’70s-’80s A NEW HOPE?

UNIVERSAL/KOBAL/ART RESOURCE, NY

AN AGE-OLD IMAGE gets an indelible modern update in Steven Spielberg’s transcendent classic, E.T: The Extra-Terrestrial.

In 1977, Apple Computer was incorporated; President Jimmy Carter pardoned Vietnam War draft dodgers; and Elvis Presley died. It was also the year of the cinematic one-two punch of George Lucas’s Star Wars and Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Though these films have often been accused of fueling our current cinematic culture of comic-book franchises, they had more in common with the likes of Apocalypse Now and Easy Rider than many know. (In fact, Lucas had been slated to direct the former, which began as his idea.)

Both blockbusters were profoundly personal and as much a reflection of complex sociopolitical events as their seemingly edgier counterparts. Close Encounters grew out of Spielberg’s desire to make “a movie about UFOs and Watergate.” And Lucas has said that Star Wars “was really about the Vietnam War,” with Richard Nixon inspiring the Evil Emperor. “That was the period where Nixon was trying to run for a [second] term, which got me to thinking historically about how do democracies get turned into dictatorships?” he added. “Because the democracies aren’t overthrown; they’re given away.”

But there was a crucial difference between the Spielberg and Lucas films and Apocalypse Now (not to mention The Conversation and The Deer Hunter): optimism. The original Star Wars “helped close some of the psychological wounds left by the war in Vietnam,” the Washington Post wrote, adding that it reflected “politically uncomplicated yearnings—to be in the right, to fight on the side of justice against tyranny.” It was, in that sense, a warm-up for Ronald Reagan.

But plenty of pessimism remained, and the era was not without its dark dramas, though even Alien and Blade Runner had relatively happy endings (okay, Blade Runner’s was tacked on). During Reagan’s two terms, SF movies reflected a shift “from the social towards a magical resolution of personal problems,” according to Mark Bould in The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction, referring specifically to 1982’s E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial. Like many Disney films—Bambi comes to mind—E.T. is often misperceived as warm and fuzzy, when in fact it takes an unflinching, even harrowing, look at separation, loss, and death.

E.T.’s success led to inevitable knockoffs (think 1988’s execrable Mac and Me) focusing on the cuteness that was all that remained of Spielberg’s film once you subtracted the depth and genius. And even the first-rate films that followed in its shadow relied heavily on gimmicks. One of these was even cited in Reagan’s 1986 state of the union address. “Never has there been a more exciting time to be alive, a time of rousing wonder and heroic achievement,” the President said. “As they said in the film Back to the Future, ‘Where we’re going, we don’t need roads.’”

But American cinema was shifting from movie houses to multiplexes, and you need parking lots for that. Though rogue, under-the-radar works like 1985’s Brazil and 1984’s low-budget first Terminator kept the dream alive, increasing corporatization, an emphasis on merchandising, and the need for cross-cultural global appeal inevitably turned Hollywood into a place where “risky” projects akin to Star Wars and Close Encounters would probably never achieve liftoff.

LARRY BURROWS/LIFE/THE PICTURE COLLECTION

In Operation Pegasus, American soldiers work with South Vietnamese forces during the Battle of Khe Sanh in 1968. Though the Vietnam War led to pervasive domestic disillusionment, it fueled such artistic triumphs as 1977’s Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

1977 STAR WARS

JOHN JAY/© 20TH CENTURY FOX, COURTESY PHOTOFEST

STAR WARS’ triple threat: Mark Hamill, Carrie Fisher, and Harrison Ford blast their way to stardom.

The galvanic popularity of George Lucas’s interstellar barn burner has been decried as the catalyst that opened the doors to decades’ worth of crass, merchandise-driven filmmaking. But its success was anything but certain at the time. In the early ’70s, when Lucas first jotted down ideas for a swashbuckling space epic, science fiction was a largely tired cinematic genre. (Anyone remember 1972’s mutant-rabbit movie, Night of the Lepus?) Even in the wake of Lucas’s 1973 hit, American Graffiti, 20th Century Fox, the studio that green-lit Star Wars, was nervous about the film. Had it not been for Alan Ladd Jr., the executive who alone believed in the project, it may never have seen the light of hyperspace.

