23

The uses of corpora in L1 and L2/Ln sign language pedagogy

Lorraine Leeson, Jordan Fenlon, Johanna Mesch, Carmel Grehan, and Sarah Sheridan

Introduction

Leech and Candlin (1986) remarked that in this current world of information there is a need for “classroom access to language databases, lexicographic, and grammatical corpora” that can be used by language “learners (not only lexicographers and grammarians) [who] can understand” (ibid.: xvi). In this vein, sign language corpora offer the opportunity for the teaching of sign languages in both L1 and L2/Ln classes. The establishment and development of annotated sign language corpora has served as a lynchpin for usage-based descriptions of many sign languages, leading to significant insights into aspects of language form, function, and variation, and, as a result, revisions of many assumptions about aspects of sign language structure (e.g., Börstell, Mesch, & Wallin, 2014; Cormier et al., 2012; de Beuzeville, Johnston, & Schembri, 2009; Fenlon et al., 2015; Fenlon, Schembri, & Cormier, 2018; Fitzgerald, 2014; Johnston et al., 2015; Leeson & Saeed, 2012; Mesch & Wallin, 2012; Mohr, 2014). While these L1 corpora offer unrivaled sources for pedagogical practice, very little has been written about their application in teaching and learning with a small number of exceptions (Cresdee & Johnston, 2014; Leeson, 2008; Mesch & Wallin, 2008).

At the same time, recent decades have seen increased reflection on the application of corpora to spoken language teaching and learning which have yet to be applied to sign language teaching and learning (Aijmer, 2009; Aston, 2001; Campoy, Belles-Fortuo, & Gea-Valor, 2012; Lavid, Hita, & Zamorano-Mansilla, 2012). While L2 corpora are also important sources for exploration of the process of L2 (and indeed, Ln) sign language learning, these corpora have emerged relatively recently (e.g., Mesch & Schönström, 2018; Schönström et al., 2015; Schönström & Mesch, 2014; Sheridan, 2016). The focus of this chapter is primarily concerned with the leveraging of existing sign language corpora in sign language teaching and learning.

Theoretical perspectives

Defining a “corpus”

A linguistic corpus is a collection of texts that is representative, is in machine-readable form, consists of authentic texts, and acts as a standard reference (McEnery and Hardie 2012). For example, the British National Corpus (BNC), a 100 million-word corpus, meets these criteria. It is representative; a broad range of texts from written and spoken sources was sampled for inclusion in the corpus (i.e., portions of these texts were selected and ordered according to explicit linguistic criteria). It is machine-readable; computer-run searches within the corpus determine the frequency and distribution of specific constructions (see BNCweb: http://corpora.lancs.ac.uk/BNCweb/). The BNC contains authentic texts, spoken or written, which serve a communicative purpose (e.g., a newspaper article is written to inform people of news of importance). Finally, the BNC can act as a standard reference; because the corpus is sampled and representative, findings from this corpus can be generalized to the language variety used in the United Kingdom during the early 1990s, when it was established.

Although corpus linguistics methodologies can be traced back to the late nineteenth century, the use of corpora in language research in the twentieth century has not always been popular (see McEnery & Hardie, 2012). Corpus linguistics was criticized for being a poor model of language competence and, particularly before significant technological advances, a labor-intensive industry. Instead, obtaining judgments on language via introspection and elicitation was often considered a more efficient practice. However, corpus linguistics has gradually grown in favor partly due to technological advances in computer software. Today, corpora can be created quickly and annotations can be enriched (e.g., lemmas can be tagged for grammatical category). Linguists can now use corpora to extract information on the frequency of linguistic elements (e.g., how often grammatical patterns occur) as well as the frequency of co-occurrence of these elements (e.g., what words frequently occur together). Such information, which is much more difficult to obtain via introspection, has important implications for different domains of linguistics (e.g., in understanding grammaticalization or language acquisition).

Many contemporary corpus linguists advocate a combination of introspective and corpus-based procedures as best practice in linguistics. Note, however, that most corpora based on spoken languages consist of written texts since they are easy to convert to a machine-readable format quickly. In contrast, spoken corpora are much more time-consuming to produce and therefore not as widely available. For example, in the case of the BNC, spoken language data accounts for just 10% of the entire corpus (www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/corpus/index.xml) while written data accounts for the remaining 90%. Multimodal corpora are rare, as the technology available to annotate them has only recently been made available. Similarly, work on sign language corpora is very much in its infancy.

Why sign language corpora?

Writing about the rationale for establishing sign language corpora, Johnston (2016) notes that a core objective of sign language corpus linguistics “is to empirically ground SL description in usage in order to validate previous research and generate new observations” (ibid.: 5–6). This is particularly important, as research involving sign languages has often been based on elicited datasets from a small number of signers. This approach is difficult to justify when one considers that sign language use is extremely variable. This variation can be partly attributed to the fact that sign languages are young minority languages with few native signers and an interrupted pattern of intergenerational transmission. Therefore, it is often difficult for users (even native signers) to say with a degree of certainty what is and isn’t an acceptable construction in their language. Johnston goes on to note that the documentation of sign languages, via corpus creation, assists in language maintenance and serves to function as a cultural artifact in its own right. Further, and more immediately, he notes that corpora serve “to create teaching and learning materials for SL-using communities because it is often difficult for learners to get adequate exposure to the language” (Johnston, 2016: 5–6; see also Van Herreweghe & Vermeerbergen, 2012).

