A survey on the condition of farming in Tuscany, conducted in 1759 by the physcian-botanist Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti, included tomatoes among the “fruits prized by men as foodstuffs or as condiments for them.” By this time, the tomato was not just an agricultural and culinary presence but also an artistic presence. Carlo Magini was the first Italian painter since the very early seventeenth century to put tomatoes in a still-life painting, and he did it on numerous occasions. A native of Fano in the Marche, Magini was active in the second half of the eighteenth century, making a modest living by painting portraits, devotional works, and still lifes. His still lifes are simple kitchen scenes, painted in the neoclassical realism of the time and offering the viewer an intimate contemplation of everyday objects that may have reflected the painter’s own social status, which was far from well off. Magini represented objects like the clay pots typical of the region, a brass lantern, a bottle of local wine, a loaf of bread, eggs in a pan, cheese on a plate, cured meats, vegetables, and fruit, all usually arranged on a small table or buffet. Each painting was a meal or a dish waiting to be cooked and consumed. Furthermore, Magini’s depictions closely fit actual dietary practices. Thus a real-life lunch eaten at the Jesuit teaching college in nearby Loreto on a Friday in January 1720 consisted of “soup of black-eyed beans, portion of eel, pan-fried egg, apple, and cheese.”

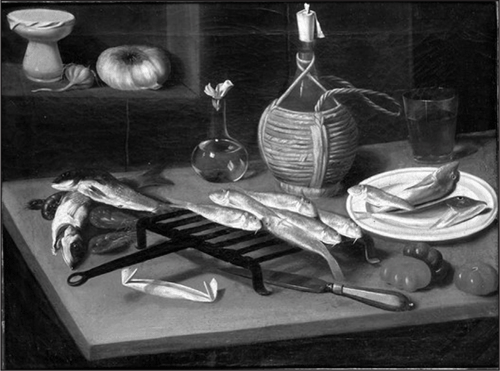

Figure 12 Carlo Magini, Still Life with Mullet, Grill, Wine Flask, and Glass (second half of eighteenth century; oil on canvas). This is one of the few still-life paintings in which Magini depicted fish, which is strange given that he spent almost all his life in the coastal town of Fano. (Courtesy of the Pinacoteca Comunale di Faenza)

Of the no fewer than ninety-nine still lifes attributed to Magini, six contain tomatoes. They are furrowed and misshapen, in groups of two or three, red and green, and usually in one of the bottom corners. Whether tomatoes were eaten green or were included for chromatic contrast is hard to say. Four of Magini’s still-life paintings do, however, suggest how the tomato might have been prepared and eaten: combined with eggplants and squash, to be served with cheese; or as a condiment with eggs and cardoons (gobbo), chicken (with celery and onion), or grilled mullet (figure 12). An intriguing possibility is that tomatoes were being eaten in salads, since Magini once places one alongside lettuce and cucumbers. Besides Magini, a contemporary of his, Nicola Levoli, who was active just slightly to the north in Rimini, had a similar background and painted similar scenes. Levoli’s Still Life with Fish on the Grill (1770–1800) contains three tomatoes, two red and one green.

What had happened since the early seventeenth century to alter attitudes toward the tomato? This chapter looks at how the acclimatization of the tomato slowly gave way to its acculturation during the eighteenth century and how the tomato’s “botanical” phase, examined in chapter 1, paved the way for its more widespread cultivation and consumption.

The changing attitude toward fruits and vegetables that characterized the late Renaissance period was partly responsible, as were the changing medical and scientific notions about how the process of digestion worked.

By the mid-seventeenth century, medical ideas had shifted away from the dominant Galenic ideology of previous centuries. Consequently, the system of the “humors” began to lose authority among physicians as well as dietary writers. Moreover, the new medical ideas meant that the tomato, as long as it was cooked, was no longer perceived as a health risk. This shift was characterized by two new medical theories, sometimes competing, sometimes complementary. The first of these was “chemical” medicine based on the ideas of Paracelsus and Jan Baptist van Helmont, which saw the body’s functions as chemical processes. The second was “mechanical” medicine, which regarded the body as a machine. According to this new mechanical model of digestion, the body’s input and output could be measured and quantified mathematically.

Previously, according to Galenic humoral notions, the tomato was thought to hinder digestion, owing to its acidity and its cold and damp nature, which, Galenic physicians thought, remained in the body and corrupted the humors. Now, however, the tomato’s characteristics were believed to help the process by breaking down foods. The mixture of salty and acidic foods seemed to aid in the “fermentation” of food in the stomach. Thus although the tomato itself had not changed, the attitudes toward it had.

Another, broader, point affected ideas about food and diet as well. Partly as a result of these new medical systems, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century physicians were less interested in discussing the relative merits and threats of different foodstuffs. Instead, medicine was increasingly directed to the definition and treatment of diseases, rather than the care of healthy bodies. Dietetics was accordingly separated from medicine and connected with other arts, like cooking. Eventually, by the early nineteenth century, a new field had taken the place left by dietetics: gastronomy, the study of “eating well.”

