5 With and For

The next time you’re at a street corner, waiting to cross, take a moment to notice the details of its design. Note the orientation of buildings, the intensity of sounds or crowds of people. Who designed that street corner? How are their choices influencing your ability to move? Or to interact with other people?

Of the many professionals who contribute to the design of our world, architects have to achieve some of the most stringent criteria before being allowed to practice. The degree of training and testing required to become a licensed architect is incredibly high. After completing the necessary education, the credentialing process requires years of experience and thousands of dollars to complete. The whole process can take 12.5 years, on average.1

With public safety at stake, this makes sense. In contrast to the industry of video games, where open-source platforms are making it easier for anyone to become a game designer, it’s hard to imagine the same thing happening in architecture.

Cultural context and preexisting methods can perpetuate the cycle of exclusion.

This makes the role of an architect a useful lens to examine how we make. There’s a greater context, beyond the individual designer, that influences exclusion and inclusion.

In addition to business criteria and technical requirements, a design is shaped by the history of events that precede it. This means that shifting a cycle of exclusion toward inclusion isn’t simply a matter of designing an object in new ways. We also need to disrupt the momentum of how things have been done for a long, long time.

A City of Design

The whirring of power saws and high-pitched beeping of construction trucks fill the downtown streets of Detroit. The skeletons of new high-rises stand tall alongside historic buildings with some of the most beautiful examples of art deco in the country.

In 2015, Detroit became the first U.S. city to be named a UNESCO City of Design. The distinction is an acknowledgment of the city’s rich architectural heritage and a long list of influential local architects and designers who defined American Modern design.2 While Detroit is well known as the heart of the American automotive industry, its artistic strengths are equally impressive.

In my first visit, Tiffany Brown guided me through the city. An architectural designer and native Detroiter, Brown is exceptionally talented at building connections with people. We wove in and out of parks, restaurants, and cathedral-like lobbies of office buildings. She moved at a breakneck pace, sharing vivid details about each location. The nuances of each design and the names of the architects were all new to me.

Brown describes the features of architecture through the stories of the people who gather there to celebrate, mourn, create, and build. The best restaurants for birthday parties. The murals in a quiet alleyway that transforms into a concert venue on weekends. She has a keen sense of how spaces bring people together and how design creates a sense of belonging.

A growing number of architects, like Brown, believe the people who inhabit a space should contribute directly to its design. Her firsthand experience with how design can fail communities motivated her to pursue architecture. She understands how designing for, not with, people can lead to exclusion.

We pass through a small triangular park with the words “Paradise Valley” engraved on the ground. Brown points out vacant storefronts that once formed a thriving economic center for hundreds of Black business owners. People gathered in these streets to hear jazz legends like Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, and Louis Armstrong. This park marks the north end of what used to be Black Bottom, named for its rich marsh topsoil, one of the few neighborhoods where African Americans were allowed to live in the 1920s through the 1950s.

In the early 1900s Detroit was a beacon of economic opportunity, especially for African Americans. The city’s population exploded from less than 500,000 in 1910 to over 1.5 million people in 1930.3 Many of these new residents were African American migrants from the south.4 Neighborhoods like Black Bottom were places whose inhabitants knew and looked out for each other. Residents intermingled with national heroes, like boxer Joe Lewis, and there was a palpable belief in the community that anyone could be great.

Over the course of the decline of the local automotive industry, the nationwide recession in 2008, and the city declaring bankruptcy in 2013, more than one million people left Detroit, likely never to return.

Urban planning and architecture played a role in this decline. Black Bottom was demolished in the early 1960s to make way for the Chrysler Freeway and a new mixed-income neighborhood designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The thriving center of Detroit’s African American community was destroyed and most Black Bottom residents moved to public housing projects across the city.

Brown drives us to the edge of what once was the Brewster-Douglass housing projects. The pace of construction is dramatically softer. The pounding of a hammer starts and stops from inside a brick shell of a partially demolished home. Across the street is a common sight in Detroit: a large lot, empty and overgrown, surrounded by a wire fence with a bright white sign reading “road closed.”

The Brewster Homes, which later grew to become Brewster-Douglass, was the first federally funded housing project in the United States. It was opened with a ceremony attended by Eleanor Roosevelt in 1935. The Brewster Homes promised to be family-oriented residences for working-class African Americans who, at the time, had limited housing options. These first homes were largely funded by private benefactors. For several decades, these homes were well managed and maintained by the federal government.

