Causal explanations for religious discrimination in the Islamic Republic of Iran

Farhood Badri

Introduction

The Islamic Republic of Iran is one of the most successful states in which religion institutionally captured the whole body politic and discursively became the predominant source of state identity. Since 1979, this post-secular state identity has undergone several changes, oscillating between radicalization and de-radicalization, conservative and moderate interpretations of Islam. These shifts in framing the state identity constitute the fundamental post-secular struggles for discursive hegemony and institutional power in Iran. They became manifest in Iran’s foreign policy as well as domestic reform debates. In contrast to prominent political issues, the chapter asks how these post-secular struggles affect the most vulnerable within Iranian society, non-Muslim religious minorities.

While recognized religious minorities can practise their religion more or less freely, not recognized religious minorities face open discrimination and persecution. Discriminating and persecuting religious minorities in Iran has a long tradition predating the Islamic Revolution in 1978/79 (Sanasarian 2000: 14–16). Nevertheless, since the establishment of the revolutionary and highly complex Islamic state system, this continued practice is much more visible, build on a constructed Islamic collective identity. Constitutionally, the provisions of the Islamic Republic are full of references to Islam and imperatives of being in accord with Islam. Religious freedom is highly regulated, the recognition of religious minorities selective,1 and the description of particular characteristics for non-discrimination is missing the term religion. This trend is reflected in both civil and penal law as well. Moreover, besides the de jure limitations, there are plenty of de facto violations ranging from discrimination and harassment to repression and persecution. However, recognized religious minorities can practice their religion more or less without state interferences, though facing limitations in some areas, such as public employment, anyways. In contrast, not recognized religious minorities openly face discrimination and harassment, are under security surveillance or even, like the Baha’i, forbidden by law. Despite this obvious inequality in the treatment of non-Muslim religious minorities, the varying degree to which their right to religious freedom is denied cannot be explained solely from a rational-choice perspective. In fact, quantitative research (Sarkissian et al. 2011) provides evidence for both rational-choice based and identity-related explanations for religious discrimination.

Apart from some sophisticated works from a rational choice (Gill 2008) or normative political theory perspective (Bielefeldt 2013; Nussbaum 2008), most of the research on religious freedom and religious minorities only provides correlations and no causation (Marshall 2008b; Fox 2008; Grim and Finke 2007). While some authors (Sarkissian et al. 2011) seek to assess the causes for religious discrimination, their findings point to a constructivist gap in research on religious freedom and religious minorities and the need for a more in-depth and context-specific analysis of causal factors for norm violations. Thus, the question why religious minorities are being oppressed and persecuted (differently) by certain states or governments is still awaiting answers and, in particular, the specific causal paths underlying norm violations need to be uncovered.

This chapter intends to contribute to filling this gap with insights from International Relations (IR) norm research and the (sociological) debate on multiple secularities and post-secular (inter)national politics. A qualitative within-case analysis illustrates how the post-secular struggles for discursive hegemony on the Islamic state identity of Iran help to explain the different degrees to which non-Muslim religious minorities are persecuted.

Research on religious freedom and religious minorities

Although most studies on religious freedom and religious minorities only provide correlations and no causation, their results give important insights to possible causal factors impeding compliance with the norm. The most prominent factor accounting for the variances in norm compliance is the separation of state and church or religion respectively. Allegedly, a secular setting, in contrast to religiously identified states like Iran, is commonly seen as the guarantee for religious freedom. But the concept of secularity is extremely varying, from a religious neutrality of the constitutional state up to an anti-liberal or radical state ideology ruling out any form of religiosity in the public sphere (Bielefeldt 2003: Chapter 2–3). “Indeed, extreme religious and extremely secular states together make up the most of the world’s restrictive polities” (Marshall 2008a: 16).

Consequently, it is not important if there is an institutional separation but how the state–religion relation is designed – institutionally or through other bonds – and how, as a result of this design, religion is politically and socially regulated, whereby a high level of regulation results in a high degree of norm violations (Fox 2008; Grim and Finke 2007). This rational-choice-based argument posits that the root cause of religious regulation is competition for influence and political power which drives religious groups to pursue close relationships with political rulers to guarantee their dominant position in society (Sarkissian et al. 2011: 430–431; Gill 2008). If religious institutions or elites have a symbiotic relationship with the government or the state (Fox 2008: 354–355), then these actors support each other in a variety of ways: religious elites provide additional sources of legitimacy to the state; in return, the government supports these religious actors through, for example privileged access to public institutions (like higher education), or even by some form of restriction or repression on other religions (Gill 2008). In extreme cases of this symbiotic relationship even citizenship is connected to religion: “In Saudi Arabia all citizens must be Muslims and in Iran, Kuwait, and the UAE [United Arab Emirates] citizenship is strongly linked to Islam. In Israel, any Jew born anywhere can claim citizenship” (Fox 2008: 355).2

Here, another factor accounting for the cross-national variances in norm compliance is significant: the nexus of religious and national identity. This is where the constructivist gap becomes evident. Although not an exclusive characteristic, this nexus occurs mostly in predominantly Muslim states (Fox 2008: 354). Moreover, an explicitly non-religious, radical atheist form of national identity is possible: the originally Buddhist states China and North Korea perceive themselves as materialistic atheists based on their communist state ideology. For Marshall (2008b: 4), this accounts most for the repression religious minorities face. In general, those states violating religious freedom most intensively share the common feature of a radical state ideology which rests on either religious, secular or nationalistic collective identity (Marshall 2008b: 1). For some rulers of predominantly Muslim states like Iran, Islam serves as a vehicle for national identity as well as a demarcation line against the West and its liberal values. State or government legitimacy is vitally based on this Islamic identity. Consequently, a threat to this identity fundamentally threatens the state’s legitimacy. Religious freedom, the right to change one’s religion and the connected issue of proselytism, in particular, pose an existential threat to the cultural and religious identity of the Islamic political community. They pose a threat because they challenge the established, hegemonic interpretations of norms or visions of the Islamic state with viable alternatives. In fact, the issue is far more complex. In Iran law is bound to religious “affiliation” or “denomination,” and therefore, a change in religion consequently entails a change in status within the legal system. For Muslims, converting to a different religious belief or renouncing religion at all equals apostasy – a sin punishable by death in states like Iran. Note, however, that Muslims can change within denomination (madhhab), moving from Shi‘a Islam to Sunni Islam and vice versa, despite the fact that Sunni Islam is to a certain extent perceived as “less perfect” and that the change in denomination has some legal and political consequences, such as the fact that you are no longer eligible for the presidency of the country, for example. For others than Muslims, it is, of course, possible to convert to Islam or to convert from Judaism to Christianity.

