I can hardly await the time when the boy will … get to Italy, …. There the very stones have ears, while here they eat lentils and pig’s ears.

—Zelter 1

Succumbing to Wanderlust, Felix yearned to depart for Italy, though he first celebrated his twenty-first birthday with panache: a military band serenaded him, and Heinrich Beer presented a Mozart autograph sketchbook. 2 But some professional concerns intruded. At the beginning of 1830, the University of Berlin created a new professorship in music for Felix. 3 Declining the honor, he advocated for Marx, who won the position later that year; Felix also refused an invitation to conduct again the St. Matthew Passion.

Meanwhile the Zwölf Lieder , Op. 9, and Reformation Symphony occupied his creative energies. Fanny had begun assembling Felix’s second song collection while he was in Scotland, and by February he was composing the last few Lieder. Like Op. 8, Op. 9 appeared in two Hefte of six songs each, now bearing titles, Der Jüngling (The Youth ) and Das Mädchen (The Maiden ), which superimposed on the opus a topical organization, though the texts sprang from several poets, including Heine and Uhland, and the composer’s friends Devrient, Droysen, and Klingemann. Felix expended some effort on the musical coherence of the opus. Thus, Geständniss (Confession , No. 2) begins by glossing the opening bars of Frage (No. 1) in the same key, A major ( ex. 8.1 and p. 176, ex. 6.7 ). Nos. 3 and 4 (Wartend and Im Frühling ) move to B minor and D major, but retain the motivic kernel of Nos. 1 and 2, now rearranged and rhythmically modified. The six Lieder of Der Jüngling , all in sharp keys, reflect a male perspective: in Nos. 1 and 2, the protagonist addresses his lover; in Nos. 4 and 5, springtime and autumn arouse and subdue his passions; and in the barcarolle-like No. 6, he departs from the land of youth and its painful memories. Here the composer’s persona asserts itself, as Felix, about to set out on life’s journey, begins his song by alluding in the bass to the submerged opening of Meeresstille ( ex. 8.2 and p. 189).

Ex. 8.1 : Mendelssohn, Geständniss , Op. 9 No. 2 (1830)

If Felix is the youth, then the romanticized maiden of the second Heft is Fanny. Not coincidentally, three of her Lieder appear here, again without attribution: Sehnsucht (No. 7), the female counterpart to the male longing in the first half; Verlust (No. 10), in which the maiden’s lover breaks her heart (Fanny depicts the loss by ending with an inconclusive half cadence); and Die Nonne (No. 12), in which a maiden, mourning her paramour’s death, expires in a convent garden before an image of Mary. For the remaining Lieder Felix assumes the feminine perspective: No. 8, a spring song, is a counterpart to No. 4, while No. 11, Entsagung (Renunciation ), set to pious verses of Droysen, was inspired by his sister’s confirmation. No. 9 (Ferne , Distance ), also on a poem of Droysen, refers to a separation and reunion; indeed, near the end, the song pauses on the phrase, wenn du heimkehrst (“when you return home”), again linking the cycle to recent events in the siblings’ lives.

Ex. 8.2 : Mendelssohn, Scheidend , Op. 9 No. 6 (1830)

In contrast, Felix composed the Reformation Symphony for a public event, the tercentenary of the Augsburg Confession (June 25, 1530), at which Melanchthon had presented Charles V a summary of the new Lutheran faith. Three hundred years later Frederick William III appropriated the Confession to advance the union of Prussian Lutherans and Calvinists into an Evangelical Church. 4 Quite likely Felix conceived his symphony in 1829 for the anniversary, but for reasons unclear its premiere did not occur until 1832, and in 1838 he renounced it as “youthful juvenilia .” 5 Thirty years later, in 1868, it appeared as Op. 107, and like Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony, published the year before, entered the canon in the closing decades of the nineteenth century.

Felix described the work as his Kirchensinfonie ; indeed, its programmatic narrative, culminating in the triumph of the Reformation, is not difficult to decipher. Thus, the introduction to the first movement simulates Catholic polyphony through imitative counterpoint based upon the “Jupiter” motive, in its pre-Mozartean incarnation as a psalm intonation ( ex. 8.3a ). The rising entries form a point of imitation in Palestrinian stile antico . Chordal wind fanfares, the first suggestion of conflict, answer the counterpoint, but then Felix inserts a second telltale motive—the “Dresden Amen,” a response used in Catholic regions of Germany and associated with the Holy Spirit ( ex. 8.3b ). The simple, scalelike ascent in high, ethereal strings later figured in Wagner’s Parsifal and precipitated a controversy in 1888 when the American musician Percy Goetschius asserted Wagner derived the idea from Mendelssohn. How Felix happened upon the response in 1830 remains a mystery, though he knew at least two composers who had employed it, Carl Loewe and Louis Spohr. 6

The first movement proceeds with a fiery Allegro in D minor rent by militant fanfares to suggest the spiritual strife. The extramusical significance of the second movement, a light Scherzo in B ♭ major, remains unclear, 7 though the introversion of the Andante in G minor would seem to owe its inspiration to Felix’s Dürer Cantata of 1828 (see p. 186) and probably does not suggest, as Paul Jourdan has hypothesized, a “rare reflection by Mendelssohn on his Jewish ancestry.” 8 The finale is a symphonic fantasy on the Lutheran chorale Ein’ feste Burg ist unser Gott (“A mighty fortress is our God”). Introduced by a solo flute, the melody is soon buttressed by winds and brass, symbolizing collective, congregational worship. A transition leads to an Allegro that revisits the idea of spiritual division through a dissonant fugato. Ultimately the symphony concludes with triumphant chorale strains for the entire orchestra.

Ex. 8.3a: Mendelssohn, Symphony No. 5 (Reformation , Op. 107, 1830), First Movement

Ex. 8.3b: Mendelssohn, Symphony No. 5 (Reformation , Op. 107, 1830), First Movement

In 1830 Felix was still under the sway of A. B. Marx: essentially, the symphony was an attempt to render the Reformation as a Marxian Grundidee by resorting to Beethovenian models. The sharply differentiated music for the two faiths—Catholic polyphony versus the Protestant chorale—betrays the influence of one of Marx’s favorite scores, Beethoven’s Wellington’s Victory , with its musical opposition of French and English forces. There is compelling evidence Felix was also responding to the Ninth Symphony, which, like the Reformation , has outer movements in D minor and D major. Felix’s autograph reveals that his finale originally began with a flute recitative leading to the “discovery” of the chorale. 9 Felix deleted the recitative as perhaps too obvious an allusion, but the emergence of the chorale as the goal of a spiritual quest surely owes much to Beethoven’s final symphonic odyssey.

According to Devrient, Felix attempted an unusual experiment in the first movement: notating the score vertically one measure at a time, instead of sketching melodic and bass lines and then filling in the missing parts. Devrient watched the serried movement progress “like an immense mosaic.” 10 By late March 1830 Felix had reached the third movement but was distracted when Rebecka contracted the measles. Even though she was quarantined, Felix too fell ill and postponed his journey. By April 9 he was well enough to begin the finale; then, on May 1, he paused to compose a small cycle of four Lieder. 11 Their poet remains unknown, but their subject—the journey from childhood to manhood—recalls Op. 9 No. 6, as if Droysen had a hand in crafting the verses. The overarching theme of lovers separated and reunited revives somewhat the sentimental program of Carl Maria von Weber’s Konzertstück (see p. 80), but now from a masculine point of view. In Der Tag , the innocent child becomes a youth and falls in love; after an arduous ride on his steed (Reiterlied ), he arrives at a castle and searches for his lover in the woods. Summoned to serve his country, he bids her farewell in Abschied , and then, after returning from the ravages of war a common beggar (Der Bettler ), seeks reunion with her. “Recognize me,” he entreats her, and Felix’s music responds with the ending of Der Tag , unifying the Lieder and hinting at what he might have achieved in a more ambitious song cycle.

On May 13, having dated the autograph of the Reformation Symphony the previous day, Felix departed with his father. In Dessau he saw Wilhelm Müller’s widow and visited the Kapellmeister J. F. Schneider. Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt was “wildly” rehearsed, and at a party Felix played trios with Schubring and W. K. Rust and improvised on the opening of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. 12 In Leipzig Felix established ties with the leading music houses, Breitkopf & Härtel and F. Hofmeister, while Abraham returned to Berlin. Through Heinrich Marschner, immersed in an opera on Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe , Felix sold the String Quartet, Op. 13, to Breitkopf & Härtel; its sibling, Op. 12, to Hofmeister, who informed the astonished composer that a pirated edition of the First Symphony, Op. 11, was already circulating in Leipzig. 13 But in a precopyright age, Felix was powerless to stop the theft and instead laid plans with Heinrich Dorn, director of the Leipzig opera, to premiere the Reformation Symphony on June 1. Felix also examined Bach manuscripts before traveling to Weimar on May 21.

