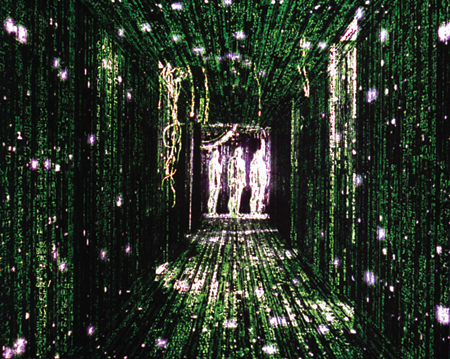

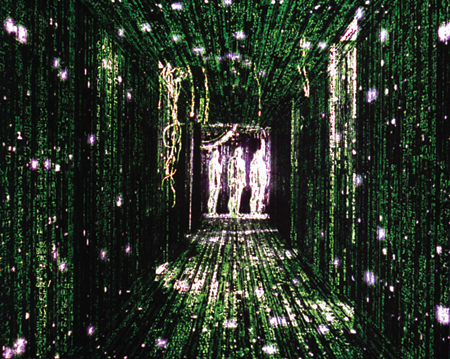

’90s-’10s REEL TO REALITY

© WARNER BROS., COURTESY PHOTOFEST

THE “REALITY” of the Matrix is revealed as an illusion at the close of the 1999 film.

A century before Apollo 11 landed on the moon in 1969, the novelist Jules Verne was writing about space flights, and his fellow visionary H.G. Wells was predicting the likes of suburbs, economic globalization, and the atomic bomb. The author of The War of the Worlds even anticipated the building blocks of Nazi Germany: “The order, the planning, the State encouragement of science, the steel, the concrete, the aeroplanes are all there,” wrote George Orwell, who himself, of course, foresaw government surveillance in his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.

But it took decades for these auguries to become realities. Nowadays, life—and science—move a lot faster. Only 15 or so years after The Matrix, Marriott hotels are offering virtual-reality honeymoons (room service not included), and the Sacramento Kings basketball franchise uses similar technology to give potential ticket-holders a courtside-seat experience. Fourteen years after Minority Report, we have facial-recognition software and gesture-based user interfaces (i.e., you just swipe your hand). In 2008, Wall-E anticipated the climate-change debate, and 2015’s The Martian . . . well, no human has landed on Mars yet, but NASA is currently shooting for the 2030s.

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” the noted SF writer Arthur C. Clarke once commented—and for those of us who grew up before computers, calculators, and Xerox machines, this Brave New World is magical indeed.

It’s also, at times, terrifying. The fearful fruits of Jurassic Park’s genetic-engineering disaster are fictional, of course. But this past December, scientists descended on Washington, D.C., to discuss, among other things, the ethics behind a gene-editing technique called CRISPR/Cas9, which makes it easier than ever to tinker with DNA. The technology could eventually eliminate malaria, improve crops, and even turn pigs into organ donors for humans. But one of the scientists who developed CRISPR/Cas9 had a nightmare in which Adolf Hitler said, “I want to understand the uses and implications of this amazing technology.”

Though immersive virtual-reality technology is now most obviously used in video games and 3-D IMAX movies, a computer application that supposedly helps generate empathy by allowing people to switch genders is in the works, as is—not surprising—a robot sex app. Still, we’re already living in a world in which smart phones and Internet access fuel the impatience, narcissism, and distraction that make up the so-called e-personality, according to Dr. Elias Aboujaoude, Stanford psychiatrist and author of Virtually You: The Dangerous Powers of the E-Personality. “We may stop ‘needing’ or craving real social interactions because they may become foreign to us,” he has said. “We are so immersed in virtual life and have been for some time.”

Even as the line between reality and science fiction continues to blur, the value of what Verne and Wells started a century and a half ago remains clear. “The variety of worlds science fiction accustoms us to, through imagination, is training for thinking about the actual changes—sometimes catastrophic, often confusing—that the real world funnels at us year after year,” SF writer Samuel R. Delany once said. “It helps us avoid feeling quite so gob-smacked.”

DONALD BOWERS/GETTY

A VIRTUAL-REALITY e-screening of Cold Lairs, Disney’s 360-degree teaser for The Jungle Book was held this past April at Samsung 837, a “living lab and digital playground” open to the public in New York City.

1993 JURASSIC PARK

© UNIVERSAL PICTURES/EVERETT

TIM MURPHY (Joseph Mazzello) narrowly escapes becoming the velociraptors’ midnight snack in one of Jurassic Park’s scariest scenes.

