20

L2/Ln parent sign language education

Kristin Snoddon

Introduction

Teaching sign language as a second (L2) or additional (Ln) language to hearing parents, who are not native users of sign languages, of deaf children is an underexplored area of research. A number of projects internationally have been initiated that are aimed at supporting the parents’ acquisition of sign language. However, in many contexts there has often been a shortage of formal, sustained programs and curricula that are targeted at parents of deaf children and a lack of a body of evidence to document the success and outcomes of parents’ sign language learning. However, over 90% of deaf children are born to hearing parents who may have little or no knowledge of sign language (Mitchell & Karchmer, 2004), and the stated focus of neonatal hearing screening and early intervention services for deaf children is supporting language development (Speech-Language & Audiology Canada, 2014; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013). Moreover, the benefits of sign language for deaf children’s linguistic, cognitive, and social and emotional development are well documented (e.g., Kushalnagar et al., 2010). The lack of comprehensive public support for parents’ learning of sign language in many contexts is here argued to be a main factor behind the failure of many parents to learn sign language to better communicate with their deaf child. Most sign language classes for second or additional language learners do not address parents’ specialized learning needs. These needs include developing elaborated parent-child communication, supporting deaf children’s social and emotional development, and fulfilling parenting roles via sign language. The development of specialized parent sign language classes and curricula in turn relies on enhanced support for sign language teacher training and teaching materials development.

This chapter provides an overview of theoretical and ideological perspectives on teaching sign language as a L2/Ln to hearing parents of deaf children, including parent advocacy for bilingual education, home visiting frameworks, and parent learning goals and motivation. A historical survey of international initiatives is presented from Australia, the US, the Netherlands, and Scandinavian countries that aimed at supporting parents’ sign language learning. The outcomes of these initiatives are evaluated, and future directions are suggested for research and practice in parent sign language education.

Theoretical perspectives

This section discusses theoretical perspectives in parent sign language education in relation to bilingual education for deaf children, home visiting services to deaf children and their families, teacher goals and learner motivation, and plurilingualism. Parent sign language education is linked to advocacy for and provision of bilingual education for deaf children, which privileges the teaching of native sign languages and written (and sometimes spoken) national languages and the cultural norms of deaf and hearing communities (Czubek & Snoddon, 2016). However, in other contexts teaching sign language to parents of deaf children takes place within a home visiting services framework that may limit parents’ learning opportunities. Both teacher goals and learner motivation in parent education revolve around the need to support communication between parents and deaf children. A theoretical framework of plurilingualism takes an action-oriented and learner-centered approach to parent sign language education. These topics, theories, and concepts are further exemplified below.

Policy context and parent advocacy in Scandinavia

Several Scandinavian countries where bilingual education for deaf children historically enjoyed widespread support have implemented intensive sign language instruction for parents of deaf children. Parents of deaf children, along with national associations of deaf and hard of hearing people and university researchers in sign language linguistics, were a driving force behind Sweden’s becoming one of the first countries in the world to recognize sign language in legislation (Nilsson & Schönström, 2014; Svartholm, 2010). In Denmark, the Bonaventura Parents’ Organization issued a memorandum outlining the following “basic attitudes” or principles for parents of deaf children that emphasize a bilingual approach and inform education and other services to be provided to parents of deaf children:

- Deaf children are children;

- Deaf children’s language is sign language;

- Deaf children are not ill;

- Deaf children become deaf adults;

- Deaf children should be together with deaf people;

- Deaf children should be together with hearing people;

- Parents of deaf children need each other;

- The impact of a deaf child is on the family (see Mahshie, 1995: 235–8).

These principles subsequently became a foundation for early sign language intervention in other countries, including Finland (Takala, Kuusela, & Takala, 2000).