Sensing he would not see the Nestor of poets again, Felix extended his stay to two weeks and asked Goethe to use the familiar du . There were discussions about Schiller, Scott, Hugo, Stendhal, and Hegel, and Goethe gave his friend a bifolio from the second part of Faust 14 and commissioned a crayon sketch of the composer, which Felix found “very like, but also rather sulky.” 15 Felix played almost daily on Goethe’s Viennese Streicher piano. During these structured sessions Felix presented compositions by “canonical” composers in chronological order. The octogenarian listened intently from a dark corner, his eyes occasionally “flashing fire” like a Jupiter tonans (“thundering Jupiter”). But when Felix approached modern times by playing Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, Goethe reacted, “That causes no emotion; it is only astonishing and grandiose.” 16

In Weimar Felix revised the Reformation Symphony and dispatched a copy to Leipzig—too late, for Dorn had already cancelled the performance. Felix also flirted with the ladies, composed for Ottilie von Goethe a tender Andante in A major, 17 and contributed to a new journal titled Chaos . Launched under Ottilie’s editorship in September 1829, Chaos was a weekly publication comprising madcap poems, letters, and riddles, appearing anonymously or with pseudonyms, solicited from Goethe’s circle. 18 Felix now took his place among Chamisso, Holtei, de la Motte Fouqué, Thomas Carlyle, and Thackeray. To the first series (1830) Felix contributed two letters. 19 One, signed “Felix,” purports to be by a visitor of the Rheinfall near Schaffhausen. The other, signed “Sophie Stbrn.,” caused much merriment in Weimar, where readers were unable to identify the author. Here a zealous aunt admonishes her niece against visiting the town, for it has been overrun by the Engländer John Knox, Rob Roy, and Jonathan Swift, all contemplating harmful deeds. Felix also exchanged humorous verses with his lady friends and composed Chaoslieder , including the folksonglike Lieblingsplätzchen (Op. 99 No.3), for which he disseminated the misinformation that the text was from the folk anthology Des Knaben Wunderhorn . 20

On June 6 Felix arrived in Munich. The capitol of Bavaria, created upon the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, was developing into a southern German arts center under its Wittelsbach king, Ludwig I. An ardent philhellene, Ludwig embarked upon a massive construction program: the Renaissance-styled Pinakothek to display Flemish and German art; Ludwigskirche, after Byzantine and Romanesque models; and Glyptothek, a marble temple finished in 1830, to exhibit Greek and Roman statuary. The king positioned triumphal arches around the city and recruited celebrated artists to support its rejuvenation. Among them were Peter Cornelius, who adorned the walls of the Glyptothek with murals of Greek mythology, and J. K. Stieler, who specialized in portraits of attractive models. Ludwig had tried unsuccessfully to bring Goethe to Munich; now Felix, armed with letters from the poet, mixed with members of the court, including J. N. Poissl, Intendant of the royal theater and opera. Felix tried the organs of the local churches, appeared with the clarinetist Carl Baermann, and introduced Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata at soirées that prized Kalkbrenner and Field as “classic or learned music.” 21 Through Stieler, who escorted Felix to Munich art galleries, he met the talented fifteen-year-old Josephine Lang (1815–1880), the artist’s goddaughter, who sang Lieder. The encounter encouraged her to pursue composition; she later produced about one hundred and fifty, several of which won acclaim. When Felix departed from Munich, he inscribed a volume of Goethe’s poems with the gentle monition, “Do not read, always sing, and the entire volume will be yours.” 22

In Munich, Felix conceptualized the Scottish Symphony 23 and read Op. 11 with the royal orchestra. Instead of celebrating the Augsburg Confession with the Reformation Symphony, he observed colorful Corpus Christi processions in Catholic Munich. There was another distraction—the pianist prodigy Delphine von Schauroth (1814–1887). The two had met in Paris in 1825, where she had studied with Kalkbrenner. By 1830 she had blossomed into an attractive young woman of seventeen, of a noble but impecunious family. Felix’s pocket diary records frequent meetings. 24 To Rebecka he confided that Delphine was “slim, blond, blue-eyed, with white hands, and somewhat aristocratic”; she possessed a good English piano, which, along with her charms, seduced him into visiting her (Felix’s sisters considered her a potential sister-in-law, and Lea was concerned enough to make inquiries about the Schauroths). 25 They performed a Hummel duet and made a musical exchange.

Ex. 8.4a: Mendelssohn, Rondo Capriccioso , Op. 14 (1830)

Ex. 8.4b: Mendelssohn, Rondo Capriccioso , Op. 14 (1830)

First, Felix revived for her the Etude in E minor (1828) and added a nocturne-like introduction in E major to produce the Rondo capriccioso , Op. 14. 26 A slow movement linked to a bravura finale, this ebullient showpiece later served as a paradigm for Felix’s Capriccio brillant , Op. 22, and Serenade und Allegro giojoso , Op. 43, both for piano and orchestra. Felix diligently covered all traces of the recomposition, adding, as he put it, “sauce and mushrooms.” Thus, he assimilated the characteristic descending fourth of the elfin rondo (E–B) into the lyrical descending phrase of the Andante ( ex. 8.4a, b ), so that the rondo seemingly sprang from the slow movement. Delphine reciprocated by doting one night upon a Lied ohne Worte for Felix. 27 Not coincidentally, it is in E major, as if she intended to replicate the nocturne-like textures of Op. 14 ( ex. 8.5 ). Dated July 21, Delphine’s Lied was preserved by Felix in his autograph album. 28 Finally, early in August he read with her a new piano-duet arrangement of the String Quartet Op. 13.

Ex. 8.5 : Delphine von Schauroth, Lied ohne Worte in E major

As we shall see, from Italy Felix often thought of Delphine, and their relationship deepened upon his return to Munich in 1831.

From Berlin, Felix received worrisome reports about Fanny’s health. Pregnant with Sebastian, she experienced an Unfall on May 24, 1830; 29 her concerned brother sent letters, including one to Lea, to be shared with Fanny if the baby survived. Resorting to music, he concluded a letter on June 14 with an Andante in A major, expressing what he prayed God would grant her. 30 Its dotted rhythms and key recall the style of Frage , Op. 9 No. 1, and a cadence near the end reproduces the close of Geständniss , Op. 9 No. 2; Felix endeavored from afar to comfort the bedridden Fanny with the familiar music of Der Jüngling . Sebastian was born prematurely on June 16, sickly and frail, and not expected to survive. He received the names Sebastian Ludwig Felix, after the three principal composers in Fanny’s pantheon, and at his christening the sculptor C. D. Rauch and Zelter, who stood in for Felix, served as godparents. 31 From Munich Felix sent a congratulatory Lied ohne Worte , an early version of his Op. 30 No. 2. 32 Its agitated opening in B ♭ minor, reflecting his sister’s tribulations, gives way to a joyous conclusion in the major. The infant gained weight and thrived, and even became a symbol of political sensibilities. Euphoric with republican sympathies following the July Revolution in Paris, Fanny sewed the French tricolors into Sebastian’s swaddling clothes, much to the dismay of her husband.

During the last week of July, Marx joined Felix on an excursion to the Bavarian Alps. In Oberammergau they attended the Passion Play, performed every decade since the seventeenth century, and in Garmisch Felix sketched the Zugspitze. While Marx returned to Berlin, Felix proceeded to Austria and arrived on August 7 in Salzburg, where Metternich’s police seized a parcel of his music. In Linz four days later, Felix’s carriage passed one conveying Lea’s Viennese cousin, the Baroness Henriette von Pereira Arnstein; then, he changed mode of transportation. Forwarding his personal belongings to Vienna, he engaged a skiff with a gondolier’s deck, and “flew away … like an arrow at noon” down the Danube. 33 He detailed his impressions of the whirling eddies, the soft cacophony of church bells echoing from either bank, the nocturnal heavens illuminated by bursts of shooting stars, and the enveloping serenity, as if he “were eavesdropping on the music of the spheres.” 34 Near the middle of the month, he was in the Austrian capitol.

