10

An Ordered Probit Analysis

of Transaction Stock Prices

10.1 Introduction

VIRTUALLY ALL EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATIONS of the microstructure of securities markets require a statistical model of asset prices that can capture the salient features of price movements from one transaction to the next. For example, because there are several theories of why bid/ask spreads exist, a stochastic model for prices is a prerequisite to empirically decomposing observed spreads into components due to order-processing costs, adverse selection, and specialist market power.1 The benefits and costs of particular aspects of a market's microstructure, such as margin requirements, the degree of competition faced by dealers, the frequency that orders are cleared, and intraday volatility also depend intimately on the particular specification of price dynamics.2 Even the event study, a tool that does not explicitly assume any particular theory of the market microstructure, depends heavily on price dynamics (see, for example, Barclay and Litzenberger (1988)). In fact, it is difficult to imagine an economically relevant feature of transaction prices and the market microstructure that does not hinge on such price dynamics.

Since stock prices are perhaps the most closely watched economic variables to date, they have been modeled by many competing specifications, beginning with the simple random walk or Brownian motion. However, the majority of these specifications have been unable to capture at least three aspects of transaction prices. First, on most U.S. stock exchanges, prices are quoted in increments of eighths of a dollar, a feature not captured by stochastic processes with continuous state spaces. Of course, discreteness is less problematic for coarser-sampled data, which may be well-approximated by a continuousstate process. But discreteness is of paramount importance for intraday price movements, since such finely-sampled price changes may take on only five or six distinct values3.

The second distinguishing feature of transaction prices is their timing, which is irregular and random. Therefore, such prices may be modeled by discrete-time processes only if we are prepared to ignore the information contained in waiting times between trades.

Finally, although many studies have computed correlations between transaction price changes and other economic variables, to date none of the existing models of discrete transaction prices have been able to quantify such effects formally. Such models have focused primarily on the unconditional distribution of price changes, whereas what is more often of economic interest is the conditional distribution, conditioned on quantities such as volume, time between trades, and the sequence of past price changes.4 For example, one of the unresolved empirical issues in this literature is what the total costs of immediate execution are, which many take to be a measure of market liquidity. Indeed, the largest component of these costs may be the price impact of large trades. A floor broker seeking to unload 100,000 shares of stock will generally break up the sale into smaller blocks to minimize the price impact of the trades. How do we measure price impact? Such a question is a question about the conditional distribution of price changes, conditional upon a particular sequence of volume and price changes, i.e., order flow.

In this chapter, we propose a specification of transaction price changes that addresses all three of these issues, and yet is still tractable enough to permit estimation via standard techniques. This specification is known as ordered probit, a technique used most frequently in cross-sectional studies of dependent variables that take on only a finite number of values possessing a natural ordering.5 For example, the dependent variable might be the level of education, as measured by three categories: less than high school, high school, and college education. The dependent variable is discrete, and is naturally ordered since college education always follows high school (see Maddala (1983) for further details). Heuristically, ordered probit analysis is a generalization of the linear regression model to cases where the dependent variable is discrete. As such, among the existing models of stock price discreteness (e.g., Ball (1988), Cho and Frees (1988), Gottlieb and Kalay (1985), and Harris (1991)), ordered probit is perhaps the only specification that can easily capture the impact of “explanatory” variables on price changes while also accounting for price discreteness and irregular trade times.

Underlying the analysis is a “virtual” regression model with an unobserved continuous dependent variable Z* whose conditional mean is a linear function of observed “explanatory” variables. Although Z* is unobserved, it is related to an observable discrete random variable Z, whose realizations are determined by where Z* lies in its domain or state space. By partitioning the state space into a finite number of distinct regions, Z may be viewed as an indicator function for Z* over these regions. For example, a discrete random variable Z taking on the values {- ,0,

,0, } may be modeled as an indicator variable that takes on the value -

} may be modeled as an indicator variable that takes on the value - whenever Z* ≤ α1,the value 0 whenever α1 < Z* ≤ α2, and the value

whenever Z* ≤ α1,the value 0 whenever α1 < Z* ≤ α2, and the value  whenever Z*>α2. Ordered probit analysis consists of estimating α1,α2 and the coefficients of the unobserved regression model that determines the conditional mean and variance of Z*.

whenever Z*>α2. Ordered probit analysis consists of estimating α1,α2 and the coefficients of the unobserved regression model that determines the conditional mean and variance of Z*.

Since α1,α2, and Z* may depend on a vector of “regressors” X, ordered probit analysis is considerably more general than its simple structure suggests. In fact, it is well-known that ordered probit can fit any arbitrary multinomial distribution. However, because of the underlying linear regression framework, ordered probit can also capture the price effects of many economic variables in a way that models of the unconditional distribution of price changes cannot.

To motivate our methodology and to focus it on specific market microstructure applications, we consider three questions concerning the behavior of transaction prices. First, how does the particular sequence of trades affect the conditional distribution of price changes, and how do these effects differ across stocks? For example, does a sequence of three consecutive buyer-initiated trades (“buys”) generate price pressure, so that the next price change is more likely to be positive than if the sequence were three consecutive seller-initiated trades (“sells”), and how does this pressure change from stock to stock? Second, does trade size affect price changes as some theories suggest, and if so, what is the price impact per unit volume of trade from one transaction to the next? Third, does price discreteness matter? In particular, can the conditional distribution of price changes be modeled as a simple linear regression of price changes on explanatory variables without accounting for discreteness at all? Within the context of the ordered probit framework, we shall obtain sharp answers to each of these questions.

In Section 10.2, we review the ordered probit model and describe its estimation via maximum likelihood. We describe the data in Section 10.3 by presenting detailed summary statistics for an initial sample of six stocks. In Section 10.4, we discuss the empirical specification of the ordered probit model and the selection of conditioning or “explanatory” variables. The maximum likelihood estimates for our initial sample are reported in Section 10.5, along with some diagnostic specification tests. In Section 10.6, we use these maximum likelihood estimates in three specific applications: (1) testing for order-flow dependence, (2) measuring price impact, and (3) comparing ordered probit to simple linear regression. And as a check on the robustness of our findings, in Section 10.7 we present less detailed results for a larger and randomly chosen sample of 100 stocks. We conclude in Section 10.8.

10.2 The Ordered Probit Model

Consider a sequence of transaction prices P(to), P(t1), …, P(tn) observed at times t1 t2 t3.…,tn, and denote by Z1, Z2,…, Zn the corresponding price changes, where Zk ≡ P(tk)-P(tk-1) is assumed to be an integer multiple of some divisor called a “tick” (such as an eighth of a dollar). Let Z*k denote an unobservable continuous random variable such that

where “i.n.i.d.” indicates that the  ’s are independently but not identically distributed, and X k is a q × 1 vector of predetermined variables that governs the conditional mean of Z*k. Note that subscripts are used to denote “transaction” time, whereas time arguments tk denote calendar or “clock” time, a convention we shall follow throughout the chapter.

’s are independently but not identically distributed, and X k is a q × 1 vector of predetermined variables that governs the conditional mean of Z*k. Note that subscripts are used to denote “transaction” time, whereas time arguments tk denote calendar or “clock” time, a convention we shall follow throughout the chapter.

The essence of the ordered probit model is the assumption that observed price changes Zk are related to the continuous variable Z*k in the following manner:

where the sets Aj form apartition of the state spaceS* of Z*k, i.e., S* =Umj=l and Ai ∩ Aj= for i ≠ j, and the sj’s are the discrete values that comprise the state space S of Z*k.

for i ≠ j, and the sj’s are the discrete values that comprise the state space S of Z*k.

