4 Inclusive Designers

John R. Porter’s bedroom would make any die-hard gamer feel right at home. Among the personal computers, beyond the Run Lola Run movie poster, across from a MakerBot busily extruding plastic threads into an unidentifiable widget, is a large black pegboard. The kind of board my grandfather used for hanging hammers and wrenches in his garage.

Mounted on the pegboard, like hunting trophies, are dozens of video game controllers dating back decades. Among them is the 1977 nostalgia-inducing Atari Video Computer System controller, with its joystick and single red button. Hundreds of millions of people used this kind of controller to play the legendary game Pong. Next in line is the 1985 iconic block-shaped Nintendo Entertainment System controller with two buttons and a T-shaped directional pad that players used to maneuver through Super Mario Bros, one of the most popular video games of all time.

Symbiotically, video games and their controllers grew more complex in the 1990s as home video games grew in popularity. Porter’s pegboard features the contoured dual grips of the 1994 Sony PlayStation gamepad and a few hefty Microsoft Xbox controllers released since 2001, adorned with buttons, sticks, triggers, and a directional pad.

Early designs for Atari, Nintendo, Sony’s PlayStation, and Microsoft’s Xbox game controllers.

Moving along what Porter calls his Wall of Exclusion, it’s easy to notice how the controllers grew larger, heavier, and more complex over time. But one thing unites them all. They all require two hands to play.

These controllers are gateways to vast virtual worlds. In these worlds players achieve new skills, explore complex landscapes, and connect with each other. For many years, Porter admired these games from a distance, excluded from playing them by the shape of the controllers.

We first met when Porter was a design intern at Microsoft. He was working on his PhD while teaching at the University of Washington’s Human Centered Design and Engineering program.

Better than most people, Porter can tell you exactly how to create an inclusive solution. Technology is very tightly integrated with everything he does. He uses a wheelchair to get around and assistive technologies to extend his own abilities. These technologies help Porter bridge the mismatched designs that he encounters when using everyday objects and spaces.

In a world where most technology is designed to be used with a keyboard, mouse, or touchscreen, Porter depends primarily on speech recognition. He uses his voice to interact with computers through a software program called Dragon, created by Nuance Communications, Inc. Dragon listens and follows his commands. By talking naturally to his computers Porter can create lesson plans, compose written communications, and participate in online gaming.

He’s active in a community of gamers with disabilities that share elaborate techniques for how to hack together alternate ways to play their favorite games. Sometimes this is a hardware hack, like a switch controller that can be modified to work through head movement. And sometimes it’s a software hack, like programming a sequence of game actions into one simple command. For example, just by saying “prepare for attack,” a program can coordinate multiple characters to aim in the same direction at once, rather than having to align each one manually.

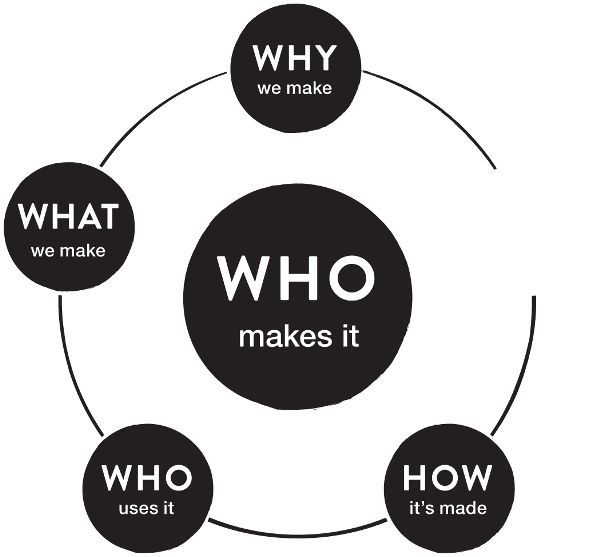

Porter ties his experience with gaming to everyday life, making insightful connections between play and inclusion. Here are some excerpts from a conversation with Porter to guide our exploration of the second element in the cycle of exclusion: who makes it.

Why did you build a Wall of Exclusion?

I keep these here to remind me of all the assumptions that we, as designers, make about people. The design of these products clearly signals that gaming is for some people, and not for others. A game controller says “This is for you” or “This is not for you.” This is true for everything we design.

