CHAPTER FOUR

Blood Libels and Cultures of Knowledge in Early Modern Europe

REGIONAL DIFFERENCES WERE EVIDENT not only in the iconography and reception of Simon’s cult but also in the content of Christian knowledge about Jews and their ceremonies and, relatedly, the sources of that knowledge. It would be difficult to overestimate the role that early printed works played in shaping these regional epistemological trajectories. Although still steeped in medieval traditions, many early printed chronicles expanded their scope from regional or monastic contexts to tell “a universal history.” Readers of those chronicles encountered Jews there even if they did not seek out works devoted to Jewish topics because inserted into their narration of the world or of European or regional histories were “events” and stories about Jews. With these chronicles Jews entered into the broader Christian memory of the past, but the role these Jewish characters played in that past molded the way readers would view Jews or “the Jews.” Early printing also shaped more explicit Christian literature about Jews. In Italy and in German lands, Christian Hebraism meant that some Christians could read Jewish books. Although this knowledge was marshaled for polemical purposes, often to discredit Judaism and provide Christians with arguments against Jews, it nonetheless, with few exceptions, provided enough knowledge of Jewish customs to counter or at least mitigate accusations against the Jews.

This was not the case in Poland-Lithuania. There, as elsewhere, the earliest books about Jews shaped subsequent literature for centuries to come. But the first books about Jews were published in Poland decades after the beginning of the Reformation, which had spurred among Catholics fears of heresy and non-Catholic sources of knowledge. This made works published by Christian Hebraists, many of whom were Protestants, suspicious; it also limited what literature about Jews became available in Poland. In the end, in Poland there would be no vernacular or even Latin equivalent to books penned by Christian Hebraists in German lands and on the Italian peninsula or to works written by Jewish converts to Christianity in German lands.1 What Christians in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth absorbed about Jews from books became limited to explicitly anti-Jewish vernacular works by writers who had never studied Jewish texts. And although unlettered Christians might have learned about Jewish practices through personal interaction, sharing living space, and seeing the daily lives of Jews, for the reading public in Poland “knowledge” absorbed from books was largely shaped by anti-Jewish works steeped in ignorance about Jewish literature, religion, and religious practices. As a result, in Poland-Lithuania, unlike in Italy, the German lands, or even France, there were no voices sufficiently knowledgeable about Hebrew texts to challenge anti-Jewish accusations.

Grammars of Memory

Chronicles shaped historical memory. As Heinrich Schmidt has argued, they wrote events “into a future,” making “their presence last.” European chronicles, rooted in biblical and Roman models, formed what Judith Pollmann has called “an archive” of “useful knowledge that was considered to be ‘true.’ ” They recorded “what was memorable and therefore important,” mentioned or even inscribed crucial documents, and narrated power relations.2 Chroniclers had the choice to omit stories or include them, leave them for posterity or doom them to oblivion. Chronicle narratives also supplied morality tales through stories of disorder that always ended with a resolution and return to order.

Scattered among thousands of stories, sometimes from the creation of the world to the contemporary moment, are dozens of seemingly random tales about Jews sometimes with accompanying images. Stories about Jews before the Christian era were grounded in the Bible and other ancient sources, including Josephus, but for the postbiblical period, the major sources were local annals, chronicles, and lore.

Glancing at these chronicles’ indexes, which frequently did not include all the stories in each volume, provides a taste of what European readers could see that Jews historically “did” and what “was done” to them. The most famous, though not the most popular, chronicle of the world by Hartmann Schedel, published in Nuremberg in 1493, includes eleven postbiblical stories about Jews. The nine indexed under the heading “Jews”: “Jews treat irreverently the venerable sacrament in the town of Deckendorff”; “Jews were burned throughout Germany because they poisoned Christian springs”; “Jews were killed and plundered by the inhabitants of Prague”; “Jews were burned by the order of Albert, the Duke of Austria”; “Jews killed a boy named Simon in the city of Trent”; “Jews in these times pierced sacred Eucharist with blood pouring”; “Jews in Nuremberg and other adjacent places were sent to fire”; “a Jew stabbed an image of Christ and blood flowed”; and “a baptized Jew returned to Judaism and was sent to fire.” In short, according to Schedel, Jews kill, desecrate images and the Eucharist, poison wells and springs, and convert to Christianity but often revert to Judaism. In return they are expelled, burned, plundered, and killed.3 The verbs are ominous. These Jewish characters were not the Jews Christians encountered everyday as their neighbors. They were imaginary figures created by Christian writers—dangerous and demonic, enemies who needed to be contained and punished.

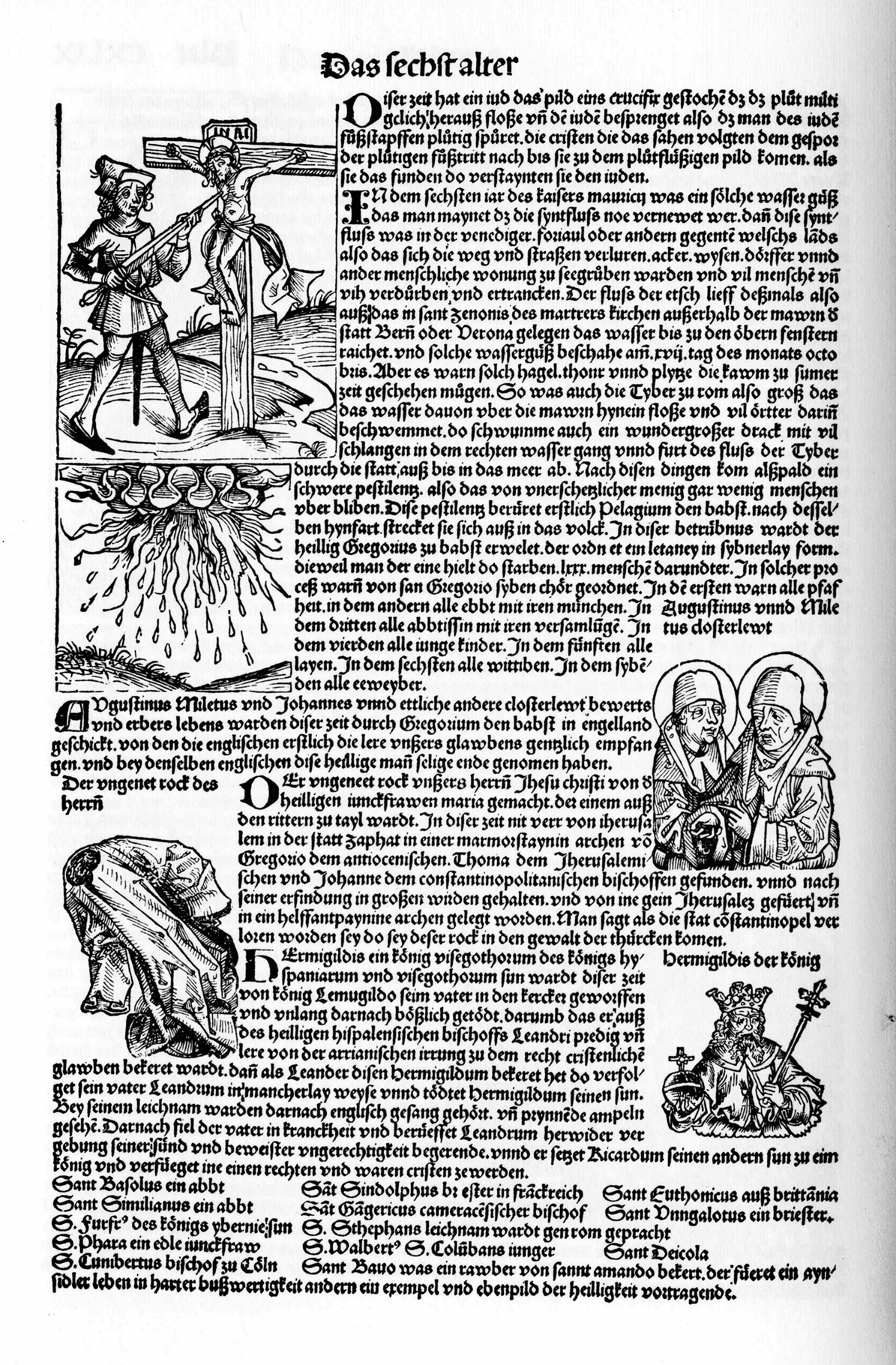

To the stories Schedel added images that stand out on the pages and are larger and more detailed than those accompanying stories not about the Jews. For example, the story of a Jew desecrating a crucifix in the early seventh century is only seven lines long, but the image is the largest on the page (Fig. 4.1), nineteen lines in height.4 Similarly, William of Norwich is mentioned briefly in just one sentence—“Boy William in England was crucified by Jews on Good Friday in the town of Norwich, of whose subsequent wonderful sight one can read,” with an allusion to the story in Vincent de Beauvais’s Speculum historiale—on a page containing stories of prominent Christians: Hildegard of Bingen (seven lines), Gratian (fifteen lines), Peter Lombard (nine lines), and Peter Comestor (eleven lines).5 But the image depicting Jews crucifying William is the largest of all the images on the page, twenty-three lines high (Fig. 1.1). Three stories—the 1298 persecution of Jews by Albert I, the 1337 Deckendorff host desecration together with the persecutions in 1348 during the Black Death, and the 1492 host desecration in Sternberg—are accompanied by a prominent image of Jews being burned, also the largest on the page (Fig. 4.2);6 And of course, there is the iconic image of Simon of Trent, which takes up more than a half-page (Fig. 1.2).

