WILLIAM B. EIMICKE

Across India several expansive partnerships are under way to connect citizens with important government services. In return, citizens are receiving high-quality health care and access to bank accounts, which is simultaneously stimulating the economy of India and reducing corruption often referred to as “skimming.” One set of partnerships is widely known as Digital India, a suite of related initiatives to provide every one of India’s more than 1.3 billion residents with a secure identification card through which they can access a national network of public and private services.

The government is working with numerous partners on significant up-front investments in a long-term strategy that will take many years to fully implement. These programs will unlock significant intrinsic value over time by making government more efficient and honest, and by providing citizens with direct access to essential public services. For example, using biometric security, residents can conduct banking and access important personal records, such as proof of identity, voter registration, deeds and permits, driver’s licenses, and automobile registration. All of this can be delivered through a relatively inexpensive smartphone, serving citizens across income levels and from even the most remote rural areas.

Building on these investments, the government is also working closely with the private sector to provide advanced, high-quality health care services to poor and working class citizens. Through cross-sector partnerships, the government is providing residents across India with access to low-cost medical care in clinics and local service centers using the Internet and advanced medical technology and practices. The government is partnering with private programs, such as Apollo Telemedicine, as well as with local entrepreneurs to collaboratively develop a strategic plan and deploy complex programs. This chapter discusses how Digital India and Apollo Telemedicine used a well-structured, highly decentralized process to serve a huge and very diverse population across a country as large as a small continent.

INDIA RISING

Independent since 1947, India is a relatively young democracy established after several centuries of tumultuous relations with Great Britain. Britain effectively ruled large parts of India from 1600 to 1857 through the independent East India Company and directly as a British Colony from 1858 to 1947, a period often referred to as the British Raj.1 Imperialism and colonialism are largely discredited and vilified in the twenty-first century, but the Indian democracy, its well-respected (and frequently criticized) civil service, and even two of its greatest modern leaders, Gandhi and Nehru, were shaped by the experiences of the Raj.2

Today’s India reflects its past as it seeks to transform itself into a leading nation for the twenty-first century.3 India is the world’s second most populous nation, with more than 1.3 billion people, and ranks as the world’s third largest economy.4 The number of very poor people in India is declining, and its ranking in the Gini Index—a ranking of relative inequality—is improving, but it remains a poor country with huge disparity between rich and poor. India’s Gini score (lower is “better” or “more equal,” higher less so) is 35.2 compared to 26.8 for Norway, 45 for the U.S., and 49.7 for Brazil.5 India currently has less income inequality than the United States or Brazil; however, more than 21 percent of the population still lives on $1.90 a day or less.6 Hundreds of millions of Indians remain extremely poor, representing about one-third of the poor in the world.7

There is good reason to be optimistic about India’s future, however. Over the past three decades, India has transformed its agricultural sector, becoming a net exporter of many agricultural products instead of a net importer. India is now the world’s sixth largest net exporter, particularly of rice, cotton, sugar, and beef (buffalo). Its export growth was the highest of any country in recent years, with twice as many exports as the EU-28, and India is second only to the United States in cotton exports.8 India has become a global player in health care, pharmaceuticals, data processing, and space technologies and is a world class “back office” for call centers, credit card processing, legal work, and radiology, among other areas. In addition, India will soon have one of the largest and youngest workforces in the world.9 In 2014, India elected a new prime minister, Narendra Modi, who had great success at the state level using public-private partnerships to jumpstart economic growth and reduce poverty. As prime minister, Modi promised to use the successful state-level techniques at the national government level to integrate public-private partnerships through programs such as Digital India.

DIGITAL INDIA

Building on the groundwork developed by his predecessor Manmohan Singh, Modi developed Digital India, founded on the Aadhaar ID, through which India can deliver an ever-expanding portfolio of complementary services over time—income subsidies for heating and cooking gas, records and record-keeping through DigiLocker, health care through telemedicine, and more to come. Key ingredients of the social value investing framework run consistently throughout the Digital India case. For example, the partnership has a long-term investment strategy—building the country’s broadband network and local services centers, and connecting all citizens to it through Aadhaar. Digital India is unlocking hidden or intrinsic value through programs such as the health partnership with telemedicine. These methods are aligned with the social value investing framework because they integrate local stakeholders in program design and delivery. The programs use local banks to provide a broad range of financial services to even the poorest citizens in the most remote communities through cell phone and smartphone accounts. These networks of organizations provide potentially world class health care for everyone from private companies such as Apollo Hospitals Enterprise Ltd., as well as a full range of work-based benefits such as pay, insurance and pensions, and government services directly to employees and citizens through their mobile devices.

