At the beginning of 1849, the Tuscan innkeeper Luigi Bicchierai, “Pennino” to his friends, noted the following in his commonplace book:

With all these rebellious uprisings and the desire to create Italy, I, who am an innkeeper and know little of such things, have thought about Italy so divided but which everyone wants, including me; and I imagine it like a lovely pot of boiled meats: trotter, tongue, various cuts, and seasonings! And so, if Italy is a bollito, its flag should be the condiment for it, in other words, the “Tricolor Sauce.”

Bicchierai goes on to provide the recipe for this patriotic sauce of his own invention, in the colors of the flag—green, white, and red—proposed for a united Italy. It consists of three separate sauces. The salsa verde is a mixture of finely chopped capers, anchovies, hard-boiled eggs, basil, parsley, onion, and garlic, moistened with olive oil and wine vinegar. It was (and is) found in many regions of Italy as an accompaniment to mixed boiled meats (bollito misto). The salsa bianca is a simple béchamel sauce, but it is Bicchierai’s salsa rossa, you will have guessed, that interests us most.

Bicchierai’s “tricolor sauce” is an appropriate way to start this chapter on the nineteenth century. In Italy, the nineteenth century was shaped by the movement to unify the different states of the peninsula and islands into a single great nation, the Risorgimento. By 1861, the process was largely completed, although parts of the Papal States, and Rome itself, were not annexed until 1870. More important, this was the century when pasta and tomato sauce were fatefully combined to create pasta al pomodoro.

Salsa rossa (Red sauce)

The last color of the [Italian] flag, the salsa rossa: Put in a pan seven or eight large tomatoes, chopped; one-quarter onion; two basil leaves; a stick of celery, finely chopped; and a little parsley. When the tomatoes have lost much of their liquid, strain everything through a sieve; pour this passata into a pan; add a spoonful of [olive] oil, a pinch of salt, and a small pinch of pepper; and bring it to a boil, occasionally stirring it. The lovely red sauce is ready. If you want it sweet-and-sour, all you have to do is stir in a large spoonful of [wine] vinegar and a small spoonful of sugar before removing the pan from the fire; taste; and add more vinegar or sugar if necessary.

Luigi Bicchierai, Pennino l’oste, ed. Franco Tozzi (Signa: Masso delle Fate, 1996), 105–6.

On July 26, 1860, commenting on the project to unite Italy, one of its proponents, Camillo Benso, count of Cavour, wrote in a kind of ironic code and in French that while “les oranges [the Sicilians] … sont déjà sur notre table,” “les macaronis [the Neapolitans] ne sont encore cuits.” The Sicilians, in other words, were ready for Giuseppe Garibaldi’s expedition and eventual annexation to a united Italy, under King Victor Emanuel of Savoy. But the Neapolitans, “the macaronis,” were not. Naples already was synonymous with pasta, especially dried pasta made from durum semolina wheat, known simply as “Naples pasta” (pasta di Napoli) or “Neapolitan macaroni” (maccheroni napolitani). The House of Savoy may have conquered Naples in the nineteenth century, but the consumption of Neapolitan-style pasta would conquer all of Italy by the late twentieth century.

To understand the significance of the encounter between pasta and tomato—the how, when, where, and even why of how this classic combination originated—we must look briefly at the history of pasta in Italy. We do not have to bother with the debates about who invented or discovered pasta. In fact, pasta, in the sense of any product made from a dough made from mixing wheat flour (hard or soft, with the bran removed) and water (or eggs), has been found at many different times and in many places, from the Mediterranean to China. Suffice it to say that various forms of pasta were well known in Italy by the time the tomato first appeared in the mid-sixteenth century: lasagne, vermicelli, maccheroni, to name only the main types.

This pasta was very different from what we have today. First, it was eaten soft. Since the Middle Ages, pasta had been cooked for long periods—half an hour, an hour, even two hours—generally in broth, until it was soft and “melting” (fondente). This was the standard way of cooking both fresh and dried pastas, which conformed to then current notions of taste and health. Second, because pasta was served moist, it usually was accompanied by dry condiments, and it was seasoned in different ways, “whether with oil or walnuts or almonds, or with milk or cheese, or with pepper or other spices,” in the words of Costanzo Felici. Only pork fat is absent from Felici’s list. Third, pasta was not yet eaten as a dish in its own right—as a first course, say. Instead, it was served as a side dish (for example, to accompany meat) or as a dessert.

Travelers visiting in Italy were often struck by the place of pasta in the Italian diet. John Ray, one of the first Englishmen to observe personally the Italian consumption of the tomato, described the use of pasta in some detail. Note that he uses the term pasta in the generic way we use it today:

Paste made into strings like pack-thread or thongs of white leather (which if greater they call Macaroni, if lesser Vermicelli), they cut in pieces and put in their pots as we do oat-meal to make their menestra or broth of, much esteemed by the common people. These, boiled and oiled with a little cheese scraped upon them, they eat as we do buttered wheat or rice. The making of these is a trade and mystery [organized craft]; and in every great town you shall see several shops of them.

By the time of Ray’s visit, pasta was being made throughout the Italian peninsula and islands, usually in the vicinity of flour mills and bread bakers. Pasta makers had been granted their own guilds, independent of the bakers’ guilds, in cities like Naples, Palermo, Genoa, Savona, and Rome. Strangely, Sardinia is absent from this list, even though the pasta of Cagliari already had a favorable reputation. Otherwise, the establishment of guilds reflects the regionality of pasta making, and all these areas became famous for their production as the industry continued to grow.

The two best-known areas of production were the Ligurian coast from Genoa southward and the Bay of Naples and Amalfi coast. Entire towns were devoted to making pasta. The Ligurian town of Port Maurizio (today’s Imperia) had forty pasta manufactories by the beginning of the nineteenth century, supporting two hundred families. In the vicinity of Naples, places like Torre Annunziata, Gragnano, and Castellammare, already the location of numerous mills, effectively became one-industry towns. By 1633, the Naples region was already exporting more than 140cantaia (some 30,000 pounds) of pasta.

The specializations of the two regions, Naples and Genoa, were quite different from each other, at least in the minds of contemporaries. When François Chapusot, chef to the English ambassador at the Savoyard court in Turin, prepared macaroni, he used only that imported from Naples. “It is generally the best, both for the chosen quality of wheat that is employed, and also because it can be boiled without breaking up into pieces,” Chapusot wrote. But when choosing finer and smaller pasta shapes for soups, he preferred pasta from Genoa.

