Some of Phil Camill’s trees are drunk. Once, the black spruce trees…in northern Manitoba stood as straight and honest as pilgrims. Now an ever-increasing number of them loll about leaning like lager louts. The decline is not in the moral standards of Canadian vegetation, but in the shifting ground beneath their roots.

—Gabrielle Walker, “Climate Change 2007: A World Melting from the Top Down” (2007)

THE ICE BENEATH OUR FEET

The Nature of Permafrost

A hidden world of ice lies concealed in soil beneath our feet near the poles and in high mountain valleys. Permafrost, or perennially frozen ground, underlies nearly a fifth of the world’s land area.1 But this netherworld is also rapidly changing as rising temperatures rapidly defrost the permafrost, sometimes inadvertently uncovering once-buried treasures. Hunters or herders in remote parts of northern Siberia occasionally stumble across long, slender mammoth tusks poking out of the tundra. The newly exposed mammoth ivory has fueled a lucrative trade in recent years, spurred by the combined effects of thawing permafrost, the ban on imports of African elephant ivory, and a growing demand from China, Japan, and Korea, where the material is carved into decorative objects and used for personal seals.2 The commercialization of mammoth ivory provides income for indigenous people, but could also obstruct scientific analysis of valuable data on ancient environments contained within the fossils. On the other hand, ivory, once exposed to the elements, disintegrates within a few years and will be lost forever unless quickly salvaged. Deicing permafrost not only unlocks buried treasures; its effects sweep across the Arctic. The meltdown tilts trees at crazy angles, topples cliffs, buckles roads, collapses buildings, crumbles shorelines, transforms the landscape and hydrology, and could also alter the regional ecology. But these visible changes may be just the tip of the iceberg. Will we face a carbon apocalypse, as some apprehensive experts have warned? Is decomposing permafrost a ticking carbon time bomb poised to unleash yet more methane into our increasingly heavy load of atmospheric greenhouse gases? Will enough methane bubble up from soggy Arctic soils and the seabed to hasten the ongoing warming trend in a positive feedback loop? What does the thawing permafrost portend for the Arctic and the world beyond? This chapter delves into some of these questions.

Temperature, rather than ice content, defines permafrost: a soil, sediment, or rock in which ground temperatures stay below 0°C (32°F) for at least two consecutive years. Therefore, climate conditions determine the geographic distribution of permafrost. Frozen ground exists worldwide at high latitudes, at high altitudes, and on continental shelves surrounding the Arctic Ocean (fig. 3.1). (Most marine permafrost dates to the last ice age, when a much lower sea level exposed shallow portions of the continental shelves to frigid temperatures. The frozen soils were subsequently drowned when the ice sheets retreated and sea level rose.) Today, the southern limit of most Northern Hemisphere continuous permafrost, where over 90 percent of the area remains frozen, roughly coincides with average yearly air temperatures of −8°C (18°F).3 Discontinuous permafrost (underlying between 50 and 90 percent of an area) develops where average yearly temperatures are −1°C (30°F).

FIGURE 3.1

In the Northern Hemisphere, the permafrost layer thins progressively from north to south and ultimately grades into a patchy, discontinuous zone near its southern boundary. Soil also freezes seasonally wherever ground temperatures remain below freezing for several weeks. Asia boasts the greatest expanse of permafrost—in northeastern Russia, including Siberia; the Tibetan Plateau; northeastern China; and parts of Central Asia. Permafrost also extends over most of Alaska and vast areas of northern Canada and Scandinavia. Maximum permafrost thicknesses range from 1,500 meters (5,000 feet) in northern Siberia to around 400 to 700 meters (1,575–2,300 feet) thick in North America.4 In the Southern Hemisphere, it occupies nearly all of the ice-free regions of Antarctica, islands near Antarctica, and the southern Andes. It also occurs at very high elevations at low latitudes.

In areas of yearlong subfreezing temperatures, some of the frozen ground does not thaw completely in summer. Over time, a permafrost layer develops, gradually thickening each year. The active layer freezes in winter, thaws in summer, and extends about 1 to 10 meters (3.3–32.8 feet) down from the surface into the permafrost. It forms during the short, cool summers. Unfrozen layers or lenses, or taliks, may lie interspersed between permafrost and the base of the active layer. The active layer thins toward the poles or high elevations, and also wherever it is covered by an insulating, thick winter snowpack or thick summertime vegetation. It represents an exchange zone where heat travels back and forth between surface and permafrost, gases and water are transferred between atmosphere and permafrost, and nutrients and water are provided for vegetation.

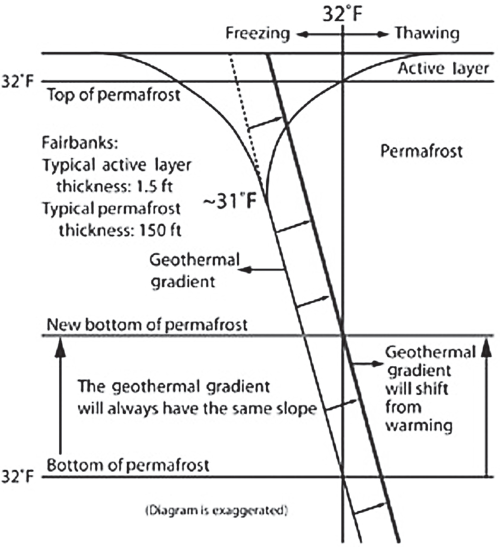

Permafrost thickness exists delicately balanced between the near-constant upward heat flow from the Earth’s interior and heat propagating downward from the surface. The permafrost layer ends at a depth where the temperature rises above freezing (fig. 3.2). Temperatures from the interior rise at a rate known as the geothermal gradient, due to the Earth’s internal heat.5 The flow of heat from below depends on the thermal properties of ice, soil, or rock, and on local geology, being higher near active volcanoes or regions of mountain building than in geologically quiescent areas.