For some six weeks Felix resided in the Imperial City, unimpressed by its secret police and bureaucracy (most Viennese musicians, poets, and artists had government posts, confirming Metternich’s observation the city was administered, not ruled). In the few years since Beethoven’s death, Vienna had begun to stagnate in the arts; its chief musical products were light opera and uninspired piano music for middle-class households. At the court-controlled Kärtnerthortheater, where Beethoven’s Fidelio had been premiered, Felix found his friend Franz Hauser, the principal baritone, singing entrenched Italian opera (“until some fire falls from heaven, things will not mend,” Felix reported to Devrient 35 ). Matters did not improve when the theater’s director, Franz Lachner, asked Felix if the St. Matthew Passion was by Bach. Vestiges of Beethoven’s genius were difficult to discern (not a single pianist, Felix noted, played the master’s music), though Felix met several of the composer’s acquaintances who had served at his funeral: the poet Grillparzer, aging Bohemian composer Adalbert Gyrowetz, violinist Mayseder, piano manufacturer Streicher, music publishers Haslinger and Mechetti, Beethoven’s faithful acolyte Carl Czerny, and cellist Merk, with whom Felix played billiards. 36 Felix sent to Berlin distinctly uncomplimentary reports: Merk, smoking a cigar without exhaling, performed an Adagio, and the industrious Czerny was “like a tradesman on his day off,” churning out piano variations, arrangements, and salon pieces (among his hackwork was a revamping for sixteen pianos of the overture to Rossini’s Semiramide ). In short, the glories of Viennese classicism had passed: “Beethoven is no longer here, nor Mozart or Haydn either,” Felix wrote, and he took little solace when the octogenarian Abbé Stadler, musical confidante of Constanze Mozart, showed him the piano on which Haydn had composed The Seasons .

With Simon Sechter, who had instructed Schubert in fugue just weeks before the composer’s death in 1828, Felix exchanged “sweet canonical phrases.” And, he found stimulation in the company of the music historian R. G. Kiesewetter, who had assembled an imposing library of early choral music and regularly performed Palestrina, Victoria, Carissimi, and J. S. Bach. 37 An especially warm friendship developed between Felix and Aloys Fuchs (1799–1853), a passionate collector of musical autographs. 38 Felix later acquired for Fuchs manuscripts of composers ranging from Durante and Paisiello in the eighteenth century to Clementi, Attwood, and Moscheles in the nineteenth. On September 16 Fuchs offered his new friend a priceless gift, the “Wittgenstein” sketchbook of Beethoven, filled with hieroglyphic-like drafts for three major late works, the Piano Sonata Op. 109, Missa solemnis , and Diabelli Variations. 39

To promote his career, Felix sold Op. 11 and other works to Pietro Mechetti. Through Delphine, Felix met J. B. Streicher, who placed at the composer’s disposal a piano from his firm, with its characteristic light, bouncing action (Prellmechanik ). But apart from playing quartets with Mayseder, attending the Burgtheater, and conversing with musicians, Felix appears to have kept a low profile, by visiting his patrician relatives, the Eskeles in Hitzing, and the Arnsteins and Ephraims in Baden, where he performed on the parish church organ before a small circle of acquaintances. 40 Near the end of the Viennese sojourn, Felix traveled to Pressburg (Bratislava) to witness the coronation of the Crown Prince Ferdinand as king of Hungary, and was impressed by the colorful display of the Hungarian magnates, caparisoned horses of the nobility, and bands of gypsies and long-mustached commoners, all suggesting “oriental luxury, side by side with … barbarism.” 41

Felix intended to remain in Vienna for only a few weeks, but when news arrived in mid-September of instability in financial markets, he procrastinated and awaited his father’s advice. 42 Counteracting the “frivolous dissipation” of the Viennese, Felix immersed himself in sacred music and conceived for the Singakademie a setting of the Ave Maria . His principal creative effort was a “grave, little sacred piece,” a cantata on O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden , the Passion chorale treated prominently in the St. Matthew Passion. But the immediate stimulus for the work was visual: at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, Felix had viewed a painting attributed to the Spanish baroque artist Francisco de Zurbarán, showing John escorting Mary home from Calvary. 43

Felix now explored the tonal ambiguity of Paul Gerhardt’s seventeenth-century chorale (based on a secular melody of Hans Leo Hassler) and admitted no one would be able to discern whether the cantata was in C minor or E ♭ major. 44 Thus, in the first movement, with the chorale as a cantus firmus in the sopranos, the final choral strain reaches a cadence in E ♭ major, diverted by a few orchestral measures to an ambiguous half cadence in C minor. The lyrical middle movement, a freely composed aria in E ♭ major for Hauser, sets an unidentified text that elaborates Gerhardt’s poetry; glosslike, the music too occasionally alludes to the chorale ( ex. 8.6 ). The last movement, reviving the chorale to an accompaniment of pulsating string tremolos, adheres to C minor until the end, where the raised third (the tierce de Picardie of Baroque music) diverts the work to the major. By dividing the violas and cellos Felix gave the music an especially dark veneer, evidently to match the somber hues of the Munich painting. Musically the cantata is cut from a Bachian cloth; indeed, after examining the piece in 1841, the pedagogue Eduard Krüger assumed it was by Bach and caused a droll scene when Robert Schumann reported the misattribution to Felix. 45

Ex. 8.6 : Mendelssohn, O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden (1830), Second Movement

Shortly before Felix departed for Italy, Hauser gave him a volume of Lutheran hymns, a fresh incentive for ruminating about Bach. Felix promptly jotted down several melodies and set five during the next two years, Aus tiefer Noth , Vom Himmel hoch , Mitten wir im Leben sind , Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott , and Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh’ darein . From Graz he reported he was hard at work on his Hebrides Overture, now renamed Ouverture zur einsamen Insel (Overture to the Solitary Island ). 46 But a few days later, after reaching Mestre, his senses were challenged by another island, when, in the dead, nocturnal calm, he was rowed across the sea and entered the Grand Canal of Venice.

La serenissima was a republic no longer, having been vanquished by Napoleon in 1797 and ceded to the Austrians, who administered it as a police state. Like Byron, Felix stood on the Bridge of Sighs and contemplated the history-laden edifices hovering on the water, rising “as from the stroke of the enchanter’s wand” (Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage , iv, 1), the remembrance of former glory. Truly alone, without acquaintances in the city, 47 Felix played the tourist, strolling on the Piazza San Marco, experiencing the bustling dockyards of the Arsenale, and visiting the Dominican (S. Giovanni e Paolo), Franciscan (Frari), and Jesuit (Gesuiti) churches, and, of course, San Marco, symbol of Venetian opulence and the meeting of Byzantium and the West. Above all, the city’s art enticed the composer, who spent hours in the Accademia, the Scuole di S. Rocco, and other sites pondering the sixteenth-century masterpieces of Giorgione, Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese. While Turner in 1819 had preferred the energetic brushwork of Tintoretto’s Miracle of St. Mark , Felix was drawn to Titian’s Assumption in the Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari and marveled at its dynamic upward thrust, the figure of Mary floating on the cloud, her awe as she approaches God, the waving motion of the painting, and the angelic musicians greeting her ascent. 48

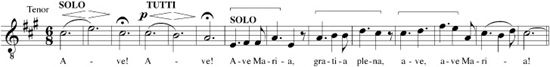

Felix may have had Titian’s altarpiece in mind on October 16 as he put final touches on the motet Ave Maria , Op. 23 No. 2, drafted in Vienna. For eight-part chorus and organ continuo, the graceful Marian setting employs responses between a solo tenor and the choir and, in the middle section (Sancta Maria, ora pro nobis ), a Baroque walking bass line. “I cling to the ancient masters, and study how they worked,” Felix wrote of his veneration of Titian to Zelter; 49 the same sentiment applied to his musical models. The principal subject rises from a compact, four-note motive presented in three sequential transpositions, the second of which, the “Jupiter” motive ( ex. 8.7 ), is familiar from the opening of the Reformation Symphony. Stylistically and spiritually the music harks back to seventeenth-century Catholic sacred music, although Abraham later found some passages too intricate to “accord with the simple piety, and certainly genuine Catholic spirit, which pervades the rest of the music.” 50 But on October 18, Felix reasserted his faith by finishing a somber setting of Aus tiefer Noth , Op. 23 No. 1, Luther’s paraphrase of Psalm 130. Cantata-like, the score has a symmetrical, five-movement plan, with two homophonic statements of the chorale forming the endpoints of the penitential psalm. In the center a tenor aria paraphrases the last two phrases of the chorale; and on either side are contrapuntal elaborations, a fugue built upon the first phrase, and a Bachian movement in imitative counterpoint with the chorale placed in the soprano.

Ex. 8.7 : Mendelssohn, Ave Maria , Op. 23 No. 2 (1830)

Memories of Delphine distracted Felix, and on October 16 he also composed two Lieder about their relationship. In the Reiselied

, published as Op. 19a No. 6, a traveler bids the rushing waves to greet his beloved and to relate how he has lost all happiness since their parting. Probably not coincidentally, the song is in E major, the key of the Rondo capriccioso

and Delphine’s Lied ohne Worte

. The second song is a Lied ohne Worte

for piano solo, textless though no less evocative. It is Felix’s first Venetian Gondellied

(Op. 19b No. 6), invoking the genre of the barcarolle with lilting rhythms in  for the lapping water, suffused in a muted G minor, with the melody doubled in thirds to suggest a love duet or, perhaps, a desired assignation among the canals. Felix dispatched the Lied to Munich, but Delphine never received it, for one night the police confiscated his manuscripts on suspicions they contained an encoded secret correspondence. Felix’s travel plans nearly went awry when his wealthy Viennese cousins failed to send an avviso

to Venetian bankers; Felix had to borrow 100 florins from a German acquaintance in order to continue the Grand Tour.