FIG. 4.1 A Jew desecrating a crucifix, Hartmann Schedel, Weltchronik (Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1493), CXLIX verso

FIG. 4.2 Burning Jews, Hartmann Schedel, Weltchronik (Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1493), CCI verso.

Schedel was not the first to depict Jews visually—some of the earliest depictions of Jews in print come from works published in the aftermath of the Trent trial. But he was the first to use such prominent and detailed images in a book in which Jews appeared only as a side topic (the pirated, less splendid versions also included crude copies of the original images).7 But his model of signaling a story through an image would be influential. The publisher of Sebastian Münster’s monumental Cosmographia would later include several recurring images to alert readers to stories about Jews (Fig. 4.3).

Some of the tales about Jews appear only in Schedel’s Liber chronicarum, but he did not start the trend.8 With books becoming available through print, authors increasingly interacted with previous works, creating a veritable chain or, perhaps more accurately, a web of historical memory.9 Schedel’s work was based on material found in earlier printed chronicles, most notably the exceedingly popular Werner Rolevinck’s Fasciculus temporum, which went through nearly forty editions before the author died in 1502, and Jacob Philip Foresti of Bergamo’s Supplementum chronicarum, which first appeared in 1483 in Venice and was likewise extremely popular, with more than twenty editions between 1483 and 1581.10 They in turn had benefited from Vincent de Beauvais’s Speculum historiale, a medieval chronicle published in 1473 and then 1474. (The 1474 edition was used by Bishop Hinderbach of Trent in the trial in Trent.) Some stories found in Schedel had earlier appeared in the works of Vincent de Beauvais, Rolevinck, and sometimes also Foresti. For example, William of Norwich, Richard of Pontoise, and Werner of Bachrach are also in Speculum historiale and in Rolevinck, but the desecration of the crucifix is found in Speculum historiale, Foresti, and some editions of Rolevinck.11

Not surprisingly, in the works of Schedel’s predecessors, postbiblical Jews were also confined to the roles of vicious killers and enemies of Christians, sometimes deceived by a devil; they were, in turn, killed and burned or, if allowed to live, converted. In the 1479 edition of Rolevinck’s Fasciculus temporum, there is a quick succession of these tales concerning Jews: desecration of the crucifix, a Jewish father burning his son to death for having taken communion with Christian children, William of Norwich, Richard of Pontoise, a conversion of a Jew in Toledo, Werner of Bachrach, the expulsion of Jews from France, and burning of Jews for poisoning wells.12

Rolevinck’s and Foresti’s chronicles were translated into many languages, including Italian, German, French, and even Dutch. But not all editions contained the same material. Some included stories that others did not, varying in wording depending on a language, perhaps to reflect different regional sensibilities. Rolevinck’s first official edition of Fasciculus temporum describes events up to 1474, the year of its publication. It was then updated in some, though not all, subsequent editions. Johannes Hinderbach had a copy of the 1477 edition and added to it, by hand, the Trent story.13

FIG. 4.3 Sebastian Münster, Cosmographey oder Beschreibung aller Lander (Basel: Henri Petri, 1567), 180–181. (NYPL, Rare Books and Manuscripts). These images recur both within the volume and in other editions.

The first to introduce the Simon of Trent story into Fasciculus temporum was the Cologne printer Nicolaus Götz in 1478, presumably after the news of the outcome of the investigation in Rome had spread.14 Simon’s story appears as the last event reported just before the colophon, in a short paragraph about “the Blessed Simon” who “was martyred in the city of Trent in year 1475 … three days before Easter,” when, “as is reported, Jews make their unleavened bread with Christian blood.” The infant Simon, the texts says, was captured, crucified, and desanguinated.15 Götz’s edition would begin a trail of transmission in transalpine European editions. With minor spelling adjustments, this version of Simon’s story appeared in editions published in Basel (1482; the 1481 edition has no mention of the story), Strasbourg (1487–1492), Lyon (after 1495), and Paris (1512, 1524).16 But not all editions followed the trail. In Cologne, Heinrich Quentell, the other publisher of the Fasciculus, chose not to include the story in the post-1478 editions, and Simon is not found in Quentell’s 1479 or 1481 versions. Neither did the story enter the 1480 Utrecht Dutch edition or the Geneva French edition of 1495.17 To be sure, these editions of Fasciculus temporum transmitted other horrifying anti-Jewish stories—Rolevinck’s various editions of Fasciculus passed on some ten of about forty such tales found in the early modern chronicles.

In 1480, another version of the Trent story was inserted into a Venice edition of the Fasciculus. Quite tellingly its wording is significantly different, starting a new trajectory. The Venice editions focused on the death of Simon as a reenactment of the passion of Christ and the subsequent punishment of the Jews, and made no mention of the use of blood for matzah.18 A similar wording was then used in Chronicon by Mattia Palmieri of Pisa, which in turn became part of a popular compilation of chronicles that included Eusebius and other authors.19

Yet Schedel’s splendid chronicle did not use the language from Rolevinck’s Fasciculus to describe the Trent affair. Much of his description in the original Latin edition from July 1493 was plagiarized nearly verbatim from Foresti’s Supplementum chronicarum, but not from the first edition, published in 1483. Rather, Schedel drew from one of the later editions printed in 1485, 1486, 1488, or 1492, which also mention the story of a “similar crime” from the town of Motta, appended in Schedel’s chronicle just below the woodcut of Simon; the Motta story is absent in Foresti’s first 1483 edition.20

In 1491, Foresti’s Supplementum chronicarum was also published in Italian, and many more editions followed thereafter. Here, too, the Italian text differs in some significant ways from the earlier Latin version. The Latin version, which had served as a basis for Schedel’s text, explicitly claims that Jews needed Christian blood at Passover for their unleavened bread.21 The Italian editions omit this detail. Instead they state that Jews, who were to celebrate “Passover according to their custom, kidnapped this boy and secretly carried him to a suitable house of one of the Jews named Samuel.”22 After describing Simon’s torments in detail, the text discusses the podestà Giovanni de Salis and the trial during which he ordered Jews tortured “in such a way that one by one (per ordine) Jews described the whole affair.” Out of “the zeal of Christian faith” and a sense of “justice” de Salis then sentenced them all to death. The body of the boy was placed in a church and “performed many miracles;” and, to accommodate the pilgrims, the citizens of Trent built him a new church. The Italian version ends with a sentence about Pope Sixtus IV and his envoy, the bishop of Ventimiglia: “Pope Sixtus at the time in order to be sure of the perfidy and evil of these executed Jews and of the great miracles that the body was performing sent Bishop of Ventimiglia and he found that according to the renown spread it was true.” This sentence offers an interpretation of the events Hinderbach would have been happy to approve. But it does signal uncertainty. The Latin version, even in the post-1491 editions, is silent about the pope and the bishop of Ventimiglia, instead adding a few more words about Simonine miracles. Schedel, for his part, added still more details, among them a mention of Hinderbach, who apparently had studied at the University of Padua together with Schedel’s uncle.23

After the Reformation, the chronicles and the “facts” they presented began to reflect the language and concerns of the splintering religious communities. Although many Catholic and Protestant chroniclers continued to repeat what they found in earlier sources, theological concerns also influenced how the stories about Jews were retold. This post-Reformation trend is especially evident from the second half of the sixteenth century, when Catholic and Protestant scholars turned to history for polemical purposes. The contrast is particularly stark between the Protestant Johannes Sleidanus and his Catholic respondents, among them Laurentius Surius, who inserted Simon of Trent into his lives of saints. For Sleidanus, the history of the Reformation was to inspire rulers to support the Reformation. It was a political history embodying a religious argument that “the Reformation represented a logical event that fulfilled God’s will.”24 In Sleidanus’s vision of history, based on the scheme of four empires from the biblical book of Daniel, the Reformation was “the last stage of the four ages,”25 and the original documents, copiously used throughout, served him to underscore the “union of the sacred and civil state.”26 In that context, Jews were of no concern, except in references to the biblical past.