FIGURE 3.2

Short-lived and longer temperature perturbations at the surface affect downward-flowing heat. Wide daily and seasonal temperature swings at or near the surface dampen downward to the depth of zero amplitude, around 10–25 meters (32.8–82 feet) below the surface, where temperatures remain constant year-round. Below this level, the geothermal gradient determines any further downward increase in temperature (fig. 3.2). Seasonal temperature variations are generally confined to the upper 20 meters (64 feet) whereas longer (decadal to centennial) temperature changes penetrate to greater depths—100 meters (328 feet) or more.

A thermal disturbance instigated by a climate change propagates downward until it merges at depth with the undisturbed geothermal gradient (fig. 3.2). It also shifts the temperature-depth curve toward higher (or lower) temperatures. As a wave of surface warming gradually moves downward, the top of the permafrost layer begins to thaw. The higher surface temperature lowers both the top of the permafrost layer and the depth of zero temperature amplitude. This shifts the temperature-depth curve toward the right in figure 3.2. The base of the permafrost layer rises because the base intersects the freezing point at a higher elevation under the surface. This causes the permafrost layer to shrink from both top and bottom.

A sensitive thermometer, such as a thermistor or thermocouple, lowered down a narrow-diameter borehole measures soil temperatures at different depths. Temperature profiles vary from place to place because the internal heat flow and temperature history may also vary locally. To reconstruct the thermal history of a given locality, the best match is sought between observed borehole data of downwardly propagating temperature changes and mathematical models of likely temperature histories. Inasmuch as the geothermal gradient remains constant over millennia, any deviation from this theoretical temperature profile at depth represents pulses of recent surface temperature changes traveling downward. The Global Terrestrial Network for Permafrost (GTN-P), organized in the 1990s and managed by the International Permafrost Association, monitors changes in active-layer thickness and permafrost temperatures.6 A network of over 1,000 boreholes collects ground temperature measurements in North America, the Nordic countries, and Russia.

Some of the earliest boreholes drilled during the 1980s by Arthur H. Lachenbruch and his colleagues from the United States Geological Survey in Alaska revealed temperature anomalies suggesting a twentieth-century regional warming of around 2° to 4°C (3.6–7.2°F).7 Warming signals from more recent boreholes throughout the Arctic further support an increasingly balmy northland (see the following section).

As Ground Freezes

If you want to dig a ditch in the Arctic, you’d better bring more than a shovel.

As temperatures plunge below 0°C (32°F), pore ice—water trapped in pores between soil or sediment grains, pebbles, and rocks, and within narrow rock fissures—solidifies. Unlike most liquids, water expands around 9 percent upon freezing, exerting a pressure that pushes soil particles aside.9 Soil volume expands still further when an external water source builds up ice. The growth of buried ice masses buckles soil upward. Needle ice is one of the earliest types of ice to form in late fall or in winter. Narrow ice needles appear as water in soil pores freezes, drawn upward by capillary action toward the cooling surface. With continued growth, ice needles cluster into vertical columns.10 The force of crystallization pushes small soil particles aside and upward. This process loosens soil, making it more susceptible to soil creep and erosion on slopes, and creates frost heave.11

Frost heave develops as water moves along as extremely thin films between soil particles. Presence of a thin water film is more effective than dry ice expansion alone. Ice initially freezes within tiny soil or sediment pores or in minute rock fractures. Premelted water (a thin molecular film of water adhering to particles) coats surfaces between ice and soil, remaining stable well below the normal freezing point. Water migrates upward along these wet films and feeds a growing ice lens, or layer of buried ice, lying parallel to the surface. The enlarging ice mass in turn dislodges overlying mineral grains and thrusts soil upward forcefully enough to seriously damage roads, bridges, and buildings (see Building on Unsteady Ground, later in this chapter). Often, multiple bands of clear ice develop, sandwiched between ice-free soil layers. Frost heaving occurs optimally in soils of silt-sized particles (0.002–0.05 millimeters in diameter). Sand-sized grains (0.05–2 millimeters) are too coarse (water drains out too fast), whereas fine clays (<0.002 millimeters) are too impermeable. Other favorable conditions include a continuous supply of water, below-freezing soil temperatures, suitable cooling rates (a sudden freeze could halt ice lens accumulation), and a thick, insulating snow or vegetation cover to modulate freezing rates.

Ground ice also forms ice wedges and pingo ice (see the following section). Ice wedges—carrot-shaped ice masses up to 3 meters (9.8 feet) wide at the surface—taper to several centimeters across, some 10 meters (32 feet) below the surface (fig. 3.3a). When winter temperatures dip below −15°C (5°F), soil contracts and becomes brittle, cracking with a sharp noise and tremor. Water enters the contraction cracks during the spring thaw, but refreezes within a narrow, nearly vertical vein the following winter. Ice expansion (9 percent) widens the vein, shoving aside adjacent and overlying soil. The ice-filled vein, weaker than solidly frozen soil, breaks open again the following winter. This recurrent process, year after year, builds up quite large wedges. Vertical banding in the ice wedge marks the scars of repeated breaking and healing cycles. Sand may replace ice in dry or well-drained environments, creating sand wedges instead.

FIGURE 3.3

Characteristic landforms of permafrost regions:

(a) ice wedge (man is pointing at the wedge) (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers/CRREL, https://www.erdc.usace.army.mil/Media/Fact-Sheets/Fact-Sheet-Article-View/Article/476646/permafrost-tunnel-research-facility/); (b) polygonal networks and pingo (“A melting pino and polygon wedge near Tuktoyakuk, Northwest Territories, Canada,” by Emma Pike/Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Melting_pingo_wedge_ice.jpg); (c) thermokarst lakes (“Teshekpuk Lake, Alaska’s North Slope,” August 15, 2000, https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/6391/teshekpuk-lake-alaskas-north-slope; image courtesy of NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS, and the U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team); (d) solifluction flow in Alaska (B. Bradley/University of Colorado).

