THE horned dinosaurs, Ceratopsia, are among the most familiar dinosaurs to us. Triceratops, usually in combat with a Tyrannosaurus rex, has been a staple of dinosaur movies for decades. Less familiar are the dome-headed dinosaurs, Pachycephalosauria, close relatives of the ceratopsians. Here, I examine the anatomy, classification, evolution, and probable habits of these two groups of dinosaurs.

Most paleontologists have concluded that the ceratopsians and pachycephalosaurs share an evolutionary ancestry that justifies linking them into a single group called

Marginocephalia (

figure 9.1). This is despite the fact that, on first appearance, horned and dome-headed dinosaurs appear to be strikingly different. But, a few key evolutionary novelties—especially the development of at least a small

frill (a shelf of bone projecting from the back of the skull)—suggest a close relationship between the two groups. Marginocephalian dinosaurs were primarily of Late Cretaceous age. They were plant-eating ornithischians closely related to ornithopods.

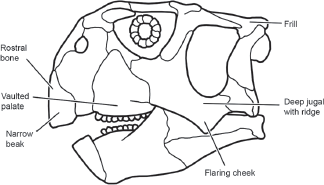

Ceratopsian dinosaurs were one of the most diverse groups of plant-eating dinosaurs of the Late Cretaceous. They comprise at least two groups: the primitive ceratopsians, well represented by the genus

Psittacosaurus, from the Early Cretaceous of Asia, and Neoceratopsia, from the Jurassic–Cretaceous of Asia and Cretaceous of North America. Evolutionary novelties that unite ceratopsians are the presence of a rostral (in the snout) bone in the skull, a skull with a narrow beak and flaring jugals (cheeks), a deep jugal with a distinct ridge, a frill, and a highly vaulted palate in the front of the mouth (

figure 9.2). The morphology and distribution of ceratopsian fossils suggest the ceratopsians originated in Asia and spread to North America, where they were highly successful until their extinction at the end of the Cretaceous. They were among the last dinosaurs.

FIGURE 9.1

Ceratopsians and pachycephalosaurs share an ancestry and thus represent one group of dinosaurs, the Marginocephalia. (Drawing by Network Graphics)

FIGURE 9.2

This skull of Psittacosaurus shows the key evolutionary novelties of the ceratopsians. (© Scott Hartman)

The “parrot dinosaur,”

Psittacosaurus, well represents a primitive ceratopsian (

figure 9.3). As many as seven species of

Psittacosaurus are known from the Lower Cretaceous of eastern Asia, and their remains include many complete skulls and skeletons and even skin impressions (see

box 13.1). Recently discovered early and primitive ceratopsians include the Late Jurassic

Yinlong and

Chaoyangsaurus from China. For many years, psittacosaurs had been allied with the ornithopods, but analysis of their excellent fossil record supports the identification of

Psittacosaurus as an early ceratopsian.

Psittacosaurus possessed all the key evolutionary novelties of the Ceratopsia, even though it had only the most rudimentary of frills. Indeed, the posterior end of the skull roof just barely overhung the back end of the skull. The short snout, the high position of the nostrils, the tall rostrum (“snout”) that superficially resembled a parrot’s beak, and the reduction of the functional toes of the hand to three are diagnostic features of

Psittacosaurus among ceratopsians.

FIGURE 9.3

Early Cretaceous Psittacosaurus was a characteristic primitive ceratopsian. (© Scott Hartman)

The cheek teeth of Psittacosaurus had broad, flat wear surfaces with self-sharpening edges but did not occlude precisely. Their placement in the jaws was inset from the sides of the skull, suggesting the presence of cheek pouches. Psittacosaurus did not exceed 2 meters in length, and its skeletal structure was much more like that of a primitive ornithischian than other ceratopsians. In particular, the hind limb was longer than the forelimb, and the forefoot had only three functional toes, whereas the hind foot had four slender toes. The neck was short, and the tail was moderately long. Ossified tendons were present in some species of Psittacosaurus along the spine in the back and hip region.

The teeth of psittacosaurs were characteristic of plant eaters. They were usually well worn, and polished stones (gastroliths) associated with some psittacosaur skeletons suggest that significant amounts of vegetation were milled in the stomach. The forelimbs of

Psittacosaurus were about 58 percent of the hind limb length, indicating this dinosaur was a facultative biped. Psittacosaurs were probably able to grasp with their hands; their first finger diverged from the other two (see

figure 9.3). If this was the case, psittacosaurs were primarily bipeds, using the hands to grasp vegetation while eating.

The psittacosaurs were widespread and reasonably common dinosaurs in Asia during the Early Cretaceous. They represent well an early stage in ceratopsian evolution that preceded a much more diverse and impressive group of dinosaurs, the Neoceratopsia.