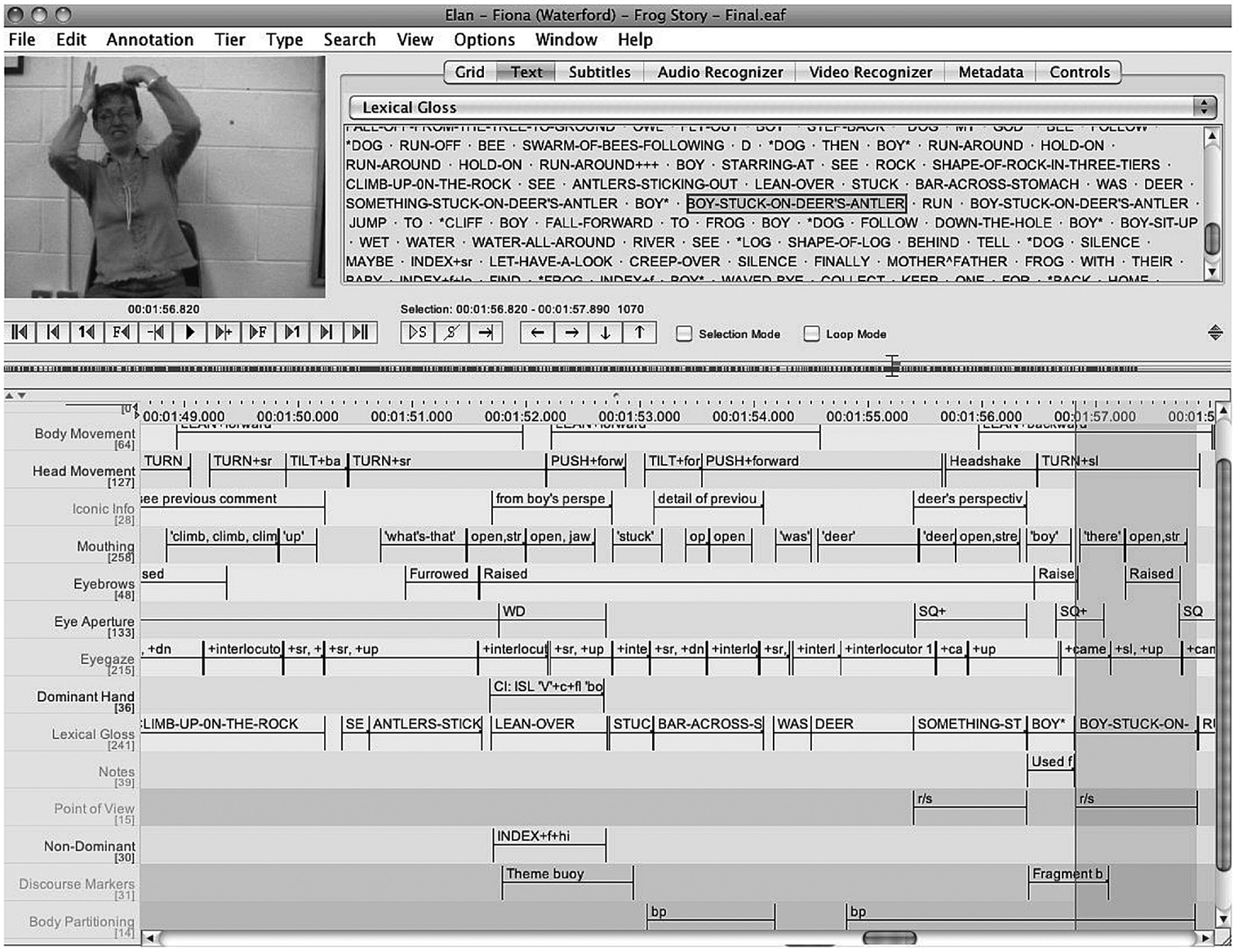

There has been an increase in the number of sign language corpora worldwide in the last decade. Prior to this, few sign language datasets could be subjected to linguistic annotation (e.g., tagged for parts of speech) on a large scale. Although sign language datasets could be converted to written glosses, this approach is problematic since there is no widely agreed-upon writing system for any sign language and the association with the primary data is lost in the conversion process (see Fenlon et al., 2015 for an overview). The development of time-aligned video annotation software, such as ELAN (Wittenburg et al., 2006), together with increased computer capacity for the storage of digital data addressed this major shortcoming and allowed sign language corpora to flourish. Using ELAN, annotations such as sign glosses could be directly associated with a specific interval within a media file. Additional annotations, either offering different levels of linguistic analysis (e.g., phonological or syntactic) or associated with a different articulator (e.g., the brows), could also be associated with the same interval on corresponding tiers. The use of such software and overlapping annotations means that it is possible to search for and quantify the frequency of occurrence of a large range of constructions across multiple files to gain a more accurate picture of sign language use (e.g., the frequency of eyebrow raises with WH-questions by different signers). Note, however (as described below), that the type of searches possible is reliant on the type and amount of annotations that have been carried out to date. In Figure 23.1, a screenshot of ELAN from the Signs of Ireland Corpus is provided.

Figure 23.1Signs of Ireland Corpus. Fiona (36) Frog Story (Waterford)

Corpora in language teaching and learning

Corpora have a well-defined role to play in linguistic research, but they are also valuable in the classroom environment (Johansson, 2009). The use of textual corpora for language teaching purposes is a relatively recent phenomenon (Sinclair, 2004). Sinclair (2004) reports that corpora were not warmly welcomed by either the research community or language teachers. Instead, he says, corpus-driven approaches have only recently received any serious attention from applied linguists, claiming that, “[f]or a quarter of a century, corpus evidence was ignored, spurned and talked out of relevance, until its importance became just too obvious for it to be kept out in the cold” (ibid.: 1). While there has been some shift in this regard, significant gaps remain regarding how corpora can be effectively leveraged in teaching and learning of both spoken and sign languages.

Today, teachers and learners of spoken languages are increasingly likely to make use of corpus-based educational materials including dictionaries and grammars. At the same time,

few teachers are clear about the nature of corpora, or their significance for language teaching, and fewer still have ever made direct use of a corpus. The questions most frequently asked by teachers are: What is a corpus? How are corpora relevant to language teaching? How can they be used?

