ADAM CRERAR

The traditional rendering of Ontario as a province unified by the Great War cannot be dismissed as a mere caricature. ‘Rule Brittania’ did indeed reverberate in the streets of Woodstock and Berlin in the hours after Britain’s declaration of war against Germany. Crowds gathered around newspaper bulletin boards for the latest word from Europe. Male clerks, factory workers, miners, lumbermen, and university students lined up at recruiting offices in search of adventure, the opportunity to serve, and a little money in tight times. Veterans of the ill-fated expedition to relieve Gordon at Khartoum trained volunteers in Southampton’s town hall, while in Toronto the cavalry drilled on the snow-dusted exhibition grounds, beneath the eerie scaffolding of idle roller coaster tracks. At railway stations couples embraced fiercely under the muted sounds of brass in the open air. From the pulpit clergymen exhorted men to enlist and comforted the bereaved with thoughts of Christian sacrifice and certain resurrection. Strange new words and the places they evoked – first Ypres, then Passchendaele, later Vimy – entered thoughts and conversations from Copper Cliff to Amherstburg. The newspapers that introduced these words recounted the triumph of individual valour and courage in the mud of France and Flanders as on the football fields of peacetime autumns. At one recruiting rally in Toronto in 1915, 100,000 participants sang ‘Abide with Me,’ their voices rising from the banks of the Don River in the August air.

At Queen’s Park, Tory premier William Hearst and Liberal opposition leader Newton Rowell shelved partisanship on war issues and competed only in their respective pursuit of recruits and donations to war charities. The province sent relief to Belgium and food to the mother country, erected a military hospital in England, and contributed to a fund for the acquisition of machine guns. By 1917 only spending for education outstripped the annual provincial allocations for war-related initiatives, which ultimately totalled almost $10 million. But these expenditures were dwarfed by the $51.5 million donated by individual Ontarians, who together contributed about half of the amount raised for the Canadian Patriotic Fund for soldiers and their families and bought roughly half of the war bonds issued by the federal government in 1917 and 1918. Among many others, the Orangemen of North Huron, St Matthew’s Anglican Church in Ottawa, and Mrs James Young of Galt each donated a machine gun to the troops. Women, excluded from military service because of prevailing conceptions of their essential weakness, spearheaded wartime benevolent activities and made clothes for those overseas; worry, fear, and frustrated ambition powered a murderous clicking of needles in halls and homes across the province.

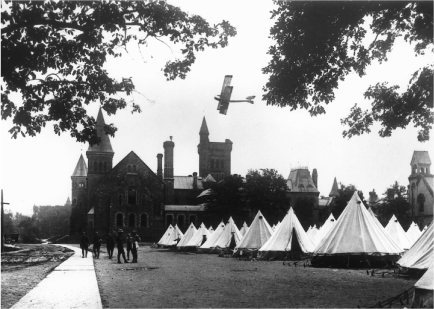

Tents on the main campus of the University of Toronto (ca. 1914), with an aeroplane overhead; the plane is a Jenny JN4, built at Leaside (City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 752)

At universities, scientists trained pilots, produced antitoxins, and counselled victims of shell shock. In the north, miners unearthed iron for shells, sulphur for explosives, zinc and copper for brass bullet casings, and nickel for steel alloys in shells and armour. Employees on the line at Ontario munitions factories ensured that by the third year of the war Canada was producing one-quarter to one-third of the ammunition and half of the shrapnel used by British forces overseas. The public spirit of wartime self-sacrifice and the desire to put barley and rye to good use led the province to introduce prohibition in 1916. Thereafter at the Gooderham distillery in Toronto workers produced acetone for cordite where once the whisky flowed.

As the war stretched into its second year and the reality of casualties and the emergence of well-paying industrial jobs to produce the goods of war made military service less attractive, recruiting leagues from across the province turned to employers, fraternal orders, athletic clubs, and churches for lists of eligible recruits among their employees and members. Women in Blyth and Seaforth issued white feathers of shame to unenlisted men while wearing badges that taunted recipients to ‘Knit or Fight.’ In Berlin, groups of twenty to thirty soldiers seized potential recruits and ‘escorted’ them to the city’s recruiting office. Far from objecting to these coercive measures, municipal councils from Port Arthur to Parkhill, boards of trade in Ottawa and Chatham, and churches, women’s organizations, fraternal societies, business and political clubs, and most of the province’s major anglophone newspapers called for government-enforced enlistment months, or even years, before Prime Minister Borden’s decision in the spring of 1917 to proceed with conscription.

Professionals and businessmen, aided by their allies in academe, the clergy, and the women’s movement, spearheaded the recruiting and conscription campaigns, but the enthusiasm for the war effort was by no means an exclusively middle-class one. Almost four out of every ten Ontario men between the ages of eighteen and forty-five signed up for overseas service before the formal introduction of conscription in October 1917, and many more attempted to enlist only to be turned away for medical reasons. Possibly as many as two-thirds of Toronto men of military age volunteered for service; even if the press gang tactics of recruiters made some of these attempts less than truly voluntary, such a figure nevertheless indicates a remarkable degree of social mobilization for war in the city even prior to the introduction of state compulsion. Furthermore, the vast majority of soldiers were clerks and factory workers, most of whom judged that the Trades and Labour Congress was right in 1915 to characterize the war as ‘the mighty endeavour to secure early and final victory for the cause of freedom and democracy’ and to oppose, two years later, active resistance to conscription over the objections of more radical western delegates. In the federal election held in December 1917 to confirm Borden’s new Union Government and its policy of conscription, Ontario voters handed the prime minister’s candidates seventy-eight of the eighty-two seats at stake. By the time church bells, fire sirens, and factory whistles signalled news of the armistice in November 1918, Ontarians in uniform totalled approximately 240,000 men and women – almost 9 per cent of the population – and over 68,000 of them had been killed or wounded. Communities across the province raised civic memorials to remember the dead and monumental hospitals to care for the blasted minds and bodies of the living.1

In the great narratives of the Canadian experience on the home front during the Great War – of French-English battles over conscription, Maritime and western resentment at Ottawa’s allocation of wartime resources, and conflicts between labour and capital – Ontario stands as the mainstay of a generally conservative anglophone patriotic fervour: the leading source of recruits, industrial hub of the country’s war machine, fount of charity, champion of conscription, and heart of the Union Government and the English Canadian war effort. Ontarians’ determination to wage a war over lands most of them had never previously imagined, let alone looked upon, is indeed both breathtaking and sobering. But the consensus in the province about the justness of the Allied cause can leave the false impression that Ontarians responded homogeneously to the war, marching in lockstep to the rhythm of a common patriotic tune. In fact, the intensity of people’s support for the war, and even their reasons for offering it, varied considerably from group to group, with implications that were anything but predictable. In the heart of British Canada, in the country’s most industrialized province, among the most interesting responses to the war emerged outside the parlours of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE) and beyond earshot of the cheering in public squares.