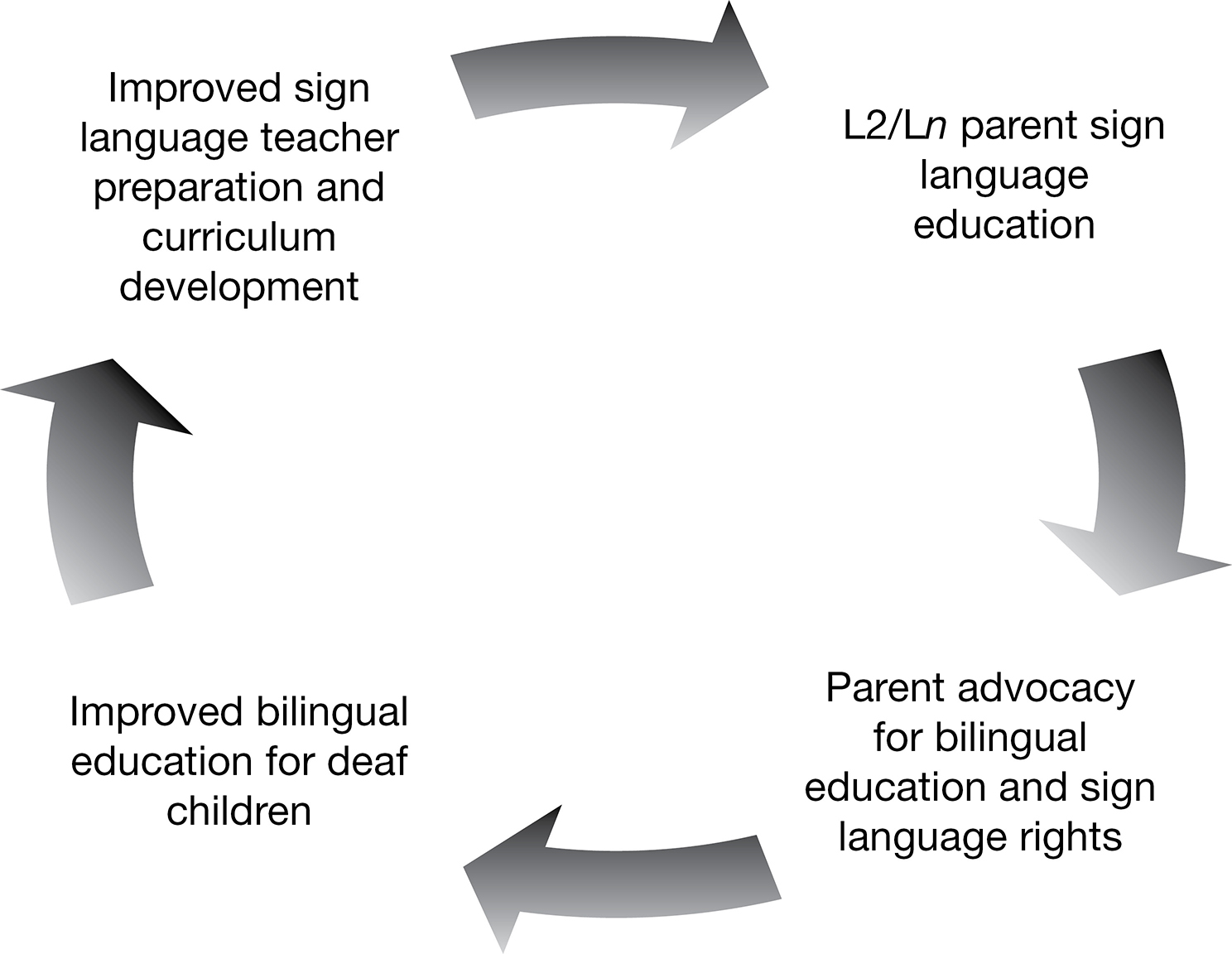

Parents’ ability to access adequate support for sign language learning is directly linked to their increased advocacy for deaf children’s bilingual education. In turn, bilingual education for deaf children is linked to better sign language teacher preparation and curriculum development. Figure 20.1 shows the cycle of L2/Ln parent sign language teaching and advocacy.

Figure 20.1The cycle of L2/Ln parent sign language teaching and advocacy

Currently, Swedish law requires sign language instruction to be provided for “persons who require sign language,” including parents of deaf children (Svartholm, 2014: 44). However, today in Sweden and many other countries in the Global North, most deaf children receive cochlear implants, and as a consequence an increasing number of parents do not feel sign language is needed, at least in early childhood (Nilsson & Schönström, 2014). This presents a risk to these children’s healthy development since language deprivation may result (Humphries et al., 2012).

Home visiting frameworks

In other contexts in the Global North, approaches to supporting parents’ sign language learning tend to be relatively informal and unstructured, especially compared to learning opportunities for preservice sign language interpreters and other second or additional language learners studying at postsecondary institutions. Often, these approaches focus on home visiting services by deaf mentors or consultants who support deaf children’s language development through play and informal teaching (e.g., Watkins, Pittman, & Walden, 1998). In the United States and Canada, many state and provincial schools for the deaf and their associated regulatory bodies provide home visiting and outreach services to preschool-age deaf children and their families (e.g., Roberts, 1998). The Colorado Home Intervention Program is a notable example of a home visiting program that provides a range of intervention services to parents of deaf children that focus on sharing information about “resources, strategies, development, and methods of communication” (Yoshinaga-Itano, 2003: 13). Most early intervention providers for this program are licensed teachers of the deaf or special educators, speech-language pathologists, audiologists, social workers, and/or psychologists with graduate degrees, and there are also a number of service providers who teach sign language to parents (Yoshinaga-Itano, 2003). Within the early intervention services framework, these sessions take place once weekly for one to one-and-a-half hours (Yoshinaga-Itano, 2003).

Home visiting services to families with deaf children exist within a longstanding early intervention framework that revolves around family-centered principles and family health (Nicholson et al., 2016). However, the centering of parent sign language teaching within a health services framework constructed by infant hearing screening programs also shows how a medical model of disability is enacted within the lives of parents and deaf children, where “funding is linked to diagnostic labels, and education may be seen as ‘treatment’” (Komesaroff & McLean, 2006: 89). A health services framework may also have inhibited the development of innovative, theoretically grounded and research-based models of second and additional language teaching and learning of sign languages for parents of deaf children. This is reflected in the shortage of curricular and teaching materials directed at parents and the comparatively limited services available to this population. For example, the Ontario Infant Hearing Program’s model of providing up to 48 hours of American Sign Language (ASL) instruction per year until the child reaches the age of six, and half of this number of hours for families who choose a dual spoken and signed language approach, has resulted in parents’ reported communication difficulties and frustration (Snoddon, 2014a). In 2018, the Infant Hearing Program stated the consultants providing ASL and Langue des Signes Québécoise (LSQ) support and development services under the program “do not teach ASL/LSQ to families” (Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services, 2018: 16). In addition, it was announced that the dual signed and spoken language approach is no longer offered and that parents must choose either spoken or signed language services since “IHP services are not designed to support development of a child’s bilingualism in spoken and signed language” (ibid.: 7). This raises further questions as to how parents of deaf children in Ontario can receive research-based ASL learning support that meets their needs and fosters deaf children’s bilingual development.