Gabrielatos, 2005: un-numbered

Part of the challenge relates to the question of how useful corpora might be, a question that has been raised from a number of perspectives in the literature. Gabrielatos (2005) notes that those skeptical of corpora have expressed reservations about their potential to adequately capture language use (e.g., Widdowson, 1991). Others have challenged the usefulness of native-speaker (L1) corpora in providing a model for teaching (Prodromou, 1997); indeed, some have argued that L1 corpora can intimidate learners (Gabbrielli, 1998), or disempower teachers (Dellar, 2003).

Cresdee and Johnston (2014) report that traditionally, information related to language features that appear in textbooks or curriculum guides has frequently been based on writers’ intuition, anecdotal evidence, and traditions (O’Keefe, McCarthy, & Carter, 2007; Reppen, 2010). However, the rise of corpus-based analyses has led to the beginnings of empirically driven descriptions of language use, which facilitate the identification of frequency patterns and allow us to better understand how register-specific discourse shape language use. These, in turn, can either support or challenge assumptions that have been held about the nature of language structure. As a result, frequency studies based on actual language use can lead to pedagogical changes that are beneficial for learners.

At the same time, leveraging corpora in the classroom requires preparation and intervention from language teachers. Teachers have a responsibility to filter corpus data for learners, seeing corpora as offering significant potential for material development rather than being used in their raw form. Teachers can also take advantage of corpora by, for example, exploring frequency information in the target language, by using data sets to compare across registers, and for exploring associations between grammatical structures and words (lexico-grammar). As described below, one of the challenges with applying such principles to sign language teaching and learning contexts is the fact that many corpora are small, not fully annotated, and decisions around labeling phenomena (e.g., grammatical classes) have the potential to influence the way in which phenomena are categorized (Pizzutto & Pietandrea, 2001).

Corpora and sign languages in L1 and L2/Ln

The analysis of a sign language requires video-recorded data as a starting point and a mechanism for annotating and leveraging the dataset. In both sign language research and gesture research communities, ELAN is a tool that has revolutionized the capacity for handling large bodies of data expressed in the visual-gestural modality. It facilitated the development of significant corpora for British Sign Language,1 Australian Sign Language,2 Sign Language of the Netherlands,3 German Sign Language,4 Swedish Sign Language,5 Irish Sign Language, French Sign Language, and French-Belgian Sign Language,6 among others. These corpora consist of lexical items and grammatical constructions that are produced by L1 users of sign languages. While these corpora have been used as a resource for research, they have not been widely leveraged in teaching and learning (Leeson, 2008). Most existing corpora have been annotated only with respect to what a given research project is focused on (e.g., verb type, point of view predication, etc.), which inevitably limits the scope of the searchability function for learner-led corpus engagement. At the same time, Crasborn (2015) suggests that complete phonetic annotation of sign languages is simply not possible. Despite limitations associated with partially annotated corpora for teaching purposes, the wealth of data that emerges from a sign language corpus offers virtual access to a community of signers hitherto impossible to introduce in a classroom setting.

Cresdee and Johnston (2014) discuss how the Auslan corpus can be leveraged in sign language teaching and learning, advising that the first step in corpus-based teaching entails ensuring that information conveyed to instructors and included in curricula is correct. They point out that in both spoken and sign language teaching and learning contexts, decisions that influence curriculum development are influenced by theoretical, empirical and pedagogical assumptions about the nature of language and language teaching and learning. Additionally, native speaker/signer intuitions are not wholly reliable. Cresdee and Johnston (2014) report that native speaker intuitions about typical language choices are often wrong and frequently skewed. They suggest that use of the Auslan corpus (in their context) can assist in identifying authentic patterns of use that can inform teaching. They note that without such data, learners have problems identifying which language features to use in which contexts because intuitions are vague and/or inaccurate. They exemplify this at various levels of the lexico-grammar in Auslan, including: phonology (e.g., handshape or handedness), lexis (e.g., dialect variation or the differences between closely related signs), and grammar (e.g., the grammatical class of some signs). Critically, they argue that Auslan teachers might overgeneralize or oversimplify observations regarding sign language use because their training has not been able to benefit from the findings from naturalistic corpora.

It is critical that individuals who work with sign language curricula ensure that existing claims regarding their use are compatible with findings from these corpora. Furthermore, Cresdee and Johnston (2014) note that the fact that teachers lack the training to search and analyze corpus data in order to supplement their teaching materials only serves to exacerbate the problem. This, then, brings us to consider the pedagogical basis for using corpora in applied ways.

Pedagogical practices

Drawing on corpora offers an opportunity to embed sociotechnical theory into teaching and learning practice. Sociotechnical theory refers to the inter-relatedness of both social and technical aspects in organizations and processes (Trist & Bambford, 1951). Applying this to language teaching, Scharer (2010) reports that the key principles inherent to the theory are: “responsible autonomy, referring to internal group leadership and supervision; whole task responsibility, referring to a minimum of instructions to achieve defined goals; and meaningfulness, as a source of inspiration and motivation” (ibid.: 328). Such principles should be embedded into approaches to using corpora in the sign language classroom. The use of corpora encourages learners to discover patterns and make generalizations about sign language form and use based on observation of usage data, particularly in L2/Ln classrooms (Cresdee & Johnston, 2014; Leeson, 2008).

Inductive approaches, which promote effective learning by discovery and inquiry learning (Felder & Henriques, 1995), are also principles that underlie learner autonomy (Ridley, Ushioda, & Little, 2003). Inductive learning forms part of “data-driven learning” (Johns, 1991, 2002). It is an approach that exploits machine-readable linguistic corpora and creates opportunities for learners to generate generalizations about the target language. Cresdee and Johnston (2014) report that this can be supported in L2 classrooms by introducing structured, focused corpus search activities designed by the teacher, for example, as outlined by Leeson (2008) for Irish Sign Language (ISL). Typically, search results are displayed and manipulated, facilitating the identification of authentic examples of language in use. As Cresdee and Johnston (ibid.: 100) point out, “In this way, both learning and teaching are strongly rooted in authentic language data.”