The motivation for the ordered probit specification is to uncover the mapping between S* and S and relate it to a set of economic variables or “regressors.” In our current application, the sj’s are 0, and so on, and for simplicity we define the state-space partition of S* to be intervals:

and so on, and for simplicity we define the state-space partition of S* to be intervals:

Although the observed price change can be any number of ticks, positive or negative, we assume that m in (10.2.2) is finite to keep the number of unknown parameters finite. This poses no problems, since we may always let some states in S represent a multiple (and possibly countably infinite) number of values for the observed price change. For example, in our empirical application we define s1 to be a price change of -4 ticks or less, s9 to be a price change of +4 ticks or more, and s2 to s8 to be price changes of -3 ticks to +3 ticks respectively. This parsimony is obtained at the cost of losing price resolution—under this specification the ordered probit model does not distinguish between price changes of +4 and price changes greater than +4 (since the +4tick outcome and the greater than +4tick outcome have been grouped together into a common event), and similarly for price changes of -4 ticks versus price changes less than -4. Of course, in principle the resolution may be made arbitrarily finer by simply introducing more states, i.e., by increasing m. Moreover, as long as (10.2.1) is correctly specified, then increasing price resolution will not affect the estimated β’s asymptotically (although finite sample properties may differ). However, in practice the data will impose a limit on the fineness of price resolution simply because there will be no observations in the extreme states when m is too large, in which case a subset of the parameters is not identified and cannot be estimated.

Observe that the  ’s in (10.2.1) are assumed to be conditionally independently but not identically distributed, conditioned on the Xk's and other economic variables Wk influencing the conditional variance

’s in (10.2.1) are assumed to be conditionally independently but not identically distributed, conditioned on the Xk's and other economic variables Wk influencing the conditional variance  6 This allows for clock-time effects, as in the case of an arithmetic Brownian motion where the variance

6 This allows for clock-time effects, as in the case of an arithmetic Brownian motion where the variance  of price changes is linear in the time between trades. We also allow for more general forms of conditional heteroskedasticity by letting

of price changes is linear in the time between trades. We also allow for more general forms of conditional heteroskedasticity by letting  depend linearly on other economic variables Wk, which differs from Engle's (1982) ARCH process only in its application to a discrete dependent variable model requiring an additional identification assumption that we shall discuss below in Section 10.4.

depend linearly on other economic variables Wk, which differs from Engle's (1982) ARCH process only in its application to a discrete dependent variable model requiring an additional identification assumption that we shall discuss below in Section 10.4.

The dependence structure of the observed process Zk is clearly induced by that of Z*k and the definitions of the Aj's, since

As a consequence, if the variables Xk and Wk are temporally independent, the observed process Zk is also temporally independent. Of course, these are fairly restrictive assumptions and are certainly not necessary for any of the statistical inferences that follow. We require only that the  's be conditionally independent, so that all serial dependence is captured by the Xk's and the Wk's. Consequently, the independence of the

's be conditionally independent, so that all serial dependence is captured by the Xk's and the Wk's. Consequently, the independence of the  's does not imply that the Z*k’s are independently distributed because we have placed no restrictions on the temporal dependence of the Xk's or Wk' s.

's does not imply that the Z*k’s are independently distributed because we have placed no restrictions on the temporal dependence of the Xk's or Wk' s.

The conditional distribution of observed price changes Z*k, conditioned on Xk and Wk, is determined by the partition boundaries and the particular distribution of  For Gaussian

For Gaussian  's, the conditional distribution is

's, the conditional distribution is

where Φ(•) is the standard normal cumulative distribution function.

To develop some intuition for the ordered probit model, observe that the probability of any particular observed price change is determined by where the conditional mean lies relative to the partition boundaries. Therefore, for a given conditional mean X'kß, shifting the boundaries will alter the probabilities of observing each state (see Figure 10.1). In fact, by shifting the boundaries appropriately, ordered probit can fit any arbitrary multinomial distribution. This implies that the assumption of normality underlying ordered probit plays no special role in determining the probabilities of states; a logistic distribution, for example, could have served equally well.

Figure 10.1. Illustration of ordered probit pro babilities pi of observing a price change of Si ticks, which are determined by where the unobservable “virtual” price change Z*k falls. In particular, if Z*k falls in the interval (αi-1,αi] then the ordered probit model implies that the observed price change Zk is si ticks. More formally, pi ≡ Prob(Z*k = si | Xk, Wk) = Prob(αi-1≤αi | Xk, Wk), i = 1,…, 9, where, for notational simplicity, we define α0=-∞ and α9≡+∞. The ordered probit model captures the effect of economic variables Xk, Wk on the virtual price change and places enough structure on the probabilities pi to permit their estimation by maximum likelihood.

However, since it is considerably more difficult to capture conditional heteroskedasticity in the ordered logit model, we have chosen the Gaussian specification.

Given the partition boundaries, a higher conditional mean X'kß implies a higher probability of observing a more extreme positive state. Of course, the labeling of states is arbitrary, but the ordered probit model makes use of the natural ordering of the states. The regressors allow us to separate the effects of various economic factors that influence the likelihood of one state versus another. For example, suppose that a large positive value of X1 usually implies a large negative observed price change and vice versa. Then the ordered probit coefficient ß1 will be negative in sign and large in magnitude (relative to σk of course).

By allowing the data to determine the partition boundaries α, the coefficients ß of the conditional mean, and the conditional variance σk2, the ordered probit model captures the empirical relation between the unobservable continuous state space S* and the observed discrete state space S as a function of the economic variables Xk and Wk

10.2.1 Other Models of Discreteness

From these observations, it is apparent that the rounding/eighths-barriers models of discreteness in Ball (1988), Cho and Frees (1988), Gottlieb and Kalay (1985) and Harris (1991) may be reparametrized as ordered probit models. Consider first the case of a “true” price process that is an arithmetic Brownian motion, with trades occurring only when this continuous-state process crosses an eighths threshold (see Cho and Frees (1988)). Observed trades from such a process may be generated by an ordered probit model in which the partition boundaries are fixed at multiples of eighths and the single regressor is the time interval (or first-passage time) between crossings, appearing in both the conditional mean and variance of Z*k.

To obtain the rounding models of Ball (1988), Gottlieb and Kalay (1985), and Harris (1991), which do not make use of waiting times between trades, define the partition boundaries as the midpoint between eighths, e.g., the observed price change is  if the virtual price process lies in the interval

if the virtual price process lies in the interval  and omit the waiting time as a regressor in both the conditional mean and variance (see the discussion in Section 10.6.3 below).

and omit the waiting time as a regressor in both the conditional mean and variance (see the discussion in Section 10.6.3 below).

The generality of the ordered probit model comes from the fact that the rounding and eighths-barrier models of discreteness are both special cases of ordered probit under appropriate restrictions on the partition boundaries. In fact, since the boundaries may be parametrized to be time- and statedependent, ordered probit can allow for considerably more general kinds of rounding and eighths barriers. In addition to fitting any arbitrary multinomial distribution, ordered probit may also accommodate finite-state Markov chains and compound Poisson processes.

Of course, other models of discreteness are not necessarily obsolete, since in several cases the parameters of interest may not be simple functions of the ordered probit parameters. For example, a tedious calculation will show that although Harris's (1991) rounding model may be represented as an ordered probit model, the bid/ask spread parameter c is not easily recoverable from the ordered probit parameters. In such cases, other equivalent specifications may allow more direct estimation of the parameters of interest.

10.2.2 The Likelihood Function

Let Yik be an indicator variable which takes on the value one if the realization of the kth observation Zk is the ith state si, and zero otherwise. Then the log-likelihood function  for the vector of price changes Z=[Z1 Z2…Zn]', conditional on the explanatory variables X = [X1 X2…Xn]', is given by

for the vector of price changes Z=[Z1 Z2…Zn]', conditional on the explanatory variables X = [X1 X2…Xn]', is given by

Recall that  is a conditional variance, conditioned upon Xk. This allows for conditional heteroskedasticity in the Z*k's, as in the rounding model of Cho and Frees (1988) where the Z*k's are increments of arithmetic Brownian motion with variance proportional to tk – tk-1. In fact, arithmetic Brownian motion may be accommodated explicitly by the specification

is a conditional variance, conditioned upon Xk. This allows for conditional heteroskedasticity in the Z*k's, as in the rounding model of Cho and Frees (1988) where the Z*k's are increments of arithmetic Brownian motion with variance proportional to tk – tk-1. In fact, arithmetic Brownian motion may be accommodated explicitly by the specification

More generally, we may also let  depend on other economic variables Wk, so that

depend on other economic variables Wk, so that

There are, however, some constraints that must be placed on these parameters to achieve identification since, for example, doubling the α's, the β's, and σk leaves the likelihood unchanged. We shall return to this issue in Section 10.4.

