Introduction: Used Books

“Mark my words.” So the authors, editors, and printers of English Renaissance texts exhorted their readers; and mark they did, in greater numbers than ever before and more actively, perhaps, than at any time since. Marking was a matter, then as now, of attending to words, listening to their stories, thinking about their arguments, and heeding their lessons. But Renaissance readers also marked texts in the more physical and social senses captured in the phrase “making one’s mark”—making books their own by making marks in and around them and by using them for getting on in the world (as well as preparing for the world to come). Indeed, if the date ranges in the Oxford English Dictionary are to be trusted, the mental connotations of the word “mark” follow on from the material and graphic practices it designated: “To notice or observe” comes after “To put a mark on” and “To record, indicate, inscribe, or portray with a mark, sign, written note, etc.” Among the earliest definitions is “To write a glossarial note or commentary against a word or passage”; this meaning is described as “obsolete” now but it was certainly current throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance and is, in fact, the form of marking that will concern me for much of this book.1

How to Read a Book, Circa 1600

Taking note was often a matter of making notes; and Renaissance readers were not only allowed to write notes in and on their books, they were taught to do so in school.2 Gabriel Harvey’s marginalia (quoted in my preface above) describe the active practices used by one of the period’s most advanced scholars in marking the texts he deemed useful. But from John Brinsley’s Ludus Literarius; or, The Grammar Schoole (1612), one of the period’s most influential handbooks for teaching young students to read and write, it is clear that the same methods—and the language used to describe them—were introduced at an early age:

difficult words, or matters of speciall obseruation, [which] they doe reade in any Author, [should] be marked out; I meane all such words or things as eyther are hard to them in the learning of them, or which are of some speciall excellency, or vse. . . . For the marking of them, to doe it with little lines vnder them, or aboue them, or against such partes of the word wherein the difficulty lieth, or by some prickes, or whatsoeuer letter or marke may best helpe to cal the knowledge of the thing to remembrance. . . . To doe this, to the end that they may oft-times reade ouer these, or examine and meditate of them more seriously, vntill that they be as perfect in them, as in any of the rest of their bookes: for hauing these then haue they all.3

When working with Latin texts, Brinsley suggests that beginning readers should take the time to “note the Declension with a d, ouer the head, and a figure signifying which Declension,” “The Coniugation with a c, and a figure,” and so on. “As they proceede to higher fourmes,” Brinsley continues, they should “marke onely those [things] which haue most difficulty, as Notations, Deriuations, figuratiue Constructions, Tropes, Figures, and the like: and what they feare they cannot remember by a marke, cause them to write those in the Margent in a fine hand, or in some little booke.” These blank notebooks could also be used for compiling glossaries of difficult Latin words,4 as well as for digesting sermons.5

The reason for all this methodical marking—what a printed marginal note signals as “The ends of marking their bookes”—was that the students “shall keepe their Authours, which they haue learned” (140–41). Such annotations are, then, first and foremost an aid to the memory, which is “the reason that you shall [find] the choysest bookes of most great learned men, & the most notablest students, all marked through thus” (46). But in Brinsley’s teaching, the knowledge stored up is not just to be kept in mind but put into use: “Legere & non intellegere negligere est. To read and not to vnderstand what wee read, or not to know how to make vse of it, is nothing else but a neglect of all good learning, and a meere abuse of the means & helps to attaine the same” (42). As in Whitney’s emblem on the scholar Andrew Perne (whose motto reminds us that “The use, not the reading, of books makes us wise”), reading is just part of the process that makes for fruitful interaction with books. Only with marking and practice can books lead us to the kind of understanding needed to make them speak to our present needs.

Appropriately enough, the Huntington Library’s copy of this text has been carefully marked by someone named Thomas Barney. In preparing for his own work in the Renaissance classroom, Barney puts Brinsley’s annotational precepts into action. In the book’s cramped margins, he either summarizes Brinsley’s teaching or expands upon it: for instance, next to Brinsley’s definition of the “phrase” (147), Barney writes, “a phrase is nothing ells but an apt and fitt composeinge and connectinge of words for elegancie and sweettnes of methode or stylle: that it maie be like Orpheus harpe to moue or rauish ye hearers or readers,” and next to Brinsley’s first use of the word “gloss” (176), Barney enters a gloss of his own, “a greco. it signifieth a tongue, alsoe an exposition of a darke speech.” And he uses the blank flyleaves to distill Brinsley’s scattered advice on a number of subjects, including the best methods “for translatinge into latine,” the chief differences between transitive and intransitive verbs, and the most useful texts for teaching young readers, writers, and speakers: “Tullies sentences to teach schollars to make latine purely and to translate into Latine: Apthonius for easie entrance to make Theames for vnderstandinge the matter and order: Drax: for Phrases both english and latine. Flores Poetarum: to learne to versifie ex tempore of anie ordinarie Theame: Tullie de natura deorum for sweet stylle in disputation in the vniuersities. . . . Of all other bookes buy the little booke called the schoole of good Manners, or the new schoolle of vertue for ciuilitie translated out of ffrench./”6 While Barney was concerned with the cultivation of classical eloquence among students who were evidently destined for university and court, the lessons of Whitney and Brinsley applied to the marking of texts for many purposes beyond learning Latin and to readers from all over the socio-professional spectrum. And if those readers were not always as “goal-oriented” as Gabriel Harvey,7 most of them were trained to be mindful, when they picked up a book of almost any kind, of the possible uses it could be made to serve in a range of contexts.