51

for the lapping water, suffused in a muted G minor, with the melody doubled in thirds to suggest a love duet or, perhaps, a desired assignation among the canals. Felix dispatched the Lied to Munich, but Delphine never received it, for one night the police confiscated his manuscripts on suspicions they contained an encoded secret correspondence. Felix’s travel plans nearly went awry when his wealthy Viennese cousins failed to send an avviso

to Venetian bankers; Felix had to borrow 100 florins from a German acquaintance in order to continue the Grand Tour.

51

From Bologna he crossed the Apennines in an open carriage and approached Florence on October 22, observing Brunelleschi’s dome looming out of a blue mist suspended between the girding hills. During the next week he devoted himself to the city’s art treasures in the Pitti and Uffizi, and compared the Medici Venus and Titian’s seductively recumbent Venus of Urbino (“divinely beautiful,” he wrote Paul, though “we can’t speak of it in front of the ladies” 52 ). Without succumbing to stendhalismo , the fainting spells that overwhelmed the French novelist when he visited the city, Felix explored the sixteenth-century Boboli Gardens and fled to the hills to take in the sweeping views from Bellosguardo and visit the Torre de Gallo, the Ghibelline tower from which Galileo reportedly made astronomical observations.

Felix arrived in Rome on November 1. Uncannily enough, his initial experiences paralleled those of Goethe, who had reached the Eternal City exactly forty-four years before. Felix first heard a requiem in the Quirinal and then experienced the “tranquil, … solid spirit” 53 in the Vatican described in Goethe’s Italienische Reise . Eagerly Felix sought out Raphael’s final masterpiece, the Transfiguration , meticulously copied by Hensel during his Roman sojourn, and assured his brother-in-law the original was no more powerful than the copy. But before Felix’s first reports could reach Berlin, Zelter was writing Goethe about his pupil, privately venting some anti-Semitic spleen: “Felix is probably now in Rome, which makes me quite happy, since his mother has always been against Italy, where she perhaps fears he will shed the last skin of his Jewishness.” 54

Avoiding the cold air of the Capitoline, Felix secured lodgings at Piazza di Spagna No. 5, flooded with morning sunlight and furnished with a Viennese grand and scores of Palestrina, Allegri, and other Italian composers. Nearby was that smoky haunt of artists, the Café Greco, and the pensione by the one-hundred-and-thirty rococo Spanish Steps, where Keats had succumbed to consumption in 1821. From the Piazza, Rome lay “in all her vast dimensions” before Felix “like an interesting problem to enjoy.” 55 He found several solutions: exploring the Colosseum and the ruins, losing all sense of proportion in St. Peter’s, and experiencing the incense and dim lighting of Santa Maria Maggiore, and the twelve oversized, baroque Apostles in the nave of San Giovanni in Laterano. There were relaxing walks in the Borghese Gardens and stunning views of the Campagna from the Aqua Paola, the early Baroque fountain on the Janiculum. And the chameleon hues of the Alban hills and fountains of Tivoli offered alluring respites.

If Felix had lived largely incognito in Florence and Venice, he now joined a circle of German and Italian officials, musicians, and artists. His cicerone was the Prussian minister, C. K. J. Bunsen, a friend of the Mendelssohns who had assisted Hensel in Rome. An avid musical amateur, Bunsen regularly performed Palestrina in his residence with members of the Papal Choir, led by their camerlegno , the priest Giuseppe Baini, who in 1828 had published the first substantial biography of the leading composer of the Counter-Reformation and “savior” of church polyphony. 56 Baini devoted himself to editing Palestrina’s music but was unequivocally opposed to modern instrumental music. Another priest, the bibliophile Fortunato Santini, struck up a warm friendship with Felix, whom Santini dubbed a faultless wonder (monstrum sine vitio ). 57 For some thirty years Santini had faithfully scored Renaissance and Baroque Italian polyphony from parts and amassed a library of over a thousand items, to which Felix had free access. To Felix’s amazement, the gregarious Abbate was interested in German music, translated into Italian the text of Der Tod Jesu , and arranged for the Passion cantata of the “infidel” Graun, as Felix called him, to be performed in Naples. Santini inquired too about the St. Matthew Passion, listened to Felix play Bach, and provided a copy of Handel’s Solomon for his young friend, who began an arrangement of the oratorio.

Felix found Roman musical life severely lacking. Supporting the concerts of the Accademia Filarmonica, which made Felix an honorary member, 58 was a piano, not an orchestra, and the thirty-two aging members of the Papal Choir were almost “completely unmusical.” With no prospect of a public Roman debut, Felix appeared in private gatherings. At Bunsen’s, after the papal singers had rendered a grave work of Palestrina, the brutissimo tedesco improvised, and there was an awkward moment when he searched for an apt subject, as “a brilliant piece would have been unsuitable, and there had been more than enough of serious music.” 59 But the musicians applauded and dubbed him l’insuperabile professorone . 60

Felix spent his free time in the company of German artists who had congregated in Rome, including the young Eduard Bendemann, Theodor Hildebrandt, and Carl Ferdinand Sohn from Düsseldorf, and Julius Hübner from Berlin. Understandably Felix was curious about the Nazarene brotherhood that in 1816 and 1817 had executed the frescos for the drawing room of his uncle Jacob Bartholdy. There was the familial bond with Philipp Veit, son of Dorothea Schlegel, and Felix found the aesthetic judgments of Wilhelm von Schadow sensible and to his liking. But a few meetings with J. F. Overbeck, a founding Nazarene member, instilled in Felix “a particular aversion to this brood.” 61 Seeking to revive medieval Christian art by uniting “Latin beauty and German inwardness,” 62 the majority of the society had embraced Catholicism and wore their hair and beards conspicuously long. They spoke condescendingly of Titian, and painted “sickly Madonnas, feeble saints, and milk-sop heroes.” 63 The last straw for Felix came in February and March 1831, when the Nazarenes abruptly altered their external appearance. Fearing political unrest in the Papal States and the ire of the Roman populace, they shaved their beards and mustaches but intended to readopt their Christlike trappings once the danger had passed. Felix found the tonsorial adjustments hypocritical. As for the frescos in the Casa Bartholdy, he was able to view them at the end of January 1831 but under less than ideal conditions. The drawing room was now the bedroom of English ladies, detracting considerably from the Old Testament scenes of Joseph and his brothers, the interpretation of the Pharaoh’s dreams, and the lunettes by Veit and Overbeck of the years of plenty and famine. In the middle of the room stood a four-post bed, which could do little more than allude to Veit’s panel depicting Joseph and Potiphar’s wife. Still, Felix found the frescos a “noble, regal idea.” 64

He was dutifully impressed with the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, celebrated for the Alexander frieze symbolizing Napoleon’s triumphant entry into Rome (1812). Felix went weekly to the Quirinal Palace to study the panels depicting the vanquished Babylonians bringing tribute to Alexander, the whole a glorification of classical antiquity. Felix visited the artist’s studio and offered piano improvisations while the leonine sculptor molded a figure in brown clay. It was a model of the Byron monument for Trinity College, Cambridge (1831), with the philhellene poet, “sufficiently gloomy and elegiac,” seeking inspiration amid classical ruins, his feet resting upon the capital of a broken column. 65

Another expatriate, Horace Vernet, enjoyed warm relations with Felix. The director of the French Academy in Rome since 1828, Vernet was known for rousing battle paintings glorifying the Revolution and Empire. But when Charles X forbade an official exhibition of Vernet’s work, the flamboyant artist converted his Parisian atelier into a museum, transformed a crepe-covered table into a Napoleonic tombeau , and admitted pilgrims from “the debris of the grande armée .” 66 In January 1831 Felix met Vernet at the French Academy, the Villa Medici on the Pincian Hill, and on learning of his admiration of Mozart’s Don Giovanni , contrived to work its themes into an improvisation, so delighting the Frenchman that he painted Felix’s portrait. It shows a young German gentleman wearing a black cravat and starched collar, with wavy dark locks and a somewhat bemused expression. Felix thought he appeared cross-eyed and that the portrait did not resemble him at all. 67 The same evening there was dancing, and Vernet’s daughter took up a tambourine in the middle of a saltarello. “I wished I had been a painter,” Felix reminisced, “for what a superb picture she would have made.” 68 Instead, he incorporated the whirling leaps of the dance into the finale of a new work forming in his head, the Italian Symphony.

