2

L1 sign language teacher preparation, qualifications, and development

Katharina Urbann, Thomas Kaul, Leonid Klinner, Alejandro Oviedo, and Reiner Griebel

Introduction

A quote that is attributed to Bonaventura Parents’ Organization in Denmark says: “if I accept another person’s language, I have accepted the person … if I refuse the language, I thereby refuse the person, because the language is a part of the self” (Pribanic, 2006: 233). Teachers in general would agree with the content of this quotation: It is every teacher’s duty to accept their learners and their identity. Learners’ identities are closely linked to language, and vice versa. For Deaf children, sign language should be offered as their first language (L1) as sign language remains the only barrier-free language that they can access.

One might be wondering why, for instance, hearing English native speakers in English-speaking countries attend compulsory English classes throughout their school years whereas Deaf children are not taught sign language. Why is something that may seem so obvious not taken for granted? Some exceptions can be found from an international perspective. Why there are exceptions, and how sign language teachers for children whose L1 is sign language are prepared and qualified, are discussed in this chapter by taking a look back, a look around, and a look ahead towards future trends.

The teacher preparation programs (TPP) for sign language teachers is diverse and heterogeneous. They differ within and across countries. In some countries, such as Belgium, there are no TPPs for L1 sign language teachers. Generally, the availability and content of TPPs depends on political frameworks, ideological constraints (e.g., oral vs. sign), and educational practice.

Looking back

From a historical point of view, one milestone is crucial when considering sign language to be an important factor in educating Deaf children. It is Stokoe’s (1960) analysis of American Sign Language (ASL), since it substantiated the linguistic status of sign languages. Stokoe’s work was a starting point of a scientific journey to investigate the richness and specificities of a visual-gestural language (Emmorey, 2002; Klima & Bellugi, 1979; Sandler & Lillo-Martin, 2006). Stokoe’s discovery led to a shift of perspective regarding sign languages and Deaf people in general. An era of broad scientific research analyzing Deaf people and their language began. Scholars from other scientific disciplines such as psychology, sociology, anthropology, and education began researching sign languages, Deaf culture, and Deaf people. This development led to an empowerment movement by Deaf people (Jankowski, 1997). Empowered by research, Deaf people postulated their right to use sign language and to naturally use sign language in the education of Deaf children.

As a result of these developments, it was suggested that sign language is and should be the native language (L1) of Deaf children. Bilingual bimodal education concepts were developed, examined, and approved in the 1980s in Scandinavian countries, Great Britain, and the US, and since the 1990s in Germany (Ahlgren, 1994; Günther & Schäfke, 2004; Günther & Hennies, 2011; Pickersgill & Gregory, 1998; Svartholm, 1993). The main goal was to provide an educational setting for Deaf children to acquire a sign language as their L1 within a natural language acquisition process. Currently, research in sign bilingual acquisition processes are rather devalued due to the early diagnosis of hearing losses and the availability of better technical hearing facilities, which enables Deaf children to acquire a spoken language (Dammeyer & Marschark, 2016; Knoors & Marschark, 2012; Swanwick, 2015). Yet, Deaf children’s prerequisites to acquire a sign language as an L1 differ widely.

Theoretical perspectives

L1 sign language teacher preparation should be based on considerations regarding sign language as L1, the population of d/Deaf children, and the TPPs in general.

Language considerations for sign language as L1

The acquisition of a sign language as L1 is a complex process. Deaf children grow up in an educational environment with a learner population that is characterized by diversity and heterogeneity. A Deaf child can be born to hearing parents or Deaf parents, or to parents from other countries using different spoken and/or sign languages. Deaf children’s language development varies depending on their parents’ hearing status and whether they use a spoken or sign language, and the quality and quantity of the parent‒children communicative interactions (Koester, 1995; Koester & Lahti-Harper, 2010; Spencer, 2003).

The Deaf children of Deaf parents who are fluent in sign language are able to acquire a sign language as their first natural language. The Deaf parents who communicate in sign language are able to provide an extensive and comprehensive language environment that enables their Deaf children to acquire a sign language as a L1. The children perform the same language milestones and developmental stages in sign language as hearing children in their spoken language development. Past studies have shown that the signing Deaf children of the signing Deaf parents have achieved an age-appropriate vocabulary and grammar development (Chen Pichler, 2012; Lillo-Martin, 2015; G. Morgan & Woll, 2002).

Demographics of deaf and hard of hearing children

In most places worldwide, 90–95% of Deaf children have hearing parents (Mitchell & Karchmer, 2004; Schein, 1987), who have no experiences in using sign language. Under these conditions the Deaf children of hearing parents do not grow up with the prerequisites for acquiring a sign language. Generally, they are not able to acquire sign language as an L1 through direct interaction and communication with Deaf sign language users. The children’s sign language proficiency differs depending on their opportunities to get in contact with competent sign language users and language role models. In most cases the acquisition process is significantly and noticeably delayed. The chance of acquiring a sign language as a L1 in a native fashion declines with age; the older the child is, the poorer the possibility (Cormier et al., 2012). Galvan (1999) revealed that delayed sign language acquisition negatively impacts the flexion system and the language’s complexity. Late learners seem to perceive signs more holistically compared to the analytic perception that captures phonemes and morphemes by native signers. The onset of language acquisition also has an impact on sentence processing in sign language, including the ability to analyze syntactic structures (Boudreault & Mayberry, 2006). Furthermore the sign vocabulary is limited and varies dramatically (Anderson, 2006; Lederberg & Spencer, 2001). Compared to native signers, early and late learners’ acquisition process noticeably differs in its depth and breadth, which also influences the learning process of other languages (Mayberry & Lock, 2003).