Digital India10 is a series of related initiatives created (or rebranded) in 2014 by Prime Minister Modi that are designed to reinvent the country’s public sector using state of the art information technology.11 Modi’s vision is to transform India into a connected, knowledgeable and information-based society through broadband “highways,” universal access to mobile connectivity, electronic delivery of public services, dramatic expansion of access to quality health care, and banking—even to rural and remote areas—and IT-related employment opportunities (including electronics manufacturing).12 A key element in achieving this vision is Aadhaar,13 a twelve-digit random number identification “card,” or ID, issued by the government’s Unique Identification Authority of India.14

Voluntary and free of cost, any resident of India can obtain a unique Aadhaar number. Security and veracity are ensured by demographic information—name, verified date of birth or declared age, gender, address, optional mobile number, email, and biometric information—that includes all ten fingerprints, two iris scans, and a facial photograph (figure 3.1). Available online, Aadhaar can potentially provide residents with a wide range of services and benefits from virtually any location securely, and with much lower risk of skimming and fraud.15

Figure 3.1 Voluntary biometric registration of Indian citizens at an Aadhaar processing center. Photo by Richard Numeroff, courtesy of SIPA Case Collection.

Proof of identity is an important and long-standing challenge in India, particularly for the poor, in a country of 1.3 billion, mostly Hindu (80 percent) and Muslim (14 percent) but also with significant numbers of Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, and Jains. Between them, Indians speak twenty-two official government-supported languages and live across twenty-nine states and seven territories.16 Many people have insufficient documentation to conduct business, create bank accounts, or access government programs. Many different IDs could be used for individual purposes, but until recently only passports and tax IDs (PAN cards) were widely recognized, and few Indians carry those.17 As recently as 2015, 57 million had passports, 170 million had PAN cards, 600 million had voter ID cards, 150 million had ration cards, and 173 million had driver’s licenses.18

One of the main reasons the Indian government pushed forward with a unique identification card was to combat the problem of “leakage.” This kind of corruption or skimming diverts a portion of government social welfare program benefits, often to ineligible recipients (such as local government officials charging “fees,” tribal leaders, or family members) or through duplicate claims. Government officials estimated suspect beneficiaries amounted to 10 to 15 percent of social welfare, totaling as much as half a billion dollars or more annually.19 A World Bank report in 2015 estimated the potential leakage of savings in one government cash transfer program now covered by Aadhaar at $1 billion annually.20

Aadhaar evolved out of a series of initiatives by the Indian national government to provide its residents with a single, multipurpose, verifiable identification card. This began in 1993 with the Election Commission issuing photo ID cards. In 2003, the government approved the creation of a Multipurpose National Identity Card (MNIC). It wasn’t until 2006 that the government began the pursuit of a unique identification card by executive order through the India Planning Commission. This new initiative overlapped with work of the Registrar General of India on the National Population Register and the issuance of a Multipurpose National Identity Card.21 Then prime minister Dr. Manmohan Singh created a multiagency committee to recommend a plan to align the two related projects.

Based on recommendations of the committee, the government created the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) to be responsible for implementation of Aadhaar.22 The National Population Register (NPR) remained responsible for creation of a national database of all citizens and residents of India under the provisions of the Citizenship Act of 1955. This information is then sent to UIDAI to make sure there is no duplication and UIDAI issues (or documents) the Aadhaar number.23

Despite its visionary appeal, Aadhaar faced substantial opposition for many reasons and from many quarters. There was opposition based on privacy concerns, fear that it would be used to deny government benefits not extend them, and that it would benefit illegal residents/immigrants. Other institutions, particularly NPR, but also Congress, feared a loss of control and authority among each other and vis-à-vis their “customer-citizens.”24

