2. Undocumented migrants, healthcare and health

© 2018 Marianne Jossen, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0139.02

In this chapter, I shall provide some contextual information about undocumented migrants in Europe. I discuss concepts of ‘undocumentedness’, and various estimates of the number of undocumented people, as well as outlining healthcare policies and practices across a number of European countries, with a particular focus on Switzerland. I will also address the question of undocumented migrants’ health issues.

Estimates of the uncountable and concepts of the unnamed

Lacking the legal entitlement to stay in a country, undocumented migrants have been described as ‘formally excluded, but physically present within the state’s territory’ (Karlsen 2016:136). The category generally includes those who have overstayed their visas, people who crossed the border without legal entitlement to do so, and failed asylum seekers (Kotsioni 2016).

Undocumented migrants’ names therefore do not appear in official state registers, as their movements across countries are rarely tracked by the authorities and no census reaches them. Furthermore, and as we will see in greater detail below, the multiple and ever-changing categories describing a person’s legal status make it difficult to produce accurate data (see Jandl 2004 for further details). Because of these difficulties, research can produce only rough estimates about the number of undocumented migrants. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimates that in 2010, worldwide, about 10–15% of the estimated 214 million international migrants went undocumented (IOM 2010). The Clandestino Project estimated that in 2008, between 1.9 and 3.8 million undocumented migrants lived in the European Union (at that time comprising twenty-seven countries). This equates to approximately 0.39–0.77% of the total population and 7–13% of the foreign population (Clandestino Project 2009; Vogel et al. 2011). The Clandestino Project provides the highest and lowest estimates for a number of countries, as Figure 1 shows.

Fig. 1 Estimates of undocumented migrants in 2008. Graphic by Marcel Waldvogel based on data from the Clandestino Project (2009) and on a map by Wikimedia-Commons-User Alexrk2, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Europe_blank_laea_location_map.svg

Some updated numbers have become available in the interim (Clandestino Project 2017), pointing to a rise in numbers, as the table below shows.

|

Country |

Estimates in 2008 |

Updated estimates (year of update) |

|

Germany |

178,000–400,000 |

180,000–520,000 (2015) |

|

Greece |

172,000–209,000 |

390,000 (2011) |

|

Spain |

280,000–354,000 |

300,000–390,000 (2009) |

Fig. 2 Latest updates concerning the number of undocumented migrants with comparison to estimates of 2008, according to the Clandestino Project (2017).

Accordingly, the Frontex Annual Risk Analyses show increases in most of the indicators of irregular migration flows in the EU from both 2013‒2014 and 2014‒2015 (Frontex 2015; 2016). The table below shows examples of two of these indicators: refusal of entry to the EU and detected illegal border crossings.

|

Indicator |

2014 |

2015 |

|

Refusal of entry to the EU |

144,887 |

188,495 |

|

Detected illegal border crossings |

282,962 |

1,822,337 |

Fig. 3 Indicators for irregular migration in 2014 and 2015, according to Frontex (2016).

However, the category of illegal border crossings includes not only those who go undocumented, but everyone who asks for asylum. Moreover there were more people who crossed the border and subsequently asked for asylum in 2015 than in the year before. It is therefore difficult to determine the exact increase in undocumented migrants.

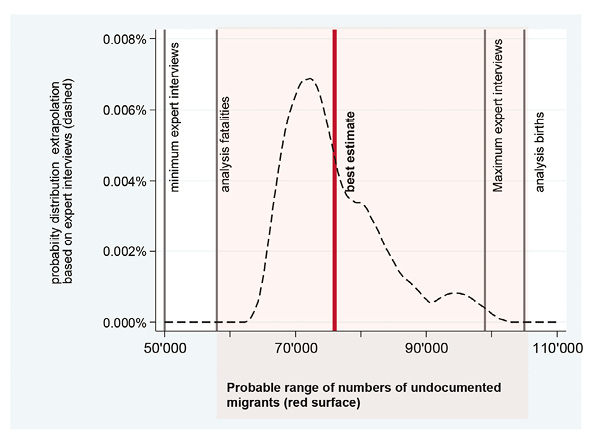

The most recent estimates for Switzerland can be found in a state-commissioned study by Morlok et al. (2015). While an earlier study, also commissioned by the government, estimated a population of 90,000 undocumented migrants in 2005 (Longchamp 2005), Morlok et al. (2015) give a lower estimate of 76,000 undocumented migrants for 2015, a figure based on various sources of information. As Figure 4 shows, the estimate is extrapolated from expert interviews. The experts estimated the number of undocumented migrants to range between 58,000 and 105,000. The number is further contextualised using analyses of the number of known fatalities and births of persons without residency in Switzerland.

