GLYNIS PETERS HUNCHES OVER her desk in a makeshift office at the Teen Ranch Ice Corral in Caledon, Ontario, scanning yet another checklist for this Team Canada selection camp. Hockey bags, video cameras and posters lie amid the boxes that surround her tiny desk. Peters’s wavy black hair is peppered lightly with silver, no doubt partly due to her demanding schedule and the diverse responsibilities she must assume as manager of women’s hockey at the Canadian Hockey Association (CHA). This week, in her capacity as national team manager, she’s overseeing an intensive session that involves fifty-three players from across the country, as well as five coaches from the national team pool and other advisers. It’s been a hectic week of interviews, practices and games. Later tonight before the intersquad game, she must squeeze in time for a short talk to parents and kids as part of a Hockey Hall of Fame presentation.

Judging by Peters’s schedule, things look good for women’s hockey in Canada. The CHA is the only hockey association in the world that employs a manager to oversee the women’s game. Registration is burgeoning and Team Canada is expected to win its fourth consecutive gold medal at the 1997 world championship and its first gold medal in the 1998 Olympics. Furthermore, in 1995, after a long hiatus, the final game of the national championship returned to television, thanks to a new sponsor. At a quick glance these changes seem to mark a new trend in Canada’s national pastime: the women’s game finally appears to be receiving the money, support and recognition it deserves.

Despite these gains, women’s hockey in Canada remains a second-class citizen within the Canadian Hockey Association and its branches. The reasons are many. First and foremost, the CHA operates on what could be called the “little sister principle,” a principle that informs the way most male-identified sports function. Like the legions of girls who have played in goal for their brothers when an extra player was needed, women in the game today are more tolerated than respected. Female players are still largely looked upon as the little sisters who don’t really belong in hockey. The little sister principle permeates both national and provincial hockey organizations. The success of Team Canada, the appearance of female players on television and the decision to include women’s hockey for the first time in the 1998 Olympics would suggest that women have managed to counteract this principle in the 1990s. Professional hockey sets the standards for the game, and its overwhelming influence underscores the little sister principle. Given the widespread adoration of the NHL, it is not surprising that there is little room for the amateur female game to thrive. As Canadian Press sports journalist Alan Adams puts it, “[Women] are tolerated, they are appeased. Hockey is a male game.”1 The underlying pro hockey mentality only intensifies the benign neglect and patronizing attitudes that continue to keep women off the ice, away from sponsors and absent from the media.

In order to appreciate the way in which professional hockey influences amateur hockey, and in turn, women’s hockey, it is essential to understand the Canadian Hockey Association, the national governing body of the sport in Canada. (The CHA was known as the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association [CAHA until 1994.) In the first decade of this century, professional and amateur hockey organizations sprang up across the country. The CAHA was founded in 1914 to establish national rules and standards along with interbranch and international tournaments in the amateur game. By the late 1920s the National Hockey League, founded in 1917, prevailed as the dominant league for professional teams.2 Some amateur junior and senior teams were closely associated with the NHL, but amateur leagues also enjoyed tremendous popularity in the twenties and thirties, competing for both players and fans with the pro leagues. Afraid of losing more players to the NHL, in 1935 the CAHA signed a contract in which the NHL agreed not to recruit junior players and to pay senior teams for players acquired by NHL teams. But a series of agreements over the next ten years gradually eroded the control the CAHA had over its players and the game. “Indeed, by 1947 the CAHA had become little more than a junior partner of the NHL; it couldn’t even determine the eligibility of its own members or change its own playing rules without NHL approval,” write sociologists Richard Gruneau and David Whitson in their book, Hockey Night in Canada, a cultural critique of hockey.3

It wasn’t until the 1960s that concern surfaced about professional hockey’s domination of the amateur game. This concern stemmed from Canada’s lacklustre performance at world competitions throughout the decade. A national task force on sport, with an emphasis on hockey, was soon created to look into this situation. One of the issues that concerned the task force was “the refusal of professional teams to loan promising junior players to the national team as well as the NHL’s general antagonism towards the national team concept.”4 As a result of the task force, a separate quasi-professional organization called Hockey Canada was formed in the late 1960s to represent Canada at the international level and to develop a national team. This new organization (whose board of directors included representatives from the NHL and the National Hockey League Players Association) proved to have little influence over the NHL and so the links between amateur hockey and professional hockey remained strong. It wasn’t until 1977 that the CAHA reestablished its presence at world competitions with the men’s junior national team, and the women’s national team in 1990.

Parental concern about the high incidence of injury led several provinces, including the Ontario Ministry of Community and Social Services, to launch inquiries into amateur hockey. The recommendations that resulted from those inquiries focussed on the need to educate coaches and players’ parents about the value of participation versus winning at all costs.5 In the 1980s thousands of boys abandoned the game. From 1983 to 1989 male minor hockey suffered a 17.4 percent drop in registration while registration in the female game—a game without the violence and far from the pro hockey sphere—increased by 68.6 percent.6 Until the 1990s, when the CAHA launched new programs directed at developing fair play and making hockey more fun, very little changed in male minor hockey. The positive results were evident in 1994–95 when the CHA reported that it had a total of 450,884 male minor hockey players (in all age categories under senior and junior). This represented an increase of almost 30 percent since the 1989–90 season.