Patterns of Use

Marginalia and other readers’ notes are by no means universal, but they are very common—shockingly so if we are used to working with the clean texts of modern editions, in libraries where writing in books is now forbidden, among readers who are no longer taught why or how they might want to write in their books. Just over 20 percent of the books in the Huntington’s STC collection contain manuscript notes by early readers (not just signatures, underlining, and nonverbal symbols but more or less substantial writing);8 and there are several reasons why the practice must have been much more widespread than that figure suggests.

First, the copies of Renaissance texts that have survived represent only a fraction of those that were produced; and the more heavily a book was used, the more vulnerable it was to decay. The astonishingly low survival rates discovered by Jan van der Stock in his work on the popular prints produced in Antwerp during this period led him to the paradoxical conclusion that “the larger the quantity of impressions made and the larger number of people they reached, the smaller was the chance of the material being preserved.”9 He cites the example of the more than 9,500 prints of St. Ambrose made by the guild of the Antwerp schoolmasters between 1536 and 1585—not one of which survives today—and suggests that they perished

not through indifference, but because they served their purpose. . . . Most devotional prints . . . were simply cherished to destruction. They may have been attached to the inside of a traveling case, or—sometimes cut into smaller sections—pasted to a manuscript. Or they vanished between the cracks of the wooden floor of a monastery church, to be rediscovered centuries later. In a few cases they were cut up and pasted to the wall as decoration. . . . In Bruges some woodcuts were even found pasted to the damp layers of plaster in a crypt. . . . Prints with topical value, such as posters, advertisements, or calendars, were generally simply discarded after a while. . . . Sometimes a print was recycled as lining for a book cover or as the flyleaf in a register of archives. . . . In the Antwerp city archives, a sixteenth-century woodcut advertising the work of a pin-maker was fortuitously preserved, because it spent centuries serving as wrapping paper for the wax seal attached to a document. (174–79)

Printed images and texts were part of a dynamic ecology of use and reuse, leading to transformation and destruction as well as to preservation. And reading, as a form of textual consumption, is not just a producer but also (as Roger Stoddard reminds us) “the eradicator of vital signs. The squeeze and rub of fingers stain and wear away ink and color, fraying paper thin, breaking fibers, and loosening leaves from bindings. Rough hands sunder books, and over time even gentle hands will pull books apart.”10

Second, in the course of these books’ long and varied lives, many later readers (and the binders and sellers who served them) felt no compunction whatsoever about modifying or altogether effacing the marks of earlier readers. In her survey of incunables at the Folger Shakespeare Library, Monique Hulvey pointed out that “The destruction of manuscript annotations reached its peak in the nineteenth century, when printed leaves were washed and bleached in a concerted effort to ‘clean’ the margins of the books, and the edges were cropped as much as possible in rebinding, in order to get rid of all the ‘mutilating’ marks”11 that might make the book less attractive to a new breed of wealthy collectors. Most of the Huntington’s post-1500 items were (fortunately) not considered valuable enough to warrant this special treatment, but no less than 40 percent of the Huntington’s incunables bear evidence of one or both of these methods. While Henry Huntington did not himself express an antipathy to marginalia, the copies in the collectors’ libraries that he bought en bloc tended to be unusually clean—and other (more randomly assembled) collections are likely to have a higher proportion of annotated books.12

And third, by the end of the sixteenth century it had become increasingly common for readers to take their notes in loose-leaf or bound notebooks or erasable writing tables.13 Brinsley’s diligent students, as we have seen, used both marginalia and blank notebooks, but by the middle of the seventeenth century there were signs of a general drift from the former to the latter. Paper remained relatively expensive, and blank notebooks relatively scarce, throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries: indeed, paper accounted for much of the cost of a book—which meant that, unlike today, the scraps of paper most readily available for miscellaneous notes were those that surrounded printed texts.14 But the impact of mass-produced notebooks can be clearly glimpsed in the pictorial encyclopedia of Johannes Amos Comenius (1659): “The Study is a place where a Student, apart from men, sitteth alone, addicted to his Studies, whilst he readeth Books, which being within his reach, he layeth open upon a Desk and picketh all the best things out of them into his own Manual, or marketh them in them with a dash, or a little star, in the Margent.”15 In the illustration for which this text serves as an explanatory caption, Comenius’s ideal student writes in a blank book rather than in the margins of the book (and even if the student were to enter his notes directly in the printed book open before him, Comenius assumes that he would need margins only wide enough for the simplest of symbols).

Once I opened my eyes to them, I discovered that the margins of Renaissance books were teeming with the traces left behind by actual readers. My experience was comparable to that of the medievalist John Dagenais, who, turning to manuscripts after years of working with pristine modern books, found texts that “had rough edges, not the clean, carefully pruned lines of critical editions; . . . edges . . . filled with dialogue about the text—glosses, marginal notes, pointing hands, illuminations . . . activities by which medieval people transformed one manuscript into another.”16 Dagenais’ terms, I would suggest, should be extended to the texts of early print culture: Renaissance readers regularly transformed one printed book into another,17 and, indeed, they occasionally turned one back into a medieval manuscript (as in the case of the “Uncommon Book of Common Prayer” discussed in Chapter 5). Looked at from the user’s rather than the producer’s perspective, there are significant continuities across the “Medieval-Renaissance” divide—not only in the visual forms of books but in the transformative techniques employed by their readers.18 Some preprint practices passed to readers in the age of print (including rubrication, or the use of curly brackets in the margin, decorated with foliage or transformed into portraits in profile) and no doubt helped them come to terms with the new medium by marking its products with traditional features. Other practices traveled from scribal culture into typographic and even digital culture, such as the pointing hand which few of us still use in our marginal notes but which has survived as a typographic symbol that can now be produced by most word processing programs. Another scribal tradition that enjoyed a surprisingly rich afterlife was the “anathema” (or book curse) that owners inscribed on their books to prevent them from being lost or stolen.19 Even well into the seventeenth century, owners of books were adding such curses to their signatures: on the last page of a 1639 Psalter at the Huntington we find,