Fig. 4 Estimates of undocumented migrants in Switzerland in 2014. Graphic reproduced with permission from Morlok et al. (2015).

Morlok et al. (2015) further estimated that two thirds (63%) of the undocumented migrants entered the country without permission to do so, or overstayed their tourist visa. The final third is made up of individuals who lost their legal right to stay after longer periods of time, for example after a divorce (18%), as well as failed asylum seekers (19%). It is further estimated that about 43% of undocumented migrants in Switzerland were born in South America, while 24% originated in Europe, with a further 19% coming from Africa and 11% from Asia. The majority are between eighteen and forty years old. About 41% have received only a basic education, between six and nine years of primary school. The remaining 59% have received secondary education‒a three to four-year apprenticeship‒or higher education such as a university degree.

This said, it is important to keep in mind that being undocumented is not a personal characteristic but a social construct. In the words of Bloch et al. undocumented migration results from

the interplay between restructured labour markets and increasingly complex migration controls and categories [that] created the interstices within which undocumented migrants found space. (2014:17)

This point can be illustrated with a closer look at Swiss immigration policy. In twentieth-century Switzerland, it is significant that immigration has been framed mostly as a labour issue. For instance, until 2002, the country ran a seasonal workers scheme that allowed foreigners to work in Switzerland for a nine-month period before having to return to their countries of origin for at least four months. Switching places of employment during this nine-month period was forbidden and seasonal workers, also known as saisonniers, had limited access to social security. Only after having worked in Switzerland for four consecutive seasons could a saisonnier obtain a residential permit (Arlettaz 2017). This state of affairs was criticized as inhumane from its inception (Piguet 2013:39). When the scheme was abandoned in 2002 with the introduction of free movement for European citizens, an unknown number of former seasonal workers stayed on and became undocumented migrants. The example of these former saisonniers clearly demonstrates that the status of being an undocumented migrant is a legal construct, and the laws that shape this status can change over time (see also Zimmermann 2011; Castaneda et al. 2015; Karlsen 2016).

It is important to note that being undocumented is a process (see Bloch et al. 2014). This means firstly that a person’s status can shift from legal to undocumented and back again, with accompanying grey areas and transition periods. As a consequence, estimates about the number of undocumented migrants at any given time must always be taken with a pinch of salt.

Secondly, to view someone as undocumented means focusing not only on their legal status but also its effects upon their daily life. Being undocumented is thus never a full description of a person, but rather a social construct.

In this study, the concept of being ‘undocumented’ refers to how people deal with this social construct. The retelling of the undocumented migrants’ stories will both rely on and illuminate the dynamic nature of the migrants’ legal status.

Healthcare for undocumented migrants: policies…

Having introduced definitions and estimates, as well as having explored the shifting state of being undocumented, we will turn to the macro-social forces, namely the policies, that define and shape healthcare for undocumented migrants. As we will see, these policies vary in several ways. This section will give a sense of how such variety comes about‒the result of principles and mechanisms that differ in content, time and space. This discussion will help contextualise the example of Switzerland, which is explored at the end of this section, demonstrating that it is important to discuss policies in relation to local situations.

Healthcare systems are often classified by how they are financed. In Europe, there are two main systems: the Bismarck system, which sets up healthcare via health insurance plans, and the Beveridge system, which is a tax-funded national health service.

How does this affect healthcare policies for undocumented migrants? Fundamentally, tax-based systems ensure that eligibility for care is based on residency. Beyond this, the circumstances in which non-residents are eligible for care must be defined. Within insurance-based systems, the question arises as to who is entitled and/or obliged to take out insurance, and what kind of care those who have not taken out insurance (a category that often includes undocumented migrants) should be afforded.

