In chapter 8 we introduced the outward-mindset pattern—see others, adjust efforts, and measure impact. In this chapter we will explore how to begin using this approach by sharing how different individuals and organizations have successfully implemented the three elements of this pattern.

A few years ago, Arbinger was engaged by a large power company to help find ways to save time and money by reducing the inordinate amount of time leaders spent each year mired in planning the next year’s capital budget.

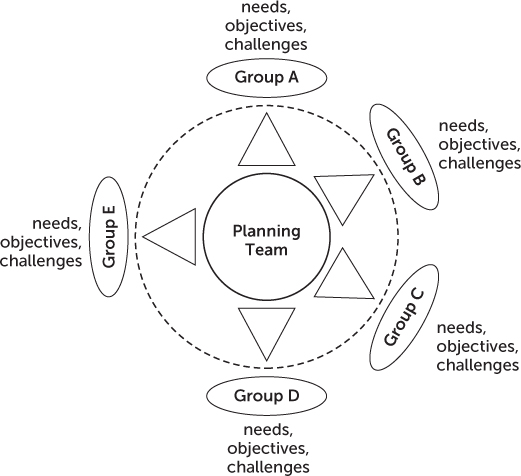

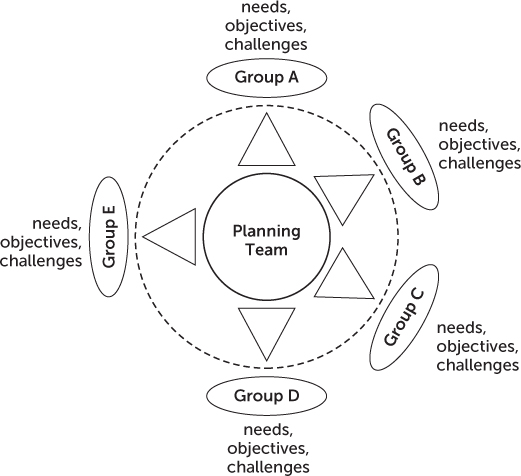

We spent about thirty minutes breaking down the budgeting process into its component parts. The forty or so leaders in the room gathered into groups or teams that were responsible for each part in the process: the planners formed one team, engineers another, and so on. On the whiteboard-paint walls, each team constructed an outward-mindset diagram for that group’s step in the budgeting process. The teams wrote their part of the process in the center. In a circle around that, they listed the names of the people and groups that they affected in the budgeting process. They then drew triangles facing outward in each direction and wrote next to each group what they understood of their needs, objectives, and challenges.

After a few minutes, the walls were covered with diagrams that looked something like diagram 13.

All members of the various groups circulated around the room to see if they should add their own or others’ names to any of the diagrams or whether they should add any key needs, objectives, or challenges that weren’t yet listed. Everyone had free rein to amend any diagram.

Seeing themselves correctly in relation to others, the leaders were now positioned to begin seeing others more clearly than before. They only needed to start looking. We invited the teams to take turns at the front of the room. Everyone else was given the opportunity to ask questions of each group to learn as much as possible about that team’s needs, objectives, challenges, and activities.

Diagram 13. The Outward-Mindset Project

The first group was the Planning team. Planning initiates the budgeting process at the beginning of every year by looking at projected community energy-consumption needs and energy-production possibilities and ultimately arriving at a mix of projects that would need to be engineered and constructed in the following year. This process took four months. Historically, the planners had passed their plans to the next group, the Engineering team, on May 1. In turn, the engineers would take two and a half months to design the projects and then pass their work to the people who handled step three of the process, and so on.

Something interesting happened when people began asking questions to more fully see and understand the needs and objectives of the planners: the planners immediately became interested in the needs and objectives of their questioners as well. What started as a question-and-answer session evolved into a conversation in the middle of which the group made a startling discovery: the planners knew 80 to 90 percent of the projects that would go in the final plan by mid-January. It took another three and a half months to finalize the last 10 to 20 percent. When the planners saw this, they suddenly knew an obvious way to shave three months off the budgeting timeline: the planners would no longer hold the whole batch of projects until all of them were finalized. Beginning immediately, they would forward the individual projects that would go into the final plan as soon as they knew them. This meant that Engineering could start its part of the process in January rather than May. This change made a huge difference. And that was just the first group.

