Lisbon

Lisbon's Nightlife

Fado

Mosteiro dos Jerónimos

Azulejos & The Museu Nacional do Azulejo

Lisbon's Trams

Sights

Activities

Tours

Shopping

Eating

Drinking & Nightlife

Entertainment

Lisbon

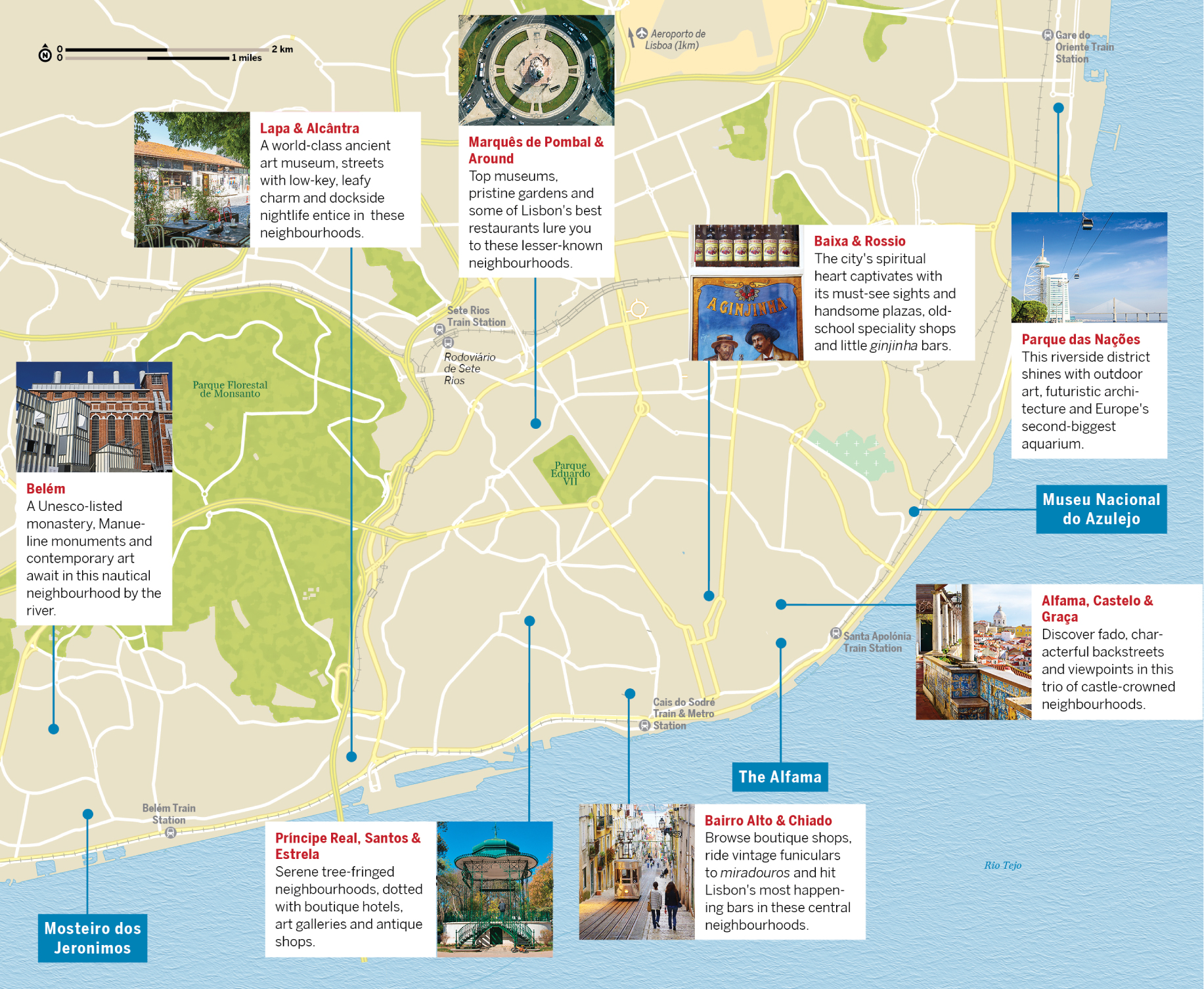

Spread across steep hillsides that overlook the Rio Tejo, Lisbon has captivated visitors for centuries. Windswept vistas reveal the city in all its beauty: Roman and Moorish ruins, white-domed cathedrals, grand plazas. However the real delight of discovery is delving into the narrow cobblestone lanes.