The story of Luke Skywalker’s transformation from lowly farm boy to intergalactic hero was not just genre filmmaking. It was, instead, a seamless distillation of decades’ worth of American popular culture tinged with classic myth and stoner mysticism. To the comic-strip gee-whizzery of the old Flash Gordon serials, the densely imagined world of Frank Herbert’s novel Dune, and the pulp space operas of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Lucas added the religio-magic of Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, the hero’s journey of Joseph Campbell, the peyote-fueled pop philosophy of Carlos Castaneda, ’50s car culture, and the Hanoi hangover of Vietnam. In the process, Lucas transformed familiar genre elements into something more profound, while retaining what he called “effervescent giddiness.”

“The amazing thing about the first Star Wars film for a person of my age seeing it for the first time,” the seventy-something novelist John Crowley, three-time winner of the World Fantasy Award, tells LIFE, “was that someone had gone and spent umpteen millions of dollars lovingly and faithfully putting on screen the science fiction of my youth—from the opening title taken from a Flash Gordon–style Saturday serial to a bar just like the bars that pulp writers employed not only in SF but mystery and cowboy tales as well. It was impossible not to laugh with delight at every corny labor-of-love moment. I don’t think young people now get this dimension.”

Though the first sequel, 1980’s The Empire Strikes Back, notably brought a darker vision to the series, the subsequent prequels were mostly seen as disappointments, the emphasis placed on special effects instead of story. “Once you had digital, there was no end to what you could do,” Lucas once said. But he seemed to lose himself in technological innovations even as he transformed the industry through his company, Industrial Light & Magic.

The tepid films didn’t stop legions of rabid fans from packing multiplexes from here to Tatooine. And this year, Star Wars: The Force Awakens became the highest-grossing film ever domestically. It was also widely seen as a return to form, though Lucas himself dismissed it as “retro” and jokingly compared the Walt Disney Company, which now owns the franchise, to “white slavers.” (He later apologized.) But given the fact that he sold his brainchild for $4 billion, it’s clear that he’s complaining all the way to the terrestrial bank.

© LUCASFILM, LTD./20TH CENTURY FOX, COURTESY PHOTOFEST

DIRECTOR IRVIN KERSHNER gives Anthony Daniels (C-3PO) pointers on the set of The Empire Strikes Back. When the film’s first writer, SF legend Leigh Brackett, died, Lawrence Kasdan took over. “It’s a matter of pride for me that I share credit with her,” Kasdan tells LIFE.

© LUCASFILM LTD./EVERETT

Darth Vader (embodied by David Prowse, voiced by James Earl Jones) surveys his deadly domain in the first Star Wars.

LUCASFILM/20TH CENTURY FOX/KOBAL/ART RESOURCE, NY

In The Empire Strikes Back, Luke Skywalker (Hamill) trains as a Jedi Knight on the planet Dagobah with Yoda, a character inspired in part by Albert Einstein and voiced by Frank Oz (whose other voices included Miss Piggy).

© WALT DISNEY STUDIOS MOTION PICTURES, COURTESY PHOTOFEST

IN J.J. ABRAMS’S 2015 Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Rey (Daisy Ridley) crouches with the droid BB-8 during the battle on Takodana. “I remember J.J. saying, ‘He’s not a child,’” Ridley has said of her tendency to use baby talk while acting with her mechanical costar. “He’s a droid with a mission.”

1977 CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND

MARY EVANS/COLUMBIA PICTURES/EMI FILMS/RONALD GRANT/EVERETT

THE MOTHERSHIP lands at Devils Tower at the denouement of Close Encounters. The film fell behind schedule because director Steven Spielberg was constantly coming up with new ideas—partly from the dozens of movies he watched during the shoot.

A postwar craze that would disappear as quickly as the Hula-Hoop” is how astronomer J. Allen Hynek characterized the boom in UFO sightings that began in 1947. But over time, the would-be skeptic acknowledged that many spacecraft sightings are not easily explained—and in 1972’s The UFO Experience, he even outlined a system to classify human interactions with interplanetary beings.

He called them “Close Encounters.”

Hynek’s work was a major influence on a talented young director who had virtually invented the movie blockbuster with 1975’s Jaws. In the wake of that success, Steven Spielberg embarked on a film about an extraterrestrial visitation that leads to an ordinary man’s spiritual apotheosis. “I always . . . believed that there was some truth to it all,” Spielberg has said. “There were just too many similarities in the accounting of UFO sightings.”