Through Vernet, Felix met a no less colorful personality, Hector Berlioz, who, having finally won the coveted Prix de Rome, arrived at the Academy on March 11, 1831. Since Berlioz’s matriculation at the Paris Conservatoire in 1827, his unconventional scores had earned him the reputation of a hardened musical iconoclast. Three times he had competed for the prize and unsuccessfully submitted the required cantatas and stilted academic fugues. For the 1830 concours d’essai , the assigned text was La Mort de Sardanapale , treated by Byron and Delacroix, about the destruction of Nineveh and the debauched Assyrian king Sardanapalus. Here art approached life, for as Berlioz was finishing his score, the July Revolution erupted outside the Conservatoire and toppled the venal monarchy of Charles X. But by the time Berlioz found his hunting pistols, he was too late to join the uprising, which had transpired in three “glorious days.” On August 25, a few days after the jury awarded the Prix de Rome, Ferdinand Hiller introduced Berlioz to Felix’s father, who found the Frenchman “agreeable and interesting, and a great deal more sensible than his music.” Abraham reported Berlioz’s intention to seek permission to remain in Paris and forgo the five-year scholarship: “in all classes and trades here young people’s brains are in a state of fermentation: they smell regeneration, liberty, novelty, and want to have their share of it.” 69

For a few short weeks in Rome Felix and Berlioz enjoyed almost daily contacts, discussed art and music, and explored the city and its environs together. Berlioz recognized in Felix one of the most formidable musical talents of the period. They visited Tasso’s tomb at the convent of San’Onofrio, 70 and at the baths of Caracalla, the conversation turned to religion. According to Berlioz, Felix believed “firmly in his Lutheran faith.” 71 When Berlioz contradicted Felix’s piety with “outrageous” views, Felix slipped and fell on some ruins. “Look at that for an example of divine justice,” Berlioz exclaimed, “I blaspheme, you fall.” 72 While riding in the Campagna, they discussed the Queen Mab scene from Romeo and Juliet as a potential scherzo. Years later, Berlioz incorporated a “double attempt,” a vocal scherzetto and orchestral scherzo, into his dramatic symphony on Shakespeare’s play, but he dreaded that the composer of the Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture had already preempted the subject. 73

Felix’s opinion of Berlioz mirrored that of Abraham. Personally Felix found Berlioz likable, a skilled conversationalist with stimulating ideas. The two shared an enthusiasm for Gluck, and they escaped the oppressive sirocco by reading arias from Iphigénie en Tauride , with Felix accompanying Berlioz’s singing. Felix played Beethoven sonatas and shared a recently completed, “fine-spun yet richly colored work,” 74 the Hebrides Overture. But Felix could not abide the quirky, temperamental qualities of Berlioz’s musical style. At their first meeting, Felix had declared the opening of Sardanapalus “pretty awful.” He examined two Shakespearean works, the Overture to King Lear and the Fantasy on The Tempest , later redeployed as the finale of Lélio , sequel to the Symphonie fantastique . But Felix reserved his most acerbic comments for the finale of the symphony, the Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath (Ronde du sabbat ), with its extraordinary mixture of literary program, autobiography, and revolutionary orchestral devices. In a letter to Berlin he decried the “cold passion represented by all possible means: four timpani, two pianos for four hands, which are supposed to imitate bells, two harps, many large drums, violins divided into eight different parts, two different parts for the double basses which play solo passages, and all these means (which would be fine if they were properly used) express nothing but complete sterility and indifference, mere grunting, screaming, screeching here and there.” 75 Felix found the intrusion of autobiography—here Berlioz caricatures his idée fixe , the Shakespearean actress Harriet Smithson, as a harlot—unseemly and demeaning. Felix was quite aware of Berlioz’s emotional instability at this time in his life. When Lea hazarded the opinion that Berlioz’s hyperbolic musical effects must have some purpose, Felix answered, “I believe he wishes to be married…. I really cannot stand his obtrusive enthusiasm, and the gloomy despondency he assumes before ladies,—this stereotyped genius in black and white….” 76 In point of fact, Berlioz was desperate for news from his lover, the pianist Camille Moke. Upon learning of her infidelity, he left the Academy at the end of March and resolved to return to Paris to murder Camille, her new lover, and himself. By the time he abandoned the plot Felix had left for Naples. Upon his return in June, the two briefly renewed their friendship; not until 1843 did they cross paths again.

On November 30, 1830, Pope Pius VIII died after a brief reactionary reign. The day before Felix’s twenty-second birthday, the conclave of cardinals elected Gregory XVI. Because much of the winter was devoted to the funeral rites of Pius and the enthronement of the new pope, “all music … and large parties” came to an end, and Felix turned his critical gaze to the ceremonies of the Church. He described how the construction of the hundred-foot-high catafalque drowned out masses offered for Pius, and how the conclave inspired satires about the cardinals’ vices. From the farthest corner of St. Peter’s Felix viewed the bier in diminished perspective through the spiraling columns of St. Peter’s throne, as high as the palace in Berlin, and listened to the solemn chanting of the absolutions: “When the music commences, the sounds do not reach the other end for a long time, but echo and float in the vast space, so that the most singular and vague harmonies are borne towards you.” 77 The elevation of the new pope coincided with the arrival of the Roman Carnival, and Felix now indulged in the liberating frivolity and commingling of the classes—the motley masks, horse racing on the Corso, and throwing of confetti, a carefree explosion of humanity when Romans threw “dignity and prudence to the winds.” 78 The supplication of the Jews “to be suffered to remain in the Sacred City for another year” put Felix in a “bad humor,” for he could understand neither the Jewish oration nor the Christian response. A week later, on February 12, he joined a horseback excursion around the walls of Rome, but on his return he found soldiers with loaded arms occupying the piazzas and no signs of merriment. 79 The July Revolution had triggered revolts in Modena and Parma (Paris was then the locus of the carbonari , the Italian revolutionary society), and sympathetic disturbances in the Papal States had prompted the suspension of the carnival.

There ensued some uneasy weeks while Felix assured his family of his safety. In March the Austrians suppressed the uprisings, and Felix decided to remain in Rome to witness Holy Week. He described services in St. Peter’s and the Quirinal: the pope distributing twisted palms to the cardinals arrayed in a quadrangle on Palm Sunday; the psalmody alternating between two choirs during nocturns on Wednesday, culminating with the pope kneeling before the altar and the Miserere ; the washing of the pilgrims’ feet on Thursday; the adorning of the cross by the shoeless pontiff on Good Friday; the symbolic baptism of a child, representing Jews and Moslems, on Saturday at St. John Lateran; and the pope’s High Mass on Sunday. In addition to the constant chanting (Felix detected eight different formulae for the psalms but found the Gregorian monophony a “mechanical monotony” 80 ), there was sacred polyphony—Palestrina’s Improperia (Reproaches) for the Adoration of the Cross and Victoria’s St. John Passion (1585). Felix judged the latter, in which chant alternated with choruses for the turba scenes, abstract and unconvincing when compared to the dramatic cogency of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion; Victoria offered neither “a simple narrative, nor yet a grand, solemn, dramatic truth.” 81 Instead, the chorus (“very tame Jews indeed!” Felix observed) sang the same music for et in terra pax and Barabbas , and no musical distinction was drawn between Pilate and the Evangelist.

The legendary Miserere of Gregorio Allegri, a setting of Psalm 51 sung by the Papal Choir during Holy Week since the seventeenth century, especially piqued Felix’s interest. A papal ban on copying this work had magnified its allure over the decades; when the fourteen-year-old Mozart visited St. Peter’s in 1770, he summoned his prodigious memory to prepare his own copy. In 1831 Felix partially replicated this feat by recording some passages in letters to Berlin, including one striking refrain, in which the soprano part soared to an elevated C, transforming the male voices into “angels from on high.” Perceptively, Felix surmised that underlying this sublime effect were elementary harmonic sequences, to which various embellishments had accrued over time, so that the work’s beauty was fundamentally “earthly and comprehensible.” 82

During the Roman sojourn Felix composed a great deal of sacred music, alternating between Catholic and Lutheran texts that seemingly relived the narrative of the Reformation Symphony. He visited the Roman monastery where Luther had arrived a priest in 1511 and left a reformer. In the end, Felix remained a devout Protestant. Hauser’s gift of Lutheran hymns proved a wellspring of inspiration. Felix’s first setting, finished on November 20, was Mitten wir im Leben sind , based on the Reformer’s reworking of a ninth-century antiphon. This powerful, stark composition—Felix wrote that it growled angrily or whistled darkly 83 —unfolds in three strophes, each concluding with “Kyrie eleison.” Felix’s music employs only the first two phrases of the chorale. Several choral techniques capture the grim images of mankind, encircled by the fires of hell, appealing to the Lord for salvation: dividing the eight-part ensemble into its male and female parts, combining the two for expressive homophony, and injecting compact imitative motives into the texture. A gem among Felix’s sacred music (Johannes Brahms later prized the autograph), the motet is conspicuously un-Bachian, as if Felix temporarily ignored his penchant for complex linear counterpoint.