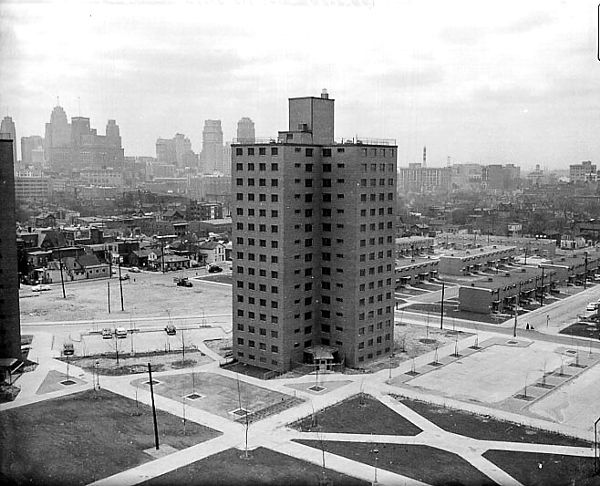

The promise of family-oriented housing started to change when the Frederick Douglass towers were added to the Brewster Homes in 1951. The stark, cramped design of these twenty-story block-shaped towers was a far cry from the original town homes.

A Douglass tower standing next to the original Brewster Homes in Detroit.

This style was typical of the rising modernist movement in architecture that borrowed heavily from a vision set by Swiss-French architect Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris, known as Le Corbusier. His concept of “towers in the park” was just one example of his mathematically precise approach to architecture, based on béton brut—French for raw concrete.

Le Corbusier’s approach to architecture made a strong impression on Robert Moses, a man known as the “master builder” of New York City in the mid-twentieth century. He was also demonstrably racist, as detailed in Robert Caro’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, The Power Broker. Moses built extensive parks, beaches, roadways, tunnels, and bridges that transformed New York City during the decades of his tenure as an appointed public official. And he did so with a keen focus on excluding communities that he deemed unworthy to enjoy them. In one infamous example, he lowered the height of overpasses to prevent the passage of public buses, the primary mode of transit for low-income and African American residents.

One of the practices that Moses embraced, in the footsteps of Le Corbusier, was to demolish what he deemed “blighted” areas, displacing over half a million residents in pursuit of his vision. He would raze entire neighborhoods to the ground, creating a blank slate for new housing projects and expressways. This top-down approach to planning architecture became a beacon of modern urban development, and was replicated in cities across the United States.

Through the 1950s and 1960s Congress allocated fewer and fewer funds to building and maintaining high-quality public housing. As they did, the design quality declined. High-rise towers, often with one elevator to service scores of families, became a design standard for public housing projects across the United States.

With reduced funding, restrictive policies, and neglected maintenance, the buildings of Brewster-Douglass fell into disrepair in the late 20th century. Once home to nearly 10,000 Detroiters, they were marked for demolition, with the promise of rebuilding people’s lives on a foundation of entrepreneurship and training for new jobs.

The last residents were moved out in 2008. Federally funded Section 8 housing vouchers were the only way that many people could afford to live outside of the development, which meant moving into private landlord-owned homes in disparate areas of the city. Many residents protested. Some refused to leave their homes and were forcibly removed.

This story isn’t unique to Brewster-Douglass. The pattern of destroying Black and low-income neighborhoods to make way for “urban renewal” projects has been repeated across Detroit for decades. As the city’s design evolved, it gained new features that excluded people from each other and from economic opportunities.

A racial distribution map underscores this point. Today, the population of Detroit is roughly 700,000 and over 80% are African American.5 The surrounding metropolitan and suburban areas are predominantly Caucasian. The spaces between communities are marked by clear physical boundaries that correspond to major roadways.

The final stages of the Brewster-Douglass demolition were supervised by Brown in 2014 while she was working for the architecture firm Hamilton Anderson Associates. During the project she met with former residents who arrived to watch as buildings were being deconstructed. They shared family stories, remembered loved ones lost, and recalled the places where lifelong friendships took root. People gathered to recognize this place that shaped their lives in profound ways.

Racial distribution in Detroit is sharply segregated along roadways and waterways (shown in white). The population of the areas shown in gray is over 80% African American, and closely follows the boundaries of the city of Detroit. The population of surrounding metropolitan and suburban areas, shown in black, is over 80% Caucasian American. (Based on data from the 2010 U.S. Census.)

