Can the Italians’ aversion to tomatoes be explained by the negative attitude toward fruits and vegetables that prevailed in Renaissance Italy? It was said of Prince Francesco de’ Medici, Cosimo’s son, that he ate all the wrong foods for a man of his elevated status:

gross and trivial foods … hard to digest, like garlic with black pepper, onions, leeks, shallots, wild garlic, strong raw onions, wild radishes, radishes, horseradish, rampions, artichokes, cardoons, artichoke shoots, celery, arugula, nasturtiums, chestnuts … truffles and, in vast quantities, every kind of cheese.

Maybe Francesco’s physicians were right. After all, he did die fairly young, not of vegetarianism, though, or even of malaria (as was previously thought), but of arsenic poisoning.

Renaissance physicians lay at the heart of this negative attitude. The dietary advice they gave could not have been clearer. But was anyone paying attention?

Books on health maintenance and hygiene were popular from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. One of the most successful writers was Tommaso Rangone, a celebrated physician from Ravenna. His manual on “how to live to the age of 120” was first printed in 1550, and to judge by Rangone’s medical advice, no one in his right mind would have dared consume vegetables for the various life-threatening infirmities they caused. Foods like vegetables and fruits, perceived as qualitatively watery and viscous, were always vilified, as they got trapped in the body’s membranes and putrefied. The moisture had negative effects on the brain, compromising wit and intelligence and, in extreme cases, leading to melancholy. Many vegetables were regarded as suitable only for rustics and laborers, who alone had the bodily heat necessary to counter their cold and moist qualities and the strong stomachs to digest them.

Medical fears of vegetables were occasionally echoed in the culinary literature. The Florentine steward Domenico Romoli (“Il Panonto”) concludes his culinary manual, La singolar dottrina di m. D. Romoli detto il Panonto (1560), with a “treatise on the maintenance of health.” It does not contain a single reference to vegetables. Elsewhere in the book, Romoli advises that “for the maintenance of his health, neither fruits nor plants must a man use as food, because they dampen the humors and do not give nourishment.” At best, their cold and humid qualities might be rendered less harmful by being cooked with “hot” ingredients and served on only the hottest of days.

Contemporaries seem to have taken this medical advice with a grain of salt, metaphorically as well as literally. While the success of dietary manuals points to a widespread interest among the elites, satires of the literature suggest the difficulties in following their advice.

Not least of these difficulties were the physicians’ contradictory opinions, plus the desire of Renaissance princes and their courtiers to eat what they liked. Because they were rich and leisured, they were the recipients of much of this advice, as it was believed that they alone had the luxury of being able to make dietary choices. But according to the French physician Laurent Joubert, “[Courtiers] never cease interrogating physicians when at the table: Is this good, is this bad or unhealthy? What does this do? Most who ask have no desire to observe what the physician says, but they take pleasure in doing it, for entertainment.” Consequently, evidence of princes and courtiers eating all the wrong foods, despite the medical advice, abound.

In fact, edible plants were widely consumed, and not just by Francesco de’ Medici. In Le vinti giornate dell’agricoltura e dei piaceri della villa, an agricultural treatise printed in 1569, just twenty years after Rangone’s manual, Agostino Gallo lists what were then common garden vegetables grown for their usefulness and health-giving properties, which Gallo also details. These were cabbages, leeks, garlic, onions, fennel, carrots, squashes, turnips, radishes, peas, shallots, erba sana (allgood, a kind of wild spinach), artichokes, and asparagus. From the point of view of plant husbandry, root vegetables were just as favored as leaf vegetables. Rangone must have been rolling in his grave!

Gallo, a merchant and landowner in Brescia, offers a more accurate snapshot of actual consumption habits than does the physicians’ advice. In addition to these common garden vegetables, under “recreational” gardens Gallo lists plants grown for their flavor and for salads (lettuce, radicchio, tarragon, arugula, sorrel, borage, and parsley), soups, and other uses (mint, pennyroyal, Swiss chard, and spinach). Finally, plants were grown in pots to decorate gardens (basil, marjoram, and other “kinds of lovely and sweet-smelling herbs”). None of the plants that Gallo discusses comes from the New World.