According to Newport (1988), the crucial factor for developing a language system is age of language acquisition, not the time of exposure to a sign language (Mayberry, 1993). As Deaf children of hearing parents lack high exposure to sign language in its depth and breadth, the language input is incomplete and reduced, which also impacts the Deaf children’s cognitive and social development (Figueras, Edwards, & Langdon, 2008; Hauser, Lukomski, & Hillmann, 2008; Hintermair, 2014; Morgan et al., 2014).

In this context the term “first language” (L1) is unclear. Four scenarios for sign language learners are defined in scholarly literature (Mayberry, 1993; Newport, 1988; Ortega, 2016):

1.Native Signers: Deaf children of Deaf adults, who undergo a typical sign language acquisition comparable to the acquisition of a spoken language by hearing children (Hänel-Faulhaber, 2012; Lederberg et al., 2013; Schick, 2011).

2.Early signers: Early signers are in most cases Deaf children of hearing parents, the latter of whom are often not competent sign language models for their Deaf children. The hearing parents might learn sign language after the diagnosis. Regarding the children, their first contact to sign language starts either in early education or at school by the age of 3 to 6 years, depending on the educational concept.

3.Late signers: Late signers are children, who are exposed to sign language after the age of six or even later. They may have received an oral or auditory verbal education or they are children of immigrants or refugees, who tend to have minimal opportunities to acquire a sign language. In some cases their language input is dramatically reduced. A late language acquisition has a negative impact on the linguistic development on all levels of linguistic structures.

4.Home Signers: If Deaf children have no access to a sign language environment and grow up among hearing people, their hearing family members may develop a basic idiosyncratic sign system (i.e., home signs) to manually communicate with their Deaf children on a very basic level.

When Deaf children enter classrooms where sign language is used, they get in contact with more than one language within a bilingual‒bimodal language acquisition. In doing so, they are exposed to a written and sign language. For Deaf children of hearing parents, this situation is challenging since both languages are not fully accessible. Furthermore, the language acquisition process of bilingually educated children differs from monolingual children growing up using one language (De Houwer, 2009; Plaza-Pust & Morales-López, 2008). For the Deaf children who use sign language as their L1, and who particularly hailed from non-signing hearing parents, the main goal would be to set up a language environment that will enable them to be educated with a sufficient language contact in depth and breadth with native signers such as signing educators who may serve as their language role models. In order to fulfill these goals and prepare individuals to use sign language to teach scholastic subjects in L1 classrooms, sign language TPPs are necessary.

Program considerations for TPPs

Worldwide, the teacher preparation programs in L1 sign languages are largely housed in programs in Deaf education. However, the development of teacher preparation programs in Deaf education has been controversial due to different language approaches. Most programs were designed in the tradition of oral approaches in the US (Israelite & Hammermeister, 1986) and Europe. In such programs, sign language was given either minimal or no consideration. Since the 1980s, there is an increase in the number of TPPs that offer sign language in their curriculum (Jones & Ewing, 2002). The TPPs in Germany slowly embed sign language in its curriculum since the 1990s (Günther & Schäfke, 2004).

The demographic changes among Deaf learners that led to increased diversity and heterogeneity, coupled with the inclusion movement in special education, have become issues that impact on the structure and content of Deaf TPPs in general (Swanwick et al., 2014). As Johnson (2013) remarked,

That history is one of need, opportunities, accomplishments, and controversies. It is not one of consensus, collaboration, or responsiveness to the changing demographics, educational placements, or instructional needs of learners who are Deaf and hard of hearing.

Ibid.: 440

In our experience, the shift from a single approach, such as the oral approach, to a different approach takes time, and needs political influence and patience. Setting up a second pillar, which is sign language, does not imply setting up an additional isolated route, but building bridges between spoken language- and sign language-oriented approaches. In most cases, these programs are bilingual programs. Furthermore, there is an “ever-expanding array of knowledge, skills, and experiences needed by teachers of learners who are Deaf and hard of hearing” (Johnson, 2013: 441). Teachers should be equipped to prepare learners to a life after school. This requires the teachers to acquire communicative competencies, problem-solving abilities, and collaboration skills.

Teachers from TPPs in L1 sign language should have an open and positive attitude and a keen interest in not only teaching but also using sign language to teach scholastic subjects. In addition to a high level of language competence, their attitude is closely linked to their contacts and commitment to the sign language community. The TPPs need to make political decisions on expectations for their learner-teachers. Its success is dependent on the political climate of the societies where Deaf education is offered. For instance, in 1981 the Swedish parliament agreed on an overall bilingual approach and called for a bilingual shift within the TPPs and the school curriculum (Svartholm, 1993).

The UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (UNCRPD, 2006a), which was ratified by 174 countries including member states of the European Union, except Ireland,1 proclaimed that people who are Deaf have the same human rights as every person in all areas of life. These rights include the right to receive education. In addition, Article 24 of the UNCRPD is dedicated to education and called for qualified sign language teachers to facilitate “the learning of sign language and the promotion of the linguistic identity of the Deaf community” (UNCRPD, 2006b). In this light, teachers, in particular Deaf teachers, should be recruited for all levels of education and receive training to become educators in sign language, Deaf culture, and teaching methods for Deaf children using sign language as the language of instruction. The presumption is that Deaf children, in their language and cultural realities, are bilingual and bicultural (Grosjean, 1992, 2010). Bilingual-bicultural approaches are and should be important parts of TPPs.

There is a “two-sided” qualification for L1 sign language teachers. On the one hand, there is the formal qualification in the areas of linguistics, Deaf Studies, sign language assessment, sign language teaching, sign language curriculum development, language acquisition, and research. On the other hand, there is the issue of involvement with the linguistic and cultural community to build positive attitudes towards Deaf people. The issue regarding the involvement of future L1 sign language teachers in the Deaf community, particularly if they are not Deaf themselves, is challenging for sign language TPPs on whether it can be fostered within the TPPs. This issue needs to be resolved in the process of planning and developing a L1 sign language TPP. De Weerdt, Salonen, and Liikamaa (2016) sum up their desired profile of a sign language teacher teaching sign language as L1. For them, the teachers should have an open and positive attitude and a keen interest in teaching sign language. In addition to a high level of language competence, the teachers should maintain contact with, and be committed to the sign language community.

Looking around: international perspectives

Arguments in support of TPPs in L1 sign language are given in the previous section. The following is an exposition of L1 sign language TPPs and the qualifications of L1 sign language teachers around the globe. It seeks to explore who offers the TPPs and how the teachers become qualified.

Who offers L1 sign language TPPs?

L1 sign language teacher preparation, qualifications, and development programs are mainly offered through universities, colleges, temporary projects, and other providers, such as initiatives by the Deaf community. In most cases, it is difficult to ascertain if a TPP prepares L1 sign language teachers, or sign language teachers for the education of Deaf learners in general. The authors could not identify a single program that focuses mainly on the qualification on L1 sign language teachers. The TPPs in sign language Deaf education are the focus in the ensuing discussion.

How are L1 sign language teachers qualified?

The TPPs that are offered have varied in timeframe, prerequisites, content, and emphasis on sign language. They are described below.

Timeframe. Existing TPPs in Deaf education with emphasis in L1 sign language worldwide vary in timeline for completing program requirements. The programs offered can roughly be separated into full-time and part-time programs. Full-time programs include bachelor or master degrees. Examples of existent full-time sign language Deaf education TPPs are Gallaudet, Madonna University, Boston University, and the California State University at Northridge in the US, Berlin University in Germany, and the University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg in South Africa. Learners who enroll in part-time programs start their practical teaching experiences and earn credentials as fully qualified teachers of Deaf children. Part-time programs are available for teachers who hold teaching credentials, which may or may not be for teaching Deaf children, and who enroll for courses in deaf education, sign language, and using sign language in teaching scholastics. Examples of part-time TPPs are the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, the La Trobe University in Australia, Gallaudet University, and McDaniel College in the US, and at the Universities of Hamburg and Cologne in Germany. A possible advantage of part-time programs is that the teaching experience that learners bring with them to TPPs enables them to directly link their newly gained theoretical knowledge to the actual education of Deaf learners.

Prerequisites. The existing L1 sign language TPPs also vary in the prerequisites for enrollment. Some part-time programs require individuals to hold a basic teaching degree and/or experience in working with Deaf children. Other part-time programs require a certain level of sign language skills. Gallaudet University’s ASL diagnostics and evaluation services assess individuals’ signing skills and attain Level 4 of the American Sign Language Proficiency Interview (ASLPI) scale. Madonna University accepts learners with an Intermediate American Sign Language II level. The Deaf applicants at Hamburg University need to demonstrate skills in German Sign Language at the C1 level based on the Common European Framework Reference for Languages (CEFR). The University of Berlin also assesses the sign language proficiency of their applicants. In addition, almost all TPPs are open to learners of any hearing status. A few programs are exclusively designed for Deaf learners. Examples are Hamburg University in Germany and Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand.

Content. While there are variations among TTPs in timeframe and prerequisites, there are some similarities in the content of the TPPs. There are some TPPs that focus on the acquisition and teaching of sign language. The TPPs that offer coursework in L1 sign language teaching are Madonna and Gallaudet University in the US, Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg in South Africa, and Cologne University in Germany. Other TPPs are designed as “mixed models” and include course topics such as auditory-oral approaches and spoken and written language literacy. Such TPPs are found in a special education course offered by the University of Newcastle in Australia and in the Program in the Teaching Learners who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing at the Ontario College of Teachers in Canada. They are not considered as the TPPs that offer L1 sign language teacher preparation.

Linguistics. In order to be able to teach sign language, knowledge in sign language linguistics is needed. TPPs include either specific courses in the linguistic structure of sign languages, such as offered in the Deaf education program at Gallaudet University, or combined courses in linguistics with sign language instruction, such as offered at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa.