The western world’s capacity in the Great War to apply technology and organize manpower to the single purpose of obliterating an enemy makes it easy to regard that conflict as an instance of industrialism gone mad. But wars also require food to thrive: without it hungry soldiers relinquish their weapons and famished civilians topple their governments. Since Britain was a net importer of food in peacetime and was isolated from traditional suppliers in central Europe in war, Canada’s pork and wheat arguably contributed as much to the Allied war effort as its shells and bullets. One might not think of Ontario as having been capable of playing an important role in the wartime production of food, but in fact agriculture had remained central to the province’s economy and society in the early twentieth century, even as it continued to industrialize and as a majority of its citizens came to live in towns and cities. More Ontarians worked around barns than in factories in 1914; Ontario’s first war gift to Britain came not in the form of shells or guns – there were none yet to be given – but of 250,000 pounds of flour.2

Ontarians had always romanticized farming in their literature, religion, and politics, but food’s strategic significance in war meant that agricultural labour became idealized as a duty akin to military service. ‘The farmer at work in the field,’ proclaimed Premier Hearst with typical agrarian hyperbole, ‘is doing as much in this crisis as the man who goes to the front.’ The province accordingly increased the number of agricultural advisers in its country districts, provided a thousand tractors for use at cost, and arranged for seed loans for cash-strapped farmers. Determined to make two blades of grass flourish where one had grown before, the provincial Department of Agriculture papered the Ontario countryside with 100,000 flyers and pamphlets in 1917 alone.3

Few Ontarians traded full-time jobs – even with promises of equal pay on the farm – for summers of trudging behind teams and mucking out barns. But for those with flexible summer schedules and the desire to make a little money while serving their country, the idea of farm work held considerable appeal. In 1918, 18,000 to 19,000 high school students – roughly 70 per cent of those enrolled province-wide – signed up as ‘Soldiers of the Soil.’ In the same year, about 2,400 female teachers and university students and married women, known as ‘farmerettes,’ picked fruit and vegetables on the Niagara Peninsula in place of Six Nations men drawn to higher-paying jobs in war industries. Their memoirs suggest that many of those involved in the farm work – bent double in berry fields with special badges sewn on sweat-soaked uniforms – found an opportunity for service and sacrifice otherwise denied to them on account of their sex.

Those unwilling to move to the country were encouraged by federal and provincial officials to plant gardens and even raise pigs in an effort to free up food for soldiers and civilians overseas. Saturday Night humorist Peter Donovan mocked the notion of urban pig-keeping – he conjured up fur-clad society women with pigs on leashes – but through their cultivation of vacant lots across the province, women’s and businessmen’s clubs and baseball and bowling teams raised millions of dollars of produce in 1917 and 1918. However, this wartime gardening frenzy indicated more than participants’ patriotism; it also reflected town and city dwellers’ desire to reduce food costs in a time of high inflation. Among the economizers were the future Group of Seven artists Arthur Lismer and J.E.H. MacDonald, who gardened cooperatively on the latter’s small property in Thornhill. This cultivation provided a degree of household self-sufficiency and inspired one of MacDonald’s most memorable paintings – The Tangled Garden.

That Ontarians responded so effectively to calls for agricultural mobilization suggests how close to its agrarian origins the province remained in the war years. After all, many town and city dwellers themselves had grown up on farms or were only a generation removed from farm families that remained on the land, so they possessed both the skills and the inclination to make this mobilization possible. Clergymen and reporters embraced farming and gardening as prompts to family unity, fitness, and the levelling of class barriers; boys in reform schools who agreed to work on beet or flax farms were deemed to be ‘cured’ as a result of their time in the fields and discharged upon completion of their duties. So, far from seeing the war as promoting the triumph of industrialism, many Ontarians hoped that it would reawaken urban citizens’ appreciation of the value of farming and rural life.4

From the start, enthusiasm for the war effort was not as intense in the country as in the city. The Hamilton Herald complained as early as September 1914 that Ontario farmers were benefiting from high commodity prices boosted by wartime conditions, but failing to meet targets for Patriotic Fund contributions. In the years that followed, urban newspapers continued to flag farmers’ apparent stinginess towards the war charities, the Victory Loan campaign, and the farmerettes. Farmers’ enlistment lagged behind that of the general population as well, and some county councils refused to finance recruiting efforts as substantially as did their urban counterparts. When businessmen, professors, clergymen, and labour leaders founded the Central Ontario branch of the Speakers’ Patriotic League in March 1915, they did so – according to one of the league’s co-founders – because ‘in many parts of the country districts they have not yet come to realize that we are at war.’5

Farmers’ lack of engagement in campaigns to raise money for war charities can be explained in part by their economic circumstances. With their wealth tied up in land, buildings, and animals, most lacked the disposable income upon which the Patriotic Fund and Victory Loan campaigns relied. Furthermore, farming communities’ charity came largely in the form of knitted goods and care packages frequently overlooked by the accountants of patriotism. By contrast, the generosity of urban dwellers was inflated by the large contributions of businesses that suffered no shortfall of income in the overheated wartime economy. Moreover, the Patriotic Fund’s small allowances to soldiers’ families compensated for an urban problem – the loss of income following husbands’ and fathers’ transition from regular employment to military service – and thus had less appeal to farm families, to whom enlistment meant the loss of a pair of male hands. Indeed, clerks and factory workers could leave their employment for military service on the understanding that their families would be supported, at least minimally, by the fund and that in peacetime they could return to their jobs, or ones like them, with few consequences for their future livelihoods. For the unemployed, the option of military pay followed by a return to work in better times was especially appealing. Farmers, on the other hand, wondered whether their properties – their businesses and their homes – could survive their absences.6

Age, the recording practices of military officials, and ethnicity each contributed to the discrepancy between urban and rural rates of enlistment in Ontario. Soldiers tended to be single and in their twenties, but since most Ontario farm owners inherited their properties and worked the land in families, the vast majority of the latter were married and at least in their thirties. Non-inheriting farm boys of military age who had established themselves in non-farm occupations likely remained connected to their home farms in one way or another, but they were not registered as farmers by recruiting officials. Finally, in a conflict about which British-born Canadians were the most enthusiastic on account of their strong identification with the mother country, rural Ontarians tended to be native born. In 1911 the British born represented one-quarter of the men living in cities and towns with populations of 7,000 or greater and fully 31 per cent of men living in Toronto but just one-tenth of those residing in rural southwestern Ontario.7

The separation of farming Ontarians from their urban counterparts was not merely a matter of demography. When E.C. Drury learned of the outbreak of war in the summer of 1914 on his farm north of Barrie, he discussed the news with his wife and then walked out into his fields to read the Globe to his hired men around the binder. No one cheered; no band kicked up dust on the local concession road or startled the livestock. Isolated from the parades, rallies, impressments, and general military presence that imbued public life in the streets of the province’s towns and cities, farmers remained at a remove from the most frenzied expressions of martial fervour in Ontario and were able to retreat from it to the relative quiet of their farmsteads.8

Furthermore, the businessmen and professionals who led the recruiting societies mounted campaigns with a distinctly urban bias. To be sure, calls for young men to fight German barbarism in defence of British liberty and in response to Christian duty could appeal to farm boys and machinists alike. But much recruiting propaganda offered the trials and excitement of war as antidotes to the dangers and boredom of modern urban existence – substitution of athletic soldiering for scrawny clerkdom, the masculine rigours of military life for the pampering of urban middle-class domesticity. Such messages, perhaps popular among male audiences at football and hockey games, had a limited appeal to those in the countryside, who faced no shortage of fresh air, exercise, or proximity to patriarchy.9

The principal issue that set the country against the city in Ontario during the war was conscription. Most urban Ontarians, especially those in the middle class, saw the introduction of conscription in 1917 as a long-overdue measure that ensured that overseas troop strengths would be maintained while shirkers received their due at home. But behind the exuberant newspaper headlines and urban rallies in support of the measure there lay a large and inchoate agrarian population opposed to it. Farmers feared that conscription would exacerbate a farm labour shortage that had been building since 1914, owing to mass enlistment, the drying up of immigration, and the emergence of high-paying employment in war industries that drew prospective labourers away from the countryside to the towns and cities in which it was located. Indeed, the average annual cost in wages of a farmhand nearly doubled in the first three years of the war, from $323.00 to $610.00. The acuteness of these conditions in Ontario – in which there was both a concentration of war industry and a high rate of enlistment – accounts in part for why agrarian concerns about conscription were more intense in the province than in any other part of the country. Despite increased labour costs, Ontario farmers’ concerns about conscription were not rooted in imminent impoverishment. Wartime demand for food precipitated high commodity prices that helped to offset, if not surpass, rising costs and left most farmers in the province better off in 1917 than at the beginning of the war. Ontario farmers’ relative self-sufficiency in food and fuel helped to insulate them from the harshest effects of wartime inflation. Throughout the war farmers continued to drain their fields and settle mortgages, keep levels of acreage under crop and stockholding relatively stable, and run thriving agricultural clubs and Women’s Institutes.10