By the seventeenth century, the teeming metropolis of Naples already was identified with pasta production and consumption, and the city’s guild of vermicelli makers (Vermicellari) dates from at least 1546. The vermicelli makers joined the new guild of macaroni makers (Maccaronari) in 1699, a trend exemplifying how the term maccherone came to stand for all forms of pasta. The Frenchman Jérôme de Lalande, traveling in Italy in the 1760s, differentiated more than thirty pasta shapes being made in the Naples region, as well as listing the various presses and cutters used to make them.

Pulcinella, a comic theater character associated with Naples, was constantly depicted eating pasta (figure 16). In a 1632 commedia dell’arte play, Silvio Fiorillo has Pulcinella condemn the city’s overlords (portrayed by a Spanish soldier) with the words: “Ah, Spaniard, enemy of macaroni,” as if to say, the enemy of the Neapolitans themselves. When the ever famished Pulcinella dreams at night, he tells Clarice, with whom he is in love,

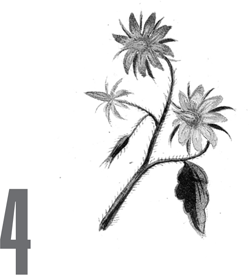

Figure 16 Giuseppe Garibaldi’s small force routs the army of Bourbon Naples—depicted as a mass of feckless, macaroni-touting Pulcinellas—in Cabrion’s [Nicola Sanesi] “Attualità: L’ultimo Atto di un Dramma!” (Current Affairs: The Play’s Final Act), published in the satirical newspaper Il Lampione, September 4, 1860, 3.

I dream—oh, love and what it does!—of a big dish of macaroni with meatballs on top. I reach out my hand, grab hold of the macaroni and meatballs, I season them, I mix them up, and when I go to put them in my mouth, I wake up all in a huff … with passion in my heart I start weeping like a child.

A French visitor to the city recorded a play in which Pulcinella, having become king, was told that he would have to give up his macaroni, as it was considered too plebian. To this Pulcinella replied, in Neapolitan, “Mo mo me sprencepo” (“Then I resign, effective immediately,” or words to that effect).

In Naples, freshly made pasta was laid out on cane racks or large cloths to dry in the sun. If this seems like an intriguing parallel to drying tomatoes, remember that drying and salting were the main methods of preserving food. Drying pasta was actually a complex process, with three drying phases of different duration according to the shape of pasta and the weather. The method was perfectly suited to Naples’s temperate climate. It was said that pasta should be made when the warm, humid southerly wind blew and be dried when the drier and cooler northerly wind blew (i maccheroni si fanno col sirocco e si asciugano con la tramontana). As a result, the process was almost impossible to duplicate elsewhere in Europe.

By the 1790s, the elites of Italy were eating maccheroni napoletani on special days, some as part of the “first course,” which itself was a recent innovation, since previously the dishes had been served at the same time. At the Milano-Franco household in Polistena (Calabria), “upstairs” might have a dish of marmitta di maccaroni, plus various other dishes; and “downstairs” had simple macaroni, soup, and boiled meat. The servants were not eating pasta as a separate course yet, but they certainly were eating it.

According to the Statistica murattiana of 1811, the better-off of Potenza (Basilicata) ate pasta brought from the Amalfi coast, south of Naples. The poor, by contrast, either made their own or bought it at half the price from the local maccaronari, “who make it badly.” For southern Italian peasants, pasta was a holiday luxury, not an everyday staple. Nonetheless, it had become the “symbol of joy and abundance,” according to the compiler of the Molise submission for the Statistica. The different seasonings they used reflect an almost medieval mixture of sweet and savory: “Rarely do the people season it with cheese, but with oil, pork fat, or else with vinegar or cooked grape must.”

For more affluent people, pasta was fast becoming an everyday food, beginning in the grain-producing regions of the south. Religious institutions, like aristocratic households, would sign annual contracts with local pasta makers, who supplied them regularly for a fixed price. In 1817, the ten Franciscan friars at the monastery of San Matteo, in San Marco in Lamis (in the grain-rich plain around Foggia, Puglia), managed to eat their way through 392 pounds of maccheroni, 353 pounds of maccheroncini, 71 pounds of pasta fina, 11 pounds of vermicini, and 9 pounds of punta d’ago. Although these are different forms for different uses, these figures work out to roughly a dish of pasta (3.7 ounces) a person per day. Female religious ate large quantities too, but in more elaborate forms like gnocchetti, taglioni, rafaioli, and egg pasta. According to the form of pasta, it was eaten with vegetables, in broth, seasoned with lardo (hard bacon fat) or cheese, or, on special occasions, with a tomato-less veal ragù. Nuns tended to make their own, and some convents became well known for their handmade pasta.

Pasta triumphed in nineteenth-century Naples. At the time of Italy’s unification, Neapolitans were great consumers of pasta, locally made and of excellent quality, according to Achille Spatuzzi and Luigi Somma, the two Neapolitan doctors quoted in chapter 3. Even the poor could afford to eat pasta, although they had to make do with the so-called minuzzaglie, the damaged bin-ends of different pasta shapes and sizes, at a time when pasta was still sold loose.

By the mid-nineteenth century, pasta was eaten in taverns served with a meat or tomato sauce and topped with grated hard cheese. According to Carlo Tito Dal Bono’s “Le taverne” (1858), a description of Naples’s taverns, the macaroni eater “enjoys a meat sauce, but the tart tomato is perhaps equally pleasing, and where one or the other is absent, he sticks to the purest simplicity, of cheese alone.” Pasta was eaten in the backs of shops by shopkeepers supplied with ready-made portions by the city’s macaroni makers and sellers. In 1845, Naples had 280 maccaronari.

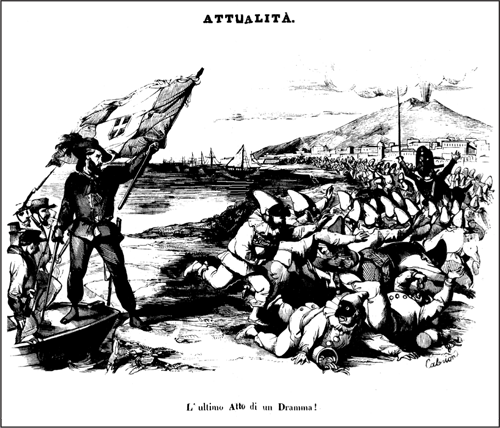

It was as street food that pasta came into its own. While visiting the city in 1787, Goethe commented: “The macaroni … can be bought everywhere and in all the shops for very little money. As a rule, it is simply cooked in water and seasoned with grated cheese.” Pasta was consumed primarily in the open, bought cheaply from stalls in the streets and markets equipped with boiling cauldrons, where it was quickly seasoned and consumed, using the hands, as depicted in the inexpensive “genre” prints of the time and (later) picture postcards for tourist consumption (figure 17). The Neapolitan journalist Matilde Serao described the scene in Il ventre di Napoli (1884):

As soon as he has two cents, the Neapolitan pleb buys a dish of macaroni, cooked and seasoned. All the streets of the city’s popular quarters have one of these taverns that set up their cauldrons outside, where macaroni are always on the boil, with pots of simmering tomato sauce and mountains of grated cheese… . This setup is very picturesque, and a few painters have painted it … and in the collections of Neapolitan photographs that the English buy, alongside the lay nun, the petty thief, the flea-ridden family, there is always the macaroni seller’s table.