Sleidanus’s work elicited a strong response from Catholic writers. And there, Jews were quite prominent. The Cologne Carthusian Surius responded with his Commentarius brevis rerum in orbe gestarum—first published in 1566—focusing solely on the events of the sixteenth century. Each new edition of the book was updated to the year of publication. And while most attention was paid to the reformers who were identified with anti-Christ and the devil, and who also appeared in syntax similar to Jews—often “burned,” or committing “crimes”—Jews continued to play an important role in this anti-Protestant polemical history as well. The chronicle includes events such as the 1506 Lisbon massacre, and crucially, given the anti-Protestant context, also reports stories of host desecrations: 1510 in March-Brandenburg, where Jews were tried, tortured, and executed in Berlin (in the process they also confessed to killing a Christian child), and a 1556 trial in the Polish town of Sochaczew, which Surius placed explicitly in the context of the issue of contesting communion under one species.27 Although Surius inserted the story of Simon of Trent in his lives of saints, in this polemical history, he only mentioned blood libel in relation to the confessions from the 1510 trial. This should not be surprising, because in the context of anti-Protestant polemics, blood accusations against Jews had no theological significance. But the stories of host desecration were significant, as were stories of iconoclasm and miracles related to desecration of images. Decades later, Johann Mayr, a priest from the Catholic Bavarian town of Freising, would add to his history of the sixteenth-century stories of the expulsion of Jews from Regensburg in 1519—in its aftermath their synagogue transformed into a church—and a host desecration in Pressburg (today’s Bratislava) in 1591.28

But the quintessential work of Catholic historiography was Cesare Baronio’s Annales ecclesiastici, twelve massive folio volumes published between 1588 and 1607 and covering the first twelve centuries of Christianity. In light of Protestant attacks on the Church as corrupt and disconnected from the ancient church of early Christians—and partly in response to the first Protestant church history, the Magdeburg Centuries—the Annales offered “a comprehensive and critically scrutinized catalogue of documents demonstrating the identity between the ecclesia primitiva and the Roman Church of his own time.” Here, as Stefania Tutino argues, “historical questions were plotted against theological debates,” with an extensive use of primary documents.29

Because Baronio often eschewed earlier chronicles and lore and grounded his work in official records, the Annales provides a more complex representation of Jews’ place in Christian history. Postbiblical Jews of antiquity are palpably present in the first volumes of Baronio’s opus, and the “margins of his book swarm with references to the Code of Maimonides and other Jewish sources.”30 And even in its history of later periods, the work, which was earnestly concerned with avoiding “lies … odious to the God of truth,” contains fewer spurious anti-Jewish stories than earlier chronicles, and focuses more on papal letters and conciliar legislation.31 Church laws concerning Jews were often restrictive, but Baronio also included statements by popes or other prominent churchmen protecting Jews from violence.32 This is best illustrated in his descriptions of the Second Crusade and the events of the 1140s, discussed in volume twelve, where Baronio presented the debate among Christian leaders over the place of Jews in Christianity and the validity of attacking them as enemies of Christianity.33 Baronio turned to Otto Frising’s De gestis Friderici to provide a quote about attacks on Jews by the monk Radulph and his followers. For Baronio, Radulph was a heretic, whose actions Bernard sought to “repress.” And then, Baronio turned to Peter the Venerable and his ambivalent view of Jews, who should not be killed but yet should not go “unpunished” for their “excesses.” Listed among these excesses were not only usury and exploitation of Christians but also a “detestable crime” described by chronicler Robert of Torigni—the story of William of Norwich. Here Baronio used the same vocabulary of earlier chronicles—Jews are attacked, plundered, and killed; they are enemies and killers—but he mitigated this with a discussion of their defense and efforts to repress violence against them. Still, given Baronio’s prominence and his own assertions about the truth, the inclusion stories such as that of William of Norwich gave them additional historical weight.34

But since Baronio’s Annales covered events only until 1198, most anti-Jewish stories of child murders, host desecrations, and others known from earlier chronicles were not included. Those who continued the Annales—Abraham Bzovius, Odorico Rinaldi, and Henri Spondanus—seem to have been more dependent on the legacy of the earlier historical works than was Baronio, who focused more on archival documents he had access to in the Vatican library; and they did include those stories.

Abraham Bzovius (Bzowski), a Polish Dominican and early continuator of the Annales, tried to follow Baronio’s model, including some original sources in the seven additional volumes numbered thirteen and up that brought the Annales to the second half of the sixteenth century in volume twenty. In volume thirteen, covering 1198–1299, readers encountered Jews early, on page three.35 There, under 1198.3, Bzovius discussed their expulsion from France, noting an incident some years earlier when Jews “snatched” a Christian infant in accordance with “the impious custom of this perfidious people.” The child was led to a subterranean cave and crucified “in derision of Christ [in Christi ludibrium].” King Philip Augustus decided to confiscate the Jews’ possessions and expel them from his kingdom. The volume contains thirty “events” related to Jews: miraculous conversions; expulsions (from France and England); host desecrations (1213, 1290, and 1299); blasphemies against Mary (1263); and no fewer than seven stories of child murders. In addition to the one in France, Bzovius noted two in England. One is from 1234 [sic] in Norwich, where “Jews secretly abducted a Christian boy and fed him for a full year, so that during the upcoming Passover” they could crucify him. But they were discovered a few days before committing the crime and “suffered deserved punishment.”36 The second, based on Matthew Paris, is the account of Little Hugh of Lincoln in 1255.37

Although it is perhaps not surprising that Bzovius would have included stories ubiquitous in earlier chronicles, he also utilized other newly available sources and inserted less well-known stories.38 He is one of the few chroniclers to mention the 1236 case from Fulda, which played an important role in setting a legal precedent of imperial protection against anti-Jewish blood accusations, but was unknown beyond obscure medieval monastic sources. Fulda is briefly mentioned in Johannes Trithemius’s chronicle of the Hirschau Abbey published in 1559 and 1601 (Bzovius’s source)39 and more fully in the compilation of local and monastic German chronicles by Christian Wurtisen published in 1585.40 As these medieval monastic chronicles began to be printed, they provided historical “primary source” material for historians like Bzovius and others writing their own annals and introduced hitherto unknown stories about Jews to the broader reading public.

But there were consequences of the dissemination of these medieval stories centuries later. Printed during the early modern period, these medieval chronicles were used in the nineteenth century as historical primary sources for national histories. Monastic chronicles published by Wurtisen and others entered the majestic Monumenta Germaniae Historica, a massive collection of primary sources for German lands that was conceived in 1819, right after the end of the Holy Roman Empire, and began to be published in 1826, becoming a go-to collection of primary sources for German historians. These sources, in turn, helped shape and reinforce the image of Jews in the newly emerging national story. The medieval stories of the horrifying and unusual thus became part of the known historical record, which portrayed Jews in a harmful light, committing horrendous deeds for which they were—as the chroniclers asserted—“justly” punished. Modern readers of the national past were now exposed to repeated stories of massacres and burnings of Jews; of Jews committing suicide rather than converting to Christianity; of Jews poisoning wells, killing Christians, and defiling the sacred. As these historical sources created new national memories in modern times, Jews thus represented did not fit as full members of the emerging nations. Instead, they were a historical enemy within, hateful and hated, a people who kill and are killed.

But Baronio’s model of combining stories from chronicles with papal edicts and church canons provided a platform for a more complex presentation of Jews. Both Abraham Bzovius and Odorico Rinaldi followed it, though unevenly over the course of the additional volumes. Historical documents were plentiful in the volumes covering the thirteenth century, but subsequent volumes became more reliant on traditional sources—chronicles and the increasingly available anti-Jewish works—and thus more anti-Jewish stories entered them.41 Still, both Bzovius and Rinaldi included under years 1200 and 1199 Sicut Iudaeis, the medieval papal constitution protecting Jews. But only Rinaldi included both the 1236 Lachrymabilem Iudaeorum in Regno Francie and the 1247 papal letter against accusing Jews of killing Christians.42 Overall thirty-one papal documents or canons related to Jews were cited verbatim or mentioned by these two continuators of Baronio’s Annales. For the first time, seventeenth-century readers were able to see that Jews were also protected by Christian authorities, and not necessarily always because of bribes. That last issue was addressed apologetically by Rinaldi, who wrote that Mathew Paris’s assertion that Jews bribed their way out of prison and into the protective arms of the pope had given grounds for “calumnies” of corruption against the pope.43

So although many chronicles showed Jews only as usurers, blasphemers, abusers of sacred objects, and killers of Christians acting out of a deep-seated hatred of Christianity, the Catholic Annales ecclesiastici, while still not shying away from spurious stories about Jews, mitigated their impact by including papal letters of protection. Of nearly one hundred stories concerning Jews found in the continuations of Baronio’s Annales by Bzovius and Rinaldi, nearly twenty were of murders (blood libels, ritual crucifixions, or murders of Jewish children for conversion) and eighteen of Eucharistic miracles involving Jews. But there were also the thirty-one papal documents and canons, many of which explicitly condemned violence against Jews. The stories of persecution of Jews were often told as a backdrop to explain papal protection of them. In contrast to earlier chronicles, where multiple stories of persecution of Jews were always justified by stories of their crimes, in the full version of the Annales stories of persecution are frequently countered by acts of protection. Even a casual glance at the index provides a more complex grammar for historical memory.

But that complexity was difficult to transmit. In subsequent abridged versions and in other annals inspired by Baronio, Bzovius, and Rinaldi, this complexity was gone. These “facts,” to use Mary S. Morgan’s concept, did not “travel well.”44 If facts are “settled pieces of knowledge,” the new “facts” about papal protections of Jews presented in the Annales did not fit the cultural knowledge shaped over the previous century or two by ubiquitous stories about Jewish enmity and crimes, which had made it hard to accept that Jews deserved protection. As a result the historical evidence of papal interventions on behalf of Jews was lost from common knowledge and was often challenged when Jews and their protectors furnished such documents. The evidence of papal protection of Jews, especially regarding blood accusations, ran against the established narrative patterns—although published in the Annales but excluded from the more popular abridged editions, it remained in the domain of private elite knowledge.