If you had visited a Late Cretaceous landscape in western North America, you would surely have seen a neoceratopsian. These dinosaurs were among the most diverse and abundant dinosaurs at that time and place. Neoceratopsians include an array of primitive genera, mostly Asian, as well as the Asian and western North American ceratopsids. Evolutionary novelties that distinguish the neoceratopsians from the psittacosaurs include an extremely large head, a broad and prominent frill, a pointed and sharply keeled rostrum, and limb structures associated with obligate quadrupedalism (

figure 9.4).

FIGURE 9.4

Late Cretaceous Protoceratops was a characteristic primitive neoceratopsian. (© Scott Hartman)

The fossil record of neoceratopsians is one of the best of any group of dinosaurs. Many complete skeletons have been discovered, and well-preserved skulls are common.

Most primitive neoceratopsians were of Late Cretaceous age, but they truly represent a stage of ceratopsian evolution intermediate between the psittacosaurs and the ceratopsids. These small (1 to 2.5 meters long), primitive Late Cretaceous neoceratopsians include the well-known genera

Protoceratops (see

figure 9.4) and

Bagaceratops from Mongolia and

Montanoceratops and

Leptoceratops from North America. Early Cretaceous neoceratopsians include

Liaoceratops from China and

Aquilops from North America.

Protoceratops, here considered a typical primitive neoceratopsian, had a relatively larger skull and a much longer frill than Psittacosaurus. The fore- and hind limbs of Protoceratops were of more nearly equal lengths than those of Psittacosaurus, and the limbs were more massive with broader feet. In these features, Protoceratops was much more like a ceratopsid than was Psittacosaurus.

Yet, unlike ceratopsids, the frill of Protoceratops was still rather short, Protoceratops had no horns, and its nostrils were small. These features identify Protoceratops as a neoceratopsian more primitive than the ceratopsids. Indeed, the ancestors of the ceratopsids must have looked similar to Protoceratops.

FIGURE 9.5

Differences in skull size and shape distinguished male and female Protoceratops. (© Scott Hartman)

Fossils of Protoceratops come from areas that were deserts during the Late Cretaceous. In those deserts, extensive dune fields were dotted by intermittent lakes and streams. The dozens of skeletons and skulls of Protoceratops found suggest that these dinosaurs nested communally and were gregarious.

Measurements of

Protoceratops indicate that as adults, these dinosaurs had skulls of two different shapes (

figure 9.5). One type of skull had a larger and more erect frill than the other, as well as a prominent bump on the snout. It seems likely, by analogy with living animals, that these two skull types represent males and females of a single species of

Protoceratops.

We can thus envision groups of Protoceratops living in the deserts of Central Asia during the Late Cretaceous and foraging for the vegetation that grew in wetter places in the desert.

The

Ceratopsidae were large (4 to 8 meters long) habitual quadrupeds. Their distinctive evolutionary novelties include very large skulls (1 to 2.8 meters long), large nostrils, prominent frills, and a variety of horns (

figure 9.6). Ceratopsids are known primarily from the Late Cretaceous of North America. One ceratopsid,

Turanoceratops, is known from the Late Cretaceous of Asia.

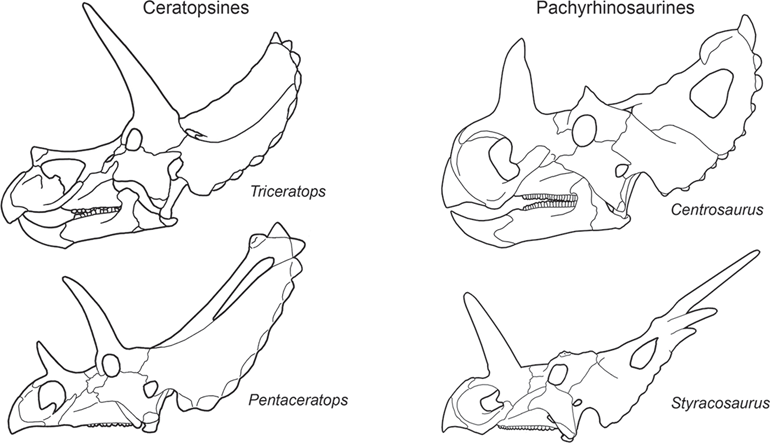

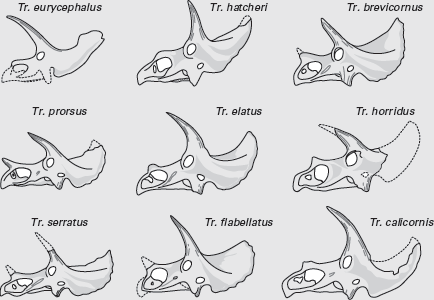

Paleontologists recognize two different types of ceratopsids:

Pachyrhinosaurinae and

Ceratopsinae (

figure 9.7). The pachyrhinosaurines are considered the more primitive of the two because they had a relatively short, high face and a short frill. They also had horns near the nostrils (nasal horns) that were much larger than the paired horns behind the eyes (postorbital horns). In contrast, the more advanced ceratopsines had long, low faces, long frills, and postorbital horns that were usually larger than the nasal horns. Ceratopsines include the largest of all ceratopsids,

Torosaurus,

Triceratops, and

Pentaceratops, which had skulls as much as 2.8 meters long and bodies up to 8 meters long.