Teaching goals and learner motivation in parent sign language teaching

Improved communication with deaf children is therefore a key factor in parents’ motivation as second or additional language learners of sign language. To this point, Young (1999) has addressed the impact of a cultural-linguistic model of deafness on parents’ adjustment to having a deaf child. In this model, parents and children’s sign language use and cultural identity are centered, and parents and children’s access to learning sign language and participating in the deaf community are paramount. However, the competing frameworks employed by deaf and hearing service providers have resulted in opposing views regarding parents’ attainment of sign language proficiency (Young, 1997). Young argued that a “linguistic proficiency” framework held by many hearing professionals, based in modernist conceptions of bilingualism as requiring balanced, native-like proficiency in standard languages, regards parents’ second or additional language learning of sign language as unrealistic and therefore to be discouraged (ibid.). This view continues to be held today by several researchers in deaf education (e.g., Knoors & Marschark, 2012; Mayer & Leigh, 2010). Young (1997) contrasted this framework with the “communicative competence” framework held by deaf professionals in her study who privileged parents’ communicative abilities over notions of formal linguistic proficiency. Nevertheless, Young (1997) found that parents of deaf children in her study expressed a desire to both become fluent in sign language and achieve communicative competence. This goal was reported by parents to not be well supported by the home visiting services they received (Young, 1997).

A plurilingual framework

Snoddon (2014a) proposed a learning framework of plurilingualism, or multilingualism at the level of the individual (Coste, Moore, & Zarate, 2009) for parents’ L2/Ln learning of sign language. This was “a response to certain academic and professional perceptions of parents’ learning of sign language as a second language as being unrealistic, unimportant, or contentious” (Snoddon, 2014a: 175). Plurilingualism

defended the (sociolinguistic) notion that because plurilingual individuals used two or more languages – separately or together – for different purposes, in different domains of life, with different people, and because their needs and uses of several languages in everyday life could be very different, plurilingual speakers were rarely equally or entirely fluent in their languages.

Coste, Moore, & Zarate, 2009: v

This defense of partial competence in a sign language was in part intended to counter negative perceptions of parents’ ASL abilities that were evident in parents’ own comments during interviews such as the following remark from a parent participant in Snoddon’s (2014a) study who had been receiving ASL home visiting services for over two years. As the participant stated of her young deaf child, “My concern is that I don’t know ASL, myself. She sees broken ASL, and she can’t hear enough English. So I feel she gets both broken English and broken ASL” (Snoddon, 2014a: 185).

Like Young’s (1997) findings, Snoddon (2014a) found a paradox in the need to simultaneously endorse parents’ emergent sign language competences while developing more rigorous, classroom-based models of sign language teaching to support better learning. While a home visiting model of parent sign language teaching remains predominant in many contexts that provide early intervention services, other models have been provided in the form of immersion programs that will be further discussed in the next section. More recently, work has taken place in the Netherlands and Canada to begin developing parent sign language curricula that are aligned with the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) as a framework for second language learning, teaching, and assessment (Oyserman & de Geus, 2013; Snoddon, 2015). The next section further discusses historical and current pedagogical practices and programs in parent sign language teaching, and research studies in their effectiveness.

Pedagogical practices

This section discusses how theories in parent sign language education are translated into practice in relation to the establishment of immersion programs for parents, the development of a specialized parent curriculum, deaf mentor home visiting services, and a deaf mentor curriculum. These pedagogical practices and concepts are further exemplified below.

Immersion programs in Scandinavia

In Scandinavian contexts, policy and practical changes for supporting bilingual education occurred in tandem with recognition of the importance of peer support for hearing parents of deaf children and interaction with other deaf children and adults (Mahshie, 1995). Summer courses in Swedish Sign Language for families with deaf children, dating from the 1970s, combine sign language instruction by deaf tutors for parents with summer camp activities for deaf children and hearing siblings (Nilsson & Schönström, 2014). These courses were organized by the Swedish National Association of the Deaf at its folk high school in Leksand (Nilsson & Schönström, 2014).