10.3 The Data

The Institute for the Study of Securities Markets (ISSM) transaction database consists of time-stamped trades (to the nearest second), trade size, and bid/ask quotes from the New York and American Stock Exchanges and the consolidated regional exchanges from january 4 to December 30 of 1988. Because of the sheer size of the ISSM database, most empirical studies of the market microstructure have concentrated on more manageable subsets of the database, and we also follow this practice. But because there is so much data, the “pretest” or “data-snooping” biases associated with any nonrandom selection procedure used to obtain the smaller subsets are likely to be substantial. As a simple example of such a bias, suppose we choose our stocks by the seemingly innocuous requirement that they have a minimum of 100,000 trades in 1988. This rule will impart a substantial downward bias on our measures of price impact because stocks with over 100,000 trades per year are generally more liquid and, almost by definition, have smaller price impact. Therefore, how we choose our subsample of stocks may have important consequences for how our results are to be interpreted, so we shall describe our procedure in some detail here.

We first begin with an initial “test” sample containing five stocks that did not engage in any stock splits or stock dividends greater than 3 : 2 during 1988: Alcoa, Allied Signal, Boeing, DuPont, and General Motors. We restrict splits because the effects of price discreteness to be captured by our model are likely to change in important ways with dramatic shifts in the price level; by eliminating large splits we reduce the problem of large changes in the price level without screening on prices directly. (Of course, if we were interested in explaining stock splits, this procedure would obviously impart important biases in the empirical results.) We also chose these five stocks because they are relatively large and visible companies, each with a large number of trades, and therefore likely to yield accurate parameter estimates. We then performed the standard “specification searches” on these five stocks, adding, deleting, and transforming regressors to obtain a “reasonable” fit. By “reasonable” we mean primarily the convergence of the maximum likelihood estimation procedure, but it must also include Learner's (1978) kind of informal or ad hoc inferences that all empiricists engage in.

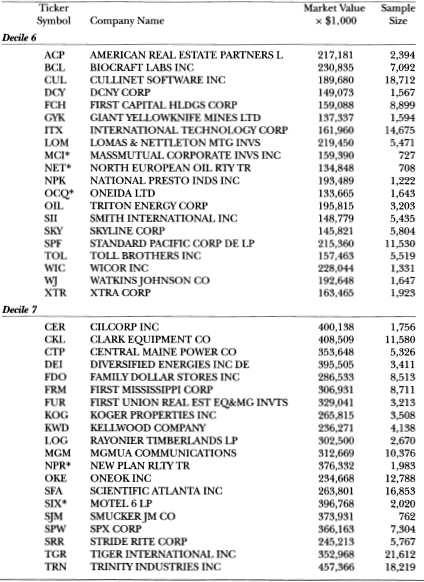

Once we obtain a specification that is “reasonable,” we estimate it without further revision for our primary sample of six new stocks, chosen to yield a representative sample with respect to industries, market value, price levels, and sample sizes. They are International Business Machines Corporation (IBM), Quantum Chemical Corporation (CUE), Foster Wheeler Corporation (FWC), Handy and Harman Company (HNH), Navistar International Corporation (NAV), and American Telephone and Telegraph Incorporated (T). (Our original primary sample consists of eleven stocks but we omitted the results for five of them to conserve space. See Hausman, Lo, and MacKinlay (1991) for the full set of results.) By using the specification derived from the test sample on stocks in this fresh sample, we seek to lessen the impact of any data-snooping biases generated by our specification searches. If, for example, our parameter estimates and subsequent inferences change dramatically in the new sample (in fact, they do not) this might be a sign that our test-sample findings were driven primarily by selection biases.

As a final check on the robustness of our specification, we estimate it for a larger sample of 100 stocks chosen randomly, and these companies are listed in Table 10.5. From this larger sample, it is apparent that our smaller six-stock sample does suffer from at least one selection bias: it is comprised of relatively well-known companies. In contrast, relatively few companies in Table 10.5 are as familiar. Despite this bias, virtually all of our empirical findings are confirmed by the larger sample. To conserve space and to focus attention on our findings, we report the complete set of summary statistics and estimation results only for the smaller sample of six stocks, and present broader and less detailed findings for the extended sample afterwards.

Of course, as long as there is cross-sectional dependence among the two samples it is impossible to eliminate such biases completely. Moreover, samples drawn from a different time period are not necessarily free from selection bias as some have suggested, due to the presence of temporal dependence. Unfortunately, nonexperimental inference is always subject to selection biases of one kind or another since specification searches are an unavoidable aspect of genuine progress in empirical research (see, for example, Lo and MacKinlay (1990b)). Even Bayesian inference, which is not as sensitive to the kinds of selection biases discussed in Leamer (1978), can be distorted in subtle ways by specification searches. Therefore, beyond our test-sample procedure, we can only alert readers to the possibility of such biases and allow them to adjust their own inferences accordingly.

10.3.1 Sample Statistics

We take as our basic time series the intraday price changes from trade to trade, and discard all overnight price changes. That the statistical properties of overnight price changes differ considerably from those of intraday price changes has been convincingly documented by several authors, most recently by Amihud and Mendelson (1987), Stoll and Whaley (1990), and Wood, McInish, and Ord (1985). Since the three market microstructure applications we are focusing on involve intraday price behavior, and overnight price changes are different enough to warrant a separate specification, we use only intraday price changes. The first and last transaction prices of each day are also discarded, since they differ systematically from other prices due to institutional features (see Amihud and Mendelson (1987) for further details).

Several other screens were imposed to eliminate “problem” trades and quotes, yielding sample sizes ranging from 3,174 trades for HNH to 206,794 trades for IBM. Specifically: (1) all trades flagged with the following ISSM condition codes were eliminated: A, C, D, O, R, and Z (see the ISSM documentation for further details concerning trade condition codes); (2) transactions exceeding 3,276,000 shares [termed “big trades” by ISSM] were also eliminated; (3) because we use three lags of price changes and three lags of five-minute returns on the S&P 500 index futures prices as explanatory variables, we do not use the first three price changes or price changes during the first 15 minutes of each day (whichever occurs later) as observations of the dependent variable; and (4) since S&P 500 futures data were not available on November 10, 11, and the first two trading hours of May 3, trades during these times were also omitted.

For some stocks, a small number of transactions occurred at prices denominated in  of a dollar (non-NYSE trades). In these cases, we rounded the price randomly (up or down) to the nearest

of a dollar (non-NYSE trades). In these cases, we rounded the price randomly (up or down) to the nearest  , and if necessary, also rounded the bid/ask quotes in the same direction.

, and if necessary, also rounded the bid/ask quotes in the same direction.

Quotes implying bid/ask spreads greater than 40 ticks or flagged with the following ISSM condition codes were also eliminated: C, D, F, G, I, L, N, P, S, V, X, and Z (essentially all “BBO-1neligible” quotes; see the ISSM documentation for further details concerning the definitions of the particular trade and quote condition codes, and Eikeboom (1992) for a thorough study of the relative frequencies of these condition codes for a small subset of the ISSM database).

Since we also use bid and ask prices in our analysis, some discussion of how we matched quotes to prices is necessary. Bid/ask quotes are reported on the ISSM tape only when they are revised, hence it is natural to match each transaction price to the most recently reported quote prior to the transaction. However, Bronfman (1991), Lee and Ready (1991), and others have shown that prices of trades that precipitate quote revisions are sometimes reported with a lag, so that the order of quote revision and transaction price is reversed in official records such as the ISSM tapes. To address this issue, we match transaction prices to quotes that are set at least five seconds prior to the transaction; the evidence in Lee and Ready (1991) suggests that this will account for most of the missequencing.