Deaf Studies. The academic field of Deaf Studies comprises interdisciplinary approaches to the study of Deaf individuals, communities, and cultures as they have evolved within a larger context of power and ideology. The TPPs that offer L1 sign language teacher preparation tend to include Deaf Studies curricula. They include courses such as literary tradition in the Deaf community, Deaf culture and society, sign language in society, Deaf literature and Drama, and Deaf folklore. The coursework offers perspectives from anthropology, linguistics, literary theory, bilingual education, and cultural studies that revolve around gender, disability, and ethnic studies. Although this wide diversity of disciplines offers multiple perspectives, the field’s fundamental orientation is derived from the notion that Deaf people are not defined by their lack of hearing, but by linguistic, cultural, and sensorial ways of being in the world (Bauman & Murray, 2010).

Sign language assessment. Teachers need to be able to assess the learners’ sign language learning development. The TPPs that have been surveyed in the above include courses in sign language assessment instruments and procedures. The assessment of any sign language proficiency is impeded by an insufficient number of standardized assessments tools. An overview of existent L1 sign language assessment instruments can be found in the Sign Language Assessment Instruments website (www.signlang-assessment.info/index.php/tests-of-l1-development.html). The listed instruments were designed to assess the development of a sign language as L1 in Deaf children and subsequently plan intervention if needed.

Sign language teaching. The TPPs that are surveyed offer not only theoretical coursework but also offer practicum coursework in sign language teaching. The practicum courses provide an overview of instructional strategies and materials. Some TPPs offer courses such as methods on sign language teaching, and they are found at La Trobe University in Australia and at Gallaudet University in the US. Other TPPs offer practicum coursework in not only L1 sign language but also bilingual and L2 teaching, such as Boston University in the US, University of Newcastle in Australia, and in Berlin and Cologne, both in Germany.

Sign language curriculum development. Teaching methods are embedded within a sign language curriculum. A sign language curriculum includes concepts, domain areas, lesson structures, and instructional materials that involve the use of L1 sign language to teach scholastic subjects. There is a variation among TPPs in whether they offer coursework in L1 sign language curriculum. Some TPPs, such as Gallaudet University, Boston University, and the Victoria University of Wellington, offer coursework in L1 sign language curriculum.

Language acquisition. In order to assess the learners’ language development and provide appropriate sign language teaching, an understanding of the acquisition of sign language is necessary. Courses in language acquisition provide information on the linguistic concepts of languages and the stages and processes in mastering its linguistic features. This includes sign language and its acquisition by individuals who are Deaf. Many TPPs include courses on general language acquisition in their programs. Gallaudet University and the University of Hamburg offer courses in L1 acquisition.

Research. A few TPPs include a course in research. The course tends to include information on research inquiry, research designs, and protocols for conducting research studies. In the course, learners connect not only sign language research with practice but also practice with research. They are offered at Boston University and Gallaudet University.

Practicum. Particularly in the full-time TPPs identified in the above, learners with no prior working experience with Deaf children prior to enrollment are required to undergo a practicum or internship experience. Practical experiences enable learners to apply in practice their acquired theoretical knowledge in sign language teaching. In practicum seminars, they bring back their teaching experience for further analysis and reflection. The course provided by the University of Hamburg is not inevitably designed for teaching German Sign Language at a school for Deaf children.

Current issues in L1 sign language teacher qualification and development

Besides the academic qualification of sign language teachers, one issue remains about the preparation of some L1 sign language teachers. In some countries, such as Germany, non-academically qualified sign language teachers work at schools teaching sign language. This presents a question regarding the qualifications of the non-academically trained Deaf sign language teachers (De Weerdt, Salonen & Liikamaa, 2016). Another issue regards the continuing professional development of qualified L1 sign language teachers. They need to continually update themselves on new developments in sign language teaching and research. There are resources that the teachers can access for the new developments. For example, the website www.signteach.eu was designed for sign language teachers as well as educators for sign language teachers. It provides resources for sign language teaching such as lesson plans and podcasts, and information such as conferences, presentations, and publications. The video inserts in the website are shown in different European sign languages and International Sign.

Pedagogical applications

In recent years, the demand for sign language teaching in Deaf schools had increased. There is a shortage of L1 sign language teaching material. There are insufficient training opportunities for current and future teachers in sign language studies or related fields that would allow them to amplify their knowledge of sign language linguistics, pedagogy, and other qualification areas that are discussed in the above. There is a need to increase the number of TPPs that focus on the use of L1 sign language pedagogy for scholastic subjects, and to develop L1 sign language teaching materials. One example of a TPP that proffers resources, coursework, and practicum experiences for individuals who want to become L1 sign language teachers is at the University of Cologne. The program is described below.