As yellow trams clatter through tree-lined streets, lisboêtas stroll through lamp-lit old quarters. Gossip is exchanged over wine at tiny restaurants as fado singers perform in the background. In other neighbourhoods, Lisbon reveals her youthful alter ego at bohemian bars and late-night street parties. Just outside Lisbon there are enchanting woodlands, gorgeous beaches and seaside villages to discover.

Lisbon in Two Days

Explore Lisbon's old town – the Alfama – on day one, perhaps taking a ride on old tram 28 part of the way. Round off with a fado performance in the evening. On day two explore Belém and the Mosteiro dos Jerónimos. In the evening sample some of Lisbon's famous nightlife.

Lisbon in Four Days

On day three hit the museums – Lisbon has plenty dedicated to a range of subjects, but one highlight is the Museu Nacional do Azulejo packed with traditional tiles. On day four catch the train to Sintra to spend the whole day walking through the boulder-speckled woodlands to fairy-tale palaces.

Arriving in Lisbon

Aeroporto de Lisboa Direct flights to major international hubs including London, New York, Paris and Frankfurt.

Sete Rios bus station The main long-distance bus terminal.

Gare do Oriente bus station Bus services to the north and Spain.

Gare do Oriente train station Lisbon's largest train station.

Sleeping

Lisbon has an array of boutique hotels, upmarket hostels and both modern and old-fashioned guest houses. Be sure to book ahead for high season (July to September). A word to those with weak knees and/or heavy bags: many guest houses lack lifts, meaning you’ll have to haul your luggage up three flights or more. If this disconcerts, be sure to book a place with a lift.

TOP EXPERIENCE

Lisbon's Nightlife

Late-night street parties in Cais do Sodré and Bairro Alto, sunset ginjinhas on Rossio’s sticky cobbles, drinks with indie kids in Santa Catarina – Lisbon has one of Europe’s most eclectic nightlife scenes.

Great For…

yDon't Miss

yDon't Miss

Savour a craft cocktail at Cinco Lounge courtesy of an award-winning, London-born mixologist.

8Need to Know

8Need to Know

Top nightlife neighbourhoods are Cais do Sodré, Bairro Alto, Alfama and the harbour area.

5Take a Break

5Take a Break

There are countless places to eat amid the revelry. Cafe Tati (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %213 461 279; www.cafetati.blogspot.com; Rua da Ribeira Nova 36; mains €7-8;

%213 461 279; www.cafetati.blogspot.com; Rua da Ribeira Nova 36; mains €7-8; ![]() h11am-1am Tue-Sun;

h11am-1am Tue-Sun; ![]() W) has a hip retro feel and is a great place to grab a coffee.

W) has a hip retro feel and is a great place to grab a coffee.

oTop Tip

oTop Tip

Locals don’t even think about showing up at a club before 2am.

Cais do Sodré

For years Cais do Sodré was the haunt of whisky-slugging sailors craving after-dark sleaze. Then in late 2011, the district went from seedy to stylish. Rua Nova do Carvalho was painted pink and the call girls were sent packing, but the edginess and decadence on which Lisbon thrives remains. Now party central, its boho bars, live-music venues and burlesque clubs are perfect for a late-night bar crawl. When someone refers to Pink Street, they mean here.

Bairro Alto & Harbour Area

Bairro Alto is like a student at a house party: wasted on cheap booze, flirty and everybody’s friend. At dusk, the nocturnal hedonist rears its head with bars trying to out-decibel each other, hash-peddlers lurking in the shadows and kamikaze taxi drivers forcing kerbside sippers to leap aside. For a more sophisticated and more artistically minded crowd, head a few blocks south to Bica.

The dockside duo of Doca de Alcântara and Doca de Santo Amaro harbour wall-to-wall bars with a preclubbing vibe. Many occupy revamped warehouses, with terraces facing the river and the lit-up Ponte 25 de Abril. Most people taxi here, but you can take the train from Cais do Sodré to Alcântara Mar or catch tram 15 from Praça da Figueira.