FIGURE 9.6

The skulls of ceratopsids encompassed a variety of horn types and frill shapes. (© Scott Hartman)

FIGURE 9.7

Paleontologists distinguish two types of ceratopsids, pachyrhinosaurines and ceratopsines, based on skull features. Pachyrhinosaurines had relatively short, high faces, short frills, and nasal horns larger than the postorbital horns. Ceratopsines had long, low faces, long frills, and postorbital horns larger than the nasal horns. (© Scott Hartman)

Pachyrhinosaurine fossils are known primarily from Montana, Alberta, and Alaska. Ceratopsines, however, were more widespread. Their fossils extend from Alberta to Texas, and fragmentary ceratopsid fossils from Alaska and Mexico may also be of ceratopsines. Triceratops is the most famous ceratopsine, and I examine it here as a typical ceratopsid.

In many ways,

Triceratops is a typical ceratopsine (

figure 9.8). It had a long, low snout and large postorbital horns. But, unlike other ceratopsines (see

figure 9.7),

Triceratops had a short frill that lacked openings (fenestrae). The edge of the frill of

Triceratops was lined with small, conical bones called epoccipitals, a feature seen in some other ceratopsids, including

Centrosaurus and

Pentaceratops.

As in all ceratopsids, the teeth of

Triceratops formed a complex dental battery, in which adjacent teeth were locked together in longitudinal rows and vertical columns (

figure 9.9). As the teeth along the cutting edge wore out, they were lost and replaced from below by new teeth. Ceratopsid teeth and dental batteries were thus very similar (convergent) to those of some hadrosaurids (see

chapter 7).

FIGURE 9.8

Late Cretaceous Triceratops was a characteristic ceratopsid. (© Scott Hartman)

FIGURE 9.9

Ceratopsid teeth formed a complex dental battery. (Drawing by Network Graphics)

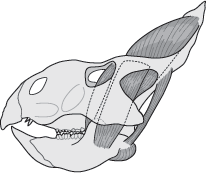

To move the jaws and operate its dental battery,

Triceratops had large jaw-moving muscles anchored in the frill. Three forward-pointing horns projected from the skull: two large ones above each orbit and a much smaller one above the nostril. The bone of these horns, the frill, and much of the skull bore numerous grooves and channels for blood vessels. It seems likely that the horns of

Triceratops had keratinous sheaths, as do the horns of living cows.

As in other ceratopsids, the forelimbs and hind limbs of Triceratops were of nearly equal length, thus identifying these dinosaurs as obligate quadrupeds. This interpretation is supported by the short, slender tail of Triceratops, which clearly was not used as a counterbalance for walking. Ossified tendons were present only in the hip region of Triceratops, and the pelvis was fused to the backbone along 10 sacral vertebrae, four or five more than was usual among dinosaurs.

The solid fusion of the backbone and hip of

Triceratops suggests great stability and power when walking. The massive hind limbs with four broad, hooved toes are consistent with this idea. The deep rib cage of

Triceratops supported a massive shoulder girdle and forelimbs. The forelimbs were held in a sprawling posture, whereas the hind limbs were upright, though this has been debated (

box 9.1). The first four vertebrae of the neck were fused together (co-ossified) to provide extra support for the extremely heavy head.

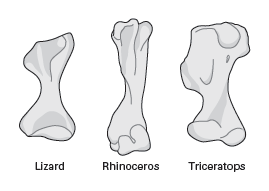

All paleontologists agree that the hind limbs of ceratopsians were held in an upright stance with the limbs essentially vertical and almost directly under the pelvis. But, sharp differences of opinion exist as to how the forelimbs were held by ceratopsians. Some paleontologists favor a semi-sprawling or sprawling forelimb in which the ceratopsian humerus was held obliquely or even parallel to the ground. Others favor a fully upright forelimb posture in which the humerus was held vertical to the ground (

box figure 9.1A). Indeed, a ceratopsian trackway from Colorado indicates the dinosaur walked with nearly upright (semi-sprawling) forelimbs (see

figure 12.6).