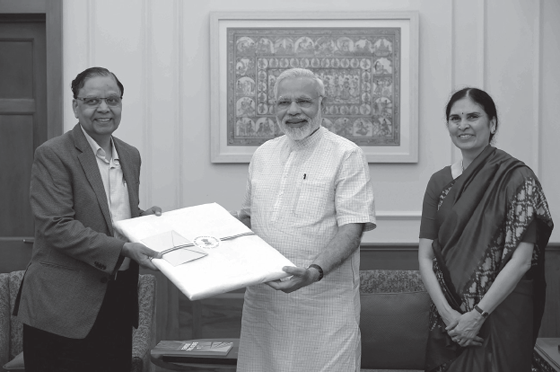

The prospects for Aadhaar changed dramatically for the better when billionaire technology businessman Nandan Nilekani was appointed as UIDAI chair in July 2009 (figure 3.2). He decided to partner with a broad array of private sector partners for everything from infrastructure to more than seventy thousand street-level enrollment contractors. UIDAI partnered with private companies, state governments, banks, and insurance companies to scan biometric data and store it. Even UIDAI management and staff comprised a mix of civil servants and loaned executives from the private sector.25

Figure 3.2 Prime Minister Narendra Modi with Nandan Nilekani, private sector technology business leader recruited to make the Aadhaar partnership a success. Narendramodi.in.

HCL Infosystems Ltd. (HCL), India’s giant computer systems management and outsourcing firm, was chosen to help build and manage Aadhaar’s hardware, networking, and software, beating out international competitors Accenture and Wipro—even IBM and HP dropped out before the final round. HCL would build the central ID repository and manage the database. HCL also ensured Aadhaar was interoperable with existing government systems and emerging new applications in the banking, agriculture, and legal system. Aadhaar staff took responsibility for verification, security, maintenance, and the helpdesk.26

As enrollment increased, the Indian government began to offer programs that worked with Aadhaar members’ IDs. Beginning in late 2012, the national government initiated a cash transfer program linked to Aadhaar for cardholders eligible for cooking gas, food, and fertilizer subsidies. After a successful pilot phase in 2013, the program was made available nationally in 2014. Initial research on the gas program indicated that the more efficient corruption-resistant cash transfers to Aadhaar-linked bank accounts was saving the government between 11 and 14 percent27 (as of 2015, the savings were estimated at $2 billion in this program alone).28 Another study of the cumulative impact of all the subsidy programs converted to cash transfers through the Aadhaar ID bank link was estimated to exceed $11 billion in efficiencies annually.29

Noted economists and India experts Jhagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya strongly support the shift from in-kind benefits. They observed, “Significant gains in efficiency can be achieved by replacing the public distribution system by cash transfers…. The advantage of cash transfers is that they would greatly minimize the leakage along the distribution chain and also eliminate the huge waste that characterizes the public distribution system.”30 Indian governments subsidize a wide range of items—rice, wheat, sugar, water, fertilizer, electricity, rail transport, and cooking gas—so the potential efficiencies and increased welfare to those in need could be tremendous. Leakage in the subsidized kerosene for home lighting program can exceed 40 percent.31 Cumulatively, these subsidies total more than 4 percent of India’s GDP, enough to raise the consumption levels of the nation’s poor above the poverty line if distributed through this more efficient process.32

In addition to the successful partnership process used, Digital India illustrates underlying fundamentals of social value investing: investment in programs over a long-term time horizon that unlock intrinsic social value. These aspects are accelerating Indian’s modernization and helping to raise the standard of living for the world’s largest concentration of people living in poverty. Long-term public infrastructure investments are building a nationwide “digital highway” connecting local service centers, government agencies, and banks to residents through Aadhaar. Once connected, citizens are able to benefit from a new electronic cash transfer system that ensures they receive the full amount of their government program payments, virtually eliminating related corruption. As noted, such a reduction in corruption would have significant impact on the consumption levels of the nation’s poor. The partnership process reflects multiple elements of the social value investing approach by integrating local leadership into program operations and using local banks to provide a broad range of financial services, in turn building community wealth and supporting economic stability and prosperity.

JAM

In 2014 a team from Columbia University visited India to film our case study on these partnerships (figure 3.3). Since that time, the scope and impact of the programs organized under the Digital India umbrella have increased. Social programs tied to Aadhaar are often referred to as JAM—Jan Dhan, Aadhaar, Mobile. Jan Dhan is Modi’s initiative to provide banking services to Indians: accounts, credit, and insurance. Mobile is the cash transfers directly to beneficiaries on their mobile devices. By early 2016, the number of Jan Dhan bank accounts exceeded 210 million, with more than 70 percent actively transacting. Over 170 million are linked to debit cards, and participants are beginning to make their own deposits, apply for loans, and buy insurance.33

Figure 3.3 Prime Minister Modi (center) with economist and Columbia Professor Arvind Panagariya (left). Panagariya served as Modi’s vice chairman for the National Institution for Transforming India, the government agency responsible for Digital India. Photo by AP, courtesy of Arvind Panagariya.