Mahshie (1995) similarly reported that both Sweden and Denmark implemented intensive parent courses taking place over either one week, two weeks, or on weekends. Historically, such intensive courses typically involved teaching sign language, storytelling, and gestural communication, and discussing child language (Ulfsparre, 1977). The courses were created to give support to the parents in communicating with their deaf children at home. This immersion-type program structure allowed the parents to concentrate on learning sign language in a setting away from home, and socialize with other parent learners while their children participated in a playgroup (Mahshie, 1995). The courses were organized in partnership between deaf schools, deaf clubs, parent organizations, and universities with support from community funding for individual parents, and were taught by teams of deaf teachers in Sweden and deaf and hearing teachers in Denmark (Mahshie, 1995). The Swedish and Danish Sign Language lessons focused on building receptive skills to help parents better understand their children and on supporting parents’ sense of communicative competence (Mahshie, 1995). In the 1990s, a national curriculum was launched for teaching Swedish Sign Language to parents of deaf children that totaled 240 hours (Nilsson & Schönström, 2014). These courses were offered in multiple ways, including an evening class format as well as the previously described weekend, weeklong, and summer camp settings. The Swedish National Association of the Deaf also worked with local deaf clubs to organize parent association meetings, parent courses, and social activities for families with deaf children (Mahshie, 1995).

Mahshie (1995) reported anecdotal findings regarding the impact of parent sign language instruction on parents’ attitudes toward sign language as well as parents’ second or additional language proficiency. As she wrote, “according to the preschool and first grade teachers I interviewed, a high percentage of parents in these countries DO learn enough of the language of the Deaf community to communicate high-level concepts to their children well before their children enter first grade” (Mahshie, 1995: 139, emphasis in original). As one parent reported in an interview, “Almost all parents of deaf children today in Sweden sign” (Mahshie, 1995: 141).

In Finland, Takala, Kuusela, and Takala (2000) described a five-year intervention project where deaf preschool-age children and hearing family members received sign language education. In this project, parents and deaf children received informal sign language lessons during home visits in addition to intensive weekend workshops taking place four times a year for parents, siblings, and relatives of deaf children (Takala, Kuusela, & Takala, 2000). Families with deaf children could in total receive up to one hundred hours of sign language lessons each year. The authors administered a questionnaire to parents that focused on children’s sign language competence in addition to parents’ learning experiences and the perceived benefits of sign language instruction. While the “parents generally reported experiencing a high level of benefit” and “were both satisfied with and eager to continue with the project” (Takala, Kuusela, & Takala, 2000: 369), with more benefits reported by parents who were more actively involved with learning, they “did not generally have a high opinion of their own ability to sign” (ibid.: 371). However, the authors reported: “Every one of the respondents learned to sign during the project” (ibid.: 371). Between the first and last years of the project, parents’ reported ability to have rich discussions with their deaf child increased, and parents stated that family communication became easier as they learned sign language, met other families with deaf children, and learned about deaf community and culture.

Similarly, in Norway parents of deaf and hard of hearing children are eligible to participate in a module-based program totaling 40 weeks during the child’s first 16 years (Peterson, 2007). This program teaches 900 hours of Norwegian Sign Language and 100 hours of topics related to parenting a deaf child (Peterson, 2007). Sign language instruction, room, and board are provided at no cost to parents at government resource centers (Peterson, 2007). Peterson (2007) reports an earlier study where he administered a survey to 723 parents of deaf children enrolled in this program, where 88% of parents reported better communication at home, 76% reported improved quality of family life, and 85% reported that they never considered quitting the course. However, Peterson (2007) reported that many parents, almost all of whom have children with cochlear implants, desired more instruction focusing on the simultaneous use of speech and sign. This finding suggests that the parents lack an understanding of the role of sign language in supporting spoken language development in deaf children with cochlear implants (Humphries et al., 2014).

An Auslan curriculum for families

Napier, Leigh, and Nann (2007) described an action research project for designing a new Australian Sign Language (Auslan) curriculum for hearing parents of deaf children. The authors reported that parents in their study had attended other Auslan classes for second- or additional-language learners that did not meet parents’ needs for communicating with deaf children. In addition to a specialized curriculum, the authors identified the need for parent sign language teaching to include information about raising a deaf child, reading books with deaf children through sign language, and learning deaf cultural norms such as visual and tactile behaviors to get a deaf person’s attention (Napier, Leigh, & Nann, 2007). Prior to developing their pilot Auslan for the Family curriculum, Napier, Leigh, and Nann (2007) undertook extensive consultation with parents and professionals where parents presented a range of issues, including the need for extended support for learning sign language beyond the early intervention period and information about sign language linguistics.

The Auslan for the Family curriculum was based on an existing Auslan teaching curriculum (ACTRAC, 1996) but included thematic modules deemed suitable for families and children because they focused on daily family activities and routines (Napier, Leigh, & Nann, 2007). The curriculum consisted of two levels to be completed in two years via a blended distance and in-person teaching approach via family home visits (Napier, Leigh, & Nann, 2007). The first level of the curriculum focused on vocabulary learning, with six modules about greetings and introductions, the home environment, everyday activities and routines, and deaf culture and community (Napier, Leigh, & Nann, 2007). The second module focused on supporting conversational skills, with six additional modules about meeting people, a school day, holidays, excursions, and deaf studies (Napier, Leigh, & Nann, 2007). An immersion component was included in both levels where family members attended social gatherings with other parents and deaf children, as well as other members of the deaf community. The final module featured a one-day workshop about communication, play, and reading with deaf children. This included information about attention-getting strategies and visual communication. Parents also received a video resource package that featured deaf adults signing with children while reading books.