In fact, the findings of the latest quantitative studies confirm identity as an explanation for norm violations (Sarkissian et al. 2011). While the previously mentioned studies only deliver global scores for individual countries, not differentiating between religious minorities within each country, they focus on religious minorities as the unit of analysis. By extending the Religion and State (RAS) data set developed by Fox (2008), the authors present a new module, the Religion and State-Minorities (RASM) data set, which allows for a separate score for each religious minority in each country (Sarkissian et al. 2011: 426). The data set focuses on the aspect of government policy towards religious minorities and defines religious discrimination “as state restrictions on the religious practices or institutions of religious minorities that are not placed on the majority religion” (Sarkissian et al. 2011: 424). Thus, it is possible to identify variance and explore patterns in the treatment of religious minorities (Sarkissian et al. 2011: 431), giving plausible and more reliable insights into causal factors impeding compliance with the norm. Focusing on religious minorities in Muslim-majority countries the authors compared several explanatory factors derived from ideational as well as rational choice-based theories. Among those, the ideational factor of Islamic doctrines and the variation in tolerance according to the religious identity of the minority group, along with the rational choice-based factor of competing for influence and political power – and the thereof assessed close relations between religious authorities and the state – bear the most explanatory potential for norm violations (Sarkissian et al. 2011: 438). On one hand, the authors’ findings confirm that the identity of the religious group matters with regard to the discrimination they face: compared to orthodox Muslim minorities (Sunni or Shi’a), “people of the book” (Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians), other minorities (Hindus, Buddhists) and “apostates” or heretical Muslims (Ahmadis, Baha’is, Druze) are subjected to significantly higher levels of discrimination – in this order (Sarkissian et al. 2011: 440). On the other hand, this finding may also be related to – or even a result of – the close relations between the religious authorities of the majority religion and the state, which is a rational choice-based argument (Sarkissian et al. 2011: 440). Nevertheless, these findings point to the need for a more in-depth and context-specific analysis of causal mechanisms that transmit the detected causal factors for (varying) norm violations.

To conclude, findings from quantitative studies reveal that two interconnected factors stand out especially when explaining the overall poor compliance record of religious freedom: (1) the (institutional) design of state–religion relations and, as a result of this design, how religion is politically and socially regulated and (2) the nexus of religious and national identity and, consequently, the particular identity of religious minorities. These interconnected factors and the constructivist gap sensitize one to the specific context in which – and by whom – religious freedom is interpreted, revealing its divergent cultural validation.

International relations norm research

When it comes to cross-national variance in compliance with religious freedom, IR research on international norms adds valuable insights. Conventional IR norm literature posits that international norms passing through a process of norm diffusion will – under certain conditions – be complied with ending in rule-consistent behaviour of states. Reasons hindering state compliance with international norms are put into two categories: whereas rational compliance approaches point to a lack of either capacity or will of states (Haas 2000), conventional constructivists point to factors of political culture wrapped up in the resonance thesis (Checkel 1999; Cortell and Davis 2000). Indeed, the resonance thesis posits that domestic political structures in terms of state–society relations condition the access to international norms promoted by transnational actors into the national arena. Moreover, the impact of international norms depends on their cultural match in terms of congruence with the domestic political culture, or put differently, “international norms are more likely to be implemented and complied with in the domestic context, if they resonate or fit with existing collective understandings embedded in domestic institutions and political cultures” (Risse and Ropp 1999: 271). In fact, a “misfit” or “mismatch” in domestic resonance potentially explains the variations in compliance with the global norm of religious freedom since it parallels the two interconnected factors for norm violations combining rational-choice-based with ideational explanatory factors.

But what seems plausible at first sight – that is that the variance in domestic political culture helps to explain the cross-national variance in complying with religious freedom – needs to be put into context from a critical constructivist norm research perspective. The problem with the resonance thesis is that, although it rightly acknowledges specific domestic socio-political and socio-cultural contextual settings, it also entails a unidirectional, linear character and normative bias. Thus, it falls under the same line of critique that conventional constructivists face in general.

Until recently, conventional constructivist mainly focused on the emergence, diffusion and power of international norms. In rather linear conceptualizations of norm life cycles (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998) or in spiral models (Risse et al. 1999), norm compliance as an unquestioned internalized rule-consistent behaviour of states was predicted as the final outcome of these inter-/transnational norm diffusion or socialization processes.

Against this conceptualization of rather stable and legitimate norms and linear norm diffusion processes, critical constructivists raised legitimate doubts in several analytical, as well as normative, aspects (Engelkamp et al. 2012; Wiener 2007b). In analytical respect, conventional constructivists tend to neglect, among others, the ideational structure aspect and bottom-up quality of norm emergence (Engelkamp et al. 2012: 104–105; Acharya 2011) and that there is more between the dichotomous binary of full adaption or mere rejection of international norms. A fact that made critical constructivists introduce the concept of norm contestation to show that norms can have different, changing meanings and interpretations. Beyond analytical shortcomings, an implicit normative bias of “good” global or liberal norms in contrast to “bad” local beliefs and practices reveals a severe manifestation of marginalizing and de-legitimizing non-Western value systems and bodies of knowledge, on one hand, and neglecting the historical contingency and the dark sides of allegedly “good” and “widely accepted” liberal norms, on the other (Engelkamp et al. 2012: 104–105, 107–108).

While conventional constructivists conceive norms as rather stable social structures or reference frames influencing state behaviour, critical constructivists conceive norms as significantly more dynamic and flexible (Wiener 2009: 179–180). Critical constructivists such as Wiener begin with the premise that “norms – and their meanings – evolve through interaction in context” (Wiener 2007a: 6). As social constructs, norms are flexible and dependent on the socio-cultural context actors are socialized in. Thus, the very meaning of a norm highly depends on the interactions between the context-specific cultures they are about to be implemented in and the therein socialized individuals. Therefore, norms are contested by default (Wiener 2007a: 6). In this sense, norms are flexible by definition. Nevertheless, they may acquire stability over particular periods, structuring behaviour. This is what Wiener calls the “dual quality” of norms (Wiener 2007b). While norms do have formal validity (the legal framework, such as a constitution or a treaty), the meaning of norms does not necessarily follow from treaty language or organizational practices. Instead the meaning of norms is interpreted according to cultural practices or cultural validation, revealing the so-called meaning-in-use, that is the individual everyday experience or what is customary (Wiener 2007a: 5). Norm contestation thus reflects a specific re- or enacting of normative structures as entailing the meaning-in-use (Wiener 2009: 176).

From an IR perspective the interesting point is that if norms “travel” from one context to another – for example from the nation-state to the transnational arena or vice versa – their meaning becomes contested as organizational and cultural social practices subsequently decouple: “It is through this transfer between contexts, that the meaning of norms becomes contested as differently socialized actors, for example, politicians, civil servants, parliamentarians, or lawyers trained in different legal traditions seek to interpret them” (Wiener 2007a: 12).

Seen from a critical constructivist norm research perspective, the resonance thesis rather serves as a proxy for norm contestation. Cross-national variance in norm compliance, in this understanding, is quasi-happening by default because the meaning of a norm is likely to differ in different socio-cultural domestic contexts. It is exactly this context-specific interrelatedness which conventional constructivists neglect in their unidirectional diffusion models. Here, norm localization comes at play and reveals how processes of norm contestation can range from reinterpretation of global norms to adjusting to or fitting with regional or domestic contexts up to the creation of new regional norms to preserve regional autonomy from dominance and neglect of the outside world (Acharya 2004, 2011).