Björngren Cuadra & Cattacin (2011) classify European countries that follow the Beveridge and Bismarck systems according to the degree of access to healthcare they grant to undocumented migrants. In their classification, a ‘no rights’ policy makes accessing even emergency healthcare impossible. They would also describe as ‘no rights’ policies those in which the attempt to acquire insurance would burden a person with prohibitive debt. A ‘minimum rights’ policy grants access to emergency care. Finally, a ‘more than minimum rights’ approach allows access to both primary and secondary care.

The Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants (PICUM) gives details about the policies that regulate undocumented migrants’ access to healthcare in eleven European countries (PICUM 2007). The authors divide countries into five categories (Figure 5 below), ranging from those where ‘all care is provided only on a payment basis’ (category i), to those toying with the idea of ‘free access to healthcare for all, including undocumented migrants’ (category v). Between the two extremes lie countries proposing free access only in limited cases (category ii), and countries offering somewhat broader coverage (category iii). Furthermore, some countries (category iv), have set up a parallel administrative and payment system specifically for undocumented migrants (PICUM 2007:8).

|

System |

Country |

Classification PICUM (2007) |

Classification Björngren Cuadra & Cattacin (2011) |

|

Tax |

Sweden |

category i |

No rights |

|

Finland |

|||

|

Ireland |

|||

|

Malta |

|||

|

Insurance |

Bulgaria |

No rights |

|

|

Czech Republic |

|||

|

Latvia |

|||

|

Luxembourg |

|||

|

Romania |

|||

|

Tax |

Cyprus |

Minimum rights |

|

|

Denmark |

|||

|

UK |

category iii |

||

|

Insurance |

Lithuania |

Minimum rights |

|

|

Austria |

category i |

||

|

Belgium |

category iv |

||

|

Estonia |

|||

|

Germany |

category ii |

||

|

Greece |

|||

|

Hungary |

category ii |

||

|

Poland |

|||

|

Slovak Republic |

|||

|

Slovenia |

|||

|

Tax |

Italy |

category v |

Rights |

|

Spain |

category v |

||

|

Portugal |

category iii |

||

|

Insurance |

France |

category iv |

Rights |

|

Netherlands |

category iv |

||

|

Switzerland |

Fig. 5 Classification of policies concerning healthcare for undocumented migrants, according to PICUM (2007) and Björngren Cuadra & Cattacin (2011).

As this table shows, there appear to be differences between these two systems of classification; however, these can be explained after a closer look. For example, Austria is placed in the lowest category by PICUM, whereas according to Björngren-Cuadra & Cattacin, they would at least grant emergency care to undocumented migrants. Still, in their more detailed analysis, the latter argue that the situation could also be classified as ‘no rights’ because patients run the risk of accumulating a high debt when seeking healthcare. In the case of Switzerland, the authors mention that the high insurance fees present a significant obstacle for this segment of the population when trying to access healthcare provision.

The classifications provide an insight into the intricate policies that govern healthcare for undocumented migrants and invite us to have a closer look at the variations between them.

To start with, it is important to note that not all countries have specific policies to deal with this issue, despite their having ratified international human rights laws (Biswas et al. 2012). For example, in Denmark ‘policies and legislation on undocumented migrants’ medical rights appear ambiguous and are only sporadically described by decision-making bodies’ (Biswas et al. 2011). It is unclear to what extent healthcare in Denmark must be provided beyond emergency services and whether or not undocumented migrants can be charged for it.

Insofar as policies are formulated, they sometimes only take specific groups of undocumented migrants into account. Thus, in Sweden until 2013, adult undocumented migrants were charged even for emergency healthcare (Verein SansPapiersCare 2016). Meanwhile, children who had not been granted asylum could nonetheless obtain some financial aid (Björngren-Cuadra 2012:115). In Norway, healthcare provision is restricted to emergency-only care for undocumented migrants as well as for short-term working immigrants (Ruud et al. 2015).

In other countries, access is granted to all types of undocumented migrants, but only for specific concerns and/or for a certain period of time. In the UK, undocumented migrants have access to primary and emergency care without charge (Sigona & Hughes 2012:11), while secondary care, involving treatment by specialists or in a hospital, is only delivered upon payment. The Migrant and Visitor Cost Recovery Programme implemented by the UK Government takes further steps to ensure that migrants pay for their own healthcare (Britz & McKee 2015). In Germany, undocumented migrants have access to healthcare during the first forty-eight months of their stay ‘in cases of serious illness or acute pain’ (Björngren-Cuadra 2012:118). Additionally, they have access to perinatal care, vaccinations, and sexual health screenings and care.