An overview of current research and (evolving) practice for sign language teaching classrooms is given in the remainder of this section. Note, however, that there is currently very little published data that discusses applied sign linguistics in general (Napier & Leeson, 2016), and the application of sign language corpora in teaching and learning specifically.

Cresdee and Johnston (2014) report four major steps that are required when planning to apply corpus findings in teaching and learning environments. They are:

(1)Foundational work: i.e., consideration of instructors’ knowledge of linguistic and grammatical concepts that underpin the subject matter that is taught.

(2)Intuition versus data checking: awareness of potential mismatch between intuitions and data.

(3)Implementation process: strategies for using the corpus to inform the design of learning activities.

(4)Integration of corpus material into teaching resources: i.e., use of clips of actual usage of the target sign or grammatical construction from the corpus rather than overreliance or exclusive reliance on modeled or invented examples.

Naturally, there are several challenges arising from these recommendations, some inextricably linked to the current status of sign languages. For example, few sign language teachers have a robust understanding of linguistics and are appropriately skilled to leverage corpora. Only two European higher education institutions (Ireland and the Netherlands) offer a pathway to a degree in sign language teaching. In other countries where formal training for sign language teacher training was previously offered (e.g., United Kingdom), it is no longer available. This means that sign language teachers in many countries lack access to formal training as language teachers. Although some opportunities may be available via generic teacher training (see Danielson & Leeson, 2017), the chance for sign language teachers to formally learn about pedagogy, assessment, and corpus linguistics are extremely limited in many countries. This impacts on the rate and quality at which useful tools like corpora are applied in sign language teaching and learning environments, especially outside of higher education institutes pursuing sign language corpus projects themselves.

As Napier and Leeson (2016) point out, approaches to the teaching and learning of sign languages are often under-informed by empirical evidence in the field of applied linguistics generally, and, specifically, do not harness recent findings from sign linguistics. This is partially explained by the lack of formal educational pathways to sign language teacher education in most countries. The problem is that this extends the gap between theory and practice, in this case, sign language teaching practice. However, some work is underway to try to address this gap. These include the European Commission funded project, Sign Teach (see: www.signteach.eu), and the Council of Europe’s European Centre for Modern Languages (ECML) three-year Promoting Excellence in Sign Language Instruction7 project.

Further, since the use of sign language corpora requires proficiency in ELAN, it takes time to develop skill in using this annotation software. Teachers must be comfortable with the software and be able to teach learners how to annotate, if this will form part of their teaching and learning repertoire. This also requires access to adequate computer equipment and the corpus itself. It may be necessary to set aside a period of time each week for learner self-access and/or computer laboratory-based work on corpus issues, and this assumes that local timetabling challenges can be overcome. While timetabling may seem an inconsequential issue, it can be the downfall of many best laid plans given ever increasing demand on limited teaching space and the limited number of qualified personnel working in the field.

With competence using ELAN, and a strong foundation in the linguistics of sign languages, the potential to explore how a corpus can facilitate data checking of intuitions about a given sign language can emerge. Teachers can lead classes in quests to evaluate assumptions about, for example, the distribution of aspectual markers (see Cresdee & Johnston, 2014).

In terms of implementation, there are some excellent examples of good practice that can be highlighted. For example, corpora can be used in a number of ways that promote active learning. These include use of exercises that are developed to explore concordancing patterns, culturally specific discourse elements (sociolinguistic variables that map to gender or age, for example), and exercises used in translation and interpreter educational settings. In the following section, examples from Sweden and Ireland are described.

Using Swedish Sign Language corpus data in classroom

At Stockholm University, Swedish Sign Language (STS) corpus building has been ongoing since 2003 (ECHO project 2003–4; and the Swedish Sign Language Corpus project 2009–11). As of 2018, the STS corpus contains approximately 90,000 sign tokens which are available to learners and teachers. Each of these 90,000 tokens in the STS corpus has also been tagged for parts of speech; additional annotations indicating larger constituents is also available for 10% of the STS corpus. The STS corpora was first developed by the faculty, and then used for teaching purposes. The learners and faculty use ELAN as a tool for searching, analyzing, discussing, and annotating STS not only for research, but also for teaching and learning purposes.

Students take an initial STS course to develop skills in transcribing manual and non-manual forms in accordance with established conventions, including annotations that account for morpho-phonological, syntactical, and textual entries. Students then learn how to use ELAN for searching, analyzing, and annotating entries. A manual containing conventions of corpus notation is given to them. Access to the corpus is through the university website, which is an important consideration for supporting autonomous engagement with the material and independent work with the data outside of the classroom.

To support learners working with the corpus, teachers direct learners towards certain components of the corpus. For example, learners are given a specific sign language phenomenon to search for and/or annotate. A good exercise for beginners working with ELAN is to explore where a sign begins and ends, and whether the signer’s two hands are acting together or separately. Students are also required to look at phonological aspects of a sign (e.g., handshape) and then annotate a small part of the corpus data drawing on established annotation conventions with assistance from the STS dictionary. Students are also asked to select the appropriate gloss for each sign and then justify their decisions in class; this allows for consideration of unique identifiers (ID-glosses) and variants (Johnston, 2010).

In other exercises, learners can be asked to explore the corpus while considering a range of questions (e.g., use of fingerspelling, compounds, depicting signs and the usage, form, and function of signs articulated with one or two hands). Ensuring that teachers do not demand performance that is out of reach of learners is important. For example, beginners may struggle if asked to annotate tiers for non-manual features (e.g., eyebrow, eye gaze, and eye aperture). Instead, learners can be introduced to some pre-annotated files that demonstrate how such features are annotated. For beginners taking STS, for example, conversation analysis forms part of the curriculum, and learners are asked to identify topics, topic changes, instances of turn taking, overlap and back-channeling with reference to the annotated corpus.

Learners who worked with the STS corpus data reported that they gained a deeper understanding of how signed languages differ from spoken languages. They learned about “old signs” and “new signs,” in which they otherwise would not encounter in the classroom. They found that conversational turns for sign languages, and for deafblind signers, are different from conversational turns in spoken languages. Indeed, one learner reported that in group discussions, the corpus showed patterns of overlaps in discourse that were different from what she assumed would hold for sign languages. Learners also reported that they enjoyed the technical challenge of working with ELAN and the annotation system.