This kind of “street food” approach to the preparation and consumption of pasta was probably responsible for another important development: an appreciation of eating the pasta still slightly hard, not completely cooked. This was a novelty. The new Neapolitan practice particularly suited the local pasta, which was made from durum wheat and dried, as it allowed it to keep its elasticity and slightly chewy consistency. Writing in Cucina teorico-pratica (1837), his guide to Neapolitan “home cooking,” Ippolito Cavalcanti, duke of Buonvicino, insisted that the macaroni be cooked only until vierd vierd, a Neapolitan expression meaning “slightly hard” (literally, “very green”). After Italy was unified, this practice spread to the rest of Italy. In a cookbook to which we shall return later in this chapter, Pellegrino Artusi advises that “as for the macaroni themselves, the Neapolitans recommend that they should be boiled in a large pot, with lots of water, and not cooked too long.” The pasta shapes should be cooked “fairly hard” (durette). Paradoxically, and defying the dietary advice of previous centuries, this actually makes pasta easier to digest. As Artusi explained, the slight hardness requires that it be chewed before being swallowed. But he does not call this consistency al dente, that untranslatable expression referring to this brief cooking. That expression did not become common in Italy until after World War I.

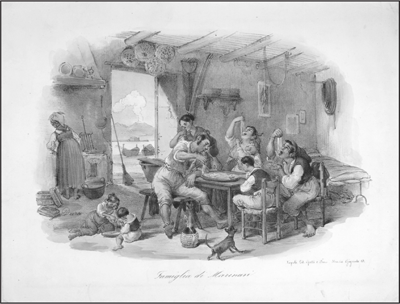

Figure 17 Gaetano Dura, Mangia Maccaroni (Macaroni Eaters) (above) and Famiglia di Marinari (Family of Sailors) (below). From a series of lithographs depicting popular Neapolitan scenes, printed by Federico Gatti, Naples, ca. 1840. (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The gradual industrialization of pasta making in the second half of the nineteenth century helped turn it into a staple. How does pasta making compare with tomato production? Whereas pasta making was an Italian—especially a Neapolitan—success story, food preservation remained a mainly domestic or cottage industry well into the twentieth century.

The simplest method of preserving tomatoes was hanging the entire plant before it had ripened. The tomatoes would gain in sweetness over the following months and could be used “fresh” during winter. A manual on vegetable cultivation published by the horticulturalist brothers Marcellino and Giuseppe Roda, Manuale dell’ortolano contenente la coltivazione ordinaria e forzata delle piante d’ortaggio (1868), noted that people saved healthy, but still partially green, tomatoes in the autumn, which soon became a common wintertime decoration for rafters and walls. In the words of Marcellin Pellet, the French consul general in Naples, writing in 1894: “The diet [of the inhabitants] is essentially vegetable. On the walls of houses, on either sides of the windows, one sees hanging long bunches of tomatoes, onions, poles of prickly pears [a kind of cactus with edible fruits].” Particularly suited to this practice were the small, firm, thick-skinned tomato southern varieties like ‘Principe Borghese’, which dates from this period.

Next in the hierarchy of complexity was halving, salting, and drying the tomatoes, a method first practiced in Sardinia. But more commonly, the fresh tomatoes were transformed. According to the Roda brothers, they were turned into a pasta (paste), “like a soft polenta,” by extended simmering and then straining. This paste could then be dried on boards in the sun for three or four days and then rolled flat, to produce a more concentrated conserva nera (the older method we encountered in chapter 3). Or the paste could be bottled, without further drying. The bottles would be sealed and boiled in a bain-marie, according to the Appert method. The Rodas favored the second option, “since the paste maintains its lovely original color in the bottles, with a flavor not dissimilar from the fresh fruits.” This is today’s passata, in the sense of having been “passed” through a strainer, although early-twentieth-century manufacturers sometimes called it salsa.

For much of the nineteenth century, preserving tomatoes remained a small-scale, local activity that was closely linked to domestic agricultural production. At this time, the agricultural sector dominated the young nation’s economy, employing seven out of ten people at the time of Italy’s unification in 1861 and even still employing half of all workingmen and -women on the eve of World War II. Dietary practices were dictated by necessity and the need to economize. At the end of the nineteenth century, food accounted for around 75 percent of rural and urban working families’ living expenses, a figure that did not dip below 50 percent until the early 1960s.

Preserving tomatoes was important in symbolic terms, too. In Giovanni Verga’s realist novel I malavoglia (1881), Rosolina’s conserva dei pomidoro crops up throughout the novel, like a refrain echoing the decline of the family at the heart of the book. Indeed, food imagery and references permeate Verga’s novel. Although the foods are basic, the language is rich in sayings, proverbs, and metaphors and is accompanied by Verga’s use of repetition and leitmotiv, capturing the flow of life and the passage of time.

Near the beginning of I malavoglia, the unmarried Rosolina boasts to her brother, a priest, of her skills as a housekeeper. This includes “the tomato purée to make; that she knew a special way of making it that kept it fresh right through the winter” (chapter 4). Halfway through the book, some women are having an animated discussion “while Rosolina was cooking her tomato purée, her sleeves rolled up” (chapter 10). Later, thinking that a certain Don Michele is interested in her and that he will walk by her house just to catch a glimpse of her, Rosolina “was perpetually busy on her balcony with her tomato purée or bowls of chilies, to show what she was capable of ” (chapter 13). But Don Michele is not interested in her, another woman says: “Donna Rosolina can make eyes at him from her balcony until she takes root among her tomatoes, for all the good it will do” (chapter 13).