The Brewster-Douglass demolition held special meaning for Brown because the complex shared a lot of traits with her childhood home, Herman Gardens, several miles away. As we drove along the edge of the now empty multi-acre lot, she pointed out her schools and the home her family was relocated to when Herman Gardens was demolished.

These important spaces from Brown’s life now stand vacant and deteriorating. These places influenced her choice to pursue architecture. Not out of passion for the buildings, but for the countless neglected residents that they represent.

Many displaced residents, including Brown’s grandmother, returned to live in a small cluster of new homes at the edge of the former Herman Gardens site. From her front porch, we watch her grandchildren climb atop a playground while she recounts the city’s promises of new economic development that never materialized.

She can vividly recall the original community and each space where people gathered. Once the homes were destroyed, the local schools lost students and were closed. Businesses lost customers and ceased to exist. She can describe in detail which aspects of Herman Gardens’ design worked and which didn’t.

Brewster-Douglass was built for low-income African American families. But who created the design? Who chose what to tear down and what to rebuild? What was their cultural agenda? Its construction and deconstruction happened without any meaningful inclusion of residents. This practice isn’t isolated to architecture. It happens in many areas of design, including digital environments.

When we break from the past, how we get to the next stage has an impact on who can move forward with that progress and who’s left out. What does it take to shift long-standing cycles of exclusion?

400 Forward

From her years as a young resident in public housing to her career as an architectural designer, Brown has encountered many layers of designs that contribute to exclusion. And as she works toward her architecture license, there’s one number she always keeps in mind: 400.

In the history of the profession, just over 450 architects have been African American women. In 2017 there were approximately 110,000 licensed architects in the United States. Just over 400 of these active practitioners, roughly 0.3%, are African American women.

The City College of New York conducted a comprehensive study of inclusion in architecture and concluded that the extremely low percentage of African Americans in the profession, just 2% across genders, is the result of specific inequalities in the process of becoming an architect and the support received once new architects are in role. Improving inclusion in the profession, they state, requires deeper study of the “considerations of how minority youth are socialized to think about the field of architecture, and an understanding of the influence of social/peer networks, family guidance, and educational awareness.”6

The credential process is not the only way to describe the profession. There are countless African American builders and architects who have shaped the American landscape. But credentialing matters, because critical decisions about the future of our cities are often made from positions of seniority and power. And these leadership positions are heavily gated by required credentials.

Brown works with young people as a way to shift the future ranks of leadership. She co-founded the Urban Arts Collective, an organization that uses art, music, and interactive workshops to introduce minority students to architecture and design. Her most recent initiative, 400 Forward, is aimed at empowering the next 400 African American female architects.

Here’s how she describes that journey.

How did you choose architecture?

Growing up in Detroit’s inner city, we didn’t have doctors, lawyers, and engineers running to our schools for career day. We had little access to the arts and zero exposure to architecture. Something like architecture surely felt out of reach for us. I was a student at what was considered a failing public school, and a college recruiter came to an assembly when I was in 12th grade. That fall, I was studying architecture. It changed my life, and also changed my outlook on life.

Returning to my old neighborhood to construct new housing was one of many full circle moments for me. Many of my family members still live there, many of my friends. I’ve been asked if I would change the way I grew up. My answer is always no. It is a place where I gained friendships that started from kindergarten and last to this day. My parents’ generation can say the same thing. To some, it was one of the most dangerous places in the city. To us, it was the only community we knew and called home.

I was once convinced the term “disadvantaged youth” was a proper title for young people deemed unable to achieve success because of their environment or social class. That they were less likely to have, let alone achieve, their goals.

I remember being referred to as a disadvantaged youth by educators, if and when they did come to my school. I did not like how it made me feel. I once believed there were certain things beyond my reach because of my upbringing, because I’m female, and because of my skin color. But then I realized this term did not define me. I began to see it as the reason I would prove them all wrong. I am a “disadvantaged youth” who now has three college degrees, two in architecture.

How does a designer shape inclusion?

I would sum it up with a Latin expression, “Nihil de nobis, sine nobis” or “Nothing about us, without us,” which was made prominent by the disability rights movement. This phrase personifies the idea of designing with a community: that no course of action should be decided without total contribution from the people affected by that course of action. Especially groups of people who have been socially excluded, categorized by disability or cultural heritage.