The tomato’s fortunes began to shift during the mid-seventeenth century. In 1640, the physician and botanist Pietro Castelli published Hortus messanensis, a description of the botanical garden in Messina, Sicily, in which the tomato appears under the heading “Medicinal Plants.” Castelli did not think of the tomato as a “garden plant,” which is how he classified the eggplant, nor did he list it with the nonmedicinal plants and flowers. But even though he regarded the tomato as a medicinal plant, Castelli must not have thought very much of it, as he did not even mention it in his detailed commentary on the medicinal ingredients found in Rome’s official pharmacopoeia.

From other sources, we know that the tomato was being eaten and not just grown. By the 1660s, the tomato appears in a list of the “many fruits [the Italians] eat, which we either have not, or eat not in England.” The list was compiled by the theologian, naturalist, and gardener John Ray during a three-year visit to the Continent from 1663 to 1666. In another, later work, Ray notes that in Italy tomatoes are cooked with marrows, pepper, salt, and oil. Although he had doubts about how healthy tomatoes were, Ray did believe that if they were cooked in oil, they might be good for scabies (then a widespread skin complaint). The tomatoes were not to be eaten, though, but rubbed on to the skin to take advantage of their perceived cooling and moistening effects. The remedy was not popular.

In Ray’s England, the tomato was a rarity. Still referred to as the “love apple,” it was obscure enough to be included in a “dictionary of difficult terms” published in 1677, and even then the dictionary’s author managed to get the definition wrong. He referred to it as “a Spanish root of a color near violet,” confusing it with both the eggplant and a root vegetable. Then, fifteen years later, the author of The Ladies Dictionary, Being a General Entertainment of the Fair-Sex (1694), repeated the errors, word for word.

Ray’s new Italian recipe for the tomato may have been inspired by Francisco Hernández’s Rerum medicarum Novae Hispaniae thesaurus, a description of the plants of New Spain, which finally was published in 1628 and again in 1658, as we saw in chapter 1. Hernández’s discussion of the native Mexican use of the tomato, with its combination of ingredients, was new to Italy. “One prepares a delicious dip sauce [intinctus],” Hernández writes, “from chopped tomatoes, mixed with chilies, which complements the flavor of almost all dishes and foods and wakens a dull appetite.”

The tomato owed its simpler, initial uses in Italy, as described in chapter 1, to the traditional concept of condiment. Condiments and seasonings served to balance a dish’s humoral “qualities.” By the seventeenth century, these combinations—think of serving prosciutto (salty, dry) with melon (watery, sweet), still a popular combination—were becoming routine. They were popular more for their pleasing gustatory contrasts than as humorally balanced dishes, however. Italian food writers were paying less and less attention to corrective rules in their combinations of foods and more attention to flavor. Personal experience and preferences, local practices and habits, were beginning to take precedence over ancient authority and received wisdom.

This newer association of tomatoes and squash, and sometimes with eggplants and chilies, entered Italy by way of Spain. This must have been a recognizable combination there by the time Bartolomé Murillo painted The Angels’ Kitchen (1646) for the Franciscan monastery of Seville. The right-hand side of the painting shows angels preparing a meal. In the corner, presented together as ingredients, are a red furrowed tomato, two eggplants, and a squash. Unfortunately, Spanish printed sources—plant books and cookbooks—do little to verify or contextualize this use. But we do know that the Sevillian Hospital de la Sangre made two purchases of tomatoes (and cucumbers) in July and August 1608.

The meal being prepared in The Angels’ Kitchen was essentially the recipe that the Italians, especially the Neapolitans, then ruled from Madrid, acquired from the Spanish. At least, this is how Antonio Latini acquired it. According to his autobiography, La vita di uno scalco, after an unfortunate start as a poor orphan, first in his native Fabriano (Marche) and later on the streets of Rome, in 1658 Latini was taken into the kitchen service of Cardinal Antonio Barberini, one of Pope Urban VIII’s numerous nephews. There, Latini quickly rose through the ranks to become kitchen steward (scalco). Over the next few years, Latini served as a steward in other noble and ecclesiastical households in Macerata, Bologna, and again in Rome, before being offered the post of steward to Esteban Carrillo y Salcedo, a grandee of Spain and regent to the Spanish viceroy of Naples. This was powerful, wealthy Spain, with an empire bridging the Old and New Worlds, so it was a great success for the forty-year-old Latini. Upon his arrival, Latini was given forty gold scudi to defray his travel costs and his new clothes “in the Spanish style” (figure 13). He was now in charge of cooking in Carillo’s villa on the slopes of Vesuvius, overlooking the Bay of Naples, where Carillo “often banqueted with the most noble personages in royal splendor and magnificence.” Here Latini was rewarded with the titles of knight of the golden spur and count palatine, dictated his autobiography in 1690, and compiled his masterpiece, Lo scalco alla moderna, published in two volumes a few years before his death in 1696.