But conscription threatened to interfere with the free functioning of the family farm economy by removing sons whose labour was essential to the wood-cutting and repairs, seeding and harvesting, and care for livestock that dominated men’s work on the farm. This was true both for sons based permanently at home and for non-inheriting sons. The latter tended to leave their families in stages, departing the farm for schooling and employment but returning periodically to sustain the farm that helped to finance their non-farm ventures and to allow siblings their own opportunities to establish lives elsewhere. It was precisely this reciprocal emigration – which allowed farm families to reconcile the interests of both departing and remaining members – that conscription disrupted by proposing to remove sons from the equation. In the later war years dramatically escalated rhetoric appeared in the farm press about the effects of ‘rural depopulation’ on country districts, not so much because the rate of farm children’s departures was escalating – it was not in any significant way – but because conscription limited farm families’ capacity to negotiate those departures.11

Although most Ontario Liberal MPs initially voted for the Military Service Act in the early summer of 1917, their support for conscription and Borden’s proposal to unite the Conservatives and Liberals in a national wartime government to implement the new policy wavered when they began to hear the reservations of their rural constituents. In the west, the Borden government’s disenfranchising, through the Wartime Elections Act, of tens of thousands of immigrants from enemy countries who had been naturalized since 1902 affected people who for the most part had come to Canada when Laurier was prime minister and tended to vote for his party; without their names on the voters’ lists, western Liberals flocked to the Union Government. In Ontario, however, those disenfranchised represented a much less significant portion of the electorate. Farmers’ anti-conscription attitudes made Liberals’ loyalty to their much-loved chief politically viable, a sentiment that scuttled the prospects for general political union among the federal parties in Canada’s largest province.

Newton Rowell helped to salvage Borden’s plans for Union Government by agreeing to make the jump to Ottawa to serve as the senior Liberal and Ontario minister in the new federal cabinet that was unveiled in October, but the Toronto lawyer’s move failed to assuage the concerns of Ontario farmers. The federal election to confirm the new government, called for mid-December, quickly came to be seen as a referendum on conscription. ‘Shall Canada continue to take her part in the war, and support the men she has sent to the front?’ asked the Orillia Packet, in summing up the views of the government’s urban middle-class supporters; ‘or shall the Dominion quit, and shamefully abandon the brave men who have been battling for civilisation amid the mud and carnage in France and Flanders?’ Anti-conscription rallies in rural Ontario in the first days of the campaign led Union Government strategists to fear that Ontario farmers were preparing to embrace the second of the Packet’s options, so they appointed the great Liberal political organizer and bagman, Clifford Sifton, to spearhead the Ontario campaign. Installed in the less than pastoral setting of Toronto’s King Edward Hotel, Sifton developed a two-pronged strategy to win over the support of the province’s farmers.

First, Sifton persuaded Borden to announce that the local tribunals enforcing conscription would more adequately acknowledge farmers’ need for labour. Then, in a speech to farmers in Dundas three weeks prior to the vote, the minister of militia and defence, General S.C. Mewburn, declared that farmers’ sons would be completely exempt from the Military Service Act. Following further anti-conscription rallies by farmers suspecting an election ruse, the government issued on 3 December one order-in-council confirming Mewburn’s announcement and a second requiring the appointment of agrarian representatives to tribunals to protect the nation’s agricultural interests. A few days later the central appeal judge of the Military Service Act upheld the first of the agricultural exemptions.12

The Union Government’s remarkable accommodation of farmers’ demands was accompanied by vicious attempts to discredit Laurier and the opposition as a group of papist Germanophiles in league with Quebec nationalist and isolationist, Henri Bourassa. Rural Ontarians were primary targets of this propaganda: ‘Slander!’ asserted a fist-shaking son of the soil on one poster. ‘That man is a slanderer who says that the farmers of Ontario will vote with Bourassa, pro-German[s], suppressors of free speech and slackers. Never! They will support Union government.’ As events transpired, Union supporters proved to be no strangers to slander. As the Laurier Liberal candidate in Simcoe North, E.C. Drury found himself subjected to virulent attacks: his opponents called the abstaining and liberal-minded candidate a drunk and a member of the Ku Klux Klan and his Methodist wife a Catholic. In Toronto, members of the Great War Veterans’ Association roughed up Laurier Liberals in the streets. With the exception of the Brockville Recorder and the London Advertiser, local dailies sided with the government and inundated readers with Union propaganda. A few days prior to the election, some local weeklies devoted almost a third of their pages to advertising for the Union government and its local candidates. In North Waterloo, the News Record and the Telegraph failed to publish or even report on any opposing campaign material in the last three and a half weeks of the election.13

Given the virulent rhetoric of the Union forces, their support by leading businessmen and professionals, their control of the press, and their one-sided electoral reforms – including the enfranchisement of female relatives of military personnel overseas and the above-mentioned disenfranchisement of ‘enemy aliens’ – it is hardly startling that the campaign culminated in a huge victory for the government in Ontario. Nor was German- and Franco-Ontarians’ support for Laurier a surprise, given their treatment by the government’s propaganda machine. What is most remarkable is the relative failure of the Union Government in rural southwestern Ontario, where it won just 50.7 per cent of the vote, compared with 62 per cent province wide.14

The meaning of this result is subtle. The government’s problems in this region had little effect on the outcome of the election because its solid support among urban and military voters ensured victory in all but a few ridings. Furthermore, not all of those voters who chose non-government candidates were opposed to the war effort or even to the Military Service Act; although Laurier personally rejected conscription, he insisted only that his candidates agree to a referendum on the matter. Also, agrarian scepticism about the government did not extend to eastern Ontario: evidently the proximity of rural anglophone voters to expanding French-Canadian populations made the former more amenable to the anti-French Catholic rhetoric of the Union campaign.15

Nevertheless it is significant that despite their exemption of farmers’ sons from conscription, shameless smear campaigns against their opponents, manipulation of the ballot, domination of the press, and at least theoretical claim to represent both Liberals and Conservatives, Union candidates captured only a bare majority of voters in the rural south-west. Distanced geographically and emotionally from the public atmosphere of war in the province’s towns and cities, the primarily agrarian residents of the rural heartland of the province remained aloof from the promises and threats of the government. The results, incidentally, did not stem from a regional antipathy to the Tories or passion for Laurier. In the preceding federal election in 1911 Conservatives actually won a greater proportion of votes in the region than Union men did in 1917 – 51.5 per cent of the total – even though they ran on partisan lines and opposed reciprocal trade with the United States, a policy supported by most of the province’s farm leaders.16

That urban workers generally did not share farmers’ lack of enthusiasm for the war effort suggests that the urban-rural divide proved a more crucial determinant of attitudes to the war in Ontario than the gap between haves and have-nots. Despite grievances that surpassed those of farmers – such as the erosion of wages by wartime inflation, shop-floor speed-ups in the munitions and textile industries, government strike-breaking policies and initiatives against radicals, and the failure of the state to impose more than symbolic profits and income taxes – the Union Government captured the support of almost 60 per cent of urban civil voters in southern Ontario, and almost 70 per cent of those in the Toronto ridings. Independent labour candidates won roughly 2 per cent of the provincial vote and merely 8 per cent of the ballots in the ridings they contested. Moreover, although wartime business-labour conflict peaked in 1918, in that year there were about the same number of disputes as in 1913, which in the industrial south involved only 9,155 people. One might attribute these relatively low figures to government repression, but the federal government’s ban on strikes was in place for only the last month of the war, and labour unrest in the workplace and at the ballot box would explode in 1919 despite the government’s escalating repression of the labour movement in the months after the armistice. The complicated history of working-class patriotism in Ontario has yet to be fully explored, but it seems clear that most workers, immersed in the province’s urban culture of war, chose to support the Union Government and stay on the job rather than derail a national enterprise in which they believed. That many profiteering employers failed to show comparable restraint only intensified the post-war reaction.17