In a career that spanned the better part of four decades, the bestselling novelist Michael Crichton wrote about epidemics from outer space (The Andromeda Strain), sexual harassment and computers (Disclosure), and aviation accidents (Airframe). But nothing the Harvard med school grad did would ever be as popular as his magnum opus, 1990’s Jurassic Park, which was made into a blockbuster 1993 film by Steven Spielberg.

Both novel and film tell the story of billionaire mogul John Hammond, who uses genetically engineered dinosaur DNA from insects trapped in amber to create an amusement park filled with real dinosaurs on a fictitious Central American island. But when an employee’s attempted theft triggers a power malfunction, it all goes spectacularly wrong. “Crichton’s central idea was so good, it made whatever we did possible,” David Koepp, who co-wrote the screenplay, tells LIFE. “The idea was just . . . ideal. You understood it quickly, and you believed it immediately. You wanted to believe it.”

Not surprising, the film was accompanied by an avalanche of merchandising. In it, Jeff Goldblum’s character castigates Richard Attenborough’s Hammond for his commercialism, saying, “You stood on the shoulders of geniuses . . . Before you even knew what you had, you patented it and packaged it and slapped it on a plastic lunch box.”

But Spielberg and company did not stop there. In addition to lunch boxes, there were Super Nintendo video games, Lego play sets, sleeping bags, shoes, ties, and Burger King watches. In fact, the Jurassic Park phenomenon is something of a pop culture hall of mirrors: A novel about a theme park disaster becomes a movie about a theme park disaster, which in turn becomes a theme park “disaster” attraction at Universal Orlando Resort.

The novel’s sequel, 1995’s The Lost World, was also made into a Koepp-scripted Spielberg film. (The title pays homage to the 1912 book of the same name by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle—arguably one of the first SF novels ever written.) And the franchise is still going strong. When the third sequel, last year’s Jurassic World, opened, it scored at the time the highest weekend global box office in history.

Can dinosaurs ever be cloned? No: None of their DNA is left on the planet, scientists say. But in 2014, a researcher at Johns Hopkins University synthesized a yeast chromosome. Could next year’s blockbuster be Jurassic Bakery?

AMBLIN ENTERTAINMENT/LEGENDARY PICTURES/UNIVERSAL PICTURES/KOBAL/ART RESOURCE, NY

YOU’D THINK they would have learned their lesson by now, but, no—they keep trying to open an amusement park filled with genetically engineered dinosaurs, to predictable (if thrilling) results. Here, 2015’s Jurassic World is the latest outing in the successful franchise.

1999 THE MATRIX

© WARNER BROS., COURTESY PHOTOFEST

NEO, A.K.A. “THE ONE” (Keanu Reeves), is saved from drowning in sewer muck as a cable lifts him into the belly of a hovercraft.

Take one part Hong Kong martial arts epic, one part dystopian science fiction film, one part Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and throw in a little postmodern French cultural-critical theory in the form of Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation, and you have a recipe for . . . a serious Hollywood hit?

An unlikely scenario, to say the least, but when The Matrix opened at the close of the last millennium, it captivated audiences with its cyberpunk-inflected tale of Neo, a computer programmer who learns that “reality” is, in fact, an elaborate construct generated by sentient machines. The goal: to keep humans unaware of the fact that they are being harvested as energy sources.

Though The Matrix bore marked similarities to such films as The Truman Show and Dark City, it was nevertheless idiosyncratic—its uniqueness enhanced by a then-surprising use of “wire fu” effects borrowed from Hong Kong cinema (and choreographed by a veteran of that genre). These involved the now familiar shots of characters floating through the air while they fight and dodge ammo using another effect called “bullet time,” in which space seems to warp and time slow. Revolutionary at the time, these devices have now been copied so much they’ve become visual clichés.

But the core of the film was its philosophy, driven by the aforementioned Simulacra and Simulation, a dense text that the directors, the Wachowskis, made their actors read before they even cracked the script. A sample: “Simulation . . . is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal.” (In the film, Neo hides his forbidden software in a copy of the book.)

The Matrix’s improbable success has led to video games, comic books, and two sequels—in addition to a quasi-religion called Matrixism. (“We must cause as much disarray in this fake world with the intentions to bring down those bastard machines and be free at last,” according to its official website. Okay, so it’s not the Dead Sea Scrolls.)

Since the days of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, SF has often been heralded for successfully predicting the future, and no film of the last millennium has been more prescient regarding the simulacra we’re all now mostly living in. No, Apple Inc. isn’t a sentient machine—yet—but the hyperreality of smart phones has become more “real” than the real. And it’s becoming “realer” all the time. This past April, YouTube announced plans to create live-streaming 360-degree videos on phones and browsers, bringing us, according to Wired magazine, “one step closer to The Matrix.”