To provide some intuition for this enormous dataset, we report a few summary statistics in Table 10.1. Our sample contains considerable price dispersion, with the low stock price ranging from $3.125 for NAV to $104.250 for IBM, and the high ranging from $7.875 for NAV to $129.500 for IBM. At $219 million, HNH has the smallest market capitalization in our sample, and IBM has the largest with a market value of $69.8 billion.

For our empirical analysis we also require some indicator of whether a transaction was buyer-initiated or seller-initiated. Obviously, this is a difficult task because for every trade there is always a buyer and a seller. What we are attempting to measure is which of the two parties is more anxious to consummate the trade and is therefore willing to pay for it in the form of the bid/ask spread. Perhaps the most obvious indicator is whether the transaction occurs at the ask price or at the bid price; if it is the former then the transaction is most likely a “buy,” and if it is the latter then the transaction is most likely a “sell.” Unfortunately, a large number of transactions occur at prices strictly within the bid/ask spread, so that this method for signing trades will leave the majority of trades indeterminate.

Following Blume, MacKinlay, and Terker (1989) and many others, we classify a transaction as a buy if the transaction price is higher than the mean of the prevailing bid/ask quote (the most recent quote that is set at least five seconds prior to the trade), and classify it as a sell if the price is lower. Should the price equal the mean of the prevailing bid/ask quote, we classify the trade as an “indeterminate” trade. This method yields far fewer indeterminate trades than classifying according to transactions at the bid or at the ask.

Table 10.1. Summary statistics for transaction prices and corresponding ordered probit explanatory variables of International Business Machines Corporation (IBM-206,794 trades), Quantum Chemical Corporation (CUE - 26,927 trades), Foster Wheeler Corporation (FWC - 18,199 trades), Handy and Harman Company (HNH - 3,174 trades), Navistar International Corporation (NAV - 96,127 trades), and American Telephone and Telegraph Company (T - 180,726 trades), for the period from january 4, 1988, to December 30, 1988.

1 Computed at the beginning of the sample period.

2 Five-minute continuously compounded returns of the S&P 500 index futures price, for the contract maturing in the closest month beyond the month in which transaction k occurred, where the return corresponding to the kth transaction is computed with the futures price recorded one minute before the nearest round minute prior to tk and the price recorded five minutes before this.

3 Takes the value 1 if the kth transaction price is greater than the average of the quoted bid and ask prices at time tk, the value -1 if the kth transaction price is less than the average of the quoted bid and ask prices at time tk, and 0 otherwise.

4 Box-Cox transformation of dollar volume multiplied by the buy/sell indicator, where the Box- Cox parameter λ is estimated jointly with the other ordered probit parameters via maximum likelihood. The Box-Cox parameter λ determines the degree of curvature that the transformation Tλ(•) exhibits in transforming dollar volume Vk before inclusion as an explanatory variable in the ordered probit specification. If λ = 1, the transformation Tλ(•) is linear, hence dollar volume enters the ordered probit model linearly. If λ = 0, the transformation is equivalent to log(•), hence the natural logarithm of dollar volume enters the ordered probit model. When λ is between 0 and 1, the curvature of Tλ(•) is between logarithmic and linear.

Unfortunately, little is known about the relative merits of this method of classification versus others such as the “tick test” (which classifies a transaction as a buy, a sell, or indeterminate if its price is greater than, less than, or equal to the previous transaction's price, respectively), simply because it is virtually impossible to obtain the data necessary to evaluate these alternatives. The only study we have seen is by Robinson (1988, Chapter 4.4.1, Table 19), in which he compared the tick test rule to the bid/ask mean rule for a sample of 196 block trades initiated by two major Canadian life insurance companies, and concluded that the bid/ask mean rule was considerably more accurate.

From Table 10.1 we see that 13-26% of each stock's transactions are indeterminate, and the remaining trades fall almost equally into the two remaining categories. The one exception is the smallest stock, HNH, which has more than twice as many sells as buys.

The means and standard deviations of other variables to be used in our ordered probit analysis are also given in Table 10.1. The precise definitions of these variables will be given below in Section 10.4, but briefly, Zk is the price change between transactions k - 1 and k,  tk is the time elapsed between these trades, ABk is the bid/ask spread prevailing at transaction k, SP500k is the return on the S&P 500 index futures price over the five-minute period immediately preceding transaction k, IBSk is the buy/sell indicator described above (1 for a buy, -1 for a sell, and 0 for an indeterminate trade), and Tλ(Vk) is a transformation of the dollar volume of transaction k, transformed according to the Box and Cox (1964) specification with parameter λi which is estimated for each stock i by maximum likelihood along with the other ordered probit parameters.

tk is the time elapsed between these trades, ABk is the bid/ask spread prevailing at transaction k, SP500k is the return on the S&P 500 index futures price over the five-minute period immediately preceding transaction k, IBSk is the buy/sell indicator described above (1 for a buy, -1 for a sell, and 0 for an indeterminate trade), and Tλ(Vk) is a transformation of the dollar volume of transaction k, transformed according to the Box and Cox (1964) specification with parameter λi which is estimated for each stock i by maximum likelihood along with the other ordered probit parameters.

From Table 10.1 we see that for the larger stocks, trades tend to occur almost every minute on average. Of course, the smaller stocks trade less frequently, with HNH trading only once every 18 minutes on average. The median dollar volume per trade also varies considerably, ranging from $3,000 for relatively low-priced NAV to $57,375 for higher-priced IBM.

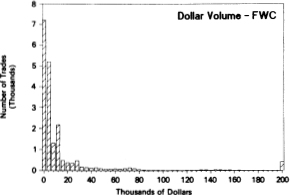

Finally, Figure 10.2 contains histograms for the price change, timebetween- trade, and dollar volume variables for the six stocks. The histograms of price changes are constructed so that the most extreme cells also include observations beyond them, i.e., the level of the histogram for the -4 tick cell reflects all price changes of -4 ticks or less, and similarly for the +4 ticks cell. Surprisingly, these price histograms are remarkably symmetric across all stocks. Also, virtually all the mass in each histogram is concentrated in five or seven cells-there are few absolute price changes of four ticks or more, which underscores the importance of discreteness in transaction prices.

Figure 10.2. Histograms of price changes, time-between-trades, and dollar volume of International Business Machines Corporation (IBM - 206,794 trades), Quantum Chemical Corporation (CUE-26,927 trades), Foster Wheeler Corporation (FWC- 18,199 trades), Handy andHarman Company (HNH - 3,174 trades), Navistar International Corporation (NAV- 96,127 trades), and American Telephone and Telegraph Company (T - 180,726 trades), for the period from fanuary 4, 1988, to December 30, 1988.

For both the time-between-trade and dollar volume variables, the largest cell, i.e., 1,500 seconds or $200,000, also includes all trades beyond it. As expected, the histograms for these quantities vary greatly according to market value and price level. For the larger stocks, the time between trades is relatively short, hence most of the mass in those histograms is in the lower- valued cells. But the histograms of smaller, less liquid stocks like HNH have spikes in the largest-valued cell. Histograms for dollar volume are sometimes bimodal, as in the case of IBM, reflecting both round-lot trading at 100 shares ($10,000 on average for IBM's stock price during 1988) and some very large trades, presumably by institutional investors.

10.4 The Empirical Specification

To estimate the parameters of the ordered probit model via maximum likelihood, we must first specify (i) the number of states m, (ii) the explanatory variables Xk and (iii) the parametrization of the variance  .

.

