One pattern of suppression is that of omission.

Patricia Hill Collins (feminist theorist)1

The people want democracy, real democracy, Mr. Dies, and they look toward Hollywood to give it to them because they don’t get it any more in their newspapers. And that’s why you’re out here, Mr. Dies—that’s why you want to destroy the Hollywood progressive organizations—because you’ve got to control this medium if you want to bring fascism to this country.

Dorothy Parker (writer)2

It seemed as though the writers of the American situation comedy Leave It to Beaver knew from the start that the show would be on the air—without interruption—for generations to come. Its first episode, broadcast in 1957, suggested as much. “Beaver Gets Spelled” began with a voice-over by Beaver’s father, Ward Cleaver. “When you were young,” the omniscient male voice intoned, you had “values that nothing could change. An ice cream cone was a snow-capped mountain of sheer delight. An autographed baseball was more precious than rubies. And a note from the teacher meant only one thing: disaster.”3 Against images of a soda jerk handing an ice cream cone to an eager Beaver; Beaver and two friends marveling over an autographed baseball in a tree-filled park; and a female teacher scolding a chastened Beaver, the voice-over conjured a utopian past for the boy’s present.

The person—the you—this episode both addressed and remembered was male (someone for whom an autographed baseball was more precious than a gem), American (as the iconic game of baseball), middle class (a person who could afford ice cream cones and professional ball games), and white (a child for whom school discipline was a comic episode in an otherwise idyllic childhood). In less than fifty seconds, this montage conveyed a vision of 1950s America rooted in the suburban tranquility, consumerism, and masculine order symbolizing the American family and its values. The episode merged present and future in its vision of America, as the moment when viewers “were young” combined with a past, the narrator confidently asserted, for which they would someday most assuredly yearn.

In the decades following the emergence of American television, viewers were encouraged to remember, through similarly rose-colored lenses, the medium’s early period as a conflict-free era when women were happy with their domestic lot and African Americans with their subordinate place in American society. Judging from the scenes that flickered across television screens in the 1950s and 1960s, American culture mirrored a Cold War consensus. In it, the consumer was king and the new medium’s content a reflecting pool for the hopes and dreams of white veterans and women eager to return to the domestic sphere and get on with the business of having babies, settling into their new suburban homes, and buying the mass-produced items being churned out by a booming postwar economy. Other sitcoms of the era celebrated these postwar American values in similarly suburban settings, in Westerns that portrayed the individualistic triumphs of white masculinity, and in police procedurals that taught viewers to fear urban areas increasingly associated with disruptive black residents. Much like the inaugural episode of Leave It to Beaver, mass-mediated narratives of television’s rise presented images from an untroubled, halcyon epoch, full of wholesome content and broad social agreement about American “values nothing could change.”

Many of those watching television in 1957, when this episode aired, or in the years that followed had no reason to suspect that these images of a nation that shared universal values and happy consensus at the end of World War II were made possible by ongoing acts of repression. Television shows did not hint at the circumstances that prevented people of color from appearing in the medium’s imaginings of American life only in demeaning roles—as cooks in Westerns, like Bonanza’s Hop Sing, and the butts of racialized humor in the sitcom Amos ’n’ Andy. Instead, the absence of any other images reassured white viewers that racial hierarchies were natural and just. Black people either entertained white people on variety shows or turned up as domestic servants and mammy figures in the lives of white people. In Beulah, a series about a black housekeeper and cook for a white family, the series’ titular character was played by a succession of brilliant African American actresses—Ethel Waters, Hattie McDaniel, and Louise Beavers—unable to find roles other than maids. Women were consigned to racially stratified domestic roles: by the mid-1950s, even The Goldbergs’ formidable Molly—a physically and emotionally large, working-class, Jewish matriarch—had been reduced to uttering clichés about the perverted, un-American desires of women who worked outside the home. No one seemed to notice when immigrants all but disappeared from small screens.

Contrary to popular beliefs, the images that appeared on American television after 1950 were not simply reflections of American culture. They were products of suppression, fear, and, eventually, self-censorship. This book is about how the values and happy consensus viewers saw on their television screens came about. It is about what seemed possible for the new medium in 1945, as progressives gathered in the broadcast capital of New York City, and how those possibilities were eliminated within a ten-year period. While what happened to the ‘41’ shows us the limits of that rosy image of TV consensus, their efforts were not limited to TV alone: they were cultural workers across media and took advantage of all the means by which mass cultural forms could be used in the service of progressivism. Although most of the book’s action takes place in the past, its resonance for the present and the future lies in the lessons this story can teach us about the impact of political struggles over new media and the consequences of allowing one set of perspectives to dominate all others.

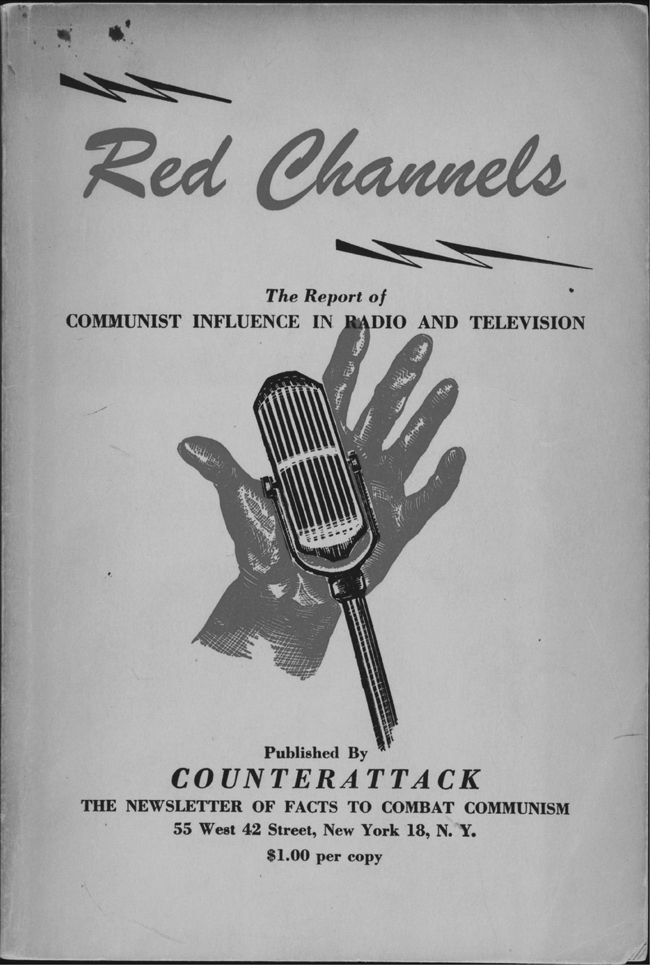

To dislodge the notion that what appeared on television screens after 1950 resulted from some broad social agreement, this book tell two overlapping stories. One story centers on the white, native-born anti-communists who created and carried out the blacklist in television, the principal means by which anti-communists were able to impose their version of Americanism on television. Three men in particular, Kenneth Bierly, John Keenan, and Theodore Kirkpatrick, former FBI agents, founded a group that called itself the American Business Consultants in 1947. They coined an anti-communist tautology—“factual information”—to distinguish between the media they wrote and disseminated and what they described as the Communist propaganda of anti-racist progressives. Unfettered by journalistic accountability to facts, these men published the influential anti-communist newsletter CounterAttack and the book Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television. As former agents of the FBI, Bierly, Keenan, and Kirkpatrick drew on the power of the anti-communist security state in their efforts to impose stories favoring the political and economic objectives they shared with others who aspired to G-Man masculinity.