Even before Jaws, Spielberg had talked of making “a movie about UFOs and Watergate,” which hardly sounds like a recipe for a hit. In fact, “Close Encounters was the most intimate, personal big-budget movie ever made in its time,” frequent Spielberg collaborator David Koepp tells LIFE. “It was anything but a sure bet. Yes, Spielberg was coming off of Jaws, but just before that he’d made Sugarland Express, which was not commercially successful, and both those movies had gone well over budget. He was considered a risk, and the fact that he was making his passion project made Columbia Studios nervous as hell.”

The film was, of course, a triumph, the result of the fact that “the story was so personal,” Koepp continues. “But because it was so specific, it was wildly relatable. And because Steven treated science fiction with the A-plus tools and collaborators he had available to him, he dignified the genre much the way Robert Wise had with The Day The Earth Stood Still in 1951.”

Though Close Encounters was unfairly compared at the time to the recently released Star Wars, other comparisons were more apt. “How do you like your film?” Steven Spielberg asked the seminal SF writer Ray Bradbury after it premiered, adding, “Close Encounters wouldn’t have been born if I hadn’t seen It Came from Outer Space six times when I was a kid.”

Like Spielberg, Bradbury often used the mundane as a backdrop for otherworldly elements, often adding a nostalgic, melancholy, poetic quality. And his humanistic approach is apparent in It Came from Outer Space’s aliens, which—like Close Encounters’—are sympathetic. “I wanted to treat the invaders as beings who were not dangerous,” Bradbury said, “and that was very unusual.”

As for how he liked “his” film, Bradbury called Close Encounters “The most important film of our time . . . For this is a religious film, in all the great good senses, the right senses, of that much-battered word . . . because for the first time someone has treated all of us as if we really did belong to one race.”

EVERETT

FAMILY MAN Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss) discovers that his strange obsession with building a mountain in his home has a source, when he sees a television news story involving Wyoming’s Devils Tower. The writer-director Paul Schrader (Taxi Driver) had written an early draft of the script, giving the story a distinctly religious tone. But Schrader wanted to focus on an exceptional hero, while Spielberg wanted what Schrader dismissively called “a guy who eats at McDonald’s.” Later, Spielberg called Schrader’s script “one of the most embarrassing screenplays ever professionally turned in to a major studio or director.”

EVERETT

NEARY MAKES CONTACT with extraterrestrials in the film’s culmination.

1979 ALIEN

BOB PENN/© 20TH CENTURY FOX, COURTESY PHOTOFEST

RIPLEY (Sigourney Weaver), warrant officer on the spacecraft Nostromo, wages war against the hostile alien. The inventive film seemed fresh when it was first released, but in fact it was largely inspired by pulp horror.

Is it horror or science fiction? When it comes to the many works that straddle the two genres, the question has been endlessly debated. (Is The Thing from Another World horror or SF? And what about Invasion of the Body Snatchers?) The blurring of the boundaries is particularly apparent in Alien, a slick creature feature about the crew of a space freighter who stumble on an ancient race of aliens. Indeed, the film bears more than a little similarity to the works of pioneering horror writer H.P. Lovecraft, who was, in turn, a proto–science fiction writer. (Confused yet?)

Though he remained largely unknown in his lifetime, Lovecraft was recognized as a titan of the genre after dying in poverty at 46, his legacy becoming “an incalculable influence on succeeding generations of writers of horror fiction,” according to noted author Joyce Carol Oates. But let’s not forget the filmmakers. Writer-director Guillermo del Toro, who himself mixes genres with gleeful abandon, has made the connection between Alien and the Lovecraft novella At the Mountains of Madness, about the discovery of ancient astronauts in the arctic. (The first draft of the film’s script featured such distinctively archaic Lovecraftian words as squamous. Hemingway he was not.)

Lovecraft’s influence can also be seen in the distinctive biomechanical look of Alien’s titular creature. It was designed by Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger, who called a collection of his paintings Necronomicon, after a forbidden ancient book featured in Lovecraft’s writings. The result: “Giger’s designs were an especially unique experience for the audience,” said Alien’s director, Sir Ridley Scott, who also helmed Blade Runner and The Martian, both featured in these pages. “The world had simply never seen anything like that before. His work contributed significantly to the commercial success of the film.”