Perhaps owing to the curriculum’s focus on home visits and distance learning, a chief finding of Napier, Leigh, & Nann’s (2007) project appears to be a continuing need for additional video resources to support families’ learning of Auslan, specifically Auslan translations of children’s books. No data is provided regarding parents’ sign language learning outcomes following the new curriculum, however, which is reported to have “had only limited implementation” (Napier, Leigh, & Nann, 2007: 97).

American Sign Language initiatives

Similar to the Australian context, in the United States ASL teaching for parents has largely taken place within a home visiting early intervention framework. Watkins et al. (1988) conducted a groundbreaking study of the Deaf Mentor Experimental Project from the SKI-HI Institute (2017) at Utah State University that since 1972 has provided training and services related to home intervention for young children with sensory impairments. The authors reviewed literature and principles regarding bilingual education for deaf children and the higher English literacy achievements of deaf children of signing deaf parents (e.g., Strong & Prinz, 1997) prior to reporting findings from “exploratory research to obtain introductory data on the efficacy of that model” (Watkins et al., 1998: 30).

Watkins et al. compared the learning outcomes from a group of 18 children and their parents in Utah who received deaf mentor home visiting services, and another group of 18 children and their parents in Tennessee who received only spoken or signed English services from a parent adviser. The deaf mentors provided the Utah group with ASL instruction, information about deaf culture, and introductions to the local deaf community as well as ASL-based interactions with deaf children in the home setting. At the start of the study, children in both groups ranged from 27.2 to 28.6 months of age (Watkins et al., 1998). Both groups received hour-long weekly home visits for approximately 18 months. It was reported that children receiving deaf mentor services had significantly greater expressive and receptive language gains, and vocabularies that were more than twice as large as children in the Tennessee group. Moreover, the Utah children scored 2.5 times higher on a test of English grammar than the children in Tennessee. Parents in the Utah group receiving ASL instruction from a deaf mentor reported less frustration when communicating with their children and used more than six times as many signs as parents in Tennessee.

The SKI-HI Deaf Mentor Curriculum (HOPE, 2017) for teaching ASL and deaf culture and supporting young deaf children’s language development through play-based activities continues to be used across the United States and Canada. This curriculum includes 37 ASL lessons aimed at teaching families ASL grammar and communication skills, 18 lessons about early visual communication, and lessons about deaf history and culture (Crace et al., 2016). The ASL lessons focus on teaching elements of ASL grammar and syntax, including facial expression, declarative statements, question types, directional verbs, pronouns, and word order (Crace et al., 2016). Each lesson includes a description of the ASL rule or concept being covered, vocabulary, practice sentences and dialogue, suggested games and activities, and references and resources (Crace et al., 2016). The early visual communication lessons include information about communicating with and responding to young deaf children in ASL. Each Deaf Mentor Home Visit Plan includes a section for interacting with deaf children in ASL, a section for helping families learn ASL, and a section for helping families learn about deaf culture.

As seen in the above, pedagogical practices and programs for supporting parents’ sign language learning are often combined with programs for supporting young deaf children’s language and literacy development (see Snoddon, 2014b for a review of literature related to children’s book sharing with sign language). This is also evident in previous research regarding ASL and early literacy programs for parents and young children, including an action research study of an ASL Parent-Child Mother Goose Program for teaching ASL rhymes and stories to parents (Snoddon, 2012). Similarly, Snoddon (2014b) reported findings from a 10-month study of deaf instructors teaching hearing parents how to read books with their children through ASL. A main finding of both studies was a perceived lack of adequate support for parents’ ASL learning via home visiting instruction that was extraneous to the research studies, and the communication difficulties and frustrations that resulted from this. As Napier et al. (2007) reported, for parents of deaf children there is a pervasive need for extended support for learning sign language beyond the early intervention period when home visiting instruction typically ends.

Current pedagogical practices

This section discusses how theories in parent sign language education are currently translated into practice in relation to the use of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) to teach sign language to parents of deaf children. These pedagogical practices and concepts are further exemplified below.

Using CEFR to teach sign language to parents of deaf children

Related to the plurilingual framework discussed above, in the Netherlands there has been groundbreaking research and pedagogical development in terms of developing a classroom-based parent sign language curriculum aligned with the CEFR for second language learning, teaching, and assessment. The CEFR proclaims plurilingualism as a fundamental principle (Coste, Moore, & Zarate, 2009). The CEFR employs proficiency descriptors, or “I can” statements for assessing learners’ receptive, productive, interactive, and mediation skills. See Figure 20.2 to illustrate the list of learner goals for one parent class in the author’s study.

|

Production |

1. I can produce simple mainly isolated phrases about people and possessions. 2. I can sign simple phrases and sentences about myself. 3. I can ask questions about people (direct). 4. I can answer questions about myself. |

|

Understanding |

1. I can understand everyday expressions when delivered to me clearly, slowly and repeatedly. 2. I can understand questions about myself or other people I know. |

|

Interaction |

1. I can interact in a simple way. 2. I can use basic greetings. 3. I can answer simple questions. 4. I can make an introduction by myself. 5. I can use nonmanual markers to indicate that I did follow what has been expressed. 6. I can use nonmanual markers to indicate that I did not follow what has been expressed. |

Figure 20.2 Student goals: A1 can-do statements (class 2, module 1)

These skills are aligned with scales A1-C2, which involve six levels to describe learners’ language proficiency from basic user (A1-A2) to independent user (B1-B2) to proficient user (C1-C2) (Council of Europe, 2001). In Europe, the development of sign language teaching approaches following the CEFR has focused mainly on interpreter training programs (Sadlier, van den Bogaerde, & Oyserman, 2012). Prosign, or Sign Language for Professional Purposes, is a project sponsored by the European Centre for Modern Languages of the Council of Europe that works to specify CEFR proficiency levels for sign languages in the context of interpreter training (Council of Europe, 2017).