Costanzo Felici, a physician and observer of nature with no ax to grind, confirms the impression of a vegetable vogue. Felici notes that the word insalata comes from the basic seasoning for edible plants—salt—whether raw or cooked, along with oil and vinegar. The salt serves to dry “the insipid humidity of the herb” and “to give pleasure as well as to prevent it from becoming corrupted and putrefied in the ventricle.” He criticizes, however, the way that “salads” are eaten indiscriminately at different times of the day or at different points in the meal, often with no other purpose than to stimulate the appetite so that diners can eat more. Felici is not just referring to elite habits. He also reminds his readers that “toward the end of winter and the beginning of spring, it is said as a proverb among women that any green plant will do for a salad.”

The consumption of vegetables was clearly on the rise. The physician Salvatore Massonio reflects this growing passion for edible plants, informing his reader that he has written his erudite Archidipno (Beginning of the Meal, 1628) in response to his love of eating salads: “overly pleasing to me and all too frequent.” This is a guilty pleasure, as Massonio is bothered that salad, “although so common that it is either eaten or at least known by everyone,” is hardly mentioned by ancient writers. Some contemporary physicians continued to have doubts, too. In his advice for magistrates and scholars, Guglielmo Gratarolo commends eating lettuce and endive in salads as “wholesome,” but only in hot weather. He admits that colewort and cabbages might be healthy, at least during “cold and moist seasons,” although he is worried that the Germans eat them primarily to counteract the effects of too much wine.

In fact, edible plants have a long history as a mainstay of Italian regional diets. In 1596, the English courtier and Italophile Robert Dallington wrote that for poorer Tuscans, “their chiefest food is herbage all the yeare through.” “Herbage,” he continues,

is the most generall food of the Tuscan, at whose table a sallet is as ordinary as salt at ours; for being eaten of all sorts of persons, and at all times of the yeare: of the rich because they love to spare; of the poore because they cannot choose; of many Religious because of their vow, of most others because of their want. It remaineth to believe that which themselves confesse; namely, that for every horseload of flesh eaten, there is ten cart-loades of hearbes and rootes; which also their open markets and private tables doe witnesse.

Dallington’s reference to markets is important. The presence of a piazza delle erbe in many Italian towns is testimony to the importance of vegetables to both diet and commerce. Savona’s “piaza publica de herbe” was where “the most beautiful vegetables” were sold, in the words of a local notary and chronicler, Ottobuono Giordano. In the early sixteenth century, Giordano claimed, with more than a touch of local pride, that the quantity of vegetables sold there was such that “if I went in the morning I would say that they wouldn’t finish selling them within a month, but by evening nothing is left. And there are all sorts of vegetables, in both winter and summer.” Moreover, this was in Liguria, a part of Italy where cultivating anything meant having to build and maintain terraces in the steep mountainsides, watered by elaborate irrigation systems and carefully fertilized. Nonetheless, the demand for salad was such that Savona’s bishop exempted greengrocers and market gardeners from the prohibition against working on Sundays and feast days in order to supply the market with it. Giordano was not exaggerating about the uninterrupted, year-round cultivation of vegetables. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the same thing impressed the Napoleonic prefect Gilbert Chabrol de Volvic.

Like many Italian towns, Savona had its own trade guild of greengrocers and market gardeners (ortolani), and Turin’s ortolani formed a religious association or confraternity. Some of its members even signed their own names, which was an indication of their rising social status. Gardeners like them would have farmed both inside the town walls and outside in the surrounding countryside. Turin had a network of such gardens, which were sometimes rented out to women. The produce from the market gardens in and around Italian towns formed the bulk of what was sold in their market squares. Thus Goethe noted in May 1787 that “the immediate area around Naples is simply one huge kitchen garden, and it is a delight to see … what incredible quantities of vegetables are brought into the city every market day.” These gardens were meeting the insatiable demands of what was then one of Europe’s largest cities, since Naples was third in size after London and Paris.