Like many movies of this era, Alien gives hoary genre clichés a stylish modern spin, bringing a dark, moody vibe to what might have been a programmatic pulp rehash. (“It made living on a spaceship for long periods of time look as grungy and realistic as it probably would be,” the noted SF editor Ellen Datlow tells LIFE.) The result: a massive summer hit that spawned (an appropriate word) a series of sequels—from the sublime (James Cameron’s 1986 Aliens) to the ridiculous (2004’s Alien vs. Predator, which itself led to sequels, video games, and theme park attractions).

Turns out that the Aliens are indeed among us.

20TH CENTURY FOX/RONALD GRANT ARCHIVE/MARY EVANS/EVERETT

The alien vanquished? Not as long as sequels are an option.

© 20TH CENTURY FOX/EVERETT

KANE (John Hurt) investigates one of the mysterious eggs found inside a derelict spacecraft. From inside, a crablike creature attacks him, laying eggs in his chest—a process inspired by certain wasps that do the same thing to beetles and caterpillars.

© 20TH CENTURY FOX, COURTESY PHOTOFEST

Brett (Harry Dean Stanton)—frozen in terror as he faces the alien—breathes his last.

1982 BLADE RUNNER

MPTVIMAGES

RICK DECKARD (Harrison Ford) in hot pursuit of Replicants in a future Los Angeles that clearly bears no resemblance to the sunny contemporary City of Angels. Ford is slated to star in the upcoming sequel, along with Ryan Gosling, Ana de Armas, and Robin Wright.

In 2019, a gang of human-like androids known as Replicants mutiny on a space colony and travel to a decaying Los Angeles, where they are pursued by Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), a bounty-hunting cop known as a Blade Runner. That’s the premise of this 1982 Ridley Scott film, which turned pioneering science fiction writer Philip K. Dick’s typically mind-bending 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? into a futuristic noir. (Scott also directed Alien and The Martian.)

A box office disappointment on its initial release, Blade Runner was criticized for its tacked-on happy ending and extraneous voice-over narration, which was added because studio executives thought the film was confusing—and worse. (Some typical reactions: “This movie gets worse [at] every screening.” “Deadly dull.”) In 1992, the release of the director’s cut put the film’s emphasis back where it belonged: on the visuals. “Blade Runner works almost nonverbally,” SF editor Ellen Datlow tells LIFE. “I think it’s one of the best science fiction movies of all time. It does what SF does best: shows a believable, albeit in this case dystopian, future.”

Like H.P. Lovecraft, the prolific Dick struggled throughout his life as a pulp writer—even trying to break into the mainstream with “literary” novels—before being acknowledged as a protean cultural influence after his death. He also wrestled with drug addiction and mental illness, both of which he channeled into labyrinthine works of art like Valis and A Scanner Darkly. But unlike Lovecraft, Dick received a brief glimpse of the success that was to come. Though he initially balked at Blade Runner, he changed his mind seeing samples of the immersive world the filmmakers had created. “The impact of Blade Runner is simply going to be overwhelming,” he wrote. “It is my own interior world . . . They caught it perfectly.”

But on March 2, 1982, the visionary writer died in Santa Ana, California—three months before Blade Runner’s release opened the door to further Dick adaptations such as Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report and Paul Verhoeven’s Total Recall. (Earlier this year, a Blade Runner sequel was announced, involving both Ford and Scott.) “Dick’s work always asks: What’s human, and what’s not?” Tim Powers, author of On Stranger Tides and other novels, tells LIFE. “And can you ever really be sure?”

© WARNER BROS./EVERETT

HARRISON FORD (left) confers with director Ridley Scott on the Blade Runner set. Believe it or not, Ford’s role was originally offered to Dustin Hoffman, who said, “Why the hell do you want me to play this macho character?”

1982 E.T.: THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL

© UNIVERSAL PICTURES, COURTESY PHOTOFEST

NO ONE who saw this scene when E.T. was first released will ever forget it: E.T. and company prepare for liftoff.