Minor hockey is the foundation of amateur hockey in Canada, accounting for more than 90 percent of the CHA’s registered players. In 1994–95, 513,207 players were registered with the CHA, 19,050 of whom were female. If coaches, parents and volunteers are added, the total figure balloons to approximately four million.7 In addition thousands of male and female Canadians play on high school, university or recreational hockey teams which are not registered with the CHA. The estimated number of girls and women who play on these teams (some belong to male teams) is 20,000.

The CHA’s involvement with women’s hockey is relatively recent; in fact, it is only a few decades old. However, the first female game was recorded in Ottawa, Ontario, in 1891. Women’s hockey flourished at the turn of the century, and according to newspaper reports, pockets of female players were scattered across Canada. Some were as far north as Dawson City, others as far east as the shores of Newfoundland. These female players competed on outdoor rinks lit by lanterns, the boards piled high with snow. In the freewheeling 1920s and 1930s, the national championship for women’s hockey meant the top women’s teams from the East (including Quebec and Atlantic Canada) and the West vied for the Dominion title. Teams travelled and lived on trains, playing in front of enthusiastic audiences for the Canadian crown. In 1935 the Preston Rivulettes drew six thousand fans to the arena in Galt, Ontario, for the two-game playoff for the national title against Winnipeg.8 The championships were arranged by women’s hockey representatives across the country but fluctuated according to the availability of funds for facilities and travel.

The Rivulettes dominated women’s hockey from 1930 to 1939. Their astonishing win-loss record of 348–2 stands unrivalled in the history of Canadian hockey, male or female. In Atlantic Canada and the West several leagues evolved from teams set up by telephone company employees. “Telephone teams” from Sydney and Halifax competed and there was even a “telephone league” in Manitoba. Telephone teams were also members of the Quebec Ladies Amateur Hockey League, with whom they faced off for the Lady Meredith Trophy to claim the provincial title.9

While the female game’s popularity began to decline in the 1930s, the pro male game’s popularity soared. The NHL took over the Stanley Cup in 1926, and in 1931 fans across Canada listened to the first radio broadcasts of games by Foster Hewitt, who became known as the “voice of hockey.” In 1952 television ushered in a new era with the program “Hockey Night in Canada.” Indoor rinks proliferated and a plethora of men’s hockey associations quickly gained control of the prime ice time in the arenas, effectively edging women off the ice. Women’s hockey had also lost many of its leaders after World War II, leaders such as Bobbie Rosenfeld, a hockey star, allround athlete and sports columnist, and Marie Parkes, the organizer of intercollegiate hockey.10 Moreover, the conservative 1950s with their “Ozzie and Harriet” family values sent women back to the kitchen and into more traditional roles. They were now expected to cheer for television hockey heroes rather than play their own game.

Helen Lenskyj, a sport sociologist at the Toronto-based Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, contends that the widespread input from conservative sectors within education, the recreation movement and the church led to the demise of interschool and intercollegiate competition for girls as early as the 1930s in most of the US and in some parts of Canada.11 By the forties and fifties, the distinction between male and female activities had been concretized. This meant that most of the state-launched fitness and recreation programs established during the war maintained the custom of providing team sports for males and “fitness activities” for females.12

Where girls and women were concerned both Canadian and American athletic organizations emphasized participation rather than winning in order to avoid the hazards of overly aggressive play, a win-at-all-cost mentality, and the commercialization associated with boys’ and men’s sports. But the conservative tone in community sport had a stifling effect on women, which lingers even today. Sociologist Mary Keyes writes:

[This attitude] was exhibited by nineteenth-century male sport leaders, notably the French patriot Baron Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympics, which began in 1896. He espoused the view that women’s sport was against the ‘laws of nature’ and therefore reserved the modern Olympic Games for men. This paternalism, emphasizing the biological differences between men and women, also characterized the attitude of doctors, educators and legislators. The rules and regulations for sport perpetuated the view that girls and women were fragile and inferior—physically and psychologically—to their male peers and should be protected from injuries that were bound to result from any exertion in sport.13

The effect of this ideology at the university level was especially devastating. In Ontario and Quebec competition among teams from McGill University, Queen’s University and the University of Toronto was sporadic during the 1920s and 1930s and the Women’s Collegiate Ice Hockey League ceased altogether in 1933.14 It was not until the 1960s that university women slowly began to reclaim their place in hockey, with Ontario emerging as the leader. Female students successfully lobbied universities in Ontario to reestablish a women’s interuniversity hockey league.

The community game also reemerged with events such as the Canadettes Dominion Ladies Tournament held in Brampton, Ontario, in the 1967–68 season. Invitational tournaments for senior players were held in various parts of Ontario, from Hailebury to Ottawa. In the same year, women’s hockey boasted two thriving leagues in Montreal, and several clubs travelled as far as Manchester, New Hampshire, to play exhibition games. In the 1960s the Western Shield tournament was also launched, involving the four Western provinces.