By the late sixteenth century, the elites were eating vegetables too, as Dallington suggests. The food of the poor was becoming the food of the rich, even though for the rich, vegetables were only one of a series of dishes served, generally cold. In the early sixteenth century, vegetables were still something of a novelty at court, just beginning to find their way into the myriad dishes, small and large, used to impress visitors. Indeed, the increasing presence of vegetables on elite tables has a whiff of reverse snobbery about it, as Renaissance banquets were scenes of conspicuous consumption and political propaganda as well as occasions for conviviality.

As early as the late fifteenth century, Martino of Como, cook to the Sforza dukes of Milan, included recipes for vegetables in his collection of relatively simple and straightforward dishes. Bartolomeo Sacchi, a cook and humanist par excellence—his status evident in his Latin name, “Platina”—noted the health benefits, or at least how to correct the harmful effects, of a variety of vegetables, such as turnips, spinach, and cabbages.

Perhaps stirred by this advice, in 1519 Isabella d’Este, marquise of Mantua, sent some cabbage seeds to her brother, the duke of Ferrara, “to eat in a salad.” These were followed by some actual cabbages “so he can give them a try” (figure 9). Since the duke evidently was unaccustomed to such humble fare, Isabella explained to him that the stems had to be removed first and that the cabbages should be boiled briefly until tender and then seasoned with oil and vinegar, “like a salad.” “Your Excellency will then see if this oddity is pleasing to him,” she concluded.

Figure 9 An oddity fit for a duke: the cabbage. (From Pietro Andrea Mattioli, I discorsi … della medicina materiale [Venice: Felice Valgrisi, 1595])

Edible plants became fashionable at court, especially if they could be presented in elaborate ways (whatever the physicians might say). Giovanni Battista Vigilio’s recipe dating from the late sixteenth century, “to make a tasty and lovely salad,” consists of fifteen edible plants, seven flowers, nine fruits, and twelve seasonings. Indeed, his idea of a “salad”—as well as the name that he gave to his gossipy chronicle of life at the Gonzaga court—was the “mixing of diverse and various things.”

The Italians’ consumption of edible plants had regional differences in both caricature and fact. The Lombards were ridiculed as mangiarape (turnip eaters), the Cremonese as mangiafagioli (bean eaters; but the poor Florentines as cacafagioli [bean shitters]), and the Neapolitans as mangiafoglie (leaf eaters).

Regarding the “leaf eaters,” Emilio Sereni explains that in the Neapolitan dialect of that time, foglie referred primarily to broccoli, although not quite the modern variety. The label of “broccoli eaters” was well deserved, as the vegetable was cultivated throughout the year to provide Naples with a steady supply. All parts were eaten—leaves, stems, and flowers—and they were apparently enjoyed by all members of society, from gourmands to paupers, according to a 1646 poem written in praise of broccoli. Not just the Neapolitans loved broccoli. A recipe for “Roman broccoli” (cavoli alla romanesca) appears in Martino of Como’s recipe collection. This “incomprehensible predilection” for broccoli was shared by the inhabitants of Rome well into the nineteenth century, according to a French physician stationed there. Félix Jacquot referred to broccoli as the “conqueror of pasta” (le vainqueur du macaroni) and noted that the broccoli was cooked all day long in vast cauldrons and bought, piping hot, by neighborhood housewives. Both Martino and Jacquot may have been referring, however, to what are today known in Italy as broccoli romaneschi (Romanesco broccoli), a light-green cauliflower, combining the form of cauliflower with the sweetness of broccoli.

Neapolitans ate other vegetables too, of course. In 1692/1623, at the Ospedale dei Pellegrini in Naples, a charitable home for pilgrims and the homeless, the basic meal of cabbage, squash, or turnip soup plus salad and fruit was distributed everyday to everyone: staff, pellegrini, and convalescents. Large urban religious institutions like the Ospedale dei Pellegrini were great consumers of agricultural produce, as were aristocratic households, and they also were often great producers of it. We know this because they generally kept detailed records, some of which survive for historians to study.