Using Irish Sign Language corpus data in classroom

The Signs of Ireland (SOI) corpus is a highly annotated corpus containing some 46,499 tokens (Leeson & Saeed 2012), with tiers marked up for a range of lexical and non-manual information including: eyebrows, eye aperture, lexical gloss, dominant hand, non-dominant hand, mouthing, body movement, head movement, iconic information, point of view. A subset of data set is marked up for discourse markers. Work is currently underway to mark up some of the data for grammatical class.

Leeson (2008) reports on how the corpus is used in the teaching and learning of ISL and associated courses at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland (e.g., sign linguistics, translation, and interpreting modules, ISL modules). ISL courses at Trinity College Dublin are mapped to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2001; Leeson & Byrne-Dunne, 2009; Leeson et al., 2016). The SOI corpus is leveraged when delivering aspects of the curriculum that link with specific thematic domains identified in CEFR, such as life experience, travel, education, and employment. The corpus is also a resource for illustrating use of specific grammatical features to learners in similar ways to those described for STS learners above.

If a corpus is not fully annotated, it may still have the information from which to draw on for examples to illustrate particular features. Corpus data can also be used for sign language receptive skills tests, mapped to CEFR (or similar frameworks), and in evaluation of learner capacity to identify patterns that occur in the sign language of study. Leeson (2008) reports how learners taking an introductory course in sign language linguistics and sociolinguistics were required to identify patterns of occurrence, explore the distribution and frequency of specific sociolinguistic features (e.g., lexical variation), and to draw on the corpus in preparing end of year essays. She describes a range of other ways in which the SOI corpus is used, for example, asking learners to look closely at collocational norms for ISL, and consider the distribution of discourse features and features such as metaphor and idiomatic expression. Students then connect their findings to their reading of the literature and/or to their own or peers’ class presentations. Students are supported in their development as autonomous learners as they work through corpus-search-driven tasks. Leeson reports that this has proven to be an effective mechanism for increasing learner awareness of the range of variability in ISL (lexical items, use of mouthing, size of signing space, etc.), but also in terms of the grammatical features that hold across the language. She also reports that through working with the SOI corpus, learners come to appreciate how change occurs over time in ISL. For instance, they found that older women use mouthings to a greater extent than older men, and young men and women do more mouthing than fingerspelling when compared to older men (Fitzgerald, 2014; Leeson & Saeed, 2012; Mohr, 2014).

Autonomous reflective practice supports learner identification of strengths, weaknesses, and recurring habits (Patrie, 2000; Ridley, Ushioda, & Little, 2003). Thus, learners also have non-class-based opportunities to work with the SOI corpus. Undergraduates are required to take a mandatory research methods module as a component of the Bachelor in Deaf Studies. Students with intermediate skill in ISL (B2- CEFR) worked with Smith (a PhD candidate) to code a subset of the SOI corpus, comprising constructed action (CA) and grammatical class. A task-list was established using Basecamp (Basecamp.com), an online project management tool, and learners received a step-by-step exercise list that included learning how to use ELAN; understanding CA, and grammatical classes; understanding the annotation methodology and tier structure in the corpus; and completing annotate-check-record with changes processes for quality assurance. The learners received face-to-face support from Smith and the Centre for Deaf Studies faculty (deaf and hearing). They prepared a report, which served as their assessment for the module. The learners reported that the project “has not only deepened our knowledge … of the grammatical structures of ISL but … [represents] a unique experience of collaborative work” (Coburn Gray et al., 2018: 2).

Practical considerations in using corpus in pedagogy

Some practical issues arise when considering how to leverage sign language corpora within the sign language classroom. Teachers must set aside time to plan how they will implement corpus-driven activities into their practice and the level of competence of learners must be taken into consideration from the beginning. A teacher must consider the advantage/s of adopting corpus-driven approaches for a particular cohort and consider how they will enhance learners’ attainment of articulated learning outcomes for a course. Once a corpus-driven approach is determined to be useful, exercises that focus on annotation, or linguistic analysis can prove helpful in prompting learner engagement with sign language data in a meaningful way. This also allows for flipped classroom approaches where learners work in their own time and bring their work product to class for discussion and engagement (Barrett, 2012) and Problem-based Learning approaches, where learners are provided with a realistic problem that they solve as part of a structured group process, with teachers serving as coaches and facilitators (Darling-Hammond et al., 2008; Thomas, 2010).

Further, in classes that are teacher-led, groups can engage in corpus searches for examples of particular structures (as described above). The process of mapping a corpus to CEFR (Council of Europe, 2001) or the Standards for Learning American Sign Language (American Sign Language Teachers Association, 2014), or other parallel framework of description is a time-consuming, but worthwhile enterprise as it facilitates subsequent ease in identifying what body of authentic corpus data is ideally targeted at learners at a particular stage of development (e.g., beginner (A-level), intermediate (B-level), advanced (C-level)). Due to a lack of training opportunities, teachers require support in working confidently with ELAN. Corpus project teams for specific sign languages should consider developing a short manual (available in text and sign language) to support sign language teachers (e.g., Mesch, 2011). Furthermore, teachers need to be notified about updates that have arisen regarding changes in annotation conventions applied by a corpus team.

While it is true that sign language corpora are generally still too small to allow for generalizations regarding sign language use, they provide a very good complement to traditional language teaching approaches. For learners of a sign language, working with a corpus allows the opportunity to hypothesize about their target language and test theories via a process of discussion with their peers, and with their teacher/s who can evaluate their progress and function as the learners’ cultural and linguistic guide and local point of reference. The potential learning that arises from peer learning opportunities should not be underestimated (Boud, Cohen, & Sampson, 1999), which, in the case of a sign language learner, typically occur in the target (sign) language.

