unique characteristics.

Through the Cup of Excellence program, an individual grower is shown the importance of quality in relation to price, as the auctioned coffee always enjoys a high premium. And, more importantly, the grower receives 85 percent of the auction price. This esteemed program advocates cooperation among every level of international specialty coffee production and sales and promotes alliances among individual growers in a country.

All specialty coffees, no matter their homeland, are Coffea arabica, the seed of a cherry-like fruit produced by a perennial evergreen tree. (There is another widely grown coffee, Coffea canephora, more commonly known as Coffea robusta, that not only produces far greater yields than arabica but is also resistant to disease. However, it is only used for large-scale commercial coffee production and is rarely found in specialty coffee). To produce a fine coffee, the cherries must be handpicked at the perfect degree of ripeness, a labor-intensive job. The landscape is fairly rugged and uneven, the undergrowth is thick, the cherries are of a differing degree of ripeness on each branch, and, as with most fruit trees, the fruit grows randomly along the branches. The picker tries to lift only those cherries that are at the height of their ripeness, ruby red and Bing cherry–like, although mistakes are easily made and less ripe cherries often make it into the picker’s basket. Both underripe and overripe cherries will be sour, with the underripe also quite astringent and the overripe tasting salty and fermented—not desirable flavors when creating a fine coffee. We have visited farms during harvest and can assure you that we came away with a deep admiration for the farmers and workers and clearly understood why premium coffee demands a premium price.

After picking, the cherries require extensive processing to get to a marketable state. There is an ancient process now known as the natural/dry process whereby the picked cherries are dried in the sun before processing begins. Drying takes approximately two weeks, and the cherries are constantly raked to prevent mold from forming on the moist fruit. When the cherries are completely dry, the outer skin, pulp, and parchment are removed. Because this natural method requires a climate that is normally extremely hot and arid, it is mostly done in Yemen, Ethiopia, and areas of Brazil. However, since it is thought that the dry process yields coffees with deeper, more rounded body and less acidity, a number of Central American producers have been experimenting with producing natural/dry processed coffees. The Peterson family of Panama’s legendary Hacienda La Esmeralda and Aida Battle, owner of El Salvador’s award-winning Finca Kilimanjaro, have been branching out, processing their coffees using this traditional method.

DIRECT TRADE

Direct Trade is a term used by coffee roasters who buy straight from the farmers, cutting out the traditional middleman buyers/sellers. We believe Direct Trade is the best model because it builds mutually beneficial and respectful relationships with individual farmers or cooperatives while paying the highest price for exceptional beans and demanding sustainable environmental and social practices.

CRITERIA:

> Coffee quality must be exceptional.

> The verifiable price to the grower or local co-op—not simply the exporter—must be at least 25 percent above the Certified Fair Trade price.

> The grower must be committed to healthy environmental practices.

> The grower must be committed to sustainable social practices.

> Ecco Caffè representatives must visit the farm or cooperative village at least once per harvest season.

> All participants must be open to transparent disclosures of financial deliveries back to the individual farmers.

Perhaps one of the strangest, costliest, and most coveted of all coffees is kopi luwak or civet cat coffee. Found in the Philippines and Indonesia, it is created when coffee cherries are eaten by the civet cat, passed through the digestive tract, and then excreted, essentially as processed beans. The seeds are fermented by the stomach acids and enzymes, which supposedly gives the coffee brewed from them an incredibly smooth, velvety flavor with no bitterness on the palate. The beans are washed thoroughly, sun-dried, and very lightly roasted. Only kopi luwak found in the wild is in demand, and it is quite rare. The retail cost per pound is two hundred to three hundred dollars.

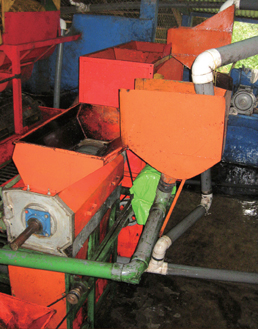

In all other areas, once the cherries have been picked, they must be washed and sorted. As they make their way through water-filled canals, underripe cherries will rise to the top, and sorters will pick out diseased, damaged, or overripe cherries by hand. The next step is to squeeze the seed from the fruit, a system called depulping, which can be done by hand-operated machines on small farms or by large-scale machinery in larger processing plants.

FAIR TRADE LABELING:

Fair Trade is an organization that aims to help farmers in developing countries make better trading conditions and promotes sustainability. The movement advocates the payment of a higher price than the commodity market to farmers and to help improve their quality of life as well as their environmental standards in farming.

CRITERIA:

> The coffee was produced by a member of a democratically run cooperative.

> A minimum of $1.31 per pound of green, unroasted coffee was paid to the farmer for conventional coffee, and a minimum of $1.41 was paid for Certified Organic.

> The producers had access to preharvest credit.

> Certification was done by a recognized third-party authority (Transfair USA in the United States).

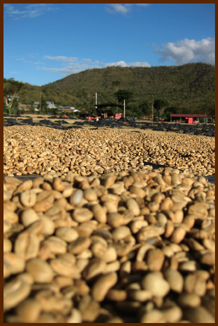

After depulping, the seeds are still covered by a thin layer of mucilage, which must be removed. This can be done by one of three methods: pulped natural, aqua-pulping, or washed. The first method allows the beans to dry naturally in the sun, and with the second, the beans are machine-scrubbed to remove the covering. The third, whereby the beans are steeped in water to create fermentation, is the preferred method for specialty coffee beans as accurate fermentation ensures perfectly balanced body and fruit in the roasted bean. After fermentation, the seeds are washed to eliminate any lasting mucilage cover and are then laid out on concrete slabs or raised mesh screens to dry in the sun. All during the drying process, the beans are frequently raked over the slabs or tossed on the screens to generate uniform drying. They can also be mechanically dried by spinning them in rotating drums at a fairly constant low temperature.