The people who make solutions hold a power to determine who is and who isn’t able to participate.

What happens when designers make assumptions about people?

All of these games are based on a broad assumption that you’ll be using your fingers and your hands to interact. And for me that is almost entirely moot. I have some physical mobility that I can use to move my wheelchair, but everything I do in the digital realm is mediated through other avenues of interaction, primarily speech.

Whenever I’m using technology I use speech to control it even though it was never designed to work for speech. It’s not just that a game isn’t optimized for my abilities. It was made without ever even considering the possibility that someone would need to interact with it in the ways that I do.

That places the onus on me to figure out all these workarounds. For gamers with disabilities, we have to spend as much time figuring out how to play a game as we do actually playing.

How does a designer make something inclusive?

Games that only allow a user to play in one way, that have a very prescriptive notion of who a player is, those tend to be the ones that are the least accessible. But games that allow more freedom and flexibility tend to be a lot more inclusive.

I often like to point out World of Warcraft as one of the really great inclusive games. There are players who don’t have the motor ability to interact fast enough to engage in combat. But I know people with disabilities who have played this game for years. They have all of their crafting skills maxed out because for them, the game isn’t about doing quests.

The game is economics.

The game is building a leather-working empire and making gear that people can buy from them. And I don’t know if anyone at Blizzard Entertainment would say that they envisioned that as a viable play style. But nevertheless, they built an inclusive system.

What’s the role of gaming in your life?

I still remember the day that my uncle Mike came over to give me Final Fantasy VII as a 12th birthday present. It was my favorite game, despite the fact that I’d never played it. I’d watched him play it, but was never able to join in. I was able to play games until I lost the ability to use game controllers around the age of 10. For me, gaming was becoming a spectator sport.

My uncle once spent an entire afternoon trying to tape little pieces of wood onto his controller to make it work for me. When the efforts were unsuccessful, I told him not to worry about it. Final Fantasy just wasn’t for me. “Sure it is,” he reassured me as he picked up the modified controller, “we just need to stop this thing from getting in the way.”

I don’t just play. I work to figure out how to play. It’s figuring out how to participate in societal moments. Which is a burden sometimes. I think of it as a metagame that I play in all areas of my life. It’s a puzzle to be solved and shared.

How is gaming shifting from exclusion to inclusion?

There is a natural inclination to use yourself as a shortcut to make assumptions about the people that you’re designing for. And I think that’s especially rampant in the world of game design.

Historically, the industry has been incredibly homogenous. Games have been created by people who feel like they are never going to be different than they are in that moment. Many of them feel like they are the only users who really need to be considered. And that’s changing, which is good.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the increasing diversity amongst game designers is happening concurrently with the release of more inclusive games. I think those two things go together.

Porter also points out that for decades, games and consoles were made exclusively by large companies with massive technology requirements that took years to release. Only an elite group of designers worked for these companies.

Today, a growing community of gamers with disabilities, and organizations like AbleGamers, are pushing the creative boundaries of how people design and access games. Years of patience and sheer resourcefulness are opening up the benefits of gaming to a much wider audience.

Also, with multiple open ways to make and publish games, a more diverse group of people are creating more diverse content for people to play. A new generation of inclusive-minded designers and enthusiasts is gradually transforming the gaming industry.

Inclusive designers can emerge from traditional design disciplines. They also come from unexpected backgrounds. It’s important to define the specific design skills that contribute to inclusion, so that more people can become practitioners. This is also why we must reimagine what it means to be a designer.

Deciding Who Designs

The power of shifting who makes has had a similar effect in industries beyond gaming. More designers are focused on how to adapt objects to make them work for a diversity of people. Open-source tools enable more people to contribute to the design of everything from education to artificial intelligence. The cycle of exclusion shifts toward inclusion when more people can openly participate as designers.

Anyone who has ever solved a problem is, in a certain sense, a designer. The only real difference comes in how much ownership you take over the identity of yourself as a designer. You might be a designer if you say that it’s not enough to design for yourself and you want to design experiences for other people too.

Consider the rigid ways that companies hire new employees. Many companies require candidates to complete an online application, an often-tedious process that requires specific language competencies, access to the Internet, and an ability to focus on detailed information for long periods of time.