In September 2012, Oyserman and de Geus (2013) began implementation of a CEFR-aligned parent course in Nederlandse Gebarentaal (NGT), or Sign Language of the Netherlands. The first researcher was previously involved in adapting CEFR descriptors to NGT (Sadlier et al., 2012). Oyserman and de Geus’ (2013) pioneering curriculum was rooted in the recognition of systemic deficiencies of the NGT teaching then offered to parents, with a mere 52 hours of NGT instruction provided since 1994 to families with deaf children via a main service agency. Oyserman and de Geus’ (2013) first parent course combined communicative NGT teaching with child-focused pedagogical content and aimed at incorporating 100 hours of learning time through 14 weeks of classroom instruction, homework, and other learning and assessment activities (Snoddon, 2015). Two more courses were subsequently developed following the same format to bring parents to more advanced CEFR proficiency levels (Oyserman & de Geus, 2015), and a fourth course was recently developed.

These courses follow CEFR descriptive categories for selecting themes for individual lesson plans and modules for each course or group of learners. The CEFR divides domains, or “spheres of action or areas of concern” where language is used into the personal, public, occupational, and educational (Council of Europe, 2001: 45). For each of these domains, there are individual themes listed under the descriptive categories of locations, institutions, persons, objects, events, operations, and texts (Council of Europe, 2001). This consideration of domains and descriptive categories in the external context of language use allows sign language teachers to develop curricula that meet parent learners’ needs. For example, lesson plans can be developed in accordance with the “personal” domain and category of “persons” to introduce linguistic goals and vocabulary related to family members and personal acquaintances. In the category of “institutions,” family trees and relationships can be further explored. The CEFR proficiency descriptors enable teachers to set learning goals and develop activities for each lesson and module so parents can practice communicating in sign language and apply what they learn in communicating with their deaf children at home and in other settings.

In 2012, ten parent participants enrolled in the first pilot NGT course. All of these parents had deaf children with cochlear implants aged between 7 and 13. Eight of these parents remained enrolled in the third course (Oyserman & de Geus, 2015). For parents enrolled in the first two pilot NGT courses, Oyserman and de Geus (2013) reported significantly longer sentence utterances, with a mean sentence utterance length increase from 3.76 to 4.61 as parents progressed from the first to the second course. Parents produced significantly fewer lexical errors, with an average decrease from 9.25 to 3.43, and fewer fluency interrupts, with an average decrease from 35.25 to 16.38, representing a 46.5% reduction in fluency breaks, hesitations, and self-corrections (ibid.). Parent participants reported improved communication with their children, fewer experiences of frustration, and better knowledge of sign language following the second parent NGT course (ibid.). Before the first course and during and after each course, parents were assessed following CEFR proficiency descriptors for NGT. From before the first course to the end of the third course, parents progressed from a beginner (A1-A2) to an advanced intermediate (B2) proficiency level (Oyserman & de Geus, 2015). This body of work provides compelling empirical evidence regarding the success of rigorous classroom models of parent sign language teaching following current second or additional language learning theory. Parent NGT courses aligned with the CEFR currently take place across the Netherlands, with funding from insurance companies so classes are offered free of charge to parents (de Geus, M., personal communication, April 4, 2017).

The above pedagogical practices have in common the aim of supporting parents of deaf children’s unique sign language learning needs. However, there is a contrast between practices that support the congregation of parents as a distinct group of learners, as in immersion programs and specialized parent classes, and practices that focus on teaching individual families in the home via deaf mentor services or distance learning. Moreover, programs for supporting parents’ learning are often combined with initiatives for supporting deaf children’s language and literacy development that may reduce the amount of direct sign language instruction provided to parents themselves.

Future trends

This section identifies gaps in current theory regarding how teaching sign language to parents supports deaf children’s development, and the implications for sign language teaching and learning across the lifespan. This section also addresses gaps in practices in terms of developing formal curricula, teaching, teaching materials, research, and school and community collaborations to meet parents’ learning needs. These key areas for future research are outlined below.

Future research studies

There is a body of evidence that suggests that deaf and hard of hearing children need to acquire sign language and engage in elaborated communication with their families and caregivers. As children grow older, their sign language communication needs become increasingly complex. To date, preliminary evidence suggests that best pedagogical practices in parent education include an action-oriented, learner-centered approach in parent sign language teaching with classes and teaching materials that are designed to meet parents’ unique needs in communicating with and raising deaf children, and that are provided on an ongoing basis throughout a deaf childhood until parents reach an advanced level of sign language proficiency. Future parent educators are invited to follow this approach and practices as much as possible, and as much as they are relevant and adaptable across parents’ sign language learning contexts. Sign language teachers need opportunities to engage with L2/Ln learning theories, frameworks, and research that will in turn inform new curricular approaches that meet the needs of the parents.