L1 sign language TPP at the University of Cologne

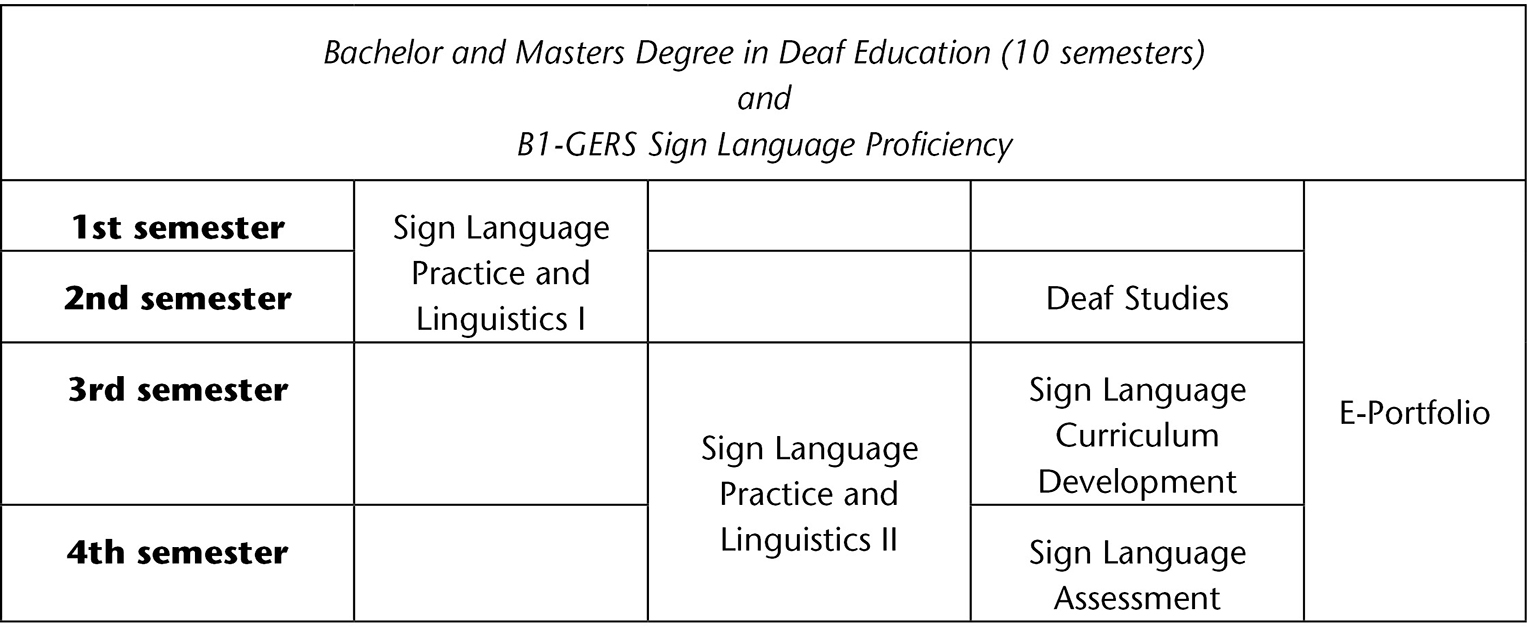

As Borgardt points out, “besides bilingual teaching, the subject DGS [German Sign Language] is the other important pillar of sign language at school” (Borgardt, 2012: 393; quotation translated from German). For Borgardt, sign language as a subject should be offered in bilingual teaching just like hearing German native speakers in German-speaking countries join compulsory German classes throughout their school years. Influenced by this quote, a working group headed by Kaul at the University of Cologne designed a program to qualify educators to teach DGS as a subject with a focus on DGS as a L1. In 2015 the first group of teachers enrolled for the additional subject DGS (Kaul, Griebel, & Klinner, 2016). The program is designed for four semesters, the equivalent of two years. The timeline in the University of Cologne L1 Sign Language TPP is shown in Figure 2.1.

DGS as a subject is currently under plan as an additional course within or on top of Cologne’s current Deaf Education teaching degree program.

The prerequisite for enrollment in the program is a Masters degree in Deaf education, which is also offered at Cologne. Cologne’s Master of Arts program in Deaf education includes coursework and practicum in special education with a focus on Deaf education. The coursework in the Deaf education program includes theories of teaching, curriculum, and assessment, and the socialization and communication of Deaf children. The coursework provides the foundation for the teaching of DGS as a subject matter. In addition, a screening was developed to test the applicants’ proficiency in DGS. The learners need to attain an entry level of B1 of the CEFR in DGS. The areas of language competence were assessed in conjunction with CEFR, and they are reception, production, and interaction. Applicants that satisfy both prerequisites are eligible to join the program.

The program consists of four main subject areas: German Sign Language linguistics, Deaf Studies, sign language curriculum development, and sign language assessment.

German sign language linguistics I and II

In this module, the learners learn linguistic theories and approaches, and develop competencies in the features and structures of DGS including phonology, morphology, syntax, pragmatics, and text linguistics. This linguistic competence is designed to enable the learners to improve their DGS signing skills and reach C1 Level of the CEFR, which assesses their ability to understand complex and longer texts in DGS.

Deaf studies

In this course in Deaf Studies, learners learn about the historic development of sign language at schools, the history of sign language teaching, and the history, culture, and challenges of the sign language community. Built on their previous knowledge on the socialization of Deaf children from other Deaf education courses, the learners also learn about the social environment of Deaf children. The learners also learn about resources that emphasize Deaf empowerment, enable Deaf children to get involved with the sign language community, and develop their identities outside of the school setting. Examples of the resources for the Deaf children are the Deaf youth organizations and camps such as the European Union of the Deaf Youth (EUDY), and Frontrunners deaf camp in Denmark.