Future trends

Future research studies

Research findings based on sign language corpora have been published in linguistic journals, and it is crucial that these results are implemented in curriculum design and revision for their respective sign languages. They look at a wide range of linguistic phenomena such as phonological (Fenlon et al., 2013), lexical (Stamp et al., 2014) and morphosyntactic variation (Cormier, Fenlon, & Schembri, 2015; Fenlon, Schembri, & Cormier, 2018). Some provide evidence that may run contrary to popular opinion/expectation. For example, Cormier, Fenlon, & Schembri (2015) illustrate how indicating verbs in BSL (i.e., verbs that move in space to indicate arguments) rarely move from left to right in neutral space to indicate two third person arguments. Instead, signers in the corpus frequently prefer to use constructed action (i.e., they embody an argument of the verb). There may be an overwhelming focus on constructions in some teaching curricula which are rare in sign language discourse. Prioritizing frequent constructions when teaching is not only beneficial to the learner but also ensures that they will understand a wide range of sign language discourse quickly. Going forward, it is therefore important that current research is relayed quickly and clearly to sign language practitioners, and that they can embed that in their practice.

Information on lexical frequency has yet to be leveraged effectively in teaching curricula. Lexical frequency lists are available for Auslan (Johnston, 2012), BSL (Fenlon et al., 2014), and STS (Börstell et al., 2016), and can be used by the teachers to teach the most frequent signs earlier to learners. As with spoken languages, these sign language frequency studies have demonstrated that a small number of signs can account for a large proportion of the text. For example, in BSL, the top 100 signs in the BSL corpus account for 56.6% of the overall dataset. Therefore, prioritizing these 100 signs ensures that a learner can access at least half of the annotated content in the BSL corpus. The lexical frequency list can also be exploited further in the creation of simple, artificial sentences to be taught to learners. Restricting the lexical items used in these sentences to the most frequent items ensures accessibility and further training for the learners (i.e., repeated usage means that these items will become entrenched in a learner’s mental lexicon).

While this chapter has addressed how corpora can be leveraged in teaching and learning settings, an area that is slowly gaining attention from researchers is “Learner Corpora,” a branch of research that is concerned with the language development of L2/Ln learners. Hummel (2013) states that when testing existing theories on second language acquisition and/or creating new hypotheses, researchers are frequently creating and analyzing L2/Ln repositories to legitimize their findings. Therefore, methodologies associated with the development and optimization of learner corpora are garnering increased attention and can assist researchers who are embarking on this journey (Mackey & Gass, 2011).

Future pedagogical applications

We hope to see multi-disciplinary teams comprising corpus linguists, computer scientists, SLA specialists and teaching practitioners collaborating to harmonize corpus building activities and application of the same in teaching and learning settings, with maximum efficacy, ensuring that sign language teachers are a critical part of the process of engaging with, interpreting and mediating linguistic research in teaching and learning environments. This will be crucial in ensuring usability of corpus software by end users (i.e., sign language teachers) and the immediate transferability and impact of research findings on teaching design and practices. There is also a need to examine how learners respond to learning that entails working with sign language corpora.

As outlined above, work with sign language corpora is a promising area for teaching and learning. There are many ways that a corpus can be successfully leveraged pedagogically, though some “translation” of research to practice is required. Importantly, as stated repeatedly in this chapter, how sign language corpora are integrated into sign language teaching depend ultimately on the type and amount of annotations available to learners. Few sign language corpora can be described as fully annotated at the lexical level. Additional annotations (e.g., showing grammatical information for a specific sign or how signs can be grouped together into larger constituents) are also rare. The extent and availability of these annotations determines the kind of activities teachers can set within the sign language classroom. A sign language corpus in its earlier stages with limited annotations available will provide a useful basis for investigating language use as it varies from person to person. In contrast, a sign language corpus that has been annotated extensively will enable more global searches that the learner can base their observations upon. Therefore, improved availability of the type and amount of annotations to learners will subsequently enhance and extend the usefulness of sign language corpora in the classroom and the activities available to them. Note that non-annotated components of sign language corpora can be leveraged effectively in class with careful planning, such as leveraging existing work to guide annotations of a non-annotated component.

Looking forward, we assume that sign language teacher training will be embedded in higher education, with appropriate recognition of sign languages in place in the political and educational sphere. With this as a backdrop, teacher education would entail training in how to leverage sign language corpora effectively in their teaching practice. This would necessarily involve guiding teachers in exercises that have them map the level of competence required by a learner to understand the content of individual movie files, and the threshold competencies required for a learner to be deemed to have moved (or be transitioning) from one level of competence to another. They would also engage in developing corpus-driven activities for learners to conduct searches for use of particular lexical and grammatical categories.

References

Aijmer, K. (ed.) (2009). Corpora and Language Teaching. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

American Sign Language Teachers Association. (2014). Standards for Learning American Sign Language. Gainesville, FL: American Sign Language Teachers Association.

Aston, G. (ed.) (2001). Learning with Corpora. Bologna, Italy: CLUEB.

Barrett, D. (2012). How “flipping” the classroom can improve the traditional lecture. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 12, 1–14.

Basecamp.com. (n.d.). How Basecamp Works, What it’s Like to Organize Your Projects & Teams in One Place. [online] Available at: https://basecamp.com/how-it-works [Accessed February 25, 2018].

Börstell, C., Hörberg, T., & Östling, R. (2016). Distribution and duration of signs and parts of speech in Swedish Sign Language. Sign Language and Linguistics, 19(2), 143–96.

Börstell, C., Mesch, J., & Wallin, L. (2014). Segmenting the Swedish Sign Language Corpus: On the possibilities of using visual cues as a basis for syntactic segmentation. In O. Crasborn, E. Efthimiou, E. Fotinea, T. Hanke, J. Kristoffersen, & J. Mesch (eds.), Proceedings of the 6th Workshop on the Representation and Processing of Sign Languages: Beyond the Manual Channel [Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC)]. (pp. 7–10). Paris: European Language Resources Association (ELRA).