The second story documents the dramatically different perspectives of a group of progressive women who had been influencing media production in New York City in the 1930s and 1940s. In 1950, the American Business Consultants identified 41 women and 110 men as “members or sympathizers” of the Communist Party in Red Channels, the publication that became the central vehicle for the ensuing blacklist.4 Although Red Channels listed far more men in its pages than women, anti-communists singled out women for their initial attacks. These women were engaged in oppositional cultural production: they criticized anti-communist norms of gender, race, class, and nation and resisted the imposition of these norms in their personal, professional, and political lives. Playwright Lillian Hellman’s father once told Hellman that she “lived within a question mark,” referring to the profound curiosity that caused her to constantly ask questions about the world that surrounded her.5 The Broadcast 41 were all women who lived within similar question marks, asking questions and creating new ways of seeing a world that was in the midst of massive and divisive changes. Their contributions to American culture, and what happened to them in the harsh dawning of the Cold War era, show how the consensus American television presented in the 1950s existed only by virtue of anti-communists’ ability to criminalize dissent, drive dissenters from media industries, and then make it all but impossible to remember that dissent had existed in the first place.

These repressed realities of resistance are far richer than most versions of American television’s history allow. Sociologist Herman Gray observes that in the early days of television, “Blacks appeared primarily as maids, cooks, ‘mammies,’ and other servants, or as con artists and deadbeats.”6 Gray is right, but as this book shows, those stereotypes were not reproduced without a fight. Not all of those present at the birth of American television in New York City willingly acquiesced to the rigid norms imposed by the American Business Consultants or subsequent Cold War prescriptions for race and gender. Not all of those working in and around the new industry were white, male, or middle class. Indeed, in 1945, it was not pre-ordained that the content of American television would center the perspectives of Cold War masculinities rather than the chorus of heterogeneous, politically progressive voices that were in conversation with each other in media industries in New York City.

Laying bare the conflict between progressive women and the anti-communists who opposed them not only challenges the belief that what appeared on television screens reflected what was in the hearts and minds of American viewers in 1950, it shows that struggles over television’s stereotypes predated the social movements of the 1960s. Indeed, accounts of the Broadcast 41’s lives and work reveal the contours of another history of American television, one that has been clouded by the legacies of anti-communism. In this counterfactual version of television’s history, people of principle and courage tried to present the perspectives of diverse groups of Americans to national audiences in the years following World War II. Their efforts offer a new context for understanding contemporary debates about the need for heterogeneous voices and ideas in media production and thus in media representations. The Broadcast 41’s experiences remind us of the weighty cultural and political work done by the stories we hear, and the people and ideas that are permitted to enter our screens, homes, and hearts. Without this context, we undertake the struggle over complex and respectful representations of all people thinking that we are the beginning, when in reality we participate in a long line of resistance.

There is cruel irony in the fact that this book depicts the repression of the histories, to borrow a phrase from activist and scholar Angela Y. Davis, of a group of women who were themselves deeply conscious of forces in the past that had conspired to exclude dissenting perspectives from historical view.7 The Broadcast 41 and other progressives knew that the blacklist was a mechanism for throttling dissent and preventing its dissemination and recollection. Many of them lived long enough to watch as their perspectives were erased by histories of the medium’s “Golden Age,” stories told from the points of view of the white men who subsequently went on to prosper in Cold War television, accounts popularized by scholars and journalists who listened to those men, affirmed their experiences, and universalized their stories.8 We should not be surprised that when we view the history of television through lenses fashioned by anti-communism, what we see is the absence of anyone but white men and a handful of white women, most of them stars. The continued erasure of the Broadcast 41 and other progressives in media industries, as feminist theorist Patricia Hill Collins reminds us, is an ongoing process of suppression.

❖ ❖ ❖

Everything about you—your race and gender, where and how you were raised, your temperament and disposition—can influence whom you meet, what is confided to you, what you are shown, and how you interpret what you see. My identity opened some doors and closed others. In the end, we can only do the best we can with who we are, paying close attention to the ways pieces of ourselves matter to the work while never losing sight of the most important questions.

Matthew Desmond (sociologist)9

I was rebellious when I was four years old, I think, and a nuisance, too. All rebels are nuisances too.

Lillian Hellman (writer)10

Unlike later generations of writers, directors, and producers—almost exclusively white and economically privileged, mostly male—the Broadcast 41’s lived experiences hinted at the diversity of American culture in urban areas like New York City in the first half of the twentieth century. Four of the Broadcast 41 were African American (Shirley Graham, Lena Horne, Hazel Scott, Fredi Washington); one was Mexican-American (María Marguerita Guadalupe Teresa Estela Bolado Castilla y O’Donnell, a dancer and actress who performed as “Margo”). Most of the women listed in Red Channels in 1950 were from working-class or immigrant backgrounds (sometimes both). More than a third were Jewish women from politically progressive urban enclaves. As artists and cultural workers, they were aware that they were being represented in ways that were untrue to their lived experiences and degrading. Hollywood forced white women like Judy Holliday to play dumb blondes in order to mask their intelligence. The film industry cast African Americans strictly as maids or hypersexualized women, stereotypes that Lena Horne, Hazel Scott, and Fredi Washington fought against for the entirety of their careers.

Their experiences of being excluded encouraged the Broadcast 41 to participate in progressive social networks across media industries. Kate Mostel, wife of blacklisted actor Zero Mostel and close friend of blacklisted actress Madeline Lee, once said that living in New York City made her feel as though “there are only 200 people in the world. They all know each other.”11 Progressives like Mostel encountered each another personally, politically, and professionally across spheres of cultural production in New York City. Writers Dorothy Parker and Lillian Hellman worked together in theater, forging a friendship surprising to those who believed that independent, strong-willed women could not get along.12 Blacklisted actresses Madeline Gilford and Jean Muir were close friends whose husbands worked together in the American Federation of Television and Radio Actors (AFTRA).

Like other women of their era who enjoyed economic advantages, Broadcast 41 members Lena Horne and Dorothy Parker attended benefits like a fundraiser for the United Negro and Allied Veterans of America, intended to help African American veterans get the cash payments they were owed when they left military service.13 After a dinner party they both attended in Manhattan, actress Rose Hobart became fast friends with actress Selena Royle after Royle publicly reprimanded Hobart’s verbally abusive (and soon-to-be former) husband.14 Actress and journalist Fredi Washington and musician and actress Hazel Scott traveled in the same circles in Harlem: Washington’s sister was politician Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.’s first wife; Hazel Scott was his second.

These women and their friends partied at Café Society, a hangout frequented by progressives founded by Communist Party member Barney Josephson because he “wanted to own a club where blacks and whites could work together as entertainers and a mixed audience could sit out front together to watch the show.”15 Years later, in her one-woman show, Lena Horne described how much it meant to her to have “her beautiful sister Billie Holliday” performing at one of Josephson’s clubs, while her “other beautiful sister Hazel Scott” performed at the other.16

The Broadcast 41 often admired one another’s work and relished opportunities to work with each other. Dorothy Parker, Lena Horne, Fredi Washington, and Shirley Graham counted blacklisted actor Paul Robeson among their circle of friends. Later, the FBI took great pains to investigate all those who moved within Robeson’s international orbit. Lena Horne admired actress Ella Logan’s singing and made a point to keep in touch with her in New York and Los Angeles.17 Lillian Hellman was a fan of Judy Holliday’s work with the comedy group the Revuers.18

Many of those listed in Red Channels knew one another from working on writer, director, and actor Gertrude Berg’s popular radio series, The Goldbergs. Actress Louise Fitch’s first husband was character actor Richard H. Harris, who played Jake in the radio series; actor and union leader Philip Loeb played husband Jake in the television series; Fredi Washington had a recurring role as well; Adelaide Klein was on the show; as a young man, writer Garson Kanin appeared on the radio program; blacklisted screenwriter and novelist Abraham Polonsky got his start writing for Berg; and actress Madeline Lee appeared in the television series even after her name appeared in Red Channels.