Far less imposing is Verleih’ uns Frieden , the Lutheran Da pacem Domine . Felix conceived this work as a canon (the duetlike cellos at the opening are a vestige of this plan) but again avoided a contrapuntal display in favor of three direct supplications for the basses, sopranos, and full choir. The orchestral accompaniment supports the gradual swelling of registers, with low strings for the first, and winds and violins for the second and third, as the gentle prayer for peace becomes more fervent. Robert Schumann treasured this expressive miniature; “Madonnas by Raphael and Murillo,” he mused, “cannot remain long from view.” 84

Two other Lutheran chorales, Vom Himmel hoch and Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott , inspired full-scale cantatas that anticipated the grandeur of Felix’s first oratorio, St. Paul. Vom Himmel hoch , dated January 28, 1831, falls into six movements, with the celebrated Christmas hymn featured in the first, third, and sixth; the intervening movements offer freely composed arias and an arioso. The brightly scored first movement—the music bursts forth with a descending violin figure from “on high”—suggests a fantasy on the first two phrases of the chorale (not unlike the finale of the Reformation Symphony), before the entire melody emerges at the end of the movement. Felix again eschews the Bachian prototype of weaving a web of imitative counterpoint around one voice that intones the chorale. In the finale, he accompanies the chorale with sweeping string arpeggiations and festive wind fanfares that take us farther from Bach; indeed, Felix dispenses with the final phrase of the melody, to bring the work to a radiant conclusion in a freely composed coda.

Similarly, much of Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott , finished in March 1831, employs only the first two phrases of the chorale, the Lutheran Credo. Respecting the tripartite division of the text, Felix apportioned his score into three movements, with successively faster rhythmic values: a walking bass line in quarter notes for the first, and eighth notes and triplets for the second and third. And, he coordinated the rhythmic crescendo with other means, bolstering the strings with winds and trombones for the last two movements, and setting off the imitative, fugal counterpoint of the first two with a forceful unison statement of the chorale in the last. Finally, in the closing pages he sprang one more surprise by supplementing the first two phrases of the chorale with his own, freely composed extension of the melody. 85

Among the Catholic texts set in Rome are Felix’s motets for female choir and organ, composed on the last two days of 1830 but not released until 1838, as the Drei Motetten , Op. 39. They were inspired by the fifteenth-century French church atop the Spanish Steps, the Trinità dei monti, where Felix enjoyed commanding views of the city at dusk, and studied the expressive singing of cloistered French nuns. He resolved to write sacred pieces they might perform for the “barbaro Tedesco , whom they also never beheld.” 86 The motets include Veni Domine (No. 1), for the third Sunday in Advent, with barcarolle-like rhythms and responsorial singing. In 1837, Felix replaced O beata et benedicta , a short homophonic setting for the Feast of the Trinity, 87 by Laudate pueri (No. 2), a setting of verses from Psalms 113 and 128. Its euphonious melodic lines appear to recall the Kyrie of Palestrina’s Missa Assumpta est Maria , which Baini may have introduced to Felix. Surrexit pastor (No. 3), for the second Sunday after Easter, treats Christ the Good Shepherd. Here Felix enlarges the chorus from three to four parts, not to accommodate imitative polyphony but to reinforce the largely consonant, diatonic harmonies that characterize these motets.

Arguably the most impressive of Felix’s Roman sacred works is Psalm 115, Non nobis Domine

(“Not unto us, O Lord”), finished on November 15, 1830, and scored for soloists, chorus, and orchestra. Felix had sketched the work in 1829 in England,

88

when he found inspiration examining the autograph of Handel’s Dixit Dominus

(composed during that composer’s Roman sojourn of 1707). Here Felix discovered another cantata-like setting in G minor of a Vulgate text, Psalm 110. The two internal movements of Felix’s composition, a duet with chorus and baritone arioso, give full expression to a warm, Italianate lyricism; embedded in the arioso (“The Lord shall increase you more and more”) is the four-note psalm intonation familiar from the opening of the Reformation

Symphony. The finale (“The dead praise not the Lord”) begins in the key of the arioso, E

♭

major, as an eight-part, a cappella chorus sings the last two psalm verses in stately block harmonies. Felix redirects the “final” cadence to G minor, and now, in a subdued postlude, the chorus revives the text of the first verse. A few measures later, the principal theme of the first movement reappears, metrically transformed from the original  to

to  time, an eerie reminiscence that unifies the whole (

ex. 8.8

). For five years, Felix set aside the composition; when the Bonn firm of Simrock published it as Op. 31 in 1835, the Latin text appeared alongside a new German translation (“Nicht unserm Namen, Herr”), prepared by Felix himself, in order to render the Latin psalm marketable to German taste.

time, an eerie reminiscence that unifies the whole (

ex. 8.8

). For five years, Felix set aside the composition; when the Bonn firm of Simrock published it as Op. 31 in 1835, the Latin text appeared alongside a new German translation (“Nicht unserm Namen, Herr”), prepared by Felix himself, in order to render the Latin psalm marketable to German taste.

Ex. 8.8 : Mendelssohn, Psalm 115 (Non nobis Domine ), Op. 31 (1830), Third Movement

Felix’s visit to the timeless city thus facilitated an immersion into sacred Catholic music, yet confirmed his identity as a Protestant German composer. But as he studied Gregorian chant in St. Peter’s and admired Palestrina’s mellifluous polyphony, Felix also took up several major works of a decidedly romantic and modern stance. He made progress on the Scottish Symphony, though the eruption of spring in March banished his “misty Scotch mood,” and instead he took up the brightly hued Italian Symphony, of which he evidently sketched three movements in Rome. And, he began to compose the cantata Die erste Walpurgisnacht and conjured up vivid musical imagery for the clashes in Goethe’s ballade between the early Christians and Druids on the Brocken. For Rebecka Felix drafted a wistful Lied ohne Worte in A minor, later subsumed into the first published set as Op. 19b No. 2. But the most significant accomplishment was the first draft of the Hebrides Overture, finished on Abraham’s birthday, December 11, 1830. For some time Felix had struggled with the title, which he renamed Ouverture zur einsamen Insel (Overture to the Solitary Island ). 89 He left no clues about the meaning of this revision: perhaps he was recollecting the bleak image of the tiny, windswept Staffa buffeted by the ocean; perhaps he was recalling the Ossianic poems, where Fingal’s fleet is labeled “the ships of the lonely isles”; or perhaps he was alluding to the second canto of Sir Walter Scott’s Lady of the Lake , which describes Ellen’s refuge as “the lonely isle.” 90 By December 16 Felix completed a second score of the overture that reverted to the original title, Die Hebriden . 91 Like Die einsame Insel , Die Hebriden was longer than the final, published version. 92 The hypercritical Felix was still not content and wrote Fanny that the noisy end of the exposition was lifted from the Reformation Symphony. 93 Temporarily banishing the seascapes of Die Hebriden from his mind, he instead prepared to visit the sun-drenched coast of Naples.

In the company of German painters, Felix departed Rome on April 10, 1831, and followed the Appian Way south. Rapidly crossing the malariainfested Pontine Marshes, they paused in Gaeta, where Grillparzer had written the poem that inspired Fanny’s Italien . Recalling his sister’s Lied, Felix now surrendered to sensual landscapes of fragrant lemon and orange groves, with Vesuvius and the Bay of Naples in the distance. On April 12 he stood on a balcony in Naples and could survey more clearly the dormant volcano, the islands of Ischia and Procida, and off the Sorrentine coast, the enchanting Capri. Though he renewed his friendship with Julius Benedict, conductor of Neapolitan opera, there were some disappointments. Felix regretted not finding smoke rising from Vesuvius and, at Abraham’s bidding, abandoned a plan to emulate Goethe’s itinerary by visiting Sicily. For nearly two months Felix indulged in a Neapolitan lassitude: he sketched the indescribable scenery, worked on his cantata, and read Sterne, Fielding, and his grandfather’s Phaedon . He was critical of the social polarization he found: a sprawling underclass of desperate beggars and thieves, and a dissolute upper class. Felix felt keenly the lack of a prosperous middle class. The balmy atmosphere was “suitable for grandees who rise late, … then eat ice, and drive to the theater at night, where again they do not find anything to think about”; but also suitable for “a fellow in a shirt, with naked legs and arms, who also has no occasion to move about—begging for a few grani when he has literally nothing left to live on.” 94