In Canada, preliminary work has taken place in terms of adapting the Dutch CEFR-aligned parent sign language teaching model to an ASL context (Snoddon, 2015, 2018). This project involved the provision of training workshops facilitated by Dutch collaborators for a small group of Canadian ASL instructors, and the hosting of two pilot parent ASL courses in Toronto and one course in Ottawa (Snoddon, in press). However, challenges have been identified in terms of the need to improve training for Canadian ASL teachers in order to successfully implement a CEFR framework (Snoddon, 2018). These challenges include moving beyond the Signing Naturally curriculum and its communication approach (Smith, Lentz, & Mikos, 2008) that is dominant in many ASL instructional contexts. Moving beyond this approach is needed in order for ASL instructors to learn a new, dynamic theoretical framework for L2/Ln teaching and learning that is flexible and adaptable to diverse learner needs, such as those of parents of deaf children (Snoddon, 2018). These ASL instructor training needs extend to sign language teachers in other contexts around the world who will also benefit from support in theory, curriculum, and teaching materials development. Indeed, the CEFR is in the process of being taken up by sign language teachers across Europe and other international contexts mentioned in this chapter (Council of Europe, 2017). Current and future research initiated by the author includes investigating the alignment of the CEFR-based parent ASL curriculum with the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) proficiency guidelines to merge with the framework employed by ASL teachers in the USA and further promote and expand the parent curriculum.

Future pedagogical practices

The importance of teaching sign language to parents of deaf children has regained prominence in deaf education, along with the need for formal curricula and theoretically grounded, evidence-based practices in teaching parents sign language. However, this area underscores the need for educators of the deaf to collaborate with L2/Ln teachers of sign languages, and for the expansion of training and resources provided to all sign language teachers. Where parents of deaf children are concerned, sign language teachers need information about how to develop and adapt curricular content and lesson plans to meet family communication needs in addition to supporting parents’ achievement of advanced levels of sign language proficiency. Courses developed for parents require sustainable funding to meet communication needs throughout childhood.

As described in this chapter, supporting parents’ sign language learning needs fuels increased advocacy for both bilingual models of education for deaf children and deaf children’s sign language rights. Providing parents with high-quality sign language education requires collaboration between schools, deaf organizations, sign language teacher associations, early intervention service providers, and parents themselves. What deaf communities and sign language teachers can do today is take responsibility to ensure all parents of deaf children have access to learning sign language on a par with other L2/Ln sign language learners.

References

ACTRAC. (1996). Certificate III in Auslan. Melbourne, Australia: Australian National Training Authority.

Coste, D., Moore, D., & Zarate, G. (2009). Plurilingual and Pluricultural Competence. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Strasbourg: Language Policy Unit. Retrieved November 6, 2013 from www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/source/framework_en.pdf

Council of Europe. (2017). Sign Languages and the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Descriptors and Approaches to Assessment. Retrieved January 31, 2017 from www.ecml.at/ECML-Programme/Programme2012-2015/ProSign/tabid/1752/Default.aspx

Crace, J., Pittman, P., Abrams, S., & Gournaris, D. (2016, March 13). Deaf Mentor Program. EHDI Conference Pre-Session, San Diego, CA.

Czubek, T.A. & Snoddon, K. (2016). Bilingualism, philosophy and models of. In G. Gertz & P. Boudreault (eds.), The Deaf Studies Encyclopedia (Vol. I) (pp. 79–82). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

HOPE Inc. (2017). Deaf Mentor Curriculum. Retrieved April 24, 2017 from http://hopepubl.com/proddetail.php?prod=102

Humphries, T., Kushalnagar, P., Mathur, G., Napoli, D.J., Padden, C., Rathmann, C., & Smith, S. (2012). Language acquisition for deaf children: Reducing the harm of zero tolerance to the use of alternative approaches. Harm Reduction Journal, 9, 16.

Humphries, T., Kushalnagar, P., Mathur, G., Napoli, D.J., Padden, C., Rathmann, C., & Smith, S. (2014). Bilingualism: A pearl to overcome certain perils of cochlear implants. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 21 (2), 107–25.

Knoors, H., & Marschark, M. (2012). Language planning for the 21st century: Revisiting bilingual language policy for deaf children. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 17 (3), 291–305.

Komesaroff, L.R., & McLean, M.A. (2006). Being there is not enough: Inclusion is both deaf and hearing. Deafness and Education International, 8 (2), 88–100.

Kushalnagar, P., Mathur, G., Moreland, C.J., Napoli, D.J., Osterling, W., Padden, C., & Rathmann, C. (2010). Infants and children with hearing loss need early language access. Journal of Clinical Ethics, 21 (2), 143–54.

Mahshie, S.N. (1995). Educating Deaf Children Bilingually: With Insights and Applications from Sweden and Denmark. Washington, DC: Pre-College Programs, Gallaudet University.

Mayer, C., & Leigh, G. (2010). The changing context for sign bilingual education programs: Issues in language and the development of literacy. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 13 (2), 175–86.