In choosing m, we must balance price resolution against the practical constraint that too large an m will yield no observations in the extreme states s1 and sm. For example, if we set m to 101 and define the states s1 and s101 symmetrically to be price changes of -50 ticks and +50 ticks respectively, we would find no Zk's among our six stocks falling into these two states. Using the histograms in Figure 10.2 as a guide, we set m = 9 for the larger stocks, implying extreme states of -4 ticks or less and +4 ticks or more. For the two smaller stocks, FWC and HNH, we set m = 5, implying extreme states of -2 ticks or less and +2 ticks or more. Although the definition of states need not be symmetric (state s1 can be -6 ticks or less, implying that state 59 is +2 ticks or more), the symmetry of the histogram of price changes in Figure 10.2 suggests a symmetric definition of the sj's.

In selecting the explanatory variables Xk, we seek to capture several aspects of transaction price changes. First, we would like to allow for clocktime effects, since there is currently some dispute over whether trade-totrade prices are stable in transaction time versus clock time. Second, we would like to account for the effects of the bid/ask spread on price changes, since many transactions are merely movements from the bid price to the ask price or vice versa. If, for example, in a sequence of three trades the first and third were buyer-initiated while the second was seller-initiated, the sequence of transaction prices would exhibit reversals due solely to the bid/ask “bounce.” Third, we would like to measure how the conditional distribution of price changes shifts in response to a trade of a given volume, i.e., the price impact per unit volume of trade. And fourth, we would like to capture the effects of “systematic” or market-wide movements in prices on the conditional distribution of an individual stock's price changes. To address these four issues, we first construct the following variables:

tk = Time elapsed between transactions k — 1 and k, in seconds.

tk = Time elapsed between transactions k — 1 and k, in seconds.

ABk-l = Bid/ask spread prevailing at time tk-1, in ticks.

Zk-l = Three lags [l = 1, 2, 3] of the dependent variable Z*k. Recall that for m = 9, price changes less then -4 ticks are set equal to -4 ticks (state si), and price changes greater than +4 ticks are set equal to +4 ticks (state 59), and similarly for m = 5.

Vk-1 = Three lags [l = 1, 2, 3] of the dollar volume of the (k — l)th transaction, defined as the price of the (k — Z)th transaction (in dollars, not ticks) times the number of shares traded (denominated in 100's of shares), hence dollar volume is denominated in $ 100's of dollars. To reduce the influence of outliers, if the share volume of a trade exceeds the 99.5 percentile of the empirical distribution of share volume for that stock, we set it equal to the 99.5 percentile.7

SP500k-1 = Three lags [I = 1, 2, 3] of five-minute continuously-compounded returns of the Standard and Poor's 500 index futures price, for the contract maturing in the closest month beyond the month in which transaction k — I occurred, where the return is computed with the futures price recorded one minute before the nearest round minute prior to tk-1 and the price recorded five minutes before this. More formally, we have:

where F(t-) is the S&P 500 index futures price at time t- (measured in seconds) for the contract maturing the closest month beyond the month of transaction k - I, and t- is the nearest round minute prior to time t (for example, if t is 10 : 35 : 47, then r is 10 : 35 : 00) .8

IBSk-1 = Three lags (I = 1, 2, 3) of an indicator variable that takes the value 1 if the (k - l)th transaction price is greater than the average of the quoted bid and ask prices at time tk-1, the value -1 if the (k -l)th transaction price is less than the average of the bid and ask prices at time tk-l and 0 otherwise, i.e.,

Whether the (k - l)th transaction price is closer to the ask price or the bid price is one measure of whether the transaction was buyer-initiated (IBSk-1 = 1) or seller-initiated (IBSk-1 = - 1). If the transaction price is at the midpoint of the bid and ask prices, the indicator is indeterminate (IBSk-l = 0).

Our specification of X'kß is then given by the following expression:

The variable  tk is included in Xk to allow for clock-time effects on the conditional mean of Z*k If prices are stable in transaction time rather than clock time, this coefficient should be zero. Lagged price changes are included to account for serial dependencies, and lagged returns of the S&P 500 index futures price are included to account for market-wide effects on price changes.

tk is included in Xk to allow for clock-time effects on the conditional mean of Z*k If prices are stable in transaction time rather than clock time, this coefficient should be zero. Lagged price changes are included to account for serial dependencies, and lagged returns of the S&P 500 index futures price are included to account for market-wide effects on price changes.

To measure the price impact of a trade per unit volume we include the term Tλ(Vk-1), dollar volume transformed according to the Box and Cox (1964) specification Tλ(•):

where λ  [0, 1] is also a parameter to be estimated. The Box-Cox transformation allows dollar volume to enter into the conditional mean nonlinearly, a particularly important innovation since common intuition suggests that price impact may exhibit economies of scale with respect to dollar volume, i.e., although total price impact is likely to increase with volume, the marginal price impact probably does not. The Box-Cox transformation captures the linear specification (λ = 1) and concave specifications up to and including the logarithmic function (λ = 0). The estimated curvature of this transformation will play an important role in the measurement of price impact.

[0, 1] is also a parameter to be estimated. The Box-Cox transformation allows dollar volume to enter into the conditional mean nonlinearly, a particularly important innovation since common intuition suggests that price impact may exhibit economies of scale with respect to dollar volume, i.e., although total price impact is likely to increase with volume, the marginal price impact probably does not. The Box-Cox transformation captures the linear specification (λ = 1) and concave specifications up to and including the logarithmic function (λ = 0). The estimated curvature of this transformation will play an important role in the measurement of price impact.

The transformed dollar volume variable is interacted with IBSk-1 an indicator of whether the trade was buyer-initiated (IBS k = 1), seller-initiated (IBSk = -1), or indeterminate (IBSk = 0). A positive β11 would imply that buyer-initiated trades tend to push prices up and seller-initiated trades tend to drive prices down. Such a relation is predicted by several informationbased models of trading, e-g., Easley and O'Hara (1987). Moreover, the magnitude of β11 is the per-unit volume impact on the conditional mean of Z*k, which may be readily translated into the impact on the conditional probabilities of observed price changes. The sign and magnitudes of β12 and β13is measure the persistence of price impact.

Finally, to complete our specification we must parametrize the conditional variance  To allow for clock-time effects we include

To allow for clock-time effects we include  tk, and since there is some evidence linking bid/ask spreads to the information content and volatility of price changes (see, for example, Glosten (1987), Hasbrouck (1988, 1991a,b), and Petersen and Umlauf (1990)), we also include the lagged spread ABk-1. Also, recall from Section 10.2.2 that the parameters α, β, and γ are unidentified without additional restrictions, hence we make the identification assumption that

tk, and since there is some evidence linking bid/ask spreads to the information content and volatility of price changes (see, for example, Glosten (1987), Hasbrouck (1988, 1991a,b), and Petersen and Umlauf (1990)), we also include the lagged spread ABk-1. Also, recall from Section 10.2.2 that the parameters α, β, and γ are unidentified without additional restrictions, hence we make the identification assumption that  = 1. Our variance parametrization is then:

= 1. Our variance parametrization is then:

In summary, our nine-state specification requires the estimation of 24 parameters: the partition boundaries α1…α8, ag, the variance parametersγ1and γ2 the coefficients of the explanatory variables β1,…, β 13, and the Box-Cox parameterγ The five-state specification requires the estimation of only 20 parameters.

10.5 The Maximum Likelihood Estimates

We compute the maximum likelihood estimators numerically using the algorithm proposed by Berndt, Hall, Hall, and Hausman (1974), hereafter BHHH. The advantage of BHHH over other search algorithms is its reliance on only first derivatives, an important computational consideration for sample sizes such as ours.

The asymptotic covariance matrix of the parameter estimates was computed as the negative inverse of the matrix of (numerically determined) second derivatives of the log-likelihood function with respect to the parameters, evaluated at the maximum likelihood estimates. We used a tolerance of 0.001 for the convergence criterion suggested by BHHH (the product of the gradient and the direction vector). To check the robustness of our numerical search procedure, we used several different sets of starting values for each stock, and in all instances our algorithm converged to virtually identical parameter estimates.

All computations were performed in double precision in an ULTRIX environment on a DEC 5000/200 workstation with 16 Mb of memory, using our own FORTRAN implementation of the BHHH algorithm with analytical first derivatives. As a rough guide to the computational demands of ordered probit, note that the numerical estimation procedure for the stock with the largest number of trades (IBM, with 206,794 trades) required only 2 hours and 45 minutes of cpu time.