Sign language curriculum development

In the sign language curriculum development course, learners learn about theories and practices in sign language curriculum. They apply what they learned about DGS linguistic structures and Deaf Studies and develop sign language curricula, lesson plans, and instructional materials for their L1 sign language teaching. They also evaluate and adapt teaching materials for differentiated instruction to Deaf children with heterogeneous learning and communicative characteristics.

Sign language assessment

This course is an introduction to sign language assessment and its psychological, linguistic, and sociolinguistic domains. As mentioned earlier, there are a few standardized assessment tools available in L1 sign language. In the course, the learners apply their linguistic and diagnostic knowledge to the design of sign language assessment. They learn to develop qualitative, individualized sign language assessment tools in congruence with the different profiles and social and communicative backgrounds of different learning groups. They will learn to analyze assessment results to ascertain sign language development, acquisition, and proficiency of the L1 sign language users.

E-portfolio

The Cologne L1 Sign Language TPP provides learners with an e-portfolio. Throughout the four semesters, learners collect, record, brainstorm, and elaborate ideas, discussions, and content in the courses in the e-portfolio. The e-portfolio is used as a platform where the learners reflect on what they learn and connect theoretical knowledge with teaching experiences.

One of the crucial questions regarding sign language teaching is who is allowed to teach sign language. The most important is the qualification of the sign language teacher regardless of his or her hearing status. They need to have pedagogical and methodological skills, and the ability to teach sign language and Deaf culture in an authentic way. Deaf teachers may have the advantage to offer learners an authentic and enriching experience to learn sign language based on their special insights into Deaf culture. Hearing sign language teachers do bring special strengths to the learning experience for learners. They can function as an ambassador for the “hearing world” by showing understanding for Deaf culture through interaction within the Deaf community and their ability to communicate in sign language at a competent level of proficiency.

The TPPs discussed above share some similarities regarding the content of the programs. Most programs include theoretical and pedagogical course offerings in linguistics, Deaf Studies, sign language assessment, sign language acquisition, sign language teaching, sign language curriculum development, research, and practicum experiences. However, several gaps remain in TPP programs that can be addressed in future research studies and pedagogical practices.

Future trends

Research studies and pedagogical applications are closely linked. If evidence-based practices are provided, effective pedagogical applications can be realized and highly qualified future teachers can be successfully trained. For future research as well as the teaching in the classroom, the question regarding the direction sign language TPPs is: Are the programs designed for teaching learners who are users of L1 sign language?

Future research studies

Late sign language learners represent an increasing part of sign language learner group. The preparation of future sign language teachers need to be able to offer an adequate, data-based language education for this group. In case of the preparation of L1 sign language teachers, research on late learners’ sign language development is lacking since the main focus on L1-sign language acquisition had been on the early language development of Deaf children of Deaf parents. Research is needed in the language development of late L1 sign language learners. Once data becomes clearer, the quality of sign language educators and their teaching can be further enhanced.

There are currently no assessment instruments and protocols for evaluating L1 sign language TPP programs. They are needed to assess whether they prepare effective teachers using L1 sign language to teach scholastics, including sign language. A TTP evaluation instrument needs to be developed (cf. Jacobowitz, 2005) with information on the assessment items that can be garnered from sign language TPP learners, alumni, and teacher educators. Results of TPP evaluation may provide information for improving the quality of TPPs.

Future pedagogical practices

The content of teacher preparation courses should include information about the variegated target groups that are to be taught by the future sign language teachers. More specifically, there is the necessity to develop or modify in courses with information in linguistic, psychological, sociological, and pedagogical theories and evidence-based sign language pedagogical tools including assessment tools and teaching methods that are adapted to the heterogeneous and bilingual groups of young sign language users.

Many universities require the passing of a sign language proficiency test as a prerequisite for enrollment in specific courses. Some develop their own assessment instruments with their own standards. Others use common standards such as the CEFR for designing their own assessment instruments. There is a need to create a national sign language proficiency interview and a standardized test of knowledge of sign language within countries and for their sign languages. Data from national sign language proficiency interviews may enable comparisons of the proficiency of sign language teachers. A standardized sign language test containing domains and scope that model after the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL), which assesses reading, listening, speaking, and writing skills in the English language, may provide clarity to the assessment of the teachers’ sign language proficiency.

A platform with database of TPPs that provide L1 sign language teaching education needs to be developed for inter-TPP collaboration and support in research and practice. With continued research in the area of L1 sign language acquisition, coupled with a sharper focus on L1 sign language teaching and teacher qualification, the preparation of teachers to use sign languages to teach scholastic subjects to young users of L1 sign languages can be improved. Only if sign language teachers accept sign language as part of their individual language repertoire, they accept the persons they teach, and offer the language input needed as what the Danish Bonaventura Parents’ Organization hoped that every good teacher strives for and teach Deaf children in the way they deserve.

Note

References

Ahlgren, I. (1994). Bilingualism in Deaf Education. Hamburg: Signum Verlag.

American Sign Language Teachers Association (2013). Guidelines for hiring ASL teachers. Retrieved July 25, 2017 from: https://aslta.org/employment/find-a-teacher/guidelines-for-hiring-asl-teachers/

Anderson, D. (2006). Lexical development of deaf children acquiring signed languages. In B. Schick, M. Marschark, & P. E. Spencer (eds.), Advances in the Sign Language Development of Deaf Children (pp. 135–60). New York: Oxford University Press.