Religious institutions made a virtue of a diet rich in vegetables, so we find nuns eating a large quantity and variety of vegetables in soups, seasoned with lardo, which is, strictly speaking, hard bacon fat rather than lard. Olive oil was used more for lighting lamps than for cooking, for which purpose it was reserved for “lean” or meatless days. Later, during the eighteenth century, some vegetables were served raw as a sopratavola to nibble on throughout the meal. Fennel, celery, and radishes were eaten in this way. In southern Italy, the Poor Clares of Santa Chiara (Francavilla Fontana, Puglia) made 461 separate vegetable purchases during the year 1748/1749, as did the Capuchin nuns of Santa Maria degli Angeli (Brindisi, Puglia) during 1755/1756. Indeed, in the early 1790s, the nuns of Santa Maria degli Angeli ate a vegetable soup almost daily—made from cauliflower, chicory, cardoons, escarole, or cabbage—as well as vegetables like squash, eggplant, broccoli rabe, artichokes, and lampaggioli (a small bitter onion).

The Jesuit priests of Turin were concerned about both the careful administration of their estates and a healthy diet to ensure the accurate record keeping of both production and consumption, and their records detail their increasing cultivation of vegetables and fruit during the eighteenth century. Likewise, aristocratic households combined consumption with production. In areas like Piedmont, Liguria, Lombardy, the Veneto, and Sicily, the second half of the seventeenth and the entire eighteenth century saw the flowering of the aristocratic villa, and the post of head gardener became an important administrative position. Thus the gardener of Vische castle, outside Turin, was reminded that

like a good and diligent father of a family and careful gardener, [he will] attend to the culture of the gardens … that is, for fruit, flower, citrus, and vegetable [gardens], [he will] tidy and cultivate as a consequence every fruit tree, whether espalier, bush, or standard, in the said gardens and nearby vineyards … [and] water [them] … to obtain the greatest produce possible from them … according to the best rules of the art.

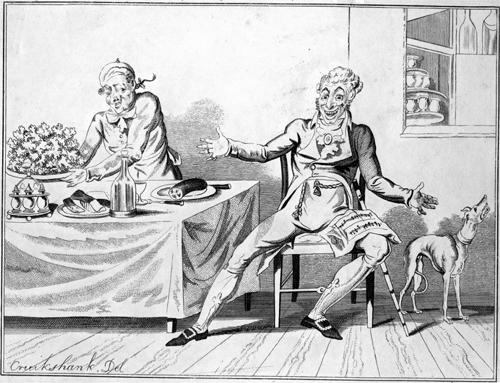

To northern Europeans, the Italians—like the French—were infamous for their love of vegetables. Despite an increasing and increasingly varied consumption of vegetables in England, at least by the upper classes, many English remained wary of “sellets” and other vegetables. This suspicion could have very real consequences. In 1669, an Englishwoman took her French husband to court, alleging cruel treatment, which included his leaving her meatless and very hungry, since he was—to quote from the wife’s deposition—“a Frenchman and useth the diet of herbs and other slight eating.” The salad stereotype persisted for 150 years in the land where eating beef was considered a patriotic duty. Isaac Cruikshank’s print The Celebrated Mock Italian Song (1808) ridicules both the Italian dietary custom and its fashionability in English coffeehouses (figure 10):

With penny-o he will buy any,

If it have Dandilioni,

Saladini, beetrootini,

Endivini, celerini,

Napkinnini swingidini, …

Similarly, Polish satirical poetry of the seventeenth century speaks of the sons of Polish patricians who go to study in Italy, especially at the university in Padua. But they are soon forced to return, complaining of being given only salad to eat and never getting a decent portion of meat. Given this, it is ironic that contact with Italy was crucial to the introduction of vegetables to the Polish diet. Indeed, the Polish language abounds with Italian terms for vegetables. The words used in Poland for tomato, cauliflower, onion, asparagus, zucchini, and chicory are Italian, as is the general term for greens and soup vegetables, włoszczyzna (literally, “Italian things”).