Policies and studies on the health and healthcare of undocumented migrants often focus on communicable diseases and reproductive health, which reflects the traditional importance of this area of public health, but which has nonetheless attracted criticism (Bivins 2015). This trend can also be observed in Italy, where from 1996 to 2001 the law gave migrants access to ‘specific services such as pregnancy care, the protection of minors, prophylaxis, and vaccinations’ (Piccoli 2016:15), whilst otherwise remaining ambiguous about the level of healthcare to which they were entitled.

The example of Italy also reveals other elements that have to be taken into account when conducting policy studies: namely changes to policies over time, together with regional differences. Indeed, in 2001, a constitutional reform gave Italian regions exclusive discretion over healthcare. This resulted in a highly fragmented landscape, in which twelve regional governments introduced varying policies ranging from ‘strong activism’ in Tuscany to ‘relative inaction’ in Lombardy (Piccoli 2016:15).

Similarly, in Sweden, a law introduced in 2013 allows treatment of urgent health problems for a nominal fee of five euros. Since then, regional district councils have also been able to grant undocumented migrants the same access to healthcare as citizens (Verein SansPapiersCare 2016). The question of access is thus, once again, regionalized.

Spain provides another very good example of these transformations: in 2012, a widely criticized (Casino 2012; Legido-Quigley 2013) Royal Decree Law revoked the previous right to full healthcare for undocumented migrants, limiting it to some exceptions. Many of the autonomous regions, however

adopted legal, legislative and administrative actions to void or limit [the law’s] effects, while others applied it as intended, resulting in huge differences in healthcare coverage for irregular migrants among Spanish Regions. (Cimas et al. 2016)

In Switzerland, healthcare is generally regulated by the national law on health insurance, the ‘Krankenversicherungsgesetz’ (KVG). Switzerland has a strong federal tradition, so its administrative regions, the cantons, retain much of the power to implement this law and regulate healthcare autonomously in their areas. Furthermore, private companies are heavily involved — generalists’ and specialists’ practices are privately owned and increasing numbers of hospitals also tend to be privatized. The system is thus influenced by both public and private interests (see also Rossini & Legrand-Germanier 2010; De Pietro et al. 2015; Marks-Sultan et al. 2016).

Healthcare is organized via an insurance scheme, participation in which is obligatory for everyone who resides in the country for more than three months. The insurance is provided by private companies, which are legally obliged to use the profits only for the provision of healthcare services to their insured clients. A basic insurance scheme covers primary and secondary care, pre- and post-natal care, reproductive care, psychotherapy — if prescribed by a general practitioner‒preventative healthcare and rehabilitation. Dental care is not covered.

Premiums for these basic insurance schemes differ regionally and depend on the individual insurance policy. Policies that limit the patient’s choice of doctors, for example, are available at reduced prices. Additionally, the insured person has to choose an annual excess ranging from 300 to 2,500 Swiss francs (CHF). A higher excess results in a cheaper premium. On top of this excess the patient must pay out of pocket for 10% of their treatment up to a maximum of CHF 700. Those in reduced financial circumstances can apply for premium subsidies from the state, the amount of which again varies depending on the region (see Chapter Four for a specific example). Those without insurance are still entitled to ‘assistance when in need’ (Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation, Art. 12). Whether this encompasses more than aid in life-threatening situations is subject to debate (Bilger et al. 2011).

According to current policy interpretations, undocumented migrants in Switzerland have both the right and the duty to take out insurance, because they reside in the country (Swiss Civil Code, Art. 23–26; Verordnung über die Krankenversicherung, Art. 1 al. 1; Bundesgesetz über den Allgemeinen Teil des Sozialversicherungsrechts, Art. 13). In 2002, the Federal Social Insurance Office issued an order that threatened sanctions against insurance companies that refused to accept undocumented migrants (Federal Social Insurance Office 2002). These included fines of up to CHF 5,000 and the possibility of legal action in cases of violation of professional discretion. But for undocumented migrants, as for all those who reside in the country, not taking out insurance can result in sanctions as well. As soon as a contract is agreed, a previously uninsured person can be obliged to pay a supplementary penalty fee if they delayed taking out insurance longer than three months after their arrival in the country. In consequence of it being both a duty and right to take out insurance, Rüefli & Hügli propose the following goal:

all undocumented migrants who are legally obliged to have health insurance […] have taken out insurance and have the same access to care providers and medical services, within the scope of basic health provision, as insured people with legal residence. (2011:19)1