Ice is a powerful sculptor shaping the land, shaving mountaintops, carving valleys, and leaving behind multiple signs of its former passage, as the next chapter will amply illustrate. Although its underground work is subtler, the trained eye quickly discerns the unique features that typify permafrost terrain. Frost action creates distinctive landforms, such as patterned ground, pingos (fig. 3.3b), palsas, thermokarst (fig. 3.3c), and slope movement (fig. 3.3d).

Repeated freeze-thaw cycles modify the surface in characteristic ways. Conspicuous among these are the geometric forms collectively known as patterned ground, which include ice-wedge polygons and circles on gentle slopes and steps and stripes on steeper inclines. Ice wedges generally occur in intersecting networks of rectangular or hexagonal polygons 3 to 30 meters (10–98 feet) in diameter. At first glance, they somewhat resemble drying mud cracks or the hexagonal columns in cooling lavas (e.g., the Devil’s Causeway in County Antrim, Northern Ireland). However, unlike those, ice-wedge polygons result from contraction cracks in freezing ground (figs. 3.3a and 3.3b). Frost heaving often raises ridges surrounding actively growing ice wedges, producing low-centered polygons that may hold small thaw ponds in summer. By contrast, thawing or inactive wedge networks may form troughs into which surrounding material may slump. In this case, polygon centers may stand above their peripheries. Therefore, subtle height variations among polygonal arrays offer clues to their current status.12 Drier or better-drained ground may feature sand-wedge polygonal arrays instead.

The adventurous traveler can view some of these features underground, beautifully exposed in the Permafrost Tunnel, near Fairbanks, Alaska (see box 3.1).

The Permafrost Tunnel, operated by the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CCREL) of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers near Fairbanks, Alaska, affords a unique, up-close view of permafrost features.18 Excavated between 1963 and 1969 in permafrost 15 meters (49 feet) below the surface, the tunnel is approximately 110 meters long (361 feet), 2 to 2.5 meters high (6.6–8.3 feet), and 4 to 5 meters (13.1–16 feet) wide. A walk through the tunnel, the size of a mine or subway tunnel, feels like entering a time machine. An undisturbed cross section of silt, sand, and gravel up to 46,000 years old from the last ice age lines the walls. These sediments preserve abundant mammoth, bison, and horse bones, among other fossils. Still older gravels sit beneath, deposited when the first Northern Hemisphere ice sheets began to grow some 2.5–3 million years ago.

The roof of the tunnel exposes segments of an ice-wedge polygon that tapers downward along the walls of the tunnel into a typical carrot-shaped form (see fig.3.3a). The ice-age ice wedges no longer grow actively. During a past warm period, surface water trickled down into and cut across the ice wedges, eroding channels through which more water penetrated and carved out hollows. The water eventually refroze into thermokarst cave ice.

The successive strata within the tunnel record at least seven distinct episodes of past climate changes during and after the last ice age. Bands of peat indicate the tops of former active layers; interspersed ice layers represent the tops of the permafrost at those times. The tunnel also preserves two separate sets of ice wedges, ranging in age from 25,000 to 33,000 years ago at the peak of the last ice age, and 10,000 to 14,000 years ago near its termination. A thaw during the intervening missing period presumably separated the two sets.

Circular, slightly domed features, several meters across and usually bordered by vegetation, often occur on fairly flat terrain. These circles, generally smaller than polygons, typically form in fine-grained soils, occasionally ringed by stones that were emplaced through countless cycles of seasonal frost heaving. The churning action separates fine from coarse material, pushing stones up to the edges of the circles. Irregular clusters of hummocks, with shapes intermediate between circles and polygons, commonly populate the Arctic landscape as well.

Bench-like steps, or terraces, often run parallel to slope contours on steeper hills. Series of stripe-like vertical bands may appear on hillsides. These develop as moist soil slowly slides down over permafrost on slopes steeper than those harboring circles or polygons.

Large, circular to elliptical mounds often punctuate the permafrost landscape. Pingos typically stand 3–70 meters (9.8–230 feet) high and 15–450 meters (49–1480 feet) across. Water injected under pressure from below creates these landforms. Upon freezing, the ice pushes up overlying soil, forming a mound similar to an intrusion of igneous magma that pushes up overlying rocks into a dome.13 Two different kinds exist. Closed-system pingos—more common in continuous permafrost, such as along Alaska’s North Slope and in northwestern Canada, develop as underground water under pressure forces its way upward and eventually freezes. Increasing ice accumulations from below project the ground upward into a small hill. Most of these occur in or near former lake beds.14 Open-system pingos, on the other hand, occur mostly in warmer, discontinuous permafrost—usually in valleys or on slopes where artesian water can flow downhill within unfrozen soil layers in the permafrost. Hydraulic pressure ultimately forces the water to the surface via natural cracks or channels. Near the surface, the water freezes into a subsurface lens and lifts up the overlying permafrost.

Palsas, like pingos, are small, ice-cored mounds that protrude above their environs. Smaller than pingos and with more variable shapes, palsas stand up to 10 meters (32.8 feet) high and 15–150 meters (49–492 feet) long. They generally occur in discontinuous permafrost. However, unlike pingos, palsas usually grow in wet, boggy, peaty soils. Growth begins where freezing takes place faster than in surrounding areas, due either to weaker insulation (e.g., a thinner snow cover) or greater heat loss. The bog supplies enough water to the upward-expanding lens, which bulges the surface up into a palsa. Eventually, the mound surface is disrupted, then melts and collapses, until the cycle is renewed nearby.