Obligations of citizenship also brought the Broadcast 41 into contact with one another. During the war, Margaret Webster, Selena Royle, Hester Sondergaard, and Lillian Hellman shared billing in a program sponsored by the Artists’ Front to Win the War. Dozens of other progressives supported and attended a broad array of cultural and political events that would later be used by anti-communists to blacklist them.19 Actress Anne Revere was a leader in efforts to defend the Hollywood Ten (a group of white, male writers, directors, and producers who refused to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee [the HUAC] and were jailed as a result in 1950), while Lena Horne and Hazel Scott used their stardom to promote civil rights. Over the course of a life cut short by FBI surveillance and harassment, concert pianist Ray Lev lent her talent to a procession of political events, eventually running for City Council in Manhattan as an American Labor Party candidate.

The Broadcast 41 knew about one another, even when they did not know each other intimately, and they understood their work to be part of a much larger conversation about popular culture’s role in a democracy. Critics and producers of popular culture themselves, the Broadcast 41 saw in mass media and popular culture new opportunities to effect social change and to influence American culture on a massive scale, ushering innovative and diverse perspectives, ideas, and representations onto the historical stage. Outsiders in a variety of media industries, the Broadcast 41 understood their perspectives were one among many views on the social worlds that surrounded them.

Alienated from mass-mediated narratives that represented women, people of color, queer people, and immigrants as inferior, abnormal, and subversive, the Broadcast 41 wanted to represent perspectives that had been hitherto unrepresented, seeking ways to break out of forms of thinking and representing that, in sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s words, reflected a “monopoly over the universal.”20 To monopolize the universal in the case of television was to assume that there was a singular perspective from which an American experience could be told, a standpoint that invisibly regulated what could be seen and represented. The anti-communist perspective that achieved dominance during the 1950s was such a monopoly, reflecting the standpoint of white, native-born, Cold War masculinity. From this vantage point, the lives of people of color, women, and immigrants were largely hidden, or reduced to stereotypes confirming their inherent inferiority.

To challenge this monopoly, progressives like the Broadcast 41 emphasized the heterogeneity of American life rather than its alleged uniformity, drawing on historical and personal reservoirs of richly varying racial, ethnic, religious, gender, and class backgrounds to do so. These perspectives were refined in the crucible of Popular Front organizations, a movement that cultural studies scholar Michael Denning describes as “the insurgent social movement forged from the labor militancy of the fledgling CIO, the anti-fascist solidarity with Spain, Ethiopia, China, and the refugees from Hitler, and the political struggles on the left wing of the New Deal.”21 Influenced by the vibrant art and popular culture that emerged from the Popular Front, the Broadcast 41’s experiences of the Depression further caused them to wrestle with capitalism’s systemic inequalities. Republican Spain’s war against fascism moved many of the Broadcast 41 to political action. Most of these women strongly identified with the progressivism of the left wing of the New Deal, inspired by the Popular Front’s constellation of communist-inspired and led anti-racist organizations. They believed in peaceful democracy, and they translated their passion into action, campaigning for the rights of African Americans, women, immigrants, and workers.

The Broadcast 41 called themselves progressives, a term that from roughly 1934 (when the Comintern announced its Popular Front strategy for fighting fascism) until the end of World War II, to borrow cultural historian Alan Wald’s definition, referred to “a radical who was willing to collaborate with Communists and who looked on the Soviet Union favorably as a force for peace and anticolonialism.”22 While this definition was obvious to those on the organized left anxious to distinguish among communists, socialists, Trotskyists, anarchists, and New Dealers, in the early years of the Cold War, anti-communists increasingly identified anyone expressing opinions to the left of center as ideologically suspect and un-American. Although the term progressive was gradually redefined by the left as well as the right after World War II, throughout this book I use “progressive” as an umbrella term incorporating a range of the leftist political thought and alliances running throughout the Popular Front, before the Cold War reshaped its meaning.

While the perspectives of the Broadcast 41 bookend the following chapters, the middle section of this book describes the forces conspiring against the Broadcast 41 in the years before anti-communism became institutionalized in media. I use the verb conspire intentionally here, because as the postwar era gave way to the Cold War, anti-communists were nothing if not deliberate in their campaigns against progressives in broadcasting. Evangelical in their beliefs, the founders of the American Business Consultants viewed America from a standpoint they considered natural, uncontroversial, and unassailable because their superiority was conferred on them by God. To question the anti-democratic and often illegal behaviors of anti-communists, to challenge the belief that women and people of color were biologically inferior to white men, to have been at any point in time infected by the politics of the Popular Front was to be in the eyes of anti-communists forever potentially treasonous and un-American.

Anti-communists in government, industry, and the private sector (including the American Legion, a veterans’ organization, and the Boy Scouts) had been monitoring progressives since before the end of World War I, creating lists of people, groups, and organizations they claimed were communists or communist sympathizers (known as “fellow-travelers” because they moved in overlapping progressive cultural and political circles). Activist and white supremacist Elizabeth Dilling created the first anti-communist political blacklist in The Red Network (1934).23 The blacklist orchestrated by anti-communists built off her model, and it enveloped media along with government, education, manufacturing, and other industries considered vulnerable to communist infiltration. Anti-communists in government and the private sector shared their lists with likeminded organizations, using this information to attack, smear, defund, and otherwise undermine the reputations of progressives and the organizations and institutions with which they were associated. Anti-communists and progressives recognized that this new medium, whose audiences were anticipated to be so vast as to make all previous audiences tiny in comparison, had the potential to create what Bourdieu describes as a “single, central, dominant, in a word, quasi-divine, point of view.”24

Anti-communists used the blacklist to create this divine point of view by eliminating progressives from the industry, forging a lasting link between criticism and controversy on one hand and communism and treason on the other. To be critical of white supremacy was to be communist; to be communist was to be a treacherous and un-American. These links imposed conditions of conformity within the television industry, generating the appearance of postwar consensus on television screens that provided cover for anti-communists’ distinctly undemocratic political activities. Anti-communists made it dangerous to even remember progressive ideas or the people who had held them by repressing the history of the vibrant and contentious field of perspectives that had attended the birth of television in New York City.

To counter the forms of repression that linger many years after the events in this book took place, The Broadcast 41: Women and the Anti-Communist Blacklist reflects on the birth of television not from the center of the television industry, but from its margins, where progressive ideas and culture had flourished in the 1930s and 1940s. In doing so, it understands the content of American television not as the product of consensus, but as the effect of a culture war whose casualties included the perspectives of a generation of progressive women. By documenting the perspectives of these women and the blacklist that anti-communists used to suppress them, this book takes a first step toward undoing their erasure from history.

By providing a counterfactual history of what American television might have looked like had anti-communists not succeeded in eradicating the perspectives of the Broadcast 41 from the industry, this book vividly illustrates what American culture lost when anti-communists succeeded in driving all but a very narrow swath of perspectives from the new medium of television. The Broadcast 41’s stories challenge us to think about what the new medium might have become had anti-communists not won this culture war. What would it have meant to create programs where women, people of color, and immigrants were neighbors and schoolmates, colleagues and supervisors, people with agency and complexity and not secondary and subservient to the lives and objectives of G-Men and their allies? What might American culture have looked like if stories about democracy and equality had dominated rather than narratives about homicide?

❖ ❖ ❖

After a hundred years of the modern struggle for women’s equality Soviet women are urged in their magazines to educate themselves and grow, to fulfill their production quotas and thus add to the happiness and well-being of the nation; while judging from the number of square feet given over to the subject in every issue of the Ladies Home Journal, the highest ideal of American womanhood is smooth, velvety, kissable hands.

Betty Millard (writer, artist, feminist)25

The fad of denouncing the American woman has another effect which is more tangible and even less funny than its effect on people’s feelings. There is today a real danger that resentment against women, especially against women in industry, will be promoted into an issue by professional agitators. Many know that this is becoming a serious threat.