In the tech industry, a common approach to interviews is for a candidate to meet sequentially with multiple people in a face-to-face verbal interview. The questions are designed to assess how likely a person would be to be successful in the role they’re applying for. As the day wears on, a candidate needs to have a high degree of physical and mental stamina to endure the process.

In the end, the hiring process itself can send a clear signal that the job is “for you” or “not for you.” Yet how many aspects of this process have a direct correlation to how well a person will really perform in a role over a multiyear career?

With this in mind, let’s take a closer look at three skills of successful inclusive designers:

- 1. Identify ability biases and mismatched interactions between people and world.

- 2. Create a diversity of ways to participate in an experience.

- 3. Design for interdependence and bring complementary skills together.

Ability Biases and Mismatched Interactions

Many organizations create solutions for thousands if not millions of people. Creating solutions at such a large scale means hundreds, maybe thousands, of designers and engineers are working together on various aspects of a solution. When all those team members bring their own biases to the process, it can be challenging to make a solution that works well for all the people it is intended for. In fact, it can seem absolutely impossible.

The underlying challenge is human diversity.

A common starting point for teams is to focus on increasing the demographic diversity of their team members. Representation of diversity is important. However, changing representation doesn’t necessarily change culture. Culture change can be hard and takes time. If we increase diversity of a team but don’t also evolve the cultural elements that surround that team, it can place an extra burden on people to navigate the “metagame” of exclusion in their work environment while also delivering successful solutions for the business.

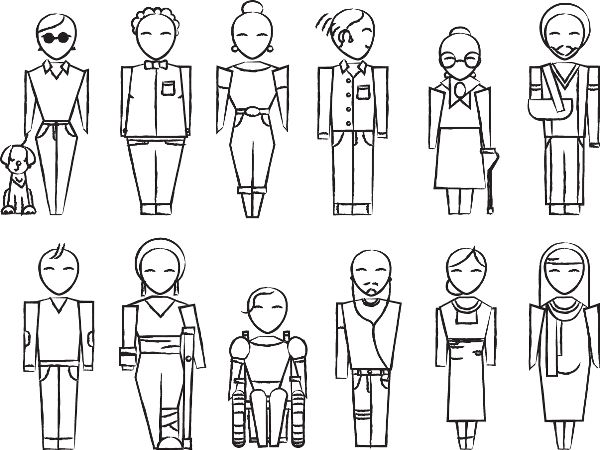

Ability is one of the few categories that transcends all other types of human diversity.

We are all born and gain abilities as we grow. We lose those abilities as we age. As we move through life, our abilities change as a result of illness or injury. They even change when we move from one environment to the next. Our vision changes when we move from a dark movie theater into the bright sunlight. Our ability to hear a conversation changes from a quiet elevator to a crowded party.

Human ability, in its many physical, cognitive, and societal forms, is a building block of design. A person’s capabilities and limitations are always a factor in how successfully they interact with a solution.

Furthermore, something extraordinary happens when we make human ability our first consideration. Everyone can relate to the idea that abilities are limited and ever-changing. It rings true regardless of nationality, professional training, unconscious biases, or worldview. It enables a common ground from which to start designing inclusive solutions.

Of all the biases that designers bring to their work, ability biases are the sneakiest.

Designing with our own abilities as a baseline can lead to solutions that work well for people with similar abilities, but can end up excluding many more people.

An ability bias is a tendency to solve problems while using our own abilities as a baseline. When we do so, our solutions end up working well for people with similar abilities and circumstances, but can exclude a much wider group of people.

Even the most empathetic designer will typically create a solution that she herself can see, hear, and touch. She’ll use her own logic and preferred ways of communicating. Her eyesight acuity, hand dexterity, and language fluency will influence the way she creates solutions. Even the design tools that she uses to create a solution will reinforce her ability biases.

Ability biases aren’t inherently bad. They aren’t necessarily something to eliminate. In fact, they can be strengths. Once a designer develops the skill to recognize their own ability biases, they can start to recognize the ability biases in other people as well.

Porter’s ability biases as a gamer are speech commanding, strategic coordination, and navigating problems through experimentation. But he doesn’t simply design solutions that work for his own abilities. As an inclusive designer, he creates solutions that consider a range of abilities beyond his own, so that a wider audience can successfully use his designs.