Although the Union Government’s exemption of farmers’ sons from conscription did not win the avid support of Ontario farmers, it did bring a halt to their protests and allow them to begin making preparations for the coming agricultural season, a task in which they were encouraged by furious government rhetoric about the importance of increasing production. But while farmers repaired fences and obtained seed in the early spring of 1918, German forces bore down on Allied positions on the Western Front and made all the talk about food somewhat moot. On 19 April Borden announced that, in the light of the German offensive, the terrible casualties it wrought, and the resultant need to reinforce Canadian troops, the government was giving itself the power to cancel all exemptions, including the one for farmers’ sons.18

Most farmers were stunned by the government’s action. A wave of local and regional protest meetings designed to force a reconsideration of the policy culminated in a mass meeting in Ottawa in mid-May, but to no avail. Borden told the gathering of 5,000 farmers – 3,000 from Ontario and 2,000 from Quebec – that his most ‘solemn covenant’ was to Canadian men at the front, not to Canadian farmers, and that the very real possibility of defeat in France made it ‘to say the least, problematical whether any of this production would be made of service to the Allied nations overseas or to [the] men who [were] holding that line.’ In response, the pages of the agrarian press filled with cases of conscripts leaving widowed mothers, ‘imbecile’ fathers, and lone sisters or baby brothers to fend for themselves on otherwise empty farms. In some regions, potential conscripts moved away from highways and into neighbouring fields and woods, where they lived off the goodwill of the surrounding population.19

Prior to May 1918 urban dwellers’ criticism of what many of them regarded as their rural counterparts’ somewhat lackadaisical commitment to enlistment, war charities, and Victory Bonds had been muted, but with Ontario farmers’ rejection of conscription in the Allies’ darkest hour, the gloves were off. Saturday Night’s H.F. Gadsby portrayed the Ottawa protestors as dirty, grass-eating hicks, who smelled of the barnyard and had about as much right to address Parliament as the animals they raised. A number of convictions of anti-conscription farmers accused of violating a federal order prohibiting the expression of anti-war opinions were upheld by the Ontario supreme court, even though the local magistrate in the case had said before the trial that ‘a lot of farmers need[ed] to be jailed,’ and that he was ‘going to put the agitation of the farmers down.’ Tory MPP J.A. Currie even mused publicly about his willingness to use machine guns on the protesting farmers. Queen’s University political economist O.D. Skelton later remarked to farm leader and author W.C. Good that he was ‘astounded by the violence of the anti-farmer sentiment among even educated city people.’ As Skelton’s comment implies, the sentiment that he describes was by no means universal – the Toronto Star even expressed some sympathy for farmers’ labour problems – but it was sufficiently widespread to convince tens of thousands of Ontario farmers that the days of their political accommodation with urban Ontario were over.20

Most farmers were not pacifists: they genuinely believed in government efforts to increase food production in the interests of the war effort and felt that the conscription of their sons served only to undermine those endeavours. In their remonstrance to Parliament in May, the farmers in Ottawa acknowledged that they were appearing ‘at [the] most critical moment of the deadly struggle for the preservation of the liberties of the world.’ But how on earth, they asked, could the esteemed members of the Woodstock Bowling Club and the Arts and Letters Club of Toronto raise more food in their spare time than experienced farmers working full time? While the campaigns to provide urban farm labourers worked reasonably well in the limited and controlled work of berry-picking, they did not always provide farmers with labourers who had the expertise – or the stamina – to conduct even general farm work. W.C. Good, a man renowned for his tremendous capacity for hard work, had been ‘driven almost to death’ by fourteen-hour days in the absence of labour in the fall of 1916. One ‘Soldier of the Soil’ sent out to Good’s Brantford-area farm went AWOL after a day and a half, owing to exhaustion. With farmers struggling to simply maintain levels of production, the Department of Agriculture’s tips on increasing them felt impractical and patronizing. The government-supplied tractors remained expensive and insufficiently reliable to be good investments. A few farmers, like Good, even began questioning the benefits of the greater production campaign itself. Why grow more food if the resulting increase in supply only lowered commodity prices? One could work oneself into the ground and be no further ahead.21

For protesting Ontario farmers the government’s cancellation of exemptions represented a political betrayal. ‘Many farmers accept the principle of conscripting single men with a fairly good grace,’ remarked one Burlington farmer just after the announcement of the change, ‘– but most of them are indignant with the Govt for breaking faith with them after having promised them exemption.’ In calling up farmers’ sons the government broke a critical election promise within five months of its victory and undermined a production policy that had been encouraging farmers to pull out all the stops until just days before the announcement. In explaining their political impotence, many farmers pointed to the dominance of urban businessmen and professionals at Queen’s Park and Parliament Hill and the absence of their own from the corridors of power. Although the pre-war census had declared the province half-rural and half-urban, farmers represented only 18 of 111 provincial MPPs and perhaps as few as 6 MPs from the province. ‘Profiteering urban millionaires have been robbing the farmers of their sons, and robbing them of their representation in Parliament, and they will continue to do so,’ concluded the agrarian Weekly Sun. ‘Isn’t it time farmers organized politically?’22

Those farmers who agreed with the Sun increasingly turned for institutional support to the United Farmers of Ontario (UFO), an agrarian organization founded in 1914 to pursue the social, political, and economic interests of the province’s farmers. The UFO had the support of most existing farmers’ clubs within a few years, but when it became associated with the anti-conscription movement, its membership took off, expanding from 200 clubs and 8,000 members in March 1917 to 615 clubs and 25,000 members by the end of the war. At a convention at Massey Hall in Toronto in early June, 3,000 farmers subscribed $15,000 to fund the creation of a farmers’ paper to ensure non-partisan coverage of farm issues along the lines of the Winnipeg-based Grain Growers’ Guide. By the following month, the Wiarton Canadian Echo was describing the North Bruce United Farmers as part of the ‘rising of a total wave’ of farmers that was creating a ‘transition stage’ in the province’s politics.23

The war emergency and farmers’ fundamental support for the war constrained agrarian political action for the duration – but not completely. When the Hearst Tories refused to nominate a farmer candidate for a provincial by-election scheduled for 24 October in the riding of Manitoulin and provincial Liberals failed to propose any candidate to honour a wartime political truce, the local United Farmers put forward their own man, a Mennonite farmer named Beniah Bowman. The Tories sent Premier Hearst and several heavyweight ministers to Manitoulin, attacked the UFO for causing what they regarded as an unnecessary election, and smeared Bowman as a ‘Mennonite Menace’ not worthy of ‘those priceless privileges which are the heritage of the people of the Anglo-Saxon race’; these privileges were not enumerated, but presumably fair treatment was not among them. Bowman, who ran on a vague platform of ‘equality for all,’ won the election as the farmer candidate with 54 per cent of the vote, a victory that presaged further UFO successes in Ontario North and Huron North over the next few months.24