In Table 10.2a, we report the maximum likelihood estimates of the ordered probit model for our six stocks. Entries in each of the columns labeled with ticker symbols are the parameter estimates for that stock, and to the immediate right of each parameter estimate is the corresponding z-statistic, which is asymptotically distributed as a standard normal variate under the null hypothesis that the coefficient is zero, i.e., it is the parameter estimate divided by its asymptotic standard error.

Table 10.2a shows that the partition boundaries are estimated with high precision for all stocks. As expected, the zstatistics are much larger for those stocks with many more observations. The parameters for  are also statistically significant, hence homoskedasticity may be rejected at conventional significance levels; larger bid/ask spreads and longer time intervals increase the conditional volatility of the disturbance.

are also statistically significant, hence homoskedasticity may be rejected at conventional significance levels; larger bid/ask spreads and longer time intervals increase the conditional volatility of the disturbance.

The conditional means of the Zk's for all stocks are only marginally affected by  tk. Moreover, the z-statistics are minuscule, especially in light of the large sample sizes. However, as mentioned above,

tk. Moreover, the z-statistics are minuscule, especially in light of the large sample sizes. However, as mentioned above,  t does enter into the

t does enter into the  expression significantly, hence clock time is important for the conditional variances, but not for the conditional means of Z*k. Note that this does not necessarily imply the same for the conditional distribution of the Zk' s, which is nonlinearly related to the conditional distribution of the Z*k’s. For example, the conditional mean of the Zk’s may well depend on the conditional variance of the Z*k's, so that clock time can still affect the conditional mean of observed price changes even though it does not affect the conditional mean of Z*k.

expression significantly, hence clock time is important for the conditional variances, but not for the conditional means of Z*k. Note that this does not necessarily imply the same for the conditional distribution of the Zk' s, which is nonlinearly related to the conditional distribution of the Z*k’s. For example, the conditional mean of the Zk’s may well depend on the conditional variance of the Z*k's, so that clock time can still affect the conditional mean of observed price changes even though it does not affect the conditional mean of Z*k.

More striking is the significance and sign of the lagged price change coefficients which are negative for all stocks, implying a tendency towards price reversals. For example, if the past three price changes were each one tick, the conditional mean of Z*k changes by

which are negative for all stocks, implying a tendency towards price reversals. For example, if the past three price changes were each one tick, the conditional mean of Z*k changes by  However, if the sequence of price changes was 1/-1/1, then the effect on the conditional mean is

However, if the sequence of price changes was 1/-1/1, then the effect on the conditional mean is , a quantity closer to zero for each of the security's parameter estimates.9

, a quantity closer to zero for each of the security's parameter estimates.9

Table 10.2a. Maximum likelihood estimates of the ordered probit model for transaction price changes of International Business Machines Corporation (IBM - 206,794 trades), Quantum Chemical Corporation (CUE - 26,927 trades), Foster Wheeler Corporation (FWC - 18,199 trades), Handy and Harman Company (HNH - 3,174 trades), Navistar International Corporation (NAV- 96,127 trades), and American Telephone and Telegraph Company (T-180,726 trades), for the period from fanuary 4, 1988, to December 30, 1988. Each z-statistic is asymptotically standard normal under the null hypothesis that the corresponding coefficient is zero.

aAccording to the ordered probit model, if the “virtual” price change Z*k is less than α1 then the observed price change is -4 ticks or less; if Z*k is between α1 and α2, then the observed price change is -3 ticks; and so on.

bThe ordered probit specification for FWC and HNH contains only five states (-2 ticks or less, -1, 0, +1, +2 ticks or more), hence only four α's were required.

cBox-Cox transformation of lagged dollar volume multiplied by the lagged buy/sell indicator, where the Box-Cox parameter λ is estimated jointly with the other ordered probit parameters via maximum likelihood. The Box-Cox parameter λ determines the degree of curvature that the transformation Tλ(•) exhibits in transforming dollar volume Vk before inclusion as an explanatory variable in the ordered probit specification. If λ = 1, the transformation Tλ(•) is linear, hence dollar volume enters the ordered probit model linearly. If λ= 0, the transformation is equivalent to log(•), hence the natural logarithm of dollar volume enters the ordered probit model. When λ is between 0 and 1, the curvature of Tλ(•) is between logarithmic and linear.

Table 10.2b. Cross-autocorrelation coefficients  , j = 1,…, 12, of generalized residuals

, j = 1,…, 12, of generalized residuals  with lagged generalized fitted price changes

with lagged generalized fitted price changes  k-j from the ordered probit estimation for transaction price changes of International Business Machines Corporation (IBM- 206,794 trades), Quantum Chemical Corporation (CUE - 26,927 trades), Foster Wheeler Corporation (FWC -18,199 trades), Handy and Harman Company (HNH - 3,174 trades), Navistar International Corporation (NAV- 96,127 trades), and American Telephone and Telegraph Company (T- 180,726 trades), for the period from fanuary 4, 1988 to December 30, 1988.a

k-j from the ordered probit estimation for transaction price changes of International Business Machines Corporation (IBM- 206,794 trades), Quantum Chemical Corporation (CUE - 26,927 trades), Foster Wheeler Corporation (FWC -18,199 trades), Handy and Harman Company (HNH - 3,174 trades), Navistar International Corporation (NAV- 96,127 trades), and American Telephone and Telegraph Company (T- 180,726 trades), for the period from fanuary 4, 1988 to December 30, 1988.a

aIf the ordered probit model is correctly specified,these cross-autocorrelations should be close to zero.

Table 10.2c. Score test statistics  , j = 1,…, 12, where

, j = 1,…, 12, where  under the null hypothesis of no serial correlation in the ordered probit disturbances

under the null hypothesis of no serial correlation in the ordered probit disturbances  using the generalized residuals

using the generalized residuals  from ordered probit estimation for transaction price changes of International Business Machines Corporation (IBM - 206,794 trades), Quantum Chemical Corporation (CUE - 26,927 trades), Foster Wheeler Corporation (FWC -18,199 trades), Handy and Harman Company (HNH - 3,174 trades), Navistar International Corporation (NAV - 96,127 trades), and American Telephone and Telegraph Company (T- 180,726 trades), for the period from fanuary 4, 1988, to December 30, 1988.a

from ordered probit estimation for transaction price changes of International Business Machines Corporation (IBM - 206,794 trades), Quantum Chemical Corporation (CUE - 26,927 trades), Foster Wheeler Corporation (FWC -18,199 trades), Handy and Harman Company (HNH - 3,174 trades), Navistar International Corporation (NAV - 96,127 trades), and American Telephone and Telegraph Company (T- 180,726 trades), for the period from fanuary 4, 1988, to December 30, 1988.a

aIf the ordered probit model is correctly specified, these test statistics should follow a  statistic which falls in the interval [0.00,3.84] with 95% probability.

statistic which falls in the interval [0.00,3.84] with 95% probability.

Note that these coefficients measure reversal tendencies beyond that induced by the presence of a constant bid/ask spread as in Roll (1984a). The effect of this “bid/ask bounce” on the conditional mean should be captured by the indicator variables IBSk-1, IBSk-2, and IBSk-3. In the absence of all other information (such as market movements, past price changes, etc.), these variables pick up any price effects that buys and sells might have on the conditional mean. As expected, the estimated coefficients are generally negative, indicating the presence of reversals due to movements from bid to ask or ask to bid prices. In Section 10.6.1 we shall compare their magnitudes explicitly, and conclude that the conditional mean of price changes is path- dependent with respect to past price changes.

The lagged S&P 500 returns are also significant, but have a more persistent effect on some securities. For example, the coefficient for the first lag of the S&P 500 is large and significant for IBM, but the coefficient for the third is small and insignificant. However, for the less actively traded stocks such as CUE, all three coefficients are significant and are about the same order of magnitude. As a measure of how quickly market-wide information is impounded into prices, these coefficients confirm the common intuition that smaller stocks react more slowly than larger stocks, which is consistent with the lead/lag effects uncovered by Lo and MacKinlay (1990a).