By 2018, the number of Aadhaar IDs issued was over 1,200,000,000,34 and the number of mobile phone subscribers in India exceeded 1 billion, with 350 million of them smartphone users.35 By early 2017, India had become Facebook’s largest market of users.36 Some analysts also see a direct connection between smartphone growth and economic growth.37

Challenges to maximizing the potential of JAM continue. Matching a wide array of national and state means-tested benefits to the eligible Aadhaar cardholders and then connecting those eligible to bank accounts accessible on mobile devices is a work in progress. Extending those bank networks to extremely rural India is also under way but not yet a reality.

In 2015, Prime Minister Modi announced a series of new initiatives to expand Digital India and reach more people in many ways, creating a national digital highway.38 Taken together, the initiatives should make more government services available online, expand connectivity and digital access in rural areas, and expand the nation’s electronics manufacturing sector. In a speech to Silicon Valley technology executives in San Jose, California, in the fall of 2015, Modi said Digital India would make governance “more transparent, accountable, accessible and participative,” and that it would “touch the lives of the weakest, farthest, and the poorest citizens of India and also change the way our nation will live and work.”39

As the communications minister phrased it, “if the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government is remembered for laying down national highways, the Narendra Modi government will be known to have laid the digital highway of the country.”40 Specifics of the initiative included a new data center, eight new software technology parks, and “digital villages” in rural areas that provide telemedicine facilities, virtual classes, and solar-powered Wi-Fi hot spots. More broadly, Modi has pushed to expand access to high-speed Internet connections across much of India.41

The Modi government is also committed to using Aadhaar to make a DigiLocker available to all citizens to safely store important documents such as driver’s license, car registration, education certificates, and deeds. Similar to cloud storage provided by companies such as Microsoft, Apple, and Google, DigiLocker has the twin advantages of being linked to the Aadhaar ID and being protected by multiple levels of security.42 It is easily accessible from a mobile device—no need to hand over a driver’s license or car registration to a police officer or other government official.43 DigiLocker saves documents in PNG, JPEG, and PDF formats so they are easy to share, and it is linked to government services and financial benefit accounts. DigiLocker provides state of the art security measures including 256 Bit SSL encryption, Aadhaar authentication-based document access, hosting an ISO 27001 security certified data center, data redundancy backup, timed log out, external security audits, and data sharing only with explicit consent of the user.44 By early 2018, DigiLocker had 9.5 million registered users, 14 million user uploaded documents, and access to 2 billion other related documents—just a beginning, but a very impressive start.45

Taken together, JAM is following a particular cross-sector partnership process. It has created a system that connects a massive number of users and recipients to essential public and private services over a huge geographic area and uses the best of the private sector’s cutting edge technology as its implementer. As the primary funder, the government provided regulatory authority and expansive financial resources, and each sector engaged a very large number of local entrepreneurs and other stakeholders throughout program delivery.

FIGHTING CORRUPTION

Prime Minister Modi also sees Digital India as a means to fight corruption by putting the competition for public contracts up for bid online, openly and transparently.46 Alleged favoritism in awarded telecommunications and coal licenses by the government prior to Modi’s election are estimated to have cost the taxpayers more than $70 billion.47 Aadhaar protects low-income workers from leakage by local bureaucrats who deduct a “certification and payment fee” typically equal to one-third of the worker’s wages. Under the Digital India innovations, these workers can claim their wages through an app on their cell phone, payable at a local grocery or local center, with a fixed commission equivalent to approximately sixteen cents.48

Digital India is thereby serving the interests of many different stakeholders. It provides a more level playing field for those bidding for government contracts and increases transparency. It also makes government more efficient by helping to ensure that the full amount of income and benefits reach low-income citizens, and it creates an opportunity for many Indians to access banking services for the first time.

BUMPS ALONG THE DIGITAL HIGHWAY

Aadhaar, the linchpin of Digital India, is not without its critics, and there are lingering obstacles to its universality and long-term success. Although well on the way toward universal participation—over 1.1 billion of the country’s 1.2 billion residents registered by the fall 2017—there is currently no strategy to serve those hardest to reach, including millions of homeless people.49 Officially, both the Modi government and the Congress want to require an Aadhaar ID for access to a number of public benefits. But, several Supreme Court decisions have ruled in the special cases before them that an Aadhaar ID cannot be required.