To Stephen Dance this book belong

and he that steale it dowth him rong

lev it alone and pase there by

in euery place where it doth lye,20

while the owner of Thomas Blundeville’s 1613 Exercises was more aggressive, warning “hee that douth this bouke stayll hee shall be hanged.”21

Looking at Renaissance marginalia from the end of the period, in fact, we find that these transformative manuscript marks do not die away as quickly as our most authoritative narratives would have us believe. As printed books gradually freed themselves from the visual and organizational models of the manuscript tradition, William Slights has shown that the use of the margins for authorial or editorial annotations increased steadily.22 And since many of these notes provided the kinds of apparatus that readers were used to writing in for themselves, scholars have assumed that manuscript marginalia decreased proportionally. In their landmark essay on fifteenth-century reading habits, Paul Saenger and Michael Heinlen argued that in the first few decades of printing, books still contained enough in the way of illuminations, rubrications, and annotations that they deserve to be catalogued as if they were manuscripts. But by the second decade of the sixteenth century, they claim, this was no longer the case: “The printer’s provision of all the aids that previously had been added [by hand] . . . effected the final step in the transformation of reading. In antiquity reading had implied an active role in the reception of the text. . . . Throughout the Middle Ages readers, even long after a book had been confected, felt free to clarify its meaning through the addition of . . . marginalia. Under the influence of printing, reading became increasingly an activity of the passive reception of a text that was inherently clear and unambiguous.”23 Adrian Johns has recently cast doubt on whether the texts that printers produced were ever “inherently clear and unambiguous” (at least during the hand-press period): in his account, readers were still learning to trust printed books throughout the seventeenth century.24 Marginalia in surviving books cast further doubt on whether reading became “an activity of passive reception” at any point in the sixteenth century. While the average proportion of annotated books from the incunable period is very high (between 60 and 70 percent), it is not much lower a full century later: among the Huntington’s books printed as late as the 1590s, 52 percent still contain contemporary marginalia. While the numbers do decline after that date (before picking up again in and after the English Civil War25), the proportion for some subjects—such as religious polemics and practical guides to law, medicine, and estate management—remains well over 50 percent for the entire STC period. The evidence left in English Renaissance books suggests that readers continued to add to texts—centuries rather than decades after the invention of printing—and that printed books did not contain everything that every reader needed to make sense of (and with) their texts.

The addition of personalized indexes and tables of contents to books that already included them provides clear evidence (throughout the STC period) that authors and their printers were not providing everything individual readers needed to serve their specific purposes.26 In Chapter 7 we will examine Sir Julius Caesar’s additions to John Foxe’s already massive index to his apparently comprehensive commonplace book—first by writing in new entries alongside Foxe’s printed list and then by adding two new manuscript indexes of his own. This is only the most elaborate of examples, and the Huntington’s books are full of expanded indexes and small lists of key words with page numbers on title pages, flyleaves, and pastedowns.

The most striking indication that printing did not automatically, or immediately, render readers passive is the survival of what might be described as radically customized copies—copies, that is, where the text is not just annotated but physically altered, sometimes even cut up and combined with other texts. There is evidence of reading so active and appropriative that it challenges the integrity of the entire printed book.27 Readers could actively alter their books (when they were bound or rebound) by inserting blank leaves for extensive marginalia, by rearranging the sections, or even by combining sections from different texts.28 In 1673, for instance, a reader signing himself only “GF” filled the margins of a 1638 textbook on mathematics with a running summary of the principles of geometry and inserted several diagrams cut out of other books.29 In more extreme cases, the results make it difficult to identify which is the primary text that is being added to: in the Huntington volume which is catalogued as John Bate’s Mysteries of Nature, and Art, all that remains of Bate’s text is the third of its four books.30 In the place of books 1 and 2 are large sections of books 1 and 2 of Henry Peacham’s Gentleman’s Exercise, while book 4 is replaced by nine pages of manuscript notes—turning Bate’s encyclopedic text into a narrowly focused anthology on drawing and painting.