© WARNER BROS./EVERETT

One of The Matrix’s many fight scenes showcasing “wire fu” techniques and a revolutionary effect known as “bullet time.”

2008 WALL-E

© DISNEY, COURTESY PHOTOFEST

WALL-E surveys his universe. “Animation is the ideal technique for SF as its only limits are the imagination,” Stephen Cavalier, author of The World History of Animation and co-owner of animation studio Spy Pictures, tells LIFE.

Here’s something to brighten your day: In several billion years, our ever-expanding sun will scorch the earth and cause the oceans to boil over, destroying human civilization—that is, if we haven’t already been obliterated during a collision between our galaxy and the Andromeda Galaxy or hit by a massive asteroid. Until relatively recently, these were the planet’s predominant doomsday scenarios, but of course our fatalistic focus has increasingly fallen on humanity’s own disastrous effect on the environment.

Long before the climate-change controversy reached a, well, fever pitch, the 2008 Disney-Pixar animated film Wall-E showed a refuse-ridden earth mostly abandoned by humans. (A TV commercial in the film announces: “Too much garbage in your face? There’s plenty of space out in space!”) While roaming the planet with his pet and friend, a cockroach, a waste-collecting robot named Wall-E finds his mechanized life transformed when he falls in love with Eve, a reconnaissance robot.

Billed as a cosmic comedy, the film is actually wistful, if not sad. And the fact that Wall-E is an endearing, relatable character even though he doesn’t speak for the film’s first 20-odd minutes is further proof of the genius behind Pixar, the animation studio that (in a twist worthy of SF) uses computers to make films that elicit deep human emotions.

Animated SF is a comparatively new phenomenon. “In years past, animation’s contribution to science fiction movies was mostly in the form of burlesques like Chuck Jones’s Duck Dodgers,” animation expert Michael Barrier tells LIFE. “Around the same time, effects animation was used in live-action SF features like 1956’s Forbidden Planet.” But the art form eventually took center stage in such feature films as Fantastic Planet (1973),Akira (1988), The Iron Giant (1999), and Ghost in the Shell (1995).

The use of CGI—most notably in Pixar’s 1995 film Toy Story—was a game changer for animation in movies. And in 2006, Richard Linklater (best known for such films as Dazed and Confused and Boyhood) added a distinctly adult-oriented work to the subgenre: A Scanner Darkly was rotoscoped, meaning that scenes with human action were first filmed, then traced over frame by frame, resulting in an animation/live-action hybrid. Like Blade Runner, Total Recall, and Minority Report, the film was based on the work of SF master Philip K. Dick.

2009 STAR TREK

© PARAMOUNT/EVERETT

CAPTAIN KIRK (Chris Pine) escapes from a pod in the snowy world of Delta Vega in J.J. Abrams’ feature-length Star Trek reboot.

What is there to say about the Star Trek phenomenon that legions of earthlings haven’t already said . . . or made money on? First launched as an NBC series in 1966, the show failed to attract an audience (viewers apparently preferred such fare as Bewitched and My Three Sons) and it was unceremoniously canceled in 1969. But it caught on with a vengeance when it was syndicated, creating a cultlike fan base of so-called Trekkies. In addition to spawning myriad conventions and fan clubs, Star Trek soon became a popular and lucrative media franchise with four further television series and 13 movies—and more to come.

The show’s creator, Gene Roddenberry, initially pitched Star Trek as “Wagon Train to the Stars,” a fact that highlights the frequent overlap between the SF and Western genres. (Roddenberry had cut his teeth writing for TV Westerns.) Broadcast on NBC and then ABC from 1957 to 1965, Wagon Train followed the adventures of pioneer families venturing from Missouri to California, while Star Trek followed the voyage of the Starship Enterprise on a five-year mission into “space, the final frontier.”

Along the same lines, Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, as mentioned, referred to 2001: A Space Odyssey, as How the Solar System Was Won, after MGM’s How the West Was Won. And Stephen King has called 1977’s Star Wars “an outer space Western just overflowing with pioneer spirit.”

Though the first feature film Star Trek adaptation (directed by Robert Wise, who also helmed The Day the Earth Stood Still) was a box office hit, it was widely considered a flaccid disappointment. But the franchise remained a popular juggernaut. The 2009 reboot, in particular, attracted hoards of new fans, grossing $385 million worldwide. The 2013 sequel was even more successful. Fifty years after Captain Kirk and crew first headed into the final frontier, the latest iteration in the franchise, Star Trek Beyond, is scheduled to hit multiplexes—and a new series is slated to launch on CBS this coming January. (So much for the five-year mission.)