Alice Sheldon (author)26

Historian Stephanie Coontz once observed that people in the United States treat sitcoms like Leave It to Beaver as if they were documentaries, describing the traditional family or its family values through images drawn directly from representations originating on television screens.27 This observation has stuck with me over the years, causing me to think about why conservatives of all genders persist in endorsing values that privilege a family ideal grounded in so many exclusions. Even when their lived experiences do not match those of the idyllic American family, as was the case with politicians like Ronald Reagan, Strom Thurmond, Sarah Palin, and Donald Trump and pundits like Rush Limbaugh and Bill O’Reilly, conservatives stubbornly cling to these images. When I began researching representations of family on television, I jokingly referred to the tendency of mass media to represent the American family in terms supplied by television as the “Leave it to Beaver syndrome,” a condition caused by years of watching reruns of family sitcoms, viewings that induced nostalgia among many white people for a form of family that was historically contingent and far from universal.

After researching this book, I am less inclined to treat this suggestion as a joke. In the second half of the 1940s, anti-communists—including powerful organizations and institutions like the FBI, the HUAC, the American Legion, the National Association of Manufacturers, the Catholic Church, Chambers of Commerce, and myriad others—initiated an apocalyptic battle over their definition of Americanism. Some of them believed that this war was reality; others were swift to recognize the political and economic utility of frightening people into giving up fundamental rights in exchange for promises of security. Arguing that the ends (stemming what anti-communists depicted as a rising tide of atheistic communism) justified the means (unconstitutional, illegal, and often brutal forms of surveillance and retaliation), anti-communists set out to make sure that the new medium of television would be free of progressive influences.

Television served as a crucial battleground over American values for a number of reasons. In the first place, anti-communists feared the intrusion of this new medium into American homes and its effects on domestic security. J. Edgar Hoover told the HUAC, “The best antidote to communism is vigorous, intelligent, old-fashioned Americanism.” For anti-communists, the home was the most important front in the war over old-fashioned Americanism.28 Hoover considered the family the first line of defense against the dangerous perspectives of his critics. Ignoring the historical variability of family forms, as well as demographic changes that had occurred during the tumultuous first half of the twentieth century, anti-communists defined the American family as “the old-fashioned loyalty of one man and one woman to each other and their children … the basis, not only of society, but of all personal character and progress,” as anti-communist Elizabeth Dilling put it.29

Gender and race lay at the heart of anti-communists’ anxieties about a family form they diagnosed as being in crisis at the war’s end. Following on the heels of the Depression, a catastrophic global economic disaster that challenged conservative notions of American identity, a successful war effort required the labor of women and men of color in industries that had previously excluded them. As women and people of color joined in wartime production, moving into positions previously reserved for white men, norms of race and gender were temporarily waived, a form of social destabilization, according to political theorist Cynthia Enloe, typical of periods of militarized conflict.30 At the end of the war, white anti-communist men and women mobilized to restore the social hierarchies that had existed before 1941, expecting that white women would cede their freedoms to returning veterans and that African Americans who had fought a war against fascism in Europe would quietly accept the injustices of racism at home.

The anti-communist movement drew much of its strength from organizations that represented white veterans of war. These organizations encouraged white men traumatized by World War II to understand the changes that had happened in their absence as evidence of subversive, communistic influence. Veterans who had returned home to find families, homes, and communities changed in their absence were urged by anti-communist ideologues to redirect their anger, resentment, and pain toward American women and African Americans in particular, a tactic still used today. In exchange, anti-communists promised them nothing less than the restoration of their birthright as white men. According to historian Katherine Belew, “The return of [white] veterans from combat appears to correlate more closely with Klan membership than any other historical factor,” highlighting the link between all-white veterans’ organizations and renewed racist violence.31 Indeed, in the years following World War II, veterans’ organizations, working closely with fellow anti-communist institutions and organizations, redoubled their efforts to maintain segregation in American society and media industries, playing a key role in supporting and expanding the blacklist on television.32

The anti-communist movement was unified in its hatred of women who stepped out of the social roles conservatives approved for them. In their efforts to roll back changes that had begun well before the war, and as the shadow of the Cold War lengthened, images of a white Rosie the Riveter giving her patriotic all to support the war effort gave way to representations of white women whose wartime freedoms had compromised their femininity. One GI quoted in a New York Times Magazine article lavished praise on the infinite superiority of British girls who knew their place, “who think a man is important.… these girls over here don’t want so many things. You get married to a girl back home and pretty soon she’s got to have a fur coat and a washing machine and your car’s got to be better looking than the one next door. You could bring a British girl ‘some little thing’ and you’d think you’d brought them a diamond bracelet.”33 Another veteran observed of his German girlfriend that, despite the fact she was “much better educated than I am and comes from a better family,” she remained more subservient than her American counterpart: “when I get up in the morning I find my shoes shined and trousers pressed. Can you imagine an American woman doing that for you? Kee-rist, my own little sister wouldn’t do that even for her old man!”34

Anti-communists held white women who defied conservative norms responsible for an ostensible decline in the American family’s morals. Philip Wylie, a novelist, screenwriter, and commentator on American culture, first published his Generation of Vipers in 1943, but the book’s popularity surged after World War II. Stimulated by new and unnatural cultural and political freedoms, American women, Wylie floridly maintained, had abandoned the only labor they were biologically suited for: “The machine has deprived her of social usefulness; time has stripped away her biological possibilities and poured her hide full of liquid soap; and man has sealed his own soul beneath the clamorous cordillera by handing her the checkbook and going to work in the service of her caprices.”35 Blaming “moms” and “momism” for the moral shortcomings of American culture, Wylie depicted mid-twentieth-century American women as grasping and physically repulsive.

Wylie was not alone in blaming all manner of social problems on American women. A cadre of emerging Cold War gender experts joined this chorus, proffering research that proved that American women had begun to devolve at the very moment they gained the right to vote in 1920. Wartime independence had only worsened women’s moral decline. Ralph S. Banay, a professor of criminology at Columbia University, former chief psychiatrist at Sing Sing Correctional Facility and a popular anti-communist expert on juvenile delinquency, claimed that crime and juvenile delinquency resulted from the emotional childishness, cruelty, and materialism of women (the racism of the 1965 Moynihan Report criticizing black families also drew rhetorical force from vast reservoirs of Cold War misogyny).36 Using scientific objectivity to mask his misogyny, Banay wrote, “Women’s emotional development lags far behind their social-economic progress.” In Banay’s expert opinion, equality for women could only result in disaster: “The danger is already showing in the aggressive and uncontrolled behaviour of many women—often in outright criminal conduct, for the natural tendency of women toward infractions of law is probably greater than that of men.”37

Anti-communists claiming to speak for all Americans dismissed progressive women who criticized their viewpoints as unnatural and unrepresentative of American womanhood. In 1950, for example, the American Legion published a newsletter, Summary of Trends and Developments Exposing the Communist Conspiracy. This tract declared that only a communist would object to the fact that “a woman worker carrying out the same work as a man” was paid “30 to 40 percent lower wages than the man.” In fact, this kind of criticism, the writer maintained, was “nothing more than another example of the ‘present Communist line.’”38 Readers were left to infer that since communists criticized disparities in pay equity, such disparities were only a problem in the eyes of communists.

For anti-communists, sexism was just plain common sense. They unabashedly expressed their conviction that women were intellectually and politically inferior to men, a core belief that American culture shared with its wartime allies. But the violence of American racism was not as easily dismissed. During the war, civil rights activists had adopted the Double V campaign—signifying victory over the Axis powers, as well as a second victory over racism at home—to amplify the contradictions between a war fought in the name of democracy and domestic practices of violent discrimination. After the war, anti-communists’ continuing expressions of racism evoked comparisons with the white supremacy of Nazism. For European countries coming to terms with the aftermath of the Nazi genocide, American white supremacy was alarmingly familiar.