Still, this goal is not shared by all political players in the country. In 2016, Ulrich Giezendanner, a member of the right wing Schweizerische Volkspartei (SVP), began a parliamentary initiative asking that undocumented migrants be denied the right to obtain health insurance. The initiative was taken up by the National Council’s Commission for Social Security and Health, and will now be discussed in the National Council on the basis of a vague idea according to which healthcare for undocumented migrants would be provided by a state-financed organization. The Federal Council, on the other hand, recommends the Council reject the motion (SGK 2018).

Policies also vary from canton to canton. Thus, until 2012, it was not clear whether failed asylum seekers had to be granted insurance by the cantons, who are also in charge of the implementation of the laws governing asylum. In addition, a few atypical cantons, like Vaud and Geneva, have adopted policies that allow for the provision of special services to vulnerable populations, which include undocumented migrants. Financing is granted via cantons and municipalities, and the functioning of the services is sustained by tight links between administrations, NGOs and service providers (see Marks-Sultan et al. 2016; Piccoli 2016:17). In the majority of other cantons, including the region on which this study focusses, there are no special arrangements and the national policy is the only one on which service providers and patients can rely.

Detailing the variations between the different policies that regulate healthcare for undocumented migrants demonstrates their differences in content, time and space. Thus, policies shape very specific contexts of care for undocumented migrants in a certain time and place. Local studies, as proposed by this report, can shed light on these contexts.

… and practices

This section will look at how specific healthcare policies shape healthcare practices — meaning the concrete situations of accessing, giving and receiving healthcare — in the case of undocumented migrants. As we will see, restrictive, ambiguous and quickly changing policies cause difficulties in relation to the practical delivery of healthcare, while even in inclusive environments, significant barriers remain. Again, we will turn first to the situation in Europe, and then focus on the Swiss context.

As a result of ambiguous and varying healthcare policies, it can be difficult for undocumented migrants to know what kind of healthcare they are entitled to. For instance, Poduval et al. (2015) analysed patients’ and professionals’ experiences, collected in interviews conducted at a Doctors of the World surgery in London. They report that undocumented migrants are insufficiently aware of their rights. For example, they do not know they are entitled to register with a general practitioner. As a result, undocumented migrants tend to prefer emergency departments. Similarly, Sigona & Hughes (2012:35) state that while most of the undocumented children they studied had a general practitioner, many of the parents did not clearly understand whether or not adults were entitled to the same access.

Lack of knowledge can also be a difficulty for healthcare professionals. In Spain, migrants had difficulties in accessing and obtaining healthcare that were partially due to confusion about regional implementation after the change in the law in 2012, which left healthcare professionals with unclear information about what level of healthcare they were still allowed to deliver to undocumented migrants (Roura et al. 2015). Falla et al. (2016) use the example of treatment for hepatitis B and C to demonstrate the diversity of beliefs among professionals about undocumented migrants’ entitlement to care.

As a result of restrictive policies, healthcare services are underused. Referring patients to hospital is difficult if secondary care is not accessible, especially if it is not easy to decide whether an operation is urgent or not (Sigona & Hughes 2012:39). There is room for alternative strategies, such as ‘borrowing medical cards and resorting to emergency care for non-urgent conditions’ (Roura et al. 2015) but also ‘self-medication and contacting doctors in home countries’ (Biswas et al. 2011).

Undocumented migrants need special knowledge to access some types of healthcare, which is provided by informal networks often organized by NGOs in parallel systems (Huschke 2014). Drawing on the work of Pierre Bourdieu, Huschke shows how social capital is a critical, fragile and transformative factor in this endeavour. Biswas et al. (2011), through interviews with undocumented migrants and emergency room nurses, show that receiving help from Danish citizens proves to be a central strategy when it comes to accessing healthcare. Similarly in Milan, a city in the Lombardy region of Italy where policies are rather restrictive, the time between entering the country and first being seen by a healthcare professional can be reduced by 30% if a person can rely on strong social ties, as a network analysis by Devillanova (2008) shows.