The ground, rock solid in winter, becomes mushy and unstable during late spring–summer thaw. Fine-grained soil and sediment, loosened by repeated heaving and thawing of frost, creeps slowly downslope by gravity, even on gentle slopes. Solifluction, the slow downhill movement of soil and sediment, creates festoons of tonguelike lobes and sheets (fig. 3.3d). Gelifluction is a form of solifluction in which the moving mass glides over a slick permafrost layer. Sometimes the ground gives way suddenly in a rapid, ribbonlike mud or earth flow.

Repeated rounds of extreme seasonal temperature fluctuations can crack bare rocks on steep slopes. Frost wedging and weathering enlarge the fractures until the rock shatters and collapses in massive rockfalls. Rocks thus eroded from mountain slopes accumulate at the base and in the valley. A rock glacier develops when the frost-shattered, angular debris blankets an ice glacier, or when permafrost ice seals empty spaces between rocky debris, or some combination of both. Regardless of the exact origin, rock glaciers, or ice/debris mixtures, creep slowly downhill within the permafrost domain.

Caving In

Because ground ice lies so near the surface, Arctic tundra is extremely sensitive to any surface perturbations that initiate thawing. These include regional warming, destruction of the vegetation cover by fire or human activities, or river incision, causing localized melting and ground subsidence. This creates a distinctive thermokarst landscape. Telltale signs include small, marshy hollows; hummocks; beaded streams; irregular drainage; and multiple-thaw (or thermokarst) lakes, often elliptical or elongated in shape.15 Tens of thousands of thaw lakes and depressions dot northern lowland permafrost regions, many of which are relicts of a once–widely distributed network of thaw lakes formed after the last ice age (fig. 3.3c). In fact, roughly a quarter of the Earth’s lakes lie in permafrost regions.16

The active layer grows quite soggy in summer because permafrost presents an impermeable barrier to drainage. Seasonal wetlands thrive thanks to the ample supply of near-surface liquid water. As rising ground temperatures deepen the active layer, the ground compacts and settles. Small, thawed depressions form within low-centered polygons or coalesced troughs in melting ice-wedge networks and collect standing water. The lower albedo of thaw ponds and higher heat absorption in summer localize further melting and degradation of the underlying permafrost. (The albedo of water is much lower than that of most Arctic vegetation—another aspect of the albedo feedback.) Ponds enlarge as sides cave in and bottoms thaw. Growing ponds merge with adjacent lakes, forming larger water bodies. Some small lakes connect to others via short channels in beaded streams, like beads strung on a necklace; others remain isolated, without inlet or outlet streams. As ice-rich permafrost continues to thaw, water may eventually cut through to lower ground until an outlet channel forms. Slumps and earth flows frequently develop where rivers intersect permafrost. Along low-lying shorelines, pounding waves undercut and erode exposed ice wedges, lenses, and ponds, leading to shoreline retreat (fig. 3.4).

FIGURE 3.4

Clusters of variably shaped thermokarst lakes often align along a common direction. Elongated lakes may form when prevailing summer winds set up wave patterns that focus erosion toward both ends of the lake, in a direction at right angles to the wind.17 Thaw lakes eventually drain and empty due to changes in climate, overflow of excess water into drainage outlets, or intersection with streams, other lakes, or an encroaching shoreline. Drainage may occur suddenly. Mining, construction, or road traffic on sensitive tundra, particularly in the discontinuous permafrost zone, may also initiate thawing, ground subsidence, or thermokarst, and alter drainage patterns. Even though thaw lakes are geologically short-lived features, today’s warming permafrost and new land developments are rapidly transforming thermokarst features.

DEFROSTING THE PERMAFROST

Stinky Bluffs, a steel-gray, sheer ice cliff 40 meters (131 feet) high in northeastern Alaska, provides another journey back in time some 45,000 years. The frozen ice cliff is beginning to thaw, releasing large quantities of methane and carbon dioxide—two potent greenhouse gases. The ancient decaying organic matter, recently exposed to the atmosphere, smells like rotten cabbage; hence its odoriferous name. The thawing permafrost oozes mud along the sides of the cliff and at its summit. Traversing the mucky ground feels like wading in quicksand. “We are unplugging the refrigerator in the far north. Everything that is preserved there is going to start to rot,” says Philip Camill, an ecologist from Carlton College in Northfield, Minnesota.19 Stinky Bluffs is just one smelly indication of the defrosting permafrost.20

Trees, careening like drunken sailors, are another indication. They have been likened to a visual “canary in the coal mine,” portending global warming. The trees, most commonly black spruce (Picea mariana) and birch (Betula sp.) in Alaska and larch (Larix sp.) in Siberia, grow in northern subarctic boreal forests, or taiga, over discontinuous permafrost or over ice wedges that have melted beneath. Other active permafrost processes such as frost heaving, palsa formation, earth flows, or development of thermokarst also make trees slant at precarious angles. Thermokarst undermines the shallow root systems of the trees, withdrawing the necessary support to maintain trees upright. Drunken trees often ring thermokarst lakes. Landslides or earthquakes may also make trees tilt. The seemingly intoxicated trees are not newcomers to the northern forests. Permafrost reached its southernmost limit most recently during the Little Ice Age, a cold period that peaked during the fifteenth through late eighteenth centuries. It has been in retreat since the mid-ninetreenth century. However, more and more trees are tilting crazily as northern regions are thawing.

Ground temperatures in the discontinuous permafrost zone, especially in southern Alaska and interior Canada, are between −2° and 0°C (28°–32°F) and are thus particularly vulnerable to further warming. Over the past three decades, permafrost temperatures have increased by several degrees in most regions, along with air temperatures.21 The greatest permafrost warming, around 2°–3°C (36°–37°F), has occurred in the treeless tundra regions of northern Alaska and the Canadian High Arctic. Elsewhere, permafrost temperatures have climbed by more than 0.5°C (0.9°F) since 2007–2009, with consequent deepening of the active layer. The southern borders of permafrost terrain are also shifting northward. For example, the southern boundary of permafrost in northern European Russia now lies 80 kilometers (50 miles) farther north than in the mid-1970s; that of continuous permafrost is now 15–50 kilometers (9.3–31 miles) farther north.22 In Quebec, the southern boundary of the permafrost has migrated 130 kilometers (81 miles) north during the past half century. Significant permafrost degradation has occurred in other parts of Canada and Alaska as well.