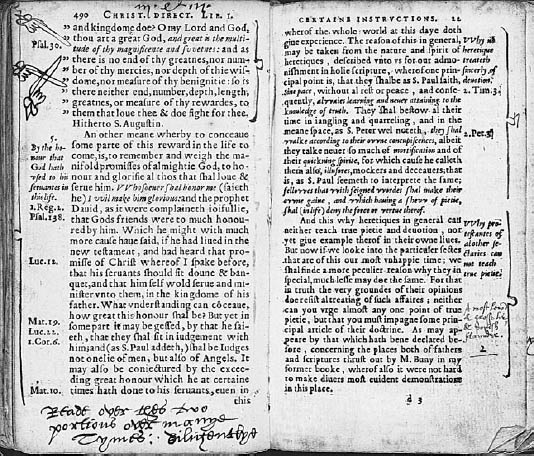

Even when books remained integral and isolated, they could be put to dramatically divergent uses. Many students of reading—including Stanley Fish and Roger Chartier—have wrestled with the fact that the same text can be interpreted or used in radically different ways,31 and there are two ways to comb the margins for evidence of this phenomenon. Sometimes a single copy of a single text preserves the contrasting responses of multiple readers—and one such case is the Huntington Library’s copy of A Christian Directory, published in 1585 by the English Jesuit Robert Parsons (Figure 4).32 This text generated both pro- and anti-Catholic responses, but the Huntington’s copy records voices from both camps within the covers of a single book. One sympathetic reader has written such sober endorsements as, “Reade over thes two portions over [sic] manye Tymes: diligentlye,” often accompanied by ostentatious hands with pointing fingers. A different hand registers the outrage of an obviously Protestant reader with such comments as “A most lewd & grosse lie, & popish slander.”

The other method is to examine multiple copies of a single book. In her survey of some 150 early copies of Sidney’s Arcadia, Heidi Brayman Hackel discovered an astonishing array of early readers’ marks in no less than 70 percent of the copies, “ranging from signatures to a few stray scribbles to elaborate polyglot marginalia and indices.” The range of marks is representative of the entire archive of Renaissance marks, the only surprise being that it is found in a work of literature:

Fragments of verse, lists of clothing, enigmatic phrases, incomplete calculations, sassy records of ownership: some of these traces merely puzzle. Drawings and doodlings in other copies hint at other associations or preoccupations: a shield painted in watercolors, impish faces peering out from the margin, geometric figures on a flyleaf, a mother and child on a blank sheet. Pens are not the only objects that have left impressions in these books; pressed flowers survive in two volumes, and the rust outlines of pairs of scissors [in] two other copies. . . . Fifty-six percent of the books carry marginalia or scribblings on flyleaves, most commonly in the form of penmanship practice, emendations, underlinings, and finding notes.33

On a much smaller scale, I have been recording the marginalia found in multiple copies of the first (1605) edition of Francis Bacon’s Advancement of Learning.34 It is fitting that this text, which advocated the active digestion and application of books, preserves many signs of engaged reading, culminating in the example of Sir William Drake, who cut out pages from his already annotated copies of The Advancement of Learning and pasted them into two of his commonplace books (now at the University of London Library).35 Of the six copies at the Folger Library, three have significant marginalia by early readers. Copy 6 has only a few notes, and they present us with a reader who looks for exactly what we would expect a Renaissance reader of the author of England’s best essays to look for: on sig. Ii3v, next to Bacon’s passage, “We come therefore now to that knowledge, whereunto the ancient Oracle directeth vs, which is, the knowledge of our selues,” the reader has repeated “knowledge of oure selues” in the margin. Copy 5 has the same passage marked with the same phrase repeated in the margin, some rhetorical figures identified, and an extremely efficient set of running summaries in the margins. Copy 3, however, is heavily annotated by a much more resistant reader—his identity is not yet known, but references in the marginalia place him in Oxford around 1615 (quite possibly in the faculty of divinity).36 The tenor of his comments is clear from the outset, where he bridles at Bacon’s effusive dedicatory epistle to King James. When Bacon claims that “there hath not beene since Christs time any King or temporall Monarch, which hath been so learned in all literature & erudition, diuine & humane,” the reader lists three English kings “since ye Norman conquest [who] were excellent Scholers” (A3v); and where Bacon credits the King with knowing all things, our reader interjects, “Perhyperbolen. And indeed ye opinion is foolish. For all things cannot be knowen by creatures . . .” (A2v). Finally, Bacon’s praise of James for his virtue and fortune rather than his religion provokes a pious marginal note: “Faith is forgotten; which is ye chiefe intellectual & gives life & forme of true goodness to all other intellectuals” (A3r).

Figure 4. Dueling marginalia in a single copy of a popular Catholic text by Robert Parsons (1585, RB433864). By permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

When Bacon notes “That if all Sciences were lost, they [could] be found in Virgill,” our reader wryly responds, “Very superficially, forsooth” (K3v). More seriously, this reader’s marginalia regularly take Bacon to task for being a superficial student of Aristotle. On sig. Ff4v, Bacon’s critique is condemned as “grosse sclander,” and on the following pages the reader mounts a spirited defense of Aristotle: “This againe is idle” (Gg2v), “not deserved . . . he being full of inkhorne terms to little purpose” (Gg3r), “But Aristotle is againe wrongd” (Ii2v), and “1. Sense. 2. History. 3. Induction. 4. Universall experience are ye foure instruments of Invention taught by Aristotle & knowen unto most men, & forgotten by this otherwise very worthy knight” (Nn1v). And where Bacon wonders why Aristotle “shoulde haue written diuers volumes of Ethiques, and neuer handled the affections,” our reader wonders again about Bacon’s apparent amnesia: “The honourable knight hath forgotten ye sixt booke of ye Ethicks & ye third booke of ye same Aristotle de anima. . . . And Thomas of Aquin in ye morall part of his Summa Theologica. . . . He hath forgotten also what Tully besides his scattering discourses, hath . . . written in ye .4. booke of his Tusculan questions. He hath forgotten Scaliger & many others” (Xx4v). Most seriously of all, he accuses Bacon of being a secret follower of Machiavelli.37