Auslan LOTE (n.d.). Auslan LOTE curriculum and support material. Retrieved July 25, 2017 from www.signplanet.net/AdultsDesk/AuslanLOTE.asp

Baumann, H-D.L., & Murray, J.J. (2010). Deaf studies in the 21st century: “Deaf gain” and the future of human diversity. In M. Marschark & P.E. Spencer. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies, Language, and Education (Vol. 2) (pp. 210–25). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Borgardt, Christian (2012). Gebärdensprachpädagogik: DGS im bilingualen Schulunterricht. In H. Eichmann; M. Hansen, & J. Heßmann. Handbuch Deutsche Gebärdensprache: Sprachwissenschaftliche und anwendungsbezogene Perspektiven (pp. 381–97). Signum: Hamburg.

Boudreault, P., & Mayberry, R.I. (2006). Grammatical processing in American Sign Language: Age of first-language acquisition effects in relation to syntactic structure. Language and Cognitive Processes, 21 (5), 608–35.

Chen Pichler, D. (2012). Acquisition. In R. Pfau, M. Steinbach, & B. Woll (eds.), Sign Language (pp. 647–86). Boston: De Gruyter.

Cormier, K., Schembri, A., Vinson, D., & Orfanidou, E. (2012). First language acquisition differs from second language acquisition in prelingually deaf signers: Evidence from sensitivity to grammaticality judgement in British Sign Language. Cognition, 124 (1), 50–65.

Council of Europe (2017). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). Retrieved July 25, 2017 from www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages

Dammeyer, J., & Marschark, M. (2016). Level of educational attainment among deaf adults who attended bilingual-bicultural programs. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 21 (4), 394–402.

De Houwer, A. (2009). Bilingual First Language Acquisition. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

De Weerdt, D., Salonen, J., & Liikamaa, A. (2016). Raising the Profile of Sign Language Teachers in Finland. Kieli, koulutus ja yhteiskunta, conference April 15, 2016 (Huhtiku). Retrieved July 25, 2017 from www.kieliverkosto.fi/article/raising-the-profile-of-sign-language-teachers-in-finland/

Emmorey, K. (2002). Language, Cognition and the Brain: Insights from Sign Language Research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Figueras, B., Edwards, L., & Langdon, D. (2008). Executive function and language in deaf children. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 13 (3), 367–77.

Galvan, D. (1999). Differences in the use of American Sign Language morphology by deaf children: Implications for parents and teachers. American Annals of the Deaf, 144 (4), 320–24.

Grosjean, F. (1992). The bilingual & the bicultural person in the hearing and in the Deaf world. Sign Language Studies, 77 (1), 307–20.

Grosjean, F. (2010). Bilingualism, biculturalism, and deafness. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 13 (2), 133–45.

Günther, K.B., & Schäfke, I. (eds.). (2004). Bilinguale Erziehung als Förderkonzept für gehörlose SchülerInnen: Abschlussbericht zum Hamburger bilingualen Schulversuch. Hamburg: Signum.

Günther, K.-B., & Hennies, J. (2011). Bilingualer Unterricht in Gebärden-, Schrift- und Lautsprache mit hörgeschädigten Kindern. Zwischenbericht zum Berliner Bilingualen Schulversuch. Hamburg: Signum.

Hänel-Faulhaber, B. (2012). Gebärdenspracherwerb: Natürliches Sprachenlernen gehörloser Kinder. In H. Eichmann, M. Hansen, & J. Heßmann (eds.), Handbuch Deutsche Gebärdensprache. Sprachwissenschaftliche und anwendungsbezogene Perspektiven (pp. 293–310). Hamburg: Signum.

Hauser, P.C., Lukomski, J., & Hillmann, T. (2008). Development of deaf and hard-of-hearing learners’ executive function. In M. Marschark, & Peter C Hauser (eds.), Deaf Cognition: Foundations and Outcomes (pp. 286–308). New York: Oxford University Press.

Hintermair, M. (2014). Psychosocial development in deaf and hard-of hearing children in the twenty-first century: Opportunities and challenges. In M. Marschark, G. Tang, & Knoors, H. (eds.), Bilingualism and Bilingual Deaf Education (pp. 152–186). New York: Oxford University Press.

Institut für Deutsche Gebärdensprache. (2016). GeR-DGS – Gemeinsamer Europäischer Referenzrahmen für Deutsche Gebärdensprache. Retrieved July 25, 2017 from www.idgs.uni-hamburg.de/images/ger-dgs/globalskala-ger-dgs-05-11-13.pdf

Israelite, N.K., & Hammermeister, F.K. (1986). A survey of teacher preparation programs in education of the hearing impaired. American Annals of the Deaf, 131 (3), 232–237.

Jacobowitz, L.E. (2005). Language teacher preparation programs in the United States. Sign Language Studies, 6 (1), 76–110.

Jankowski, K.A. (1997). Deaf Empowerment. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Johnson, H.A. (2013). Initial and ongoing teacher preparation and support: Current problems and possible solutions. American Annals of the Deaf, 157 (5), 439–449.