Why couldn’t that change have happened earlier? It could have, of course. These were highly competent people. But without a framework that makes the solutions that already exist in an organization discoverable, many tremendously helpful solutions lie dormant. It’s as if an organization consists of many potential Bluetooth connections, most of which have not been turned on. When you make those devices discoverable to each other, they can begin to talk. And when they do, they figure out how to make things better. You can make them discoverable by instituting opportunities to see others. This was one of the main benefits of the BPR process that Alan Mulally instituted at Ford, as we discussed in chapter 8. The weekly meetings provided an occasion for the Ford executive team to learn to see each other.

Journalist Brenda Ueland, in her insightful essay on listening, Tell Me More: On the Fine Art of Listening, provides interesting insight regarding the simple potency of trying to “see others” through listening. “Listening is a magnetic and strange thing, a creative force,” she writes. “Think how the friends that really listen to us are the ones we move toward, and we want to sit in their radius as though it did us good, like ultraviolet rays. This is the reason: When we are listened to, it creates us, makes us unfold and expand. Ideas actually begin to grow within us and come to life.”1

Ueland then describes the difference between how she used to interact with others and how she learned to interact with people after she learned to be interested in them. Think about how her description of her former way summarizes so much of what happens in the sales processes of organizations and in company meetings, as well as in interactions in our social lives: “Before … when I went to a party I would think anxiously, ‘Now try hard. Be lively. Say bright things. Talk. Don’t let down.’ And when tired, I would have to drink a lot of coffee to keep this up. Now before going to a party I just tell myself to listen with affection to anyone who talks to me, to be in their shoes when they talk; to try to know them without my mind pressing against theirs, or arguing, or changing the subject. No. My attitude is, ‘Tell me more.’ ”2

Rob Dillon experienced the same kind of shift that Brenda Ueland did. Rob is the fourth-generation member of his family to lead Dillon Floral, a wholesale florist that serves Pennsylvania and neighboring Eastern Seaboard states. His company faces a challenging market, as its historical customers, small local florists, have been declining steadily in number with the rise of the superstores that sell flowers. To retain its shrinking customer base, Dillon Floral included in-person customer visits as an important part of its strategy. But Rob detested these visits. He knew that his customers were struggling, and he didn’t like how he felt walking into the stores of struggling customers and trying to persuade them to buy this or that Dillon Floral product. Consequently, over the years, Rob made fewer and fewer visits—until, that is, he learned the power of really seeing others that Ueland writes about.

Rob disliked engaging with his customers because he had been making self-focused visits rather than others-focused visits. He had mainly been interested in trying to get the people he was calling on to buy his products. He interacted with his customers in the same way Ueland interacted in social gatherings before she learned simply to get interested in and be open to others. Rob felt the pressure to perform, to impress, to sell. “I used to walk into meetings with customers with an agenda,” he said, “and I had a whole bunch of fear.” He says that when he learned just to get interested in seeing others, this all changed.

Today when Rob calls on customers, his only thought is, How can I help? He isn’t there to impress the customers, and he certainly doesn’t perform. He just wants to figure out what he can do to help them, and that starts with seeing—trying to understand the needs, objectives, and challenges of others. With this new focus, Rob now spends one to two days every week calling on customers. He’s been surprised to discover that he loves it. As a direct result of this, clients that had quit purchasing from Dillon Floral have since returned, and many that had been thinking of turning elsewhere instead felt a renewed commitment to their partnership.

Rob describes the change this way: “Since learning about the outward mindset, I simply go into meetings with customers wanting to learn whatever I can about their needs, objectives, and challenges. I would rather walk into a flower shop stupid than smart. I say to them that I want to learn how we could be more helpful to them. And then I just listen. Seeing them as people, I can very easily empathize with them no matter what they say. There is nothing to fear. I’m just there to help.”

This comment is revealing. When, with an outward mindset, Rob is really interested in seeing others, he naturally feels a desire to find ways to be more helpful—which brings us to the second step in the outward-mindset pattern: adjusting our efforts.

A longtime colleague of ours, Terry Olson, tells of the following experience that began in a workshop he was conducting for public-school teachers. They were using a room at a lockdown educational facility for elementary-aged children with severe behavioral problems. Some of the teachers from that school were eavesdropping at the back of the room.