On the evening of August 21, 1955, a flying saucer reportedly landed near rural Hopkinsville, Kentucky. Over the next few hours, the putative UFO’s occupants—“12 to 15 little men,” with “huge eyes” and “hands out of proportion to their small bodies,” according to the local paper—attacked families in an isolated farmhouse.

Known as the Hopkinsville Goblins Case, the encounter became the source material for Night Skies, a horror movie that director Steven Spielberg planned as a follow-up to his 1977 hit, Close Encounters. But while filming Raiders of the Lost Ark, he began having second thoughts.

“Throughout [the production of] Raiders, I was in between killing Nazis and blowing up flying wings,” he said, according to The Films of Steven Spielberg. “I was . . . scratching my head and saying, ‘I’ve got to get back to the tranquility, or at least the spirituality, of Close Encounters.’”

Taking an element of Night Skies’ script (the relationship between an alien and a small boy), Spielberg and screenwriter Melissa Mathison (then Harrison Ford’s girlfriend) came up with E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial. A slam-dunk, right? Not exactly. Columbia (the studio that Spielberg’s Close Encounters had saved) rejected the idea, calling it a “wimpy Walt Disney movie.”

Famous last words. In 1982, E.T.—the story of a lost alien and the boy who befriends him—became what was then the highest-grossing movie of all time and a classic that took its place alongside such “wimpy” fare as Peter Pan, Bambi, and Mary Poppins—not to mention the likes of The Wizard of Oz. It was called “the best Disney movie Disney never made.”

“Steven Spielberg is the least cynical filmmaker I’ve ever met,” frequent collaborator David Koepp tells LIFE. “His connection with the audience is pure because he is the audience. I don’t think he has ever once considered a single decision on one of his movies without picturing himself in a seat in the theatre—not consciously, just intuitively, and in a split second.”

For many, E.T. remains Spielberg’s masterpiece. It is certainly his most personal film, reflecting the alienation he felt as a child of divorce. But like Jaws in 1975 and Star Wars in 1977, E.T. changed the movie landscape forever. Fueling audience desire for escape and heart, it doomed a blackly brilliant movie like John Carpenter’s The Thing, released the same year, and spawned a brood of forgettable knock-offs (including TV’s laughable, but not actually funny, Alf).

Night Skies never saw the light of (ahem) day. But the Hopkinsville Goblins Case was reflected in M. Night Shyamalan’s 2002 hit, Signs.

© UNIVERSAL PICTURES, COURTESY PHOTOFEST

ITALIAN SPECIAL-EFFECTS artist Carlo Rambaldi and his beloved creation, made for a million dollars and fueled by pre-CGI hydraulics. Though he got his start in low-budget Italian slasher films like A Bay of Blood, Rambaldi ended up working on Close Encounters and Alien and winning three Academy Awards.

TERRY CHOSTNER/BRUCE MCBROOM/© UNIVERSAL PICTURES, COURTESY PHOTOFEST

GERTIE (Drew Barrymore) says goodbye to E.T. in the film’s wrenching, beautiful conclusion.

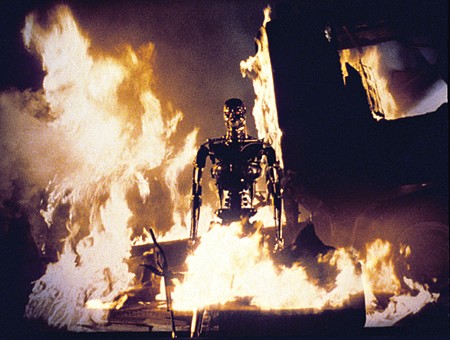

1984 THE TERMINATOR

© ORION PICTURES CORPORATION/EVERETT

THE TERMINATOR emerges from flames, and is a bit worse for wear.

In 1982, 27-year-old schlock movie director and former truck driver James Cameron was in Rome to see a rough cut of his film Piranha II: The Spawning. Sick from stress, Cameron had a fever dream in which a chrome torso rose from an explosion and dragged itself along the floor with kitchen knives. When the ailing young man woke up, he started sketching the vision, which ultimately became the source of his breakthrough film, The Terminator.

Starting in 2029, the movie depicts a world dominated by machines that are systematically wiping out humanity. Threatened by resistance fighter John Connor, the machines send an assassin known as a Terminator back in time to 1984 to murder Connor’s mother, a diner waitress, insuring that John will never be born. Connor, in turn, sends his own emissary into the past—to destroy the Terminator.