The most rigorous analyses of ceratopsian forelimb posture based on bones favor the sprawling or semi-sprawling stance. These studies argue that the shape of the ceratopsian humerus, the size and shape of the shoulder and elbow joints, and the inferred alignment of forelimb muscles based on these shapes, make a habitually upright forelimb in ceratopsians impossible.

We can easily gain some insight into these analyses by comparing the humerus of a living lizard (a sprawler), a living rhinoceros (an upright walker) and a

Triceratops (

box figure 9.1B). The

Triceratops humerus most closely resembles that of the lizard in having broad flanges of bone designed for the attachment of large shoulder (deltoid) and chest (pectoral) muscles. In the lizard, these relatively large muscles are needed to hold and move the humerus horizontally while walking. In contrast, the rhinoceros does not have such relatively large shoulder and chest muscles (or bony attachments for them on its humerus), because it walks with its legs vertical. Given the shape of the humerus of

Triceratops and other ceratopsians, it is most reasonable to conclude that these dinosaurs walked with the humerus in a semi-sprawling or sprawling posture.

BOX FIGURE 9.1A

Some paleontologists have argued that ceratopsians held the forelimb vertically. (© Scott Hartman)

BOX FIGURE 9.1B

When the humeri of a living Komodo dragon, a living rhinoceros, and a Triceratops are compared, it is easy to see that the ceratopsian most resembles the lizard. (Drawing by Network Graphics)

Nevertheless, the only known ceratopsian footprints seem to indicate an upright forelimb posture. The bone and footprint evidence thus present a contradiction not easy to resolve. Perhaps the answer lies in suggesting that Triceratops held the forelimb with at least a bit of a sprawl and twisted the backbone and front part of the body, so that the forefeet were planted much closer together when walking than normally occurs when walking on a sprawling limb.

FIGURE 9.10

The frills of ceratopsians provided sites for the attachment of jaw muscles. (Drawing by Network Graphics)

We usually see artistic depictions of Triceratops in a defensive posture, fending off the attack of a large meat-eating dinosaur with its horns and frill. But, a careful examination of ceratopsian horns and frills suggests that these were not primarily defensive structures. Indeed, the horns and frills probably performed several functions.

The large muscles that opened and closed the jaws of ceratopsians were attached mainly to the frill (

figure 9.10). Different sizes and shapes of frills and their fenestrae probably reflected differences in the jaw muscles of various ceratopsians. The extremely large frills of neoceratopsians provided attachment sites for enormous jaw muscles that exerted great chewing force.

Beyond its relationship to chewing, the ceratopsian frill (and horns) must have functioned in display. Different frill sizes and shapes were probably species-specific identifiers and, within some species, may also have expressed sexual dimorphism. Analyses of variation in frill size and shape in

Protoceratops and

Chasmosaurus suggest that males and females of the same species differed in features of the frill, horns, and other parts of the skull (see

figure 9.5). Similar kinds of differences between males and females of the same species are seen among some living mammals. Deer, in which male and female horns (antlers) differ, are a good example.

Another possible function of the ceratopsian frill was thermoregulation. Ceratopsian frills were highly vascularized; the bone contained numerous canals and grooves for blood vessels (

figure 9.11). Like the plates of

Stegosaurus (see

chapter 8), the ceratopsian frill could have been used to spread the dinosaur’s blood over a wide surface area, thus allowing for rapid heating and cooling. The frill of ceratopsians consisted of highly vascularized bone that in life was covered with huge, jaw-closing muscles. It is difficult to envision the frill as a helmet or shield used in combat. The horns might have had some defensive function, but a primary use in display seems more likely.

FIGURE 9.11

The frill of Triceratops was highly vascularized: it was covered with channels and grooves for blood vessels. (© Scott Hartman)

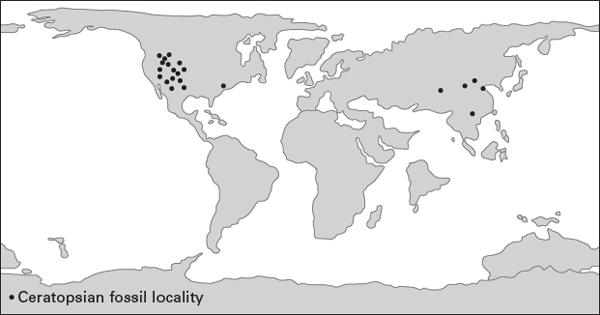

Ceratopsians first appeared in Asia during the Late Jurassic, about 160 million years ago. Although the horned dinosaurs shared an ancestry with the ornithopods, that common ancestor has not yet been discovered.