When we come to Bacon’s famous praise of “fained [or fictional] historie,” we fully expect our reader to record a dissenting view—though not, perhaps, to go so far as to side with Plato in calling for poets to be banished from the republic. Bacon follows Sir Philip Sidney in finding fiction a better teacher than history: “Euents of true Historie, haue not that Magnitude, which satisfieth the minde of Man; Poesie faineth Acts and Euents Greater and more Heroicall” (Ee2r). For our sober reader, however, “it is madnes to seeke satisfaction in falshood. . . . This, I say, is not onely madnes but wickednes. And therefore if poesie have no better end: poets had better be idle then ill occupied, & Plato did well to shut his citie gates against them.” But he saves his fiercest and most extended outburst for the final section, where Bacon excuses himself for not covering matters of divinity because (he feels) that topic has been exhaustively handled by others. The reader begs to differ and drafts an outline of the subjects the section should have addressed: “But surely great unsufficiencie both in ye Methodicall & Solute Theologie, to use his owne uncouth monasticall termes; is yet in the writings of both ancient & moderne authors of Divinity. Who hath written sufficiently of ye 1. Applying of ye meritive & redemptive Theandricke obedience? 2. Of mariage? 3. Of oathes? 4. Of Fasting? 5 Of ye Autonomie of ye church? 6. Of callings?”

One final copy of the same text from the Huntington Library preserves the annotations of a reader who was much closer to Bacon’s wavelength. They are the work of the Genevan scholar Isaac Casaubon, perhaps the finest philologist of his day.38 Here, then, is an encounter between two of Europe’s most celebrated scholars, in the margins of a work that is itself concerned with the management and application of information. Casaubon marked up the book in his usual scholarly fashion (Figure 5). At the bottom of the page reproduced here he has transcribed a lengthy passage from another work (by the Greek orator Themistius) that praised the ruler in terms similar to those contained in Bacon’s address to King James. We can also find him translating some of Bacon’s English phrases into Latin and Greek (across from “wisest,” for example, he has written “Sapientiss.”) and labelling rhetorical devices (next to Bacon’s “And as the Scripture sayth of the wisest King: That his heart was as the sands of the Sea,” Casaubon has written “Cor Regis Simile [a simile for the king’s heart]”). But alongside these standard philological techniques there is a more original and enigmatic practice: Casaubon has marked (or had someone mark for him) the accented syllable of every word with more than one syllable, suggesting that he read it aloud and used the text, at least in part, to practice his pronunciation of English.39

Figure 5. Isaac Casaubon reads Francis Bacon’s Advancement of Learning (1605, RB56251) for English practice. By permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Following Rules in Unpredictable Ways

Such examples capture the challenge of extrapolating general taxonomies of readerly behavior from the traces of interaction preserved in the margins of Renaissance books. Marginalia rarely speak directly to the questions we most want answered, and often reveal a different side of a reader we thought we knew. Another case in point is Barnabe Barnes’s annotated copy of Machiavelli’s Il principe, now at York Minster Library.40 After Christopher Marlowe, Barnes was Elizabethan England’s most infamous invoker of Machiavelli: his play The Devil’s Charter (1607) featured a cast of depraved Italians motivated by Machiavellian precepts, and his meditation on Cicero’s De officiis (published the year before and dedicated to King James) offered a scathing commentary on both The Discourses and The Prince—calling the latter a “puddle of princely policies” and in several places quoting directly from named chapters. His comments in the margins of his Prince are surprisingly spare, stopping well short of the sections cited in his Four Books of Offices, and they are disappointingly restrained in their tone.41 Barnes picks out one of Machiavelli’s most controversial passages (in which he argues that necessary “cruelties are well used . . . that are carried out in a single stroke”), but marks it only with a marginal flower, the conventional symbol for quotability.42 Most of his marginal notes simply translate key words from Italian into English or Latin, and his most emphatic markings highlight an enigmatic passage that seems to refer more to textual interpretation than to the kind of political manipulation for which Machiavelli was notorious: “through the great length and continuity of [a prince’s] dominion, the memories and causes of innovations die out, because one change always leaves indentations for the constructions of another [lascia l’addentellato per l’edificatione dell’altra]” (Bondanella, 8).

Many of the notes left behind by readers bear no discernable relationship whatsoever to the texts they accompany. In his survey of marginalia in medieval and Renaissance copies of Piers Plowman, Carl James Grindley found three categories of notes: the first “are without any identifiable context,” the second “exist within a context associated with that of the [book],” and only the third are “directly associated with the various texts that the [volume] contains.”43 The blank spaces of Renaissance books were used to record not just comments on the text but penmanship exercises, prayers, recipes, popular poetry, drafts of letters, mathematical calculations, shopping lists, and other glimpses of the world in which they circulated—and this is not only true of almanacs, which were the most conventional repositories for this sort of information.44 The Huntington’s copy of Boccaccio’s Amorous Fiammetta contains only one manuscript note: on the verso of the title page an early owner has inscribed a recipe for a leek and herb sauce.45 And in a copy of Erasmus’s De copia, the only note written by its owner, William Anderson, records that “On the 18th of May anno Domini 1585 there was heard a great terrible thundering.”46

But for all of their unpredictability, Renaissance readers usually offer indications of the kinds of training and equipment they brought to bear on their encounters with texts, and the kinds of interests and needs they could be made to serve. Elaine Whitaker suggests that

although readers’ alterations are idiosyncratic, they fall broadly into the following scheme:

I. |

Editing |

|

A. Censorship |

|

B. Affirmation |

II. |

Interaction |

|

A. Devotional Use |

|

B. Social Critique |

III. |

Avoidance |

|

A. Doodling |

|

B. Daydreaming.47 |

In elaborating upon his three types of typical marginalia (mentioned above), Carl James Grindley has proposed a much more elaborate scheme. Within the category of marks with no identifiable context he includes “Ownership Marks,” “Doodles,” “Pen Trials,” and “Sample Texts”; among those notes with an oblique relationship to the books that contain them he includes “Copied Letterforms,” “Copied Illuminations,” “Copied Passages,” “Additional Texts,” “Marks of Attribution,” “Tables of Content,” “Introductory Materials,” and “Construction Marks”; and (most usefully of all) he divides the marginalia that constitute “a coherent reader response to a particular text” into the following categories:

I. |

Narrative Reading Aids |

|

A. Topic |

|

B. Source |

|

C. Citation |

|

D. Dramatis Personae |

|

E. Rhetorical Device |

|

F. Additional Information |

|

G. Translation |

|

H. Summation |

|

|

|

2. Paraphrased Marginal Rubrics |

|

3. Condensed Overviews |

|

4. Textual Extrapolations |

II. |

Ethical Pointers |

|

A. Preceptive Points |

|

B. Exemplifications |

|

C. Exhortations |

|

D. Revelatory Annotations |

|

E. Orative Annotations |

|

F. Disputative Annotations |

III. |

Polemical Responses |

|

A. Social Comment |

|

B. Ecclesiastical Comment |

|

C. Political Comment |

IV. |

Literary Responses |

|

A. Reader Participation |

|

B. Humour and Irony |

|

C. Allegory and Imagery |

|

D. Language Issues |

V. |

Graphical Responses |

|

A. Illuminations |

|

B. Initials |

|

C. Punctuation |

|

D. Iconography48 |

Conventional practices are evident in even the humblest examples, such as the notes found on the blank verso of the final page of the Huntington’s copy of The Treasury of Amadis of France (a popular collection of speeches and letters).49 At least two early readers have completely filled the page with scribbles, penmanship exercises, and a set of surprisingly complex notes of ownership (Figure 6). A long note at the top reads, “Thomas Shardelowe ow[n]eth this book God geue him grace on it to look[.] if I it lose and you it find I pray you be not so vnkind but geue to me my booke againe and I will please you for yor payne[.] the rose is read the leafe is grene God preserue our noble king and queene but as for the Pope God send him a rope and a figge for the King of spayne.” Lower down the page, another reader has drafted a series of phrases from which an ownership formula finally emerges: “Be it knowne Dale Heaver,” “Dale Havers oweth me he is my veri,” “Dale Havers oweth me he is . . . Dale Havers oweth me,” and, finally, “Dale Havers oweth me/ he is my veri tenet [owner] / and I this booke confesse to be/ quicunque me invenit [whoever finds me].” These notes may not do much to acquaint us with Shardelowe or Havers, and they offer next to nothing about their interpretation of this particular text, but they do preserve a human presence that makes this copy unique.50 More important, they allow us to excavate some of the textual formulae—which must have circulated, formally or informally51—available to Renaissance readers for displaying their property, handwriting, and political allegiances.

As this relatively simple illustration suggests, marginalia provide some wonderfully literal examples of the way in which a book must be understood (in Natalie Zemon Davis’s words) “not merely as a source for ideas and images, but as a carrier of relationships.”52 It is not unusual, for instance, to find the phrase et amicorum (and friends) accompanying a signature on a Renaissance title page or binding and several generations of family histories inscribed on flyleaves or pastedowns—as we shall see in several chapters below (and not just the one dedicated to Bibles, with which such notes now tend to be associated). And complex relationships of friendship and patronage were captured by the inscriptions on books given as gifts.53

Marginalia sometimes record a general judgment, such as that offered by Frances Wolfreston in the Huntington Library’s copy of Shakerley Marmion’s play A Fine Companion (1633). Beneath the list of dramatis personae she wrote, “A resnabell prity bouk of a usurer and his 2 daughters and their loves with other pithy pasiges.”54 At times such judgments could be more politically pointed (as in a compilation containing Edmund Spenser’s View of the Present State of Ireland, where a reader has remarked that “the Rebellion of Oct[ober] 23. 1641 justified Spencers wisedome and deep insight into that barbarous nation”)55 or more consequential (as in a collection of medical recipes, where a reader has deleted many passages, noting that “All theas receiptes ar verye falsly written. but being corrected heer they ar trew”).56

Marginalia can identify other texts a reader associated with or even read alongside a particular book. Cross-references and passages copied verbatim from other books are frequent enough to attest to the widespread practice of what has been called “extensive” rather than “intensive” reading and to suggest that (for some groups of readers at least) this mode started in England well before what Robert DeMaria has called the “reading revolution” of the eighteenth century.57 While we might expect readers from the legal profession to have knowledge of and access to a wide range of statutes and precedents, it is striking how often readers of sermons, herbals, or husbandry manuals were able to reference other books and authors in their reading.