In the meantime a new game, ringette, both paralleled and inhibited the development of women’s hockey. Ringette’s inventor, Sam Jacks, a director of parks and recreation in North Bay, devised the sport as a female alternative to hockey. In 1963 he created this hybrid game of lacrosse and basketball, which is played on ice with skates; players use a straight stick to shoot a rubber ring. Although his three sons were excellent hockey players, it didn’t occur to Jacks that girls should also play hockey, according to his wife, Agnes.15

Ringette caught on very quickly. It offered a safe, all-female environment in which girls could compete without fear of harassment. And there were no male standards against which the game could be judged. The majority of parents considered hockey too violent for girls. This gender sport with its feminine image seemed the ideal solution. A study of ringette players conducted by Aniko Varpalotai in 1991 indicated that many girls had longed to play hockey when they were younger but were “redirected by parents or others to a more suitable sport for girls, usually figure skating. Their participation in ringette frequently evolved from both a dissatisfaction with figure skating and peer influence.”16

In 1969, six years before the Ontario Women’s Hockey Association (OWHA) was formed, ringette enthusiasts founded the first provincial ringette association in Ontario. In the next decade organizers established a national office and launched national championships. The western provinces and Quebec also played a key role in the quick growth of ringette. Eight years later the association created the Ontario Ringette Association Hall of Fame. By 1983, twenty years after the first game, there were more than 14,500 registered ringette players. During the same year—ninety-two years after the first female hockey game—the number of players registered in women’s hockey was a mere 5,379, less than 40 percent of ringette’s numbers.17

Ringette thrived in the seventies and eighties. Its enthusiastic volunteer base swelled thanks to highly organized national training programs. One of ringette’s greatest strengths was its ability to attract parents as volunteers. By 1994 there were 12,000 certified coaches, trainers and managers among the volunteers, in addition to 2,600 officials, both unusually high figures, given the 27,200 registered players. Volunteers were instrumental in increasing membership, which climbed rapidly. They also helped the sport’s national organization to establish credibility in the larger sports community. Ringette holds national championships for four age groups with the help of a whopping six hundred local associations. This number provides strong evidence of the game’s acceptance at the community level. Both women’s hockey and ringette were added to the Canada Winter Games in 1991. So far, however, ringette has failed to gain Olympic status, and only four countries competed against the Canadian team in the 1994 world championship.

Ringette has been particularly appealing to young women and girls because of its feminine image. The vast majority of ringette players are eighteen years old and under. In fact, 80 percent of Ontario’s 10,000 players during the 1994–95 season fell into this minor category. By comparison, in the 1994–95 season participation in the eighteen-years and under category in female hockey accounted for 61 percent of the total registration. Ringette’s appeal to this age category lies in its “girls only” image and the fact that it is supported by parents and communities alike. The names of the various subcategories within this category leave no room for confusion about one’s sexual identity. They are: Petites (for nine-year-olds and under), Tweens, Belles, Juniors, and Debs (the latter is short for debutantes and is for twenty-two-year-olds and under). Research has shown that a high percentage of girls drop out of organized sports in their early teens when boys and peer pressure come into play. As sociologist Helen Lenskyj puts it, “the power of compulsory heterosexuality hits them with a bang … [they feel] they should not be able to run faster than a boy or play tennis better than a boy or do math better than a boy.”18 Indeed, when a survey was conducted of American girls aged seven to eighteen, researchers found that 36 percent of the subjects maintained boys made fun of them when they played sports.19

The feminine image of ringette has clearly attracted sponsors, who are undoubtedly aware of the sport’s appeal to parents and local communities. Six official sponsors signed on for the 1994–95 season, including Shoppers Drug Mart and the Royal Bank. The Royal Bank also sponsored a full-colour ringette poster, 10,000 of which were distributed by provincial associations. In recent years, promotions for the sport have included an incentive program that gives players who bring in a new recruit half-price registration or a free jacket. A newsletter, The Ringette Review, began in 1979, and by 1995 circulation had risen to 34,000.20

Despite its appeal, ringette has recently proven to be a training ground for future hockey players, especially in communities in the West where girls’ and women’s hockey did not exist in any substantive way in the early 1960s and 70s. Excited by the challenge of hockey, Albertan Judy Diduck gave up ringette in 1990 and went on to become a three-time member of the women’s national hockey team. Diduck had signed up for ringette when she was ten years old and did not play on a female hockey team until she turned nineteen. “I didn’t really know [women’s hockey] existed,” she said. “Certainly not in any organized way. I didn’t realize there was a league of any sort until a friend told me about it.”21

Interest in ringette is now fading. This is partly due to the fact that bodychecking was removed from women’s hockey in 1986, which helped many ringette players who had wanted to play hockey but decided not to because their parents feared they would be injured. Registration for female hockey began to climb following the bodychecking ban, the world championship, and the inclusion of women’s hockey in the Canada Winter Games. Between the 1990–91 and 1994–95 seasons the number of players more than doubled, going from 8,000 to 19,000. In the same time period, ringette added less than 900 players to its roster. Despite relentless organizing and promoting, ringette is still not fully accepted as a legitimate sport. The sport’s advocates fight to get attention from the media for a game many now view as a quaint and outdated substitute for female hockey. In 1994 The Sports Network (TSN), Canada’s only private all-sports broadcaster, ceased televising ringette’s national championships due to poor ratings. Undaunted, ringette organizers produced and televised their own video of the 1995 championship using air time donated by TSN.