How do we extend beyond our own ability biases? No degree of wearing a blindfold will ever be equivalent to the experience of being blind. The blindfold can actually give designers a false sense of empathy, especially if they attempt to simulate disabilities without ever meeting or working alongside people with disabilities.

If we are designing a solution that will be used by millions of people, and our ability biases are inevitable, where do we start?

To unlock this conundrum, I invite you to consider diversity through the lens of human interactions. That is, our interactions with each other and with the world around us.

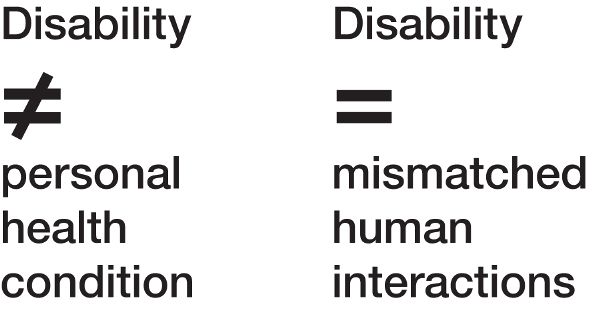

In 2011 the World Health Organization published their World Report on Disability, referring to disability as “a complex phenomenon, reflecting the interaction between features of a person’s body and features of the society in which they live.”1 This is also known as the social definition of disability. These points of interaction are where mismatches occur.

For designers, this can open a new mindset. It’s a profound shift from thinking about disability as a personal health condition outside of the range of “normal.” When we consider disability as a mismatched interaction, it underscores the responsibilities of the designer. Every choice we make either increases or decreases the mismatches between people and the world around them.

When we think about disability in terms of mismatched interactions, it highlights the responsibilities of people who make solutions.

A well-loved example of mismatched design that led to innovation is OXO tools. Betsy Farber was having difficulty using kitchen utensils due to arthritis in her hands. The thin metal handles of objects, like a potato peeler, were difficult and painful to hold. Her husband, Sam Farber, worked with her to develop a new grip design. The new design was rounded to fill the hand and was made of flexible rubber that could shape to the unique grip of each user. The Farbers created their first set of fifteen OXO Good Grips kitchen tools in 1990.

The design was dramatically more comfortable for Betsy, but also worked well for anyone who had difficulty holding kitchen utensils due to wet or slippery hands.

A Diversity of Ways to Participate

Mismatched interactions also arise when we create solutions with only one way to participate. In our gaming example, this can be a controller that requires two thumbs, a high degree of manual dexterity, or a high degree of hand strength. It’s also about the range of roles that players can act out in a game (warrior, merchant, coach, athlete, etc.).

Inclusive designers create a multitude of ways for people to participate in and contribute to an experience.

To better understand this, let’s take a closer look at several definitions of inclusive design. Although the term has been around for decades, it was largely an academic practice until recently. When I first learned about inclusive design, very few companies were applying it to their work in a repeatable way. At Microsoft, we sought out mentors from universities. Most importantly, Jutta Treviranus and her team at Ontario College of Art and Design. Treviranus founded the Inclusive Design Research Centre in 1993 to focus on ways that digital technology can improve societal inclusion. She has a clear approach to selecting each new cohort of designers:

We need designers who have experienced barriers. What we want to produce is not a uniform set of individuals with specific competencies, but a group of individuals that can work as a team, that each can contribute a diverse perspective.2

Another mentor in our early days was the inclusive design leader that I referenced in the opening of this book, Susan Goltsman. Her definition of inclusive design will always be my favorite:

Inclusive design doesn’t mean you’re designing one thing for all people. You’re designing a diversity of ways to participate so that everyone has a sense of belonging.3

Goltsman led her design projects with what she called the I-N-G’s. She would sit and observe how many different human activities were happening in a park. Goltsman would ask, “what I-N-G is most important to this environment?” Maybe it was running, digging, swinging, climbing, or sleeping. Whatever the I-N-G, the next question was always “how many ways can human beings engage in that activity?”

Imagine a playground full of only one kind of swing. A swing that requires you to be a certain height with two arms and two legs. The only people who will come to play are people who match this design, because the design welcomes them and no one else.