The “facts” that did travel well and stuck throughout the various editions and epitomes of the annals and other chronicles were the stories that fit the larger narrative and belief system about Jews. Although these stories may have started as local tales or lore, their inclusion in these authoritative chronicles and compilations of primary sources turned them into historical “facts.” Tiberino’s narrative of Simon’s death, for example, became a primary source for the Bollandist Acta Sanctorum, testifying to the verity of Simon’s martyrdom and sainthood. These invented “facts” about Jews then turned into patterns to be used as evidence in a legal context, in trials and legal treatises. Marquardus de Susannis, for example, in his legal treatise De Iudaeis et aliis infidelibus (Of Jews and Other Unfaithful, 1558) turned to chronicles for “facts” to justify expulsions of Jews.45 He mentioned the poisoning of wells, blasphemies, and several examples of murders of children: William of Norwich, along with the other Norwich story from 1234 mentioned in later chronicles, and Simon of Trent. For de Susannis and others, the chronicles were sources of “reliable knowledge” that provided authoritative historical evidence.

Indeed, whereas Catholic scholars may have included stories of host desecrations in their works to boost the validity of the dogma of transubstantiation, stories of Jewish murders and other “crimes” were so entrenched as “facts” among European Christian writers that even Protestant scholars included them in their works, helping embed them deeper in the body of European cultural knowledge about Jews. Sebastian Münster, the Catholic-turned-Protestant scholar, boasted that his Cosmographia “described the people of the whole world, their studies, sects, customs, habits, laws, religions, rites, kingdoms, principalities, commerce, antiquities, lands, creation of lands … and other things if the sort which are celebrated by historians and cosmographers and most of all which are in some way able by their excellence and dignity to come to our knowledge.”46 And yet he included more than a dozen anti-Jewish stories.

That Münster was not immune to such stories has surprised some scholars. He was after all one of the most famous and accomplished Hebraists of his era. He studied not only with fellow Christian scholars, such as Konrad Pellikan and Johannes Reuchlin, but also with Jews, notably Elia Levita. He published a Hebrew and Aramaic grammar, a dictionary, and a translation of the Hebrew Bible into Latin and of the Gospel of Matthew into Hebrew. His importance for the development of Christian Hebraism cannot be overstated.47 And yet, in his Cosmographia, an exquisite example of the historical-topographical genre of the time, he did not shy away from medieval tales about Jews, even from introducing new ones into circulation. For example, Münster’s Cosmographia appears to be one of the earliest European printed works to mention the expulsion of Jews from England48 and only the second to note the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, which appears to have been first mentioned briefly in the Chronicon by Mattia Palmieri of Pisa published in the 1536 edition of Joannes Sichardus’s compilation of various chronicles.49

To be sure Münster did not mindlessly copy earlier chronicles, and his Protestant sensibilities are certainly palpable in his omission of host desecration stories and of language implying sainthood of Christian children said to have been killed by Jews. But these stories nonetheless served Münster, as they did his predecessors, to justify instances of local anti-Jewish violence and persecution. Thus, for example, in his description of France and its kings, Münster briefly noted that “in 1180 there was a great number of Jews in France,” about whom a “rumor” spread that “each year” they kidnapped a Christian child and tormented him on Good Friday. Having learned about it, the king expelled them two years later, in 1182.50 But Münster makes no mention of a shrine to the boy in Paris. The same is true of his description of Simon of Trent. Although, at first glance, the lengthy passage seems to describe Simon’s story dispassionately—even including some nuance by acknowledging that when the Jews’ house was first searched the boy was not found there and by incorporating the Jews’ explanation that the flowing water must have washed Simon’s body into the canal—the text nonetheless gives a detailed description of the tortures Simon was supposedly subjected to and asserts that Jews killed the boy “out of hatred of Christ.” Yet Münster said nothing about Simon’s veneration among Catholics.51 Notably, these stories could have served as potentially anti-Catholic propaganda, but they were not deployed in that way in the Cosmographia. Indeed, although Münster mentioned the story of Jews “martyring” a boy in Berne, which had been inserted in some editions of Rolevinck’s Fasciculus, he did not include the story of the venerated Werner of Bachrach, though he could have noted it in his discussion of Alsace. In Münster’s Cosmographia the stories about Jews are almost always stories of cruelty and disorder, which end with fully justified punishment of the Jews as “authors of all kinds of crimes” either through a judicial process or vigilante violence.52

Münster’s Cosmographia built on both ancient works and the late Renaissance descriptions of the world and peoples. Ptolemy, Strabi, and Pliny provided early models. Christian writers of the late antiquity and the medieval period then reimagined the world within the framework of Christian eschatological chronology, as living in the last of the six ages.53 Later, Renaissance scholars applied this to their vision of the world, which is certainly evident in Hartman Schedel’s Liber chronicarum. His work, though presented as a chronology, also provided a description and visual illustration of the world.54 With the European expansion into the Americas and Africa, European writers began to be interested in descriptions of the world and of customs of peoples inhabiting various lands. The monstrous, tragic, and terrifying became part of the story.

Münster built on this new interest and new body of knowledge. But he also did his own research through traveling and soliciting information from local contacts. It took some eighteen years before the first edition of the Cosmographia saw light in 1544. The book took not only time to prepare but also money, which had to be raised to support the costs of print and production of woodcuts. This may explain why Münster, who “believed that the Hebrew language and Jewish scholarship could be put to the service of Christianity, expanding and refining its body of knowledge,” included more than a dozen anti-Jewish stories in his majestic opus.55 The Cosmographia was a bit of a “pay-to-play” project. Münster appealed to lords and local leaders to provide content and funding: “Cities of the German nation! Do not regret the gulden or two you might spend on a description of your region. Let everyone lend a helping hand to complete a work in which shall be reflected as in a mirror, the entire land of Germany with all its peoples, its cities and its customs.”56 The cities included in the Cosmographia were, unless Münster explicitly noted otherwise, those that paid and provided local information, such as Rufach, whose description and illustrations came from the Protestant theologian and Hebraist Konrad Pellikan and the humanist Konrad Wolfhart.57 Rufach’s description, which appeared first in the 1550 Latin edition, tells of political violence in 1298 (“or according to others 1296”) and its devastation, followed by “calamities” caused by Jews “who in almost all regions conspired to ruin Christians” and who were punished for their crimes. The citizens of Rufach in 1309 burned many of “their Jews, who had a synagogue in the city,” and years later they also killed those who had remained.58 The passage ends with a description of famine and a mention of a painting commemorating it that could still be seen at the time. The stories about Jews in the Cosmographia thus may be those contributing patrons wanted included as part of the description of their lands and cities.

Münster constantly updated his Cosmographia, and some stories, like the Rufach story, appear in some editions but not others.59 But the printer also made aesthetic choices, perhaps in consultation with Münster. The German and Italian editions include images of a crucified child near the story of Richard of Pontoise in 1180 and Simon of Trent (Fig. 4.3). The German and, to a lesser extent, the Latin editions have additional images of bearded and marked Jews to signal stories related to Jews, especially those involving violence and persecution. Visually and in text the Cosmographia reinforces the image of the dangerous, ugly Jew. By crowdsourcing stories, Münster gave to local people voice and the power to determine how they wanted their towns represented to the reading public. He thus captured the way they saw Jews and their place in their local stories. In contrast to Baronio, Bzovius, and Rinaldi, who complicated the representation of Jews in history, Münster allowed for local memory about them to become “facts.” The book’s impact was probably significant, given that it went through some thirty-five editions in less than a century, with an estimated fifty thousand German-language copies in circulation and ten thousand in Latin.60 While Christians may have found in Münster’s Cosmographia a confirmation of their beliefs about Jews, the sixteenth-century Jewish historian Yosef Ha-Kohen used it as a source for his history of Jewish persecution.61

Münster’s Cosmographia exemplifies a genre in which geographic descriptions also included sites and stories associated with specific locales. Georg Braun’s magnificent Civitates orbis terrarum similarly pairs images with texts, and here, too, anti-Jewish tales were included. But unlike Münster, Braun seems to have mentioned only stories linked to existing physical sites. Under Brussels, he described the Basilica of S. Gudula and the associated story of host desecration said to have happened there in 1369.62 In an impressively detailed description of Trent, he added information about the Church of St. Peter’s, “of the Germans,” in which there was “the body of B. Simon” killed by Jews “years ago.”63

A survey of these early modern works, especially the chronicles, reveals a certain pattern. German chronicles and annalistic compilations, in Latin or German, provided European readers with the most vituperative stories about Jews, replicating material taken from earlier works. Rolevinck and Schedel provided most such stories in the early period. They, along with Alfonso de Espina’s Fortalitium fidei, published in at least four editions in the fifteenth century (1471 in Strasburg; 1485 and 1494 in Nuremberg by Anton Koberger, publisher of Schedel’s chronicle; and 1487 in Lyon), provided foundational material for subsequent works. These stories came predominantly from northwestern Europe. And although some documentary annals and chronicles included sources explicitly condemning violence against Jews and thus complicating the prevalent narrative about the place of Jews in the Christian world, only the tales of Jewish cruelty and violence against them appeared repeatedly across the genres. These stories were not inconsequential; they had legal value. Already in the Trent trial, Johannes Hinderbach scoured earlier chronicles and books for stories about Jews to justify the legality of the trial and executions. These early modern printed chronicles would later also be used as evidence in other trials of Jews. But the documentary evidence of protecting Jews was gradually lost from both history and memory, because the works that had a broader reach did not include them.