Börstell, C., Wirén, M., Mesch, J., & Gärdenfors, M. (2016). Towards an annotation of syntactic structure in the Swedish Sign Language Corpus. In E. Efthimiou, E. Fotinea, T. Hanke, J. Hochgesang, J. Kristoffersen, & J. Mesch (eds.), Proceedings of the 6th Workshop on the Representation and Processing of Sign Languages: Corpus Mining [Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC)], Portorož, Slovenia, May 28, 2016, (pp. 19–24). Paris: European Language Resources Association (ELRA).

Boud, D., Cohen, R., & Sampson, J. (1999). Peer learning and assessment. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 24(4), 413–26.

Campoy, M.C., Belles-Fortuno, B., & Gea-Valor, M.L. (eds.). (2012). Corpus-based Approaches to English Language Teaching. London: Bloomsbury.

Coburn Gray, C., Flynn, S., Gibney, C., Murray, L., & Rice, E. (2018). Signs of Ireland Annotation Project. Unpublished essay submitted in part-fulfillment of the requirements of the Bachelor in Deaf Studies. Dublin: Centre for Deaf Studies, Trinity College (University of Dublin).

Cormier, K., Fenlon, J., Johnston, T., Rentelis, R., Schembri, A., Rowley, K., & Woll, B. (2012). From corpus to lexical database to online dictionary: Issues in annotation of the BSL Corpus and the development of BSL SignBank. Paper presented at the 5th Workshop on the Representation and Processing of Sign Languages: Interactions between Corpus and Lexicon. Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC) Istanbul, May 2012.

Cormier, K., Fenlon, J., & Schembri, A. (2015). Indicating verbs in British Sign Language favour motivated use of space. Open Linguistics, 1 (1), 684–707.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crasborn, O. (2014). Transcription and notation methods. In E. Orfanidou, B. Woll, & G. Morgan (eds.), Research Methods in Sign Language Studies: A Practical Guide (pp. 74–88). London: Wiley.

Cresdee, D., & Johnston, T. (2014). Using corpus-based research to inform the teaching of Auslan (Australian Sign Language) as a second language. In D. McKee, R.S. Rosen, & R. McKee (eds.), Teaching and Learning of Signed Language: International Perspectives (pp. 85–110). London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Danielson, L., & Leeson, L. (2017). Accessing teacher training and higher education. In K. Reuter, & M. Wheatley (eds.), TBC. Brussels: European Union of the Deaf.

Darling-Hammond, L., Barron, B., Pearson, D. P., Schoenfeld, A.H., Satage, E.K., Zimmerman, T.K., Tilson, J.L. (2008). Powerful Learning: What We Know about Teaching for Understanding. London: Wiley.

de Beuzeville, L., Johnston, T., & Schembri, A. (2009). The use of space with indicating verbs in Australian Sign Language: A corpus based investigation. Sign Language & Linguistics, 12 (1), 53–82.

Dellar, H. (2003). What have corpora ever done for us? Developing Teachers. Retrieved from www.developingteachers.com/articles_tchtraining/corporapf_hugh.htm

Felder, M.R., & Henriques, E.R. (1995). Learning and teaching styles in foreign and second language education. Foreign Language Annals, 28 (1), 21–31.

Fenlon, J., Schembri, A., & Cormier, K. (2018). Modification of indicating verbs in British Sign Language: A corpus-based study. Language, 91 (1), 84–118.

Fenlon, J., Schembri, A., Johnston, T., & Cormier, K. (2015). Documentary and corpus approaches to sign language research. In E. Orfanidou, B. Woll, & G. Morgan (eds.), Research Methods in Sign Language Studies: A Practical Guide (pp. 156–72). London: Wiley.

Fenlon, J., Schembri, A., Rentelis, R., Vinson, D., & Cormier, K. (2014). Using conversational data to determine lexical frequency in British Sign Language: The influence of text type. Lingua. International Review of General Linguistics. Revue Internationale de Linguistique Generale, 143, 187–202.

Fenlon, J., Schembri, A., Rentelis, R., & Cormier, K. (2013). Variation in handshape and orientation in British Sign Language: The case of the ‘1’ hand configuration. Language & Communication, 33 (1), 69–91.

Fitzgerald, A. (2014). A Cognitive Account of Mouthings and Mouth Gestures in Irish Sign Language. PhD dissertation. Trinity College Dublin, Dublin.

Gabbrielli, R. (1998). Incorporating a student corpus in your teaching. IATEFL Newsletter, 141, 14–15.

Gabrielatos, C. (2005). Corpora and language teaching: Just a fling or wedding bells? TESL-EJ, 8 (4), 1–37.

Hummel, K.M. (2013). Introducing Second Language Acquisition: Perspectives and Practices. London: Wiley.

Johansson, S. (2009). Some thoughts on corpora and second-language acquisition. In K. Aijmer (ed.), Corpora and Language Teaching (pp. 33–44). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Johns, T. (1991). Should you be persuaded – Two samples of data driven learning materials. English Language Research Journal, 4, 1–16.

Johns, T. (2002). Data driven learning: The perpetual challenge. In B. Kettermann, & G. Marko (eds.), Language and Computers: Teaching and Learning by Doing Corpus Analysis. Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Teaching and Language Corpora. Graz July 19–24, 2000, (pp. 107–17.). Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi.

Johnston, T. (2010). From archive to corpus: transcription and annotation in the creation of signed language corpora. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 15 (1), 106–31.

Johnston, T. (2012). Lexical frequency in sign languages. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 17 (2), 163–93.

Johnston, T. (2016). Auslan Corpus Annotation Guidelines. Retrieved from www.academia.edu/29690332/Auslan_Corpus_Annotation_Guidelines_November_2016_revision_

Johnston, T., Cresdee, D., Schembri, A., & Woll, B. (2015). FINISH variation and grammaticalization in a signed language: How far down this well trodden pathway is Auslan? Language Variation and Change, 27 (1), 117–55.