Jones, T.W., & Ewing, K.M. (2002). An analysis of teacher preparation in deaf education: Programs approved by the Council on Education of the Deaf. American Annals of the Deaf, 147 (5), 71–78.

Kaul, T., Griebel, R., & Klinner, L. (2016). Einführung des Studiengangs “Deutsche Gebärdensprache als Unterrichtsfach” an der Universität zu Köln. Das Zeichen, 30 (102), 96–99.

Klima, E.S., & Bellugi, U. (1979). The Signs of Language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Knoors, H., & Marschark, M. (2012). Language planning for the 21st century: revisiting bilingual language policy for deaf children. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 17 (3), 291–305.

Koester, L.S. (1995). Face-to-face interactions between hearing mothers and their deaf or hearing infants. Infant Behavior and Development, 18 (2), 145–53.

Koester, L.S., & Lahti-Harper, E. (2010). Mother-infant hearing status and intuitive parenting behaviors during the first 18 months. American Annals of the Deaf, 155 (1), 5–18.

Lederberg, A.R., & Spencer, P.E. (2001). Vocabulary development of deaf and hard of hearing children. In M.D. Clark, M. Marschark, & M.A. Karchmer (eds.), Context, Cognition, and Deafness (pp. 88–112). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Lederberg, A.R.; Schick, B., & Spencer, P.E. (2013). Language and literacy development of deaf and hard-of-hearing children: successes and challenges. Developmental Psychology, 49 (1), 15–30.

Lillo-Martin, D. (2015). Sign language acquisition studies. In E.L. Bavin & L.R. Naigles (eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Child Language (2nd ed.) (pp. 504–26). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mayberry, R.I. (1993). First-language acquisition after childhood differs from second-language acquisition: The case of American Sign Language. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 36, 1258–70.

Mayberry, R.I., & Lock, E. (2003). Age constraints on first versus second language acquisition: Evidence for linguistic plasticity and epigenesis. Brain and Language, 87 (3), 369–84.

Mitchell, R.E., & Karchmer, M.A. (2004). Chasing the mythical ten percent: Parental hearing status of deaf and hard of hearing learners in the United States. Sign Language Studies, 4 (2), 138–63.

Morgan, G., & Woll, B. (eds.). (2002). Directions in Sign Language Acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Morgan, G., Meristo, M., Mann, W., Hjelmquist, E., Surian, L., & Siegal, M. (2014). Mental state language and quality of conversational experience in deaf and hearing children. Cognitive Development, 29, 41–9.

Newport, E.L. (1988). Constraints on learning and their role in language acquisition: Studies of the acquisition of American Sign Language. Language Sciences, 10 (1), 147–72.

Ortega, G. (2016). Language acquisition and development. In G. Gertz, & P. Boudreault (eds.), The SAGE Deaf Studies Encyclopedia (pp. 547–51). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pickersgill, M., & Gregory, S. (1998). Sign Bilingualism: A Model. Wembley, UK: Adept Press.

Plaza-Pust, C., & Morales-López, E. (eds.). (2008). Sign Bilingualism. Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Pribanic, L. (2006). Sign language and deaf education: A new tradition. Sign Language and Linguistics, 9 (1/2), 233–54.

Sandler, W., & Lillo-Martin, D. (2006). Sign Language and Linguistic Universals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schein, J.D. (1987). The demography of deafness. In P.C. Higgins & J.E. Nash (eds.), Understanding Deafness Socially (pp. 3–27). Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Schick, B. (2011). The development of American Sign Language and manually coded English systems. In M. Marschark & P.E.Spencer (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies, Language, and Education (Vol. 1) (pp. 229–40). New York: Oxford University Press.

Singleton, J.L., & Morgan, D.D. (2006). Natural signed language acquisition within the social context of the classroom. In B. Schick, M. Marschark, & P.E. Spencer (eds.), Advances in the Sign Language Development of Deaf Children (pp. 344–75). New York: Oxford University Press.

Spencer, P.E. (2003). Parent-child interaction: Implications for intervention and development. In B. Bodner-Johnson, & M. Sass-Lehrer (ed.), The Young Deaf or Hard of Hearing Child: A Family-centered Approach to Early Education (pp. 333–68). Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Stokoe, W.C. (1960). Sign Language Structure: An Outline of the Visual Communication System of the American Deaf. Studies in Linguistics Occasional Papers #8, University of Buffalo.

Svartholm, K. (1993). Bilingual education for the deaf In Sweden. Sign Language Studies, 81 (1), 291–332.

Swanwick, R. (2015). Deaf children’s bimodal bilingualism and education. Language Teaching, 49 (1), 1–34.

Swanwick, R., Hendar, O., Dammeyer, J., Kristoffersen, A.-E., Salter, J., & Simonsen, E. (2014). Shifting contexts and practices in sign bilingual education. In M. Marschark, G. Tang, & H. Knoors (eds.), Bilingualism and Bilingual Deaf Education (pp. 292–310). New York: Oxford University Press.

UNCRPD. (2006a). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Retrieved July 25, 2017 from https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-15&chapter=4&clang=_en

UNCRPD. (2006b). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Retrieved July 25, 2017, from www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html