Isolated bones and teeth of ceratopsians in Lower Cretaceous strata of North America are not as old as the earliest Asian ceratopsians. Indeed, Yinlong and Chaoyangsaurus, from the Upper Jurassic of northeastern China, are the oldest ceratopsians. Liaoceratops, from the Lower Cretaceous of northeastern China, is the earliest neoceratopsian and the same age as the psittacosaurs. Aquilops, from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana, and Zuniceratops, from the Upper Cretaceous of New Mexico, are the oldest well-known North American neoceratopsians. This suggests not only that ceratopsians originated in Asia, but that the origin of neoceratopsians must have taken place in Asia early in ceratopsian evolution.

The modest diversification of Asian ceratopsians culminated in

Protoceratops. By 100 million years ago, ceratopsians had emigrated from Asia to western North America, where they became remarkably successful (

figure 9.12). They were among the most common and most diverse of the Late Cretaceous plant-eating dinosaurs. Indeed,

Triceratops was one of the last known dinosaurs (

box 9.2).

FIGURE 9.12

Ceratopsian fossils are known from only Asia and North America (continent position is for the Late Cretaceous). (Drawing by Network Graphics)

No one else has collected ceratopsians like John Bell Hatcher. From 1889 to 1892, Hatcher collected 32 ceratopsian skulls in eastern Wyoming and shipped them to Yale University. Most of those skulls belong to Triceratops, and they formed much of the basis for some of the 16 species of Triceratops named during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This great diversity of Triceratops species has long played a major role in the ideas about dinosaur extinction. This is because these ceratopsians were among the last dinosaurs, and their great diversity supports the notion of dinosaur prosperity just prior to their extinction.

However, paleontologists John Ostrom of Yale University and Peter Wellnhofer of the Bavarian State Museum in Munich, Germany, challenged the idea of many species of Triceratops at the end of the Cretaceous. These paleontologists were motivated by a desire to answer a nagging question: Did so many different species of Triceratops inhabit the area from Colorado to Wyoming to Montana during a mere 2 million years? Indeed, today, and at many times during the past, large terrestrial vertebrates (such as elephants) are not very speciose—one species generally covers a very wide geographic range. A good example is provided by North American bison during and since the last “Ice Age,” when no more than three species were indigenous to North America.

So, how many species of

Triceratops were there? According to Ostrom and Wellnhofer, only one! They concluded so because the variation in horn and skull shape among

Triceratops is comparable to the variation in horn and skull shape we see today in a single species of bovid (

box figure 9.2). Ostrom and Wellnhofer pointed out that, formerly, paleontologists believed every

Triceratops skull of a different shape represented a different species. Instead it is likely that a single “herd” of

Triceratops from Late Cretaceous Wyoming would have encompassed all the variety in skull and horn structure seen in the 16 previously named species of

Triceratops.

BOX FIGURE 9.2

Skulls of Triceratops from the Late Cretaceous of Wyoming show variation that led paleontologists to name many different species. (Drawing by Network Graphics)

Ostrom and Wellnhofer’s reduction of the species of

Triceratops from 16 to one is not above criticism. It would certainly be best to have a sample of

Triceratops skulls from a single location. Such a sample would closely approximate an extinct population of these dinosaurs and thus allow an accurate assessment of skull and horn variation in a single

Triceratops species. But, even if Ostrom and Wellnhofer are wrong, and there were as many as five different species of

Triceratops, it is still far fewer than the 16 named by earlier paleontologists. So, our view of the prosperity of these ceratopsians just prior to dinosaur extinction needs to be revised.

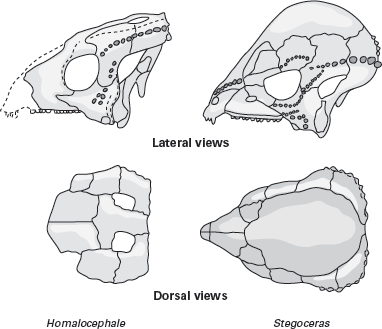

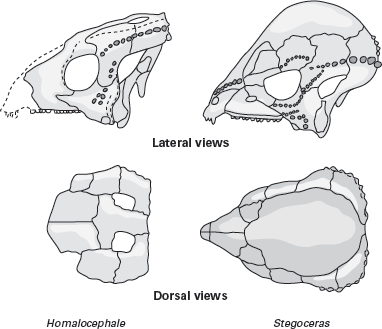

The thick-headed dinosaurs, pachycephalosaurs, were bipedal ornithischians with greatly thickened bones of the skull roof. Primitive pachycephalosaurs and the dome-headed Pachycephalosauridae encompass 15 known genera from the Cretaceous of North America and Asia.

Pachycephalosaurs were long divided into two groups: the primitive, flat-headed taxa (formerly a family, Homalocephalidae) and the derived, dome-headed taxa (

Pachycephalosauridae). Now, the primitive pachycephalosaurs are seen as an array of taxa, not a monophyletic family. However, some paleontologists argue that most or all of the flat-headed pachycephalosaurs are actually juveniles (representing early growth stages) or females of the dome-headed pachycephalosaurids (

box 9.3).