In the early 1990s ringette, like women’s hockey, enjoyed the financial benefits of the Ontario government’s policy of full and fair access for female sports. It received a windfall of $139,000 from the Ontario government in the 1994–95 season compared to the $89,839 women’s hockey received. However, at the federal level of government, ringette has recently lost its funding. Although it received $160,000 in federal funding in 1994–95, beginning in 1996–97 it will receive no money. This loss of funding has been attributed to the fact that the sport is not represented at the Olympics and has limited international participation. The loss of federal funds, stagnant registration and the increasing acceptance of women’s hockey could blow the final whistle on this sport anachronism.

While ringette gathered momentum in the seventies and early eighties, women’s hockey inched along, largely at the senior level in most provinces. Minor hockey was virtually non-existent outside of Ontario, where registration surpassed the other provinces by climbing from 120 teams to 302 teams from 1979 to 1989. The cost of equipment and travel were inhibiting factors, as were parents’ fears that their daughters would injure themselves. Bodychecking was a part of the game until the mid-1980s in most provinces. The misconception that girls are more fragile than boys and therefore more prone to injury was commonplace and highly effective in impeding girls and women from entering the game. Moreover, since the media had taken no interest in the sport since the 1930s, and since there was no national women’s championship, many potential players were still unaware that women played hockey.

In the early 1970s women’s hockey representatives launched associations in Alberta, Prince Edward Island and British Columbia within the male provincial hockey organizations. Ontario’s female hockey representatives, inspired by the province’s rich history, the growth of regional tournaments and strong leadership, founded a separate provincial women’s hockey organization, the Ontario Women’s Hockey Association which was instrumental in driving the game forward nationally. By the late 1970s spokeswomen for women’s hockey from several provinces pressured the CAHA to commit government funding to national development seminars. Abby Hoffman, then director of Sport Canada, channelled money to the CAHA to fund a series of workshops to discuss the status of women’s hockey across the country. These workshops dragged on into the early 1980s and accomplished very little. Finally, in May 1981 the CAHA created a Women’s Hockey Council whose director would become a member of the CAHA Board of Directors.

In order to promote the women’s game at the national level, advocates of women’s hockey first had to overcome the attitudes of the CAHA and its branches. The OWHA was determined to reestablish a senior national championship with representation from all provinces. (In the 1930s only two teams, winners from the East and West, played off for the national title.) The OWHA began to lobby the CAHA to fund and support a national championship. Following a letter and phone campaign from women’s hockey representatives across the country the CAHA finally agreed in November of 1981 to request funds from the federal government, which it would in turn use to launch a national championship in April of 1982. The OWHA convinced Shoppers Drug Mart to sponsor the event and donated two cups, one for first place, the other for second place. The former was called the Abby Hoffman Trophy, in honour of the women’s sports pioneer; the latter, the Maureen McTeer Cup, named after the wife of then Opposition leader Joe Clark, who had helped lobby for the championship. (A third place trophy, the Fran Rider Cup, was added in 1984 to honour the OWHA president.) Two months before the championship, the CAHA finally sent a letter of endorsement which sanctioned the competition as an official CAHA event.

The senior national championship was one of the pivotal events that drove the women’s game forward in the 1980s, compelling each province to hold its own provincial championship. For example, the New Brunswick Women’s Hockey Association launched its first championship in March 1982 so that it could send a team to the national championship. The OWHA used the event to stimulate membership by stipulating that any Ontario team that wanted to compete in the provincial and the national championships had to be a member of the OWHA. Furthermore, the first few national championships attracted major sponsors and generated media attention, which had been absent from the women’s game since the 1930s. Most importantly for players, they could now enjoy the adrenaline rush triggered by the excitement of competing at the national level, an experience their male counterparts had long been able to enjoy. They could also test their skills against other elite athletes and ultimately savour the accolade “the best in Canada.” Off the ice, this national event also provided provincial leaders in the women’s game with the rare opportunity to network. In fact it was during the national championship that the CAHA met with provincial representatives to officially launch its first-ever female council, originally called the Women’s Hockey Council.

Despite the significance of the first Female Council in the CAHA, the council proved to have very little influence or power within the CAHA or its branches. Members encountered a firmly entrenched subculture, which has been aptly described by sociologists Richard Gruneau and David Whitson:

Because women have always been excluded from hockey’s institutional structure, even though women have been playing hockey-like games for almost as long as men have, organized hockey developed as a distinctly masculine subculture, a game played (at the organized level) almost exclusively by men and boys and a game whose dominant practices and values have been those of a very specific model of aggressive masculinity.22

What started as a game soon came to represent an exclusive male club at which women weren’t welcome. This “club” represented a physical as well as cultural space, as most arenas have been monopolized by men and boys. As Gruneau and Whitson observe, “The increasing presence of girls and women in areas of life that were formerly all male really does reduce the spaces in our culture where ‘men can be men and male solidarity can be rehearsed.”23

The Female Council director, Rhonda Leeman, had voting privileges on the CAHA board, but Leeman maintains the council’s power was negligible. At her first CAHA annual meeting in 1982, she presented fifteen recommendations that called for financial assistance as well as a separate constitution that would allow the council to be independent, both in terms of its operation and finances.24 None of these recommendations or others giving women’s hockey more independence were ever passed by the male-dominated board.