With the coming of peace, conscription itself ceased to be a central matter in provincial politics. Owing both to local conscription officials’ willingness to repeatedly issue short-term agricultural leave to farmers’ sons and to the happily abrupt end to the war, relatively few farmers were actually conscripted for overseas service. But the war cast a long shadow over Ontario politics in the year following the armistice. Premier Hearst saw his stature among his fellow Conservatives eroded by his wartime policies of prohibition and fiscal restraint on the publicly owned Hydro-Electric Power Commission, which respectively alienated the less temperate members of his party and his most popular minister, Hydro czar Adam Beck. Lacking the experienced Rowell and in any event badly split between pro- and anti-Union factions, the Liberals failed to offer a coherent alternative. Most important, the agrarian political mobilization for political representation that had been sparked by the conscription issue did not fade. The United Farmers movement doubled in size over the next year and precipitated a grassroots campaign that culminated in the stunning election of forty-five UFO MPPs in the provincial election of October 1919. With the support of eleven Labour MPPs, elected by urban voters similarly looking for a new political order commensurate with the country’s wartime sacrifice, the United Farmers formed Canada’s first third-party government. The war had been generally popular, yet within a year of the armistice those who had led the war effort in Ontario were in political exile, and the group at the greatest remove from the conflict now occupied Queen’s Park. The new premier, so recently vilified as a racist and a drunk, was E.C. Drury.25

In 1914 Ontarians’ identification with Britain and the empire was considerably less partial and ambivalent than their associations with urban life. Most were – and, more important, saw themselves as – British subjects. In Ottawa, British traditions and influences shaped both the procedures of government and the neo-Gothic architecture of the parliament buildings themselves. Prior to the war Ontario voters consistently rejected proposals for reciprocal trade with the United States out of respect for the imperial connection, and in their efforts to sort out how Canada could best play a role in the Empire, social reformers and intellectuals felled forests of newsprint. Men served in militia units steeped in British military culture and fought for the mother country in the Boer War; women, banned from the troop ships in that conflict, formed branches of the IODE to support the British cause from home. Across the province, students struggled to memorize important dates and passages from British history and literature, and from 1899 public school patriotism culminated in the speech-making and cadet parades of Empire Day, held on 23 May before the holiday celebration of Queen Victoria’s birthday on the 24th. Postage stamps depicting a map of the world reminded correspondents that Canada’s pink mass was part of the greatest empire that had ever been.26

Soldiers in the trenches, civilians watching, CNE camp, ca. 1914 (City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 966)

Ontarians’ fundamental support for the war effort and identification with British culture in the broadest sense can give a misleading impression of the province’s cultural homogeneity in the early twentieth century. In fact, when Britain committed Canada to war in 1914, almost one-quarter of Ontarians were not, according to the census conducted in 1911, of Scottish, English, Irish, or Welsh descent. Prior to the conflict these Canadians had been regarded by the majority according to a hierarchy of supposedly racial characteristics that favoured peoples from northern and central Europe as fellow ‘nordics’; cast southern and eastern Europeans as problematic citizens who could be assimilated into British-Canadian social and political norms only with considerable effort; and dismissed Blacks, Asians, and Aboriginal peoples as fundamentally incapable of adapting to these norms. Inspired by contemporary theories of nationalism that held racial purity and linguistic uniformity to be prerequisites of national strength, and concerned about the possible erosion of that uniformity by the wave of non-British immigration coming to Canada’s shores in the Laurier years, the federal government increasingly limited the entry of visible minorities, and provincial governments – including that of Ontario – restricted the schooling rights of non-anglophones.27

The Great War’s effects on these relationships were contradictory. On the one hand, the conflict threatened to further isolate minorities within a society whose identity seemed increasingly defined by a war-inspired British-Canadian nationalism. On the other hand, the war provided opportunities for groups previously alienated to demonstrate through their war service their claim to equal citizenship and a place in the main narrative of the Canadian experience. The case of ethnic minorities in the war in Ontario is particularly interesting because, in contrast to the West, where debates about pluralism centred on the assimilation of foreigners, minorities in this province were largely Canadian born. Aboriginal peoples had the greatest claim to original residency, of course, although French communities established on the Detroit River prior to the Conquest actually predated the settlement of the Six Nations on the Grand River following the American Revolution. German-speaking settlers came to Markham township and Waterloo county in the first years of Upper Canada’s existence, and most African-Ontarians in 1914 were descended from men and women who had migrated to the province from the United States to escape slavery prior to emancipation in that country’s Civil War.28 Inasmuch as the war has been seen as a coming of age for Canadian nationalism, what did it mean for these Ontarians, whose attachments to their home communities were at least as strong and long-standing as those of their British-Canadian counterparts?

The pre-war understanding between France and Britain in the face of German expansionism in Europe saw no corresponding entente between French and English on the western side of the Atlantic. In Ontario, the Conservative J.W. Whitney government just prior to the war moved, through a policy known as Regulation 17, to limit French-language education in the public schools to the first two primary years, and to allow this limited instruction only in institutions where French was already being taught. As Patrice Dutil effectively illustrates in chapter 5, the effect of the war was to exacerbate this conflict over language in Ontario schools.

But even as the debate over Regulation 17 became a battleground of the war itself, as French Canadians marched in support of francophone education in the streets of Ottawa and provincial minister of education and Orangeman Howard Ferguson condemned the protests as a ‘national outrage’ that threatened to undermine the foundations of the dominion, there were yet demonstrations of moderation on both sides. Among them were the arguments made in 1917 by two prominent Toronto university professors, C.B. Sissons and George Wrong, for at least some tolerance of French education and the merits of bilingualism. For their part, Franco-Ontarian leaders began to acknowledge the legitimacy of the government’s concern that in a primarily anglophone province all children should become fluent in English. Meanwhile, the actual experiences of francophone students varied widely from region to region: in the province’s oldest French-Canadian communities, in Essex and Kent, French-language schooling was curtailed by order of the region’s Irish Catholic bishop, Michael Fallon, while in northern Ontario French Canadians were so much a part of the region’s social fabric and sufficiently removed from provincial opinion leaders in the south that Regulation 17 was ignored in practice. In the end, despite the tensions it exacerbated, the war did not displace long-standing local relationships between the two linguistic communities.29

Although Irish Catholics like Bishop Fallon shared with the Anglo-Protestant Orange Order a common desire to limit the influence of French Catholics in Ontario society, their feelings for Great Britain were anything but mutual. Most Irish Catholics resented Britain’s colonial policy towards Ireland and might have been expected in 1914 to regard the Union Jack more as symbol of oppression than as an emblem around which to rally in war. Yet despite the British government’s execution of Irish nationalists following the Easter uprising of 1916 and the Canadian government’s virulent anti-Catholic rhetoric in the federal election of the following year, Irish Catholics shared with Protestants the conviction that the Allied war effort represented a crusade for Christianity and the liberty of Canada. Having reconciled Canadian patriotism with continuing opposition to British policies in their home country, Irish Catholics in Toronto enlisted in greater proportions than Protestants and played a leading role in the city’s recruiting and charitable efforts, thus definitively demonstrating their love of country and claim to citizenship on equal terms with their fellow Canadians. The unprecedented support of the Young Men’s Christian Association and the Salvation Army for a campaign in 1918 to provide overseas soldiers with Catholic facilities perhaps best indicates the acceptance of this claim by the Protestant majority. Although sectarian tensions would persist in Ontario for decades, especially in rural parts of the province, this final step in Irish Catholics’ integration into the social fabric of Toronto – a city once known as the Belfast of North America – marked a step forward in the history of Canadian pluralism.30

Unlike Irish Catholics, Blacks in Ontario wholeheartedly embraced both the symbols of British patriotism and the British cause in the war itself. Hamilton newspaper editor George Morton tried to make Canada’s minister of militia, Sam Hughes, comprehend the intensity of his people’s desire to serve. It was rooted in their love for a country that had been ‘their only asylum and place of refuge in the dark days of American slavery,’ he contended, a place of ‘consecrated soil, dedicated to equality, justice, and freedom … under the all-embracing and protecting folds of the Union Jack.’31 Morton’s view was an idealized one – many escaped slaves had not, in fact, found equality and justice north of the border and had returned to the United States following the Civil War – but it affirmed his people’s British citizenship in the face of those who questioned their humanity and was surely no more idealized than the myths of empire that led White Ontarians to Passchendaele and Amiens.