In the middle of the presentation, one of these teachers at the back asked a question about how to handle a boy who was becoming increasingly unmanageable. In fact, although they had frequently used the “time-out” room (a small, locked, carpeted cubicle used to isolate disruptive children) to discipline the boy, he seemed to be getting worse. He would settle down briefly after a time-out experience and then would become even more disruptive than before. The most dramatic of his antics had occurred the prior week, when a serviceman delivering soda to the vending machines left a school door open while he maneuvered a loaded hand truck inside. The unmanageable boy, Toby, had just bolted from his classroom (a frequent occurrence) and was hiding in the refreshment area when the delivery gave him the opportunity to escape.

Running out into the schoolyard, Toby tore off all his clothes and began running through the park. Before long, Toby, naked, was being chased down by a score of panicked teachers. “So, what do you do with a student like that?” the teacher asked.

Terry told the questioner that he had no magic solution but suggested that if the boy became increasingly unmanageable after being locked in the time-out room, maybe he was not responding to the particular punishment as much as he was rebelling against being seen and treated like an object. “Objects do what you want them to do,” Terry explained. “You can throw a washcloth in the sink, kick a soccer ball across a field, or push clothes into a laundry bag. But when you try to throw, kick, or push people, they often resist. Toby might be resisting the idea of being a ‘thing.’ ”

Terry suggested to the teachers that if none of their disciplinary techniques were working with Toby, perhaps they should consider a different approach. Instead of chasing him down when he bolted from class and putting him in the time-out room, Terry invited them to imagine new possibilities. He said, “What if you asked this question of yourselves: If I were to give my heart to this boy, what would occur to me to do?” He then invited them to act on what occurred to them to do.

Two weeks later, Terry was back in the facility for another workshop session. He wondered what, if anything, had developed with Toby. The teachers from the school were eager to report. One woman recounted the following experience:

Toby ran out of my room two days after we had talked, and instead of sending my aide after him immediately, I continued teaching. After a few minutes, I turned the class over to my aide and went looking for Toby myself. I found him in the auditorium, “hiding” under a blanket. Toby hid as many second graders do—his leg was sticking out from under the blanket. I asked myself that question, “If I were to give my heart to this boy, what would occur to me to do?” Immediately, I thought of those days as a child when I had played hide-and-go-seek. Almost on an impulse, I got down on the floor and crawled under the blanket with Toby. He was more than startled. I said, “Look, I can’t play hide-and-go seek with you now; I’ve got a class to teach. But if you still want to play when it’s recess, I will come and find you.”

At recess I went back to the auditorium. It seemed he had not moved. I pulled the blanket off and said, “Found you!” I then explained I wanted to be “it” again and threw the blanket over my head. “I’ll count to twenty-five,” I said. He stood there until I got to ten. Then he hesitatingly ran out of the auditorium. I searched. I found him in a classroom pressed into a vertical broom closet. I started counting again. I found him for the third time as the bell rang. I explained that I had to go teach now.

Twenty minutes later he almost sneaked into my classroom and slid into his chair. He has not been perfect, but I have been different. When he misbehaves, that question of yours has become an echo in my brain: “If I were to give my heart … ?” Sometimes I stop everything and ask him a question. Sometimes I ask him to help someone else. Sometimes I explain that I need help. Sometimes I explain to him that he just “can’t do that,” and I go on. He settles down. It is a day-by-day thing, but I am different with him. He seems different to me, even when he acts up.

This teacher discovered what all outward individuals and organizations know: real helpfulness can’t be made into a formula. To be outward doesn’t mean that people should adopt this or that prescribed behavior. Rather, it means that when people see the needs, challenges, desires, and humanity of others, the most effective ways to adjust their efforts occur to them in the moment. When they see others as people, they respond in human and helpful ways. They naturally adjust what they do in response to the needs they see around them. With an outward mindset, adjusting one’s efforts naturally follows from seeing others in a new way.

This brings us to the third element of the outward-mindset pattern—measuring one’s impact on others.

For people who are implementing the outward-mindset pattern, what might measuring impact look like? And how might a person or organization go about doing it? Consider the following stories.