Anti-communists recognized that American-style white supremacy cast them in a bad global light, even as they continued to believe that it was as natural and just as their misogyny. The FBI and other anti-communists monitored civil rights activities scrupulously but surreptitiously during World War II, increasingly uneasy about what they saw as the propaganda potential of anti-racist activism. The Soviet Union did indeed use American racism to malign capitalism. But anti-communists claimed that charges of racism had no basis in reality at all, but were fabricated by masterful Russian propagandists. They did not consider racism to be “factual information.” Rather, it was their version of “fake news”—a public relations problem to be addressed through relentless attacks on those expressing anti-racist sentiments.

Still, anti-communists subtly adjusted the language they used to talk about race in New York City after the war, betraying their worry about international criticism of American white supremacy. The former FBI agents who founded the American Business Consultants were particularly circumspect around race, as Chapter 3 describes in more detail. They shared the belief that black people were racially inferior, but in order to maintain the illusion of benevolent Cold War consensus, they distanced themselves from racist fellow-travelers like anti-communist Elizabeth Dilling and Mississippi Senator John Rankin, whose bigotry was so overt as to make comparisons with Nazism unavoidable.

In their efforts to make such comparisons less obvious, anti-communists used language in their media campaigns that was less directly racist than that of their predecessors, relying on chains of racist signification rather than fervent avowals of white supremacy. Anti-communists, for example, did not object to violence against African Americans on moral grounds because largely they agreed with the use of violence to maintain the existing racial order. Instead, they objected to racist violence because it could be used by communists to embarrass Americans internationally, encouraging other countries to question and deride American democracy. The FBI’s fear of being embarrassed by progressive women and people of color, as we will see in Chapter 3, was a recurring theme in the secret files they maintained on the Broadcast 41 and other progressives. The authoritarianism of anti-communism was such that they did not like being questioned in the first place. When the questions came from groups of people they considered their inferiors, anti-communist retaliation was swift and vicious.

By surveying the lively and dissenting perspectives on gender, race, and nation that were in the air in 1930s and 1940s New York, and then by detailing the suppression of these ideas and the people who held them, this book pieces together the events that allowed anti-communists to seize the ability to speak for all Americans, reinforce forms of storytelling favorable to white supremacy, and shape the content of televised American entertainment programming that would appear on network television. The events that transpired between 1949 and 1952 offer a textbook example of how political forces used a new medium to impose their viewpoints, in the process supporting conditions that enabled the reproduction of a narrow and restrictive formulation of tradition across decades, to be invoked repeatedly in the service of G-Man masculinity.

❖ ❖ ❖

Vera Caspary in The White Girl, has probed closer to the heart of the almost white Negro than any writer who has thus far attempted to portray the girl who steps over—“passes” in short. She has not allowed herself to be swept into conventional mental attitudes, nor silly sentimentality. There is a delightful absence of “primitive passion,” “back to Africa,” “call of the blood,” “Racial consciousness” “urge for service,” “natural inferiority,” “primitive fear.”

Alice Dunbar Nelson (poet, journalist)39

American culture is fond of the notion of a marketplace of ideas, but less astute when it comes to acknowledging ideas that either were prevented from making it to market in the first place or were set up to fail. Consequently, stories that never made it to market and did not become part of official histories can tell us a great deal about media production and history-making. As the following pages show, the goods that came to market in television were narrowly controlled by anti-communists determined to impose their restrictive perspective. Despite its claims to speak for all Americans, 1950s entertainment programming was told from a very specific perspective, one that shared conservative values concerning race, gender, class, and nation. Both anti-communists and communists shared a masculinist certainty in the rightness of their outlook and the wrongness of those who disagreed. This book argues that in order to evaluate the rightness of a perspective, it is vital to be able to compare and contrast it with many others.

The Broadcast 41 wanted to tell an array of stories, from many different points of view. In contrast to anti-communists’ brutal efforts to quash dissent, the Broadcast 41’s lives and work reflected their investment in the cultural and political importance of diverse perspectives. Although many of the Broadcast 41 did not consider gender to be the defining characteristic of their identities, I describe the Broadcast 41 as women because gender was a characteristic they all shared, in industries and political circles that were dominated by white men. Their professional work took place within the broader confines of being diverse women in professions that were reserved for white men, within industries requiring them to create demeaning and degrading representations of women and people of color. While they understood themselves to be women and progressives, the Broadcast 41 lived the heterogeneity of those categories, reminding us that people always exceed our attempts to herd them into categories.

However inadequately the term “women” captures the range of their perspectives, the Broadcast 41 knew their perspectives conflicted not only with the racism of anti-communists, but with the sexism of progressive white and black men as well. As Michael Denning remarks, “the Popular Front was more prepared for the racial realignments of the war years than for the gender realignments.”40 Consequently, progressive women like the Broadcast 41 fought for equality on multiple fronts: against the misogyny of the postwar era, against white supremacists, against xenophobic isolationism, and often with their own comrades who, like blacklisted actor Zero Mostel, expected their wives “to be home seeing that everything was nice for him, taking care of him and the boys.”41 For black women, these struggles were far more grueling. Years later, singer and actress Lena Horne recalled the strain that racism and sexism put on her first marriage. Black women, she observed, “have to be spiritual sponges, absorbing the racially inflicted hurts of their men,” while at the same time giving them the courage to deal with the “humiliations and discouragements of trying to make it in the white man’s world.” It was not easy, she noted, “to be a sponge and an inspiration.”42

For the Broadcast 41, gender did not exist in isolation from other aspects of their identities. Instead, modifiers crisscrossed the identity of women: they were working-class women, progressive women, black women, immigrant women, Jewish women. Progressive women had few illusions about women as a category, recognizing that their perspectives and the lives they led contradicted those of white conservative women who considered themselves guardians of what the FBI termed domestic security. The Broadcast 41 apprehended the social world in ways that were radically different from those of white conservative women and many men on the left and right, creating media, art, and culture that celebrated change and variety rather than despising those as harbingers of civilization’s moral decline. Because of their capacious understandings of identity, the Broadcast 41’s political and creative work did not reflect a single dimension of their identities as much as it did a belief that perspectives with different vantage points enhanced democracy and freedom. In contrast to anti-communists’ efforts to monopolize the universal—to speak in one voice for all Americans—the Broadcast 41 cherished the notion that in the words of writer, director, and producer Gertrude Berg, gray-listed for her support of blacklisted actor Philip Loeb, “to be different then wasn’t such a sin.”43

The Broadcast 41 knew what it was like to be different. Their lived experiences defied the perspectives on Americanism favored by anti-communists. Because of the Depression, the Broadcast 41 had firsthand experience of economic hardship, understanding the determinative role that economic advantages play in people’s lives. Many of them, like writer Vera Caspary, came from families that had experienced massive reversals of fortune in the 1920s and 1930s. At the same time, black middle-class women like Lena Horne recognized that wealth shifted, but did not eliminate, the oppression they experienced at the hands of white supremacy. Operating within the critical framework of the Popular Front, progressive white women working in broadcasting were more likely to agitate for civil rights and to assert their rights as workers than they were to demand equality for women, because while racial justice was part of the Communist Party’s organizing platform, gender equality was not. Lesbian directors like Margaret Webster likewise remained quiet about the impact of homophobia on their lives in order to survive, but devoted substantial energies to efforts to fight racism in theater.

The lives and work of the Broadcast 41 unfolded against the dynamic backdrop of progressive cultural production in New York City, a place where many of them were born, worked, and died, a city they believed was like no other city in the world. Unlike Paris, London, and Berlin, New York City had emerged from World War II an unrivalled cultural and intellectual center, unscathed by the war’s physical devastation. More international and liberal than any other major American city, the anti-racist politics of the Popular Front flourished in the fertile ground of Harlem. As literary scholar Farah Jasmine Griffin observes of Harlem during World War II, progressive black women in particular “couldn’t wait to return.… Amid the noise, the rush, the thrill, and the trepidation, they came, they settled, they made homes, and they made art.”44 Blacklisted author and New Yorker Dorothy Parker shared a similar sense of the city: “New York is always hopeful. Always it believes that something good is about to come off, and it must hurry to meet it.”45 Actress Judy Holliday said that leaving New York was like “‘losing a leg,’ and returning was finding that, after all, ‘both legs were there and walking around.’”46

The Broadcast 41’s attachment to New York City was especially profound during the second half of the 1940s, when progressives believed that the defeat of fascism in Europe was going to translate into the defeat of racism at home. New York City’s dynamic traffic across theater, music, news, magazines, book publishing, and broadcasting drew actors, musicians, dancers, writers, and likeminded progressives into critical and creative exchanges about U.S. history, politics, and culture. Having fought against fascism, white supremacy, anti-Semitism, and xenophobia in the 1930s and 1940s, progressives working in and around broadcasting anticipated turning their talents and energies to enhancing American democracy.