Latini’s cooking is at once refined and eclectic, borrowing from his own broad range of experiences and contacts. On the one hand, it is the culmination of Italian court cooking before the triumph of French cuisine in the eighteenth century. On the other hand, Latini is not afraid to use popular food traditions, from vegetable soups to tripe and other offal; to develop a “new way of cooking without spices,” using herbs rather than strong flavorings; and to experiment with newer ingredients, like turkey, chocolate, chilies, maize, and, of course, the tomato. All the dishes in which the tomato appears are indicated as “in the Spanish style” (alla spagnuola). The first is a fiery tomato condiment to accompany boiled foods. The second brings together eggplants, squash, tomatoes, and onions, a combination that became a Mediterranean standby, apparent in the Catalonian samfaína and the Provençal ratatouille. The third tomato recipe takes the form of a hearty mixed meat stew, named after the pot, cassuola, in which it was cooked. Latini named this dish cassuola alla spagnola when he served it as one of fourteen hot first-course dishes at a wedding banquet in April. How he got tomatoes in April, Latini does not say. (This was almost three centuries before the Dutch mastered year-round hot-house production.)

Figure 13 Antonio Latini posing in all his Spanish finery. (From Latini, Lo scalco alla moderna [Naples: Domenico Antonio Parrino e Michele Mutii, 1692, 1694])

Latini’s three recipes are the first time tomatoes were used in European culinary literature. They met the increasing demand for condiments and dishes that were flavorful but not based on spices. Cooks now were trying to stimulate the appetite with delicate and pleasing foods. If they became more digestible in the process, so much the better; but it was not their main aim any more.

Antonio Latini’s Tomato Recipes

Salsa di pomodoro alla spagnola (tomato sauce, Spanish style). Take half a dozen ripe tomatoes and roast them in embers, and when they are charred, carefully remove the skin, and mince them finely with a knife. Add as many onions, finely minced, as desired; chilies [peparolo, in Neapolitan dialect], also finely minced; and a small amount of thyme. After mixing everything together, add a little salt, oil, and vinegar as needed. It is a very tasty sauce, for boiled dishes or anything else.

Minestra alla molignane (eggplant dish). Cut [the eggplants] into small pieces; add minced onions and squash [cocuzze], likewise cut small; and diced tomatoes. Lightly sauté everything together with aromatic herbs, with sour grapes if they are in season, and with the usual spices. You will produce a very good dish, Spanish style.

Cassuola di pomadoro (tomato casserole). Fill the pot [cassuola] with pieces of pigeon, veal breast, and stuffed chicken necks. Stew well in some good broth, with suitable aromatic herbs and spices, together with cockscombs and testicles. When the stew is cooked through, roast some tomatoes in embers, peel them, cut them into four pieces, and add them to the soup along with the rest of the ingredients, making sure not to overcook them, as they require little cooking. Then add some fresh eggs and a little lemon juice, and allow the mixture to thicken, covering it with a lid and applying heat both above and below.

Antonio Latini, Lo scalco alla moderna (Naples: Domenico Antonio Parrino e Michele Mutii, 1692, 1694), 1:444, 2:55, 1:390.

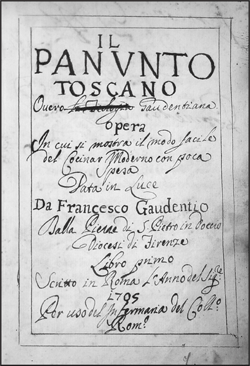

A recipe collection dating from 1705 suggests how the tomato’s use was spreading (figure 14). The manuscript’s author, Francesco Gaudentio, was born in Florence in 1648 and became a lay assistant with the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). He worked first at their colleges in Spoleto and Arezzo before joining the Collegio Romano, the Jesuits’ flagship educational institution in Rome, where he was a porter and cook at the college’s infirmary until his death in 1733.

Figure 14 The title page of Francesco Gaudentio’s manuscript recipe collection “Il Panunto toscano, overo la teologia gaudentiana … ” (1705). Gaudentio was evidently inspired by fellow Florentine Domenico Romoli, nicknamed “Il Panonto” (after a simple specialty of seasoned, toasted bread), the author of a culinary manual first published in 1560. (Courtesy of the Biblioteca Città di Arezzo)

Because the Collegio Romano was residential, food was important. Moreover, as the Catholic world’s foremost missionary and teaching order, the Jesuits took food and diet seriously. Each of their institutions kept extensive records of what food was served each day. These records were known as a Levitico, from the Levitical laws and rituals, because they detailed the different foods consumed on fast and feast days, according to the Catholic Church’s calendar. The Levitico for the Roman Province of the Society of Jesus suggests a balanced regime of vegetables, legumes, and fruit; meat and fish; and pasta, bread, and rice, accompanied by cheese and eggs. Supplementary foods were offered to those taking medicines and to visiting guests and dignitaries. This regime is filling and nutritious but not extravagant, although, of course, most Italians then could only dream of such a diet. Indeed, roughly one-third of the Collegio Romano’s expenses in the late seventeenth century were for food.