Only with a much more comprehensive survey of marginalia in surviving books will statistical patterns become more reliable: at present, the findings in one collection have a disturbing habit of contradicting those in another. For instance, my survey of Renaissance books at the Huntington revealed a clearly marked preference (among marginal annotators) for larger books: marginalia were more than twice as likely to appear in folios than in quartos and smaller-format books. We might expect this to be the case across the board for the simple reason that larger books tended to provide the reader with larger margins in which to exercise their pens. At Archbishop Parker’s library in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, however, the opposite turned out to be true: Parker’s marginalia are much sparser in his folios, and generally hone in on one point or section rather than digesting the entire text. In fact, there are significant differences between Parker’s habits of use in the two classes of printed books: not a single one of his folios has the characteristic monogram he devised for inscribing his initials on title pages, or the cramped summaries that are so common on the flyleaves in his smaller books (as well as his manuscripts). So we are left with the unexpected impression that—at least as a reader—Parker may have drawn a sharper distinction between big printed books and small printed books than he did between printed books and manuscripts.

Figure 6. Ownership inscriptions in The Treasury of Amadis of France (1572?, RB12924). By permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

In scholarly circles, “marginalia” has become the standard term for the notes (both written and printed) that accompany the text in many of the books (both written and printed) that come down to us from the English Renaissance. But it was not the standard term in the Renaissance itself—at least not in English. When George Joye published his response to William Tyndale on the subject of biblical translation in 1535, he concentrated on what he described as “scholias, notis, and gloses in the margent.”58 “Marginall notes” or “notes in the margent” are common enough in the period’s prose; but “marginalia” itself is very rare. While the word appears in neo-Latin texts from the sixteenth century (if not earlier), it does not seem to have entered the English language until the nineteenth century. The OED’s earliest citation is a letter from Samuel Taylor Coleridge dated 22 April 1832, in which he proposed “A facsimile of John Asgill’s tracts with a life and copious notes, to which I would affix Postilla et Marginalia.”59 Coleridge’s use of the term here is clearly Latin rather than English, which undermines its value for the OED’s attempt to fix a precise point of origin. But according to H. J. Jackson’s recent account, Coleridge had already made it an English word—and an English literary genre—when his “marginalia” were published under that label in 1819 (and he would be followed, in the ensuing decades, by Edgar Allan Poe, John Keats, Hester Thrale Piozzi, William Blake, Mark Twain, Herman Melville, Charles Darwin, and others—though some of these authors used the term loosely to gather their miscellaneous observations, whether or not they had their source in marginal annotations).60

The term becomes fixed, oddly enough, just as the practice it describes begins to wane—or rather to be narrowed into an increasingly privileged form of writerly behavior on the one hand, and an increasingly transgressive form of readerly behavior on the other. What were notes for and by readers called in late medieval and Renaissance England, where both the practice of writing in books and the terms for describing it were so wide-ranging? And what do we gain and lose by joining Coleridge (and Jackson) in settling on “marginalia” instead of following Joye in using “scholias,” “notis,” “gloses,” or any of the other terms preferred by his contemporaries?

There is something to be said, to be sure, for standardized terminology. A shared vocabulary is not only useful for research but to some extent necessary for all communication—particularly for that basic task (traditionally performed by titles and indexes in scholarly writing) of ensuring that your reader or auditor knows what it is that you will be discussing. And common terms are important, perhaps even essential, for the process of discipline formation: “marginalia” has played a central role in establishing the emerging field of the history of reading as a legitimate pursuit, with shared objects of study. As Bernard M. Rosenthal has observed, “we can say with some assurance that the ‘incubation period’ for this new and broader interest in manuscript annotations began independently in the minds of a number of people in the 1960s and that by the end of the 1990s it has emerged as a recognized field of study. For better or worse, the informality and improvisation which has marked the beginnings will have to yield to guidelines, definitions and an acceptable nomenclature.”61 Rosenthal goes on to propose the adoption of a particular term in common use in Italy, though whether or not it proves acceptable in the English-speaking world only time will tell: for printed books with handwritten annotations—traditionally catalogued as “libri impressi cum notis manuscriptis” (Curt Bühler) or “books with manuscript notes” (Robin Alston)—he suggests that we follow Giuseppe Frasso and his colleagues in calling them “postillati.”62

The OED describes “postil” as “Now only Hist[oric]”, and there is something decidedly antique about the term. Its primary meaning is indeed that of a “marginal note or commentary” upon a text—but it was used as often for printed records of writing as for manuscript traces of reading.63 Furthermore, it was associated from the start with the explication of the Scriptures, particularly the Gospels; and in most of the many titles it appears in during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the context is explicitly religious. Indeed, in many cases it becomes a form of writing that is closer to a sermon than an annotation: the OED’s most specialized definition is “an expository discourse or homily upon the Gospel or Epistle for the day, read or intended to be read in the church service,” and many of the published “postils” of the period were collections of such texts penned and delivered by famous churchmen.

Likewise, “scholia” was used to signify an “explanatory note or comment” in general, but in most cases it involved an ancient text—either “an ancient exegetical note” or a “comment upon a passage in a Greek or Latin author.”64 “Postils” and “scholia” could be used for pious and learned notes on the Bible or Homer, say, but would they have been appropriate for comments on Shakespeare or (for that matter) genealogical notes in a family Bible? Part of the charge in E. K.’s beguiling scholia in Spenser’s Shepheardes Calendar (1579) comes from what William Slights calls the “intriguing discontinuities between amorous pastoral poetry and the depoeticizing glosses.”65