Nor did Neapolitan musical life satisfy Felix. He compared the orchestra and chorus to those of provincial German towns and was annoyed to observe the first violinist at the opera beating time on a tin candlestick, the metallic tapping sounding “somewhat like obbligati castanets, only louder.” 95 He deplored the quality of singing, for the best Italian soloists had left for London and Paris; only the fiorituri of the French soprano Joséphine Fodor, whom he heard in private, were taste ful. For several weeks the theaters were closed in honor of San Gennaro, patron saint of Naples, whose blood, preserved in a reliquary, was expected to liquefy in May. 96 Consequently, Felix left no description of the renowned Teatro San Carlo, although he did meet Donizetti, who had filled the vacuum caused by Rossini’s departure in 1822 and was busily churning out operas, sometimes, Felix reported, in the space of ten days. If Donizetti’s reputation fell into jeopardy, he might devote as much as three weeks to an opera, “bestowing considerable pains on a couple of arias in it, so that they may please the public, and then he can afford once more to … write trash.” 97 (A few years later Felix reassessed this opinion and committed to memory much of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor and La Favorite .) But Donizetti’s lack of industry seems to have infected the critic as well: Jules Cottrau, son of the leading Neapolitan music publisher, reported that Felix was now “seized by idleness and somewhat abandoned music.” 98

Indeed, he devoted much time to tourism and the “tragedy” of the Present and the Past, by contrasting the colorful if grim reality of Naples with the constant reminders of Roman and Greek antiquity—Virgil’s grave at Posillipo; the eerily preserved ruins of Pompeii (“as if the inhabitants had just gone out” 99 ); the terraced villas and thermal baths of Baia, where Odysseus moored; the Sibyl’s cave at Cumae and nearby Lake Avernus, entrance to the classical underworld; and, at the most southern point of Felix’s tour, the majestic temples of Paestum. There were limitless opportunities for drawing with his companions, Wilhelm von Schadow, Theodor Hildebrandt, Eduard Bendemann, and Carl Sohn. Along the Gulf of Salerno Felix recorded a breathtaking view of Amalfi, later worked up into a vibrant water color (see p. 329): in the foreground, a languid fountain reflecting ruined columns; beyond, a dramatic drop to the medieval maritime town, its bleached buildings perched on the jutting cliffs of the gulf (plate 11 ). The islands, fabled in antiquity and modernity as sybaritic resorts, did not fail to entice Felix and his companions, though on Procida they found women wearing Greek dress, who did “not look at all prettier for doing so.” 100 On Ischia, they ascended on mules the extinct volcano Monte Epomeo, and on the acacia-scented Capri they climbed in blistering heat five-hundred-and-thirty-seven steps to Anacapri, where Felix surveyed mosquelike churches with rounded domes. Above all, he yielded to the allure of the Blue Grotto, “rediscovered” only in 1826. Rather than a concert overture, the visit inspired a vivid description. The water resembled panes of opal glass; through the narrow aperture of the entrance the sun filled the cavern with refracting light, producing magical aquamarines on the dome of the cave. It was as if one “were actually living under the water for a time.” 101

On June 5 Felix began winding up his affairs in Rome. Writing to Thomas Attwood in polished English, Felix disclosed he had “finished” a new symphony, from which we might infer that his sketch of the Italian Symphony was completed during the Neapolitan sojourn. Still, he continued to lament the state of Italian music: “The fortunate circumstances which formerly made this country a country of arts seem to have ceased and arts with them.” 102 He discussed with Berlioz the musical scene in Paris 103 and in letters home broached the possibility of returning to London, “that smoky place” fated to be his “favorite residence,” 104 where he intended to meet Paul, about to leave the parental nest to join a London banking firm. To Felix’s concern, the family dynamic had been strained in February, when Rebecka revealed her desire to marry Dirichlet. Again Lea opposed the match, presumably because the young mathematician did not have sufficient means; not until November 5 was the engagement official. 105 Fanny endeavored to comfort her sister but also found joy in completing a cantata, Lobgesang , for Sebastian’s first birthday. Based largely on scriptural texts, the composition celebrates childbirth and reaffirms Fanny’s difficult pregnancy by drawing on John 16:21: “When a woman is in labor, she has pain, because her hour has come. But when her child is born, she no longer remembers the anguish because of the joy of having brought a human being into the world.” The work opens with a Handelian pastoral for orchestra and contains a graceful soprano aria; still, Felix detected several infelicities in the orchestration and was unconvinced by the selection of texts, for “not everything in the Bible” is “suggestive of music.” 106

Departing Rome on June 18, 1831, Felix traveled via Terni and Arezzo to Florence, and again imbibed freely of the surfeit of art in the Uffizi. The Tribune Room became his observation post; with a few glances he could survey the Venus de Medici and masterpieces by Raphael, Perugino, and his preferred Titian. Later, in the 1870s, Samuel Butler targeted Felix’s effusive description of these treasures. In Butler’s scathing indictment of Victorian society, The Way of All Flesh , the Englishman George Pontifex, in the midst of a grand tour, endured three hours in the Uffizi succumbing to “genteel paroxysms of admiration.” Felix claimed to have spent two hours in the Tribune Room and innocently provided grist for Butler’s mill: “I wonder how many chalks Mendelssohn gave himself for having sat two hours on that chair. I wonder how often he looked at his watch to see if his two hours were up…. But perhaps if the truth were known his two hours was [sic ] not quite two hours.” 107

Passing through Genoa, Felix reached Milan, capitol of Austrian Lombardy, in early July. At the Brera, he admired Raphael’s Marriage of the Virgin (Sposalizio ), later the inspiration for Franz Liszt’s impressionistic piano piece. Felix finished a draft of Die erste Walpurgisnacht and pondered whether to add a “symphonic” overture or short introduction “breathing of spring.” He met several foreign musicians, including the Russian composer M. I. Glinka, accompanied by the tenor Nicola Ivanov. 108 Then there was Carl Thomas Mozart (1784–1858), the elder surviving son of the composer, for whom Felix rendered the overtures to Don Giovanni and The Magic Flute . Mozart was among the very first to hear portions of Die erste Walpurgisnacht . And finally, Felix met the Baroness Dorothea Ertmann, an accomplished pianist to whom Beethoven had dedicated the Piano Sonata in A major, Op. 101. Felix and the Baroness played sonatas for each other, and she regaled him with anecdotes about Beethoven, how he used a candlesnuffer as a toothpick, and how, when she lost her last child, he comforted her by “speaking” in tones at the piano for over an hour. 109

In Milan Felix took stock of Italy. To Devrient’s insistence he write opera, Felix replied he would find a worthy libretto in Munich on his return journey, and that in Italy he had composed sacred music from inner necessity. He remained unrelenting in his criticism of Italian musical culture: a Bavarian barmaid, he opined, sang better than musicians trained in Italy, who “ape the little originalities, naughtinesses, and exaggeration of the great singers, and call that method.” Italy was a “land of art, because it is a chosen land of nature, where there is life and beauty everywhere.” 110 But the “land of the artist” remained Germany, and Felix now considered whether he should strengthen ties to London, Paris, and Munich, or return to the “stationary, unperturbed” life in Berlin. There, Felix acknowledged, after the revival of the St. Matthew Passion, he had been offered the directorship of the Singakademie. But after his return from England, there had been no further discussion; now, in order to accept it honorably, he felt compelled to stage another public event in Berlin, several concerts of his own music. 111

Meanwhile, the Alps loomed before him. In the waning days of July he reached the Borromean Islands, of which Fanny had dreamed in 1822. At the baroque palazzo on the Isola Bella, he found lush gardens with recurring hedges of lemons, oranges, and aloes, “as if, at the end of a piece, the beginning were to be repeated,” a technique of which Felix was fond. 112 He entered Switzerland via the Simplon Pass and, having made a diversion after Martigny to Chamonix to admire again Mont Blanc, reached Geneva on August 1. There he learned Abraham had sustained serious losses in a failed Hamburg bank. 113 But of immediate concern was the weather; as Felix began to retrace in reverse part of the 1822 Swiss holiday, from Vevay to Interlaken, the heavens opened up, flooding much of the countryside. Traveling became laborious or impossible; roads and bridges were washed out, and Felix often ventured forth on foot. Near Interlaken, on August 10, he worked on two Lieder, a setting of Goethe’s Die Liebende schreibt (The Lover Writes ), published posthumously as Op. 86 No. 3, and an unfinished Reiselied on verses of Uhland ( ex. 8.9 ). 114 The texts poeticize Felix’s separation from a beloved (Delphine?) and his identity as a romantic wanderer. Goethe’s poem inspired a gentle series of pedal points in the accompaniment and avoidance of a stable tonic sonority until the end, where the female persona asks for a sign from her lover. Uhland’s verses, about a traveler riding into a moonless, starless land beset by raging winds, prompted more insistent pedal points, as if Felix sought to recapture the mood of Schubert’s Erlkönig , with its celebrated nocturnal ride. The choice of key, A minor, seems calculated to underscore the distance from Munich and Delphine, whose lyrical voice in Die Liebende schreibt sings in E ♭ major.