Although the Female Council was allowed only a small degree of control over the women’s game, it steadfastly maintained its priorities. Educating parents and young girls about the distinctions between women’s hockey and men’s hockey was a central component of the council’s tasks. Another task that was critical to advancing the women’s game was the establishment of training programs for referees, coaches, trainers and players. The council also assumed the task of managing the senior national championship in conjunction with the host city. In 1993, it also assumed the responsibility of managing the junior national championship.

Despite the overwhelming men’s club atmosphere of the CAHA, the Female Council managed to accomplish some things. One of its most significant initiatives was winning approval to have girls’ hockey included in the Canada Winter Games in 1991. The Games had been created in 1967 to encourage community development and participation in winter sports, but until 1991 hockey was limited to boys. With the inclusion of girls under age seventeen, these female players now had their first formal development program. The selection and training camps for the Canada Winter Games drew new players and sparked provincial participation in this underrepresented age category. (Prior to 1990 many provinces, with the exception of Ontario, had no hockey development programs for girls under the age of twenty.) A national program such as the Canada Winter Games drives the sport within small communities, where girls may want to play but may not receive any encouragement from parents or coaches. Indeed, the inclusion of girls’ hockey in the Canada Games was largely responsible for the almost 40 percent increase in CHA registration for female hockey in 1991–92.

The Female Council’s second major accomplishment, the launching of a national championship for the under-18 category in 1993, provided further motivation for provinces to develop programs for this often-ignored age group. Because of the small number of players in this age group, in 1993 only six teams competed: two from Ontario and one each from Alberta, Prince Edward Island, Quebec and Saskatchewan. This championship will now take place every four years with the Canada Winter Games held in between. Some regional championships and jamborees have gradually been added to motivate these intermediate players. Although these are important advances, the CHA representatives—even those on the Female Council—are all too ready to justify the overall lack of equity. Karen Wallace, who has been the council director since 1991, defends the infrequency of the junior national championship by arguing that the CHA does not want to push young girls into competition too early and that the championships also strain the already low budgets for the teams. Wallace is correct in saying that women’s hockey budgets are low; however, the CHA has done little to remedy this. Inadequate financing continues to hamper women’s hockey. After six years of allowing volunteers to administer the women’s game, the CAHA finally hired a coordinator on contract in 1988. Only following the success of the 1990 world championship did the CAHA hire a permanent manager for women’s hockey, Glynis Peters.

Peters emits boundless energy and is intensely committed to the game. Coming from an athletic family, Peters participated in a variety of sports in high school and university, including a three-year stint on the Ontario provincial field hockey team. After graduation, while travelling in France, Peters had the opportunity to join a climbing expedition to Mount Everest. To do so, Peters raised money and even flew to Beijing to get the necessary permit. With only a few climbs in the French Alps under her belt, she and her partner joined three experienced climbers. They trekked to Base Camp 2 at approximately 6,500 metres (four miles) above sea level with no oxygen—a remarkable feat for a rookie climber. Peters returned to Canada in 1990 in time to apply for the job of manager of female hockey at the CAHA. The thirst for challenge that led her up Mount Everest and the teamwork required to cope

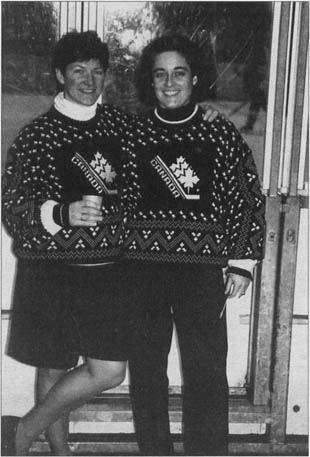

Glynis Peters (left), manager of Canada’s national team and Shannon Miller (right), assistant coach at the Athletes Village, Lake Placid, 1994 world championship.

with the adverse conditions she encountered there serve her well at the CHA. Building a presence for women’s hockey in a national sports organization in a country that is enthralled by men’s hockey was and still is a daunting task.

When Peters joined the CAHA, women’s hockey had just moved into the high-performance ranks. Her job description seemed better suited to a small department than to one person: as manager of the national team, she was responsible for producing a newsletter, tracking elite players, and directing all national team selection camps. She also met twice a year with the Female Council, which was comprised of volunteer provincial representatives. In January 1993, after several years at the CAHA, Peters commented on the inequities between male and female hockey. “Women are given a volunteer title and then given absolutely no power and no assistance or authority to do anything with it,” she lamented. “I have seen so many of them frustrated and leaving. That was my first real exposure to that kind of situation. It really opened up my eyes and it’s turned me into a real advocate and a real fighter. It has made me even a bit evangelical about the cause.” Yet Peters also insisted that women’s hockey had come a long way. “Definitely the people that I work with daily at the national level are really quite exceptional in their acceptance of the game,” she said, “and are doing … a great deal to try and help develop women’s hockey. But there’s a huge mass outside of that.”25

That huge mass—including the media, sponsors, male hockey players, the general public, even the agency and its branches—is reluctant to accept the women’s game. Because of this, the support of a national organization is essential to the sport. This is especially so when the sport is the country’s national passion. Given its history and its monopoly over the game, the CHA could play a crucial role in elevating women’s hockey to the same status as the men’s game.