Clubbing Tips

Though getting in is not as much of a beauty contest as in other capitals, you’ll stand a better chance of slipping past the fashion police if you dress smartish and don’t rock up on your lonesome. Most clubs charge entry (around €5 to €20, which usually includes a drink or two), and some operate a card-stamping system to ensure you spend a minimum amount. Many close Sunday and Monday.

Keep in mind club security has the right to dramatically inflate cover charges (€250 in some cases!) in order to discourage entry for those they deem to be potential trouble, whether due to level of intoxication or any other reason. Yes, it's discriminatory. But unfortunately, it's perfectly legal.

Something different

Nightlife in Alfama revolves mostly around fado – the neighbourhood packs in a wide variety of atmospheric live-music venues. Just north of Bairro Alto, Príncipe Real is the epicentre of Lisbon’s gay scene and home to some quirky drinking dens.

Ginjinha

Ginjinha is a sweet cherry liqueur served in tiny bars around the Largo de São Domingos and the adjacent Rua das Portas de Santo Antão.

TOP EXPERIENCE

Fado

Portugal’s most famous style of music is fado (Portuguese for ‘fate’), a simple, wistful genre that emerged in the 19th century working-class neighbourhoods of Lisbon.

Great For…

yDon't Miss

yDon't Miss

The greatest fadista, Amália Rodrigues, was given a place in the Panteão Nacional.

8Need to Know

8Need to Know

The Alfama is the place to head for evenings of fado.

5Take a Break

5Take a Break

Fado performances are almost always accompanied with traditional Portuguese food.

oTop Tip

oTop Tip

Fado evenings usually start around 8pm, finishing around 1am or 2am.

No visit to the Portuguese world is complete without an evening of fado music, the traditional music of Lisbon. A performance in a typical fado house provides an insight into the Portuguese soul, the lilting guitar and vocals evoking a melancholic yearning for the past.

What is Fado?

Although fado is something of a national treasure – in 2011 it was added to Unesco’s list of the World’s Intangible Cultural Heritage – it’s really the music of Lisbon (Coimbra has its own, slightly different version). Fados are traditionally sung by one performer accompanied by a 12-string Portuguese guitarra (pear-shaped guitar). When two fadistas (singers of traditional Portuguese song) perform, they sometimes engage in desgarrada, a bit of improvisational one-upmanship where the singers challenge and play off one another. At fado houses there are usually a number of singers, each one traditionally singing three songs.

History of Fado

No one quite knows fado's origins, though African and Brazilian rhythms, Moorish chants and the songs of Provençal troubadours may have influenced the sound. What is clear is that by the 19th century fado could be heard all over the working-class neighbourhoods of Mouraria and Alfama. It was the anthem of the poor, and it maintained an unsavoury reputation until the late 19th century, when the upper classes took an interest and brought it into the mainstream. Fado’s popularity slipped in the post-revolution days, when the Portuguese were eager to make a clean break with the past. (Salazar spoke of throwing the masses the three F’s – fado, football and Fátima – to keep them happily occupied.) The 1990s, however, saw a resurgence of fado’s popularity, with the opening of new fado houses and the emergence of new performers.

Amália Rodrigues

One singer who played a major role in its popularisation was Amália Rodrigues, the ‘queen of fado’, who became a household name in the 1940s. Born to a poor family in 1920, Amália took the music from the tavern to the concert hall, and then into households via radio and onto film screens, starring in the 1947 film Capas Negras (Black Capes).

Cover Charges and Menus

Most fado places have a minimum cover charge of €15 to €25, though a fixed menu can cost anything up to €50. The quality of food can be hit and miss; if in doubt, it might be worth asking if you can just order a bottle of wine.

TOP EXPERIENCE

Mosteiro dos Jerónimos

One of Lisbon's top attractions is this Unesco-listed monastery, one of the finest examples of the elaborate Manueline style.

Great For…

yDon't Miss

yDon't Miss

The monastery is one of the finest examples of the short Manueline period in Portuguese architecture.