Defrosting of the permafrost manifests in diverse ways. The summer thaw penetrates deeper; more permafrost melts from top and bottom; new thermokarst terrain appears; thaw lakes expand; thaw slumps, slope failures, and rock falls multiply; and southern boundaries of permafrost shift northward.23 In the Alps, rock glaciers are on the move, as warming softens the underlying permafrost. Diminishing ground stability may also generate more rockfalls. Central Asian mountain permafrost holds considerable volumes of water as ice. Meltwater from thawing mountain permafrost could compensate for losses from receding glaciers.

Curiously, disappearing lakes may be another portent of Arctic warming. Comparison of satellite images of thousands of Siberian lakes between the 1970s and 2004 reveals a widespread drop in the number of lakes, particularly in the southern, discontinuous permafrost regions.24 More connections develop between surface and subsurface water in thinning permafrost, which allows greater infiltration to the water table and more efficient subsurface drainage. Conversely, the number of lakes in continuous permafrost has increased or expanded as hollows have filled with water and more ground has slumped.

Can permafrost, contrary to expectations, resist the coming thaw? Complex feedbacks cloud our ability to forecast the fate of permafrost. For example, more moss grows on the surface over a wider active layer. Moss is an excellent insulator that protects remaining frozen soil from rising surface temperatures. It also cools the air in the warm season by evaporation. A thick snow cover, also a superior insulator, shields the soil from further cooling in winter. However, as the snow cover thins (chap. 1), this protection weakens. In another feedback, water draining downward from the active-layer pools above the impermeable permafrost layer chills, impeding further deepening of the active layer.25 While these feedbacks could temporarily restrain the big thaw, increased defrosting (and eventual drying) of Arctic soils is likely to prevail in the long run. Over 40 percent of the permafrost could be lost by 2100, assuming high greenhouse gas emissions.26 At first, Arctic wetlands would prosper due to greater soil moisture from melting permafrost and more rainfall. But the growing warmth would also severely degrade permafrost and dry the landscape, leading to significant wetland losses. The losses, initially concentrated in the south, would advance northward as temperatures rise. Melting the permafrost not only modifies the Arctic landscape and hydrology, but also destabilizes the ground, alters the shape of the coastline, changes plant and animal communities, and could even impact global climate (see “Carbon Aloft” later in this chapter). The changes sweeping across the Arctic are just one manifestation of a larger-scale transformation extending far beyond the Arctic, as the next series of chapters will show.

PERILOUS PERMAFROST

Question: Is permafrost good?

Answer: It is not so much that permafrost is good, as losing it is bad.

Building on Unsteady Ground

Trees are not the only things that tilt at crazy angles as the ground gives way underfoot. Buildings and roads often develop large cracks that are the first warning signs of an impending collapse. Heat leaked from buildings or absorbed by road asphalt thaws underlying permafrost, leading to ground settlement that buckles the structures. Heat from these man-made structures alters the normal flow of heat into and out of the ground. Uneven thawing, such as by heat from boilers or from construction over ice wedges or atop pingos, has therefore created problems. These examples tell why Arctic construction requires special techniques to cope with permafrost.

“The best approach to building on permafrost is to avoid it.”27 But if avoidance is not an option, basic principles involve keeping the permafrost solid in order to maintain rigidity and strength.28 A building should be located on bedrock or on “thaw-stable” permafrost, such as gravels, which remain strong even when thawed. Other strategies include providing insulation and ventilation, for example, by placing a well-compacted gravel pad a few meters thick over the frozen ground and raising the structure above the pad. This provides a cold air space for heat to dissipate from the overlying structure, ventilating the space and leaving the soil frozen. Alternatively, a smaller building can be raised on concrete blocks. Insulating the structure prevents excess heat from reaching the ground. Pilings of wood, concrete, or steel driven into bedrock or a solid, stable ground layer also offer a secure building foundation. Arctic towns often employ utilidors to carry utilities such as water or sewage.

Road construction employs variants of these principles, such as leaving a layer of insulation between road and ground or, in extreme cases, digging out the permafrost (a solution practical only for fairly short segments). Another method involves using a porous rock matrix (as in an air-cooled embankment) to enable cold air to enter pores and cool the ground in winter, while trapping colder air in summer.

Construction of the Trans-Alaska oil pipeline between 1975 and 1977 required elevating much of the pipeline over continuous permafrost. The metal pipes were well insulated to prevent them from becoming brittle in the extreme cold of winter, in spite of the hot oil flowing inside. To allow caribou crossings, segments of the raised pipeline were buried. Chilled brine refrigerated adjacent ground, to dissipate heat generated by the pipeline. The pipeline in these segments was placed in gravel-covered, Styrofoam-lined trenches for insulation. Special engineering designs enabled the pipeline to cross the active Denali earthquake zone safely.29

Much of the high-altitude Tibetan Plateau also lies on permafrost. Chinese engineers building the Qinghai-Xizang railway between China and Lhasa, Tibet (completed in 2007), used crushed-rock embankments to insulate the ground and elevated the train tracks like bridges in the most fragile areas to keep them off the permafrost. As with the Trans-Alaska oil pipeline, portions of the track are cooled with ammonia-based heat exchangers.

The changing climate in the far north can impair the stability of existing buildings and new construction. Regions most sensitive to future warming lie within permafrost that is already close to thawing. Both existing and new structures will likely need to be retrofitted to survive in the transformed Arctic environment. Problems affecting infrastructure in coastal areas impacted by both melting permafrost and rising seas will require special, creative engineering solutions.