Can biometric data make Aadhaar a unique, reliable identifier? Experiences in the United Kingdom, Australia, France, Argentina, and Kenya indicate that those with medical conditions, the elderly (the iris may change over time), and manual laborers might encounter verification issues.50 UIDAI Director Ram Sewak Sharma told our team in 2015, “experts say our ID can achieve an accuracy level of 99.99 percent. Unfortunately, 0.01 percent off from 1.2 billion is 102,000.”51 Director Sharma went on to say, “from a public policy perspective, even in the current situation where Aadhaar is voluntary, where a large [segment of the] population has Aadhaar, I am left with a much smaller subset to monitor.”52

UIDAI leadership is focused on using Aadhaar to improve the lives of India’s low-income workers and their families and the very poor. At the same time, UIDAI shares the concerns raised by privacy advocates and has therefore resisted information demands from other government agencies, particularly law enforcement organizations. A 2014 Supreme Court ruling decided in favor of UIDAI’s position that it could not be forced to share Aadhaar data without the individual’s consent. The decision also reaffirmed the court’s prior rulings that Aadhaar must remain voluntary.53 Nevertheless, in 2015, a Delhi court ordered that Aadhaar records could be accessed to identify hit-and-run accident victims.54

A large data repository of valuable identity information on more than a billion people poses serious security concerns, particularly in light of the major hacks into large public and private databases all over the world, including the U.S. government’s Office of Personnel Management, Internal Revenue Service, and National Security Administration. Data breaches have also hit the Democratic National Committee, and private sector companies such as Target, Yahoo!, Home Depot, and others. UIDAI has strict policies and multiple protocols to protect Aadhaar and has a good track record so far. Yet, in 2013, the UIDAI Maharashtra office lost the data of 300,000 applicants. Although no evidence of damage has been identified, the affected individuals had to reapply—and faith in the system was shaken. As UIDAI deputy director general Ajay Bhushan Pandey explained to our team in 2015, “people will always find ways to commit fraud with Aadhaar. Nothing is foolproof. There’s always some ingenuity where someone figures out how to game it. But we have given Aadhaar to more than 850 million people and we haven’t come across any significant number of cases where people have been able to beat the system.”55

The Modi government continues to press forward with Aadhaar as a critical interface between citizens and their government. In 2015, public sector businesses such as Air India and the state steel and oil companies were directed to require employees to register for an Aadhaar ID to serve as the basic identification for company attendance, payroll, insurance, and benefit systems.56 As we have seen in numerous examples, public and private databases are vulnerable to criminal and political cyberattacks and government overreach, which present real threats to an individual’s right to privacy. In the case of Aadhaar, it is encouraging to see that the Indian courts have been active in this area to protect the rights and security of all Indians and that the government has worked closely with its corporate partners to maximize the security of the Aadhaar database.

APOLLO TELEMEDICINE: PARTNERING TO BRING QUALITY HEALTH CARE BEYOND THE URBAN CENTERS

Modi still had broad public support in 2018. Although his BJP political party lost some key elections at the state level in 2015 and 2016,57 in early 2017 Modi’s BJP won an important electoral victory in India’s largest state, Uttar Pradesh, dramatically strengthening his political position.58 A Pew Research report found that more than 80 percent of Indians viewed the prime minister favorably, and even a majority of the opposition party members surveyed viewed him positively.59 This widespread popularity is no doubt related to India’s economic growth rate of 7.1 percent for the quarter ending in June 2016 (compared to 6.7 percent for China), making India the fastest-growing large economy in the world.60 And it could well be that Aadhaar and the Digital India infrastructure that the Modi government and its private sector technology partners are building will spur private sector innovation. Furthermore, it will put money directly in the hands of low- and moderate-income Indian consumers to buy the goods and services that the innovation created, thereby growing the economy at an even faster rate.

