1 Welcome

Where did you love to play as a child? Maybe it was a tree near your home. A video game where you battled your way through new worlds. Or, like me, a fort you built out of boxes and blankets.

I’ve been talking about playgrounds a lot lately. I’ve been sliding on a lot of slides and trying out a lot of swings. I’ve listened to people talk about why they came to play and wondered who wasn’t able to join in. All this may seem odd for an adult who designs technology for a living, but here’s why it matters: Designing for inclusion starts with recognizing exclusion.

A playground is a perfect microcosm for learning how to start. Think back to the objects and people that occupied your play space. Try to remember what worked well for you. It’s likely there were moments when you were happy to play alone and other moments when you played together with many children. Can you describe what it was that made those spaces inclusive?

It’s also likely there were moments when you felt left out, either because there was an object that you couldn’t use, or because you were ostracized by the people around you. What was it that made these spaces exclusionary?

The objects and people around us influence our ability to participate. Not just when playing on a playground, but in all aspects of society. Our cities, workplaces, technologies, even our interactions with each other are touchpoints for accessing the world around us.

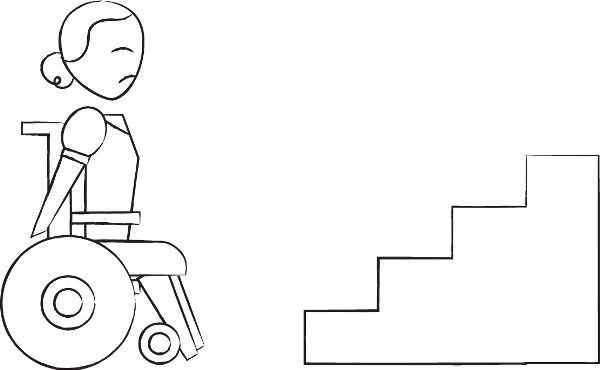

When we meet those access points, sometimes we can interact with them easily and sometimes we can’t. When we can’t interact with ease, many of us will try to adapt ourselves to make the interaction work. There are also times when no degree of creativity will make it possible to use a solution that simply doesn’t fit a person’s body or mind.

Examples of this are all around us. It’s the reason why a child climbs onto a counter to wash their hands at a sink. It’s why people are left searching for instructions on how to navigate a software application when it’s updated with new features. Anyone who’s tried to order lunch off a menu that’s written in a language they don’t understand is in the middle of a mismatched interaction.

This is the power of mismatches. They make aspects of society accessible to some people, but not all people.

Mismatches are barriers to interacting with the world around us. They are a byproduct of how our world is designed.

Mismatches are the building blocks of exclusion. They can feel like little moments of exasperation when a technology product doesn’t work the way we think it should. Or they can feel like running into a locked door marked with a big sign that says “keep out.” Both hurt.

In this book we’ll take a deep dive into how inclusion can be a source of innovation and growth, especially for digital technologies. It can be a catalyst for creativity and an economic imperative. And we’ll contend with a central challenge: is it even possible to design for all human diversity?

Human-to-human interactions are full of mismatches, but people are able to adapt themselves in an effort to connect with each other.

I’ve built a career promoting inclusion through design methods, also known as inclusive design. Like many people, I initially took inclusion at face value as a good thing. Yet I also found that people rarely made it a consistent priority. I wanted to understand why.

There are many challenges that stand in the way of inclusion, the sneakiest of which are sympathy and pity. Treating inclusion as a benevolent mission increases the separation between people. Believing that it should prevail simply because it’s the right thing to do is the fastest way to undermine its progress. To its own detriment, inclusion is often categorized as a feel-good activity.

With this in mind, we will test our assumptions about inclusion and how it shows up in the world around us. We’ll explore the reasons why our society perpetuates exclusion and new principles for shifting that cycle toward inclusive growth.

Misfits by Design

What happens when a designed object rejects us? A door that won’t open. A transit system that won’t service our neighborhood. A computer mouse that doesn’t work for people who are left-handed. A touchscreen payment system at a grocery store that only works for people who read English phrases, have 20/20 vision, and use a credit card.

When we’re excluded by these designs, how does it shape our sense of belonging in the world? This question led me from playgrounds to computer systems, from Detroit public housing to virtual gaming worlds.

Ask a hundred people what inclusion means and you’ll get a hundred different answers. Ask them what it means to be excluded and the answer will be uniformly clear: It’s when you’re left out.