8Need to Know

8Need to Know

Mosteiro dos Jerónimos (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; www.mosteirojeronimos.pt; Praça do Império; adult/child €10/5, 1st Sun of month free; ![]() h10am-6.30pm Tue-Sun, to 5.30pm Oct-May)

h10am-6.30pm Tue-Sun, to 5.30pm Oct-May)

5Take a Break

5Take a Break

Pão Pão Queijo Queijo (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %213 626 369; Rua de Belém 124; mains €4-8;

%213 626 369; Rua de Belém 124; mains €4-8; ![]() h10am-midnight Mon-Sat, to 8pm Sun;

h10am-midnight Mon-Sat, to 8pm Sun; ![]() W

W![]() v) is a popular fastfood stop selling traditional sandwiches and other snacks.

v) is a popular fastfood stop selling traditional sandwiches and other snacks.

oTop Tip

oTop Tip

A €12 admission pass is valid for both the monastery and the nearby Torre de Belém.

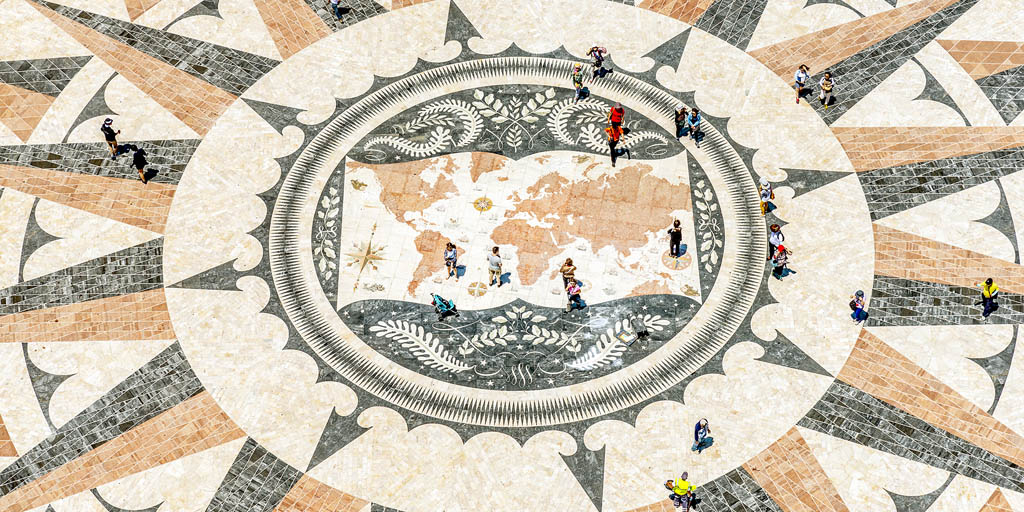

The Monastery's Story

Belém’s undisputed heart-stealer is the stuff of pure fantasy; a fusion of Diogo de Boitaca’s creative vision and the spice and pepper dosh of Manuel I, who commissioned it to trumpet Vasco da Gama’s discovery of a sea route to India in 1498. The building embodies the golden age of Portuguese discoveries and was funded using the profits from the spices Vasco da Gama brought back from the subcontinent. It was begun in 1502 but not completed for almost a century. Wrought for the glory of God, Jerónimos was once populated by monks of the Order of St Jerome, whose spiritual job for four centuries was to comfort sailors and pray for the king’s soul. The monastery withstood the 1755 earthquake but fell into disrepair when the order was dissolved in 1833. It was later used as a school and orphanage until about 1940. In 2007 the now much-discussed Treaty of Lisbon was signed here.

The Church

Entering the church through the western portal, you’ll notice tree-trunk-like columns that seem to grow into the ceiling, which is itself a spiderweb of stone. Windows cast a soft golden light over the church. Superstar Vasco da Gama is interred in the lower chancel, just left of the entrance, opposite venerated 16th-century poet Luís Vaz de Camões. From the upper choir, there’s a superb view of the church; the rows of seats are Portugal’s first Renaissance woodcarvings.

Vasco Da Gama

Born in Alentejo in the 1460s, Vasco da Gama was the first European explorer to reach India by ship. This was a key moment in Portuguese history as it opened up trading links to Asia and established Portugal's maritime empire, the wealth from which made the country into a world superpower. Da Gama died from malaria on his third voyage to India in 1524.