Arctic permafrost is at the mercy of sea ice.

—Barnhart et al. (2014)

More than 70 percent of the world’s beaches are eroding, according to Australian geomorphologist Eric Bird.30 He lists as many as 21 processes, both natural and anthropogenic, that nibble away at the shoreline. These include sea level rise; increased storminess and higher waves; cliffs undercut by waves; lack of sediments from cliffs, dunes, or sea floor, as well as sediments trapped behind artificial reservoirs; engineering structures that block the littoral flow of sand; and beach “mining” (excessive excavation of beach sand or gravel). Because of these myriad interacting processes, most worldwide coastal erosion cannot be blamed directly on sea level rise or climate change. Nevertheless, Arctic coastlines are crumbling—victims of the great thaw: regional warming, loss of sea ice (chap. 2), and rising seas.

Arctic coasts are especially erosion prone because permafrost-bonded sediments occupy over 65 percent of the shoreline.31 These sediments that now line the coast were deposited during the multiple ice ages of the late Quaternary Period over the last 800,000 years, at times of much lower sea level than present. Coastal permafrost possesses the mechanical strength of hard rock, but upon thawing acquires the consistency of mushy mire—easily suspended and carried away by waves—just as inland, fine-silt–sized coastal permafrost soils cemented by a high percentage of ice are the most vulnerable to ground subsidence upon thawing.32

A number of processes help drive up Arctic coastal erosion rates. These include higher Arctic Ocean summer sea surface temperatures, a longer open-water season, less summer sea ice, and generally increasing wave heights superimposed on rising sea level.33 Regional warming quickens the spring thaw and delays fall sea ice freeze-up, prolonging the open-water season. Lack of protective sea ice gives the more frequent, stronger fall storms and higher waves greater erosional opportunities. Coastal permafrost also suffers “thermal abrasion”—the impact of thaw combined with mechanical wave action—when exposed to warmer seawater. Thus, Arctic coastal cliffs and bluffs suffer a dual-front assault by air and sea.

With sea ice thin or absent, waves cut notches into the base of icy bluffs, breaking off large, ice-rich blocks that rapidly disintegrate upon falling into shallow water (fig. 3.4). Erosion increases when the sea intersects drained thermokarst (thaw lakes), ice-rich soil in ground ice, or exposed ice wedges along coastal cliffs. Keels of ice floes that gouge shallow grooves or “bulldoze” into deeper seafloor sediments also amplify erosion.34 On the other hand, mounds or ridges of sand and gravel left on the beach by melted piles of rafted ice slabs temporarily protect the shore from erosion. Because of the complex relationships that exist among the various causes of Arctic coastal erosion, their relative importance varies from place to place.

On average, Arctic coasts recede by 0.5 meters (20 inches) per year, with large regional variations.35 The Alaskan and Canadian Beaufort Sea coasts, as well as the East Siberian Arctic, experience rates greater than 2 meters per year. Alaska endures among the highest erosion rates in the world.36 For example, along a 60-kilometer (37-mile) stretch of the Alaskan Beaufort Sea, erosion rates increased from 6.8 meters (22.3 feet) per year between 1955 and 1979 to 8.7 meters (28.5 feet) annually between 1979 and 2002, and up to 13.6 meters (44.6 feet) annually between 2002 and 2007.37 A larger percentage of the coastline overall also eroded over this period. Crumbling Arctic shores not only alter the geography, but also exact a toll on those whose livelihoods depend on the land-sea interface. One such community is Shishmaref, Alaska.

Relentlessly pounding waves that undermine the shoreline could soon wash the Iñupiaq Eskimo village of Shishmaref, Alaska, into the Chukchi Sea.38 Decreasing sea ice cover and protracted wave damage magnify historic beach erosion on an open coastline with a high tidal range. The sea has already claimed a number of homes. Thawing permafrost also undermines village building foundations. Attempts to strengthen or build new seawalls have proven unsuccessful thus far. The 600 villagers, traditional hunters and fishers, seriously consider relocating to a safer spot on the nearby mainland, but face prohibitive moving costs and lack of suitable nearby land. The low elevation precludes moving houses to “safer” parts of the island. Relocation to larger towns such as Nome, Kotzebue, or Anchorage may threaten loss of community or cultural identity. Several dozen other coastal native Alaskan villages share Shishmaref’s dilemma.

A significant store of Arctic permafrost lies underwater. Submerged permafrost in relatively warmer seawater can degrade from above and also below due to the heat from the Earth’s interior. (The geothermal gradient determines the depth to the base of subsea permafrost, as on land.) Destabilization of underwater permafrost could release significant quantities of methane, in addition to that liberated by land-based boreal wetlands. The next section investigates claims of a ticking Arctic methane time bomb.

CARBON ALOFT

Northern soils hold a massive store of organic carbon—an estimated 1,700 billion metric tons—formed by remains of plants and animals that have accumulated over millennia.39 Of this store, around 1,030 billion tons lie within the top 3 meters (10 feet), with the remainder buried at depth. Microbial activity quickly degrades the freshly defrosted, carbon-rich soil, releasing methane, CH4, and carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere. These newly released greenhouse gases could reinforce the ongoing warming trend and thereby magnify the big thaw.

Researchers have long speculated that warming could unleash vast stores of the greenhouse gas [methane] from where it lies frozen beneath the sea floor and locked up in Arctic soils. If those deposits were to melt, it would almost certainly trigger abrupt climate change.