Strikingly, the earliest printed chronicles about Poland included few such anti-Jewish stories and showed little influence of western European chronicles. An exception is the work by Marcin Kromer, a Polish bishop, diplomat, and chronicler, first published in 1555, which mentions attacks on Jews in “Italy, Germany, [and] France” stemming from a popular belief that Jews poisoned wells.64 Polish chronicles focused on local stories, and by mid-to-late sixteenth century, when these chronicles were published, few anti-Jewish Polish stories had spread. Some Polish chronicles mention privileges granted to Jews by King Casimir the Great, explaining them by his relationship with the Jewess Esther, first mentioned by Jan Długosz in his fifteenth-century chronicle, which itself was only known from manuscripts.65 The chroniclers held that generous privileges were granted to Jews because of Esther’s influence on the king.66 Some Polish chronicles did mention the 1399 legend of host desecration in Poznań, which would become more popular in the late sixteenth and in the seventeenth centuries its dissemination in printed pamphlets.67 Others, among them chronicles by Maciej Miechowita and Marcin Bielski, discussed an attack on Jews in 1406 (or 1407) in Cracow instigated by a sermon given by a priest named Budek, who claimed that the night before, Jews had killed a Christian child, committed abominable things with his blood, and also attacked a priest carrying the consecrated host.68 The story resonated with local Christians, leading to an attack on Jews because, as Bielski claimed, people had grievances against Jews for bribing authorities and escaping justice when they sold stolen objects.

For the most part anti-Jewish stories found in earlier European chronicles did not begin to filter into Poland until the late sixteenth century, when they would enter vernacular explicitly anti-Jewish works. Marcin Bielski’s chronicle of the world, published in 1564 and inspired by Münster’s Cosmographia, is most notable for largely omitting them. For example, although Bielski mentioned the expulsion of Jews from Spain,69 he did not include the story of Jews “martyring” a boy in Berne found in Rolevinck and Münster70 nor the discussion of anti-Jewish persecution that Münster had inserted in the descriptions of Strasburg and Speyer.71 Trent is described in ten words without mentioning Simon: “Trent, city and castle, partly [belonging to] the Duke of Austria, partly to the Bishop of Trent.”72 With the exception of a handful of Polish examples, events related to postbiblical Jews, so ubiquitous in other European chronicles, are virtually nonexistent in Bielski’s description of the world.73

But Bielski did devote a chapter exclusively to Jews.74 The chronicler focused on the Talmud and what he considered its absurd teachings, as well as some Jewish customs, often described erroneously and with derision. After discussing the Jewish holidays, dietary laws, betrothal practices, mourning rites, and ethical teachings that he implied condoned questionable practices, adultery, and even murder, he briefly turned to the accusations that Jews used Christian blood: “As for the [claims] that they drink Christian blood, which they drain from innocent children, as our [writers] claim, I could not verify for sure from baptized Jews; nor regarding their procurement from the Eucharistic wafer [boże ciało], since it is difficult to tell which one is consecrated, which is not.”75 And although Bielski raised doubts about child murders, the use of blood, and host desecrations, he asserted that Jews did indeed “secretly buy children, though not for to murder [them] or for their blood, but to sell them expensively to Turks.” His claim was based on what he apparently had heard from an Armenian. Bielski transformed an accusation found in other books into a new story, which given Poland’s proximity to the Ottoman Empire, seemed plausible. Still his chronicle quite consciously was purged of spurious stories blaming Jews for the deaths of children.

The same cannot be said of a Bohemian chronicle by Václav Hájek of Libočan, Bohemian Chronicle, published first in Czech in 1541 in Prague and then in German in 1596.76 Though, as Zdenek David argues, Hájek was quite familiar with western European chronicles, his chronicle had a distinct local flavor. It contained a staggering forty-six stories about Jews, among them eleven known from other western chronicles, including William of Norwich and Simon of Trent, and new stories pertaining to Bohemia that had appeared nowhere before.77 Here too Jews kill Christians, rob or even burn their churches, poison wells, desecrate hosts, and defraud Christians. As punishment, they are in turn attacked, hanged, burned, or expelled. For example, one of the earliest stories about Jews in Hájek’s chronicle, said to have taken place in 1053, conflates well poisoning and blood accusation.78 It recounts that during a plague when many Christians were dying in smaller towns where Jews lived, no Jew died. At the same time a Jew was caught for attempting to kill a Christian child to use his blood. He confessed to wanting to kill the child for his blood, which was then to be distributed among his family and used for magic. Having learned about these crimes, the duke punished the Jews by burning, whereupon the dying stopped. In Hájek’s work, as in the earlier western European chronicles, Christian violence against Jews is always justified by Jews’ alleged crimes. Hájek’s chronicle fits in the European genre. With these stories he established a pattern of Jewish behavior, using the same action verbs and adjectives, and giving the readers a limited menu of what they could imagine Jews did and what could be done to them.

Regional Epistemologies

Early modern Christian readers seeking information about Jews did not need to resort to leafing through pages of weighty tomes.79 Polemical works about Jews had been published since the earliest days of printing, and by the early sixteenth century publishing patterns emerged, reflecting regional interests and shaping epistemological trajectories. An important early influence was Alfonso de Espina’s Fortalitium fidei, written on the Iberian peninsula before 1461 and published several times north of the Alps. In this work Espina outlined theological questions and provided a long list of anti-Jewish tales about “existential past and present.”80 The theological questions, largely based on earlier polemical works available in Iberia, served as a model for later polemical works, and his anti-Jewish stories became yet another source of “historical” knowledge for those who sought proof of “Jewish cruelties.”81 But whereas de Espina combined two distinct areas of anti-Jewish literature in one volume—theological polemic and spurious anti-Jewish works—later works tended to split these genres according to distinct regional interests. In the German lands and on the Italian peninsula, such literature tended to focus on the polemic against Jews and Judaism, even if the means and topical focus differed. In Poland, in contrast, the theological aspect of anti-Jewish literature was minor, with the predominant emphasis on “Jewish cruelties.”

German lands developed their own regional focus. Traditional anti-Jewish polemic that emphasized theological issues such as the Trinity, the incarnation of Jesus, circumcision, baptism, and other issues did, of course, exist there. A late fifteenth-century work, Pharetra fidei, published in Cologne in the 1490s and republished in Landschut in 1514, offered a polemical dialogue on theological questions between a Jew and a Christian, declaring that “we cannot defeat these vile and rejected Jews except with their own weapons.”82 But in the early modern period there emerged a new genre, marking what R. Po-Chia Hsia regarded as “a shift from theology to folkways, from doctrine to cultural practices,” with books focused on Jewish practices and observances.83 With more than seventy such works published in German or written by Germans, and only a handful authored or published outside the German lands, such “polemical ethnographies” became a predominantly German phenomenon.84

The trial at Trent may have been, as Hsia has argued, an important trigger of interest in Jewish rituals in the German cultural sphere, especially among those who were part of the proceedings, such as Friar Erhard von Pappenheim.85 Von Pappenheim, who had translated a copy of the trial records into German, also wrote a commentary on a Hebrew manuscript of the Haggadah that demonstrates the extent to which the trial tainted his reading of Jewish practices.86 Strikingly, this post-Trent interest in Jewish customs did not take root in the Italian cultural sphere, despite the Trent affair leaving a mark. The “ethnographic” focus remained a German development shaped largely by early sixteenth-century vernacular works by Jewish converts to Christianity and then sustained by Protestant scholars who studied, as Elisheva Carlebach has observed, “Jewish ritual for the purpose of elucidating the original [Christian] practices that had now become objects of serious contention between Christian denominations.”87

The broader Jewish and Christian cultural and political context in German lands may further explain why the “ethnographic” polemic was a German development. For the Ashkenazi Jews of the German lands, the minhag, or custom, was “the core” of their culture, and minhag literature as a genre developed among them from the late eleventh century on.88 By the fifteenth century, the genre was widespread, to the point that custom often served as a basis for some legal decisions. The genre even spread to individuals and individual communities, which recorded their own customs. This literature, as Carlebach has convincingly shown, became a model for the “ethnographic” polemic. In fact, Antonius Margaritha, a Jewish convert and author of one of the most influential polemical works on Jewish observances, first published in 1530, was a product of this cultural milieu. As a cantor’s brother, he knew the importance of “cantorial instructions” when he translated Hebrew prayers for his readers. Although many important rabbis wrote works focusing on Jewish practices, one did not have to be a scholar deeply immersed in rabbinic literature to read or even write such books. Minhag books became a hallmark of secondary elites. It is thus perhaps not surprising that the first such polemical works were penned by Jewish converts who did not display a high level of sophistication in the understanding of the halakhah and rabbinic literature. Victor von Carben and Johannes Pfefferkorn pioneered the genre in the German vernacular with the help of Cologne Dominicans, publishing the earliest such books in the first decade of the sixteenth century. Von Carben’s work, disorganized and laden with errors, did not make as big an impact as the pamphlets penned by Pfefferkorn, who had begun his anti-Jewish crusade in 1507 with the pamphlet Der Juden Spiegel (The Jews’ Mirror), in which he challenged some Jewish beliefs and practices and promoted anti-Jewish policies that would subsequently make it into works by Martin Luther and others.89