The primitive pachycephalosaurs were characterized by a flat, table-like skull roof, which was of even thickness from side to side and pitted dorsally (

figure 9.13). In addition, the skulls of primitive pachycephalosaurs had open supratemporal fenestrae, and short canine-like teeth were present in both the upper and lower jaws. The remaining teeth, however, were small and had sharp, serrated edges for slicing vegetation.

Well known and characteristic of the primitive pachycephalosaurs is

Dracorex, from the Upper Cretaceous of the United States (see

box 9.3). The postcranial skeletons of primitive pachycephalosaurs are little known.

Pachycephalosaurids were advanced pachycephalosaurs characterized by a prominent, dome-like thickening of the skull roof and no supratemporal openings (see

box 9.3). The dome was produced by the fusion and thickening of the frontal and parietal bones. It is important to stress that it was these bones that were thickened; the volume of the brain of pachycephalosaurids did not increase (

figure 9.14). Unlike the flat skull roofs of primitive pachycephalosaurs, the domed skull roofs of pachycephalosaurids were smooth, not pitted.

For decades, paleontologists viewed the flat-headed pachycephalosaurs as a distinct family, Homalocephalidae, more primitive than the dome-headed pachycephalosaurs, the Pachycephalosauridae. However, in 2009, paleontologists John Horner and Mark Goodwin made a startling suggestion. They argued that at least some (if not all) of the flat-headed skulls were those of juveniles of the dome-headed pachycephalosaurs. In other words, during growth the skull of a pachycephalosaur changed dramatically, from flat-topped with open supratemporal fenestrae and strange nodes and horns to the massively domed skull characteristic of pachycephalosurids. Thus, as the skull became larger, the dome developed from the parietal bones, inflating and burying the fenestra, though the nodes, and horns remained.

This idea posits that the flat-headed pachycephalosur

Dracorex is a younger growth stage of the dome-headed

Pachycephalosaurus (

box figure 9.3). Similar dramatic changes in growth have also been proposed for ceratopsids. One suggestion is that the very large ceratopsid

Torosaurus is an advanced growth stage of

Triceratops.

Some paleontologists have referred to these ideas as the identification of ontogomorphs—the development of very different anatomy (morphology) due to growth (ontogeny). The case for some dinosaur ontogomorphs appears to be strong. However, a criticism of some of the proposed ontogomorphs is that they are not based on actual growth series from a single population sample of the dinosaurs that includes both juveniles and adults. Until such samples are discovered, the cases for some ontogomorphs remain interesting possibilities requiring further documentation.

BOX FIGURE 9.3

Some paleontologists identify Pachycephalosaurus (above) as an ontogomorph of Dracorex (center and below). (Courtesy Robert M. Sullivan)

FIGURE 9.13

The skull of Homalocephale is characteristic of primitive pacycephalosaurs, whereas that of Stegoceras typifies the pachycephalosaurids. (Drawing by Network Graphics)

There are at least 14 species of pachycephalosaurids known from the Cretaceous of North America and Asia. The North American genus

Stegoceras is the best known and is typical of the family (

figure 9.15).

The skull of Stegoceras had the high, smooth dome characteristic of pachycephalosaurids. In addition, a bony shelf was present around the dome. No supratemporal openings remained. The teeth of Stegoceras were similar to those of primitive pachycephalosaurs and indicate plant-eating.

No complete pachycephalosaurid skeleton is known, but the best known skeleton, that of

Stegoceras (see

figure 9.15), indicates that pachycephalosaurids had many of the features we associate with ornithopods. Thus,

Stegoceras had much longer hind limbs than forelimbs and a long tail with vertebrae tightly connected by ossified tendons. It is features such as these that long justified the inclusion of the pachycephalosaurids in the Ornithopoda. Indeed, some paleontologists dismiss the apparent similarities of ceratopsians and pachycephalosaurs and regard the Pachycephalosauria as specialized, Late Cretaceous derivatives of ornithopods.

Unique features of the pachycephalosaurid postcranial skeleton are numerous. They include the long and low ilium bone of the pelvis, which contacted six to eight sacral vertebrae. Also, the joint surfaces between pachycephalosaurid vertebrae were ridged, and thus “locked” together, to stabilize the back. Finally, the head of a pachycephalosaurid was set at an angle to its vertebral column; in a normal posture, the head would have hung down so that the nose pointed at the ground and the “dome” pointed forward.