In a wrinkle worthy of the best SF plots, the line between the Star Trek universe and reality has blurred: The first space shuttle was dubbed Enterprise; the Starfleet officers in Star Trek: The Next Generation use handheld touch-screen computers called PADDs; and Captain Kirk’s communicator has been called an inspiration for the first flip phones. Though we’ve yet to see the sort of technology that allowed the Enterprise’s Scotty to beam the crew up, the ashes of the man who played that engineer, James Doohan, were launched into space in 2012.

© PARAMOUNT PICTURES/EVERETT

THE STARSHIP Enterprise in 1982’s Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, a fan favorite after the franchise’s disappointing feature film debut in 1979. A new feature installment is scheduled for this summer, with yet another in the works, and a new TV series is slated for 2017.

2009 AVATAR

![]()

© 20TH CENTURY FOX/EVERETT

THE NA’VI NEYTIRI (Zoe Saldana) takes aim in James Cameron’s Avatar, the first in a series of five proposed films.

he Garden of Eden with teeth and claws” is how writer-director James Cameron described the lush moon of Pandora in his film Avatar. This is where the human-like Na’vi creatures live, their pristine paradise jeopardized by miners from Earth searching for a rare mineral called Unobtainium. It is also the setting for the film that (even after the Force awakened this past winter) remains the highest-grossing motion picture ever.

Of course, Avatar’s success was fueled by novelty: Cameron created new technologies that showcased CGI effects and 3-D in surprising and immersive new ways, using them as creative tools rather than gimmicks. (Most of the film’s grosses came from 3-D screenings.) But many felt the story itself was underwhelming, even derivative—and 3-D didn’t exactly become cinema’s “third great revolution” (after sound and color), as some had predicted. The film has failed to retain its claim on the public’s interest the way the Star Wars and Star Trek franchises have. Even so, in April Cameron announced plans to shoot four new Na’vi films concurrently, with the first installment planned for a December 2018 release.

2015 THE MARTIAN

© 20TH CENTURY FOX/EVERETT

STRANDED ON MARS, astro-botanist Mark Watney (Matt Damon) examines plants that have been destroyed after his artificial habitat (called the Hab) was compromised by an airlock malfunction. “I’ve either tried to crib from or outright rip off [Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey] numerous times in my career,” said The Martian’s director, Ridley Scott, “and I’ve never been able to do it quite right—until, possibly, now.”

In 1898, when H.G. Wells wrote his pioneering novel The War of the Worlds, many people believed that Mars was crisscrossed by canals and inhabited by so-called little green men. More than a century later, software engineer Andy Weir drew on the latest scientific information about the Red Planet, studying orbital paths and chemical reactions to research a novel he called The Martian.

Set in 2035, The Martian tells the story of Mark Watney, an astronaut marooned on Mars who travels nearly 2,000 miles from the planet’s Acidalia Planitia, a flat plain, to the crater Schiaparelli in hopes of being rescued. Throughout, he serves as a mouthpiece for Weir’s painstaking research: “Liberating hydrogen from hydrazine is . . . well . . . it’s how rockets work,” he writes. Maybe because of this kind of relentlessly geeky detail, the novel was rejected by multiple literary agents before Weir decided to self-publish it in installments on Amazon.com. As a finished book on Kindle, it went on to sell more than 35,000 copies in four months.

Suddenly agents were interested.

When the novel was published commercially in 2014, it hit the New York Times bestseller list and was released as a successful film by director Ridley Scott in 2015. (He also helmed Alien, and Blade Runner.)

“I went to the theatre alone to see The Martian,” David Koepp tells LIFE. “I was having a bad day. I was having a bad week, and I was in a foul mood. I sat down with a bucket of popcorn and for two hours I was transported—the movie was personal, relatable, beautifully made, and celebrated the wonders of human collaboration. I floated out of the theatre on a cloud of possibility. The Martian is every single thing I always hope for from the movies from the moment the lights go down. Those hopes are usually unmet by the end, so it’s a rare and beautiful thing when they are.”

On December 5, 2014, NASA’s first test flight of its Orion spacecraft—designed to send astronauts to Mars in the 2030s—successfully orbited the earth twice while carrying the first page of the Martian script. In October 2015, just days after the film opened, NASA introduced a tool that allows users to follow Watney’s journey across Mars—part of Mars Trek, a website that allows users to explore the Red Planet, no little green men in sight.

© 20TH CENTURY FOX/EVERETT

USING A TARP reinforced with duct tape and sealed around the edges with belts, Watney jury-rigs a seal for his exposed habitat after the airlock malfunction.