At the end of the book, with the Malavoglia family utterly ruined, Rosolina is in a bad way as well:

And Donna Rosolina had lost weight through bad temper, especially after Don Michele had gone away and all his misdoings had come to light. Now she did nothing but go about in search of masses and confessors, here and there, as far as Ognino and Aci Castello, and she neglected her tomato purée and tuna in oil, to dedicate herself to God. (chapter 15)

Verga singles out Rosolina’s isolation from the start of the book when she is making conserva on her own. By the time Verga was writing, though, its preparation was very much a group ritual. The French archaeologist and antiquarian François Lenormant, traveling through Catanzaro (Calabria), was struck by the “enormous pyramids” of tomatoes at the town’s market. Captivated, Lenormant had this to say about the domestic preparation of tomato preserve:

We are, in effect, in the season in which, in every Calabrian house, tomato preserve is made for use during the rest of the year. It is a solemn occasion in the popular life of these lands, a kind of festive celebration, an excuse for get-togethers and gatherings… . Neighbors, and especially the neighborhood women, get together in different houses one after the other for the making of conserva di pomi d’or, a procedure that culminates with a large meal; and they gossip as much as they can while crushing and cooking the tomatoes. It is here that for several months the locale’s chronicle of scandal is identified and commented on; it is here that those old rustic songs, which are today so avidly collected by scholars keen on folklore, are repeated from generation to generation.

A new ritual, based around a new foodstuff, thus took on an old form.

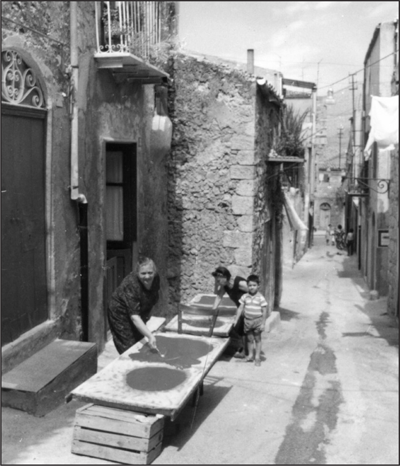

Sicilian families soon carried across the Atlantic the process for making what they called astrattu (extract) (figure 18). This process was described by Carlo Levi, a Turinese sentenced to “internal exile” in Basilicata in 1935/1936. Even though it may be unappetizing, Levi conveys the scene as if in a still-life painting, which was no coincidence, given that Levi was also an artist:

Out on the street, in wide-rimmed tables below the black pennants decorating the front doors, blood-red liquid masses of tomato conserve lay drying. Swarms of flies walked without wetting their feet over the portions already solidified, in numbers as vast as those of the children of Israel, while other swarms plunged into the watery Red Sea, where they were caught and drowned like Pharaoh’s armies as they hotly pursued their prey.

Figure 18 The drying phase in the preparation of traditional tomato paste (astrattu) in Canicattì, Sicily. (Photograph by Diego Sgammeglia, courtesy of Alfonso Messina)

In the early twentieth century, the inhabitants of the malaria-ridden countryside south of Rome even resorted to removing and using as strainers the window screens that the health authorities had installed to keep out the mosquitoes, a sign of the peasants’ mistrust of the medical authorities, to say nothing of the importance of tomato conserva to their diets.

The making of tomato conserva, in large vats left out in the sun and stirred from time to time to mix the slowly thickening tomatoes (and to chase away the flies), was also a feature of urban balconies. In Racconti napoletani (1889), Serao describes the “acrid smell of tomato conserva” coming from the balconies of the “vicoletto delle Gratelle” in Naples’s dense network of narrow, ancient streets. The sun did the work of cooking over the fire in condensing the tomato sauce into a purée, which might then be formed into loaves or bottled for storage. Indeed, tomatoes were preserved in the form of paste “in great abundance” in the city and, from at least the 1860s, widely consumed, according to the Neapolitan doctors Spatuzzi and Somma.

Dried tomato conserve, paste, concentrate, or extract was not made only in the south. In 1849, Heirom Aime, the American vice-consul, found it in the Ligurian port of La Spezia, available in a form resembling “a large Bologna sausage.” He saw a great economic potential in its manufacture and sale in the United States. In Genoa, the tomato conserve, “sufficiently stiff to stand in conical forms, as loaf sugar,” was sold in food shops, brought in from the surrounding countryside by the wagonload. Less than forty years later and despite the absence of a long-standing craft tradition behind it, the preparation of tomato conserva did become a “profitable agrarian industry” in Liguria. The Jacini Parliamentary Inquiry of 1878, on the state of Italian agriculture, found that large quantities of the tomatoes grown around the town of Albenga—ancestors of today’s large, segmented oxheart variety—were sold outside the region. As early as May, fresh tomatoes found their way by rail to the markets of Piedmont and beyond, and tomatoes later in the season were turned into paste. In fact, eight hundred to one thousand, 132-pound barrels of tomato paste were exported each year, mostly to the United States.

From its origins as a cottage industry, the preparation of conserva dell’estratto di pomodoro on a more industrial scale became concentrated (sorry!) where tomato cultivation was most extensive, along the Ligurian coast, in Emilia Romagna (around Piacenza and Parma), and in Campania (around Salerno and Naples).

Drying was still, however, the most common method of preserving tomatoes. Tomatoes were usually dried into a paste in the countryside where they were harvested. Thus it was unfortunate that they were poorly presented in the markets, opening them to competition from Portugal, Greece, and Turkey. This was an especially sad outcome for southern Italy and Sicily, where consumption was highest. Only two artisans from the Tuscan town of Castelfiorentino succeeded in making a product that was pleasing to the judges. This consisted of tomatoes “condensed into thin, translucent sheets, and of pleasant color and agreeable taste.” Ten years later, the mayor of Miglianico (Abruzzo) presented his town’s tomato conserva to a national parliamentary inquiry on industrial production. Before this, all its conserva had been consumed locally, the mayor said, but he hoped to organize its export. In 1879, Andrea Vivenza, an Abruzzese agronomist-physician, even wrote a treatise on the preparation of tomato preserve.

Other preserving methods were suggested. A successful Neapolitan cookbook, La cucina casereccia (1816), recommends preserving tomatoes by putting them in jars and covering them with brine, but this method never really caught on. Even though the acidity of tomatoes would have made them easier and safer to preserve than many other fruits and vegetables, it was another hundred years before canning whole tomatoes became commonplace.