Imagine children climbing on a playground. How are they climbing? Are they on a ladder, stairs, ramps, ropes, boulders, or maybe a tree? Now imagine who designs the features of that playground and the assumptions they make about the people who will play in it. As you might expect, many playground designers are extraordinary advocates for inclusive spaces.

One cloudy San Francisco morning, while we were interviewing Susan Goltsman, she led our team through a park that she designed, pointing out the features that make it inclusive. A gently sloping ramp that reaches the highest lookout points. A harmoniously ringing gamelan, an Indonesian instrument on which “you can’t play a bad tune.”

A frenzy of children of various ages and abilities play together throughout the park. Their shouting and laughter are hard to compete with. With her feet in the sand, next to a giant sculpture of a sea turtle, Susan revealed the most important aspect of her design process:

We interviewed kids with varying levels of disability, and the more severe the disability, the more vicarious the play. So the child who could not move very much was playing full-on in their brain, using other kids out on that play area to play through. So access means a lot of different things to a lot of different people.

Goltsman was a founding principal of the design firm Moore, Iacofano, Goltsman (MIG). Her influence extended far beyond childhood play spaces. One of the early pioneers in inclusive design, her contributions to policy and standards have influenced many major North American cities.1

An inclusive environment is far more than the shape of its doors, chairs, and rampways. It also considers the psychological and emotional impact on people. In partnering with Goltsman I learned that what’s true for a playground is true for all human habitats, including the online world.

From a young age, we test the waters of acceptance by asking “can I play?” The response to this question can make our hearts soar or crush us. Over our lives we learn how to ask more subtly or we simply stop asking. Sometimes we push forward, regardless of rejection, to prove ourselves.

Core elements of our identities are formed by our encounters with inclusion and exclusion. We decide where we belong and where we’re outsiders. It shapes our sense of value and what we believe we can contribute. Exclusion, and the social rejection that often accompanies it, are universal human experiences. We all know how it feels when we don’t fit in.

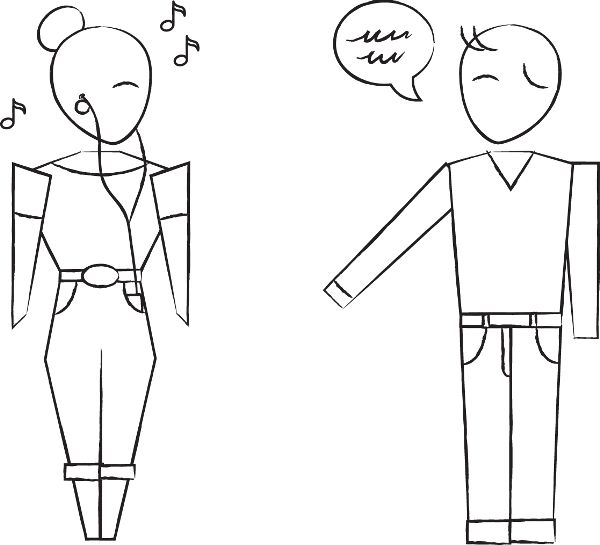

Mismatches between people and objects, physical or digital, happen when the object doesn’t fit a person’s needs. People often have to adapt themselves to make an object work.

For better or worse, the people who design the touchpoints of society determine who can participate and who’s left out. Often unwittingly. A cycle of exclusion permeates our society. It hinders economic growth and undermines business success. It harms our collective and individual well-being. Design shapes our ability to access, participate in, and contribute to the world.

If design is the source of mismatches and exclusion, can it also be the remedy? Yes. But it takes work.

We must broaden our definition of design and designers. We must test our assumptions about human beings. We must wonder “who am I excluding?” and allow the answers to change our solutions.

Above all, we must be willing to acknowledge how much we don’t know about inclusion. No one is an expert in inclusion in all areas of life. We are naturally better at exclusion, for reasons that we’ll explore in the coming chapters. Knowing this, we can find better ways to forge ahead.

Fears and Opportunities

There is a growing interest in making inclusion a positive goal for companies, teams, and products. The first actions for reaching that goal can be the most challenging. As with any expertise, inclusion is a skill that’s developed with practice over time.

Where in life do we learn inclusive skills? In my education as an engineer, designer, and citizen I never formally learned about inclusion or exclusion. Accessibility, sociology, and civil rights weren’t required curricula for learning how to build technology.