Mitchell, R., & Karchmer, M. (2004). Chasing the mythical ten percent: Parental hearing status of deaf and hard of hearing learners in the United States. Sign Language Studies, 4 (2), 138–63.

Napier, J., Leigh, G., & Nann, S. (2007). Teaching sign language to hearing parents of deaf children: An action research process. Deafness & Education International, 9 (2), 83‒100.

Nicholson, N., Martin, P., Smith, A., Thomas, S., & Alanazi, A. (2016). Home visiting programs for families of children who are deaf or hard of hearing: A systematic review. Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention, 1 (2), 23–38.

Nilsson, A-L., & Schönström, K. (2014). Swedish Sign Language as a second language: Historical and contemporary perspectives. In D. McKee, R. Rosen, & R. McKee (eds.), Teaching and Learning of Signed Languages: International Perspectives and Practices (pp. 11–34). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2018). Ontario Infant Hearing Program Language Development Service Guidelines. Version 2018.02. Toronto, ON: Ministry of Children and Youth Services.

Oyserman, J., & de Geus, M. (2013). Hearing Parents and the Fluency in Sign Language Communication. Poster presented at the Theoretical Issues in Sign Language Research Conference 11, London, UK.

Oyserman, J., & de Geus, M. (2015). Teaching Sign Language to Parents of Deaf Children. Poster presented at the 2nd International Conference on Sign Language Acquisition, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Peterson, P.R. (2007). Freedom of speech for deaf people. In L. Komesaroff (ed.), Surgical Consent: Bioethics and Cochlear Implantation (pp. 165–73). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Roberts, L. (1998). The Outreach ASL Program (2nd ed.). Belleville, ON: Sir James Whitney School for the Deaf Resource Services.

Sadlier, L., van den Bogaerde, B., & Oyserman, J. (2012). Preliminary collaborative steps in establishing CEFR sign language levels. In D. Tsagari & I. Csépes (eds.), Collaboration in Language Testing and Assessment (pp. 1–19). Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang.

SKI-HI Institute (2017). Home Page. Retrieved April 24, 2017 from www.skihi.org/

Smith, C., Lentz, E.M., & Mikos, K. (2008). Signing Naturally Units 1–6 Teacher’s Curriculum. San Diego, CA: Dawn Sign Press.

Snoddon, K. (2012). American Sign Language and Early Literacy: A Model Parent-child Program. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Snoddon, K. (2014a). Hearing parents as plurilingual learners of ASL. In D. McKee, R. Rosen, & R. McKee (eds.), Teaching and Learning of Signed Languages: International Perspectives and Practices (pp. 175–96). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Snoddon, K. (2014b). Ways of taking from books in ASL book sharing. Sign Language Studies, 14 (3), 338–59.

Snoddon, K. (2015). Using the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages to teach sign language to parents of deaf children. Canadian Modern Language Review, 71 (3), 270–87.

Snoddon, K. (2018). Whose ASL counts? Linguistic prescriptivism and challenges in the context of parent sign language curriculum development. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21 (8), 1004–15.

Snoddon, K. (in press). Teaching sign language in the name of the CEFR: Exploring tensions between plurilingualism and ASL teaching ideologies. In A. Kusters, M. Green, E. Moriarty Harrelson, & K. Snoddon (eds.), Sign Language Ideologies in Practice. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Speech-Language & Audiology Canada. (2014). Over half of Canadian provinces and territories lacking when it comes to newborn hearing screening [News release]. Retrieved April 4, 2017 from www.sac-oac.ca/sites/default/files/resources/Report%20Card%20Reveals%20Provinces%20Lacking%20Newborn%20Hearing%20Screening_SAC-OAC_March%202014.pdf

Strong, M., & Prinz, P. (1997). A study of the relationship between American Sign Language and English literacy. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 2 (1), 37–46.

Svartholm, K. (2010). Bilingual education for deaf children in Sweden. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 13 (2), 159–74.

Svartholm, K. (2014). 35 years of bilingual deaf education—and then? Educar em Revista (spe-2), 33–50.

Takala, M., Kuusela, J., & Takala, E-P. (2000). “A good future for deaf children”: A five-year sign language intervention project. American Annals of the Deaf, 145 (4), 366–74.

Ulfsparre, S.I.E. (1977). Teaching sign language to hearing parents of deaf children. Paper presented at the First National Symposium on Sign Language Research and Teaching, Chicago, IL.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2013). Newborn Hearing Screening. Retrieved April 4, 2017 from https://report.nih.gov/NIHfactsheets/ViewFactSheet.aspx?csid=104

Watkins, S., Pittman, P., & Walden, B. (1998). The deaf mentor experimental project for young children who are deaf and their families. American Annals of the Deaf, 143 (1), 29–35.

Yoshinaga-Itano, C. (2003). From screening to early identification and intervention: Discovering predictors to successful outcomes for children with significant hearing loss. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 8 (1), 11–30.

Young, A.M. (1997). Conceptualizing parents’ sign language use in bilingual early intervention. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 2 (4), 264–76.

Young, A.M. (1999). Hearing parents’ adjustment to a deaf child: The impact of a cultural- linguistic model of deafness. Journal of Social Work Practice, 13, 157–76.