Initially, the food-preserving industry did not consider canning tomatoes to be worthwhile or even technically possible. Meat, however, was canned, primarily for use by the military, as were more expensive vegetables, like peas, which had a short growing season. Preserving vegetables and fruit on an industrial scale then began in earnest in the mid-nineteenth century in Britain, the United States, and Germany. Tin cans replaced glass bottles and jars, as they were cheaper to produce and protected their contents from the light. At this time, Italy did not have much of a food industry. Preserved food products were limited to the cured meats of the center and north and the dried fruits of the south, but these were more small-scale rural domestic products and urban artisan manufactures than an industry as such. The Cirio Company, which later came to dominate the Italian production of preserved tomatoes, was still involved mainly in the export of fresh produce, using the newly laid railways. Cirio’s forays into food preservation were limited to canning peas, asparagus, artichokes, peaches, and pears, for which there was a great demand. Nevertheless, the company was considered important enough for a government decree in 1885 allowing Cirio train cars to be painted with the red, white, and green of the national flag.

Tomatoes were first canned in the United States and Britain, as the food historian Andrew Smith recounts. In 1847, Harrison Crosby of New Jersey filled tin pails with whole tomatoes, boiled the pails, and sealed the top of each with a tin disk. Packed six pails to a box, Crosby sold them in New York and, to drum up business, sent samples to Queen Victoria and President James Polk, as well as to local newspapers, restaurants, and hotels. By the 1860s, one canner in New Jersey, employing thirty people, produced 50,000 cans in a single season. Consequently, by the 1870s, canning tomatoes had become big business in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and by 1879 more than 19 million cans of tomatoes were being produced each year. Soon this figure had risen fourfold, and within a few years, more tomatoes were being canned than any other fruit or vegetable.

The first attempts at canning tomatoes in the newly unified Italy were nothing short of disastrous. A sample of tomato extract prepared according to the Appert method and shown at the first Italian national exhibition, held in Florence in 1861, was judged to have an “empyreumatic” taste. In other words, it had been burned. The hygienist Adolfo Targioni Tozzetti, the third of a Tuscan dynasty of naturalists and the author of a report dealing with diet and health, regarded the preservation of food as a national necessity, but he disapproved of using the Appert method of preservation.

At the same time, tomato ketchup had been proclaimed the national condiment of the United States. Early versions of tomato ketchup usually were simply boiled, reduced, and strained tomatoes to which a few spices had been added. It was used as a condiment with meat and fish or added to other sauces. Thus ketchup was not unlike the tomato coulis and purées found in the Italian cookbooks of the same period. Industrially produced ketchups, however, added ingredients like sugar, increasingly common in American cooking, as well as the more traditional vinegar and salt. After a shaky start, by 1899 the H. J. Heinz Company, based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, had opened branches in London, Liverpool, Antwerp, Sydney, Bermuda, Mexico City, Toronto, and Montreal, on course to becoming the world’s largest ketchup producer and constructing the world’s largest preservation factory.

Ketchup, in the form of “Beefsteak ketchup,” was then also made and sold by the Joseph A. Campbell Preserve Company, which manufactured canned tomatoes, vegetables, and, of course, soups. Its real success began in 1897 when the company developed a process for condensing its tomato and other soups. This, in turn, reduced production and shipping costs, and the lower prices were passed along to consumers. This, and a shrewd marketing campaign—which included recipe booklets and meal planners—made Campbell’s soup a household name. And in 1912, Campbell’s began to provide tomato farmers with seeds specially developed by the company.

Fresh tomatoes were being transported greater and greater distances by railway throughout the United States. When cultivation and consumption began to take off in the second half of the twentieth century, new varieties were developed to meet the increasing demand, with some developed specifically by and for the food industry. By the 1860s, American seedsmen had available more than twenty varieties, although we do not know exactly what they looked (or tasted) like. In Ohio between 1870and 1893, Alexander Livingston developed or improved thirteen major varieties for the tomato trade. He named most of them after himself, such as ‘Livingston’s Marvel’, ‘Livingston’s Magnus’, ‘Livingston’s Paragon’, and ‘Livingston’s Perfection’. Some of these varieties eventually found their way to Parma, Italy, suited as they were to the production of concentrate. In this guise, the tomato thus crossed the Atlantic a second time—before the finished product was exported back again.

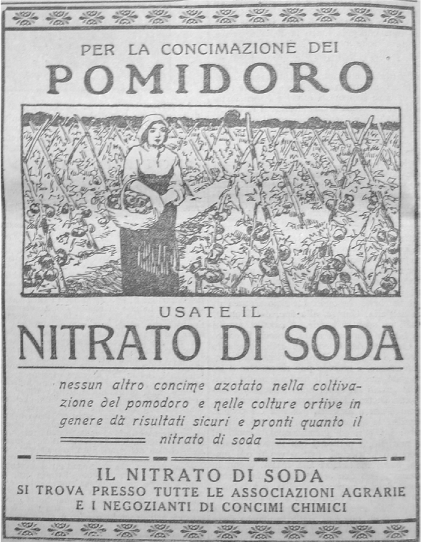

State-run experimental farms, government agencies, and agricultural schools became interested in the fledgling tomato industry. Articles in the journal issued by the school at Portici, near Naples, suggest that beginning in the 1880s, agronomists became increasingly interested in the tomato, an interest that was as much technological and industrial as it was agricultural. In Brescia, the agronomist and priest Giovanni Bonsignori realized that for a farm to be a success, produce and processing had to be closely linked. In charge of the Istituto Artigianelli, an agricultural school for boys, Bon-signori began to grow tomatoes at the school’s farm in Remedello Sopra. “Large-scale tomato cultivation [will start] the industrial processing of which is to be undertaken by a plant now being built in town, capable of processing any quantity of tomatoes.” So promised Bonsignori in a speech delivered in January 1899. Later that year, Bonsignori wrote to the farm manager advising him on the use of fertilizers like nitrate of soda, ammonium sulfate, and bone phosphate on the 9 piò (7 acres) of land set aside for tomatoes. Nitrate of soda in particular, massive amounts of which were imported each year from Chile, had a long history in agriculture, and today, organic growers still are permitted to use it (figure 19).

Figure 19 “To fertilize your tomatoes, use nitrate of soda,” recommends an advertisement published in the newspaper Corriere della Sera, April 19, 1913, 4. Note the large ribbed tomatoes favored by northern Italian growers, staked on sets of canes.

At first, things went well in Remedello Sopra. By 1900, the second year of its operation, the processing plant was producing some 200,000 cans of tomato concentrate for export, and other estate owners in the area were persuaded to grow tomatoes and send them to Remedello Sopra for processing. Then in 1904, tomatoes no longer appear as an entry in the school farm’s accounts. Why was the experiment, which had seemed so promising, abandoned after just a few years? No reason is given, but as Bonsignori himself wrote in La coltivazione del pomodoro (1901), “Tomato cultivation, while possible in all the regions of Italy, is more successful in sunny places than in those areas infested by fog and cold.” Perhaps Bon-signori had his native Brescia in mind.