10.5.1 Diagnostics

A common diagnostic for the specification of an ordinary least squares regression is to examine the properties of the residuals. If, for example, a time series regression is well-specified, the residuals should approximate white noise and exhibit little serial correlation. In the case of ordered probit, we cannot calculate the residuals directly since we cannot observe the latent dependent variable Z*k and therefore cannot compute Z*k –  However, we do have an estimate of the conditional distribution of Z*k, conditioned on the Xk's, based on the ordered probit specification and the maximum likelihood parameter estimates. From this we can obtain an estimate of the conditional distribution of the

However, we do have an estimate of the conditional distribution of Z*k, conditioned on the Xk's, based on the ordered probit specification and the maximum likelihood parameter estimates. From this we can obtain an estimate of the conditional distribution of the  's from which we can construct generalized residuals

's from which we can construct generalized residuals  along the lines suggested by Gourieroux, Monfort, and Trognon (1985):

along the lines suggested by Gourieroux, Monfort, and Trognon (1985):

where  is the maximum likelihood estimator of the unknown parameter vector containing

is the maximum likelihood estimator of the unknown parameter vector containing  In the case of ordered probit, if Zk is in the jth state, i.e., Zk = sj, then the generalized residual

In the case of ordered probit, if Zk is in the jth state, i.e., Zk = sj, then the generalized residual  maybe expressed explicidy using the moments of the truncated normal distribution as

maybe expressed explicidy using the moments of the truncated normal distribution as

where Φ(•) is the standard normal probability density function and for notational convenience, we define αo ≡ -∞ and αm ≡ +∞. Gourieroux, Monfort, and Trognon (1985) show that these generalized residuals may be used to test for misspecification in a variety of ways. However, some care is required in performing such tests. For example, although a natural statistic to calculate is the first-order autocorrelation of the  's, Gourieroux et al. observe that the theoretical autocorrelation of the generalized residuals does not in general equal the theoretical autocorrelation of the

's, Gourieroux et al. observe that the theoretical autocorrelation of the generalized residuals does not in general equal the theoretical autocorrelation of the  's. Moreover, if the source of serial correlation is an omitted lagged endogenous variable (if, for example, we included too few lags of Zk in Xk), then further refinements of the usual specification tests are necessary.

's. Moreover, if the source of serial correlation is an omitted lagged endogenous variable (if, for example, we included too few lags of Zk in Xk), then further refinements of the usual specification tests are necessary.

Gourieroux et al. derive valid tests for serial correlation from lagged endogenous variables using the score statistic, essentially the derivative of the likelihood function with respect to an autocorrelation parameter, evaluated at the maximum likelihood estimates under the null hypothesis of no serial correlation. More specifically, consider the following model for our Z*k:

In this case, the score statistic  is the derivative of the likelihood function with respect to φ evaluated at the maximum likelihood estimates. Under the null hypothesis that φ = 0, it simplifies to the following expression:

is the derivative of the likelihood function with respect to φ evaluated at the maximum likelihood estimates. Under the null hypothesis that φ = 0, it simplifies to the following expression:

where

When φ= 0,  is asymptotically distributed as a

is asymptotically distributed as a  varíate. Therefore, using

varíate. Therefore, using  we can test for the presence of autocorrelation induced by the omitted variable Z*k-1 More generally, we can test the higher-order specification:

we can test for the presence of autocorrelation induced by the omitted variable Z*k-1 More generally, we can test the higher-order specification:

by using the score statistic

which is also asymptotically  under the null hypothesis that = 0.

under the null hypothesis that = 0.

For further intuition, we can compute the sample correlation  of the generalized residual

of the generalized residual  with the lagged generalized fitted values

with the lagged generalized fitted values  .k-j Under the null hypothesis of no serial correlation in the

.k-j Under the null hypothesis of no serial correlation in the  's, the theoretical value of this correlation is zero, hence the sample correlation will provide one measure of the economic impact of misspecification. These are reported in Table 10.2b for our sample of six stocks, and they are all quite small, ranging from -0.088 to 0.030.

's, the theoretical value of this correlation is zero, hence the sample correlation will provide one measure of the economic impact of misspecification. These are reported in Table 10.2b for our sample of six stocks, and they are all quite small, ranging from -0.088 to 0.030.

Finally, Table 10.2c reports the score statistics  , j = 1,…,12. Since we have included three lags of Zk in our specification of Xk, it is no surprise that none of the score statistics for j = 1, 2, 3 are statistically significant at the 5% level. However, at lag 4, the score statistics for all stocks except CUE and HNH are significant, indicating the presence of some serial dependence not accounted for by our specification. But recall that we have very large sample sizes so that virtually any point null hypothesis will be rejected. With this in mind, the score statistics seem to indicate a reasonably good fit for all but one stock, NAV, whose score statistic is significant at every lag, suggesting the need for respecification. Turning back to the cross-autocorrelations reported in Table 10.2b, we see that NAV's residual

, j = 1,…,12. Since we have included three lags of Zk in our specification of Xk, it is no surprise that none of the score statistics for j = 1, 2, 3 are statistically significant at the 5% level. However, at lag 4, the score statistics for all stocks except CUE and HNH are significant, indicating the presence of some serial dependence not accounted for by our specification. But recall that we have very large sample sizes so that virtually any point null hypothesis will be rejected. With this in mind, the score statistics seem to indicate a reasonably good fit for all but one stock, NAV, whose score statistic is significant at every lag, suggesting the need for respecification. Turning back to the cross-autocorrelations reported in Table 10.2b, we see that NAV's residual  has a -0.088 correlation with

has a -0.088 correlation with  k-4, the largest in Table 10.2b in absolute value. This suggests that adding Zk-4 as a regressor might improve the specification for NAV.

k-4, the largest in Table 10.2b in absolute value. This suggests that adding Zk-4 as a regressor might improve the specification for NAV.

There are a number of other specification tests that can check the robustness of the ordered probit specification, but they should be performed with an eye towards particular applications. For example, when studying the impact of information variables on volatility, a more pressing concern would be the specification of the conditional variance  If some of the parameters have important economic interpretations, their stability can be checked by simple likelihood ratio tests on subsamples of the data. If forecasting price changes is of interest, an R2-like measure can readily be constructed to measure how much variability can be explained by the predictors. The ordered probit model is flexible enough to accommodate virtually any specification test designed for simple regression models, but has many obvious advantages over OLS as we shall see below.

If some of the parameters have important economic interpretations, their stability can be checked by simple likelihood ratio tests on subsamples of the data. If forecasting price changes is of interest, an R2-like measure can readily be constructed to measure how much variability can be explained by the predictors. The ordered probit model is flexible enough to accommodate virtually any specification test designed for simple regression models, but has many obvious advantages over OLS as we shall see below.

10.5.2 Endogeneity of  tk and IBSk

tk and IBSk

Our inferences in the preceding sections are based on the implicit assumption that the explanatory variables Xk are all exogenous or predetermined with respect to the dependent variable Zk. However, the variable  tk is contemporaneous to Zk and deserves further discussion.

tk is contemporaneous to Zk and deserves further discussion.

Recall that Zkis the price change between trades at time tk-1 and time tk. Since  tk is simply tk — tk-1, it may well be that

tk is simply tk — tk-1, it may well be that  tk and Zkare determined simultaneously, in which case our parameter estimates are generally inconsistent. In fact, there are several plausible arguments for the endogeneity of

tk and Zkare determined simultaneously, in which case our parameter estimates are generally inconsistent. In fact, there are several plausible arguments for the endogeneity of  tk (see, for example, Admati and Pfleiderer (1988), 1989) and Easley and O'Hara (1992) ). One such argument turns on the tendency of floor brokers to break up large trades into smaller ones, and time the executions carefully during the course of the day or several days. By “working” the order, the floor broker can minimize the price impact of his trades and obtain more favorable execution prices for his clients. But by selecting the times between his trades based on current market conditions, which include information also affecting price changes, the floor broker is creating endogenous trade times.

tk (see, for example, Admati and Pfleiderer (1988), 1989) and Easley and O'Hara (1992) ). One such argument turns on the tendency of floor brokers to break up large trades into smaller ones, and time the executions carefully during the course of the day or several days. By “working” the order, the floor broker can minimize the price impact of his trades and obtain more favorable execution prices for his clients. But by selecting the times between his trades based on current market conditions, which include information also affecting price changes, the floor broker is creating endogenous trade times.