In 1995 the CHA outlined its plans for women’s hockey. It intended to provide more opportunities for women and girls across Canada to play hockey with their peers. It also saw the need for an improved system for player development and easier access for younger players; it also planned to offer specialized training programs for coaches and officials and to create national championships for an increased number of age groups and skill levels. Finally, the association expressed a desire to become more involved with women’s hockey at the international level.26

These plans were and still are commendable but as of 1996 only one new national championship has been added and it is only held every four years. So far very little training is aimed at officials. However, in 1994 a pool of five female coaches was created to train for national team competitions, which is a start in the right direction. The most significant changes in women’s hockey have occurred at the international level (see Chapters 8 and 9). Canada’s leadership at this level can be attributed to several individuals: Frank Libera, former board member of the Female Council and member of the IIHF’s (the International Ice Hockey Federation’s) women’s committee; to a lesser extent Murray Costello, president of the CHA; and most notably Gord Renwick, Canada’s representative at the IIHF. By 1997, the CHA and its provincial partners will have hosted three international events since 1990. If the 1997 qualifying world championship for the Olympics is managed properly, it, too, could help to advance the women’s game by attracting new sponsors and media interest. Only a few other countries have shown any interest in hosting these competitions, so the CHA has shouldered more than its fair share of the responsibility. Yet as the preeminent nation in women’s hockey, Canada is expected to lead the way.

Despite the progress at the international level, the CHA could greatly improve its support of the women’s game at the national level. The overriding influence of pro hockey is another contributing factor. In 1994, a floundering Hockey Canada joined the CAHA. The organization, now called the Canadian Hockey Association, took on Hockey Canada’s former responsibilities, which included managing the senior men’s national team and the International Hockey Centres of Excellence (training centres for coaches and players) in five cities across the country. The addition of new members to the CHA board, such as the National Hockey League and NHL Players Association has served only to cloud the already blurry lines between amateur and pro hockey. The CAHA even deleted the word “amateur” from its name, a term that supposedly defined its mandate. Inherent in the word “amateur” are the values of participation, sportsmanship and the pursuit of excellence; one does not associate the word with the practice of developing future pro stars at the expense of young players. “They are so interconnected, the NHL and CHA,” explains hockey analyst Alan Adams. “[The NHL is] like this locomotive: you ride it or you get out of the way because it will run you over.”27

The NHL dominance in amateur hockey surfaced again in discussions with the IIHF and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1994. At a time when amateur events are fast disappearing, the addition of pro hockey teams to the 1998 Olympics further undermines the amateur ideal. Hockey enthusiasts argue that fans want to see “the best against the best,” which in their eyes means the NHL players. But the NHL’s insertion of “dream teams” into the Olympics means that each country’s regular national team has essentially been jettisoned from the Olympic Games by pro hockey parading under the banner of sport development.

Pro hockeys influence also affects the debate about what the draft age should be for junior male players. This debate has been ongoing since the 1970s. Many parents and coaches have lobbied for it to be raised from eighteen years of age to twenty in order to allow younger kids more time to develop both as players and as individuals. NHL teams, on the other hand, have pushed to sign up young talent sooner so that players can make an early entry into the pro ranks. Male hockey is still coping with these difficulties in the 1990s. “There are some problems with it [male hockey] at all levels,” Glynis Peters acknowledged in 1993. “There are problems in minor hockey of too much pressure on the kids; too much ice time … boys dropping out just because they don’t make the NHL. In the NHL we’ve seen the violence, the checking from behind, the serious injuries, and players being tossed around from team to team.”28

All this has a direct effect on the women’s game. Peters would like to see women’s hockey develop as a distinct game, not one that is trying to emulate the men’s game to gain validity. “In hockey we don’t want to be the same as the men. We don’t want that game,” she insists. “We play a different game and we think that there are values in our game and aspects to our game that should in fact be protected, and, to be quite frank, the men should probably adopt.” But the men’s game persists as the legitimate model, and the lack of appreciation for the female game continues to hinder national development. Women’s hockey still lags years behind men’s in key areas such as the development of female coaches, referees, officials, and volunteers. In order for progress to take place in these areas the CHA must make changes that allow women more control over their own game.

Aware of the paucity of leaders and volunteers, Peters and the Female Council introduced role model workshops in 1995. In 1996 Peters launched leadership seminars to attract and educate new volunteers. But it will take decades for these seminars, which are only held once a year, to develop the volunteer base that is needed to support the women’s game. One obvious way to recruit more volunteers would be to add a women’s hockey coordinator to the staff of each provincial branch of the CHA. These leaders could champion the game in underdeveloped areas such as high schools and universities within the provinces.29

While the decision to include representation from the Female Council on the CHA board in 1982 helped to further the women’s game, the influence of one volunteer female director and one female hockey manager is relatively insignificant given that the forty-five members of the association staff are primarily devoted to male hockey, as are the branch presidents and directors and council representatives. Moreover, many of the volunteers and staff are men who are ex-hockey players or coaches who have little experience with women’s hockey and resent the intrusion of female players into the game. According to Frank Libera, the officer for the women’s high performance committee, “Women’s hockey needs strong advocates on the board. The CHA culture needs work,” he said in 1994. “If an organization wants to change, people have to give up power.”30