Attorney Charles Jackson, a third-year associate lawyer at a midsized law firm, was attending a leadership course we were conducting. Charles spent about 90 percent of his time working on issues for clients that had been brought to the firm by partners in the firm. He spent the other 10 percent of his time on client work he himself had generated for the firm. As we discussed working with an outward mindset, Charles could not get two of his own clients out of his mind. Both of them were unhappy with the job Charles had done. But until that moment, Charles hadn’t been overly concerned about this. Not every client is going to be happy with you, he had assured himself. There’s nothing you can do about that. Besides, I did the work, even if they weren’t happy with some aspects of it. During the workshop, we presented the idea that working with an outward mindset requires that people take responsibility not just for what they do but also for the impact of what they do. As Charles began considering this idea, these client situations started to seem a bit different to him.

One of the clients had been unhappy with how long it had taken Charles to handle his issue. Until then, Charles had brushed the complaint away. As he now thought about it, however, he realized that his client had a legitimate gripe. Charles hadn’t given the work high enough priority, and his slow pace had created difficulties for his client that he had never apologized for or addressed.

The second client had been surprised by the bill Charles sent him. Charles hated talking about billing and had avoided the conversation altogether with this client. The first time the client learned about Charles’s cost was when he received the invoice Charles had sent.

As Charles considered his impact on these clients, he felt he should return their money. So he did. One of these clients lived in a different state, so Charles wrote a letter of apology and enclosed it with a check. The other client lived in Charles’s city, so Charles offered his apology and delivered the check in person.

How many times do you suppose attorneys have willingly and on their own returned the money clients have paid them?

Charles returned the money in May of that year, and he began tracking his impact on his clients by checking in with them on a regular basis to make sure that he was meeting or exceeding their expectations. Then something interesting happened. These clients started talking to their friends and acquaintances about their honest and conscientious lawyer. By July, Charles was receiving seven new client matters per week. By November, that number had grown to thirteen per week, and Charles was employing three of his law-firm colleagues nearly full-time on client work he had brought in. In March, he left his job to start his own law firm.

All of this happened because Charles made a disciplined effort to track and hold himself accountable for his impact on his clients. He called his regular check-ins with his clients self-accountability checks. This approach to measuring one’s impact requires nothing but a willingness to stay in regular conversations with others about whether they feel one’s efforts are helping them or not.

Another way to measure impact is to find metrics that show a person or organization what others are able to accomplish or achieve as a result of their efforts. This was what a nonprofit organization called Hope Arising found a way to do.

Hope Arising is dedicated to assisting orphaned and at-risk children in rural Ethiopia. Eager to meet an urgent need for clean water in the drought-stricken areas where these children live, the team diligently worked to improve their ability to deliver more and more clean water. Naturally, they measured efforts in terms of their output: gallons of clean water delivered.

When the Hope Arising team learned about the outward- mindset pattern, they saw that although they had discovered a need and were working on adjusting their efforts to meet that need, they had never thought about how to measure the impact of their work. Consequently, they didn’t actually know whether they were meeting the needs of the orphaned and at-risk children they were trying to help. They began to consider how they could measure their actual impact.

They knew that they needed to assess what was happening on the ground. “What kind of metric,” one team member asked, “would show us our impact and not just our output?” “What impact do the people want?” another responded. “What are they hoping clean water will do for them? If we had answers to those kinds of questions, maybe we could figure out what we should be measuring.”

With these questions in mind, the team started talking to villagers across the region. In hut after hut they heard the same thing: “We need clean water because we need our kids to be able to go to school. When our kids are sick from dirty water, they miss school. And if kids can’t go to school, the traveling school-teachers don’t get paid. So they move on to other villages. But if our kids don’t get educated, they’ll never escape this poverty.”

This was a revelation to the Hope Arising team in two ways. First of all, they had found a way to measure their impact: number of days children are in school. Measuring this would show them their impact on what mattered most to the recipients of their services, and they could easily get this data from local governments. The second revelation was this: they weren’t really in the water-delivery business; they were in the helping-kids-getto-school business. This realization got them thinking about all kinds of ways they could be helping in addition to ensuring the delivery of clean water.

As Hope Arising discovered, engaging in the first two steps of the outward-mindset pattern is not enough. If we don’t measure the impact of our efforts on the objectives of those we are serving, we will remain blind to important ways we need to adjust and will end up not serving others well.