Progressives in New York City recognized that televised popular culture—from sitcoms to soap operas to prime-time melodramas—was going to play an unprecedented role in disseminating new perspectives to a vastly expanded national audience. The Broadcast 41 were not naïve or uncritically utopian about the limitations of mass media. Many of them had worked in the less restrictive environment of theater and recognized that the economic imperatives of industries like film and radio made challenges to the status quo difficult. But they chose to fight over popular culture, holding fast to the belief that media might yet serve as tools for resistance. With the goal of introducing hitherto suppressed perspectives into popular culture, they produced, created, and performed in narratives that appealed to justice and democracy, agreeing that popular culture could educate people and promote compassion and understanding rather than fear and anger. Against tide and times, the Broadcast 41 appealed to the best in audiences. Anti-communists, as we will see, catered to the worst.

❖ ❖ ❖

The only conspiracy I know about in the entertainment industry is the one of blacklisting by Aware, Inc., Red Channels, and CounterAttack.

Madeline Lee (actress)47

It was known as one of those dangerous shows, because history was dangerous in those days. History is always dangerous.

Abraham Polonsky (writer)48

Throughout much of the twentieth century, critics and scholars dismissed television as a hopelessly lowbrow medium, inferior and common. But the FBI recognized that prime-time entertainment programming was a key battleground in the anti-communist war over American identity. The Bureau and other anti-communists were far less likely than progressives to make aesthetic distinctions between Hollywood and broadcasting, believing that Hollywood films and scripted radio and television programs alike exposed large audiences to dangerously radical social ideas and issues, by which they meant ideas not compatible with their preferred ways of seeing the world.

These concerns caused the FBI to initiate investigations of communist influence in Hollywood before World War II, but the U.S.’s wartime alliance with the Soviet Union stalled right-wing attempts to rid film of progressives. After the war ended, however, anti-communists renewed these efforts, initiating three new investigations into communists in Hollywood in September 1947, April 1951, and September 1951. The first of these investigations bore fruit when members of the group of filmmakers who came to be known as the Hollywood Ten were cited for contempt of Congress in 1947. “The long interval between the first and second investigations,” according to blacklisted writer Albert Maltz, resulted from the fact “that the legal case of the Hollywood Ten was proceeding through the Courts during that time.”49 That legal case concluded in June 1950, when three separate judges sentenced nine of the Ten to pay fines and serve time in prison.

Inspired by their victory over the Hollywood Ten, anti-communists turned their attention to television. The FBI considered broadcast programming threatening enough to require continuous surveillance and intervention. Indeed the Bureau helped produce programs favorable to the FBI’s point of view. Their most successful collaboration was with Phillips H. Lord on the popular reality series Gang Busters (1935–57), which used material drawn from the cold cases of the FBI. Not surprisingly, crime programs like Gang Busters and police procedurals were anti-communists’ preferred form of programming, since these genres affirmed their law and order perspectives and celebrated patriarchal moral values considered to be 100 percent American, a phrase anti-communists shared with the Ku Klux Klan.50

In the late 1940s, a group of former FBI agents and military intelligence officers espousing these law-and-order perspectives led the charge against progressive influence in broadcasting. Financed by an unusual collaboration between Jewish anti-communist importer Alfred Kohlberg and the Catholic Church, these men established the American Business Consultants in 1946 (the definite article emphasizing their sense of self-importance). This organization published the influential anti-communist newsletter CounterAttack (1947–71) and their self-proclaimed bible of the blacklist, Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television (1950).51 The American Business Consultants also inspired imitators who helped spread the gospel of anti-communism, including AWARE, Inc., founded by the author of Red Channels’ “Introduction”, Vincent J. Hartnett, in collaboration with anti-communist supermarket-chain owner Laurence A. Johnson.

The American Business Consultants propagated the idea that communists had infected broadcasting with their subversive virus, with the intent of spreading the disease of dissent to audiences. In his introduction to Red Channels, Harnett wrote, “The Communist-operated escalator system in show business has been in force for at least 12 years—since the Spanish Civil War. Those who are ‘right’ are ‘boosted’ from one job to another, from humble beginnings in Communist-dominated night clubs or small programs that have been ‘colonized,’ to more important programs and finally to stardom.”52 Anti-communists argued that the “so-called ‘intellectual’ classes—members of the arts, the sciences, and the professions” possessed dangerous, un-American ideas and that they must be prevented from access to the airwaves by any means necessary.53 As we will see, FBI files confirm journalist Betty Medsger’s observation that for the Bureau, “to be an intellectual, like being black, was to be regarded as a potential subversive, if not an active one.”54 Progressive intellectuals (including scientists, artists, and educators), in the estimation of anti-communists, were intent on nothing less than the “increasing domination of American broadcasting and television, preparatory to the day when—the Cominform believes—the Communist Party will assume control of this nation as the result of a final upheaval and civil war.”55

With its cultural and intellectual elites, interracial social venues, and more liberal attitudes toward gender and sexualities, New York City loomed large in the anti-communist imagination as an incubator for subversive ideas, organized dissent, and, ultimately, revolution. The only way to stop this New York-based red menace, they argued, was to detect, expose, and prosecute communists and fellow-travelers working in broadcasting.56 To this end, the authors and publishers of Red Channels conducted research to “detect” threats, collaborating with the FBI, the HUAC, and other anti-communist researchers and organizations. They used publications like CounterAttack and Red Channels and a network of gossip columnists that stretched coast to coast to share information about progressives and give anti-communist organizations fodder for letter-writing campaigns and boycotts. Although anti-communists never won the legal victories they hoped for, as the following chapters demonstrate, they successfully tried and convicted those who dared to challenge them in a court of public opinion they had bullied into submission.57

The publication date of Red Channels proved auspicious: the American Business Consultants self-published it on June 22, 1950, just three days before the start of the Korean War. The book’s cover featured a large, masculine red hand dramatically grasping a radio microphone, a metaphor for the impending seizure of radio and television by communists and their fellow-travelers (Figure 1.1). In Red Channels’ “Introduction”, freelance anti-communist writer Vincent J. Hartnett followed J. Edgar Hoover in defining a fellow-traveler as a person who, while not technically a member of the Communist Party, “actively supports (travels with) the Party’s program for a period of time.”58 The expansiveness of this definition, and anti-communists’ liberal application of it, allowed the anti-communist movement to cast a capacious net in their hunt for communist influence.