Research on multiple modernities, multiple secularities and the post-secular

Research on multiple modernities, multiple secularities and post-secular (inter)national politics deal with specific contexts more accurately. This is similar to the critical constructivist’s claim that divergent socio-cultural contexts matter for the meaning of and compliance with norms.

For instance, research on multiple modernities questions the homogenizing and hegemonic assumptions of a specific Western programme of modernity (Eisenstadt 2000: 1–2). In contrast, they unveil the respective context-specific factors like cultural traditions and historical experiences which influenced modern societies or influence processes of modernization (Eisenstadt 2000: 23). These multiple modernities did not evolve conflict-free. Instead, they are the very product of highly contested political struggles over re-interpreting, redefining, and re-appropriating the discourse of modernity in their own context-specific terms (Eisenstadt 2000: 24). In this sense, multiple modernities depict processes of norm contestation or norm localization.

In the same line of argument, IR, political science and, especially, sociological research turned from “secularism to secularisms” (Ghobadzadeh 2015: 17). Analogous to multiple modernities, they speak of multiple secularities pointing to the multiple normative meanings of secularism (and the huge varieties of state– religion relations). In light of the global resurgence of religion, sociologists (of religion) first questioned the secularization thesis. Whether they named it “desecularization” (Berger 1999) or “deprivatization of religion” (Casanova 1994), what they meant was the strikingly visible rise of religious movements, actors and institutions with an explicit (political) ambition to enter the public sphere – the allegedly pure secular domain. These findings prove the secularization theory wrong at least with respect to religious decline and the privatization of religion.3 The varying characteristics and divergent developments of public religions also imply that processes of de- or counter-secularization are context-dependent and thus easily fit within the heuristics of norm contestation.

It took much longer for IR to cope with the global resurgence of religion and the mistakes of secularization theory. This is because of the fact that IR itself is a secular (biased) discipline. In line with the Enlightenment critique of religion, the “fetishization” of the Westphalian paradigm dictated a dominant secular narrative within IR (May et al. 2014: 332–336). From its very beginning, the secular was enshrined within the discipline, despite the Judeo-Christian influences and the context-dependent, specifically Christian historical process of secularization. Seen in this way, the dominant narrative of secularism is a Western, European, Christian “story,” and IR, a secular discipline inherently biased. This is why IR took so long, and had a bit of a hustle, to tackle this blind spot, religion and – as its counterpart – secularism and to finally question and reveal its own normative bias in this respect. Similar to conventional IR norm research, this bias entails a Eurocentric predisposition, assuming that the secular norm will unidirectionally diffuse in all countries resulting in “the same ‘secular’ political order with the same ‘public’-‘private’ distinction” (Hallward 2008: 6; Hurd 2007). In contrast to an overall “compliance” in this sense, divergent secular orders manifest a huge variance in “secular norm compliance” because of divergent socio-cultural contexts, rather revealing processes of norm contestation or norm localization.

Attempts to unveil this bias revealed secularism as a “quasi-religious ideology” (Hallward 2008: 3) and “a faith intolerant of other faiths” (Hurd 2004: 256) and IR as debating “within a single church” (Hurd 2010). Indeed, after a long and insistent period of neglect, more and more IR scholars have recognized the existence of multiple secularities, incorporated the sociological critique of secularization and adopted critical perspectives that pay attention to the context-specific, historical and divergent normative influences and trajectories of secularism. Instead of static and taken-for-granted categories of “religion” and “secular,” which mutually exclude each other, their relationship is conceived as dynamic and flexible, interrelated with historical configurations and context-dependent. Understood as a mode of governance, secularism is the historical contingent result of highly contested political negotiations over the (public) role of religion in politics (Hallward 2008: 3–6): “this ongoing contestation is a dual, interrelated process of repoliticization of the private religious and moral spheres and renormativization of the public economic and political spheres” (Casanova 1994: 5–6). As such, it takes the shape of inner-state contestation processes, which are highly contested struggles between local actors within the same context but with different meanings and interpretations.

To overcome the religious–secular binary, we can capture the resurgence of religion and the multiple meanings of secularism within the concept of post-secular (inter)national politics (Habermas 2008; Mavelli and Petito 2012; May et al. 2014). This move is particularly important in both respects, analytically and normatively: analytically, because the boundaries between the religious and the secular are blurred when, on one hand, religious actors use secular arguments in public discourse, and on the other, secular gatekeepers define what is acceptable or unacceptable (Hallward 2008: 3, 6; Kayaoglu 2014; Badri 2016). From a normative stance, the gatekeeping function is a question of legitimate power. Normatively the connected translation issue appears much more problematic (Habermas 2005): by translating religious arguments into secular terminology, religious actors make themselves vulnerable to secular counter-arguments (Kayaoglu 2014); moreover, these translation efforts disclose an uneven playing field, or an unequal access to contestation (Badri 2016).

But, obviously, there is a need for a re-normativization of the public sphere by explicit religious normative stances. After secularization excluded religion from public discourse modern society lost a vital moral source (Habermas 2005). Quite similarly, the modern secular state rests on preconditions and foundations which it cannot guarantee by itself (Böckenförde 1976): “By excluding religion, secular society becomes impoverished” (May et al. 2014: 337). By contributing to the strengthening of the public sphere of modern societies, public religions become desirable (Casanova 1994: 8). In this sense, religious contestation can enhance the democratic legitimacy of the (global) normative constitutional order, in general, as well as a norm’s legitimacy and strength, in particular (Wiener 2007a: 6).

Consequently, and in the same line of argument, thought-out post-secularism gives room for an explicitly religious contribution to, and even conceptualization of, “liberal” values (Mavelli and Petito 2012: 931).4 For instance, Ghobadzadeh convincingly demonstrates how Islamic religious scholars voice their critique against visions and realities of the Islamic state and speak in favour of a secular democratic order in which religion is separated from the state but not from politics. Remarkably, they ground both their critique and their secular proposal not only on religious sources, arguments deliberately derived from revisionist readings of the Quran and the Hadith, but also from non-jurisprudential principles, such as theological and philosophical reasoning. However, they offer deliberately religious justifications for the institutional separation of religion and state or, more precisely, the emancipation of religion from the state. This is why Gobadzadeh conceptualizes this religious manifestation of secularism with the oxymoronic phrase “religious secularity” (Ghobadzadeh 2015, 2013).

Contesting post-secular discourses on the Islamic state identity in Iran

Ghobadzadeh focuses on the Shia Islamic context of Iran, the focus of this chapter. He understands religious secularity as a politico-religious discourse which contests the very idea of an Islamic state and challenges its foundational legitimacy (Ghobadzadeh 2015: 2). As a genuine Iranian product, religious secularity depicts a revisionist counter-discourse to the predominant or, rather, hegemonic, conservative-traditionalist Shia discourse which institutionalized in the unique revolutionary state system of the Islamic Republic of Iran and delivers the foundational legitimacy of the unification of religion and state. This counter-discourse among reformist religious scholars emerged at the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s as a reaction to the contradictions of the Islamic state: “Disillusioned by the authoritarian excesses of the Islamic state, these scholars, who initially contributed to the institutionalization of the Islamic state in the 1980s, have re-conceptualized the notion of political Islam” (Ghobadzadeh 2015: 3, 2013: 1009). Because of their lived experiences with the Islamic Republic, the very idea of an Islamic state got “disenchanted.”