Despite the pleas of Morton and others, Ontario Blacks from large cities and small towns alike were turned away from recruiting stations by the units in which they aspired to serve. Most Whites, blinded by prejudice and the failure of their moral imaginations, supposed that Blacks lacked the requisite intelligence and character to be soldiers. Others thought that training non-Whites to kill Whites was ill advised, whatever the circumstances: it might start a trend. Most White soldiers could not imagine living with and serving alongside Black men. Even when the Toronto journalist J.R.B. Whitney raised forty men and promised 110 more for an all-Black unit, he was rebuffed by Hughes because no commander in Toronto’s military district would take them, and Hughes refused to force integration. Only when the war dragged on and White enlistment began to dry up did the federal government in the late spring of 1916 authorize the formation of a construction battalion of Blacks based in Nova Scotia. Only about 350 Ontario men enlisted in the battalion, possibly in reaction to earlier rebuffs, but more likely because of the general decline in enlistment by this time in the war. Those who joined the battalion were paid the same as Whites conducting similar work and were given their freedom in France, unlike their counterparts in the U.S. army. But Canadian exceptionalism in race relations extended only so far: when a Black sergeant arrested a White enlisted man at a Canadian camp in England a couple of months after the armistice, White Canadian soldiers rioted in protest. Blacks’ service did little to challenge local segregation, which persisted in some communities until the 1960s.32

While African Canadians’ service was discouraged at the start of the war, Aboriginal enlistment was banned outright. The Canadian military justified its policy of racial purity in this instance by casting it as a protective measure: German soldiers would not adhere to the conventions of ‘civilized’ warfare when they encountered Aboriginals on the battlefield. In contrast to the case of Blacks, however, Canadian officials generally winked at this ban and then scrapped it altogether in December 1915, likely because of the well-known history of Natives acting as military allies of the Crown, which made Aboriginal service in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) seem feasible and appropriate. A century after the War of 1812, Native leaders recalled the political and economic advantages that had once accrued to their people in wartime alliances.33

Aboriginal peoples in Ontario embraced the war effort with great enthusiasm, but in ways that confound simple definitions of discrete ‘Native’ and ‘White’ experiences and interests. In the Brock Rangers’ Benefit Society, the women of the Six Nations knitted socks as their White counterparts did in nearby Brantford – Canadian men of all backgrounds required dry feet in the trenches – but they also raised money through the sale of beadwork and other traditional crafts and embroidered a regimental flag that incorporated both British military and Iroquoian clan motifs. Some military leaders proposed that Aboriginals be placed into an all-Native battalion organized around Six Nations recruits, but the plan was dashed by opposition from commanders of other battalions around the province who objected to the proposed diversion of recruits from their own units – and, more important, from non-Six Nations Natives who refused to serve in a battalion dominated by Mohawks. These men enlisted in their local units, alongside their non-Aboriginal neighbours, in great numbers. Among the Nawash at Cape Croker, for example, all men of the age covered by the Military Service Act – twenty to thirty-four – volunteered.34

Aboriginal leaders understandably rejected the view, held by officials at the Department of Indian Affairs, that the exposure of Natives to non-Aboriginal Canadians on the front lines would promote the assimilation of native cultures to a superior Canadian norm, but they were otherwise divided on the implications of military service. The Grand Indian Council of Ontario, the central body of non-Six Nations chiefs in the province, hoped for advances for their people akin to those anticipated by African-Canadian leaders such as Morton and Whitney. ‘We as Indians are at a crucial stage of our lives,’ argued the council president, F.W. Jacobs, in 1917, ‘whilst our young men are at the Front fighting the battles of our Noble King, and our Country, we cannot say that they are fighting for their liberty, freedom and other privileges dear to all nations, for we have none.’ By encouraging enlistment and contributions to war charities and accepting the application of conscription to its peoples, the council strove to demonstrate that ‘Indians, like all humanity are endowed with the same instincts [and the] same capabilities’ as other Canadians. Jacobs enjoined the federal government to give Aboriginals the vote and abolish the treaty system in order to ‘liberate’ his people and allow them to ‘become identified with the peoples of this country and become factors side by side with them in shaping [its] destinies.’ As it happened, the council’s own policies fell short of Jacobs’s ringing appeal to a broader humanity; citing ‘a natural dislike of association with negroes on the part of Indians,’ it successfully lobbied for the transfer of five natives from a predominantly African-Canadian unit at Windsor in 1917.35

The Six Nations Council wanted nothing to do with the Grand Indian Council’s rhetoric of liberal emancipation. Its members saw themselves as the spokesmen of a separate nation, and wanted to be called to war as such – as an ally of the British Crown. When the federal government refused to accommodate this request, the council objected to federal efforts to conscript band members and to hive off reserve lands for veterans’ farm allotments. When the council raised $1,500.00 for ‘patriotic purposes,’ it sent the money directly overseas as a gift to the Crown rather than to the Canadian government or to one of the privately managed war charities. The council’s attitude did not sit well with all on the reserve: some soldiers saw their military service for Canada as compatible with their aboriginal identities and petitioned the federal government to replace the traditional council with an elective one – to no avail. In fact, the council’s position became the ideological rationale for an important post-war Aboriginal association, the Pan-Canadian League of Indians. The league’s founder, Fred O. Loft, a Mohawk lieutenant in the CEF, argued that as a result of wartime service natives had ‘the right to claim and demand more justice and fair play’ – including greater control over band lands and funds and the franchise – though not at the expense of abandoning their heritage or their special status as Aboriginals.36

Although Loft’s league failed to coalesce, it served as a model for future pan-Aboriginal associations. Furthermore the war did promote an unprecedented interaction among Natives from different parts of the province and the country, and wartime relations between Natives and Whites likely gave some among the former a sense of being treated as equals. When the people of Southampton erected a new town hall following the war and dedicated it to those who had served and died in the conflict, for example, they remembered and recognized veterans from the nearby Saugeen band. But such instances of interracial comradeship at personal and local levels proved fleeting, and for Aboriginal integrationists and separationists alike there would be little progress in the years ahead in Native-White relations and little sense of a positive legacy from the first war before the start of the second.37

For those non-British Canadians who did not have deep roots in the province, the cultural lenses through which they perceived the war were often calibrated to long-standing disputes and rivalries in their countries of origin. Most Jews in Ontario in 1914 had migrated from Europe since the turn of the century and had profound social, economic, and cultural associations with friends, family, and communities in the Old World. During the war, Canadian Jews’ desire to promote the cause of their co-religionists overseas led them to initiate extensive fund-raising campaigns, often run by women, for European relief and for the promotion of Jewish settlements in Palestine. These efforts, which culminated in the founding of the Canadian Jewish Congress in March 1919, created a possible conflict with the majority culture: Canadian Jews had little sympathy for Britain’s pogrom-fomenting ally in Russia, especially when Jews had generally thrived in the relatively liberal German and Austro-Hungarian empires. Even so, the Toronto Jewish Council of Women shared in the benevolent work of women across the province and became noted for their initiatives on behalf of the war effort. Furthermore, any potential source of conflict between British-Canadian and Jewish-Canadian agendas was dissipated by the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which, by committing British support to the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, married the cause of British imperialism in the region to the Zionist hope for a Jewish state. News of the British policy prompted huge rallies of Jews in the streets of Toronto and other Canadian cities and sparked interest among Jews in the CEF about serving in a 5,000–man strong all-Jewish legion under British command in Palestine. Unfortunately, the commonality of interest implied by the Balfour Declaration was not fully manifested in practice: four Toronto men in the group of 300 Canadian Jews who joined the new unit were court-martialled for protesting against the legion’s anti-Semitic practices. Although the decisions were later reversed on appeal, they suggest the limited capacity of temporary circumstances, even those as dramatic as the ones emerging in wartime, to dislodge long-term prejudices.38