Francisco Gaudentio’s Tomato Recipe

How to cook tomatoes. These fruits are something like apples, as they are cultivated in gardens and are cooked in the following way: Take the tomatoes, cut them into pieces, and place them in a pan with oil, pepper, salt, minced garlic, and mint. Sauté the tomatoes, turning them frequently, and if you wish, add some tender eggplants or squash and they will improve it.

Francesco Gaudentio, “Il Panunto toscano, overo la teologia gaudentiana … ” (1705), MS 450, fols. 366–67, Biblioteca Città di Arezzo.

Gaudentio’s recipes are simple, practical, and unpretentious. An entire section is devoted to cooking for the sick Jesuit priests, novices, and students, but he also notes that all the recipes in the collection can be made for the sick by adjusting the seasonings and ingredients in accordance with a physician’s advice. His recipe for tomatoes is one of several dealing with sauces and condiments.

Gaudentio’s inclusion of tomatoes in his collection suggests that he did not consider them unhealthy. Moreover, he refers to tomatoes being “cultivated in gardens,” pointing to their increasing availability. It is easy, in fact, to imagine the occasional tomato plant finding space in the market gardens and plantations of specialized plants and shrubs that extended around Italian towns, the “Mediterranean garden” described by Emilio Sereni. The tomato’s transition to the open field alongside the staple crops was still in the future, however.

The tomato’s reputation was changing, although it is difficult to pinpoint the time of this change and find details of how tomatoes were being eaten. Other than Gaudentio’s own unpublished work, no Italian cookbooks were published between 1694 and 1773. The only cookbooks to appear were translations of French works, testimony to the popularity of French cuisine at this time. In France, tomatoes were just beginning to make the journey north from Provence. In 1772, the Vilmorin-Andrieux seed catalog lists the tomato as a “vegetable” for the first time, whereas previously it was considered an ornamental. In the following year in Italy, the chef Vincenzo Corrado, although still careful to remove the tomato’s harmful skin and seeds before cooking it, acknowledged that tomatoes were “to be enjoyed” (figure 15). Corrado accordingly included tomatoes in many of the recipes in his cookbook Il cuoco galante, opera meccanica (1773), all meant to accompany meat, fish, and eggs. Corrado was a Celestine Benedictine monk in Naples, and as a young man he had traveled throughout Italy from 1758 to 1760, visiting the Benedictine order’s houses. His cookbooks illustrate how the cultivation and consumption of the tomato was spreading throughout Italy in the mid-eighteenth century.

Figure 15 Forty-year-old Vincenzo Corrado, dressed for work. (From Corrado, Del cibo pitagorico ovvero erbaceo [Naples, 1781])

In 1784, in Del cibo pitagorico ovvero erbaceo, his book on cooking vegetables, Corrado wrote that tomatoes were not only tasty but good for us, too. “According to the physicians,” Corrado wrote, “their acidic juice aids digestion considerably, especially in their own summer season, when man’s stomach is loosened and nauseous because of the great heat.” Some doubts about tomatoes may have remained, however, for a 1796 agricultural treatise felt obliged to reassure its readers that the Italian climate rendered tomatoes harmless. In addition, newer varieties were of a “delicate taste and less acidic.”

Corrado’s book usually is cited as the first time tomatoes enter the Italian diet, but in fact, he was building on an established culinary tradition. Other sources suggest that by at least the mid-eighteenth century, tomatoes already were widely used, albeit in limited ways and apparently by only the social elites. Tomatoes also were being used in ways quite different from how they were in Mexico, which was essentially how both Latini and Gaudentio had prepared them. For example, by the late 1750s the Jesuits of the Casa Professa in Rome were eating tomatoes routinely on Fridays, meatless of course, during the month of July, in the form of frittata con pomi d’oro. For them, tomatoes were a welcome addition to the usual Friday lunch omelet. On other days, tomatoes might be in a pasticciata, encased in pastry, to accompany boiled meat or veal. In sum, tomatoes were being adapted into Italian culture, blended with local ingredients and culinary techniques; that is, they were being acculturated.

Many religious institutions, like convents, produced food for their own consumption and for others outside the convent walls, so they often established new culinary habits. For example, the Celestine nuns of Trani were fond of brodetto al pomodoro (tomato soup); in fact, they ate it on twenty occasions in 1751. Later, in the 1770s and 1780s, the Benedictine nuns of the Sicilian city of Catania were eating tomatoes in daintier ways: either as an antipasto called a mortaretto, a light pastry filled with tomatoes and herbs, or as an accompaniment to eggs and anchovies as a terza cosa. This “third thing” was a varied course, either a savory or a sweet, served at supper after the soup and fish courses. This Benedictine convent was rich and had the most varied and elaborate diet of all the city’s religious orders, exhibiting the French influence characteristic of Sicilian aristocratic cooking of that time. Some two centuries earlier, the Italians supposedly had taught the French how to prepare food, so now the French were returning the favor, along with the notion that for those who could afford it, the enjoyment of fine food was less a capital sin than a sign of good taste.