The religious secularity discourse encompasses two corresponding lines of argumentation: one which stresses the detrimental effects of an Islamic state for genuine (Islamic) religiosity and the other which argues that Islam is compatible with modern political principles like human rights, religious freedom, democracy and secularity. While the former strand posits that religion (or Islam) is incapable of offering all-encompassing governance solutions – a fact that in Iran led to the instrumentalization of Islam, subordinating religion to state politics – the latter argues that only a secular democratic state can provide a conducive environment for genuine religiosity (Ghobadzadeh 2015: 4–6). Again, religious secularity is not promoting the elimination of religion in the public sphere. Instead, it “advocates for public involvement of religion and acknowledges that through its contribution to civil society, religion preserves its role both in the public life and the political process” (Ghobadzadeh 2015: 8). Nevertheless, it does promote an institutional separation of religion and state.

Having said this, religious secularity depicts an “own brand of Iranian secularism” (Ghobadzadeh 2015: 23), a unique indigenous contribution to an Islamic trajectory of secularism: an own Islamic–secular norm which is based on Islamic sources and dynamically emerged out of its own context-specific historical configuration. In this sense, religious secularity depicts an emerging normative meaning-to-be-used structure that contests the hegemonic meaning-in-use structure which (still) is predominant in Iran.

Capturing the religious secularity discourse in reaction to the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and the lived experience of the post-revolutionary state as the desecularized manifestation of political Islam (which in itself was triggered by the authoritarian secularism of the Pahlavi regime), religious secularity itself constitutes a process of re-secularization grounded on a revisionist political Islam. Instead of being consecutive, these discursive processes are mutually constituting but in intense competition and contentious struggles over who becomes hegemonic. Indeed, their discursive and institutional hegemony is the only characteristic which might be consecutive.

In this understanding, one can analyse post-secular negotiations over the public role of religion, and the concrete institutional design of state-religion relations, as (1) contentious societal struggles between “local” actors influenced by competing discourses with divergent underlying meanings of secularism; (2) domestic/inner-state contestation processes, enacting and re-enacting normative meaning-in-use structures; or (3) post-secular struggles over the discursive hegemony of the normative meaning-in-use structure on the Islamic state identity of Iran.

Following Hurd, I conceive secularisms as a “matrix of discourses and practices that […] play a constitutive role in creating agents that respond to the world in particular ways and in contributing to the normative structures in which these agents interact” (Hurd 2010: 135–136). These normative structures or, in critical norm research terms, normative meaning-in-use structures provide guidance for actors insofar as they structure behaviour. Taken separately, each normative structure provides role scripts, prescribes appropriate behaviour, includes and excludes and thus constitutes in- and out-groups. As with critical norm research, I contend that these secularisms as discursive normative structures which structure behaviour are both stable and flexible. If discourses are stable over a prolonged period (because their hegemonic status is not contested), the prescribed behaviour is stable; if discourses are changing (e.g. because of historical contingency), the prescribed behaviour is changing, too; if discourses are contested, the prescribed behaviour is contested as well. In the very moment of contestation, discursive frames struggle and compete for hegemony; the prescribed behaviour becomes ambiguous and opens the floor for alternative appropriations of behaviour in line with the contesting alternative counter-frame. Proponents of the contested hegemonic discursive frame try to defend the status quo by discursively reproducing its hegemonic status: “projects for cultural change are likely to provoke cultural counterprojects from those threatened by them” (Snyder 2002: 9). Altogether, the dual character of discursive normative structures as being stable and dynamically changing helps to explain the behaviour of social actors and delivers causal pathways for the variance in compliance with the norm of religious freedom and religious discrimination, respectively.

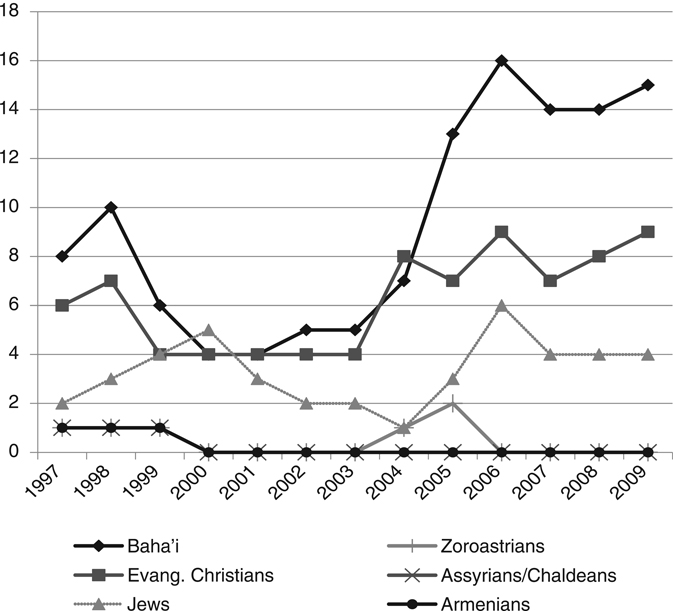

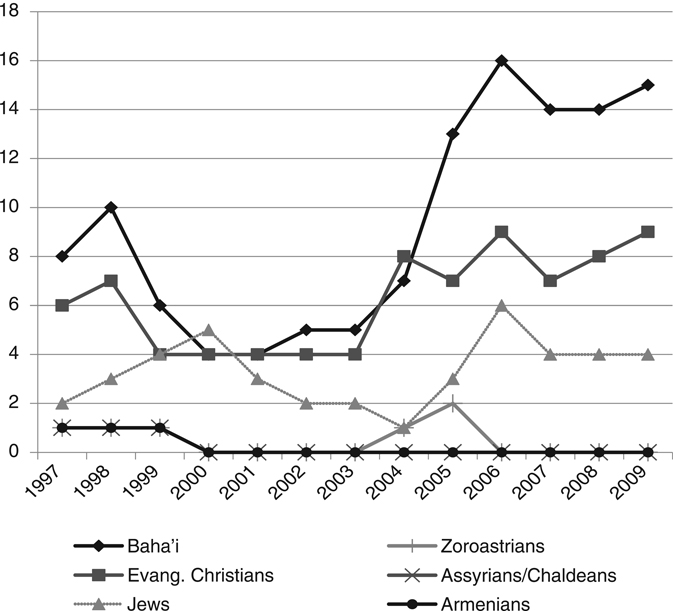

Whereas Ghobadzadeh focuses on religious secularity and state–religion relation within the revisionist Islamic discourse, I focus on a specific subordinate part within that discourse, namely religious freedom, its divergent interpretations and attitudes towards religious minorities. Moreover, while Ghobadzadeh states that this alternative politico-religious discourse influenced the political reform movement in Iran, namely the reformist era during Khatami’s presidency (1997–2005) and the Green movement (2009 onwards), I focus on how this discourse (and its struggle competing with the predominant conservative-traditionalist discourse) influences the politics of reformists (and their counterparts) regarding religious freedom and religious minorities. I do so by examining the degree of norm violation over time in three succeeding presidential terms from 1997 to 2009 – two of president Khatami and one of Ahmadinejad, respectively – focusing on the six non-Muslim religious minorities: Armenians, Assyrians and Chaldeans, Jews, Zoroastrians, Baha’i and Christian converts or Evangelical Christians.