Figure 10 The continuing salad stereotype, in Isaac Cruikshank’s The Celebrated Mock Italian Song (1808), printed by Laurie & Whittle, London. (© Trustees of the British Museum)

According to Polish tradition, vegetables were introduced by Princess Bona Sforza d’Aragona and her retinue when she came from Bari to marry King Sigismund I in 1517. During her four decades in Poland, her cooks supposedly prepared the Italian specialties of the time. But this may be something of a myth, similar to crediting Catherine de’ Medici with single-handedly creating modern French cuisine through her Italian influence, following her marriage to Henri II in 1533. In fact, however, Polish commercial and culinary contacts with Italy date back to the fourteenth century.

In any case, national variations in diet were believed to exist for a reason; that is, they were the result of differing climates and constitutions, which one disregarded at one’s peril. The “heat” of digestion of northern and southern Europeans differed because their climates differed, and the inhabitants were expected to eat accordingly. Novelty in diet posed hidden dangers. William Harrison, writing in the late sixteenth century, deplored the recent fashion among English merchants and nobles of eating dangerous foods like “verangenes” (eggplants), “as if nature had ordained all for the belly.” Such action went against the divine order of things. Only when new plants had become fully acclimatized would they become transmuted into native—and therefore safe—commodities. John Gerard said much the same in regard to eggplants, which never ripened in the English climate: “I rather wish English men to content themselves with the meat and sauce of our owne country, than with fruit and sauce eaten with such peril; for doubtlesse these [eggplants] have a mischievous qualitie, the use whereof is utterly to bee foresaken.” Gerard concludes, “It is therefore better to esteem this plant and have it in the garden for your pleasure and the rarenesse thereof, than for any virtue or good qualities yet knowne.”

An Italian living in England, Giacomo Castelvetro, had tried to buck this trend. In 1614, he found himself in England on the run from the Inquisition in Italy for his Protestant beliefs. A keen promoter of Italian culture, Castelvetro dedicated his “Brief account of all the roots, plants and fruits that raw or cooked are eaten in Italy” (1614) to the Italophile Lucy Russell, countess of Bedford. Castelvetro’s quixotic mission—aside from a search for patronage—was to encourage the English to eat more vegetables and fruit and less meat and fewer overly rich dishes and sweet things. He was not very successful. Although several manuscript copies of the short work survive, it was not translated and published until our own time. Castelvetro did not obtain any patronage, either.

Nevertheless, his essay is a breath of fresh air when compared with contemporary medical-dietary treatises, conservative in their Galenical ideas and heavy on the theorizing. Castelvetro wears his knowledge lightly, but more than that, he is not really concerned with the notion of a close fit between national constitutions and national diets. Rather, what is good for the Italians and the French must also be good for the English. The benefits of vegetables—“they are refreshing, they do not thicken the blood, and above all, they revive the flagging appetite”—applied to all people.

Castelvetro was familiar with the tomato, as we saw in chapter 1, but his interest appears to have been limited to exchanging seeds. At this stage, the tomato was still too new to be included in a treatise on culinary practices, but the eggplant, botanically associated with the tomato, merits an enthusiastic entry in Castelvetro’s essay. Evidence of eggplants in Italy is contradictory. Many people were still suspicious of them. Although prevailing medical notions were partly responsible, their association with Italy’s Jews was no doubt a factor, too. When they were expelled from Spain, Jews and Jewish converts from Andalusia may have brought their taste for eggplants with them. In addition, many Italian Jews had contacts with the Middle East, where they sometimes sought refuge and where the eggplant originated. Yet it is strange that until the nineteenth century, eggplants are virtually absent from contemporary descriptions, in both Hebrew and Italian, of Italian Jewish dietary habits. Their consumption appears to have been limited to poor Jews. In any case, though, in Florence as late as the 1850s, eggplants were apparently still difficult to find and were disdained by many people as “food of the Jews.” By contrast, in southern Italy from at least the end of the eighteenth century, they were being widely consumed, as we shall see later.