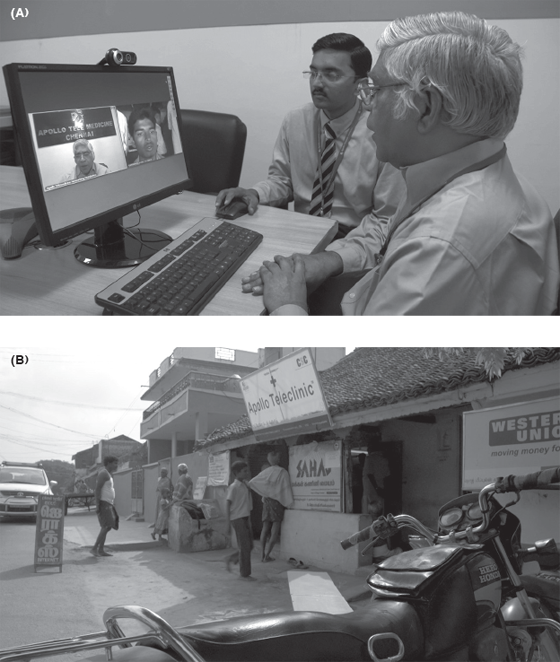

Emerging cross-sector partnerships in India’s public health sector could enhance the societal infrastructure by making what will be one of the largest and youngest workforces in human history healthier and thereby more productive. For example, to advance health care services in the country, the government (through Common Service Centers) partnered with Apollo in 2013. The partnership is aimed at providing state of the art health care to Indians living outside the major cities via telemedicine (figure 3.4).61 Apollo operates a for-profit hospital chain and one of the largest organizations of its kind in the world, with 45 million patients from 121 countries and 9,215 beds across sixty-four hospitals.62

Figure 3.4 (a): Apollo medical experts conduct a remote telemedicine consultation. (b): A village Common Service Center (CSC) where telemedicine consultations are offered to the community. Photos by Richard Numeroff, courtesy of SIPA Case Collection.

Common Service Centers (CSCs) is a division of the central government’s Department of Information and Technology. Created in 2006, CSCs expand the availability of web-based e-governance services throughout the country, particularly to rural areas. Based on a partnership model, CSCs are staffed by Village Level Entrepreneurs (VLEs) and representatives from the national and state government. Services include agriculture information; payment of electric, water, and telephone bills; banking; government forms and certificates; printing; and Internet access.63 The Modi government sees CSCs as a cornerstone of Digital India because they provide access points to every corner of India and to the increasing number of services and assistance the government hopes will create a much more inclusive society and will improve the quality of life for India’s very large population of poor families and individuals.64 Apollo sees the program as an opportunity to do good while simultaneously attracting new customers and perfecting a new way of delivering medical services. The government also hoped to serve the public interest by illustrating how Digital India could help make a real difference in the lives of its most needy and isolated citizens.

Both partners realized that the potential was great but that this initiative was complex and expensive, with a relatively high risk of failure. Apollo built its business by providing high-quality health services to middle-class and wealthy Indians and international patients at a much lower price than U.S. and European providers. As early as 2000, Apollo experimented with telemedicine as a pro bono enterprise serving India’s rural areas using satellite technology provided by the Indian space research organization. Later the Internet, Skype video, electronic records, Bluetooth stethoscopes, and wireless sensors enabled Apollo to expand its market-rate health businesses through tele-radiology and clinics in large housing developments in India, the Middle East, and Africa, totaling more than one hundred centers in twelve countries.65

Developing a telemedicine public health service partnership primarily to serve India’s rural poor is an ongoing challenge. Apollo wanted the enterprise to be a for-profit business with a positive social impact. The government’s CSC leaders envisioned a free, public service. After much discussion, the partners agreed to charge patients a low fee of 100 rupees ($1.60) for primary care and 900 rupees ($14.40) for specialties such as neurology and cardiology.66 The fees are split 40 percent to Apollo, 40 percent to the local Village Level Entrepreneurs that facilitate the examination at the local center, and 20 percent to the government CSC. Even at these very low fee levels, Apollo’s leadership believed the organization could at least break even on the initial service because of the large number of patients. In the long run, they also expect that once access is established and relationships are built, use of services covered by state-subsidized insurance would make telemedicine a viable business in India.67

Indian telemedicine continues to face ongoing technical challenges: unreliable electrical supply, inadequate Internet bandwidth, video distortions, and software malfunctions. Even so, Apollo reports that telemedicine examinations provide reliable diagnoses for 80 percent of patients, including the more complicated neurological and craniological cases. Telemedicine examinations are generally videotaped (with the permission of the patient), providing the physician with an opportunity to review or “see” the patient again several times, to make sure the initial diagnosis was correct and that no important information was missed.68