One of the “sunny places” was Parma. The area was, and is, justly famous for its ham and cheese. Less well known is its important place in the cultivation and preservation of tomatoes, which was largely the work of one man, Carlo Rognoni. Rognoni was a local landowner and professor of agronomy who decided to experiment with tomatoes after wheat prices fell in the 1880s. He succeeded where Bonsignori failed, overcoming local resistance to cultivating tomatoes and arguing that they could be successfully grown in the Po valley. So Rognoni inserted tomato cultivation into the preexisting cycle of crop rotation, along with careful irrigation and fertilization. Tomato cultivation in Parma also benefited from cheap seasonal labor and piecework, whose dramatic consequences we shall see in chapter 6.

On his own experimental farm, Rognoni tried out different tomato varieties—the preference was for larger fruits—and growing methods. This included the use of extensive staking to support the plants, which was able to dramatically increase yields. (Self-supporting, determinate plant varieties became available only after World War II, when they were imported from the United States.) The expansion of tomato cultivation throughout the province of Parma was accompanied by the development of tomato processing. Then, late in the century, the traditional drying of tomato paste into loaves—the conserva nera—was replaced by the bottling of tomato concentrate.

During the nineteenth century, bottling tomato concentrate remained a small-scale industry, both localized and marginalized. It was localized because Parma’s producers were based at their production sites, close to the tomato fields, as many of the producers also were tomato farmers. The techniques used were essentially those of domestic production, albeit on a larger scale and using simple machines. The bottling was marginalized because at the International Exposition of 1889 in Paris, the few producers of conserva in the Italian pavilion found themselves dwarfed by the producers of other preserved foods. But tomatoes were not preserved at an industrial level until the twentieth century.

In 1891, however, Pellegrino Artusi offers us a tantalizing glimpse of the future. In his recipe for “saltless tomato preserves” (conserva di pomodoro senza sale), he refers to a new “procedure known as vacuum packing, in which you preserve fresh whole tomatoes in tin cans.” He describes the production recently begun in Forlì (Emilia Romagna), which flourished at first. “Alas,” Artusi concludes, “the treasury immediately slapped a tax on it, and the poor owner told me that he was thinking of closing down.”

We have traced the development of the pasta-making industry and looked at tomato preserving. When did the two finally come together?

How and when the tomato-as-condiment was first put on pasta is a mystery. The first mention of using tomatoes in a pasta dish is actually French. In L’Almanach des gourmands (1807), Alexandre-Balthazar-Laurent Grimod de la Reynière recommended that in the autumn, tomatoes be substituted for the purées and cheese usually mixed into vermicelli before serving. He justified this practice by noting that “the juice of this fruit or vegetable (however one defines it) gives a rather agreeable acidity to the soups into which it is put, which is generally pleasing to those who have become accustomed to it.” Using tomatoes in soups was a long-standing practice in Italy, as we saw in chapter 3, as Grimod would have known. But by Grimod’s time, tomatoes also were consumed in Paris, as by then they had made the journey northward from Provence. Indeed, it is Provence that gives us the proverb “It is the tomato that makes a dish good” (Poumo d’amour que’es bono viando), advice that was about to be taken in various parts of Italy.

The marriage between pasta and the tomato is usually said to have taken place in Naples. La cucina casereccia, referred to earlier, has a recipe for maccheroni alla napolitana, in which the pasta is boiled in a meat broth in which tomatoes have been cooked. The cookbook is very enthusiastic about tomatoes, as we would expect, given its place of publication. Other uses of tomatoes, either fresh or preserved, are in meat stews and soups, with boiled meats and omelets, and as a filling for potatoes.

The recipe for maccheroni alla napolitana is not a tomato sauce. It was not until 1837 that Cavalcanti wrote that the secret of a successful dish of baked vermicelli with tomatoes (timpano di vermicelli cotti crudi con li pomodoro) was to make the tomato sauce dense, to cook the pasta just until firm, and to toss everything together in a pan. As for the accompanying tomato sauce, Cavalcanti wrote that whether it was made from fresh, dried, or preserved tomatoes, there was no point in describing its preparation, since everyone knew how to make it.

This recipe indicates that Cavalcanti was referring to an already established use, and not just in Naples. In fact, in the 1830s, the market for dried tomatoes was strong in Cagliari “because the sauce made from them [is] very good with maccheroni, which the middle and lower classes like so much.” Likewise, Cagliari was then a renowned center for the manufacture of pasta. A recipe for “macaroni à la napolitana,” combining pasta and tomatoes, first appeared in an American cookbook just a few years later, in 1847. By the 1880s, the tomato had been established as the condiment of choice for pasta for the peasants of the Campania region, and pasta itself had become a staple, as the findings of the Jacini Parliamentary Inquiry make clear. Even prisoners ate it, at least on religious holidays. On these occasions, prisoners in the southern Italian province of Capitanata were given maccheroni al ragù, the sauce made with tomato conserva and beef.

In Naples, the word for “tomato,” pommarola (or pummarola), also referred, by extension, to a simple tomato sauce. In this guise, it even entered Tuscan regional cuisine, as pomarola. Although the Tuscans frequently used tomatoes, the sauce was evidently an import and is now regarded as a mainstay of “traditional” Tuscan cookery. A similar linguistic transfer took place in Sardinia. In Cagliari, tomato sauce became so common as a condiment while the island was under Piedmontese rule that it was simply referred to as bagna, the Piedmontese word for “condiment” or “sauce.”

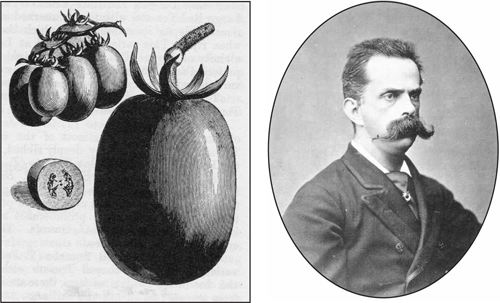

Not only was there a new use for the tomato, as a sauce for pasta, but by this time there also was a variety of tomato particularly suited to it. Dating from the first half of the nineteenth century, this small, egg-shaped variety was called the ‘Fiaschetto’ (also ‘Fiaschella’), from the word for “small flask” or “powder horn.” Italy’s seed industry was in its infancy, in contrast to that in Britain, France, and the United States. But the ‘Fiaschetto’ tomato was one of three available as seed from the experimental farm in Naples in 1861. Twenty years later, several different varieties of related egg-shaped tomatoes were being grown in southern Italy, particularly around Naples. Most were made into conserves, according to Les Plantes potagères, by Vilmorin-Andrieux, France’s premier nursery. The 1885, English edition of the book makes the first reference to a variety named in honor of Italy’s King Umberto, when he made his first visit to Naples in 1878. The ‘Re Umberto’, or ‘King Humbert’, tomato was “distinguished by its rather peculiar form and appearance” (figure 20). Was the king pleased to be associated with this variety? The fruit had an oval shape but was flattened on the sides, “about the size of a small hen’s egg,” “of a very bright scarlet color”; grew “in clusters of from five to ten”; and was a most “extraordinary cropper.”