While Jews’ aspirations were ultimately compatible with those of British Canadians in the war, the same was not the case for Finnish Canadians. Many Finns had been socialists in their home country and had found nothing in the rough conditions of Ontario’s forests, mines, and factories to lead them to abandon their beliefs and vote for the Conservative party. Socialist community halls in places such as Toronto, Copper Cliff, and Port Arthur provided immigrants with social services and a sense of belonging that eased the adjustment to their new society. These beliefs and practices, regarded sceptically by the majority culture in peacetime, became doubly suspect during the war. First, many Ontario Finns opposed Britain’s alliance with czarist Russia, the primary impediment to Finnish independence. Then, the successful Russian Revolution in 1917 and Red Finns’ attempts to emulate it brought Ontario Finns’ socialism into disrepute. When the federal government moved to shut down potentially revolutionary organizations in the last months of the war, the Finnish Socialist Organization of Canada was among them. Although socialist Finns were allowed to reconstitute themselves after the war, their movement had been significantly tainted by the brush of radicalism as a result of the ban, and many Finns thereafter eschewed radical politics in favour of more conservative institutions that sought to win the acceptance of the broader Canadian community.39

During the war itself, however, the people most at risk of harassment were of course those whose ethnicity seemed to associate them with the enemy. Germans, Austrians, and Turks might be loyal to king and country, some thought, but to which ones? The federal government quietly encouraged unnaturalized Canadians – those who had not yet become British subjects – from enemy nations to emigrate to the United States, at least for the duration of the war, and obliged those who remained to register with local officials, surrender their firearms, and make regular reports to authorities. Those who threatened the security of the country or lacked the resources to care for themselves were subject to internment.40

Prior to the war, few perceived that German Ontarians could be regarded as enemies of Canada. Most, after all, had been born in Ontario and had roots in the province extending back to a time when ‘Germany’ itself existed only in the feverish dreams of nationalist intellectuals. Furthermore, the pseudo-scientific gradations of the social Darwinists classified Germans as racial cousins of the British and thus worthy of the rights and responsibilities of citizenship in Canada. The fact that King George and Kaiser Wilhelm were, in fact, cousins and that the former was descended from the House of Hanover seemed rather apt.

Almost immediately, however, the circumstances of the war undermined German Canadians’ relatively favourable status in Ontario. Accounts, true and false, of German war atrocities – of Germans killing nurses, crucifying soldiers, attacking hospitals, releasing poison gas, and murdering civilians by sinking the Lusitania – inflamed anti-German sentiment across the province, in part because many of the victims were Canadian. Wild reports of enemy action in Ontario itself further exacerbated these feelings. On one day the wary residents of New Liskeard spotted a German airship; on another, Parry Sounders caught wind of a German plot to bomb a Canadian Northern train; on a third, the vigilant citizens of Brockville alerted officials with news of planes winging their way from the U.S. border to Ottawa, having misidentified balloons released by Americans in celebration of 100 years of peace with their northern neighbours. Such rumours of improbable German actions were inflamed by the occasional discovery of an actual plot, as when in the summer of 1915 two German Americans were convicted in Detroit for scheming to destroy public buildings and factories across the river in Windsor and Walkerville.41

Despite the fact that there is no evidence of any German Canadian having been jailed for subversive activities anywhere in the province throughout the course of the war, it is clear that a growing antipathy towards all things German resulted in a dramatic reduction in the rights and freedoms of German Ontarians. Toronto’s city council fired civil servants of German descent and closed the city’s German-Canadian social clubs; its Board of Education purged its ranks of enemy alien teachers, forced others to resign who expressed unconventional views of the causes and course of the war, and even fired janitors and groundskeepers of questionable descent. While their Toronto counterparts were ensuring patriotic shrubbery, the Hamilton school board moved in 1915 to force teachers to reveal their citizenship and testify as to their views on the war.

German Ontarians soon found themselves in untenable positions. At the University of Toronto in September 1914 Professor Paul Wilhelm Mueller came under attack for coming to the defence of his sons, students at Harbord Collegiate, who had criticized their principal for making rabidly anti-German speeches at school assemblies. Mueller was hardly a threat to national security. Although, like many German Canadians, he was not officially naturalized, he was no longer a German citizen, was an alumnus of the University of Toronto, and had been resident in Canada for more than twenty years; his rabble-rousing sons were cadets at Harbord Collegiate. But local newspapers, led by the World and the Telegram, started a campaign to have Mueller and the two other German-born professors at the university dismissed, amid ‘rumours’ that the men were engaging in espionage. ‘If we can’t get university professors of British blood,’ thundered Tory back-bencher Thomas Hook to the cheers of the North Toronto Conservative Club, ‘then let us close the universities.’ Well aware of the university’s dependence on provincial grants, the board of governors asked the professors to take full paid leave to the end of June 1915; conscious of their precarious position, all three had moved on to other posts well before that date. When F.V. Riethdorf, a professor of German at Woodstock College, quit his post to offer his services to the Speakers’ Patriotic League, his demonstration of loyalty was attacked as disingenuous. Claude Macdonell, the Tory MP for Toronto South, objected to someone who ‘look[ed] like a German … [and spoke] with a strong German accent playing such a role’; Riethdorf, he contended, should be seen not as a loyal British subject but as a turncoat whose disloyalty to ‘his people’ made him unfit to be a Canadian. Riethdorf left the league and joined the Canadian Medical Army Corps.42

The most profound wartime challenge to the status of German Canadians in Ontario took place in the city of Berlin and the surrounding region of North Waterloo, where three-quarters of the residents were of German ancestry, local anglophones had tolerated the teaching of German to most pupils in city schools, and the German names of pioneers marked the roads. Although German Berliners were enthusiastic about the war effort – they constituted about half of the soldiers of the local battalion, the 118th, and would consistently meet war bond and charity targets – they were on the defensive from the onset of the conflict. German disappeared from the city’s streets and schools as anglophones objected to the public use of the enemy language and German Canadians sought to demonstrate their loyalty by suppressing overt demonstrations of their culture. As the war stretched on, and especially in the wake of the burning of the Parliament buildings in early 1916 – falsely assumed to be the work of German arsonists – questions began to be raised about the appropriateness of the name ‘Berlin’ for an ostensibly loyal Canadian city. ‘The fact remains,’ argued the chair of the North Waterloo recruiting committee, ‘that Berlin was named after the capital of Prussia and is to-day the capital of the German Empire, whence have emanated the most diabolical crimes and atrocities that have marred the pages of history.’ Proponents of a change also feared that patriotic Canadians would refuse to buy products made in Berlin. Opponents noted that the pages of history revealed that the city’s name could not have honoured an Empire that, at its naming in 1833, had not existed, and that the booming war economy in the city was doing just fine.

Yet German Berliners found it difficult to come to the defence of their city’s name. Few wanted either to convey an impression of disloyalty or to attract the attention of the soldiers of the 118th, some of whom had taken to assaulting those of German descent whose patriotism they questioned. In May 1916 soldiers stole a bust of Kaiser Wilhelm I from the German Concordia Club and later returned to sack the place, despite the fact that the club had contributed almost half of its members to the CEF and had closed its doors for the duration out of respect for the war effort. Authorities refused to press charges in the interests of ‘racial harmony,’ and in the wake of the incident the city council asked the province to authorize a name change.