—Amanda Leigh Mascarelli (2009)

Will thawing permafrost awaken a “sleeping giant,”40 release an “economic time bomb,”41 and pose a “methane apocalypse,” as some worried researchers have asserted?42 Or instead, will it fizz gently? Methane bubbling from thaw lakes, melting permafrost, and offshore continental shelves in the Arctic is entering the atmosphere at higher rates than previously estimated.43 Methane also migrates through permeable sedimentary strata and reaches the surface along rock fissures and faults, unless confined beneath impermeable strata or favorable geologic structures. Until thawed, the impermeable permafrost cover in the Arctic generally traps and pools migrating natural gas. However, numerous new gas seeps have been discovered in Alaska and Greenland escaping along the boundaries of recently retreating glaciers and deeply buried sedimentary basins, adding to the methane bubbling out of thawing thermokarst lakes.44

Arctic permafrost soils, especially the type known as yedoma, hold 2 to 5 percent carbon by weight. Following the end of the last ice age, microbes at the bottom of oxygen-deficient thaw lakes left by retreating ice sheets generated methane as they decomposed organic matter in yedoma.45 The thawing lakes expanded, drained, accumulated sediments, and sequestered carbon in organic matter, such that by the late Holocene around 5,000 years ago, the region had transformed from a source of atmospheric carbon into a sink.46 Will this carbon sink revert back to a carbon source once again as regional warming continues? Do recent reports of rising methane emissions from land and sea (see the following paragraphs) signal the onset of a significant greenhouse gas feedback? How much of the carbon gases will be released, which ones, and how fast?

Northern wetlands and lakes constitute a potentially major methane source. But future greenhouse gas emissions will depend on whether wetlands and lakes will expand or shrink as the Arctic heats up. Satellite images show declining numbers and extent of Siberian lakes from the 1970s to the late 1990s, because of thawing permafrost. While the lakes expanded in the zone of continuous permafrost, they declined sharply in regions of discontinuous or patchy permafrost farther south, where soils had drained or dried out.47 What of the future? Wetlands abound in permafrost terrain because of poor drainage. A warming climate could initially augment wetland abundance because of increased thawing, moister soils, and greater rainfall.48 Whereas such conditions deepen the active layer, they also improve drainage to underlying soil layers, which in turn dries out the surface. Thus, an initial expansion of wetlands would eventually give way to a degraded and reduced permafrost cover. The decomposing permafrost releases methane and carbon dioxide, initiating a positive greenhouse gas feedback.

Will Arctic ecosystems dry out or grow wetter? What becomes of the carbon released from thawing permafrost? Which of the two greenhouse gases will dominate? How much additional warming will the permafrost-carbon feedback cause? Many processes compete and send contradictory messages. Streams carry some carbon from thawed permafrost to the sea, where it is buried in sediments before it can transform into greenhouse gases. To complicate matters further, extensive coastal erosion along the East Siberian Arctic Shelf relinquishes old carbon from coastal-cliff sediments.49 Two-thirds of this carbon could escape into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, while the rest is reburied in shelf sediments.

Land-based thermokarst-sensitive landscapes concentrate soil organic carbon.50 Thermokarst terrain is likely to expand, not only due to warming, but also because of more frequent wildfires and increased human development. Areas most vulnerable to sudden thaw are clustered along Arctic Ocean coastal regions and in the tundra thermokarst terrains of Eurasia. Expansion of thaw lakes has increased CH4 and CO2 emissions during the last 60 years.51 The extent to which microbes act on thawing permafrost and release methane and/or carbon dioxide may depend on soil moisture content, among other factors. In lab experiments simulating waterlogged soils, such as in peat bogs or wetlands, carbon emissions remain low, whereas well-drained soils release more carbon.52 The added moisture from thawing permafrost also spurs vegetation growth that could consume carbon emissions, but simultaneously activates methane-generating microbes. Thus, soil moisture, as well as temperature, exerts a strong control over permafrost carbon emissions.

A heated debate also swirls around the relative importance of methane versus carbon dioxide. Microbes from well-oxygenated soils (generally, drier uplands) generate mostly CO2, whereas in anaerobic (oxygen-poor) soils, such as in wetlands or peat bogs, they release a mix of both CH4 and CO2. Furthermore, aerobic (well-oxygenated) soils produce higher carbon emissions overall compared to anaerobic soils. Samples from around the world show CO2 as the dominant gas released by weight, regardless of soil environment.53 A panel of experts therefore concludes that by 2100, between 5 and 15 percent of permafrost carbon is likely to be released into the atmosphere, largely as carbon dioxide.54 However, further experiments indicate that wet, poorly oxygenated soils can generate a higher proportion of CH4 relative to CO2 than do drier, oxygenated soils.55 Inasmuch as CH4 has a much higher global warming potential than does CO2, even a small CH4 increase could thus affect climate disproportionately. On the other hand, Xiang Gao of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge and colleagues strongly discount the climate impact of permafrost-derived methane, which they estimate would raise temperatures by a mere 0.1°C (0.2°F) by century’s end.56 Even a 25-fold emissions increase would raise temperature by just 0.2°C, and a more unrealistically high 100-fold increase by only 0.8°C.

Regardless of which greenhouse gas dominates, the permafrost-carbon feedback would likely intensify the Arctic thaw. But questions still remain. For example, to what extent would plant regrowth counterbalance the permafrost-released gases? The projected prolonged growing seasons, hotter summers, added plant nutrients from decaying soils, and elevated greenhouse gas levels would all stimulate vegetation growth, which would remove some atmospheric CO2, but how much? Furthermore, how much of the added gases would microbes consume, particularly those in thawing submerged permafrost?57

In summary, the climatic effects of greenhouse gases released by thawing permafrost is a highly complex issue, depending on diverse competing processes that can operate in opposing directions. Among these are (1) the increase in atmospheric temperature, (2) the extent of future thermokarst expansion, (3) the moisture content of the soil, (4) the soil oxidation state, and (5) the proportion of CO2 to CH4 emitted, to name the main ones.

Is another kind of carbon menace lurking offshore beneath the Arctic Ocean? Offshore marine sediments around the Arctic Ocean harbor another vast storehouse of buried carbon, the fate of which is also in question, as discussed in the following section.