The productivity of the ‘Re Umberto’ (and other egg-shaped varieties) made it attractive to growers around Naples. In addition, since it was a trailing variety, it was cheaper to cultivate, as it did not require staking. The city’s high demand for tomatoes thus could be met. Naples also shipped out huge quantities of other fruits and vegetables. By the early 1890s, more than 30 tons of vegetables left Naples every day by rail, for the markets of Rome, Florence, Milan, and Turin. Most tomatoes, though, were still consumed nearby. The squat, bushy ‘Re Umberto’ plants, with their numerous small, bright fruits, helped decorate country areas, making them “appear to be … more gardens than fields,” according to a report by the Ministry of Agriculture.

Figure 20 The ‘Re Umberto’ (‘King Humbert’) tomato (left) and its namesake (right).

One of the small ironies of history is that this most important variety of tomato was almost lost and is now a rarity eagerly sought by Italian collectors of “heirloom” seeds.

For King Umberto, it was a tomato, but for his wife, Queen Margherita, it was a pizza. This was appropriate, since the tomatoes that first adorned the pizza Margherita was the ‘Re Umberto’. The story is that the queen was tired of the French cuisine at court, so while she was visiting Naples in 1889, she brought a famous pizzaiolo, Raffaele Esposito, to the palace in Naples, at Capodimonte. Esposito prepared three pizzas for her in the palace’s pizza oven, which had been built for the Bourbon king Ferdinand II. One of the three pizzas was seasoned with tomato, mozzarella, and basil—the red, white, and green echoing the colors of the flag of the newly unified Italy.

Whether the pizza was invented for Queen Margherita or whether Esposito simply used an old recipe is unclear, but the latter is more likely. In any case, what is important is that a new culinary tradition was “invented” in the process. Many European culinary traditions, and the dishes they encompass, go back no further than this period, despite the patina of antiquity and timelessness subsequently attached to them, and the pizza Margherita is no exception.

As an “invented tradition,” the pizza Margherita combined several elements: the populism of the new Savoyard monarchy at the expense of the vanquished Bourbons; the triumph of local, popular cooking over the imported French cuisine; and the Italianizing of a Neapolitan dish in the shadow of the Risorgimento, the movement to unify Italy. Today, in an age of greater regionalism, this tradition is harder to accept. Advocates of “southern pride” would like to see it renamed the pizza Ferdinando, in honor of the Neapolitan kings—father and son—who first developed a taste for pizza.

As is the case with pasta, the history of pizza began long before the arrival of the tomato. Pizza is a simple food, meant to be consumed on the move. In its soft form, it is reminiscent of the nan of India; in its hard form, it resembles the Berber bread of Algeria. In Italy, leavened or not, pizza had various names. By the nineteenth century, pizza had become an urban, plebeian food. The first references to pizza ovens, similar to bread ovens, where pizzas are publicly made and sold come from late-seventeenth-century Naples. ’Ntuono, where the Bourbon king Ferdinand II visited incognito, was already in operation by 1732. (It moved to the Port’Alba area of the city in 1738, and something like it is still there, although as a restaurant.) By the middle of the century, Naples had more than eighty pizzerie. Twenty of them had small tables outside for the convenience of their clientele. The pizzerie also supplied the peddlers who sold pizzas in the city’s streets, carrying them on their heads in round metal containers to keep them warm.

The role of pizza in the life of the Neapolitan poor was described by Alexandre Dumas, who lived in Naples in 1835. In Le Corricolo, the author of The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo (and much else) brought his Romantic novelist’s eye to the city. Although Dumas may not be entirely reliable on points of fact, he did have a keen eye, and in matters of food, he considered himself an expert. Indeed, later in his life, Dumas wrote a six-volume dictionary of food, which is still in print.

Dumas says of pizza that although at first glance it appears to be a simple food, on closer examination it is actually quite complex. For six months of the year, pizza was the staple in the diet of the city’s poor, as it was cheaper than pasta, which was reserved for Sundays. The price of pizza was determined by various factors, Dumas observed. First was its diameter. A two-centesimi size would feed a man, and a two-soldi size pizza would feed an entire family. The price also depended on the strength of the market, so it varied according to the freshness and price of the ingredients used, such as oil, lard, pork fat, cheese, tomatoes, or small fish. Pizza even could be purchased on credit and paid for later.

None of this impressed Carlo Collodi. In an anthology for Italian schools, Il viaggio per l’Italia di Giannettino (1882–1886), written just twenty-five years after Italy’s unification, Collodi described pizza for his young readers:

Do you want to know what pizza is? It is a flat bread of leavened dough, toasted in the oven, with a sauce of a little bit of everything on it. The black of the toasted bread, the off-white of the garlic and anchovies, the greeny yellow of the oil and the lightly fried greens, and the red bits of the tomatoes scattered here and there give the pizza an air of messy grime very much in keeping with that of the man selling it.

Beyond their use in pasta and pizza, tomatoes were fast becoming an indispensable element in the southern Italian diet. The nuns of Santi Giuseppe e Anna in Monopoli (Bari Province) purchased tomatoes on sixty-three occasions in 1846—that is, nearly every day during the growing season—but the use of tomatoes was evident as well in other regions of Italy around this same time. Tomatoes and tomato purée took the place of pork fat as a condiment for staples like bread, polenta, and rice. Their increased consumption went hand in hand with their increased cultivation.