Ex. 8.9a: Mendelssohn, Die Liebende schreibt , Op. 86 No. 3 (1831)

Ex. 8.9b: Mendelssohn, Reiselied (1831)

In Engelberg, Felix visited the twelfth-century Benedictine Abbey and, a “very Saul among the prophets,” 115 participated in a Mass at the organ. At the end of August he ascended the Rigi and again witnessed a sublime dawn on the summit, before persevering through the inundations to Appenzell and St. Gallen. He left Switzerland a practiced yodeler and on September 5 crossed the Rhine to Bavarian Lindau. Finding an organ, he played J. S. Bach’s hauntingly beautiful chorale setting of Schmücke dich, O liebe Seele to his heart’s content. The shabby, rainsoaked pedestrian now changed into a “town gentleman, with visiting-cards, fine linen, and a black coat.” 116

He completed that transformation in Munich, but not before reading newspaper accounts of the advancing Asiatic cholera and longing to see his family. But Abraham insisted Felix adhere to his plan, and so he gave a concert of his own music on October 17 at the Odeon Hall. Once again he raised his English baton to direct the Symphony in C minor and the Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream , premiered the Piano Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 25, and, at the king’s request, improvised on “Non più andrai” from Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro . A few days before there was a private performance for the queen, who commented that Felix’s extemporizing had transported the rapt royal audience, whereupon Felix “begged to apologize for carrying away Her Majesty, etc.” 117 He enjoyed casual music making with several Munich acquaintances—the gregarious clarinetist Baermann, the diffident virtuoso pianist Adolf Henselt, and, of course, Josephine Lang and Delphine von Schauroth. In the year before his return to Munich, Josephine had made great strides in composition—her newest Lieder contained “unalloyed musical delight”; Felix offered daily lessons in counterpoint and recommended she study with Zelter and Fanny in Berlin. 118

Delphine’s musicianship too had improved; her playing displayed ease of execution and “sparkled with fire”—and she had become “very pretty,” resembling a papoose (Steckkissen ). But when King Ludwig played matchmaker and urged Felix to marry her, the flustered composer chose to sustain their relationship through piano music. On September 18 he finished a virtuoso solo piece in two movements, a lyrical Andante in B major joined to an impetuous Allegro in B minor. 119 Reminiscent of the Rondo capriccioso , the composition later appeared with orchestral accompaniment as the Capriccio brillant , Op. 22. Felix also completed and dedicated to Delphine the Piano Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 25. Though Felix’s Italian letters refer to ideas for the new concerto, he drafted most of the work and scored it hastily in Munich. One clear sign is that the autograph full score 120 does not contain the piano part, which Felix presumably performed from memory. Another is that on October 6, less than two weeks before the premiere, Delphine herself contributed a “deafening” passage, 121 presumably one of the noisy octave or arpeggiation passages in the first movement.

In three connected movements, Op. 25 is Felix’s first concerto to observe the telescoped formal plan of Weber’s Konzertstück . Thus, in the first movement he truncates the traditional opening orchestral tutti and enables the soloist to appear dramatically after a terse, crescendo-like introduction. The piano entrance resembles more a cadenza than a thematic utterance, and elsewhere too the music expresses a certain thematic freedom and formal spontaneity. For example, the second theme swerves from the expected mediant key, B ♭ , to the remote key of D=. The luminous, nocturne-like Andante explores the sharp key of E, an unusual choice after G minor but not coincidentally the key of the Rondo capriccioso and Delphine’s Lied ohne Worte for Felix. The effervescent finale erupts in a bright G major and, like the finale of Weber’s Konzertstück , exploits two thematic ideas, the first doubled in octaves, the second a turning figure concealed in glittery virtuoso passagework. To tie the composition together, Felix recalls material from the first movement just before the jubilant coda. Popular through much of the nineteenth century, Op. 25 was gently caricatured in Berlioz’s Evenings with the Orchestra , where thirty-one competing pianists perform it on an Erard, causing the instrument to ignite in a spontaneous Da capo , “flinging out turns and trills like rockets.” 122

Apart from the public concert, Felix’s other goal was to secure a Munich opera commission. When it arrived at the end of October, he proudly sent a copy to Berlin, 123 as evidence of his new professional stature. Authorized to “negotiate with any German poet of renown,” Felix began to search for a libretto—like so many of his operatic aspirations, an unfulfilled quest. In Stuttgart, he endeavored to consult Ludwig Uhland but missed the poet and proceeded to Frankfurt. There he shared his recent sacred music with Schelble, who suggested Felix compose a new oratorio, and thereby planted the seed for St. Paul . Felix enjoyed artistic exchanges with his cousin, Philipp Veit, director of the Städelsche Art Institute, but tactfully avoided mentioning the painter’s mother, Dorothea Schlegel, in letters to Berlin. Declaring himself a German musician, Felix arranged to meet the dramatist/novelist K. L. Immermann (1796–1840) in Düsseldorf and arrived there late in November, having first visited the music publisher Simrock in Bonn to discuss the publication of Op. 23.

At the time of Felix’s encounter with Immermann (November 27–December 4), the writer had yet to produce his novels Die Epigonen (1836), treating the decline of the Westphalian aristocracy, and Münchhausen (1838), about the madcap adventures of a baron later linked to a mental illness. In 1832 Immermann would become the director of the theater in Düsseldorf; a few months before, Felix, thirteen years his junior, approached him for a libretto. The composer and dramatist left conflicting accounts of their meeting. Felix, who had heard Immermann could be prickly, reported the dramatist received him with the greatest friendship 124 (Abraham was unimpressed and recommended that Felix find a French libretto and translate it into German). Immermann admired Felix’s music, but detected in the unsolicited visit a “hook of egoism” and confided to his brother that the composer pursued him like a young maiden hanging onto her mother’s skirts. 125 The dramatist read portions of his new trilogy, Alexis , about Peter the Great’s son who was tortured to death in 1718, but the tragedy failed to inspire Felix’s operatic muse (in 1834, he did set the gloomy “Death Song of the Boyars,” from the first of the three plays, Die Bojaren ). Instead, the two took up Shakespeare’s comedy The Tempest . Felix then departed for Paris, confident he had secured a librettist.

On December 9, he found the metropolis seething politically, as Louis-Philippe consolidated his rule by aligning himself with the newly empowered middle class (juste milieu ). The failed Bourbon monarchy of legitimacy was exchanged for an experimental parliamentary monarchy, and the “citizen king,” donning galoshes and carrying an umbrella, mixed freely with his subjects. The relaxed restrictions on the press rendered him an easy target, and Honoré Daumier’s caricatures depicted Louis-Philippe as a corrupt, pear-shaped monarch.

In letters home Felix alluded to the baneful effect of the juste milieu on French culture. Politics and sensuality were the “two grand points of interest, round which everything circles.” 126 Felix attended sessions of the bicameral Chambers of Peers and Deputies. Euphoric from the revolution, citoyens were brandishing tricolored ribbons, and the parliament was reportedly preparing to debate whether all French males had the right from birth to wear the Order of the Legion of Honor. Egalitarianism swept over musical life as well. French pianos manufactured by Herz, Erard, and Pleyel all bore the inscription Médaille d’or: Exposition de 1827 , and Felix’s respect “seemed to diminish.” And when Kalkbrenner, who specialized in “purloining” themes, embraced romanticism in a piano fantasy titled Der Traum (The Dream ), Henri Herz followed suit with an equally vapid programmatic piece, so that “all Paris” dreamed. 127

Nowhere did Felix decry more harshly the philistinism of the bourgeoisie than in Robert le diable , which premiered in November 1831 and catapulted his countryman Giacomo Meyerbeer into the forefront of French grand opera. Felix was particularly offended by a cloister scene in which nuns, including one played by the ravishing Italian dancer Marie Taglioni, attempted to seduce the hero; “I consider it ignoble,” he wrote somewhat prudishly, “so if the present epoch exacts this style, … then I will write oratorios.” Robert’s father, the satanic Bertram, who attempted to lead his son astray, was a “poor devil.” In Felix’s view the work pandered to everyone, with ingratiating melodies for singers, harmony for the cultured, colorful orchestration for the Germans, and dancing for the French, but ultimately its plot, stretched thin over five acts, remained implausible. 128

According to Ferdinand Hiller, Felix cropped his hair to avoid being mistaken for Meyerbeer. 129 Nor did Felix find much companionship among other German emigrés in Paris, including adherents of the Young Germany movement, such as Ludwig Börne and Heinrich Heine, who, like Felix, had converted from Judaism to Protestantism but had embraced more liberal political ideologies. Börne had made a career of attacking Goethe for not turning his pen to promote just social causes; Börne’s unrelenting railing against Germany and his French “phrases of freedom” were repugnant to Felix, as was “Dr. Heine with everything ditto.” 130 Felix saw little of Heine, who was “entirely absorbed in liberal ideas and in politics,” and had infected Felix’s friend Hermann Franck, who like a magpie, now chattered “abuse against Germany.” 131 Matters were not helped when Felix learned of Goethe’s death on March 22; seerlike, Felix predicted that Zelter would soon follow the poet.