Cameron sold his script for one dollar on the condition that he be allowed to direct the film. It was a tall order for an unproven talent, but Cameron pulled it off—not, it should be noted, without skepticism. Reigning stars Mel Gibson and Sylvester Stallone turned the Terminator role down. One candidate, O.J. Simpson, was rejected because Cameron didn’t think he would be believable as a killer. (“He was this likable, goofy, kind of innocent guy,” Cameron has said. “Plus, frankly, I wasn’t interested in an African-American man chasing around a white girl with a knife.”) Though the director was initially opposed to casting Arnold Schwarzenegger, he changed his mind after meeting the muscle-bound star, then best known for middling work in the likes of Conan the Barbarian.

The casting turned out to be inspired. Though Schwarzenegger had only 17 lines in the film, “somehow, even his accent worked,” Cameron has said. “It had a strange synthesized quality, like they hadn’t gotten the voice thing quite worked out.”

Like many involved in the project, Schwarzenegger initially underestimated the director. But Cameron’s pacing and verve made a plot that might have been silly both believable and powerful. The film was an unexpected hit, helping to turn the director from a B-movie failure into the visionary behind such massive hits as Titanic and Avatar. He even wrote and directed 1986’s Aliens, the successful sequel to Alien —and oversaw the first of four Terminator sequels to date.

In 1995, 11 years after Arnold Schwarzenegger’s “I’ll be back” became one of cinema’s most memorable catchphrases, O.J. Simpson—on trial in Los Angeles—was once again found unconvincing as a murderer.

© HEMDALE, COURTESY PHOTOFEST

Arnold Schwarzenegger was originally interested in the role of the hero, but director James Cameron had different ideas. “I was looking at him and thinking he could make a pretty good Terminator,” Cameron said of the former bodybuilder. “He’s like a bulldozer.”

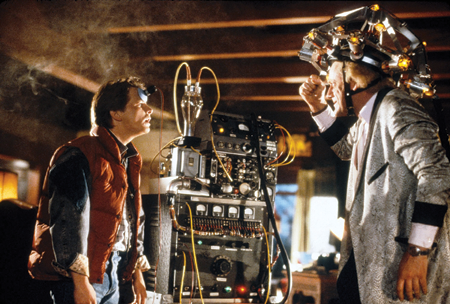

1985 BACK TO THE FUTURE

RALPH NELSON, JR./© UNIVERSAL PICTURES, COURTESY PHOTOFEST

CHRISTOPHER LLOYD, as Doc Brown, proves that timing is everything

From Woody Allen’s 1973 Sleeper to 1997’s Men in Black and 2011’s Attack the Block, the marriage of science fiction with comedy has a rich tradition. That joining of genres has never played better than in 1985’s Back to the Future, directed and co-written by Robert Zemeckis. “It’s just one of the most entertaining films ever made,” David Koepp, the screenwriter and director behind such works as the last Indiana Jones film, tells LIFE. “And the engine of its genius is the perfection of its story.”

The giddy romp tracks the adventures of Marty McFly, who, after mistakenly being sent back three decades in time, needs to ensure his future existence by making sure his parents meet and fall in love. But there’s one significant problem: His mother develops a crush on him. The film is simultaneously mainstream and sophisticated, brash and sweet, naive and knowing—all embodied in Michael J. Fox’s breakthrough lead performance. (He replaced the reportedly humor-deficient Eric Stoltz a month and a half into filming.)

Back to the Future’s overwhelming success fueled two sequels—neither as thoughtful or intricate as the first, of course. Other SF-comedy hybrids followed—including 1987’s parodic Spaceballs, 1997’s Men in Black, and 2005’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. But the first Back to the Future has never been equaled and continues to resonate with audiences “because of the element of wish fulfillment at its heart,” Dean Cundey, the film’s director of photography, has said. “We’ve all said to ourselves . . . ‘If only I could do that all over again.’”

AMBLIN ENTERTAINMENT/UNIVERSAL PICTURES/RONALD GRANT ARCHIVE/MARY EVANS/EVERETT

Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox) and Doc Brown hatch a plan. “This film is the most perfect pop culture example of a satisfying three-act structure I’ve ever seen,” David Koepp tells LIFE.