This expression has largely been disregarded in relation to design. As an example, I recently rode the new Q-Line transit system in Detroit. The design of this service emphasizes electronic forms of payment. When it first opened, none of the kiosks offered instructions on how to pay with cash, a secondary option that was only available inside a train. This alienated people in the city who must use change or cash. As a result, it became a way to transport a certain class of people from midtown to downtown and bypass those excluded people. It rides alongside the city bus, stopping at the same traffic lights, held up in the same traffic.

I have personally experienced the outcomes of designing for a particular demographic. The results can be oppressive and unjust. Inhabitants are made to feel powerless and dependent.

What’s your approach to inclusion?

While studying architecture, I realized I learn in ways that are different from many of my peers. I did fine in high school, but had a hard time adjusting to college. There was a disconnect between my thought process and how coursework was presented to me. A lot of students with similar upbringings run into this issue and might think that design is not for them.

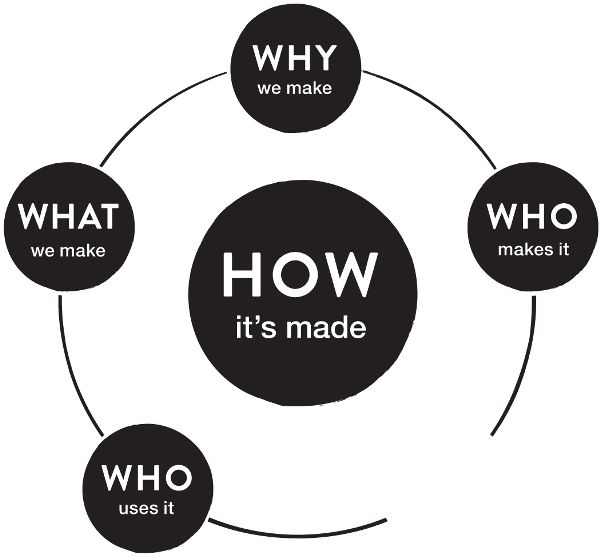

I need to take the time to get to the root of a problem before I can try solving it. I have to see the big picture and how things flow together. Making sense of how things are related to each other helps me make it personally meaningful.

I also find meaningful connections by meeting with people who are going to be affected by the design.

My passion is to create an entirely new leadership base for architecture so that the profession reflects the communities we serve. Diversity paired with passionate creativity improves the quality of life. It should outweigh this “superhero” approach to design that we have today.

How do you make design accessible?

There was a student who was struggling in one of our architecture workshops. The task was to create a city block, using Lego pieces. She didn’t have a logic behind why she’d laid out her city block in a particular way. As designers we try to have some kind of reason for what we did and some kind concept that we start with. Rather than jumping to a design and then rationalizing why we did it. You get to a design because something led you there.

I asked her to think back to something that was emotional for her. She had placed a lot of stores along the front of the city. She explained that shopping was something she did with her mom when she was alive.

I knew right then that she had an emotional story to tell. We talked as she created this block filled with things that she liked to do with her mom. She didn’t have to understand design thinking. She just needed to take a step back and clarify the reason why she was making certain choices. Why is this needed? Why is this important?

I want to make architecture and design feel reachable for kids in neighborhoods like the ones I grew up in. This includes them engaging with someone who’s from the same type of neighborhood. Someone who has defeated the same odds they face and became successful.

When she describes inclusion, Brown focuses on the greater context. The historical moments that led to an existing design. The orientation between designers and users. The leaders who initiate wide-sweeping changes. Above all, her lens highlights the key to making inclusive solutions: including the expertise of excluded communities.

When people are excluded by mismatched designs, they grow intimately familiar with the nature of the exclusion and how it might be resolved. Given the opportunity, they can apply this expertise toward building inclusive solutions.

The next chapter demonstrates how someone who understands the mismatch can resolve it in creative ways. And how this differs from a person who tries to make a solution based on stereotypes or benevolent pity for someone they perceive as unlike themselves.

■ ■ ■

Takeaways: How Generations of Exclusion Are Made and Broken

Exclusion habits

- ■ Creating mismatched interactions and obstacles to leadership positions that influence design decisions. In particular, barriers that aren’t directly correlated to the skills of the profession, such as financial requirements, rigorous scheduling, or only offering one format of test to gain credentials.

How to shift toward inclusion

- ■ Zoom out, consider the system of relationships that led to a solution. Ask how previous designs might be important to future designs.

- ■ Identify a personal connection to an aspect of inclusion that is meaningful to you and your community.

- ■ Study the history of how a solution came to be. Why is it shaped a particular way? Who influenced those decisions, and what was their motivation?