The tomato’s increasing use in Italy made an impression on foreign visitors, one of whom was Peter Collinson, a London merchant, botanist, and fellow of the Royal Society. In 1742, he wrote the following in a letter to John Custis of Williamsburg, Virginia:

Apples of Love are very much used in Italy to putt when ripe into their brooths and soups giving it a pretty tart taste. A lady just come from Leghorn [Livorno, Tuscany’s main port] says she thinks it gives an agreeable tartness and relish to them and she likes it much. They call it tamiata. I never yet tried the experiment but I think to do it. They putt in but one or two at a time, the boiling breaks them and then they are diffused through the whole.

This culinary use of the tomato reminds us of Latini’s recipe of fifty years earlier, but here it was novel, so much so that tasting it was an “experiment” to Anglo-Saxons on both sides of the Atlantic. Even so, in the now proliferating gardening and horticultural literature of Britain and America, tomatoes still were listed under ornamentals and flowers, not under kitchen gardens.

Tomatoes now came in different varieties, from the red and yellow cherry type “used in medicine” to the larger, red variety with “furrowed sides,” used by the Spanish, Italians, and Portuguese in soups, sauces, and salads, “to which they give and agreeable acid flavor.” The words are those of Philip Miller, gardener to the London apothecaries’ guild and “member of the botanic academy at Florence,” in his book The Gardener’s Dictionary (1768). The large, furrowed tomato was the original variety obtained by early botanists and was still the most common in Italy and the one represented in Italian still-life paintings of the mid-eighteenth century. The tomatillo is no longer mentioned.

The Sardinians, at all social levels, may have been the first to take the tomato seriously, perhaps because the island was a Spanish possession until 1720. The Sardinians called them tumatas, close to the Spanish tomate. An anonymous Piedmontese writer encountered the tomato for the first time while visiting Sardinia in the 1750s. The island was now a Piedmontese possession, ruled from Turin. In Descrizione dell’isola di Sardegna, he wrote that “this fruit is of a dark red, its shape is round like an apple, its taste sour; the Sardinians cook it with meat and eat it as a soup,” and “the Piedmontese cooks [resident on the island] make exquisite sauces from it.”

Curiously, a Sardinian was credited with being the first person to eat tomatoes, mixing tomato juice with beef gravy, in the “Old Northwest” of the United States (what became Illinois and Indiana). His name was Francis Vigo, and he had served in the Spanish army before establishing himself as a merchant in the 1780s. Vigo may have encountered the tomato anywhere in his travels from Sardinia through Cuba and Louisiana, all places where it was consumed.

A more reliable guide to the preparation of the tomato in Sardinia is an anonymous agricultural treatise from the mid-eighteenth century, which contains two Sardinian tomato recipes, both ways to preserve them. These recipes are a milestone in the tomato’s history in Italy, as the ease with which tomatoes can be preserved and the various ways of doing it were crucial to their “success.” The first recipe, “in the Spanish style,” mixed sour grapes, chilies, and “less than ripe tomatoes” and covered them in vinegar. The result was a condiment to be added to sauces and stews throughout the year. The tartness of the condiment recalls the earliest Italian tomato recipes.

The second Sardinian recipe uses sun-dried tomatoes, which is perhaps the earliest reference to drying as a means of preservation. Because tomatoes were available fresh only from July to October, it was necessary to find ways to preserve them for kitchen use throughout the rest of the year. Foods had been dried as a means of preservation since ancient Greece. Using that method, the anonymous agricultural treatise advised, “Gather the ripe and round whole tomatoes before it rains, cut them down the middle and, so sliced … put a little bit of salt on each half, and [when they are] dried, bottle them, to be used throughout the year.” By 1780, the salted, sun-dried tomatoes were being ground for use later as a seasoning. From the early nineteenth century, the method of sun-drying tomatoes is recorded also in the Neapolitan province of Principato Citeriore, as well as sun-drying eggplants, chilies, and whole melon skins, the last to be used as salt containers.

By the 1830s, but probably earlier too, enterprising peasant women in the Cagliari area were selling sun-dried tomatoes. This is an important reminder of the role of gender in agrarian change. Indeed, women frequently were responsible for the cultivation, preparation, and sale of foodstuffs, and tomatoes were becoming an important element of domestic production, if not consumption. After all, they were being sold, not necessarily eaten, in order to bring in extra income as part of the varied economic activity of the rural household. The implements required for sun-drying already were in the rural kitchen, such as the drying racks made of canes tied together and the clay cooking pots.

Another, equally common, way to preserve tomatoes for use throughout the year was reducing them into a thick paste. Before Nicolas Appert and the advent of bottled preserves, these pastes necessarily had to be quite dry. In the words of the agronomist Filippo Re, “Not only is the tomato used when it is fresh, but a conserva is obtained from its juice, which is thickened over the fire, then reduced to a solid consistency, and much used on choice dishes [manicaretti] throughout the year.” This paste came to be known as a conserva nera (black or dark preserve). If this is hard to imagine, an American cookbook from 1847 provides a few details (although the addition of other vegetables and spices is new). A dense preserve like that in the cookbook was used as a seasoning for soups and meats and in sauces. It appears in the kitchen account books of the Saluzzo family, dukes of Corigliano (Calabria), for the years 1789 to 1791, as salsa or conserva di pomodoro. It is listed alongside other spices and flavorings like cinnamon, nutmeg, and black pepper, which is an indication of how it was perceived.