As I grew in my career as a technologist, I noticed a void of information on how to practice inclusive design for digital technologies. Most examples of universal design applied to sidewalk curb cuts and kitchen utensils. It was unclear how to achieve similar outcomes in the design of digital technology. In search of guidance, I realized that many people had the same question: where do I start?

Today, my answer to this question is always the same. There are many misconceptions about inclusion. It’s important to know what you’re getting into. These three fears of inclusion will likely strike you at some point. If so, you’re not alone. But from each of them grows an insight into the nature of inclusion.

1. Inclusion isn’t nice

One of the most common fears related to inclusion is a fear of using the wrong words. Many leaders would rather avoid the topic than look bad or offend someone. There isn’t a robust lexicon for inclusion. There are many different interpretations of the word “inclusion,” but very little guidance on what exactly this word means.

As a result, it can be easy to mistake nice words for good intentions. A person or company that offers the right language might not take meaningful action. It can also be easy to chastise someone who is committed to inclusion but who uses the wrong words. There’s a strange irony when a group of people who are passionate about inclusion ostracize a person for saying the wrong thing. This is common across different languages and cultures.

That said, people sometimes say hateful things—and fully mean it. These words can reflect their true motivations. Often, they can be aimed at hurting groups of people who already experience the greatest amount of exclusion. This dangerous behavior is not addressed in this book. Instead, we will focus on the types of exclusion that emerge from being new to the topic and from unchecked exclusionary habits.

Inclusion isn’t nice. It’s challenging the status quo and fighting for hard-won victories. The opportunity is to be clear and rigorously improve our lexicon for inclusion. We can work on clarifying what we mean and why we care. We can create better resources through education and awareness. Asking questions, and then simply listening, is often the most courageous way to start.

Words hold a power to facilitate or freeze progress toward inclusion. Without a shared language, teams struggle to produce tangible results. The topic can often become emotionally charged if personal biases and pain dominate the conversation. Building a better vocabulary for inclusion starts with improving on the limited one that exists today. Sometimes we will use words that hurt people. What matters most is what we do next.

2. Inclusion is imperfect

The second fear is of getting it wrong. And you likely will, at first. You’ll likely never achieve a perfectly universal solution that works for everyone in every situation. A common concern of designers is being forced to create a lowest-common-denominator design. Trying to please everyone is good for no one.

The underlying challenge is the vast complexity of human diversity. There are endless nuances and considerations when designing for people. There is no single answer that suits everyone. Accessible solutions are always, inevitably, accessible to some but not all people. A bathroom stall designed for a person who uses a wheelchair is often inaccessible to someone who stands three and a half feet tall.

Inclusion is imperfect and requires humility. It’s an opportunity to be curious and approach challenges with a desire to learn. It teaches us new ways to adapt our solutions to what people need, which is sometimes different from how a designer thought their solution would work. In this book we’ll look for unifying threads to guide us as we design for human diversity.

3. Inclusion is ongoing

The third fear is scarcity. There are rarely enough talented people, time, and money to make a sudden sea change in inclusivity. Urgency, especially in growth-led businesses, is a constant pressure. The tradeoffs are never easy.

As a result, the work of inclusion is never done. It’s like caring for your teeth. There is no finish line. No matter how well you clean your teeth today, over time they require more care. With inclusion, each time we create a new solution it requires careful attention in its initial design and maintenance over time.

This underscores the beauty of constraints. We can learn how to choose great design constraints, ones that incorporate perspectives we haven’t yet considered. It’s a skill that we can sustain indefinitely if we build it into how we work, embedded into the entire process of creating solutions.

Inclusion is ongoing and in search of a better vocabulary. By association, so is this book. In writing it, I had to constantly remind myself that no one has all the answers. As a reader, I invite you to remember this as well.

In fact, I have a sneaking suspicion that it might not be possible to definitively design this elusive thing we call inclusion. Exclusion, conversely, is recognizable. It’s measurable and tangible. When someone is excluded they know it unequivocally. The experience has an emotional and functional impact on them.

Perhaps, instead, all we can do is recognize and remedy the mismatched interactions in our world. The concrete nature of exclusion gives us something we can deconstruct. With our fears and imperfections in tow, exclusion is where we’ll start.

Why You, Why Now?

This book isn’t an argument that everyone should be inclusive all the time. It’s a case for why we should take responsibility for inclusion as a matter intentional choice, rather than risking an unintentional harm. Can we understand the exclusion created by our solutions before we release them into the world, and design something better?