Pfefferkorn’s first work on Jewish customs, the 1508 Ich heyss eyn Buchlijn, came with five woodcuts, of which four were full-page images representing scenes of Jewish ceremonies related to the High Holidays. In all of them, Jews are blindfolded as they perform ritual acts such as taschlikh (a symbolic casting off of sins), kapparot (a ritual of atonement), and malkot (a ritual flagellation). These woodcuts were some of the earliest—except for the publications emerging after Trent and the chronicles—visual representations of postbiblical Jews disseminated in Europe. Their goal was unmistakably to highlight the strangeness of Jewish observances.90 In 1509, Pfefferkorn published another booklet, in both German and Latin, in which he promised to offer “a complete explanation of how the blind Jews celebrate their Passover.”91 To be sure, he (or his Dominican handlers) offered a Christological interpretation of Passover, asserted Jews did not understand that the true Passover sacrifice was Christ, and used the text to polemicize against Jews, especially to show that they harbored heretical beliefs. Still, Pfefferkorn did not provide any ammunition for those claiming Jews killed Christian children during Passover for their blood or as a ritual sacrifice. In fact, in the first chapter, he discussed almost matter of factly the preparations for Passover, including making Passover “bread,” the matzah, which he noted was made from special flour—considered sacred—mixed with water in such a way as to avoid fermentation. Pfefferkorn’s book on Passover represented a continuation of his effort to undermine the legal status of Jews in the Holy Roman Empire, but it did not cross the line of providing support for anti-Jewish libels.92

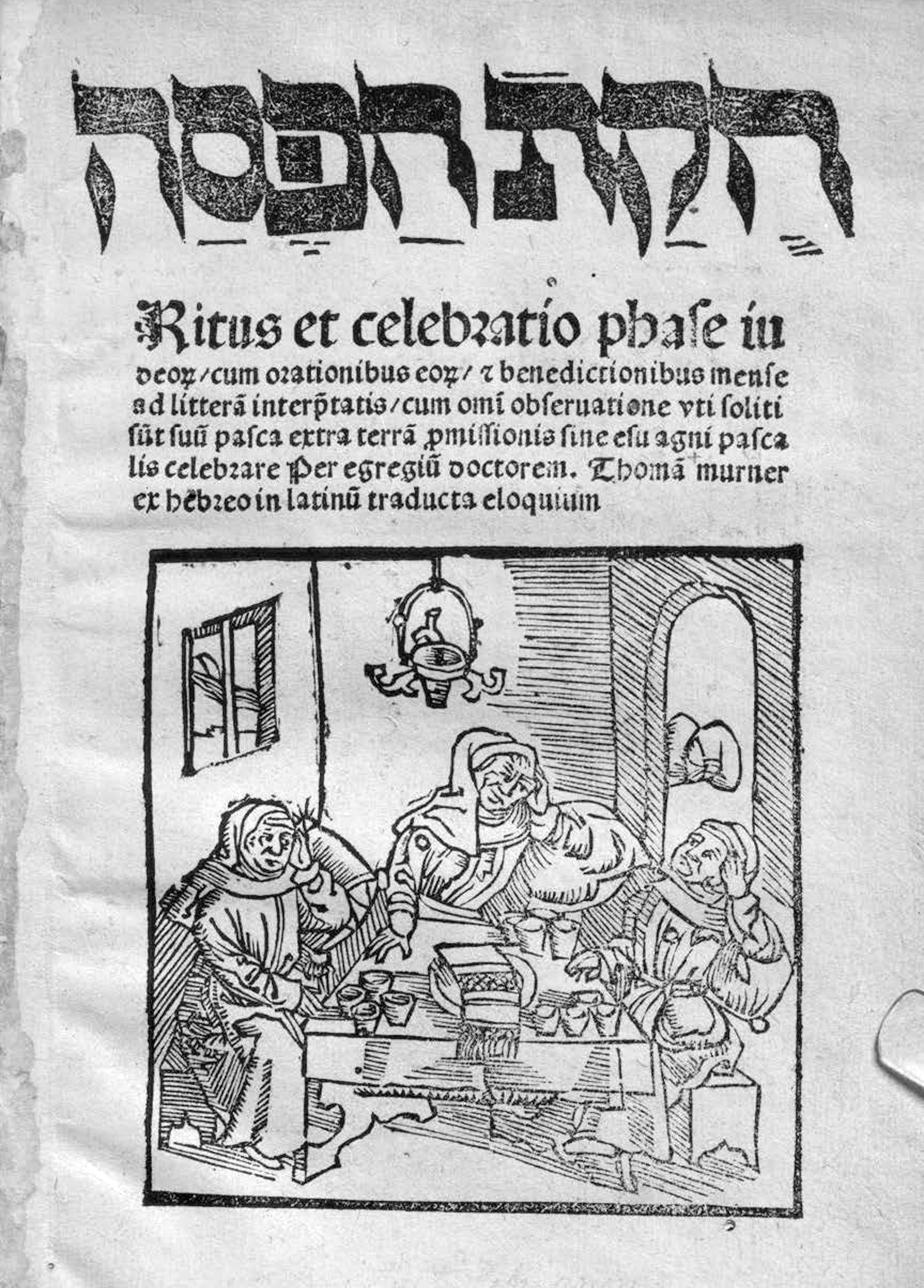

Pfefferkorn’s attacks on Jewish books and ceremonies led to a pushback from Christian scholars. Dragged into this controversy was Johannes Reuchlin, who defended the value of Jewish books and demonstrated Pfefferkorn’s ignorance of Jewish texts.93 In 1512, also as a statement against Pfefferkorn’s attacks on the Passover liturgy, the Franciscan friar Thomas Murner published the Haggadah in a Latin translation; it was the first printed illustrated Haggadah.94 The frontispiece shows three Jews reclining around a table, with matzah at the center covered by a cloth, and four cups of wine in front of each figure—visually symbolizing the four cups of wine drunk during the Passover seder (Fig. 4.4). The remaining images also depict Jews sitting around the table with cups of wine. In contrast to the illustrations in Pfefferkorn’s book, Murner’s Jews are not blindfolded, nor do they have any derogatory features, only the badges visible on the frontispiece.

Yet Murner’s haggadah was still polemical, and not only against Pfefferkorn. The introduction noted that contemporary Jewish celebrations of Passover were not part of biblical observances, but rather an invention during their exile, “observed outside of Jerusalem, against the precepts of Moses.” In fact, the Jews “dare[d] to invent new rituals of Passover,” which Murner considered heretical. Murner’s translation of the Haggadah was also framed within the tradition of Christian polemical interest in Hebrew learning through references to two medieval examples, Paul of Burgos and Nicholas of Lyra. Still, in the context of Pfefferkorn’s crusade against Jewish books, Murner, as Lawrence A. Hoffman has suggested, “hoped to demonstrate that the Haggadah contained nothing worth destroying.”95

As the commentary on the Haggadah by Friar Erhard von Pappenheim makes clear, a discussion of Passover rituals was often an opportunity to indulge in interpretations supporting blood accusations against Jews. Yet neither Murner nor Pfefferkorn went in that direction. In fact, in The Jews’ Mirror, Pfefferkorn addressed the issue directly: “It is a common saying that the Jews have to have Christian blood and also have the monthly flow,” he wrote. “We really put them in the wrong by making such a claim.”96 He saw such accusations as obstacles to Jewish conversion, and although he did not preclude the possibility that some Jews may have killed Christians, he pleaded,

Therefore I ask all faithful Christians to disregard such unfounded talk in order not to give the Jews a reason to be stubborn. It is quite possible that some Jews persecute us and sometimes kill children of Christians because they envy and hate Christ and us. However, they do not do this for the blood but in order to dishonor and harm the parents. For there are bad people in all estates, and although there is once in a while a bad person like that, this does not mean that everyone is of that nature. Therefore, avoid making such accusations so that the Jews will not believe we need them as evidence for our Christian faith, which is clearly without flaws proved by the Holy Scriptures and by miracles.

FIG. 4.4 Thomas Murner, Hukat ha-pesah: ritus et celebratio phase iudeorum (Frankfurt: Beatus Murner, 1512). NYPL Spencer Coll. Ger 1512.