In the case of women’s hockey, power also means money. The CHA budget allocates very little to women’s hockey. For the 1994–95 season the CHA’s expenses totalled $8,860,837, of which $210,710, or less than 3 percent, was earmarked for women’s hockey. The total CHA revenue was $8,825,865, which breaks down as follows: federal government grants totalled $1,218,400; the five Centres of Excellence, promotional and training centres sponsored by NHL teams, contributed $450,000; funding agencies contributed $528,200; the rest of the revenue came from sponsorships, gate receipts, advertising, hockey resource centres and various programs and branch revenues. According to the CHA budget, male hockey received $1,171,290 of the government-allocated funds, while women’s hockey received $47,110 or a paltry 3.8 percent of these funds. Moreover, despite the high number of CHA staff members devoted to the male game and the male sport’s aggressive marketing campaign, men’s hockey lost $1,042,662, whereas women’s hockey lost only $139,430 in 1994–5. (Government revenue from these totals was excluded.)

The CHA is reluctant to discuss details of the budget and Peters refuses to even comment on it. The Female Council director, Karen Wallace, justifies the small percentage of federal funds allocated to women’s hockey by arguing that 3.8 percent represents the approximate registration ratio of women’s hockey to men’s. But allocating funds to women’s hockey simply on the basis of registration numbers doesn’t take into account the historical imbalances between the male and female games or redress the fact that the women’s game has been underfunded for the last eighty years. Thousands more young girls would be playing now if they had received the encouragement and the financial support boys get. Even Murray Costello, president of the CHA, acknowledged the association’s shortcomings. “Fifty percent of our Canadian youth have been deprived of a wonderful experience for a long time by reason of us not moving earlier on this,” he said in 1990. “I’m sure there were an awful lot of talented women who could have had that experience [hockey], but didn’t because it was never organized.”31

The success of the women’s senior national championship in increasing the number of players in the senior age category points to the huge gap in opportunities for other age categories. It is indisputable that national championships are important cogs in the development wheel of any sport. Despite the Female Council and the CHA’s involvement with women’s hockey, only one annual national championship exists for women. Moreover, regional competition for women so far has only amounted to an annual Western Shield Senior Championship for the Western provinces. In the East, the Atlantic Shield (formerly the Eastern Shield) was relaunched in 1990, but this championship is not an annual event.

One extremely important area of growth lies at the university level. In 1994 the Canadian Interuniversity Athletic Union (CIAU), the governing body for university-funded

sports in Canada, joined the CHA board. A year later the CIAU, armed with a new equity policy, trumpeted plans to add women’s hockey to its varsity sport roster. At that time almost forty universities reported having women’s hockey teams, but only two provinces, Quebec and Ontario, funded varsity programs. Jennifer Brenning, director of international and community relations for the CIAU, believes women’s hockey could take off as women’s soccer has; women’s soccer has flourished over the past ten years and now has varsity status at Canada’s thirty-six of forty-five universities.32 Not only does becoming a CIAU sport mean more funds for the women’s game, it will also mean access to more ice time. Varsity players practise four or five times per week, which gives them a decided advantage over their club team counterparts, who only practise once a week. In anticipation of a CIAU championship, the universities of Guelph and Windsor added teams to the Ontario Women’s Interuniversity League in 1994. Furthermore, Ontario and Quebec are planning a new regional challenge match between Queen’s University, the University of Toronto, Concordia University, and the University of Quebec, at Trois-Rivières. (The CIAU requires that a sport have three regional conferences before it qualifies as a CIAU championship.)

But recent cuts in government grants to universities and the CIAU have forced both groups to reassess their priorities. Moreover, the CHA’s lukewarm interest in the university game coupled with the lack of effective lobbying by representatives of university women’s hockey makes it unlikely that it will become a CIAU-funded sport in the near future. “There are no champions for the sport [within the universities] and the CHA are not really keen,” says Brenning. “The leadership should come from the bottom up. The CIAU executive were trying to push it from the top down.”33 In May 1996 the CIAU struck an ad hoc committee to develop a proposal for a women’s hockey, participant-funded event that would take place in 1997–98.

Despite the paucity of championships for women, the CHA and its provincial counterparts have endorsed and supported ten annual events for male hockey: three national Junior championships; one Midget championship; three Bantam championships for the East, the West and Ontario, respectively; two Peewee championships, one for Ontario, the other for Atlantic Canada; and a CIAU Athletic Union Cup.34 With the exception of the national senior championship, all of these male championships have sponsors. Lack of sponsorship is often the reason given for not creating more women’s championships. When Shoppers Drug Mart opted out of the national championship in 1987, the CAHA was unable to find another sponsor until 1994. The CAHA said its inability to find a substitute sponsor was due to the fact that the registration figures for women’s hockey were low compared to the numbers for men’s hockey. If one compares numbers alone, women are indeed only a blip on the hockey map: there are 19,050 female players registered versus 493,787 male players. The picture begins to change, however, when one considers the growth rate of the women’s game. Registration in women’s hockey in 1984–85 stood at 5,778 players. In the last decade, that number has more than tripled. And while female registration grew, male registration dropped, from almost half a million players in 1983 to 401,482 players in 1990—a loss of 88,283 players in seven years. In 1992, when women’s hockey gained Olympic status, the 1993–94 registration figure swelled by another 30 percent. In the same year, male hockey lost 57,000 players. Even with only one annual national championship and three world championships under its belt, proportionately speaking the registration figures for women’s hockey have exceeded the figures for the men’s game.