The 120-meter rise in sea level after the last ice age drowned an immense reservoir of organic matter trapped in permafrost. Arctic shelf seawater is typically at least −2°C (28.4°F), as compared to permafrost temperatures as low as −17°C (1.4°F).58 This marked temperature contrast potentially exposes submerged permafrost to higher future ocean temperatures. This has raised fears that recent warming Arctic Ocean water could destabilize vast quantities of methane locked in marine sediments. Are plumes of methane spewing out of the ocean a sign of recent Arctic warming or relicts from the deglacial marine incursion? The concluding section of this chapter examines the large hidden store of underwater methane in an unusual form of ice.

The Ice That Burns

Gas hydrates (also known as clathrates) are a form of ice with an open, cage-like crystal structure that can enclose gases such as methane, carbon dioxide, or hydrogen sulfide. Methane hydrate is the most common example in nature, with an approximate formula of 8CH4·46H2O (fig. 3.5a). This form of ice exists only under pressure at very low temperatures (fig. 3.5b). When methane hydrate decomposes, methane gas expands some 160 times by volume. Enormous quantities of methane hydrates are believed to be buried in Arctic permafrost and in marine sediments on the continental slope and rise (conservatively estimated at 1,800 billion metric tons globally59).

FIGURE 3.5

In the Arctic, the marine hydrate stability zone ranges from depths of at least 300 meters to more than 1,000 meters (980–3280 feet) on continental shelf and slope sediments, and several hundred meters deep within and below land permafrost. The thickness of the marine hydrate stability zone is determined by the temperature and seafloor depth and the intersection of the methane hydrate stability curve with the geothermal gradient in ocean sediment. On land, the thickness depends on the intersection of the hydrate stability curve with the geothermal gradient in both permafrost and sediment (fig. 3.5b). Methane hydrate dissociates violently into methane and water when either temperatures rise or pressures are relieved by lowered sea level. The base of the hydrate stability zone defines an impenetrable surface that traps any free methane gas escaping from depth.60 The gas hydrate layer may begin to decompose after a slight increase in shallow bottom-water temperatures or a sea level drop. If enough free gas accumulates beneath the marine hydrate stability zone on the continental slope, pressures could exceed that of overlying sediment or water. A slight perturbation could then potentially trigger a catastrophic slope failure. Like uncorking a champagne bottle, the sudden decrease in confining pressure would cause slumping of the destabilized hydrate layer, triggering submarine landslides, or even tsunamis.61 In a snowballing effect, underlying gas-rich sediments would also be entrained into the growing landslide (fig. 3.6).

FIGURE 3.6

Submarine landslides triggered by decomposing hydrates in marine sediments. The liberated methane gas quickly travels to the ocean surface and atmosphere, where it rapidly oxidizes to carbon dioxide. (G. R. Dickens and C. Forswall, “Methane Hydrates, Carbon Cycling, and Environmental Change,” in Encyclopedia of Paleoclimatology and Ancient Environments, ed. V. Gornitz [Dordrecht: Springer, 2009], 563. Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature)

Alternatively, earthquakes could shake loose unstable overlying marine sediments, also generating massive underwater avalanches that would rupture hydrate-bearing strata and release any confined methane gas. However, marine landslides also occur in the absence of past or present gas hydrates. Other processes, such as weak, unconsolidated sediment horizons or high fluid pore pressures in rapidly deposited sediment, also induce slope instability and eventual collapse. No conclusive evidence links the timing of major submarine landslide events to large-scale methane releases or to climate change.62

Methane gas is bubbling up from more than 250 active plumes on the seabed at depths of 150 to 400 meters (490–1,300 feet) along the West Spitsbergen continental margin, the East Siberian Arctic Shelf (a drowned extension of Siberian tundra), and elsewhere in the Arctic Ocean.63 The East Siberian Arctic Shelf alone is emitting an estimated 17 million tons of methane gas per year. However, most of this methane may not even reach the atmosphere. Some dissolves in seawater; microbes also quickly convert it into biomass and carbon dioxide. Are observed methane emissions even caused by the recent ocean warming, or are they simply ongoing processes dating back thousands of years? Not all marine methane may derive from decomposing gas hydrates; instead they may derive from now-thawing, drowned, carbon-rich permafrost; from eroding shore cliffs; or from gas escaping from deep-seated ocean reservoirs. Microbes living in oxygen-deficient seawater feed on methane in the presence of dissolved sulfate, quickly oxidizing it to carbon dioxide.64 Stores of subsea hydrates may have also been overestimated, and much of what exists may be buried deep enough to remain undisturbed by ocean warming for centuries to come.65 Can the escaping methane therefore awaken a sleeping giant?

As Anil Ananthaswamy, a reporter for the New Scientist, assures us: “The one thing we don’t need to worry about is the so-called methane time bomb…. An imminent release massive enough to accelerate warming can be ruled out.”66 Continued climate warming over the next century or two is less likely to unleash an explosive time bomb than to create a gentle fizz like that from an opened can of soda. Nevertheless, hydrate deposits on the shallow continental shelves and slopes surrounding the Arctic Ocean will remain vulnerable to dissociation under ongoing and future warming. Although their present-day contribution is still fairly small, methane and carbon dioxide emissions from both thawing land permafrost and Arctic Ocean continental shelf/slope sediments will likely augment the growing anthropogenic greenhouse gas burden.

As this and the previous chapters have shown, climate change is already under way throughout most of the Arctic, faster there than elsewhere on the planet. Losses of permafrost and floating ice will amplify climate change in the Arctic, creating distant ripple effects. However, the real bull in the china shop is the ultimate fate of glaciers and ice sheets and their roles in sea level rise and in water resources. These impacts could ultimately affect hundreds of millions of people worldwide. A closer look into these processes guides the remaining chapters of this book.