In the seventeenth century, the consumption of vegetables rose throughout Europe, and this continued into the following century. New varieties of plants kept up the public’s interest. John Evelyn, an English virtuoso and fellow of the Royal Society, wrote in praise of the “wholesomeness of the herby-diet,” and Louis Lémery, a French chemical physician, extolled the value of the plant-based diet of primitive society, “when men lived longer and were subject to fewer diseases than we.”

Neither writer appears to have been a vegetarian, and, indeed, the word itself was not coined until the mid-nineteenth century. Few writers were willing to recommend a vegetables-only diet, except for certain categories of sick people. Nonetheless, when he was the grand duke of Tuscany, Cosimo III apparently became a complete vegetarian under the advice of his physician, Francesco Redi. Otherwise, physicians tended to scorn the idea that “one can substitute without risk a meager (vegetable) diet for one of flesh,” to quote the Frenchman Nicolas Landry.

The Florentine physician Antonio Cocchi disagreed (figure 11). Cocchi’s Del vitto pitagorico was published in 1743 and, two years later, translated into English as The Pythagorean Diet, of Vegetables Only, Conducive to the Preservation of Health, and the Cure of Disease. Cocchi claimed that Tuscans were among the healthiest people in the world. The reason was their poverty, which forced them to rely on vegetables and fruit and eat very little meat (reiterating Dallington’s comments of 150 years earlier). Cocchi put his own gloss on the latest physiological understandings of the digestive process to explain how a vegetarian diet would benefit people. Optimal nutrition depended on what Cocchi called “subtlety”: the lightness, clarity, and mobility of the body’s fluids. A meat-based diet was too dry and difficult to digest, clogging the body’s passages; by contrast, fruits and plants provided a more readily abundant and usable form of fluid.

Figure 11 The physician and vegetarian advocate Antonio Cocchi. (From Cocchi, Discorsi e lettere, vol. 1 [Milan, 1824])

Cocchi turned to the ancient ascetic Pythagoras for his inspiration, and not the “barbaric school” of ancient physicians, who had regarded fruits and vegetables as too watery and phlegmatic (their ideas had been revived in the Renaissance). Cocchi’s advice is to avoid all “invigorating and pungent” vegetables, like onions, garlic, and bulbous roots, for the overly “solid nourishment” they provide. Here we find echoes of the ancient distrust of root vegetables. We also must avoid all dry fruits, nuts, and the hardest seeds. That leaves around forty vegetables, which Cocchi does not identify but which are “normally cultivated amongst us in our fields and gardens; and those which are the most common, are also the most wholesome.”

Few physicians were willing to go as far as Cocchi. The problem with vegetables, argued Cocchi’s contemporary Giuseppe Antonio Pujati, was that they were too easy to digest. That is, they were expelled from the body so easily that they provided little nutrition. An exclusively vegetable diet, such as that of the poor forced to subsist on wild plants, resulted not in better health but in intestinal problems, vomiting, and diarrhea. Consequently, Pujati concluded that vegetables should be considered as “correctives” to meat and other dishes and not nourishing foodstuffs in their own right.

The problem was that “a vegetable diet renders man gentle and pleasant in nature,” which we might think was good. But someone had to grow these vegetables, and paradoxically, the enforced “Pythagorean regimen” of Italy’s peasants made them “weak and incapable of great labors.” It was one link in a chain that had resulted in the “decline of agriculture.”

Historians always have difficulty finding information relating to the diet of the poor. Luckily, when the kingdom of Naples (southern Italy) came under the rule of Napoleon, the French investigated local economic and social conditions. Their resulting report, the Statistica murattiana, covers the years 1807 to 1811. (If it means jumping ahead a few decades in our account, it is certainly worth it, given the source’s wealth of information. In any case, most of the investigation’s findings can be projected back a generation to the late eighteenth century.) The Statistica was based on similar projects elsewhere, following the installation of Napoleonic governments in much of Italy, as well as on inquiries carried out in France. Each of the Neapolitan provinces had a local editor, who usually was a reform-minded physician, lawyer, or agronomist responsible for circulating the questionnaires, assembling the findings, and returning them to Naples. Answers to the questions relating to the local diet and the rural economy provide some fascinating insights into the condition of the local populations throughout southern Italy. Here much of the population not only ate vegetables but even subsisted on them, and here the tomato first became an important part of the local diet.