Italian Tomato Paste

Take a peck [9.6 quarts] of tomatoes; break them and put them to boil with celery, four carrots, two onions, three table-spoonfuls of salt, six whole peppers, six cloves, and a stick of cinnamon; let them boil together (stirring all the time) until well done, and in a fit state to pass through a sieve; then boil the pulp until it becomes thick, skimming all the time. Then spread the jelly upon large plates or dishes, about half an inch thick; let it dry in the sun or oven. When quite dry, detach it from the dishes or plates, place it upon sheets of paper, and roll them up. In using the paste, dissolve it first in a little water or broth. Three inches square of paste is enough to flavor two quarts of soup. Care should be taken to keep the rolls of paste where they will be preserved as much as possible from moisture.

Sarah Rutledge, The Carolina Housewife (Charleston, S.C.: Babcock, 1847), 105, reprinted in Andrew Smith, The Tomato in America: Early History, Culture, and Cookery (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001), 177.

Corrado, the Benedictine monk and cookbook author, helps fill in the details of these references to the use of tomatoes. For example, his recipe for salsa di pomodoro uses fresh tomatoes, not dried, which then are cooked. When the salsa is to be served over mutton, mutton gravy is added, and when the salsa di pomodoro is to accompany scorpion fish, it is prepared with butter, garlic, and bay leaf. These two suggested uses correspond to what Corrado elsewhere calls his two versions of tomato condiment: with and without meat. The latter version is intended for the many meatless or “lean” days of the Catholic calendar. In addition, Corrado recommends his colì di pomodoro—from the French coulis, referring to a condensed sauce—as an accompaniment to a wide variety of foods: veal, sliced veal head, stuffed small chicken, turtledove, roast sturgeon, trout, sliced crayfish, poached eggs, and squash.

A Selection of Vincenzo Corrado’s Tomato Recipes

Pomidori alla Napolitana (tomatoes, Neapolitan style). After cleaning the tomatoes of their skins and cutting them in half, you will remove their seeds and place them on a sheet of paper greased with oil in a baking tray. You will fill the tomato halves with anchovies, parsley, oregano, and garlic, all finely chopped and seasoned with salt and pepper. Having covered the tomatoes with bread crumbs, you will bake them in the oven, and serve them.

Zuppa alli pomodoro (tomato soup). Cook a quantity of tomatoes in a beef broth with a small bunch of aromatic herbs. After clarifying this broth, add toasted bread crusts, and serve with a tomato coli seasoned with basil, thyme, and parsley, on top.

Salsa di pomodoro (tomato sauce). After cleaning the tomatoes of their skins and seeds, you will chop them together with garlic cloves, red chilies, pennyroyal, and rue. After straining this mixture with the addition of oil and seasoning it with spices, boil it with vinegar and mutton sauce, and serve it warm over mutton.

Vincenzo Corrado, Il cuoco galante, opera meccanica (1773; Naples: Raimondi, 1786; facsimile ed., Sala Bolognese: Arnaldo Forni, 1990), 140, 158, 189.

It is interesting that in many respects, Corrado’s recipe for zucche lunghe alla parmegiana—he did not approve of eggplants—otherwise resembles the modern one for “eggplant Parmesan.” The squash is cut in round slices, salted to remove the liquid, fried (in pork fat, not olive oil), layered between butter and Parmesan cheese, and covered in a sauce made of eggs and butter before being baked. Later, tomato sauce found its way into the dish, and the squash was replaced by eggplant.

Corrado also profited from the new popularity of vegetables with his cookbook Del cibo pitagorico ovvero erbaceo (1781). As a seasoning for other vegetables, he recommends his purè di pomodoro. This is prepared by quartering the tomatoes; sautéing them in fat or oil with garlic, parsley, radish, bay leaf, and celery; and adding some broth and, when this boils, bread crusts, all of which is strained through a sieve. He describes this ancestor of the modern passata as a “tasty condiment, almost necessary to impart greater flavor to numerous vegetable dishes.” As this comment suggests, Corrado’s book was not meant as a guide to an austere and meatless Pythagorean diet in line with Antonio Cocchi’s recommendations, as discussed in chapter 2. Rather, it was intended to provide a way to make vegetables tastier. Corrado also suggests using tomatoes as a separate dish, as in his earlier recipe for pomidori alla Napolitana. For this, the tomatoes first had to be peeled, by placing them on embers or in boiling water, and then the seeds had to be removed. The tomatoes then were halved, stuffed with various fillings, and either baked or fried. He recommended round, yellow tomatoes (which he called saffron colored).