Exclusion isn’t inherently bad, nor inclusion inherently good. But in a society that sets goals such as a constitutional promise of equal rights and opportunity, barriers to that equality are problematic. For groups with capitalistic motivations, exclusion hinders business growth. A mismatch haunts any designer or technologist who aims to create great solutions but realizes just how much people struggle to successfully use their design.

These factors are amplified by the digital age. Technologies are permeating our public and private spaces. The modern marketer, engineer, or designer is expected to build solutions that reach millions if not billions of people. At that scale, one small exclusionary misstep can have an amplifying negative effect. Conversely, one small change toward inclusion can benefit many people in a positive way.

With respect to business justifications for inclusive design, there are four key categories that we’ll explore in the stories ahead, with a review of each one in chapter 8:

- ■ Customer engagement and contribution,

- ■ Growing a larger customer base,

- ■ Innovation and differentiation,

- ■ Avoiding the high cost of retrofitting inclusion.

There are also concrete social benefits to inclusion. Each time we remedy a mismatched interaction, we open an opportunity for more people to contribute to society in meaningful ways. This, in turn, changes who can participate in building our world.

Designing for human diversity might be the key to our collective future. It’s going to take a great diversity of talent, working together, to address the challenges we face in the 21st century: climate change, urbanization, mass migration, increased longevity and aging populations, early childhood development, social isolation, education, and caring for the most vulnerable among us in an ever-widening gap of economic disparity. You never know where, or who, a great solution will come from.

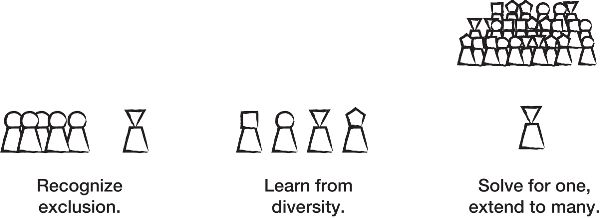

Already there are inclusive solutions quietly at work in our world. They are the early examples by which to measure inclusive outcomes. Their features, and the people who created them, share common threads which are captured here as three inclusive design principles. These will reappear in the coming chapters.

- ■ Recognize exclusion. Exclusion happens when we solve problems using our own biases.

- ■ Learn from human diversity. Human beings are the real experts in adapting to diversity.

- ■ Solve for one, extend to many. Focus on what’s universally important to all humans.

These principles are derived from partnerships with inclusive design leaders, a heritage of successful innovations, and thousands of hours of applying them to product development. To include is a verb. In turn, these principles are also action-oriented.

In business and technology, we commonly look to leaders for guidance on how to be successful in new areas of expertise. I’m often asked for names of companies that are leading examples of inclusion. It’s debatable whether any company is leading, yet. Many are talking about it, most are still early in their journey toward improvement. When it comes to inclusion, companies, and their leaders, have a lot to learn from a very specific kind of leader. It’s not the prominent executive at a high-profile company. Not the faces that grace the covers of industry magazines. Not the people with the highest social media following.

We have the most to learn from leaders who’ve experienced great degrees of exclusion in their own lives.

Their expertise in exclusion means they can acutely recognize it in the world. It fuels their talent as problem solvers. This book follows leaders who are turning this expertise into action through design. They don’t have all the answers, but they are finding better problems to solve. They are working through it, trying new angles, and navigating new paths that will benefit all of us.

With this in mind I’ve chosen specific stories of pioneers whose work on inclusion stems from their own exclusion. When they, and many more leaders with similar expertise, fill the ranks of the most visible positions in society, we’ll know that all of us were good students of their work. Until then, I encourage you to seek out the excluded leaders in your community.

Often I meet new people, stories, and tools dedicated to advancing inclusion. I collect these at www.mismatch.design. These resources are a living companion to this book. I look forward to sharing them with you and evolving them with your input.

Whatever your reason for choosing this book, thank you for reading. Your contributions to building a more inclusive world will reach farther than you can imagine. You will find new ways to recognize and resolve mismatches in the world around you. In turn, you might be surprised by who shows up to play.

Welcome.

■ ■ ■

Takeaways: Mismatches Make Us Misfits

- ■ Inclusion is about challenging the status quo and fighting for hard-won victories.

- ■ People’s touchpoints with each other and with society are full of mismatched interactions. Design is a source of these mismatches, and can also be a remedy.

- ■ Inclusion is ongoing, imperfect, and not nice.

- ■ Exclusion isn’t inherently negative, but it should at least be an intentional choice rather than an accidental harm.