Elite identity framing, religious doctrines and attitudes towards religious minorities

In line with the contested norms argumentation, I focus on the elite’s beliefs, discourses and (symbolic) actions trying to grasp their discursive belonging and how they conceive the meaning of religious freedom and their corresponding attitudes towards the religious other. This meaning depends on their identity framing, whereby this framing is not happening in a vacuum. In fact, it ties in with an already existing collective identity (that of the Islamic Republic of Iran), shaping it into one or another discursive direction, thus enforcing or reducing norm violation. Elite identity framing conceptualizes how state elites construct, reproduce – or, rather, frame and reframe – the Islamic state identity of Iran as within the meaning-in-use structure of the hegemonic conservative-traditionalist discourse or within the revisionist Islamic discourse on religious secularity. For the former, the underlying assumption is that state elites have a vital interest in preserving the predominant frame their legitimacy and power rests on. A (perceived) threat to – or contestation of – their predominant frame equals a threat to their power. Religious freedom poses a specific threat to this frame by challenging the hegemonic meaning-in-use structure with – religiously derived – alternative interpretations of the norm, which allow alternative interpretations of religious doctrines and attitudes towards religious minorities.

Religious doctrines and their respective tolerance demands are standards of appropriate behaviour for a certain group or identity. As Fox exemplifies with certain Islamic doctrines, they can impact on norm violation:

Islam is considered the superior religion and is expected to be given the dominant status in a Muslim state. Members of such religions as Judaism and Christianity are ‘peoples of the book,’ and […] are to be tolerated, but are given second-class status.

(Fox 2008: 355)

Following this logic, believers outside the definition of “peoples of the book,” and especially adherents to religions emerging out of Islam – the so-called apostate religions or heretical Muslim sects – are among those who face the highest levels of discrimination in predominantly Muslim states. But, since religious doctrines are a matter of interpretation, their consent and validity cannot be presupposed, as shown by an internal Islamic reform debate (Kamrava 2006) as well as by their varied application: “In practice, the treatment of non-Muslims differed from one locality and historical period to the next based on the individual ruler” (Sanasarian 2000: 20). Although the extreme interpretation is most common and prominent, Kadivar, a well-known Shia religious scholars and reformist in exile, convincingly demonstrates how universal, that is equal religious freedom, can be derived from Islam’s holy scriptures as well as from the Islamic concept of independent reasoning, ijtihad:

even though most of the interpretations of Islam that are prevalent today augur poorly for freedom of religion and belief, a more correct interpretation, based on the sacred text and valid traditions, finds Islam highly supportive of freedom of thought or religion and easily in accord with the principles of human rights.

(Kadivar 2006: 142)

For operationalizing the tolerance demands out of these doctrines, Appleby’s typology of religious actors is helpful in differentiating in “exclusivists,” “inclusivists” and “pluralists” and their respective tolerance attitudes towards the religious other (Appleby 2000: 13–15). Pluralists practise the highest form of “nonviolent tolerance,” in the sense of “an attitude bespeaking respect for and defense of the rights of others” (Appleby 2000: 14), and even engage in interfaith dialogue. Inclusivists practise a “civic tolerance” where the religious other is tolerated, although only partly recognizing their rights. Exclusivists practice “violent intolerance” towards the religious other. For pragmatic reasons, I differentiate between two poles this tolerance continuum depicts, dividing a rather pluralistic (moderate) and a rather exclusivist (extreme) tolerance attitude.5 For enquiring the identity framing of the elites in power, I focused on state officials and, again for pragmatic reasons, on the respective presidents, and classified each regarding his religious backgrounds (reform-oriented versus traditional-conservative Islam), his rhetoric statements (respectfully appreciating versus disrespectful-contemptuous) and symbolic acts and gestures (reconciliatory versus aggressive) he made during his term of government.

The elite identity framing of Khatami’s presidency can be classified as rather pluralistic/moderate while that of Ahmadinejad as extreme/exclusivist. Regarding the religious background, Khatami definitely belongs to the reform-oriented camp, influenced by the revisionist Islamic discourse on religious secularity which aims at alternative interpretations of Islam, “one that seeks not necessarily to separate Islam from the political process but instead to reform what it sees as an increasingly intolerant and opportunistically motivated interpretation of the religion” (Kamrava 2008: 2). In fact, Khatami propagated a “religious democracy” as a “third way” linking the modern state with the norms and values of Shia Islam (Akbari 2006: 9). In contrast, Ahmadinejad is affiliated to the traditional-conservative Islamic discourse which tries “to theoretically justify the continued dominance of the traditionalist clergy over the entire political system and the cultural life of the country” (Kamrava 2008: 2). His takeover can be described as a radical re-Islamization and silent securitization of the executive, being supported by strongly conservative clerics such as Ayatollah Mesbah Yazdi (Akbari 2006: 12, 18). In fact, Kamrava notes that both camps are grounded in a deep-rooted “intellectual revolution,” “a revolution of ideas, a mostly silent contest over the very meaning and essence of Iranian identity” (Kamrava 2008: 1).

Regarding their rhetoric statements, Khatami can be described as showing a respectful and appreciating rhetoric. As the US State Department notes, “[i]n November 1999, President Khatami publicly stated that no one in Iran should be persecuted because of his or her religious beliefs. He added that he would defend the civil rights of all citizens, regardless of their beliefs or religion” (United States Department of State 2000). In contrast, parallel with Ahmadinejad’s takeover, a huge negative campaign against all non-Muslims started throughout all public media, and anti-Zionistic and anti-Semitic media reports were at their peak.

Concerning symbolic acts and gestures, Khatami’s pragmatism was characterized as “de-sacralizing” political discourse (Akbari 2004: 3) and his foreign policy marked by a “dialogue among civilizations.” Based on his initiative, a minority committee was established, which was ought to exclusively deal with the problems of religious minorities. He also released a presidential order recruiting and re-employing religious minorities in public services. In contrast, Ahmadinejad mainly attracted attention via aggressive acts and gestures. For instance, as a reaction to the Cartoon Crisis, he organized a Holocaust cartoon competition in which the reality and historicity of the Holocaust were put under question. Considering these different discursive belongings and varying elite identity framings, we can expect to find a decrease in norm violation during Khatami’s presidential term and very likely an increase during Ahmadinejad’s presidential term.