The editor for the province of Abruzzo Ulteriore remarked that “the tendency toward a vegetable diet depends very often on habit and poverty, which obliges people, reluctantly, to turn to whatever food they can most easily procure.” Wild plants were eaten everywhere. In the words of the compiler for the province of Molise,

Generally, green soup [la minestra verde] is the ordinary food of a peasant family. It is often composed of wild edible plants. … They are boiled in water, seasoned with oil or pork fat, salt, pepper, or ground chilies. This food is good for health and costs nothing; one girl can gather in three hours in the countryside enough for a family of five.

The editor for Abruzzo Citeriore took a different view, bemoaning the overreliance on “field vegetables,” which were not always properly seasoned and contributed to “weakness, cachexia, dropsy, putrid fevers and other epidemic diseases, as was sadly experienced in the year 1803.” Most compilers concurred.

In Capitanata, the peasants ate something they “call acqua e sale and bread cooked in oil, and very often they mix wild plants in with it.” Acqua-sale was the name given to a dish eaten in Puglia, Basilicata, and Calabria, in which stale bread was moistened with water and oil, and then mixed with some salt and vegetables like garlic, onion, celery, sweet peppers, and, as they became more widespread, tomatoes.

The Statistica gives the impression of a southern Italian peasant diet that is full of variety. But this variety had its limitations. First, it was a diet largely limited to vegetables, accompanied by bread made largely from inferior cereals. Second, as a result, it was also highly seasonal, which explains the importance to the domestic economy of preserving foods for use throughout the year (to which we shall return in chapter 4). Third, given the nature of the source, the Statistica tends to record peasants’ production rather than consumption. Much of this “variety,” therefore, was actually cultivated to be taken to market and sold, not eaten. Finally, methods of preparation remained basic because the kitchen utensils remained basic. The peasant kitchen thus was simple, with only a few clay or wooden implements. In contrast, the better-off kitchen was increasingly stocked with a wide range of utensils for the preparation and preservation of foods.

On a more positive note, the Statistica shows traces of an appreciation for vegetables shared throughout society. Francesco Perrini, a cathedral canon and the compiler for the rich agricultural province of Terra di Lavoro, was a real vegetable enthusiast. Perrini goes out of his way to praise the two different varieties of fennel from the towns of Sora and Nola, the onions of Mondragone, the cardoons of Cerreto, the cauliflowers of Matese, the white radishes of Aversa, the ball lettuces of Sant’Angelo, the head cabbages of Santa Maria, and the chilies of Maddaloni. This was the hinterland of Naples, so supplying the city with these products made a significant contribution to the local economy.

Perrini even extensively details how different vegetables were consumed. His list includes important New World products. One of them has been mentioned, the chilies of Maddaloni. The variety grown, baccato (Capsicum baccatum), produced a “small, red fruit, but of an insufferable pungency,” Perrini noted. The chilies were used to season eggplants: “Ordinarily [eggplants] are served boiled, sliced and then cured with the strongest vinegar possible, to which is added a dose of baccato chilies, oregano, and slivers of bruised garlic, called by the local name of impepata or molignanelle.” Eggplants were also eaten fried, although the well-off preferred them stuffed. Some varieties of peppers—the long “common” pepper and the yellow bell pepper—also were eaten as vegetables. Perrini describes that they were “cooked in the ashes, raw and fried, or in salads or cured in vinegar so they can be kept for the whole year.”

Even the potato had made limited inroads, Perrini was pleased to report, among the inhabitants of the Apennines. These mountain dwellers ate them seasoned “with oil, pork fat, cooked grape must, or salt and prepared different dishes with them.” This comment should be seen in the context of a long campaign by reformers throughout Europe, begun in the eighteenth century, to have the potato adopted as a staple crop as a means of combating hunger and famine.

But among all these favored foodstuffs was one plant that, despite having no government backing, was destined to have the greatest impact on the future of Italian cookery: the tomato.