This impressive growth rate, the success of the national team and the new Olympic status led to sponsors such as Imperial Oil signing a CHA sponsorship package in 1995 that at last included female hockey. The three-year contract infuses the women’s national championship with $25,000 a year.35 But sponsorship is only effective in tandem with media coverage. When she was asked in 1993 how long it would take for women players to get the recognition they deserve, Glynis Peters replied with a sigh, “I don’t know. It’s a huge job across the country. The network doesn’t exist. The tools don’t exist. The newsletters [and] the media don’t exist right now to be able to allow these people to communicate and share ideas.” As of 1996, this network still hasn’t materialized, nor has the media coverage, especially in the critical form of television broadcasts. Indeed, neither the CHA nor TSN deemed the final game of the 1996 Pacific Women’s Hockey Championship between the US and Canada—the two leading teams in the world—important enough to broadcast.

Yet the media tools do exist in male hockey. Canadian Hockey Magazine, the annual full-colour CHA magazine, is a product that includes the many factions that drive this amateur organization: pro hockey, national teams, international hockey and national championships. Previously known as Hockey Today, the magazine was launched in 1974 as a vehicle for spreading the CHA message about programs, for attracting sponsors and for merchandising products. The CHA controls the editorial content, which makes up 40 percent of the magazine, and the St. Clair Group sells the advertising, which makes up the remaining 60 percent of the publication and pays for production. The circulation is controlled, which means the magazine is sent to approximately twenty-five thousand coaches, each of whom receives seventeen copies to distribute to his team members. By the end of 1996 the CHA plans to expand Canadian Hockey to three issues a year. Up until this point in the 1990s women’s hockey has been allotted only one article in each issue. These articles are invariably limited to summing up the recent success of the national team or repeating the standard history of the game.

In contrast, the women’s hockey newsletter, Go Overboard, was axed in 1994 when the CHA revamped its newsletter program following its amalgamation with Hockey Canada. The newsletter had been launched only two years earlier. It was the first and only national vehicle for women’s hockey and had received praise from hockey federations around the world. Because women’s hockey has few championships and receives negligible media coverage, the loss of the newsletter cut off a vital national channel of information for players, fans and organizers.

Women’s hockey is trapped in a catch-22 situation that is common to many women’s sports. Lack of support from the national organization has led many people who are involved in women’s hockey to question whether they should continue to work within the traditional male framework. What is needed, some argue, is a separate organization entirely committed to the women’s game. Former marketing director for the CAHA, Larry Skinner is one advocate of more female control. “Women in the game should sell the game. The CHA needs a female technical director who understands and knows women’s hockey,” he says. “The Ontario Women’s Hockey Associations succes’s came from being a separate entity.”36 The OWHA accounts for close to 50 percent of the hockey played in the country. While Ontario has the highest population in the country, OWHA executive director Fran Rider is adamant that the growth of the women’s game is due to its separate organization, which is fully committed to advancing the women’s game.

Peters, however, believes the game must remain within the CHA. “Women’s hockey is an integral part of the Canadian Hockey Association and that’s who’s going to drive it,” she argues. “We’ve gone way beyond ever dreaming or thinking of a separate association.”37 One of the reasons for working within the male framework has to do with federal funding through Sport Canada. The policy concerning separate national organizations for male and female sports has shifted over the years. In its funding decisions, Sport Canada now favours sports organizations that represent both genders rather than only one. It is unlikely that women’s hockey would receive the same federal funding if it was a separate female organization.

For the time being, it is also unlikely that women’s hockey will form its own organization at the national level. Although Canadian women have been playing the game for decades, strong, vocal leaders who will champion women’s hockey are sorely lacking. While Glynis Peters works tirelessly to promote and control the direction of the female game, given her relatively scant resources and the dominant priorities of men’s hockey within the Canadian Hockey Association, her effectiveness is restricted. So, too, is the efficacy of the CHAs Female Council, which possesses little real power. The council meets only twice a year and occupies a subordinate ranking within the CHA hierarchy.

We live in a society that, for the most part, honours and supports boys’ and men’s athletic feats while ignoring those of girls and women. As Richard Gruneau and David Whitson so rightly point out, men have monopolized the physical spaces where sport is played out, effectively transforming arenas into “men’s clubs.” And they have also laid claim to the cultural spaces of sport. This, coupled with the dominance of professional hockey in Canada, leaves little room for the women’s amateur game to flourish. Truly supporting women’s hockey, therefore, means challenging some core beliefs about the role of both men’s and women’s hockey. Is the “win-at-all-costs” mentality really creating winners? Or is it ensuring that large segments of the population, including girls and women, remain outside the game? Until those who support women’s hockey challenge these central assumptions about our national game, women’s hockey will remain in the second-class position it has been stuck in for decades, the “little sister” of Canada’s national sport.