Violent integration policies

The assumed causal link between the elite identity framing and the degree of religious freedom violations rests on the mechanism of “violent integration.” The main hypothesis is that the more religious minorities are perceived as challenging or contesting the constructed state identity (by normative difference or actual contestatory behaviour), thus threatening state legitimacy, the more they suffer through violent “integration” policies forcing them to take over the norms and role scripts of the hegemonic frame. The elite’s objective thereby is to contain the challenging threat, preserving the national identity in accordance with the constructed identity frame and thus maintaining legitimacy for the retention of power. The determinants of this mechanism depend on how moderate/pluralistic or extreme/exclusive the collective identity constructed by state elites is and, consequently, how they frame religious freedom and deal with religious diversity and religious minorities, in particular. Following this logic, different elites with varying identity framings differ in their perception of identity threats by religious minorities, thus violating the norm to varying degrees. Consequently, norm violations could de- or increase over time, depending on the identity framing of those in power.

Identity features of religious minorities

In addition to the elite identity framing, the specific identity of religious minorities matters for norm violations insofar as it varies in the degree to which these minorities (perceivably) challenge the collective identity. As mentioned earlier, the identity of religious minorities in Muslim-majority countries can be distinguished in orthodox Muslims, “people of the book,” and apostate or heretical Muslim sects. Since the context of the case study conducted here is Iran and its non-Muslim religious minorities, I focus on Christian denominations, Zoroastrians and Jews as “people of the book” and the Baha’i as an apostate or heretical Muslim sect, respectively.6 According to these two types of religious minorities and following the findings of Sarkissian, Fox and Akbaba, at least two varying degrees of religious discrimination or a perceived challenge or threat to the collective identity, respectively, can be expected.

To allow for a more differentiated, historic- and context-specific approach, additional identity-related factors accounting for this perceived challenge or threat need to be considered as well. Such additional identity-related factors are found in the characteristic features these minorities have. These are the association with the West, the intent to annihilate Islam (Sanasarian 2000: 155), missionary or proselytizing activities, and an ethnic bond.7 Different religious minorities with varying identity features are variably perceived as challenging or threatening the identity framing of those in power, and thus face religious discrimination to different degrees. Accordingly, norm violations could vary among religious minorities, depending on their specific identity features.

Assumptions

According to the conceptualizations made so far, the following assumptions and hypothesis were made: the more moderate/pluralistic the elite identity framing is, the less it seeks to preserve the unitary religious collective identity by force and vice versa. The less a religious minority is challenging the unitary religious collective identity of the state, the less it will face repression and vice versa. Note that this identity threat only needs to be a perceived one (e.g. by normative difference), not actually triggered by real action (contestatory practices) but dependent on the identity framing of the elites in power. Consequently, norm violations and state repression against religious minorities through the mechanism of violent integration policies are more likely the more those in power seek to preserve the unitary religious collective identity of the state and the more religious minorities are perceived to challenge it.

If elites with a moderate/pluralistic framing are in power and a religious minority is not perceived as a threat, repression through violent integration policies is not likely. If elites with a moderate/pluralistic framing are in power and a religious minority perceived as a threat, repression through violent integration policies is not impossible but unlikely. If elites with an extreme/exclusive framing are in power and a religious minority is not perceived as a threat, repression through violent integration policies is not impossible, but unlikely. If elites with an extreme/exclusive framing are in power and a religious minority is perceived as a threat, repression through violent integration policies is very likely.

Non-Muslim religious minorities in Iran

The non-Muslim religious minorities in Iran, beyond their difference in being recognized or not, vary in the degree to which they (perceivably) challenge the collective identity. Armenians, Assyrians and Chaldeans are among the recognized non-Muslim religious minorities. They are all bound ethnically, are not associated with the West and neither undertake any missionary activities nor intend to annihilate Islam. Zoroastrians, recognized as well as “people of the book,” are the most assimilated religious minority because of their long history, dating back to the Persian Empire, and are deeply entangled with Persian culture, thus not being associated with the West. They are moreover bound together by the ethnic bond of being Persian, but this is not as strong (e.g. regarding intermarriages with other denominations) as in the case of other minorities such as the Armenians. Zoroastrians do not undertake missionary activities; nevertheless, their religious sermons are held in Farsi, contrary to the Armenians, Assyrians and Chaldeans. In fact, it is an open question whether their sermons in Farsi, their close cultural ties and their popularity could become a challenge to certain identity frames. Jews are also among the recognized religious minorities. Even though they have an ethnic bond and neither proselytize nor try to annihilate Islam, they are highly associated with the Shah’s regime and, of course, Israel. Evangelical Christians, mostly Muslims who have converted to Christianity, are not a recognized minority. They do not have a specific or strong ethnic bond, undertake missionary activities in Farsi and are associated with the West. The Baha’i are not recognized either. They are highly perceived as an apostate religion or heretic sect evolving out of Islam. Moreover, since their world centre is located in Israel, they are associated politically with the Israeli state as well as the Shah’s regime. Since 1983, they are forbidden by law, framed – or securitized – as a political sect involved in spying activities and conspiracy.

Considering these characteristic features, the Baha’i are expected to be perceived the most as a threat, followed by Evangelical Christians and, then, to a lesser extent Jews. Zoroastrians, Assyrians and Chaldeans as well as Armenians are not expected to challenge the collective Islamic identity, thus facing the least religious discriminations.

Varying degrees of norm violation

The “degree of norm violation” explicitly focuses on the (ill) treatment of religious minorities and served as a starting point to analyse if norm violations do vary over time and between the non-Muslim minorities. It was operationalized on the basis of the Framework for Communications of the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief (UNSR). Nevertheless, because of research pragmatic reasons the all-embracing character of the framework forced me to come to a core of religious freedom aspects relevant to my case, basically covering two dimensions: the dimension of freedom of religion or belief, with six indicators coded 0 if granted and 1 if not granted, and the dimension of discrimination on the basis of religion or belief, with six indicators coded 0 for no discrimination, 1 for ordinary discrimination and 2 for severe discrimination. Following an additive logic, the degree of norm violation for each religious minority could thus be measured on a scale ranging from 0 to 18 on a yearly basis from 1997 to 2009. Note that scoring 0 does not characterize a religious minority to be free or not facing any kind of discrimination at all. It only implies a low degree of norm violation (compared to others). Moreover, since these scores are designed and enquired for the degree of norm violation of religious minorities, they do not reveal anything about the comprehensive dimension of religious freedom in Iran in general or the norm violations the population generally faces. The basic purpose of these indicators is to measure the change in norm violation over time and to allow for comparison of each religious minority. Again, this set of indicators is not depicting the overall dimension of violations to the norm; accordingly, they are to be understood as selective.8

The degree of norm violations was inquired qualitatively on the basis of the annual reports of the UNSR and the religious freedom specific reports of the US Department of State. These reports were analysed using qualitative content analysis by sort and number of norm violations for each non-Muslim religious minority over the period from 1997 to 2009, categorizing them in accordance with the developed indicator sets. In order to broaden the data, the annual reports of human rights non-governmental organizations (NGOs), such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, were consulted as well.