Spenser’s annotated eclogues offer up a third—and much more familiar—term for “comment, explanation, interpretation”: “gloss.” Evolving in the sixteenth century from the earlier form “gloze,” the word shared the same associations with canonical texts as “postil” and “scholia,” but its applications came to suggest the narrower activity of explaining an obscure word in the text—hence its extension beyond the margins of books to the explanatory entries in glossaries or dictionaries. At the same time, however, it carried with it what the OED describes as “a sinister sense,” implying that the interpretation being offered was “sophistical or disingenuous.”66 As William Slights and Evelyn Tribble have shown (and as I will explore in more detail in Chapter 4 below), glosses on the Bible were particularly suspect, and the authorities fought a losing battle to contain the contestation of meanings that accompanied successive translations of the scripture.67

In the terminology itself, then, we can already find intimations of an antagonistic relationship between the reader and the text, an awareness of the gap between the author’s words on the page and the meaning particular readers want to derive from them. This sense emerges even more strongly in the history of the use of “adversaria,” another early seventeenth-century word for “collections of miscellaneous remarks or observations, = MISCELLANEA; also commentaries or notes on a text or writing.”68 The term derives from the Latin term for “against” or “facing,” and it strictly refers to the location of notes (on the side of the paper facing us or in the space next to the text being annotated) rather than their character. For Nicolas Barker, this points to the “ancient and compelling example” of the page layout employed by classical and medieval glossators, “never far from the imagination and habits of those who adorned and disfigured the margins of later printed books.”69 But recent scholarship has inevitably found in “adversaria” the more common sense of “adversarial”—not just opposite, that is, but oppositional. In the sixteenth century another term emerged, carrying precisely this sense of critical (often censorious) commentary: “animadversion.” This critical spirit is also conveyed by the common emphasis on structures of argumentation in the notes of Renaissance readers (particularly but not exclusively in rhetorical, philosophical, and religious works). Readers who used marginal notes and tables to simplify or clarify the structure of the text routinely focused on disagreements or “doubts” and their “resolutions.”

All of these terms could be grouped under the general heading of “annotations”: to study them is to examine what the classic collection Annotation and Its Texts describes as “the play of note against text.”70 All of these words (including, perhaps, “marginalia”—at least in its strictest sense) define a body of writing that not only accompanies a text but directly engages with it. But as we have already seen (and will continue to see in most of the chapters that follow), by no means all of the interesting notes written by readers in the margins and other blank spaces of books comment directly or indirectly on the text they are found in. Many of the notes that readers wrote in their books—doodles, pen practices, ownership formulae, and a wide variety of quotidian marks that were entered in books simply because they offered a convenient space for writing and archiving—do not qualify as “annotations.” Are students of marginalia and readers’ marks supposed to study these inscriptions and, if so, how are they to be described and approached?

In a sense, they are “graffiti” of the (not necessarily derogatory) sort described by Juliet Fleming. Fleming argues that writing was not contained by the page in early modern England, with “posies” and other inscriptions appearing on walls, rings, and pots; but these texts were also inscribed, in a similar spirit, in the blank spaces of texts.71 Her observations—that “I was here” is “the graffito’s most simple and paradigmatic instance” (72), and that “the prohibition against writing on the interior walls of a house is now deeply internalized” (30)—are repeated almost verbatim in Heather Jackson’s study of marginalia, and modern readers who prefer clean books often use the term “graffiti” to deride other readers’ marginalia.

A less loaded term (indeed, a potentially boring one) is suggested by the subfield of classical archaeology that studies “epigraphs”—what the subtitle of one recent collection describes as “Ancient history from inscriptions.”72 By the early seventeenth century—just as English scholars were beginning to develop tastes and methods for collecting and interpreting textual fragments, some two centuries after their Italian counterparts—the term came to signify an inscription of just about any sort on just about any durable surface (but particularly coins, tombs, and public monuments).73 Again, there is considerable overlap between the kinds of things writers left behind on buildings and in books; and we have only begun to learn from the archaeologists who have wrestled with epigraphic materials and the issues they raise. One particularly promising area for comparison is the archaeological concept of “external symbolic storage”—which is an appropriate description of the function of many used books in early modern England, not least because it conveys the dual status of most books as both utilitarian and symbolic objects (that is, as bearers of symbols and containers of special associations).74 Building on the influential work of Arjun Appadurai on “the social life of things,” John Sutton has combined anthropological and cognitive concerns to outline the ways in which objects serve as “exograms,” or as external repositories for our memories.75 And like “pets and landscapes and cars and friends and ghosts . . . like films and knots and bowls and buildings and unreliable machines,” annotated books “don’t just trigger and unlock memory retrieval, but can also stagger it, halt it, haphazardly twist it, and leave it in disarray” (139). Coming from a still different direction—the fields of information theory and human-computer interaction—John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid have drawn our attention to the ways in which artifacts tend to develop “border resources”: at the boundary between center and periphery, users find new uses for canonical artifacts.76

And this takes us back, finally, to that crucial space from which “marginalia” itself takes its name. The margins bring with them a rich set of historical, sociological, philosophical, and poetic associations—and a repertoire of suggestive terms such as “parergon,” “frame,” “fringe,” and “edge.”77 It is these aspects that connect marginalia to a much wider (and trendier) field of inquiry, and they will no doubt give the term a secure place in our scholarly lexicon for as long as the scholarly imagination finds power in them.

This final section has been little more than a preliminary glossary of Renaissance glosses. Its purpose has not been to take us closer to an approved nomenclature as much as to take us closer to a state of terminological self-consciousness. To prevent these terms from becoming loosely interchangeable or unintentionally anachronistic, we need to recover not only their embedded linguistic histories but also their complex relationships to scholarly disciplines, cultural values, and material practices.