And yet there are many different ways you can design an experience of swinging. You can adjust the shape and size of the seat. You can keep a person stationary and swing the environment around them. Participation doesn’t require a particular design. But a particular design can prohibit participation.

The same phenomenon applies to technology. If writing stories required a keyboard, computer screen, and fluency in English, the only stories we’d read would be from people who match these requirements. Each feature created by designers determines who can interact with an environment and who is left out.

Building on Treviranus’s and Goltsman’s guidance, here’s a working definition of inclusive design that we developed at Microsoft, after applying it with thousands of engineers, designers, and business leaders.

Inclusive design: A methodology that enables and draws on the full range of human diversity. Most importantly, this means including and learning from people with a range of perspectives.4

We also found it helpful to distinguish inclusive design from related concepts, like accessibility and universal design. Here’s a quick primer that guided our work:

Accessibility: 1. The qualities that make an experience open to all. 2. A professional discipline aimed at achieving No. 1.

An important distinction is that accessibility is an attribute, while inclusive design is a method. While practicing inclusive design should make a product more accessible, it’s not a process for meeting all accessibility standards. Ideally, accessibility and inclusive design work together to make experiences that are not only compliant with standards, but truly usable and open to all.

Most accessibility criteria grew out of policies and laws that were designed to ensure barrier-free access for specific disability communities. Wheelchair access in architecture only became prominent across the United States after the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed by Congress in 1990. The 1998 Section 508 amendment to the United States Workforce Rehabilitation Act of 1973 mandated that all electronic and information technology be accessible to people with disabilities. The United Nations created a Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2006, as an international agreement to focus on the full societal integration of people with disabilities.5

Inclusive design should always start with a solid understanding of accessibility fundamentals. Accessibility criteria are the foundation of integrity for any inclusive solution.

Another concept that is closely related to inclusive design is universal design.

Universal Design: The design of an environment so that it might be accessed and used in the widest possible range of situations without the need for adaptation.6

Universal design was born out of the built environment. It is rooted in architecture and environmental design. It emphasizes the end solution, most often one that is physically fixed. The principles of universal design are focused on attributes of the end result, such as “simple and intuitive to use” and “perceptible information.”7

In contrast, inclusive design was born out of digital technologies in the 1970s and 80s, like captioning for people who are deaf and audio recorded books for blind communities. Inclusive design is now growing into adulthood alongside the Internet.

In some areas of the world, the term inclusive design is used interchangeably with the term universal design. I prefer to make a distinction between them in two ways.

First, universal design is strongest at describing the qualities of a final design. It is exceptionally good at describing the nature of physical objects. Inclusive design, conversely, focuses on how a designer arrived at that design. Did their process include the contributions of excluded communities?

The second distinction, initially coined by Treviranus: Universal design is one-size-fits-all. Inclusive design is one-size-fits-one. We’ll explore this further in chapter 7 with a technique called a persona spectrum.

Inclusive design might not lead to universal designs. Universal designs might not involve the participation of excluded communities. Accessible solutions aren’t always designed to consider human diversity or emotional qualities like beauty or dignity. They simply need to provide access.

Inclusive design, accessibility, and universal design are important for different reasons and have different strengths. Designers should be familiar with all three.8

An inclusive designer is someone, arguably anyone, who recognizes and remedies mismatched interactions between people and their world. They seek out the expertise of people who navigate exclusionary designs. The expertise of excluded communities gives insight into a diversity of ways to participate in an experience.

Making Accessibility Accessible

If you aren’t already familiar with the basics of accessibility for your field, you’re not alone. The good news is you don’t need to become an expert in solving everything. You just need to know enough to know when you need to bring in a true expert. You need to know how to recognize accessibility issues and how to design solutions that work well with the assistive technologies that people rely on. Here are four unique challenges that people commonly face when they’re new to accessibility.

- ■ Lack of educational resources. Accessibility fundamentals are rarely taught in school or by employers. The companies that are leading in inclusion are creating curricula to help engineers and designers learn the basics. There’s a community of accessibility specialists who are also producing great educational content. Much of this information is available online in open formats, for free. This will give a general introduction to what you need to know.

- ■ Complex legal verbiage. Accessibility focuses on legal standards. The language of these standards can be intimidating, unless you’re a lawyer. Some companies hire external agencies to conduct conformance testing for accessibility standards. Accessibility criteria can also be inexact. That is, they might not give specific details on how to create an accessible solution or measure whether it’s successful.