As shown in Figure 7.1, the overall trend of an expected decrease in norm violation during the moderate identity framing of Khatami and an increase by the time Ahmadinejad took over power is confirmed. Furthermore, the variances between the non-Muslim religious minorities confirm the expected trend that the predominant elite frames as well as the specific minority features impact norm violations. Nevertheless, some unexpected ups and downs do occur, which the proposed assumptions cannot fully comprehend. The easiest of these unexpected trends to explain is the question why the norm violations against Armenians, Assyrians and Chaldeans, as well as Zoroastrians, scoring 1 from 1997 are not decreasing until 2000. Arguably, after Khatami’s takeover, it took some time for his identity frame and policies regarding religious minorities to effect a decrease, and this was just delayed. But, in fact, this does not explain the violent integration policies the Baha’i and Evangelical Christians suffered in 1998 and the Jews suffered continually from 1998 to 2000. The same goes for the increases in norm violations starting in 2003, at the end of Khatami’s presidential term. While these two occurrences are still explicable with inner-state dynamics, the heavy ups and downs in Ahmadinejad’s term are not.

Figure 7.1 Norm violation of non-Muslim religious minorities in Iran, 1997–2009

Inter-factional rivalry as post-secular struggles over discursive hegemony

In fact, the two terms in office of Khatami were deeply shaped by the inter-factional rivalry of the Islamic Republic’s political system. While Khatami started his “controlled liberalization” efforts, shifting the collective identity towards a more plural-istic and moderate frame, conservative elites, especially in the judiciary and in the security services apparatus of the executive, perceived this move as a threat to their hold on power: “The appearance of an alternative symbolic universe poses a threat because its very existence demonstrates that one’s own universe is less than inevitable” (Berger and Luckmann 1967: 100). Perceiving a challenge to the status quo by the liberalization and moderate framing efforts Khatami initiated, they had to react or, as Snyder argues, counteract: “projects for cultural change are likely to provoke cultural counterprojects from those threatened by them” (Snyder 2002: 9). Accordingly, they tried to defend or preserve their extreme or exclusivist identity framing from change and, simultaneously, delegitimate Khatami’s reputation at the domestic and international level. For instance, the rapid increase in norm violation against the Baha’i, Evangelical Christians and Jews in 1998 coincides with Khatami’s visit to the UN, where he initiated his Dialogue among Civilizations (Sanasarian 2000: 159). In the same line, in 1999, the UNSR argued that these incidences had to be seen within the special Iranian context “either as reflecting its maintenance of a policy of intolerance and discrimination, particularly against the Baha’is, or as revealing a strategy on the part of conservatives to thwart President Khatami’s progressive advances, or as both at once.”9 These sorts of setbacks caused “from within” commonly occur in countries in transition, with the reform discourse in Muslim countries causing a conservative re-Islamization, as Akbari argues (2006: 12). Indeed, this was intensified by the parliamentary elections in February 2004, when the reformists surrounding Khatami suffered huge losses because, inter alia, the Guardian Council didn’t approve many of its candidates (Akbari 2006: 12). The ground regained by conservatives (and the institutional power they maintained in the judiciary and in the security services apparatus of the executive) could thus explain the increase of norm violations in that year.

Alternative explanations – external pressure

However, another alternative explanation accounts for the several violent integration policies taking place during Ahmadinejad’s presidency: external pressures amplified the mechanism of violent integration policies. External pressure can set in motion a “rally around the flag effect,” leading to nationalistic or, in this case, exclusivist Islamist discourses in order to increase domestic support and legitimacy in the face of international criticism (Risse and Ropp 1999: 243). For instance, Ahmadinejad’s huge negative campaign against all non-Muslims “stressed the importance of Islam in enhancing “national solidarity” and mandated that government-controlled media emphasize Islamic culture in order to “cause subcultures to adapt themselves to public culture” (United States Department of State 2006). Conceived as such, the state “channels” the external pressure it faces by passing it on to the most vulnerable from within, the religious minorities. Thus, external pressure is not the cause of violent integration policies but their possible accelerator, amplifying their impact.

Note that external pressure doesn’t necessarily need to be norm specific. Indeed, we can differentiate between (1) norm-specific external pressure, in this case mostly by the UNSR (and, to a lesser extent, the emerging religious freedom specific advocacy network); (2) a more general transnational pressure, for instance those of Amnesty International’s campaigning against Iran’s human rights record; and (3) pressure from the international community, specifically the immense pressure the international community used to settle the nuclear crisis with Iran. Although this nexus is even more complex since we leave the domestic sphere entering the inter- or transnational level, it is at least plausible: by paralleling the timeline of norm violations with the three forms of external pressures Iran faced during this period, the peaks of these pressures coincide with the respective peaks caused by (amplified) violent integration policies. This is a plausible nexus which needs to be focused on in further research.

Conclusion

Post-secular struggles over the Islamic identity of Iran seem to help with exploring causal explanations for varying religious discrimination. Contentious discourses over the meaning of religious freedom, alternative interpretations of religious doctrines and the attitudes towards religious minorities fit well for unveiling causal mechanisms that transmit casual factors to varying degrees of norm violation. Indeed, both rational-choice and identity-related factors have their say in explaining religious discrimination. Whereas research on religious freedom and religious minorities discusses whether ideational factors like religious doctrines and the identity of religious minorities ultimately are predictable by rational-choice based arguments, I contend that this approach suffers from a constructivist gap. It is not about which of them actually matters; it is much more about what constructivism, in general, tells us about bridging the rationalistic-constructivist divide: to know what I want, I need to know who I am. While rational-choice arguments alone can explain why religious minorities, in general, suffer discrimination, the varying degrees of religious discrimination cannot be fully comprehended without considering the impact of identity on actor’s preferences.

Combining research on religious freedom and religious minorities with critical norm research, multiple modernities/secularities and post-secular (inter)national politics, enables us to come closer to a comprehensive, though not exhausting, explanation and understanding of religious freedom violations. Capturing these norm violations as post-secular struggles within the heuristics of norm contestation by focusing on inner-state contestation processes within the very same socio-cultural context, but by local actors influenced by competing discourses, adds considerable value to critical norm research.

However, the depicted post-secular struggles are context-dependent and only speak for the within-case analysis conducted here. Nevertheless, they convincingly demonstrate that the normative power of contestatory discourses to actually change the status quo is limited. Institutional power matters as well, especially in the highly complex state system of Iran, in which conservative-traditionalist interpretations of Islam institutionally captured the whole body politic and discursively became the predominant source of state identity. If contesting discourses (meaning-to-be-used structures) fail to institutionalize adequately, their socio-cultural validation will not be put into practice, leaving enough room for opponents of the contested discourse to counteract, defending and reframing their hegemonic meaning-in-use structure.

Notes

References

Acharya, Amitav (2004) “How Ideas Spread: Whose Norms Matter? Norm Localization and Institutional Change in Asian Regionalism,” International Organization, 58(2), 239–275.

Acharya, Amitav (2011) “Norm Subsidiarity and Regional Orders: Sovereignty, Regionalism, and Rule-Making in the Third World,” International Studies Quarterly, 55(1), 95–123.

Akbari, Semiramis (2004) “Iran zwischen amerikanischem und innenpolitischem Druck: Rückfall ins Mittelalter oder pragmatischer Aufbruch?,” HSFK-Report 1/2004, Frankfurt a.M.

Akbari, Semiramis (2006) “Grenzen politischer Reform- und Handlungsspielräume in Iran: Die Bedeutung innenpolitischer Dynamiken für die Außenpolitik,” HSFK-Report 9/2006, Frankfurt a.M.