The prospects for the telemedicine partnership remain bright, but the rollout has taken some time. The program—National Telemedicine Network (NTN)—was officially launched by the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology and Apollo Hospitals on August 25, 2015.69 Initially, services were provided in 60,000 CSCs across the country with a focus on reaching underserved remote regions. The government also announced that the CSCs would collaborate with the Bureau of Pharma PSU of India (BPPI) so that telemedicine patients could order generic drugs online through the CSC network.70

The Modi government’s commitment to telemedicine remains strong in 2018, although it is now supporting a new modified approach to its rollout. The original model begun in 2015 and the CSCs remain in place, but the Indian government has now supported a new project involving 164 eUrban Primary Health Centers in the state of Andra Pradesh. The technology for delivery remains the same as with the CSC model, but each local center is a fully functioning and professionally staffed local community health clinic, rather than a privately run office offering a variety of services. Apollo uses remote telemedicine to deliver expert care from its specialists in the central hospitals, but it can rely on more fully trained local staff for support. The government, whose role in the original CSC model was more limited, is now providing full funding for each center’s operating costs, and Apollo is responsible for all local staffing and service delivery. Remote telemedicine remains a core component of the plan, allowing most services to be delivered by trained registered nurses and telemedicine technicians. As a network of organizations and communities, this initiative has developed into a comprehensive and complex cross-sector partnership providing expansive, world-class health care.

LOOKING FORWARD

Although challenges remain, Indian government telemedicine initiatives clearly show the powerful results of a successful government funded, private-sector operated, and community supported and engaged partnership. There is a convergence of interests between the partners to expand affordable health care to the very poor, sharing the financial risk and potential reward. Each partner is making resource investments and working together to secure a reliable, sustainable revenue stream without pricing anyone out, and they are working to have a greater positive impact on health outcomes for the poor than would be possible without the partnership. They also have a comprehensive strategy for long-term program sustainability, a plan that has been modified several times since Apollo first ventured into telemedicine in 2000.

Achieving financial viability for programs serving the poor is improving as the government expands the number of services covered and develops relationships with health insurance providers. Clearly, long-term investment in building an infrastructure backbone is essential to success, and both the government and Apollo have invested in its construction. In the case of telemedicine, increased involvement by Apollo in the implementation phase has yielded much better results.

For the Digital India and JAM initiatives, government legislation, regulations, and funding have been crucial to progress. Building the infrastructure and implementing and connecting the system to services for residents has been run by private companies. Significantly, Aadhaar’s unique biometric identification system, on which Digital India and JAM rest, achieved a new level of permanence and legitimacy on March 26, 2016, when Lok Sabha (House of the People, the Indian Congress) passed The Aadhaar (Targeted Delivery of Financial and Other Subsidies, Benefits and Services) Act, 2016. The law entitles every resident to obtain an Aadhaar card but does not require it. Any public or private entity can accept the card as proof of identity, but it is not a proof of citizenship or domicile. The law is important because it enables the government to link the card to additional benefits and for banks to use it to eliminate fake accounts.71

In many respects, Digital India, JAM, and Apollo Telemedicine are partnerships that exhibit multiple elements of the social value investing framework. Having the right people has been crucial. Without the leadership of Prime Minister Modi, billionaire technology businessman Nandan Nilekani, and one of Apollo’s leaders, Dr. Krishnan Ganapathy, it is unlikely that Digital India or Apollo Telemedicine would have been nearly as successful as they have been to date. These partnerships illustrate how important the partnership process can be when planning and designing complex cross-sector collaborations.

These examples also exhibit the other elements of the social value investing framework, which we describe in the coming chapters and cases. Numerous organizations made coordinated and tangible investments in individual communities—very much a place-based approach—that were informed by local residents and entrepreneurs. Each partner had something unique and important to contribute, sharing various aspects of risk as well as potential reward from the outcomes of the initiatives—resembling a portfolio strategy. Although program delivery was decentralized and partners came from different sectors, they were able to share success by maximizing the public benefit generated for citizens across India through measurable performance indicators.

In the next chapter we use the cases of Digital India and Apollo Telemedicine to illustrate our cross-sector partnership process. Combined with other’s extensive related research, we include formalized definitions and descriptions of partnership functions and partner roles. We also discuss tools partners can use to assist in comprehensive planning to achieve their shared goals.