FIGURE 9.14

Pachycephalosaurids had greatly thickened bones in their skull roof but did not experience an increase in brain volume. (Drawing by Network Graphics)

FIGURE 9.15

This skeletal reconstruction of Stegoceras is the most complete that can be made for any pachycephalosaur. (© Scott Hartman)

The function of the peculiar, thickened skulls of pachycephalosaurids has long fascinated paleontologists. Some paleontologists argue that pachycephalosaurids used their skulls to

head-butt against other dinosaurs, including each other (

figure 9.16), much as do many living bovids. Features of the pachycephalosaurid skull and skeleton designed to resist impacts include the following:

• The greatly thickened dome of the skull, which protected the brain

• The shortened base of the skull

• The inclination of the skull relative to the vertebral column

• The widely expanded back of the skull

• The strengthening of the vertebral column, described earlier

• The reinforced upper lip of the hip socket

All of these features support the idea that pachycephalosaurids either directly butted heads or used their heads to butt the flanks of other pachycephalosaurs (or other dinosaurs). However, some paleontologists argue that head-butting by pachycephalosaurids is unlikely. Head-butting would have required the relatively small domes to impact each other, and the shape of the bones of the pachycephalosaurid skull indicate that impact forces would have been directly transmitted to the brain, which would have produced serious fractures in cervical vertebrae.

FIGURE 9.16

Some paleontologists believe pachycephalosaurs butted heads to defend territory and maintain their social structure. (© Mark Hallett. Reproduced with permission of Mark Hallett Paleoart)

Today, head- and flank-butting occur in mammals such as bighorn sheep. The butting is usually performed in competition among males for territory and/or access to females. If we conclude that pachycephalosaurids butted the heads and flanks of each other and other dinosaurs, then it was likely for the same social reasons as these living mammals.

The evolutionary history of the pachycephalosaurs is similar to the history of the Ceratopsia, though all bona fide pachycephalosaurs are of Late Cretaceous age. Likely originating in Asia, primitive pachycephalosaurs underwent a limited diversification and emigrated to North America, where a few taxa (or ontogomorphs) were present during the Late Cretaceous (see

box 9.3). A more diverse group of advanced pachycephalosaurs (pachycephalosaurids) lived in North America, from Alberta to Texas.

The distribution of pachycephalosaur fossils indicates they preferred inland rather than coastal environments. In rocks deposited on coastal plains, pachycephalosaur fossils consist mostly of isolated and highly durable skullcaps, which may have been transported many kilometers by rivers. The most complete, well-preserved, and numerous of pachycephalosaur fossils are found in rocks deposited on inland floodplains and in deserts.

The structures for possible head-butting in the skulls and skeletons of pachycephalosaurids suggest social behavior like that of some living sheep and goats. It is tempting to speculate that pachycephalosaurids lived in herds and defended territory, maintaining their social structure by butting heads.

In North America, pachycephalosaurs existed through nearly the end of the Cretaceous. They were among the last dinosaurs.

1. Ceratopsians and pachycephalosaurs are closely related and belong to a single group of dinosaurs, the Marginocephalia.

2. Ceratopsians consist of at least two groups, primitive ceratopsians and neoceratopsians, distinguished from other dinosaurs by features of the skull that include the presence of a frill.

3. Psittacosaurus, from the Lower Cretaceous of Asia, well represents a primitive ceratopsian. Neoceratopsians differed from Psittacosaurus in their extremely large heads, prominent frills, and pointed, sharply keeled beaks.

4. Protoceratops was a characteristic primitive neoceratopsian from the Cretaceous of Asia and North America with short frills and no horns.

5. Ceratopsids were advanced neoceratopsians from the Cretaceous of North America with long frills and horns.

6. Pachyrhinosaurines, with relatively short faces and frills, were primitive ceratopsids.

7. Ceratopsines, with relatively long faces and frills, were advanced ceratopsids.

8. The horns and frills of neoceratopsians functioned in display and thermoregulation, and the frills provided attachment sites for the jaw muscles. They were not primarily used in defense.

9. Ceratopsians lived during the Jurassic and Cretaceous in Asia and the Cretaceous in North America. They were most successful during the Late Cretaceous in western North America where ceratopsids were among the last dinosaurs.

10. Pachycephalosaurs were bipedal ornithischians with greatly thickened bones of the skull roof.

11. Primitive pachycephalosaurs had flat skull roofs ornamented with pits.

12. Advanced pachycephalosaurs, the Pachycephalosauridae, had smooth, domed skull roofs.

13. Pachycephalosaurid skulls and skeletons contain a variety of features that suggest these dinosaurs may have head-butted like some modern sheep and goats.