The tomato still had only a regional presence, limited to only a few areas. Nonetheless, in the tomato’s introduction to and early uses in Italy, the Spanish influence is clear. Most of the preceding references to tomatoes come from the south of the Italian peninsula, as well as the islands of Sardinia and Sicily, all formerly Spanish dominions. Tomatoes also could be found in Tuscany, where our story began, and cookbooks from Rome and Macerata suggest a presence in other parts of central Italy, like Lazio and the Marche.

The tomato’s use in northern Italy was more sporadic. Only in Liguria was it becoming an important agricultural product, part of the already thriving trade in fresh vegetables and fruit referred to in chapter 2. Household accounts show that in 1765 the Doria di Montaldeo, an aristocratic Genoese family, purchased tomatoes between July and September and then again in December (perhaps dried or as conserva). They were listed as tomate, suggesting either an abiding Spanish influence or a fashionable French one.

The French influence would seem to account for the introduction of the tomato in what was to become one of Italy’s main producing areas: the region around Parma. Jean-Gabriel Leblanc, chef to Napoleon’s second wife, Marie Louise of Habsburg-Lorraine, used pommes d’amour widely in sauces. When Marie Louise refused to follow her husband into exile in 1814, the Treaty of Fontainebleau made her the duchess of Parma, Piacenza, and Guastalla, and she brought Leblanc with her when she arrived in Parma two years later (becoming in time the much-loved Maria Luigia). The tomato came with them. Leblanc’s successor, Vincenzo Agnoletti, recommended, in a work published in 1832, using preserved tomatoes either dried in loaves (mattoncini) or as thickened sauce (passata), in soups or with fish and meat. Tomatoes were grown at the estate in Colorno, outside Parma, which supplied the palace with much of its produce. In August, a palace cook and two assistants would turn the tomatoes into paste. From the account books of Maria Luigia’s household, we know that in 1844, three years before her death, they made eighty jars of conserva, weighing 86 pounds.

By this time, tomatoes had spread beyond the Colorno estate and were being grown in the area’s rich farmlands.

As we enter the nineteenth century, we find more evidence of the tomato’s being eaten throughout society. In the words of a Tuscan botanist, Ottaviano Targioni Tozzetti, writing in 1813, tomatoes were “cultivated in all market and kitchen gardens,” and their use was “very common.” Luigi Bicchierai, called “Pennino,” ran an inn located at a crossing along the Arno River, at Ponte a Signa, not far from Florence. We do not know whether he was a typical innkeeper, for he had learned how to cook at a local monastery from two Neapolitan friars before taking over the family inn in 1812. Unlike most innkeepers, Bicchierai also found time to keep a commonplace book, a sometimes witty mixture of accounts, diary entries, recipes, and sonnets. Here he suggested using tomatoes in his poor-man’s meat sauce. In the best traditions of Tuscan frugality, the sauce uses leftover meat, along with potatoes, onions, herbs, and tomatoes. No one would be able to tell it from an authentic meat ragout, Bicchierai claimed.

Sugo della miseria (Poor Man’s Meat Sauce)

This sauce isn’t holy, but where it falls, it does miracles.

When you have made a nice selection of boiled meats, there is always some left over, and reheating it becomes a bit tiresome, likewise with meatballs.

So I undertook to create a sauce that would be pleasing. Thus, you take four good potatoes and cube them, chop an onion, three celery sticks, parsley, garlic, one leek, bay leaf, sage, cloves. Put everything in a pan to blend, with two glasses of white wine and a little broth.

Just before it is ready, add the sliced boiled or minced meat and the tomatoes, mix well, and use this in the same way as any other ragout; no one will realize it and will enjoy it all very much.

Luigi Bicchierai, Pennino l’oste, ed. Franco Tozzi (Signa: Masso delle Fate, 1996), 15.

Tomatoes had now become so common that people were throwing them away, or at least were throwing them. In Italy, tomatoes were the missile of choice to show disapproval of public performers, and the activity came to be known as a pomodorata. In July 1838, the Roman poet Giuseppe Belli composed a few poems for an upcoming recital at the city’s Accademia Tiberina. Unsure how the poems would be received, Belli wrote to a friend, “God save us from the tomatoes” (Dio ci salvi dai pomodoro).

For the peasants of southern Italy, tomatoes were all that they had to eat during the dog days of summer. In fact, vegetables formed the basis of the southern peasants’ diet, as we saw in chapter 2. The problem was that they “abounded” from late autumn through spring but, in the words of the Statistica murattiana of 1811, were “rare during the summer because of the lack of water.” At that time, only onions, garlic, chicory, chilies, eggplants, and tomatoes were available.

Growing tomatoes was, and still is, labor intensive. The soil had to be dug deeply, and the plants had to be well fertilized, watered, supported, and pruned as they grew (although in the south, the trailing varieties were later favored). Harvesting the fruit required the contribution of the whole family. But to compensate, the tomatoes matured quickly and produced abundant fruit. Along with chilies, tomatoes offered a bit of chromatic variety, which was welcome in a peasant diet monotonously colored a brownish green. Moreover, the color red had associations of wine and meat, both precious.