- ■ Finding the signal in the noise. It can take significant investment and time to build a custom set of criteria that apply to your business or solution. You can also create your own checklist of top exclusion issues to avoid and test for throughout your design process. In general, we need better ways to validate that inclusive solutions are working as intended in the real world.

- ■ A highly manual process. After decades of being underprioritized, the tools for checking accessibility haven’t kept pace with advances in technology. As a result, a lot of product testing is conducted line by line, by human beings. This seems to be changing quickly as more people are building the requirements of accessibility right into development tools. Ideally it would be difficult, if not impossible, to produce an inaccessible product.9

Interdependence and Complementary Skills

In cultures that overemphasize independence, it’s less common to design solutions with interdependence in mind. In the United States, there’s a deep attachment to the idea of a rugged, lone pioneer (or astronaut, or entrepreneur, or cowboy) venturing out into the great unknown to make their way in the world. When they succeed they’re hailed as self-made heroes of strength, ingenuity, and resourcefulness. These stories of independence rarely reflect the truth of our lives, which are full of dependencies.

People with disabilities often depend on human assistants and assistive objects. The skills of these assistants are vital to closing the gaps between the implements of daily life and a person’s abilities. And all people are increasingly dependent on technology to engage with the world.

Interdependence is about matching complementary skills and mutual contributions. Thinking back to Porter’s example of online gaming, vast worlds are inherently more inclusive when they have a diversity of ways to contribute to the game. These games, like any society, don’t thrive solely on the skills of hunters and warriors. The society is a system of interdependent skills, an economy that includes many different types of novices and masters.

When designing a solution, it’s easy to treat people as individual entities. Even in the design of shared products, especially in social media, many solutions assume that groups of people behave merely as collections of independent individuals. Each person is treated as a separate entity, blasting bits of information out to other individual people and waiting to count the number of likes that they receive in return.

An inclusive designer thinks in terms of interdependent systems. They study human relationships. They observe the ways that people bring their skills together to complement each other. Inclusive designers seek out a diversity of ways that people build collective accomplishments.

As inclusive designers, interdependence challenges us to think in broader ways about systems of contribution. It prompts us to ask what human activities, which I-N-G’s, are most important to the things that we design. Designing for interdependence changes who can contribute to a society, what they contribute, and how they make that contribution.

We Are All Designers

The traditional design professions are rapidly changing, especially in areas of technology where the required skills change so quickly that many universities are struggling to maintain a relevant curriculum. Much of today’s design work isn’t limited to people with the word “design” in their professional titles. Among those evolving design roles there is a new category of skills in inclusive design.

This is critical in many areas of society, but urgently needed in technology design. As technology permeates intimate areas of our lives, design becomes an intimate act. People invite products into their homes. They share their secrets with personal devices. They use digital technology to facilitate moments of sharing, celebration, and mourning. Each of these technologies is built by people who are making assumptions based on their own biases. For better or for worse, these choices can also determine who gets to participate in society.

People who’ve experienced great degrees of exclusion can translate that expertise to the solutions they create. Their experience can shape every other aspect of the cycle of exclusion. But this strength isn’t the result of being considered “different” from other designers by some facet of demographic diversity.

Their expertise stems from being familiar with exclusion and what makes it a universal human experience. This knowledge can make it easier to recognize the exclusion that many more people face, bringing a greater appreciation of what is gained when a design process is truly open to diverse perspectives. This is how inclusive designers learn to flex their ideas and combine their strengths.

■ ■ ■

Takeaways: Building the Skills to Recognize and Resolve Mismatches

Exclusion habits

How to shift toward inclusion

- ■ Consider diversity in terms of human interactions and how people change over time.

- ■ Identify ability biases and mismatched interactions that are related to your solution.

- ■ Create a diversity of ways to participate in an experience.

- ■ Design for interdependence and bring complementary skills together.

- ■ Build a basic literacy in accessibility, and grow a depth of expertise in the specific accessibility criteria that are relevant to your solutions.

- ■ Adopt a more flexible definition of a designer. Open up our processes and invite contributions from people with relevant but nontraditional skills.