The Hearst government was not particularly eager to accommodate a modification: it refused two requests from the Berlin council before passing a measure allowing any community to change its name following a majority vote in a referendum. In the bitter campaign that ensued, the 118th, free from worries about prosecution, kept potential opponents of the change away from the polls, and possibly hundreds of voters were disenfranchised on the grounds that they were not officially naturalized citizens, even though they had long voted in elections and in some cases had sent sons to Europe. In the end, corruption and intimidation tipped the scales in favour of the forces for change by a majority of 81 out of over 3,000 votes cast. A second referendum designed to elicit a new name drew so little enthusiasm that only one-third of the original electors bothered to vote. ‘Kitchener,’ added to the ballot at the last moment after the English field marshal of that name was lost in the North Sea just prior to the vote, edged out ‘Brock,’ the defender of Upper Canada in the War of 1812, by just eleven votes. Although over 2,000 petitioners – twice as many as those who voted in the second referendum – pleaded with the premier to consider their charges of electoral fraud in the first vote and to delay any change until after the war, Hearst let the decision stand.

Although the loss of the name of Berlin revealed the vulnerability of German Ontarians in wartime, those in North Waterloo remained in a better position than most of the province’s other minorities. Once the 118th was shipped overseas, shortly after the second referendum, the German majority in the region began to reassert its traditional control over local politics. In the first municipal election after the referenda, in January 1917, the residents of Kitchener elected a full slate of anti-name-change candidates, though the new council declined to attempt to return to the original name in the interests of public order. In the federal election later in that year, voters repelled the Union Government’s xenophobic campaign – even shouting Prime Minister Borden down at a rally – and supported an ex-mayor’s candidacy under the banner of the Laurier Liberals by a two to one margin. In the short term, much bitterness followed this election; one veteran concluded that British Canadians should be cleared out of the riding and the remainder – presumably Germans and Liberal supporters – killed by firing squads or hand grenades. Resourceful Guelph city councillors offered their municipality as a refuge for Kitchener businesses seeking to depart their traitorous riding. But the businesses stayed; despite the loss of the name of its city, the German-Canadian community in the area was sufficiently large and well established, physically and culturally similar to the broader British-Canadian majority, and loyally supportive of the war effort to survive the indignities of the war and to rebuild.43

Ukrainian Canadians lacked German Ontarians’ general prosperity and long-standing presence in the province and were thus more vulnerable to the effects of wartime prejudice. Most were single young men from the western Austro-Hungarian provinces of Galacia and Bukovyna who had come out to Canada at the end of the long pre-war years of prosperity to find their fortunes. A few Ukrainians initially favoured the Austrian cause against Russia in the war because like the Finns they feared a victorious Czar Nicholas II would crush their nationalist aspirations, but most supported Britain once it became involved in the conflict, and some even tried to pass as Russians in order to evade the ban on enemy alien enlistment and fight for their new country.

Just as the vagaries of imperialism transformed Ukrainians into ‘Austrians,’ those of the capitalist economy left many unemployed and destitute in the depression of 1912–13. Municipal councils, fearing social unrest and seeking to avoid heavy outlays for relief payments, called on military officials to use their authority to remove impoverished enemy aliens from their streets. Most of the 8,816 people detained in internment camps – about 6,000 of them were Ukrainian – were from the west, the central destination of such immigrants in better times. The largest single internment in Ontario occurred in the winter of 1914–15, when about 800 Ukrainians were taken from the streets of Fort William and Port Arthur, but dozens of enemy aliens, as they were called, were similarly removed from cities in the south as well. Most ended up in camps in northern Ontario, where they were safely removed from the country’s major cities and forced to toil away in manual labour; the transportation of enemy aliens into the Ontario camps contributed to the doubling of the Ukrainian population in the province in the 1910s. At one of the biggest camps, in Kapuskasing, internees cleared land for an experimental farm; everywhere in the north they faced primitive conditions in a harsh climate that induced health problems ranging from frostbite to tuberculosis. Although only about 1.5 per cent of unnaturalized enemy aliens in the country were interned in this way, the very threat of internment – and the sense of rejection by Canadian society as a whole – was felt by all who were at risk.44

Through its internments, disenfranchising of enemy aliens naturalized since 1902 in the Wartime Elections Act, banning of foreign-language periodicals and radical organizations in the last weeks of the war, and tolerance of many private vigilante actions against minorities, the federal government did not live up to its early promise to treat enemy aliens with ‘fairness and consideration.’45 But then neither did the Canadian public. While most of the federal government’s active repression of minorities was aimed at radicals and recent immigrants, the general British-Canadian public tended to be less discriminating.

One of the sorrier developments of the war was the extent to which British Canadians directed their prejudice in a general way against all immigrants. In Kingston, for example, the city’s Dutch sanitary inspector, a Mr Timmerman, was harassed as an enemy alien by his fellow citizens; to the Kingston Standard’s evident amusement, Timmerman was ‘kept busy denying he was a German.’ In 1915 in Guelph, where the enemy alien population was just 1 per cent of the total, local officials registered about twenty-five Armenians as enemy aliens along with the local population of Turks, even though the Old World animosity between the groups was so great that it would result in the Turkish-led Armenian genocide of the next year. Amid news of the battle of Vimy Ridge in April 1917 about 500 veterans and soldiers marched up Yonge Street in Toronto and then broke up into groups of fifty to attack ‘enemy’ businesses and round up ‘aliens.’ The attacks hurt not only innocent Canadians of enemy descent, but also people originally from allied countries such as Russia, Italy, and Serbia, some neutral Swiss, and some Ukrainian veterans of the CEF who had passed as Russians in order to serve their new country.46

Those who harassed ethnic minorities in Ontario did so out of a combination of war-related animosity and fear of minorities as an economic threat. When most interned enemy aliens were released before the end of 1916, the rationale for the action was less the government’s new-found appreciation of civil rights than its perception of the need for inexpensive labour in war industries. When interned Ukrainians were released from confinement to work at tanneries in Bracebridge, their new co-workers refused to work with them and burned their residence for fear of competition from cheaper labour. Ex-internees were given a similar welcome at the tannery in Acton.47

Given that veterans had faced death at the hands of foreigners overseas at the pay of $1.10 per day, unadjusted to inflation, it is hardly surprising that they were at the forefront of much anti-immigrant activity. What is more intriguing is the way in which their actions dislocated the traditional relationships between ethnicity and power in Ontario society. When veterans attacked the works of the Russell Motor Company in Toronto in April 1917 for employing about ninety former Kapuskasing labourers, the soldiers sent to the scene to restore order were initially sympathetic to the veterans. The state, however, sided with the enemy alien labourers and their employers: six veterans were eventually court-martialled for their roles in the attacks.48

On one August night in the last year of the war soldiers and civilians, ostensibly angry at low rates of enlistment of ‘enemy aliens,’ ransacked a total of fifteen minority-owned restaurants in Toronto, starting with the Greek-owned White City Cafe. On the following night, about 2,000 rioters refocused their wrath on the police, attacking officers and starions out of resentment at the police’s attempts to protect the restaurants. Only the mayor’s threat to read the Riot Act and the sending out of mounted police restored order. In the aftermath of the White City Cafe riots, protestors at public rallies, led by the Great War Veterans’ Association, called for the government to conscript non-enemy aliens and single police officers, send enemy aliens to work farms, and plan after the war to revoke the business licences of aliens – naturalized, enemy, or otherwise – and deport them to their countries of origin. The federal government’s banning of foreign-language periodicals and radical organizations at the end of the war was in part a response to these demands.49 One can recognize that some of the government’s motives for not proceeding further were related to its sympathy for the interests of employers seeking cheap labour – not the noblest of motivations, to be sure – and still be grateful that the complete platform of the veterans was not enacted.