However, any given sequence of trades in our dataset does not necessarily correspond to consecutive transactions of any single individual (other than the specialist of course), but is the result of many buyers and sellers interactingwith the specialist. For example, even if a floor broker were working a large order, in between his orders might be purchases and sales from other floor brokers, market orders, and triggered limit orders. Therefore, the  tk's also reflect these trades, which are not necessarily information- motivated.

tk's also reflect these trades, which are not necessarily information- motivated.

Another more intriguing reason that  tk may be exogenous is that floor brokers have an economic incentive to minimize the correlation between

tk may be exogenous is that floor brokers have an economic incentive to minimize the correlation between  tk and virtually all other exogenous and predetermined variables. To see this, suppose the floor broker timed his trades in response to some exogenous variable also affecting price changes, call it “weather.” Suppose that price changes tend to be positive in good weather and negative in bad weather. Knowing this, the floor broker will wait until bad weather prevails before buying, hence trade times and price changes are simultaneously determined by weather. However, if other traders are also aware of these relations, they can garner information about the floor broker's intent by watching his trades and by recording the weather, and trade against him successfully. To prevent this, the floor broker must trade to deliberately minimize the correlation between his trade times and the weather. Therefore, the floor broker has an economic incentive to reduce simultaneous equations bias! Moreover, this argument applies to any other economic variable that can be used to jointly forecast trade times and price changes. For these two reasons, we assume that

tk and virtually all other exogenous and predetermined variables. To see this, suppose the floor broker timed his trades in response to some exogenous variable also affecting price changes, call it “weather.” Suppose that price changes tend to be positive in good weather and negative in bad weather. Knowing this, the floor broker will wait until bad weather prevails before buying, hence trade times and price changes are simultaneously determined by weather. However, if other traders are also aware of these relations, they can garner information about the floor broker's intent by watching his trades and by recording the weather, and trade against him successfully. To prevent this, the floor broker must trade to deliberately minimize the correlation between his trade times and the weather. Therefore, the floor broker has an economic incentive to reduce simultaneous equations bias! Moreover, this argument applies to any other economic variable that can be used to jointly forecast trade times and price changes. For these two reasons, we assume that  tk is exogenous.

tk is exogenous.

We have also explored some adjustments for the endogeneity of  tk along the lines of Hausman (1978) and Newey (1985), and our preliminary estimates show that although exogeneity of

tk along the lines of Hausman (1978) and Newey (1985), and our preliminary estimates show that although exogeneity of  tk may be rejected at conventional significance levels (recall our sample sizes), the estimates do not change much once endogeneity is accounted for by an instrumental variables estimation procedure.

tk may be rejected at conventional significance levels (recall our sample sizes), the estimates do not change much once endogeneity is accounted for by an instrumental variables estimation procedure.

There are, however, other contemporaneous variables that we would like to include as regressors which cannot be deemed exogenous (see the discussion of IBSk in Section 10.6.2 below), and for these we must wait until the appropriate econometric tools become available.

10.6 Applications

In applying the ordered probit model to particular issues of the market microstructure, we must first consider how to interpret its parameter estimates from an economic perspective. Since ordered probit may be viewed as a generalization of a linear regression model to situations with a discrete dependent variable, interpreting its parameter estimates is much like interpreting coefficients of a linear regression: the particular interpretation depends critically on the underlying economic motivation for including and excluding the specific regressors.

In a very few instances, theoretical paradigms might yield testable implications in the form of linear regression equations, e.g., the CAPM's security market line. In most cases, however, linear regression is used to capture and summarize empirical relations in the data that have not yet been derived from economic first principles. In much the same way, ordered probit may be interpreted as a means of capturing and summarizing relations among price changes and other economic variables such as volume. Such relations have been derived from first principles only in the most simplistic and stylized of contexts, under very specific and, therefore, often counterfactual assumptions about agents' preferences, information sets, alternative investment possibilities, sources of uncertainty and their parametric form (usually Gaussian), and the timing and allowable volume and type of trades.10Although such models do yield valuable insights about the economics of the market microstructure, they are too easily rejected by the data because of the many restrictive assumptions needed to obtain readily interpretable closed-form results.

Nevertheless, the broader implications of such models can still be “tested” by checking for simple relations among economic quantities, as we illustrate in Section 10.6.1. However, some care must be taken in interpreting such results, as in the case of a simple linear regression of prices on quantities which cannot be interpreted as an estimated demand curve without imposing additional economic structure.

In particular, although the ordered probit model can shed light on how price changes respond to specific economic variables, it cannot give us economic insights beyond whatever structure we choose to impose a priori. For example, since we have placed no specific theoretical structure on how prices are formed, our ordered probit estimates cannot yield sharp implications for the impact of floor brokers “working” an order (executing a large order in smaller bundles to obtain the best average price). The ordered probit estimates will reflect the combined actions and interactions of these floor brokers, the specialists, and individual and institutional investors, all trading with and against each other. Unless we are estimating a fully articulated model of economic equilibrium that contains these kinds of market participants, we cannot separate their individual impact in determining price changes. For example, without additional structure we cannot answer the question: What is the price impact of an order that is not “worked”?

However, if we were able to identify those large trades that did benefit from the services of a floor broker, we could certainly compare and contrast their empirical price dynamics with those of “unworked” trades using the ordered probit model. Such comparisons might provide additional guidelines and restrictions for developing new theories of the market microstructure. Interpreted in this way, the ordered probit model can be a valuable tool for uncovering empirical relations even in the absence of a highly parametrized theory of the market microstructure. To illustrate this aspect of ordered probit, in the following section we consider three specific applications of the parameter estimates of Section 10.5: a test for order-flow dependence in price changes, a measure of price impact, and a comparison of ordered probit to ordinary least squares.

10.6.1 Order-Flow Dependence

Several recent theoretical papers in the market microstructure literature have shown the importance of information in determining relations between prices and trade size. For example, Easley and O'Hara (1987) observe that because informed traders prefer to trade larger amounts than uninformed liquidity traders, the size of a trade contains information about who the trader is and, consequently, also contains information about the traders' private information. As a result, prices in their model do not satisfy the Markov property, since the conditional distribution of next period's price depends on the entire history of past prices, i.e., on the order flow. That is, the sequence of price changes of 1/-1/1 will have a different effect on the conditional mean than the sequence -1/1/1, even though both sequences yield the same total price change over the three trades.

One simple implication of such order-flow dependence is that the coefficients of the three lags of Zk's are not identical. If they are, then only the sum of the most recent three price changes matters in determining the conditional mean, and not the order in which those price changes occurred. Therefore, if we denote by βp the vector of coefficients [β2 β3 β4]' of the lagged price changes, the null hypothesis H of order-flow independence is simply:

This may be recast as a linear hypothesis for βp, namely Aβp = 0, where

Then under H, we obtain the following test statistic:

where  is the estimated asymptotic covariance matrix of

is the estimated asymptotic covariance matrix of  The values of these test statistics for the six stocks are: IBM = 11,462.43, CUE = 152.05, FWC = 446.01, HNH = 18.62, NAV = 1,184.48, and T = 3,428.92. The null hypothesis of order-flow independence may be rejected at all the usual levels of significance for all six stocks. These findings support Easley and O'Hara's observation that information-based trading can lead to pathdependent price changes, so that the order flow (and the entire history of other variables) may affect the conditional distribution of the next price change.