Pfefferkorn’s arguments made their way into Luther’s 1523 pamphlet Jesus Was Born a Jew, in which he expressed hopes for Jewish conversion and pleaded with Christians to treat Jews kindly and not claim that they needed Christian blood “so that they don’t stink.”97 By 1543, in his book On Jews and Their Lies, Luther reembraced the tales of Jews’ need of Christian blood and even mentioned Trent.98

Although the earliest works of this “ethnographic” genre of polemical literature emerged before the Reformation, the genre “reached its mature form” after the publication of a more sophisticated work on the subject in 1530 by another convert to Christianity from a prodigious Jewish family, Antonius Margaritha.99 The genre flourished also in the context of Protestant anti-Catholic polemic and interests, as Protestants began to study “Jewish ritual for the purpose of elucidating the original practices” of early Christians, thereby highlighting the corruption of the Catholic Church.100

Margaritha’s Der gantz Jüdisch Glaub (The Entire Jewish Faith) provides a fuller description of Jewish customs and a translation of Jewish prayers into German.101 Margaritha, recalling earlier Christian polemicists, including Thomas Murner, wanted “to expose Judaism as an unbiblical religion.”102 He was also concerned with what he thought was an unfairly high status of the Jews and sought to undermine it by proposing policy measures that would curb their perceived power and influence. Published just before the 1530 Imperial Diet in Augsburg, Margaritha’s booklet addressed Christian authorities. He hoped that given his status as a son of a rabbi, the book would have an impact.103

In Der gantz Jüdisch Glaub Margaritha argued that Jews harbor a deep-seated hatred of Christians and thus posed a danger to Christian society. According to Elisheva Carlebach, the work framed Jewish rituals as “elements of a deliberately concealed anti-Christian complex,” exposing “the most trivial Jewish everyday behaviors as ‘secrets’ to be probed for clandestine evil intent.”104 It disturbed the emperor, who summoned to Augburg the Jewish leader Josel of Rosheim for a debate with Margaritha. The incident ended with Margaritha’s imprisonment and expulsion from the imperial city.105

Margaritha’s book was hostile to Jews and often inaccurate, but it became an instant bestseller. In the first year of its publication, it was reprinted four times, and then again in 1531, 1544, and 1561. It got another burst of popularity at the end of the seventeenth century, with editions in 1698, 1705, and 1713. Not only did Margaritha’s book shape the genre of polemical “ethnographies,” including later works by Christian scholars, but it also influenced Luther, who used snippets of it in his own writings against the Jews. For example, Margaritha’s claim that, when seeing Christians, Jews mispronounced the greeting “Seyt Gott will komm” as “Sched will komm”—here comes the devil—found its way into Luther’s 1543 book “On Jews and Their Lies,” and then into other polemical anti-Jewish works.106

But for all of Margaritha’s hostility, the book offered nothing to support blood accusations. In fact, in a subtle way, it refuted it. In his description of Passover matzah, Margaritha emphatically stated there was nothing in it—“only flour and water”; not even salt or fat was added.107 Although not all converts unequivocally denied the accusations against Jews, that many did was significant and was noted by some high-profile writers and authorities. Protestant reformer Andreas Osiander in his essay Whether It Was True or Believable that the Jews Strangle Children of Christians and Use Their Blood (written in the aftermath of a trial of Jews in Pösing—now Pezinok, Slovakia—in the kingdom of Hungary in 1529) raised this point explicitly.108 He argued, echoing the bulla aurea from Emperor Frederick II in the aftermath of the violence in Fulda, that baptized Jews who became Christians would have no reason to conceal from Christians what their enemies—the Jews—did. In fact, Ossiander added, Pfefferkorn “and the friars of Cologne” would have been all too happy to reveal “child murders,” had they known about them. Similarly, Paul Ricius, a learned man who also became a Christian, knew nothing about child murders.109 This remained an important point; in 1759, Cardinal Ganganelli would note it in his report on blood accusations. But, as Elisheva Carlebach has pointed out, even when some converts, such as Ernst Ferdinand Hess in 1598, did “report practices in which Jews reportedly used Christian blood for ritual or magical purposes,” the allegations were dismissed as counterproductive falsehoods and an obstacle to the goal of converting Jews to Christianity—a point already raised by Pfefferkorn and repeatedly evoked for centuries.110 One of the most explicit expressions of this view came from Johann Christoph Wagenseil at the beginning of the eighteenth century. “It is certain,” Wagenseil wrote, “that these lies and the untruths accompanying them arouse in them nothing but a hate against Christians, and make them at the same time have a horror of [Christian] religion.… Among those lies (as Luther calls them) the biggest and bitterest which Jews are forced to suffer at the hands of Christians is that they are publicly accused of needing Christian blood.… [B]ecause of those damned lies the Jews have been plagued, tormented, and many thousands of them cruelly executed.”111

The result in German lands was a polyphony of voices about blood accusations. On the one hand, some continued to repeat such stories in chronicles and in reports of new trials. On the other, some, emphatically or just implicitly, denied, for different reasons, the charge that Jews killed Christian children.

The genre of custumals of Jews exploded in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and became increasingly embraced by Christian writers. One of the most successful such books was Johannes Buxtorf’s Synagoga judaica, published just a few years after the convert Ernst Ferdinand Hess published his inflammatory book.112 Synagoga judaica, addressed explicitly to the Christian reader, promised to “consider” with utmost diligence the “great ingratitude, disobedience, and stubbornness” of the Jews through a detailed description of Jewish ceremonies. Buxtorf, a reformed theologian and a professor of Hebrew at the University of Basel, ostensibly wanted to answer the question whether Jews indeed observed “zealously” the laws of Moses. But, in fact, his real purpose was to expose the “unbelief” of the Jews and show to Christians that Jews of his time no longer obeyed biblical laws but instead followed “fables” and other traditions. He wanted to arm Christians with tools against Jewish “unbelief” and help them avoid the “wrath of God.” Like most others, Buxtorf took issue with the Talmud, underscoring that Jews privileged it over the Scriptures. Buxtorf based his description on a wide array of Jewish sources, ranging from the Talmud and the sixteenth-century compilation of Jewish law—the Shulḥan ‘Arukh—to prayer books and Yiddish sources, such as sermons, guidebooks, and minhag books. And yet, despite the undeniable anti-Jewish premise and tone, the descriptions of the ceremonies and practices, mostly based on written sources, were not inaccurate; their goal, to be sure, was polemical but not spurious.

Synagoga judaica was, as Stephen Burnett has argued, “a theological examination of Judaism” through an “ethnographic description” of beliefs and ceremonies.113 Scattered among Buxtorf’s descriptions of Jewish practices are bits of information implicitly refuting blood accusations. For example, Buxtorf provided minute details related to the preparation for and observance of Passover. Discussing the days preceding the festival, he explained the observance and meaning of Shabbat ha-gadol (the Sabbath before Passover), the removal of leaven from the household, and the careful preparation of the Passover matzah: “usually round, full of little holes pierced with a metal tool … made only with clear water.” Without salt or fat, the matzah, Buxtorf added, is quite “unpleasant” to eat.114 A lengthy chapter about the Passover seder gives a step-by-step description, in which Buxtorf noted a few anti-Christian elements of some rituals; for example, he claimed that during the ritual of spilling wine, Jews cursed Christians. Describing in detail the ritual, which so obsessed the Trent interrogators, Buxtorf explained that Jews spilled drops of wine during the recitation of the ten plagues, which were to befall not onto Jews and their houses but “their enemies, evidently Christians.”115 The evening ended with a fourth cup of wine and a blessing based on scriptural passages, Psalms 79:6 and 69: 25: “Pour out Thy wrath upon the nations that know Thee not, and upon the kingdoms that call not upon Thy name,” and “Pour out Thine indignation upon them, and let the fierceness of Thine anger overtake them.” The blessing was in fact a curse “against all peoples who are not Jews,” Buxtorf wrote.116 Though Buxtorf never referred to anti-Jewish accusations, it was clear from his detailed description that no blood, Christian or otherwise, was part of the Passover celebration. In fact, as he showed later when describing dietary practices, no blood was ever part of the Jewish diet. In a section on food, he noted the fastidious avoidance of eating meat and milk together, and the removal of blood from meat.117 So evidently based on Jewish sources, Buxtorf’s exceedingly popular book became an important cultural artifact that subtly debunked blood accusations against Jews by providing a detailed description of Jewish ceremonies.