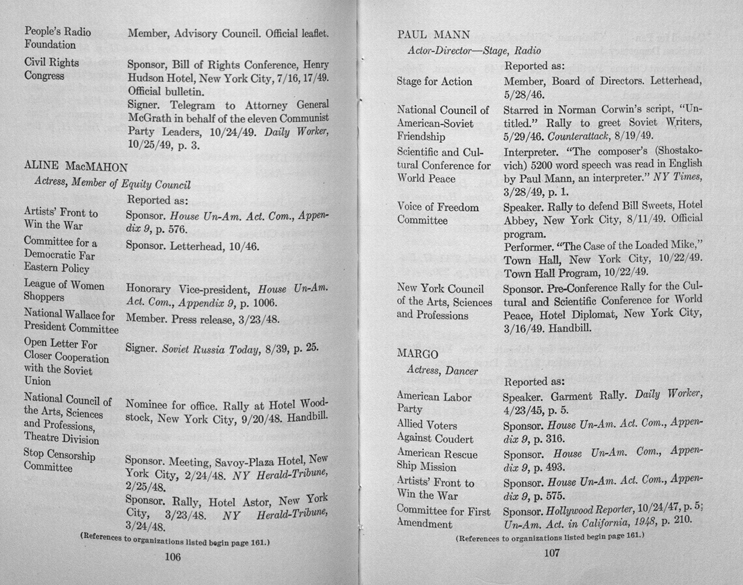

Red Channels’ pages contained an alphabetized list of 151 names, each name accompanied by an inventory of Communist and Communist “front” organizations those listed were alleged to have supported (Figure 1.2). The slender volume served as a crucial weapon in anti-communists’ war on dissent. As early as 1950, social psychologist Marie Jahoda and New York Times journalist Jack Gould recognized that the primary function of the blacklist was, as Medsger later put it, to prevent “people from exercising their right to dissent.”59 In her study of “Anti-Communism and Employment Policies in Radio and Television,” Jahoda found that “‘blacklisting’ procedures are met with fear, frustration, a conviction that innocent people are suspected, constriction and cynicism on the part of talent; an unresolved conflict of conscience on the part of management, with a notion that going along with the temper of the times is required if they are to serve the best interests of their clients.”60 One employee Jahoda interviewed gave the following advice to those working in broadcasting: “Don’t do things that might show you in an unfavorable light. It’s not wise to get involved in politics.”61 Jahoda was herself an example of the price people paid for criticizing anti-communists: she left the U.S. after she was blacklisted for her research on blacklisting.

The culture war anti-communists waged against those identified as subversive and politically impure reverberated across broad swaths of media, encompassing the liberal and literary left (poetry, novels, children’s literature, and non-fiction), news (print and broadcast), and mass-mediated popular culture (animation, film, radio, and comics).62 Conservatives attacked poetry in the 1950s, claiming that experiments with form (and thus challenges to tradition and convention) were a communist plot against American culture.63 Literary scholars have abundantly documented the impact of the Red Scare on African American literature, since anti-communists believed that cultural production on the part of black people could only be the work of outside (read: white) agitators.64 As literary critic William J. Maxwell put it, the FBI waged a “fifty-year crusade to bully and savor African American writing, always presumed to be a type of communist sophistry.”65 The anti-communist crusade, which eventually expanded to include all American popular culture, stifled creativity across media industries, including those from which television might have drawn for inspiration and innovation.

As a consequence of the blacklist, being involved—or having been at some point in the past been involved—in progressive politics could get you fired. Even though actual membership in the Communist Party was in steep decline during the 1950s, anti-communist estimates of the power and reach of the red network were increasing. For all their talk of greedy red hands reaching hungrily for the reins of control over media production, by the early 1950s, anti-communists controlled a far more powerful and influential anti-red network, one that combined the power of the FBI and other government branches and agencies with the reach of veterans’ organizations, private anti-communist organizations, television networks, advertisers, sponsors, and professional snitches. Hoover’s definition of a communist front—“an organization which the communists openly or secretly control”—equally applied to the FBI’s own relationships with the publishers of anti-communist newsletters and books like CounterAttack, Red Channels, AWARE, Inc., and Confidential Notebook, to take just a few examples.66 The authors of Red Channels may have had an acrimonious and paranoid relationship with their former employer, as Chapter 4 documents, but they remained united with the Bureau in efforts to suppress challenges to their authoritarianism.

In an irony not lost on those smeared and vilified by the anti-communist web of paranoia and conspiracy, anti-communists like Hoover and Senator Joseph McCarthy lent urgency to their war on subversion by reference to the vastness of the communist propaganda machine, while at the very same time implementing their own vast propaganda machine. The machine they made, in the words of media critics Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky, allowed them to “mobilize the populace against an enemy” so amorphous that it could be strategically deployed against anyone identified as a “Public Enemy” who threatened the values of the John Birch Society, the FBI, rising politicians like Richard M. Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and others who took up the torch of anti-communists’ political legacies.67 Equating struggles for civil rights and immigrants’ rights with the revolutionary overthrow of the U.S. government, anti-communists declared that challenges to their views resulted from the contaminating influence of the “Comugressive Party,” a portmanteau term frequently used in the pages of CounterAttack.68

While the stated goal of anti-communists was to rid the airwaves of “parlor pinks” (a reference to East Coast intellectuals) and other subversives, the long-term effects of the blacklist proved as significant as the initial purge.69 The blacklist shaped the foundations of the new medium of television, sending a clear message to people working in the industry: avoid anything that could be construed as progressive or risk never working in television again. In this way, anti-communists controlled definitions of America and American values by creating climates hostile to progressive viewpoints in media industries. The elimination of subversives on the basis of presumed political sensibilities and the fear that followed from their removal allowed anti-communist ideas, as Chomsky and Herman observed, to function for decades as powerful mechanisms for imposing conformity.70

Some years later, writer Studs Terkel put his finger on the logic that attributed any criticism of anti-communism to the dire influence of communism. If, he asked an NBC executive, communists are against cancer, does that mean we have to be for it?71 The answer to Terkel’s question was a resounding yes. To extend this logic, if communists were for civil rights, then real Americans had to oppose them. If communists supported state-subsidized child care, then child care must be a communist plot. Thus did the blacklist set well-defined limits for the ideas that could be expressed in television without fear of “controversy” (a code word for subversive content), invoking these limits for years to come in order to govern the content of entertainment programming.

Progressives’ resistance to these postwar retrenchments was formidable and courageous. In the years after the war’s end, progressives promoting the rights of African Americans and immigrants clashed with anti-communists, who wanted to arrogate for themselves the right to speak for a nation that viewed the world from a single perspective, based on homogeneous understandings of god, country, family, gender, race, and class. The Broadcast 41 swam against this rising postwar tide of anti-communist racism, misogyny, and xenophobia. They criticized the discriminatory nature of anti-communist beliefs and fought against these, even as opportunities for dissent began to narrow in the late 1940s, and as a powerful anti-communist backlash against progressivism began to loom on their horizons.

Anti-communists did not single out women specifically for attack, but as this book makes clear, postwar shifts in gender made women attractive targets. Even though media industries were dominated by men in occupations like producing, directing, and writing, a full 30 percent of those personnel Red Channels identified as communists or fellow-travelers were women. The ranks of the blacklisted included actresses like Rose Hobart, Pert Kelton, Gypsy Rose Lee, Madeline Lee, Jean Muir, Fredi Washington, and Minerva Pious who had achieved modest forms of fame; choreographer Helen Tamiris, known for dances celebrating African American culture and protest; musicians and singers like Ray Lev, Lena Horne, and Hazel Scott who fought racism; Mexican-American dancer Margo, an early celebrant of Latinx identity; anti-fascist news commentator Lisa Sergio; progressive writers like Gertrude Berg, Vera Caspary, Ruth Gordon, Shirley Graham, and others listed in this book’s Dramatis Personae. One indication of the blacklist’s success is that where actress Lucille Ball, who survived her own scrape with the blacklist in 1953, remains a household name, very few of these women’s names are remembered today, even by broadcast historians.

❖ ❖ ❖

For a long while, I wouldn’t talk about it at all. I do now, because there’s a whole new generation that doesn’t remember. And the more one knows, the more one can see, and not allow history to repeat itself.

Kim Hunter (actress)72

It was a cloud that never went away. It was terrible. It destroyed a lot of people, more than anybody is ever going to know. It killed them, even when they weren’t dead. It struck fear into the hearts of all kinds of people.