As the seeds dry, a parchment-like film blooms. This serves to protect the drying coffee until it reaches the appropriate 12 percent level of humidity. If the beans do not reach the desired level of humidity, they can develop a variety of problems, such as mold, during shipping and will be unusable. Yet, when the beans are overdry, they may easily crack, and the finished flavor will be dull and woody with indistinct acidity, not desirable qualities at all.

To ensure quality flavor the dried beans must rest in their parchment covering. This dormant process can take thirty to sixty days. During this resting period, the humidity equalizes throughout the batch and the beans are rendered more resistant to breakage and damage from variations in humidity and external pressures. When beans are evaluated too early in the resting period, they often display grassy or vegetal characteristics that do not give a clear example of their final, fully rested state.

BIRD FRIENDLY CERTIFICATION (also Shade Grown)

Bird Friendly certification attests to the fact that the coffee farm has not cut down the trees and plant life that create the natural habitat for birds and the whole ecosystem. It is important to note that specialty level coffee is, by default, shade grown, because it requires a certain amount of shade throughout its growth to properly ripen.

CRITERIA:

> Certification is done through the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center.

> The coffee is shade-grown in a forest-like habitat friendly to migrating and local birds.

> The coffee is grown on organic farms in Latin America.

> No chemical pesticides are allowed.

After rest, the remaining parchment-like covering must be removed. This is accomplished in a deparching/hulling machine. Then, again, the beans must be sorted, usually by machine, to give a final cleaning as well as to remove any remaining defects. Finally, the beans are hand-sorted to eliminate those that have undesirable color, are broken, or have any previously undetected blemishes. This final sorting is the most important as, with the proverbial one bad apple spoiling the barrel, a few bad beans can completely diminish the excellence of the cup.

Throughout the drying and cleaning process, the beans may or may not be tested for quality through “cupping,” a standard method of quality control (see pages 30 and 38). Optimally, sample cuppings should be done at the farm with freshly harvested beans. In part, this allows the farmer to fully comprehend the flavor profiles desired by a specialty roaster. Unfortunately, this practice does not happen often. Generally the responsibility of tasting and qualifying is left to agronomists, buyers, or “cuppers” at a cooperative or processing source. However, in the last decade, due to the growth of the Direct Trade movement, we have seen a trend whereby the more progressive and quality-focused farms are instituting quality control programs on site.

In addition, we have seen a growth in cooperation between farmers and green-bean buyers that involves them tasting their beans together.

All of the discrimination that goes into selecting fine quality beans also goes into selecting and processing decaffeinated beans. In addition, the search continues for improved methods of removing the caffeine. Because of the time and effort involved in creating it, decaffeinated coffee carries a wholesale cost substantially higher than nondecaffeinated beans, but this cost is rarely reflected in its retail price. All of the decaffeinated coffee that we serve at joe has been carefully selected and decaffeinated through either the water process or the German/European (MC/methylene chloride) process. Both processes use the indirect method of decaffeinating whereby the activated agent does not come in direct contact with the coffee beans. The decaffeinating process known as the direct method is never used in the specialty coffee business.

During the decaffeinating process the green coffee beans are soaked in large tanks of water, which releases the caffeine from the pores of the beans. The soaking water is drained from the tank and treated with a chemical agent to extract the caffeine. Then the caffeine and the chemical are removed from the water, and the beans are reintroduced to the solution to drink in the flavors suspended in the water. This process uses activated charcoal to cleanse the caffeine from the water. All decaffeinated coffee has some caffeine remaining; the amount can range from negligible to thirty-five milligrams per cup. Whether decaffeinated or not, after all of the processing has occurred and specialty coffee roasters have made their selections, the beans are then bagged, most often in 132-pound jute or sisal bags. However, before bagging, our roasters, Ecco/Intelligentsia, take one extra step to maintain the integrity of the green coffee. Sorted and hulled beans are carefully packaged at origin in plastic grain-pro inner liner bags that protect the green beans from moisture transfer. This extra measure guarantees that the delicate flavors, nuances, and vibrancy of the green beans remain. The jute or sisal bag then adds an extra layer of protection to our select beans.

There is, as always seems the case with coffee, one exception to this packaging process. Some reserve lots from Kenya and the Cup of Excellence program are vacuum-packed in Mylar bags at origin and transferred to cardboard boxes for shipping. It is felt that vacuum-packing offers first-rate protection, ensuring the exceptional flavor and shelf life of green coffee beans.

Whether bags or boxes, appropriate packaging is extremely important, as the beans must be protected from heat, light, oxygen, moisture, and contaminants in the air during shipping. With the most common packing and shipping method, the green bean–filled bags are placed in metal shipping containers and begin their journey to the cup. After the long processing period, the time it takes for the beans to travel to the roaster and onto the specialty coffee bar is relatively short—usually no more than a month. And, as much care will be committed to the roasting as has gone into the growing and processing.