Some of the works on Jewish ceremonies came with images, a trend begun by Pfefferkorn. Margaritha’s Der gantz Jüdisch Glaub sported illustrations based on Pfefferkorn’s, though smaller and a mirror image of them, suggesting that the artist had Pfefferkorn’s book in front of him. Later books included elaborate scenes of many ceremonies, including Passover and the preparation for it. In the long term, the works demystified Jewish practices. They still presented them as superstitious and absurd. But now these practices were revealed; they could no longer be secret. The 1705 book by Friedrich Albrecht Christiani, Der Jüden Glaube und Aberglaube (On Jewish Faith and Superstition), opened with a demeaning image of Jews with a dog and sow, and included many inflammatory passages and illustrations of some “superstitious” customs, including kapparot and malkot.118 But other plates provided detailed and faithful representations of objects and rituals. Sometimes, as in case of Bernard Picart’s elaborate Cèrèmonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde, the images are exquisite and do not focus just on the absurd.119

Picart’s work differed from “ethnographic” books on Jewish ceremonies produced in the German lands, because his description of Jews was not intended to stand alone: it was one part of a seven-volume massive work on the ceremonies and customs of different religious groups around the world. The book emerged from the early modern genre of travel literature and “ethnographic” descriptions that followed the colonial expansion of Europe, rather than from anti-Jewish polemical instincts, an impetus for the German genre.120 For Picart, Jews were important in the context of the history of religion, and in that sense his work resembled Joannes Boemus’s on the customs of “all people” first published in 1520 in Latin and translated into many languages, including Italian and French, or that of Claude Fleury, whose work on Jewish ceremonies and rites focused on the biblical period.121 Picart’s work fit the new epistemological shift to a focus on witnessing and observation, rather than on textual studies or reports by converts. Even though his descriptions had polemical aspects, his work was not a direct anti-Jewish polemic.122

Picart included several copperplates with ritual objects and scenes to illustrate his elaborate descriptions of Jewish ceremonies. Though not all Picart’s Jewish figures are portrayed in a flattering way—some sport a prominent “Jewish nose”—nonetheless the images are not inflammatory, though not devoid of polemic. Like Pfefferkorn and Margaritha, Picart added in the first 1723 edition of his work illustrations of rituals of Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur and the rest of the High Holidays, but omitted the “bizarre” practices that others emphasized (tashlikh, kapparot, and malkot). An illustration of malkot, the Yom Kippur flagellation practiced among Ashkenazi Jews, was added to the 1741 Paris edition, which copied meticulously Picart’s original plates; but that image was appropriated from August Calmet’s Dictionnaire historique, published also in Paris in 1722.123

Artists made it symbolically known that Christians were now privy to internal Jewish practices. Many illustrations depict Christians gazing or even participating in the ceremonies: for example, in Pfefferkorn’s and Margaritha’s books it is a Christian synagogue attendant, the only figure not blindfolded; in Bernard Picart’s copperplates, centrally located women wear crosses; in Johann Alexander Boener’s depictions of Jews in Fürth, Christians witness Jewish ceremonies outdoor, as they also do in Paul Christian Kirchner’s Jüdisches Ceremoniel and Johann Bodenchatz’s Kirchliche Verfassung.124 The presence of Christians in these illustrations made visible a significant point: it signaled to the readers that Jewish ceremonies, now exposed and witnessed by Christians, were no longer “secret” and concealed. And if in these polemical ethnographies Jews might still be portrayed as blind to the truth of Christianity, as observing “bizarre” and exotic rituals, and even as blaspheming against Christ; and even if they might harbor hostility, indeed hatred, toward Christians—in their actions, Jews just curse: they do not kill. In this light, Jews no longer seemed dangerous. Jews and their rites may have been ridiculed, but those practices were “far different from the murderous rites fantasized in host desecration and ritual murder discourses.”125 With these books, European Christian readers now had tools to learn more about Jews that in a way that countered knowledge passed on through anti-Jewish tales in chronicles, where Jews appeared as secretive, dangerous killers to be murdered and plundered.

Indeed these works did not shy away from the topic of anti-Jewish accusations; blood accusations appeared in them again and again. Pfefferkorn was the first to address it explicitly. Margaritha chose a stealthier way, discussing the rituals of Passover and Passover matzah. But later writers addressed it as well. For example, Friedrich Abrecht Christiani in Der Jüden Glaube und Aberglaube passionately defended Jews against blood accusations, offering “my body and my life” as “a pledge that no Jew should be as bold to have the courage to kidnap and kill a Christian child.”126 Jews, he argued, were “too timid by nature to exercise such a cruel act, especially since they know that they have been subjected to exile among the Christians and under the Christian authorities.” He acknowledged the stories from “two-three hundred years ago,” such as at Trent and elsewhere, but laid the blame on “priests and monks” whose inventions led to persecution and massacres of Jews by the mob. Neither did Bernard Picart skirt the issue, although he was not as unequivocal about it. Despite elaborately describing the Jews’ avoidance of blood, both by biblical commandment and in preparation of meat, in a chapter about “crimes laid to the charge of the Jews” he allowed for ambiguity.127

In contrast to German lands, in Italy there existed only a handful of books devoted to Jewish ceremonies intended for Christian readers. The earliest was Historia dei riti ebraici (History of Jewish Rites) by the Jewish scholar Leone Modena, written ostensibly as a response to Buxtorf’s popular Synagoga judaica and published first in Paris in 1637; it was later republished and translated into other languages a number of times. The French version was included in Picart’s Ceremonies. At the end of the seventeenth century, Giulio Morosini, a convert to Christianity, published a polemical work in which a large part was devoted to Jewish ceremonies, and in 1737, another convert, Paolo Medici, published his response to Modena’s Riti. But in contrast to the Ashkenazi Jews, no indigenous minhag literature seems to have developed among Italian Jews. The minhag books published on the Italian peninsula were Ashkenazi Yiddish, sometimes Yiddish-Italian works, or occasionally Italian translations of Yiddish works, such as the Sefer minhagim published in Venice by Giovanni de Gara in 1589 and republished numerous times thereafter, or even Benjamin Slonik’s guidebook for women, Seder miẓvot nashim (A Book of Women’s Commandments), first published in Yiddish in 1577 in Cracow, then translated into Italian by Jacob Halpron, and published in 1616 in Venice. The Italian edition of Slonik’s guidebook evoked a strong negative response by a Bolognese preacher, Girolamo Allè, who feared that the availability of such books in Italian, combined with the proximity of Jews and Christians, would lead to a “pernicious” Jewish influence on Christians.128 With few works discussing Jewish rites and ceremonies, anti-Jewish polemic on the Italian peninsula was dominated by theological questions shaped early on by Pietro Galatino’s work, De arcanis catholicae veritatis (Mysteries of the Catholic Truth), which itself had been influenced by medieval polemical works.129

If polemical interests by German-speaking Christians, coupled with the Ashkenazi tradition of minhag literature, offer a convincing account of why the “ethnographic” polemical genre was such a German phenomenon, the relative lack of interest in Jewish ceremonies in the Italian context can also be explained by the fact that Italian Christians did not face the same challenges to Christian ritual that Catholics in German lands faced from Protestant attacks during the Reformation. The political situation played a role as well. Because of the frequent expulsions of Jews from German cities and principalities, which may have played a role in creating the minhag literature to preserve local customs in periods of instability, some Christians, including Johannes Reuchlin, feared that Jews, “the bearers of this ancient testimony,” would soon disappear from Europe and thus “doubled their effort” to study the Hebrew language and literature.130 In Italy, the political situation was different. Jews were not expelled; indeed from 1555 their presence was assured, albeit in the increasingly segregated districts that became known as “ghettos.”

On the Italian peninsula, the early polemical literature was driven by Christian Hebraists, mostly Christian Kabbalists, not out of fear of the disappearance of Jews or polemical impulses but because of their interest in Jewish texts as sources of knowledge about Christianity.131 In fact, Pietro Galatino, in his letter to Reuchlin, wrote that his book dealt with “mysteries of the Catholic truth contained in the Talmudic books.”132 This Christian theological interest in Hebrew books was, from the mid-sixteenth century, reinforced by an overt papal policy to censor books and convert Jews. Censorship required competent readers of Hebrew, and although many Jewish converts to Christianity served that role, there were also Christians who studied Hebrew.133 The conversion policy, which mandated regular preaching, in turn effectively created a market for polemical conversionary books, which tended to focus, like medieval polemical works, on validating the “incontestable” truth of Christian dogmas through Jewish texts and demonstrating Jewish “blindness.” For centuries, the Italian anti-Jewish polemic remained by and large theological.

Pietro Galatino’s De arcanis catholicae veritatis, written in defense of Johannes Reuchlin and published in 1518, was of pivotal importance in shaping subsequent Italian polemical literature.134 Twelve chapters not only introduce the readers to basic information about Jewish tradition—such as the concepts of the “written” and “oral” Torah—but also demonstrate “mysteries of Catholic truth” received from “Hebrew books and old scriptures.” For Galatino, as for other Christian Hebraists, Hebrew books were instruments for confirmation of the Christian faith according to hebraica veritas—the Hebrew truth.

Although Galatino was accused of plagiarizing Raymondo Martini’s Pugio fidei, an important thirteenth-century polemical work, it was Galatino’s work that had a demonstrable impact on polemical anti-Jewish works on the Italian peninsula and beyond, because until the seventeenth century, Pugio fidei remained relatively obscure.135 And based on the number of surviving manuscripts, according to Ora Limor, Pugio fidei had “a limited success” also in the medieval period.136 Likely because of that, the book was not brought to print until 1643, when it was first published in Paris. It was followed by three more seventeenth-century editions and one in the eighteenth century.137 By contrast, some other medieval polemical works against Jews—for example, Isadore of Seville’s work—were printed already in the fifteenth century.138

Plagiarized or not, Galatino’s work became quite popular and reached numerous readers across Europe even before the works Galatino had drawn on became available in print. First published in 1518 in Ortona by the Jewish printer Gershom Soncino, De arcanis was then reprinted posthumously in Basel in 1550 and 1561, and in Frankfurt in 1602, 1603, 1612, with a final edition in 1672. It was Galatino’s De arcanis, not Pugio fidei, with which scholars engaged explicitly. For example, Modena refuted De Arcanis in his Hebrew work Magen va-herev, and Christian writers, even opponents of the Kabbalah, referred to De arcanis in their works.139