14. Pachycephalosaurs lived during the Late Cretaceous in North America and Asia.

Aquilops

Ceratopsia

Ceratopsidae

Ceratopsinae

Dracorex

frill

head-butt

Marginocephalia

Neoceratopsia

ontogomorph

Pachycephalosauria

Pachycephalosauridae

Pachyrhinosaurinae

Protoceratops

Psittacosaurus

Stegoceras

Triceratops

1. What evolutionary novelties are shared by ceratopsians and pachycephalosaurs to unite them as marginocephalians?

2. What features distinguish Psittacosaurus from neoceratopsians?

3. Describe the lifestyle of Protoceratops.

4. What features of Triceratops identify it as a typical ceratopsine? How is it different from a pachyrhinosaurine?

5. Discuss and evaluate the possible functions of the horns and frills of ceratopsians.

6. How are primitive pachycephalosaurs distinguished from derived pachycephalosaurids?

7. Why do some paleontologists think pachycephalosaurs butted heads? Why might pachycephalosaurs have done this?

8. What are the similarities and differences in the evolution of ceratopsians and pachycephalosaurs?

Farke, A. A., W. D. Maxwell, R. L. Cifelli, and M. J. Wedel. 2014. A ceratopsian dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of western North America, and the biogeography of Neoceratopsia. PLoS ONE 9:e112055. (Describes Aquilops, an Early Cretaceous neoceratopsian from Montana)

Forster, C. A. 1996. Species resolution in Triceratops: Cladistic and morphometric approaches. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16:259–270. (Argues that there are two valid species of Triceratops)

Galton, P. 1970. Pachycephalosaurids—dinosaurian battering rams. Discovery 6:23–32. (Discusses the head-butting habits of pachycephalosaurs)

Horner, J. R., and M. B. Goodwin. 2009. Extreme cranial ontogeny in the Upper Cretaceous dinosaur Pachycephalosaurus. PLoS ONE 4: e7626. (Argues that Pachycephalosaurus is an ontogomorph of some of the flat-headed pachycephalosaurs)

Lehman, T. M. 1989. Chasmosaurus mariscalensis, sp. nov., a new ceratopsian dinosaur from Texas. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 9:137–162. (Technical article describing the variation in a sample of Chasmosaurus from a bonebed in Texas)

Longrich, N. R., J. T. Sankey, and D. Tanke. 2010. Texascephale langstoni, a new pachycephalosaurid (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the upper Campanian Aguja Formation, southern Texas, USA. Cretaceous Research 31:274–284. (Describes a new pachycephalosaurid and reviews pachycephalosaurid phylogeny)

Mackovicky, P. 2012. Marginocephalia, pp. 527–549, in M. K. Brett-Surman, T. R. Holtz, Jr., and J. O. Farlow, eds., The Complete Dinosaur. 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. (Concise review of the marginocephalians)

Ostrom, J. H., and P. Wellnhofer. 1986. The Munich specimen of Triceratops with a revision of the genus. Zitteliana 14:111–158. (Discusses the taxonomy of the species of Triceratops)

Ryan, M. J., B. J. Chinnery-Allgeier, and D. A. Eberth, eds. 2010. New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. (Collection of 36 articles on recent ceratopsian research)

Scannella, J. B., and J. R. Horner. 2010. Torosaurus Marsh, 1891, is Triceratops Marsh, 1889 (Ceratopsidae: Chasmosaurinae): Synonymy through ontogeny. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30:1157–1168. (Argues that Torosaurus is an ontogomorph of Triceratops)

Sullivan, R. M. 2006. A taxonomic review of the Pachycephalosauridae (Dinosauria: Ornithischia).

Bulletin of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science 35:347–365. (Taxonomic review of all pachycephalosurs)

Xu, X., C. A. Forster, J. M. Clark, and J. Mo. 2006. A basal ceratopsian with transitional features from the Late Jurassic of northwestern China. Proceedings of the Royal Society B273:2135–2140. (Description of Yinlong, the oldest ceratopsian)

Horned dinosaurs are a mainstay of all dinosaur museums, and you can find a skull or skeleton (at least a replica) in just about all of the world’s natural history museums. A replica of the skull of Triceratops is on The Mall in front of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History (Washington, D.C.). Go inside the Museum to see more of Triceratops. At the American Museum of Natural History (New York), you can study the growth series (from babies to adults) on display of the small horned dinosaur Protoceratops. These fossils were collected from Cretaceous rocks in Mongolia by the fabled Central Asiatic Expeditions led by Roy Chapman Andrews in the 1920s. In front of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History (New Haven, Connecticut) stands a sculpture of Torosaurus; the real skull, named by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1891, is on display inside. In Boston, the Museum of Science has a huge (7-meter-long) Triceratops skeleton nicknamed “Cliff.” And, there is also “Bob,” a Triceratops on display at the Barnes County Historical Society (Valley City, North Dakota). Triceratops is the official state fossil of South Dakota, and at the Museum of the Black Hills Institute of Geological Research in Hill City, a replica of a fossilized skin impression of Triceratops is on display.