Difficulties in achieving access are also reported in countries where more inclusive policies are in place. Before the national policy changed in Spain in 2012, the migrant population was granted wide-reaching access to healthcare for about three decades. But Vasquez et al. still see ‘inequalities in health among this population which signal social inequalities in access to care’ (2013:237).

Similar problems can be seen in France, despite Laranché’s belief that ‘it could be said to hold one of the most liberal and progressive healthcare systems in the world’ (2012:858). Laranché demonstrates through participant observation that social stigmatization, precarious living conditions and suspicion towards immigrants prevent undocumented migrants from accessing healthcare in France. By drawing on theories influenced by Michel Foucault and Judith Butler, Laranché argues that ‘intangible factors’ affect both undocumented migrants and healthcare providers. Stigmatizing discourse and prejudice shape the views of both sides about what kind of care undocumented migrants deserve.

As a consequence, problems can arise in areas where access is not in question. In the UK for example, even though access is granted for primary care,

in the majority of cases individuals registered very soon after their arrival in the UK and while having some form of residence status. (Sigona & Hughes 2012:35)

Later, patients often travel long distances to visit their general practitioners. Drawing on Laranché, such a situation could be seen as partially the result of discourse and practice, leaving undocumented migrants without the courage to visit a more conveniently located healthcare provider once they have lost their legal status.

In Switzerland, there are about fourteen service providers delivering care to undocumented migrants in the country (Altenburg 2012). Most of the providers are NGOs and charitable institutions (see also Bilger et al. 2011; Weiss 2015). Thus, in a manner similar to other countries, it seems likely that there is a discrepancy between the legal entitlement to insurance with associated care, and the actual delivery of healthcare to undocumented migrants through NGOs and charities. For example, turning their attention to one specific aspect of medical provision, namely pregnancy care and prevention, Wolff & Epiney (2008) show that in Geneva undocumented migrants use such services less than legal residents. For instance, undocumented migrants consulted for an initial pregnancy visit four weeks later than legal residents, and while among the latter only 2% had never had a cervical smear test, this was the case for 18% of the undocumented women.

Reasons for this discrepancy can be found in Bilger et al. (2011) who report healthcare professionals asserting that undocumented migrants lack trust in health service organizations and experience difficulties paying for healthcare and/or insurance. Weidtmann (2015) concentrates on the barriers that hinder people from taking out insurance and interviews two undocumented migrants alongside employees of NGOs and social services. She identifies financial and administrative challenges as the main obstacles. These difficulties are further exacerbated by problems with language, a lack of knowledge about the system, and fear.

In the light of these studies it is not surprising that reviews (Woodward et al. 2013; De Vito et al. 2016) and studies investigating the practices of several European countries (Dauvin 2012) report that even though in many cases legal entitlement may be in place, this does ‘not correspond with access to care’ (Woodward et al. 2013:826). Barriers for undocumented migrants within the healthcare system can be attributed to external resource constraints‒such as lack of transportation or limited healthcare capacity‒or to discrimination and excessive bureaucratic requirements. On the patients’ side, undocumented migrants avoid seeking care because of communication problems, financial restrictions, or out of fear of deportation (Hacker et al. 2015). Access to mental health resources is a particularly critical issue (Strassmayr et al. 2012).

Furthermore, qualitative studies, like those by Poduval et al. (2015), Biswas et al. (2011), Laranché (2012) or Huschke (2014), take into account the views of professionals and patients, and highlight promising ways to further examine healthcare practices in relation to concepts including politics, power, communication and social institutions.

In my third chapter, I shall demonstrate how a local study such as mine can address the need for ‘research which focuses on the treatment of migrants with particular emphasis on the interplay between the various providers of care’ (Achermann 2006:202)2 within Switzerland, whilst simultaneously drawing on the research approach of the above-mentioned qualitative studies, linking healthcare practice to concepts stemming from ethnography and sociology.

Undocumented migrants’ health

Having discussed the ways in which we can understand the policies and practices that shape healthcare for undocumented migrants, the question remains: what kind of health challenges do they face? Recent attempts to shed light on these challenges call into question established ways of thinking about migrants as a homogeneous group of healthy or ill bodies with well-defined characteristics.