The Cloisters

There’s nothing like the moment you walk into the honey-stone Manueline cloisters, dripping with organic detail in their delicately scalloped arches, twisting auger-shell turrets and columns intertwined with leaves, vines and knots. It will simply wow. Keep an eye out for symbols of the age such as the armillary sphere and the cross of the Military Order, plus gargoyles and fantastical beasties on the upper balustrade.

TOP EXPERIENCE

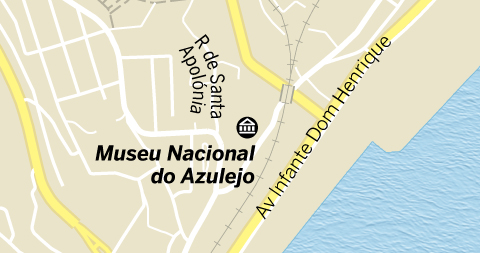

Azulejos & The Museu Nacional do Azulejo

Few visitors fail to be impressed by the exquisite tiles the Portuguese have traditionally used for centuries to decorate their buildings. There's even a museum that tells the story of these azulejos.

Great For

yDon't Miss

yDon't Miss

The museum shop has a superb range of ceramic souvenirs and beautiful coffee-table books.

8Need to Know

8Need to Know

Museu Nacional do Azulejo (

GOOGLE MAP

; www.museudoazulejo.pt; Rua Madre de Deus 4; adult/child €5/2.50, free 1st Sun of the month; ![]() h10am-6pm Tue-Sun)

h10am-6pm Tue-Sun)

5Take a Break

5Take a Break

The museum has its own restaurant.

oTop Tip

oTop Tip

Admission to the museum is free on the first Sunday of the month.

Azulejos

Portugal’s favourite decorative art is easy to spot. Polished painted tiles called azulejos (after the Arabic al zulaycha, meaning polished stone) cover everything from churches to train stations. The Moors introduced the art, having picked it up from the Persians, but the Portuguese wholeheartedly adopted it.

Portugal’s earliest tiles are Moorish, from Seville. These were decorated with interlocking geometric or floral patterns. After the Portuguese captured Ceuta in Morocco in 1415, they began exploring the art themselves. The 16th-century Italian invention of maiolica, in which colours are painted directly onto wet clay over a layer of white enamel, gave works a fresco-like brightness.

The earliest home-grown examples date from the 1580s, and may be seen in churches such as Lisbon’s Igreja de São Roque, providing an ideal counterbalance to fussy baroque.

The late 17th century saw a fashion for huge panels depicting everything from saints to seascapes. As demand grew, mass production became necessary and the Netherlands’ blue-and-white Delft tiles started appearing.

Portuguese tile-makers rose to the challenge of this influx, and the splendid work of virtuosos António de Oliveira Bernardes and his son Policarpo in the 18th century springs from this competitive creativity. You can see their work in Évora, in the Igreja de São João.

By the end of the 18th century, industrial-scale manufacture began to affect quality. There was also massive demand for tiles after the 1755 Lisbon earthquake.

From the late 19th century, the art-nouveau and art-deco movements took azulejos by storm, providing fantastic facades and interiors for shops, restaurants and residential buildings. Today, azulejos still coat contemporary life.

Tile Spotting in the Metro

Maria Keil (1914–2012) designed 19 of Lisbon's stations, from the 1950s onwards – look out for her wild modernist designs at the stations of Rossio, Restauradores, Intendente, Marquês de Pombal, Anjos and Martim Moniz. Oriente also showcases extraordinary contemporary work by artists from five continents.

The Museum

Housed in a sublime 16th-century convent, Lisbon's Museu Nacional do Azulejo covers the entire azulejo spectrum. Star exhibits feature a 36m-long panel depicting pre-earthquake Lisbon, a Manueline cloister with web-like vaulting and exquisite blue-and-white azulejos, and a gold-smothered baroque chapel.

Here you'll find every kind of azulejo imaginable, from early Ottoman geometry to zinging altars, scenes of lords a-hunting to Goan intricacies. Bedecked with food-inspired azulejos – ducks, pigs and the like – the restaurant opens onto a vine-clad courtyard.