Lavid, J., Hita, J.A., & Zamorano-Mansilla, J.R. (2012). Designing and exploiting a small online English-Spanish parallel corpus for language teaching purposes. In M.C. Campoy, B. Belles-Fortuno, & M.L. Gea-Valor (eds.), Corpus-based Approaches to English Language Teaching (pp. 138–48). London: Bloomsbury.

Leech, G., & Candlin, C.N. (1986). Introduction. In G. Leech, & C.N. Candlin (eds.), Computers in English Language Teaching and Research (pp. xi‒xvii). London: Longman.

Leeson, L. (2008). Quantum leap – Leveraging the signs of Ireland Digital Corpus in Irish Sign Language/English interpreter training. The Sign Language Translator and Interpreter, 2 (2), 149–76.

Leeson, L., & Byrne-Dunne, D. (2009). Applying the Common European Reference Framework to the Teaching, Learning and Assessment of Signed Languages. Deliverable D3.1 of project D-Signs, Distance online training in sign language. Leonardo da Vinci Program, EU.

Leeson, L., & Saeed, J. (2012). Irish Sign Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Leeson, L., van den Bogaerde, B., Rathmann, C., & Haug, T. (2016). Sign Languages and the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. Common Reference Level Descriptors. Graz: European Centre for Modern Languages.

Mackey, A., & Gass, S.M. (2011). Research Methods in Second Language Acquisition: A Practical Guide: London: Wiley.

McEnery, T., & Hardie, A. (2012). Corpus Linguistics: Method, Theory, and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mesch, J. (2011). Att använda ELAN: Bruksanvisning för annotering och studie av teckenspråkstexter. Version 3. Avdelningen för teckenspråk, Institutionen för lingvistik. Retrieved from http://su.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?searchId=1&pid=diva2%3A456764&dswid=-5469

Mesch, J. & Schönström, K. (2018). From design and collection to annotation of a learner corpus of sign language. In M. Bono, E. Efthimiou, E. Fotinea, T. Hanke, J. Hochgesang, J. Kristoffersen, J. Mesch, & Y. Osugi (eds.), Proceedings of the 8th Workshop on the Representation and Processing of Sign Languages: Involving the Language Community [Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC)], Miyazaki, Japan, May 12, 2018, (pp. 121–6). Paris: European Language Resources Association (ELRA).

Mesch, J. & Wallin, L. (2008). Use of sign language materials in teaching. In O. Crasborn, E. Efthimiou, T. Hanke, E. Thoutenhofd, & I. Zwitserlood (eds.), Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on the Representation and Processing of Sign Languages: Construction and Exploitation of Sign Language Corpora [Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC)]. (pp. 134–7). Paris: European Language Resources Association (ELRA).

Mohr, S. (2014). Mouth Actions in Sign Languages: An Empirical Study of Irish Sign Language. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton and Ishara Press.

Napier, J., & Leeson, L. (2016). Sign Language in Action. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

O’Keefe, A., McCarthy, M., & Carter, R. (2007). From Corpus to Classroom: Language Use and Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Patrie, C.J. (2000). Cognitive Processing Skills in English. San Diego, CA: Dawn Sign Press.

Pizzutto, E., & Pietandrea, P. (2001). The notation of signed texts. Sign Language and Linguistics, 4 (1/2), 29–45.

Prodromou, L. (1997). Corpora: The real thing? English Teaching Professional, 5, 2–6.

Reppen, R. (2010). Using Corpora in the Language Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ridley, J., Ushioda, E., & Little, D. (2003). Learner Autonomy in the Foreign Language Classroom: Teacher, Learner, Curriculum and Assessment. Dublin: Authentik.

Scharer, R. (2010). The European Language Portfolio: Goals, boundaries and timelines. In B. O’ Rourke & L. Carson (eds.), Language Learner Autonomy: Policy, Curriculum, Classroom. A festschrift in Honor of David Little (pp. 327–36). Bern: Peter Lang.

Schönström, K., Dye, M., Leeson, L., & Mesch, J. (2015). Building up L2 corpora in different signed languages – ASL, ISL and SSL Poster presentation at International Conference on Sign Language Acquisition, Amsterdam, July 1–3, 2015.

Schönström, K., & Mesch, J. (2014). Use of nonmanuals by adult L2 signers in Swedish Sign Language – Annotating the nonmanuals. In O. Crasborn, E. Efthimiou, E. Fotinea, T. Hanke, J. Hochgesang, J. Kristoffersen, & J. Mesch (eds.), Beyond the Manual Channel. Proceedings of the 6th Workshop on the Representation and Processing of Sign Languages [Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC)] (pp. 153–6). Paris: European Language Resources Association (ELRA).

Sheridan, S. (2016). The Role of Learner Corpora in Language Teaching. Unpublished manuscript, Centre for Language and Communication Studies, Trinity College Dublin.

Sinclair, J. (2004). How to Use Corpora in Language Teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Stamp, R., Schembri, A., Fenlon, J., Rentelis, R., Woll, B., & Cormier, K. (2014). Lexical variation and change in British Sign Language. PLoS ONE, 9 (4), e94053.

Thomas, J.W. (2010). A Review of Research on Project-based Learning. Retrieved from www.bobpearlman.org/BestPractices/PBL_Research.pdf

Trist, E.L., & Bambford, K.W. (1951). Some social and psychological consequences of the longwall method of coal-getting. Human Relations, 4 (1), 3–38.

Van Herreweghe, M., & Vermeerbergen, M. (2012). Data Collection. In R. Pfau, M. Steinbach, & B. Woll (eds.), Sign Language: An International Handbook, (pp. 1023–45). Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Widdowson, H.G. (1991). The description and prescription of language. In J. Alatis (ed.), Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics 1991 (pp. 11–24.). Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Wittenburg, P., Bruman, H., Russel, A., Klassmann, A., & Sloetjes, H. (2006). ELAN: A professional framework for multimodality research. In Proceedings of LREC 2006, Fifth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation.