Directory

CONTENTS

ACCOMMODATION

BUSINESS HOURS

CHILDREN

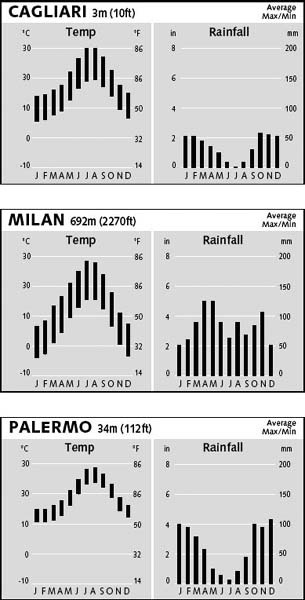

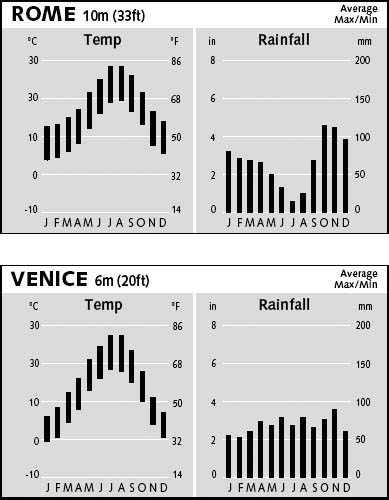

CLIMATE CHARTS

COURSES

CUSTOMS REGULATIONS

DANGERS & ANNOYANCES

DISCOUNT CARDS

EMBASSIES & CONSULATES

FOOD & DRINK

GAY & LESBIAN TRAVELLERS

HOLIDAYS

INSURANCE

INTERNET ACCESS

LEGAL MATTERS

MAPS

MONEY

POST

SHOPPING

SOLO TRAVELLERS

TELEPHONE

TIME

TOURIST INFORMATION

TRAVELLERS WITH DISABILITIES

VISAS

VOLUNTEERING

WOMEN TRAVELLERS

WORK

ACCOMMODATION

Accommodation in Italy can range from the sublime to the ridiculous with prices to match. Hotels and pensioni (guesthouses) make up the bulk of the offerings, covering a rainbow of options from cheap, nasty and ill-lit dosshouses near stations to luxury hotels considered among the best on the planet. Youth hostels and camping grounds are scattered across the country. Other options include charming B&B-style places that continue to proliferate, villa and apartment rentals, and agriturismi (farm stays). Some of the latter are working farms, others converted farmhouses (often with pool). Mountain walkers will find rifugi (alpine huts) handy. Capturing the imagination still more are the options to stay in anything from castles to convents and monasteries.

An original option born in the Friuli Venezia Giulia region is the albergo diffuso (www.albergodiffuso.com). In several villages, various apartments and houses are rented to guests through a centralised hotel-style reception in the village.

In this book a range of prices is quoted, from low to high season; these are intended as a guide only. Hotels are listed according to three categories (budget, midrange and top end). Half-board equals breakfast and either lunch or dinner; full board includes breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Prices can fluctuate enormously depending on the season, with Easter, summer and the Christmas—New Year period being the typical peak tourist times. There are many variables. Expect to pay top prices in the mountains during the ski season (December to March). Summer is high season on the coast, but in the parched cities can equal low season. In August especially, many city hotels charge as little as half price. It is always worth considering booking ahead in high season (although in the urban centres you can usually find something if you trust to luck).

As an average guide, a budget double room can cost up to €80, a midrange one from €80 to €200 and top-end anything from there to thousands of euros for a suite in one of the country’s premier establishments. Price depends greatly on where you’re looking. A bottom-end budget choice in Venice or Milan will set you back the price of a decent midrange option in, say, rural Campania. Where possible and appropriate, we have presented prices with the maximum low- and high-season rates thus: s €40–60, d €80–130, meaning that a single might cost €40 at most in low season and a double €130 at most in high season.

Some hotels barely alter their prices throughout the year. This is especially true of the lower-end places, although in low season there is no harm in trying to bargain for a discount. You may find hoteliers especially receptive if you intend to stay for several days.

For more on costs, Click here.

To make a reservation, hotels usually require confirmation by fax or, more commonly, a credit-card number. In the latter case, if you don’t show up you will be docked a night’s accommodation.

Agriturismo & B&Bs

Holidays on working farms, or agriturismi, are popular with travellers and property owners looking for extra revenue. Accommodation can range from simple, rustic affairs to luxury locations where little actual farming is done and the swimming pool sparkles. Agriturismo business has long boomed in Tuscany and Umbria, but is also steadily gaining ground in other regions.

Local tourist offices can usually supply lists of operators. For detailed information on agriturismo facilities throughout Italy check out Agriturist (www.agriturist.com) and Agriturismo.com (www.agriturismo.com). Other sites include Network Agriturismo Italia 2005 (www.agriturismo-italia2005.com), which in spite of its name is updated annually, Agriturismo-Italia.net (www.agriturismo-italia.net), Agriturismoitalia.com (www.agriturismoitalia.com) and Agriturismo Vero (www.agriturismovero.com).

B&B options include everything from restored farmhouses, city palazzi and seaside bungalows to rooms in family houses. Tariffs per person cover a wide range, from around €25 to €75. For more information, contact Bed & Breakfast Italia ( 06 687 86 18; www.bbitalia.it; Corso Vittorio Emanuele II 282, Rome, 00186).

06 687 86 18; www.bbitalia.it; Corso Vittorio Emanuele II 282, Rome, 00186).

Camping

Most camping grounds in Italy are major complexes with swimming pools, restaurants and supermarkets. They are graded according to a star system. Charges often vary according to the season, rising to a peak in July and August. Such high-season prices range from €6 to €20 per adult, free to €12 for children under 12, and from €5 to €25 for a site. In the major cities, grounds are often a long way from the historic centres. Many camping grounds offer the alternative of bungalows or even simple, self-contained flats. In high season, some only offer deals for a week at a time.

Independent camping is not permitted in protected areas but, out of the main tourist season, independent campers who choose spots that aren’t visible from the road and who don’t light fires shouldn’t have too much trouble. Get permission from the landowner if you want to camp on private property.

Lists of camping grounds are available from local tourist offices or can be looked up on various sites, including www.campeggi.com, www.camping.it and www.italcamping.it. The Touring Club Italiano (TCI) publishes the annual Campeggi in Italia (Camping in Italy), listing all camping grounds, and the Istituto Geografico de Agostini publishes Guida ai Campeggi in Europa (Guide to Camping in Europe), sold together with Guida ai Campeggi in Italia. Both are available in major bookshops.

Other sites worth looking up are www.canvasholidays.com, www.eurocamp.co.uk, www.keycamp.co.uk and www.select-site.com (on this site it’s possible to make individual site bookings).

Convents & Monasteries

What about a night or two in monastic peace? Some convents and monasteries let out cells or rooms as a modest revenue-making exercise and happily take in tourists, while others are single sex and only take in pilgrims or people who are on a spiritual retreat. Many do not take in guests at all. Convents and monasteries generally impose a fairly early curfew. Charges hover around €40/75/100 for a single/double/triple, although some charge more like €65/100 for singles/doubles.

As a starting point, take a look at the website of the Chiesa di Santa Susana (www.santasusanna.org/comingToRome/convents.html), an American Catholic church in Rome. On this site, it has searched out convent and monastery accommodation options around the country. Don’t ask the church to set things up for you – staff has simply put together the information. Getting a spot is generally up to you contacting the individual institution – however one central booking agency for convents and monasteries (see below) has popped up recently. Note that some places are just residential accommodation run by religious orders and not necessarily big on monastic atmosphere.

It was probably just a matter of time before someone set up a central booking centre for monasteries – check out www.monasterystays.com.

Another site worth a look is www.initaly.com/agri/convents.htm, for options in Abruzzo, Emilia-Romagna, Lazio, Liguria, Lombardy, Puglia, Sardinia, Sicily, Tuscany, Umbria and the Veneto. You pay US$6 to access the online newsletter with addresses. At www.realrome.com/accommconvents.html you will find a list of Roman convents that generally take in young single women. A useful if ageing publication is Eileen Barish’s The Guide to Lodging in Italy’s Monasteries. Another is Guida ai Monasteri d’Italia, by Gian Maria Grasselli and Pietro Tarallo. It details hundreds of monasteries, including many that provide lodging.

Hostels

Ostelli per la Gioventù (youth hostels) are run by the Associazione Italiana Alberghi per la Gioventù (AIG; Map;  06 487 11 52; www.ostellionline.org; Via Cavour 44, Rome), affiliated with Hostelling International (HI; www.hihostels.com). A valid HI card is required in all associated youth hostels in Italy. You can get this in your home country or direct at many hostels.

06 487 11 52; www.ostellionline.org; Via Cavour 44, Rome), affiliated with Hostelling International (HI; www.hihostels.com). A valid HI card is required in all associated youth hostels in Italy. You can get this in your home country or direct at many hostels.

Pick up a booklet on Italian hostels, with details of prices, locations and so on, from the national head office of AIG. Nightly rates vary from around €16 to €20, which usually includes a buffet breakfast. You can often get lunch or dinner for €10.

Accommodation is generally in segregated dormitories and it can be basic, although many hostels offer singles/doubles (for around €30/50) and family rooms.

Hostels will sometimes have a lock-out period between about 9am and 1.30pm. Check-in is usually not before 1pm and in many hostels there is a curfew from around 11pm. It is usually necessary to pay before 9am on the day of departure.

A growing contingent of independent hostels offers alternatives to HI hostels. Many are barely distinguishable from budget hotels. One of many hostel websites is www.hostelworld.com.

Hotels & Pensioni

There is often little difference between a pensione and an albergo (hotel). However, a pensione will generally be of one- to three-star quality and traditionally it has been a family-run operation, while an albergo can be awarded up to five stars. Locande (inns) long fell into much the same category as pensioni, but the term has become a trendy one in some parts and reveals little about the quality of a place. Affittacamere are rooms for rent in private houses. They are generally simple affairs.

Quality can vary enormously and the official star system gives only limited clues. One-star hotels/pensioni tend to be basic and usually do not offer private bathrooms. Two-star places are similar but rooms will generally have a private bathroom. At three-star joints you can usually assume reasonable standards. Four- and five-star hotels offer facilities such as room service, laundry and dry-cleaning.

Prices are highest in major tourist destinations. They also tend to be higher in northern Italy. A camera singola (single room) costs from €25. A camera doppia (twin beds) or camera matrimoniale (double room with a double bed) will cost from around €40.

Tourist offices usually have booklets with local accommodation listings. Many hotels are also signing up with (steadily proliferating) online accommodation-booking services. You could start your search here:

- Alberghi in Italia (www.alberghi-in-italia.it)

- All Hotels in Italy (www.hotelsitalyonline.com)

- Hotels web.it (www.hotelsweb.it)

- In Italia (www.initalia.it)

- Travel to Italy (www.travel-to-italy.com)

Mountain Huts

The network of rifugi in the Alps, Apennines and other mountains in Italy is usually only open from July to September. Accommodation is generally in dormitories but some of the larger refuges have doubles. The price per person (which usually includes breakfast) ranges from €17 to €26 depending on the quality of the refuge (it’s more for a double room). A hearty postwalk single-dish dinner will set you back another €11.50.

Rifugi are marked on good walking maps. Some are close to chair lifts and cable-car stations, which means they are usually expensive and crowded. Others are at high altitude and involve hours of hard walking. It is important to book in advance. Additional information can be obtained from the local tourist offices.

The Club Alpino Italiano (CAI; www.cai.it, in Italian) owns and runs many of the mountain huts. Members of organisations such as the Australian Alpine Club and British Mountaineering Council can enjoy discounted rates for accommodation and meals by obtaining a reciprocal rights card (for a fee).

Rental Accommodation

Finding rental accommodation in the major cities can be difficult and time-consuming – rental agencies (local and foreign) can assist, for a fee. Rental rates are higher for short-term leases. A small apartment or a studio anywhere near the centre of Rome will cost around €1000 per month and it is usually necessary to pay a deposit (generally one month in advance). Expect to spend similar amounts in cities such as Florence, Milan, Naples and Venice. Apartments and villas for rent are listed in local publications such as Rome’s weekly Porta Portese and the fortnightly Wanted in Rome. Another option is to answer an advertisement in a local publication to share an apartment. If you are staying for a few months and don’t mind sharing, check out university noticeboards for student flats with vacant rooms.

If you’re looking for an apartment or studio to rent for a short stay (such as a week or two) the easiest option is to check out the websites of agencies dealing in this kind of thing:

- Guest in Italy (www.guestinitaly.com) An online agency, with apartments (mostly for two to four people) ranging from about €120 to €450 a night.

- Holiday Lettings (www.holidaylettings.co.uk) Has hundreds of apartments all over the country.

- Homelidays (www.homelidays.com) Here you will find apartments for rent all over the country. Smallish flats in central Florence for two or three people can start at around €450 a week and rise to €700.

- Interhome (www.interhome.co.uk) Here you book apartments for blocks of a week, starting at around UK£500-600 for two or three people in central Rome.

In major resort areas, such as popular coastal areas in summer and the ski towns in winter, the tourist offices have lists of apartments and villas for rent.

Villa Rentals

Long the preserve of the Tuscan sun, the villa-rental scene in Italy has taken off in recent years, with agencies offering villa accommodation – often in splendid rural locations not far from enchanting medieval towns or Mediterranean beaches – up and down the country. More eccentric options include renting trulli, the conical traditional houses of southern Puglia, or dammusi (houses with thick, whitewashed walls and a shallow cupola) on the island of Pantelleria, south of Sicily. You can start your search with the following agencies but there are dozens of operators.

For villas in the time-honoured and most popular central regions, particularly Tuscany and Umbria, check out the following:

- Cuendet (www5.cuendet.com) One of the old hands in this business; operates from the heart of Siena province in Tuscany.

- Ilios Travel (www.iliostravel.com) UK-based company with villas, apartments and castles in Venice, Tuscany, Umbria, Lazio, Le Marche, Abruzzo and Sardinia.

- Invitation to Tuscany (www.invitationtotuscany.com) Wide range of properties across Tuscany, Umbria & Liguria.

- Simpson (www.simpson-travel.com) Concentrates on Tuscany, Umbria, the Amalfi Coast and Sicily. It also has properties in Rome, Florence and Venice.

- Summer’s Leases (www.summerleases.com) Properties in Tuscany and Umbria.

Some agencies concentrate their energies on the south (especially Campania and Puglia) and the islands of Sicily and Sardinia:

- Costa Smeralda Holidays (www.costasmeralda-holidays.com) Concentrates on Sardinia’s northeast.

- Long Travel (www.long-travel.co.uk) From Lazio and Abruzzo south, including Sardinia and Sicily.

- Think Sicily (www.thinksicily.com) Strictly Sicilian properties.

- Voyages Ilena (www.voyagesilena.co.uk) For Sardinia and Sicily.

Operators offering villas and other short-term let properties across the country:

- Carefree Italy (www.carefreeitaly.com) Apartments and villas.

- Cottages & Castles (www.cottagesandcastles.com.au) An Australian-based specialist in villa-style accommodation in Italy.

- Cottages to Castles (www.cottagestocastles.com) UK-based operator with properties across the country and agents worldwide.

- Parker Villas (www.parkervillas.co.uk) Has properties all over Italy.

- Veronica Tomasso Cotgrove (www.vtcitaly.com) This London-based company also acts in the sale of property in Tuscany and Umbria.

Return to beginning of chapter

BUSINESS HOURS

Generally shops open from 9am to 1pm and 3.30pm to 7.30pm (or 4pm to 8pm) Monday to Saturday. Many close on Saturday afternoon and some close on a Monday morning or afternoon, and sometimes again on a Wednesday or Thursday afternoon. In major towns, most department stores and supermarkets have continuous opening hours from 10am to 7.30pm Monday to Saturday. Some even open from 9am to 1pm on Sunday.

Banks tend to open from 8.30am to 1.30pm and 3.30pm to 4.30pm Monday to Friday. They close at weekends but exchange offices usually remain open in the larger cities and in main tourist areas.

Central post offices open from 8am to 7pm from Monday to Friday and 8.30am to 7pm (in some cases only until noon) on Saturday. Smaller branches tend to open from 8am to 2pm Monday to Friday and 8.30am to noon on Saturday.

Farmacie (pharmacies) are generally open 9am to 12.30pm and 3.30pm to 7.30pm. Most shut on Saturday afternoon, Sunday and holidays but a handful remain open on a rotation basis (farmacie di turno) for emergency purposes. Closed pharmacies display a list of the nearest ones open. They are usually listed in newspapers and you can also check out www.miniportale.it (click on Farmacie di Turno and then the region you want).

Many bars and cafes open from about 8am to 8pm. Others then go on into the night serving a nocturnal crowd while still others, dedicated more exclusively to nocturnal diversion, don’t get started until the early evening (even if they officially open in the morning). Few bars anywhere remain open beyond 1am or 2am. Clubs (discoteche) might open around 10pm (or earlier if they have eateries on the premises) but things don’t get seriously shaking until after midnight.

Restaurants open noon to 3pm and 7.30pm to around 11pm or midnight (sometimes even later in summer and in the south), although the kitchen often shuts an hour earlier than final closing time. Most restaurants and bars close at least one day a week.

The opening hours of museums, galleries and archaeological sites vary enormously, although at the more important sites there is a trend towards continuous opening from around 9.30am to 7pm. Many close on Monday. Some of the major national museums and galleries remain open until 10pm in summer. Click here for the opening hours of tourist offices.

Return to beginning of chapter

CHILDREN

Practicalities

Italians love children but there are few special amenities for them. Always make a point of asking staff members at tourist offices if they know of any special family activities or have suggestions on hotels that cater for kids. Discounts are available for children (usually aged under 12 but sometimes based on the child’s height) on public transport and for admission to sites.

If you have kids, book accommodation in advance to avoid any inconvenience and, when travelling by train, reserve seats where possible to avoid finding yourselves standing. You can hire car seats for infants and children from most car-rental firms, but you should always book them in advance.

You can buy baby formula in powder or liquid form, as well as sterilising solutions such as Milton, at pharmacies. Disposable nappies (diapers) are available at supermarkets and pharmacies. Fresh cow’s milk is sold in cartons in supermarkets and in bars with a ‘Latteria’ sign. UHT milk is popular and in many out-of-the-way areas the only kind available. For info on eating out with children, Click here.

Sights & Activities

Successful travel with children can require a special effort. Don’t try to overdo things and make sure activities include the kids – older children could help in the planning of these. Try to think of things that might capture their imagination, like the sites at Pompeii, the Colosseum and the Roman Forum in Rome, and Greek temples in the south and on Sicily. Another good bet is the volcanoes in the south.

Water activities, from lolling on a beach to snorkelling or sailing, are always winners.

When choosing museums, throw in the odd curio that may be more likely to stir a young child’s fascination than yet another worthy art gallery! Boys will probably like such things as Venice’s Museo Storico Navale, while girls might enjoy the idea of a little fashion shopping with mum in Milan’s Golden Quad district. And while you’re in northern Italy, make a stopover at Gardaland, the amusement park near Lago di Garda in Lombardy, or at Italia in Miniatura in Emilia-Romagna.

Always allow time for kids to play, and make sure treats such as a whopping gelato or slice of their favourite pizza are included in the bag of tricks.

See also Lonely Planet’s Travel with Children or the websites www.travelwithyourkids.com and www.familytravelnetwork.com.

Return to beginning of chapter

CLIMATE CHARTS

Situated in the temperate zone and jutting deep into the Mediterranean, Italy is regarded by many tourists as a land of sunny, mild weather. However, due to the north—south orientation of the peninsula and the fact that it is largely mountainous, the country’s climate is variable. Click here for more information on when to go.

In the Alps, temperatures are lower and winters can be long and severe. Generally the weather is warm from July to September, although rainfall can be high in September. While the first snowfall is usually in November, light snow sometimes falls in mid-September and heavy falls can occur in early October. Freak snowfalls in June are not unknown at high altitudes. Mind you, with climate change, many ski resorts can remain distressingly snow-free until early January (the exceptionally snowy winter of 2008–09 notwithstanding!).

The Alps shield northern Lombardy and the Lakes area, including Milan, from the extremes of the northern European winter, and Liguria enjoys a mild, Mediterranean climate similar to that in southern Italy because it is protected by the Alps and Apennine range.

Winters are severe and summers torrid in the Po valley. Venice can be hot and humid in summer and, although not too cold in winter, it can be unpleasant if wet or when the sea level rises and acque alte (literally ‘high waters’) inundate the city. This is most likely in November and December. Along the Po valley, and in Venice especially, January and February can be surprisingly crisp and stunning.

In Florence, encircled by hills, the weather can be quite extreme but, as you travel towards the tip of the boot, temperatures and weather conditions become milder. Rome, for instance, has an average July and August temperature in the mid-20s (Celsius), although the impact of the sirocco (a hot, humid wind blowing from Africa) can produce stiflingly hot weather in August, with temperatures in the high 30s for days on end. Winters are moderate and snow is rare in Rome, although winter clothing (or at least a heavy overcoat) is still a requirement.

The south of Italy and the islands of Sicily and Sardinia have a Mediterranean climate. Summers are long, hot and dry, and winter temperatures tend to be relatively moderate, with daytime averages not too far below 10°C. These regions are also affected by the humid sirocco in summer.

Return to beginning of chapter

COURSES

Holiday courses are a booming section of the Italian tourist industry and they cover everything – from painting, art, sculpture, wine, food, photography and scuba diving to even hang-gliding. You will find details on various local courses throughout this book. US students looking to sign up for courses in Italy might want to check out the offerings at Study Abroad Italy (www.studyabroaditaly.com).

Apart from the following categories, possibilities range from history courses in Venice to fashion courses in Milan. Learn4good (www.learn4good.com) is a good place to start your search.

Cooking

Many people come to Italy just for the food so it is hardly surprising that cookery courses are among the most popular. Check out Mama Margaret (www.italycookingschools.com) for ideas on courses throughout the country;Click here for details on specific courses.

Language

Courses are run by private schools and universities throughout the country and are a great way to learn Italian while enjoying the opportunity to live in an Italian city or town. Among the more popular and reasonably priced options, the Università per Stranieri di Perugia (www.unistrapg.it) and the Università per Stranieri di Siena (www.unistrasi.it) are both set in beautiful medieval cities. Frequently these schools offer extracurricular or full-time courses in painting, art history, sculpture and architecture, too. One school in Siena, Saenaiulia ( 0577 441 55; www.saenaiulia.it), has a web link listing language schools around the country.

0577 441 55; www.saenaiulia.it), has a web link listing language schools around the country.

Florence and are teeming with Italian-language schools, while most cities and major towns have at least one.

The Istituto Italiano di Cultura (IIC), which has branches all over the world, is a government-sponsored organisation aimed at promoting Italian culture and language. This is a good place to start your search for places to study in Italy. The institute’s numerous branches worldwide include Australia (Sydney), Canada (Montreal), the UK (London) and the USA (Los Angeles, New York and Washington). The website of the Italian foreign ministry (www.esteri.it) has a full list of institutions; click on Diplomatic Network and then on Italian Cultural Institutes.

Painting

Art and painting courses abound, especially in Florence. One place to start looking is at Learn4good (www.learn4good.com), which has information on several art schools in Italy. It-Schools.com (www.it-schools.com) is also worth checking out.

Yoga

It will always be hard to close your senses to the food and drink of Italy, but another way to enjoy the country is with a little gentle bodywork. Yoga in Italy ( 0445 48 02 98; www.yogainitaly.it) offers a variety of week-long holidays combining yoga with anything from walks in the Chianti countryside to white-water rafting.

0445 48 02 98; www.yogainitaly.it) offers a variety of week-long holidays combining yoga with anything from walks in the Chianti countryside to white-water rafting.

Return to beginning of chapter

CUSTOMS REGULATIONS

Duty-free sales within the EU no longer exist (but goods are sold tax-free in European airports). Visitors coming into Italy from non-EU countries can import, duty free: 1L of spirits (or 2L wine), 50g perfume, 250mL eau de toilette, 200 cigarettes and other goods up to a total of €175; anything over this limit must be declared on arrival and the appropriate duty paid. On leaving the EU, non-EU citizens can reclaim any Value Added Tax (VAT) on expensive purchases (Click here).

Return to beginning of chapter

DANGERS & ANNOYANCES

It sometimes requires patience to deal with the Italian concept of service, which does not always seem to follow the maxim that the customer is always right. While often courteous and friendly, some people in uniform or behind a counter (including police officers, waiters and shop assistants) may regard you with supreme indifference.

Long queues are the norm in banks, post offices and government offices.

Pollution

Problems in the major cities are noise and air pollution, caused mainly by heavy traffic. A headache after a day of sightseeing in Rome or Milan is likely to be caused by breathing in carbon monoxide and lead, rather than simple tiredness.

In summer (and occasionally other seasons) pollution alerts come as a wake-up call in cities like Rome, Milan, Naples and Florence. The elderly, children and people with respiratory problems are warned to stay indoors. If you fit into one of these categories, keep yourself informed through the tourist office or your hotel. Often traffic is cut by half during these alerts by obliging drivers with odd and even number plates to drive on alternate days.

Watch where you step as dog poop on the pavements is a big-city irritation. Italian dog-owners are catching onto the idea of cleaning up their best friend’s daily doings, but this is by no means a universal courtesy.

Italy’s beaches can be polluted by industrial waste, sewage and oil spills from the Mediterranean’s considerable sea traffic. The best and cleanest beaches are on Sardinia, Sicily, less-populated southern areas of the mainland and Elba.

Smoking

Since early 2005, smoking in all closed public spaces (from bars to elevators, offices to trains) has been banned.

Theft

Pickpockets and bag-snatchers operate in most cities, especially Naples and Rome. Reduce the chances of such petty theft by wearing a money belt (with money, passport, credit cards and important documents) under your clothing. Wear bags or cameras slung across the body to make it harder to snatch them. If your hotel has a safe, use it.

Watch for groups of dishevelled-looking women and children asking you for money. Their favourite haunts are train stations, tourist sights and shopping areas. If you’ve been targeted by a group, take evasive action (such as crossing the street) or shout ‘Va via!’ (Go away!). Again, this is an issue mainly in Rome and Naples.

Parked cars, particularly those with foreign number plates or rental-company stickers, are prime targets. Try not to leave anything in the car and certainly not overnight. Car theft is a problem in Rome, Campania and Puglia.

In case of theft or loss, always report the incident to police within 24 hours and ask for a statement, otherwise your travel-insurance company won’t pay out.

Traffic

Italian traffic can seem chaotic, although it has improved a trifle now that Italian drivers have point-system licences. Drivers are not keen to stop for pedestrians, even at pedestrian crossings, and are more likely to swerve. Where this is the case, follow the locals (even if they seem bent on suicide) by marching out into the (swerving) traffic.

Confusingly, in some cities, roads that appear to be only for one-way traffic have lanes for buses travelling in the opposite direction – always look both ways before stepping onto the road.

Signposting is often confusing. It is not uncommon to see signs to the same place pointing in two opposing directions at once. This can be especially unnerving for drivers navigating their way out of a city for the first time (although one becomes accustomed to these ‘options’ after a while).

City driving can be nerve-wracking at first, with what seems a cavalier dodgem-cars element to it. Motorcyclists should be prepared for anything in the cities. Once you get the hang of Italian-style urban driving, though, you might come to like it!

Return to beginning of chapter

DISCOUNT CARDS

At museums and galleries, never hesitate to enquire after discounts for students, young people, children, families or the elderly. When sightseeing and wherever possible buy a biglietto cumulativo, a ticket that allows admission to a number of associated sights for less than the combined cost of separate admission fees.

Senior Cards

Senior citizens are often entitled to public-transport discounts but usually only for monthly passes (not daily or weekly tickets); the minimum qualifying age is 65 years.

Seniors (over 60) travelling extensively by rail should consider the one-year Carta d’Argento (Click here).

Admission to most museums in Rome is free for over-60s but in other cities (such as Florence) often no concessions are made for nonresidents. In numerous places, EU seniors have free entry to sights, sometimes only on certain days. Always ask.

Student & Youth Cards

Free admission to some galleries and sites is available to under-18s. Discounts (usually half the normal fee) are available for some sights to EU citizens aged between 18 and 25. An International Student Identity Card (ISIC; www.isic.org) is no longer sufficient at many tourist sites as prices are usually based on age, so a passport, driver’s licence or Euro<26 (www.euro26.org) card is preferable.

An ISIC card may still, however, prove useful for cheap transport, theatre and cinema discounts, as well as occasional discounts in some hotels and restaurants (check the lists on the ISIC website); similar cards are available to teachers (International Teacher Identity Card, or ITIC). For nonstudent travellers under 25, the International Youth Travel Card (IYTC) offers the same benefits.