Appleby, R. S. (2000) The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence, and Reconciliation, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Badri, Farhood (2016) “Religious Freedom: IR and Islamic Perspectives on a Globally Contested Norm,” paper presented at the 3rd European Workshops in International Studies, Tübingen, April 6–8, 2016.

Berger, Peter L. (ed.) (1999) The Desecularization of the World: Resurgent Religion and World Politics, Washington, DC: Ethics and Public Policy Center & W.B. Eerdmans.

Berger, Peter L. and Thomas Luckmann (1967) The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge, New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Bielefeldt, Heiner (2003) Muslime im säkularen Rechtsstaat: Integrationschancen durch Religionsfreiheit, Bielefeld: Transcript.

Bielefeldt, Heiner (2013) “Misperceptions of Freedom of Religion or Belief,” Human Rights Quarterly, 35(1), 33–68.

Böckenförde, Ernst-Wolfgang (1976) “Die Entstehung des Staates als Vorgang der Säkularisation,” in Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde (ed.), Staat, Gesellschaft, Freiheit: Studien zur Staatstheorie und zum Verfassungsrecht, Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp, pp. 42–64.

Casanova, José (1994) Public Religions in the Modern World, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Checkel, Jeffrey T. (1999) “Norms, Institutions, and National Identity in Contemporary Europe,” International Studies Quarterly, 43(1), 84–114.

Cortell, Andrew P. and James W. Davis (2000) “Understanding the Domestic Impact of International Norms: A Research Agenda,” International Studies Review, 2(1), 65–87.

Eisenstadt, Shmuel N. (2000) “Multiple Modernities,” Daedalus, 129(1), 1–29.

Engelkamp, Stephan, Katharina Glaab and Judith Renner (2012) “In der Sprechstunde: Wie (kritische) Normenforschung ihre Stimme wieder finden kann,” Zeitschrift für Internationale Beziehungen, 19(2), 101–128.

Finnemore, Martha and Kathryn Sikkink (1998) “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change,” International Organization, 52(4), 887–917.

Fox, Jonathan (2008) A World Survey of Religion and the State, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Ghobadzadeh, Naser (2013) “Religious Secularity: A Vision for Revisionist Political Islam,” Philosophy & Social Criticism, 39(10), 1005–1027.

Ghobadzadeh, Naser (2015) Religious Secularity: A Theological Challenge to the Islamic State, New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gill, Anthony (2008) The Political Origins of Religious Liberty, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Grim, Brian J. and Roger Finke (2007) “Religious Persecution in Cross-National Context: Clashing Civilizations or Regulated Economies?,” American Sociological Review, 72(4), 633–658.

Haas, Peter M. (2000) “Choosing to Comply: Theorizing from International Relations and Comparative Politics,” in Dinah Shelton (ed.), Commitment and Compliance: The Role of Non-Binding Norms in the International Legal System, Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press, pp. 43–64.

Habermas, Jürgen (2005) “Religion in der Öffentlichkeit. Kognitive Voraussetzungen für den ‘öffentlichen Vernunftgebrauch’ religiöser und säkularer Bürger,” in Jürgen Habermas (ed.), Zwischen Naturalismus und Religion, Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp, pp. 119–154.

Habermas, Jürgen (2008) “Notes on Post-Secular Society,” New Perspectives Quarterly, 25(4), 17–29.

Hallward, Maia C. (2008) “Situating the ‘Secular’: Negotiating the Boundary between Religion and Politics,” International Political Sociology, 2(1), 1–16.

Hurd, Elizabeth S. (2004) “The Political Authority of Secularism in International Relations,” European Journal of International Relations, 10(2), 235–262.

Hurd, Elizabeth S. (2007) “Political Islam and Foreign Policy in Europe and the United States,” Foreign Policy Analysis, 3(4), 345–367.

Hurd, Elizabeth S. (2010) “Debates within a Single Church: Secularism and IR Theory,” Zeitschrift für Internationale Beziehungen, 17(1), 135–148.

Kadivar, Mohsen (2006) “Freedom of Religion and Belief in Islam,” in Mehran Kamrava (ed.), The New Voices of Islam: Reforming Politics and Modernity: A Reader, London: I.B. Tauris, pp. 119–142.

Kamrava, Mehran (ed.) (2006) The New Voices of Islam: Reforming Politics and Modernity: A Reader, London: I.B. Tauris.

Kamrava, Mehran (2008) Iran‘s Intellectual Revolution, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Kayaoglu, Turan (2014) “Giving an Inch Only to Lose a Mile: Muslim States, Liberalism, and Human Rights in the United Nations,” Human Rights Quarterly, 36(1), 61–89.

Marshall, Paul A. (2008a) “Secular and Religious, Church and State,” in Paul A. Marshall (ed.), Religious Freedom in the World, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 12–16.

Marshall, Paul A. (2008b) “The Range of Religious Freedom,” in Paul A. Marshall (ed.), Religious Freedom in the World, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 1–11.

Mavelli, Luca and Fabio Petito (2012) “The Postsecular in International Relations: An Overview,” Review of International Studies, 38(5), 931–942.

May, Samantha, Erin K. Wilson, Claudia Baumgart-Ochse and Faiz Sheikh (2014) “The Religious as Political and the Political as Religious: Globalisation, Post-Secularism and the Shifting Boundaries of the Sacred,” Politics, Religion & Ideology, 15(3), 331–346.

Nussbaum, Martha C. (2008) Liberty of Conscience: In Defense of America’s Tradition of Religious Equality, New York, NY: Basic Books.

Risse, Thomas and Stephen C. Ropp (1999) “International Human Rights Norms and Domestic Change: Conclusions,” in Thomas Risse, Stephen C. Ropp and Kathryn Sik-kink (eds.), The Power of Human Rights: International Norms and Domestic Change, Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press, pp. 234–278.

Risse, Thomas, Stephen C. Ropp and Kathryn Sikkink (eds.) (1999) The Power of Human Rights: International Norms and Domestic Change, Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Sanasarian, Eliz (2000) Religious Minorities in Iran, Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Sarkissian, Ani, Jonathan Fox and Yasemin Akbaba (2011) “Culture vs. Rational Choice: Assessing the Causes of Religious Discrimination in Muslim States,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 17(4), 423–446.

Snyder, Jack (2002) “Anarchy and Culture: Insights from the Anthropology of War,” International Organization, 56(1), 7–45.

United States Department of State (2000) “Annual Report on International Religious Freedom 2000,” Washington, DC.

United States Department of State (2006) “Annual Report on International Religious Freedom 2006,” Washington, DC.

Wiener, Antje (2007a) “Contested Meanings of Norms: A Research Framework,” Comparative European Politics, 5(1), 1–17.

Wiener, Antje (2007b) “The Dual Quality of Norms and Governance beyond the State: Sociological and Normative Approaches to ‘Interaction’,” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 10(1), 47–69.

Wiener, Antje (2009) “Enacting Meaning-in-Use: Qualitative Research on Norms and International Relations,” Review of International Studies, 35(1), 175–193.