The place of tomatoes in rural Tuscany is well illustrated by Collodi’s famous children’s book, The Adventures of Pinocchio, first published in book form in 1883. One of its important themes is the juxtaposition of hunger and gluttony. Collodi creates a tension between money and eating, on the one hand, and poverty and hunger, on the other, which was not only the potentially tragic reality of Pinocchio’s world but also the reality of Italian society at that time. In chapter 13, the Fox and the Cat are about to trick the wooden puppet Pinocchio into giving them five gold pieces, which Pinocchio was supposed to take back for his father, Geppetto:

They walked, and walked, and walked, until at last, toward evening, they arrived dead tired at the inn of the Red Crawfish… . Having gone into the inn they all three sat down to table: but none of them had any appetite. The Cat, who was suffering from indigestion and feeling seriously indisposed, could only eat thirty-five mullet with tomato sauce, and four portions of tripe with Parmesan cheese; and because she thought the tripe was not seasoned enough, she asked three times for the butter and grated cheese… . The one who ate least was Pinocchio. He asked for some walnuts and a hunch of bread and left everything on his plate.

Some time later, Pinocchio jumps into the sea, only to find himself in a fisherman’s net. Pinocchio explains to the fisherman that he is not a fish to be eaten, but a puppet. The fisherman replies that he has never caught a “puppet fish” and asks how he would prefer to be cooked: “Would you like to be fried in the frying pan, or would you prefer to be stewed with tomato sauce?”

In Tuscany, the tenant farmers (mezzadri) used tomatoes sparingly in soups or with stale bread in their pappa col pomodoro. Essentially a bread-and-tomato soup, pappa col pomodoro became known throughout Italy thanks to a children’s story first serialized in 1907/1908, Vamba’s Il giornalino di Gian Burrasca (which has never appeared in English). “Long live pappa al pomodoro! ” becomes “Johnny Hurricane” ’s motto as he rebels against the dull diet of rice soup at the boarding school where his parents have sent him in an attempt to teach him how to behave.

Bread was still a basic foodstuff in Italy, an essential element of the daily diet. More often than not it was consumed stale, since in rural areas bread was baked in communal ovens only every week or two. Another humble dish of the Tuscan region was panzanella, in which pieces of stale bread were moistened in water or vinegar and broken into crumbs. To this was added whatever seasonal vegetables the mezzadro could grow in his own kitchen garden: onions, carrots, cauliflower, greens, cucumbers, and, as an innovation, tomatoes. The innkeeper Bicchierai called panzanella “a poor man’s dish, but tasty and pleasing to gentlemen, priests and government officials, too.” It is a useful reminder to know that something created out of necessity and poverty might also be considered “good” at the time. Like the acqua-sale popular in parts of southern Italy, which it resembles, panzanella today is touted as a crucial part of the “Mediterranean diet.” Both are now inconceivable without tomatoes.

The peasants of Lazio added tomatoes to their thick vegetable soup, minestrone, or used it to make a “mock sauce” (sugo finto) for beans or lentils. Tomatoes even appeared farther north. In Le barufe in famegia (1872), the Venetian playwright Giacinto Gallina has his lower-middle-class family arguing over whether to have rice with tomatoes for supper. In Udine (Friuli), a recipe for tomato sauce was included in a handwritten collection of 182 recipes compiled in the early nineteenth century by the noble Caiselli family. A similar collection compiled by Lucia Prinetti Adamoli in Varese (Lombardy) and dating from the mid-nineteenth century contains a recipe for “tomatoes à la provençal.” She copied the recipe from Giovanni Vialardi’s Trattato di cucina (1854), but it originated decades earlier in Paris and also can be found as Vincenzo Corrado’s pomidori alla Napolitana. The recipe is for baked whole tomatoes stuffed with grated cheese, bread crumbs, and parsley and moistened with broth or sauce.*Italy’s Jews were eating stuffed tomatoes too, with rice and bread crumbs, according to an anonymous poem written for the celebration of Purim.

It is in the first explicitly “Italian” cookbook that we find the best examples of the spread of tomatoes, especially in the form of conserva. This was Pellegrino Artusi’s La scienza in cucina e l’arte di mangiar bene, first published in 1891. It was Artusi’s mission to create an Italian cuisine, thirty years after Italy’s unification. The recipes in the book are from Tuscany, Emilia Romagna, and other regions, as well as a mixture of high and low cuisines. Artusi gives two recipes for tomato conserva, one savory and one sweet. He stresses the great usefulness of the conserva, commenting that “if the tomato were rarer, it would cost at least as much as truffles.” For example, in Artusi’s recipe for tripe, a poor man’s dish, the tripe was to be cooked in butter to which a meat sauce would be added or, “if you do not have that, tomato sauce.”

In his cookbook, Artusi distinguished between sugo di pomodoro—tomatoes cooked and strained, with the possible addition of celery, parsley, or basil—and salsa di pomodoro. He told this story about the salsa:

There was once a priest from Romagna who stuck his nose into everything, and busy-bodied his way into families, trying to interfere in every domestic matter. Still, he was an honest fellow, and since more good than ill came of his zeal, people let him carry on in his usual style. But popular wit dubbed him Don Pomodoro (Father Tomato), since tomatoes are also ubiquitous. And therefore it is very helpful to know how to make a good tomato sauce.

This is followed by brief recipe for tomato sauce.

Pellegrino Artusi’s Tomato Sauce (Salsa di pomodoro)

Prepare a battuto with a quarter of an onion, a clove of garlic, a finger-length stalk of celery, a few basil leaves and a sufficient amount of parsley. Season with a little olive oil, salt and pepper. Mash 7 or 8 tomatoes and put everything on the fire, stirring occasionally. Once you see the sauce thickening to the consistency of a runny cream, pass it through a sieve and it is ready to use.

This sauce lends itself to innumerable uses… . It is good with boiled meat, and excellent when served with cheese and butter on pasta, as well as when used to make the risotto described in recipe 77 [risotto coi pomodori].

Pellegrino Artusi, Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well, trans. Murtha Baca and Stephen Sartarelli (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003), 121.

Artusi also provides two recipes for “Neapolitan-style macaroni” (maccheroni alla napolitana), and the second is now a mainstay of Italian cuisine: classic comfort food. Artusi’s first recipe is for a gently simmered, meat-based sauce for pasta using tomato passata, with the meat from the sauce served on the side. The meat should be a mixture of beef and pork, a “hodgepodge of spices and flavors,” which Artusi finds pleasing. He claims to have obtained this recipe from a family in Santa Maria Capua Vetere, just north of Naples. Along with millions of Italians, Neapolitan-style macaroni, or something much like it, traveled across the Atlantic, to become a classic of Italian American cooking.

*The Adamolis liked the recipe enough to grow tomatoes on their estate in 1864. Because their son Giulio had taken part in Garibaldi’s invasion of Sicily, as one of “the Thousand,” it is possible that he learned to like tomatoes there and brought some seeds home with him, thus helping unite the new country in a culinary way, too.