Tomatoes also were cheap. According to the Statistica, tomatoes sold for 3 grana a rotolo (a grano was a small copper coin, and a rotolo was equal to 2 pounds). For around 40grana a day, a family of five could subsist on the common mixture of bread, legumes, and vegetables, plus a glass or two of wine. At this time, vegetables might cost from 2 to 8grana per rotolo, so tomatoes were relatively inexpensive.

For all these reasons, almost everywhere in southern Italy, tomatoes formed part of the peasants’ “ordinary food,” part of the “subsistence of the population,” according to the Statistica. Tomatoes, as well as chilies and garlic, also were used as “both a food and a seasoning” by the peasants of Calabria Citeriore.

What sorts of tomatoes were cultivated? The Statistica tells us only that tomatoes were grown in many areas of southern Italy. For instance, they were cultivated in Terra di Lavoro, outside Naples, “with their varieties in shape.” An agricultural treatise published in the same year, Filippo Re’s L’ortolano dirozzato, fills in the details. The varieties were schiacciato (squashed or flattened), globoso (spherical), and peretto. The last is, in fact, the first mention of a new variety, the pear-shaped tomato, which was destined for great things later in the century.

In Basilicata, peasants took their tomatoes to market, to provide much-needed income. In Potenza, the sale of tomatoes and other vegetables by peasants from the surrounding countryside formed a retail trade. Peasants also supplied the towns of the district of Melfi, such was the “abundance” of produce. This trade was necessarily localized, given the poor means of transport, and the peasants around Naples stood to benefit the most. As a foretaste of things to come later in the century, in the Terra di Lavoro, tomatoes (along with chilies and cucumbers) were said to “offer great resources for the domestic economy of all families during the summer months.”

Tomato cultivation remained a cottage industry, outside the concerns of state governments. In the years when most of the Italian states were establishing small-scale “experimental farms” to encourage the production of cash crops, tomatoes are not mentioned at all. Instead, the farms focused their research and trials on plants of presumed economic importance, from grains and feed crops to plants used in the textile and dyeing industries. In the same way, local seed banks (monti frumentari), which provided peasant farmers with seeds for cultivation, concentrated on the staples, primarily wheat, but increasingly also legumes, potatoes, and maize.

The cultivation and consumption of tomatoes increased markedly during the nineteenth century. In Naples, this was paradoxically based on a decline in overall food consumption. There is evidence that the already poor diet of many southern Italians actually worsened after the unification of Italy in 1861. In Naples, now reduced to the status of a provincial capital, the per capita consumption of basic foodstuffs like meat and cereals fell markedly. Consequently, the urban poor compensated by eating still more fruits and vegetables. Producers were able to meet the rising demand by aiming for quantity over quality, thus cultivating cheaper, inferior varieties. The number of fruit and vegetable sellers in the city increased almost threefold between 1845 and 1881, at a time when the overall population rose only slightly. As a result, the diet of the poor was almost exclusively vegetarian.

This included tomatoes, even eaten raw! Culinary custom advised that tomatoes be cooked not once but twice. The first cooking was to remove the skin and seeds, and the second was to cook the tomatoes into a sauce or as a dish on their own. But two Neapolitan physicians, Achille Spatuzzi and Luigi Somma, writing about the health of the city’s vast proletariat, noted their “very great use” of tomatoes: “In the summer months, while [the tomatoes] are still unripe, they are eaten raw in a salad with onion, oregano, and so on.” This was part of a widespread diet of cheap unripe or rotten vegetables and fruits and resulted in the predominance of gastrointestinal complaints and indigestion during this time of the year. The doctors were right to be worried about the state of the city’s health. Thirty years earlier, Naples had suffered a severe epidemic of cholera, which had hit the poorest and most densely crowded areas the hardest.

The two doctors were not against tomatoes per se. On the contrary, “aside from the unripe tomatoes,” they judged them “valuable” and their use “praiseworthy,” especially as a condiment. But there was a clear class division. The city’s poor were eating tomatoes raw, either unripe or rotten, in salads, and setting aside the good tomatoes to be cooked in sauces or reduced into a paste for winter use.

Finally, and on a more positive note, the Neapolitan doctors offer us invaluable evidence of two local uses of tomatoes for which Italy would soon become world famous. They refer to the poor’s subsistence on something called pizza (and they italicized the word, for the particularly Neapolitan form they had in mind had not yet entered the Italian or any other language). They explained for the benefit of their readers that the pizza was “seasoned on the top with an abundance of oil or pork fat, with cheese, oregano, garlic, parsley, mint leaves, with tomato especially in summer, and finally sometimes even with small fresh fish.” Tomato was not a yet a basic element of pizza, but only one possibility among several.

For those who could afford it, tomatoes appeared in another new guise: “They form the customary seasoning for macaroni, and not a day goes by when they don’t appear on the tables of the middle class.” This is perhaps the earliest reference to pasta as a staple food, accompanied by a tomato sauce.