Arthur Miller (playwright)73

Accounts of the blacklist and its impact on American culture remain rare in scholarship and popular culture, while images of the happy days of the 1950s abound. Because our attention has been drawn to the content that viewers ultimately saw on their screens, we have had fewer opportunities to consider who made that content and the circumstances that shaped production. And understandably so: it remains more time-consuming and difficult to document the content that was in the air before the anti-communist purge eclipsed it than content readily available on network and cable television, DVDs, and streaming services. Redirecting attention not to what we have seen on screens, but to what we were prevented from seeing is to tell a very different story about the possibilities of television as a new medium as well as the wide-ranging perspectives of those who had once dreamed of writing stories for it.

Histories are shaped by what appeared in the pages of newspapers and what appeared on screens around the nation. Because what happened during the blacklist era has been so deeply suppressed in popular culture, few histories of television recount the impact of the blacklist on the industry, despite its occurrence at such a formative moment in the new medium’s development. Radio writer, director, producer, and historian Erik Barnouw described the blacklist at length in his history of broadcasting, written while events were still fresh in the minds of progressives, but many later books on television scarcely refer to it.74 Other books have sporadically documented aspects of the blacklist—some of them mentioning its effects on broadcasting.75 Some, like Thomas Doherty’s scholarly Cold War, Cool Medium, have taken a more benign view of Cold War television, arguing that “During the Cold War, through television, America became a more open and tolerant place.”76 The women and men who were driven out of the industry in the early 1950s would have disagreed with this view.

Compounding the initial suppression, journalistic histories of television have been frequently told from the perspectives of cold warriors who approved of the blacklist. Freelance writer David Everitt’s 2007 A Shadow of Red: Communism and the Blacklist in Radio and Television is a case in point. In it, Everitt concedes that anti-communists may have gone too far in violating the constitutional rights of progressives but argues that they were broadly justified by the magnitude of the Communist menace.77

To the extent that the blacklist does come up, it does so in regard to Hollywood and, to a lesser extent, theater. The cinematic example of the Hollywood Ten certainly helped solidify the association of the blacklist with film. Because film has long been considered a more culturally and aesthetically meaningful medium than broadcast media, anti-communist efforts to censor film were taken much more seriously by later generations raised on the belief that American television could never have been more than what it became after the blacklist made controversy (and thus innovation) synonymous with communist influence and un-Americanism.

The elitism that characterized cultural criticism in the 1950s on the right and the left has also contributed to amnesia around the blacklist. Whatever their political beliefs, male intellectuals agreed that television was the opiate of the masses, a medium so lowbrow as to scarcely merit their attention. In contrast, and as Chapter 3 emphasizes, both the Broadcast 41 and anti-communists took forms of storytelling like broadcast entertainment programming, children’s literature, dance, and music—especially as these were transmitted via television—very seriously indeed. Intellectuals from the Cold War onward continued to disparage these modes of storytelling, privileging instead news and political programming, seen as rational spheres of political persuasion and muscular debate. Televised news and political programming, in their estimation, were the places where hearts and minds would be won and lost, not media made for women and children.

Consequently, despite the thousands of passionate fan letters received by programs like The Goldbergs that credited the radio sitcom with combatting intolerance and anti-Semitism, the persuasive dimensions of such programming were dismissed as being nothing more than feminized, mass-produced fantasies. As a result, scholars have painstakingly documented anti-communist and corporate control over news media, paying substantially less critical attention to anti-communist surveillance of, and control over, entertainment programming.78 Not surprisingly, this preoccupation with news media—a segment of the industry that has been especially resistant to incursions by women and people of color—has resulted in a marked lack of attention to the efforts of women and people of color to intervene in broadcast entertainment programming, efforts that had begun to alarm anti-communists as early as the mid-1930s.

Regardless of subsequent recollections, at the end of World War II, progressives and anti-communists recognized that television was poised to affect not only how Americans understood American identity in the 1950s, but how they would remember the past for long decades to come. These were prescient views. Although television itself has long dramatized its own version of its genesis and subsequent role in historical events ranging from the Vietnam War to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, it has had surprisingly little to say about the dramatic series of events that transformed the new medium in the late 1940s and 1950s.79 This silence reflects the medium’s own investment in a consensus version of history. In the industry’s version of television’s history, the medium figures as domestic hearth, a reflection of the hopes and dreams of the Cleavers, the Andersons, and other white middle-class people who conformed to anti-communist understandings of what it meant to be American. The origins of the medium in a war on dissent have been thus obscured; the story of the blacklist hard to tell because it challenges myths about television’s history and its role in American culture.

While television fondly looks back on the images of domestic life it created in the 1950s, the broadcast industry has had little to say about the lively dissent that characterized the late 1940s media industry in New York City and the repressive realities of the blacklist era that followed. Every once in a while, the blacklist has come up, but when it does, it has appeared as a story in which CBS, for example, bravely televised the Army-McCarthy hearings in 1954 and nurtured the liberalism of journalist Edward R. Murrow. Of course, these accounts do not mention that by the end of 1950, CBS had begun enforcing the most stringent loyalty oath program in the industry, creating its own “spook” department to monitor and investigate employees and to ensure compliance with anti-communist definitions of Americanism.80

The memory of the blacklist introduces troubling contradictions into television’s celebrations of the very consensus to which the industry attributed the homogeneity of its pictures of American life. Indeed, according to television history as it was shaped by anti-communism, the images that appeared on television were what postwar Americans demanded of the industry. Rather than affirming the belief that televised entertainment programming grew out of the desires of viewers, the blacklist forces us to acknowledge the repressive measures taken to ensure the dominance of this anti-communist view of America. In place of consensus, the blacklist reminds us that it took loyalty oaths, boycotts, and firings of progressive workers; the chilling of speech; the censorship of appearances by African Americans; and surveillance and retaliation by the FBI to impose these sets of stories on the new medium of television. Absent images of dissent, it was easy to dismiss the bigotry of the 1950s as though it was in fact a consensus of that era—one shared by all people who identified as Americans. Restoring the blacklist to television history shows us consensus was partial at best.

The silence surrounding the blacklist era and the suppression of the perspectives of people like the Broadcast 41 have allowed representations of family, gender, race, and class shaped by anti-communism to serve as sleeper cells, imitated by later television programs, appropriated by politicians to invoke a nostalgic, conservative past, and celebrated by media industries invested in a narrative about a sexist and racist consensus that in turn legitimizes continued industrial practices of stereotyping and exclusion. The resultant amnesia has allowed television to treat its image vaults as historical archives rather than industrial products, as reflections of reality rather than versions of reality shaped by political and economic forces. This book marks an effort to counter what literary critic Mary Helen Washington calls “the amnesia that McCarthyism, the FBI, and the CIA have promoted,” but with regard to control over television and popular culture rather than literature or film.81

Drawing inspiration from the significant body of feminist scholarship exploring the roles that women and people of color have played in literary production and in the making of history, this book restores to view the work that people who would later be described as minorities had been doing across entertainment industries, as well as the role that they were poised to play as this work fed the hungry new medium of television. The forty-one women blacklisted in 1950 were eager to find ways to use the emerging medium to educate Americans and promote civil rights, political and economic justice, and peaceful political struggle. They were at points in their careers where they might have done so. Their accounts of what they had dreamed of creating and what happened to those dreams have long been missing from the history of television.

❖ ❖ ❖

I didn’t set out to make a contribution to interracial understanding. I only tried to depict the life of a family in a background that I knew best.

Gertrude Berg (actress, director, producer, writer)82

Maybe tell how I nearly missed the train in Sault Ste. Marie. Is that what people mean when they say don’t go on the stage, it’ll ruin your health, break your heart, and you’ll wish you were back in Wollaston living a normal life, loved by some good man?

Ruth Gordon (actress and writer)83

Documenting the perspectives of progressives like the Broadcast 41 led me through a maze of sources. Because the women listed in Red Channels had all been born in the first decades of the twentieth century, I was forced to resort to means other than oral history to understand their varied perspectives. Given the vagaries of human memory, reading what the Broadcast 41 had written in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, as events were unfolding, probably offered a more accurate sense of events than what they remembered many decades later, filtered as memories are by time and trauma.