One area of migrant healthcare that has traditionally received a great deal of attention concerns communicable diseases and reproductive health. In a colonial and postcolonial context, this research and policy focus often aligns with the idea of migrants as diseased bodies that might bring danger to a ‘native’ population. At the same time, this research tradition shows how Public Health, a discipline that as a whole strongly focuses on communicable diseases, turns its attention also to migrants’ health, and thus to a population that is often overlooked (Bivins 2015). This research emphasis holds true for undocumented migrants in Switzerland: Bodenmann et al. (2009) show that out of 125 screened undocumented migrants, 19.2% had a latent tuberculosis infection. Sebo et al. (2011) and Casillas et al. (2015) examine the sexual and reproductive health behaviour of undocumented women and discover low levels of contraceptive use and correspondingly high rates of unplanned pregnancies.

A second important research focus when it comes to migrants’ health is expressed by the concept of the so-called ‘healthy migrant paradox’ (Domnich 2012). Using this idea, researchers attempt to explain the lower mortality rates among immigrants compared to local populations by asserting that, typically, migration is ‘working migration’ and so only people of generally good health choose to, are chosen to or are able to migrate.

However, there is more to the picture. For instance, a growing body of studies shows that migrants’ health generally deteriorates quickly after their arrival (Gushulak 2007; Woodward et al. 2013), calling into question both the concept of ‘the migrant as a travelling disease’ and the healthy migrant paradox.

Further, an exclusive focus on communicable diseases might overlook other important health issues. For example, an analysis of drug prescription to undocumented migrants by a Milanese NGO shows that non-communicable chronic diseases appear to be prevalent among undocumented migrants (Fiorini et al. 2016). Mental health seems to be particularly affected: subjective perception of health in undocumented migrants is significantly worse than amongst a comparative sample of legal residents (Kuehne et al. 2015). From a medical point of view, another study found that 47.6% of the twenty-one undocumented migrants who were interviewed presented symptoms of anxiety and/or depression (Heeren et al. 2014).

Interestingly, residential status appears to have a causal impact on mental health (Martinez et al. 2015; Heeren et al. 2014; Sigona & Hughes 2012). Furthermore, and perhaps unsurprisingly, there is also a link between barriers to healthcare, constructed through restrictive healthcare policies or practices, and an increased risk to the health of undocumented migrants. A systematic review identified thirty quantitative and qualitative studies and policy analyses drawing links between anti-immigration policies, barriers to healthcare access, and health status (Martinez et al. 2015). For example, a study conducted at a Berlin clinic for undocumented migrants showed that for all of the most common problems — chiefly pregnancy, chronic illness and mental health conditions — patients presented late and with significant complications due to barriers to accessing healthcare (Castaneda 2009).

Sigona & Hughes in turn inform us that The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health in 2007 found that about 20% of deaths directly or indirectly related to pregnancy occurred in women with poor or no antenatal care. The authors propose that

one of the main deterrents to accessing maternity care may be the policy of charging ‘non ordinarily resident’ patients introduced in 2004. (Signoa & Hughes 2012:34)

It is thus not very surprising that Cerri et al. (2017), analysing the prescription of psychiatric medications, found that prescription rates were higher for Italian natives than for undocumented migrants, despite the well-documented phenomenon of mental health issues being more prevalent amongst the latter. Exacerbation of certain health-related problems and underuse of health services go hand in hand.

Thus, the research focus has now shifted from the focus on transmittable diseases and the healthy migrant paradox to the idea that a person’s legal status and the conditions in their country of arrival are a social determinant of their health, a social factor that causally influences health outcomes (Rechel et al. 2013; Castaneda et al. 2015).

The retelling of the undocumented migrants’ stories will draw on these insights by situating them within an analytical framework that allows the careful exploration and retracing of causal links between social institutions, legal arrangements and undocumented migrants’ health.

1 Any quotes from literature not originally in English have been translated by the author and will be given in the original language in the footnotes. Here: ‘Alle versicherungspflichtigen Sans Papiers […] sind krankenversichert und haben denselben Zugang zu denselben Leistungserbringern und Leistungen des medizinischen Grundleistungskatalogs wie versicherte Personen mit legalem Aufenthalt’.

2 ‘Forschung im Bereich Migration, Prekarität und Gesundheit zum Umgang mit betroffenen MigrantInnen, wobei das Zusammenspiel von verschiedenen leistungserbringenden Akteuren besonders beachtet werden sollte’.