Student cards are issued by student unionsand hostelling organisations as well as some youth travel agencies. In Italy, the Centro Turistico Studentesco e Giovanile (CTS; www.cts.it) youth travel agency can issue ISIC, ITIC and Euro<26 cards.

Return to beginning of chapter

EMBASSIES & CONSULATES

For foreign embassies and consulates in Italy not listed here, look under ‘Ambasciate’ or ‘Consolati’ in the telephone directory. In addition to the following, some countries run honorary consulates in other cities.

- Australia Rome (Map;

06 85 27 21, emergencies 800 877790; www.italy.embassy.gov.au; Via Antonio Bosio 5, 00161); Milan (Map;

06 85 27 21, emergencies 800 877790; www.italy.embassy.gov.au; Via Antonio Bosio 5, 00161); Milan (Map;  02 7770 4217; www.austrade.it; Via Borgogna 2, 20122)

02 7770 4217; www.austrade.it; Via Borgogna 2, 20122) - Austria (Map;

06 844 01 41; www.bmaa.gv.at; Via Pergolesi 3, Rome, 00198)

06 844 01 41; www.bmaa.gv.at; Via Pergolesi 3, Rome, 00198) - Canada (Map;

06 85 44 41; www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/canadaeuropa/italy; Via Zara 30, Rome, 00198)

06 85 44 41; www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/canadaeuropa/italy; Via Zara 30, Rome, 00198) - France Rome (Map;

06 68 60 11; www.france-italia.it; Piazza Farnese 67, 00186); Milan (Map;

06 68 60 11; www.france-italia.it; Piazza Farnese 67, 00186); Milan (Map;  02 655 91 41; Via della Moscova 12, 20121); Naples (Map;

02 655 91 41; Via della Moscova 12, 20121); Naples (Map;  081 598 07 11; Via Francesco Crispi 86, 80121); Turin (

081 598 07 11; Via Francesco Crispi 86, 80121); Turin ( 011 573 23 11; Via Roma 366, 10121); Venice (Map;

011 573 23 11; Via Roma 366, 10121); Venice (Map;  041 522 43 19; Palazzo Morosini, Castello 6140, 30123)

041 522 43 19; Palazzo Morosini, Castello 6140, 30123) - Germany Rome (Map;

06 49 21 31; www.rom.diplo.de; Via San Martino della Battaglia 4, 00185); Milan (Map;

06 49 21 31; www.rom.diplo.de; Via San Martino della Battaglia 4, 00185); Milan (Map;  02 623 11 01; www.mailand.diplo.de; Via Solferino 40, 20121); Naples (Map;

02 623 11 01; www.mailand.diplo.de; Via Solferino 40, 20121); Naples (Map;  081 248 85 11; www.neapel.diplo.de; Via Francesco Crispi 69, 80121)

081 248 85 11; www.neapel.diplo.de; Via Francesco Crispi 69, 80121) - Ireland (Map;

06 697 91 21; www.ambasciata-irlanda.it; Piazza Campitelli 3, Rome, 00186)

06 697 91 21; www.ambasciata-irlanda.it; Piazza Campitelli 3, Rome, 00186) - Japan Rome (Map;

06 48 79 91; www.it.emb-japan.go.jp; Via Quintino Sella 60, 00187); Milan (Map;

06 48 79 91; www.it.emb-japan.go.jp; Via Quintino Sella 60, 00187); Milan (Map;  02 624 11 41; Via Cesare Mangili 2/4, 20121)

02 624 11 41; Via Cesare Mangili 2/4, 20121) - Netherlands Rome (Map;

06 3228 6001; www.olanda.it; Via Michele Mercati 8, 00197); Milan (Map;

06 3228 6001; www.olanda.it; Via Michele Mercati 8, 00197); Milan (Map;  02 485 58 41; Via San Vittore 45, 20123); Naples (Map;

02 485 58 41; Via San Vittore 45, 20123); Naples (Map;  081 551 30 03; Via Agostino Depretis 114, 80133); Palermo (Map;

081 551 30 03; Via Agostino Depretis 114, 80133); Palermo (Map;  091 58 15 21; Via Enrico Amari 8, 90139)

091 58 15 21; Via Enrico Amari 8, 90139) - New Zealand Rome (Map;

06 853 75 01; www.nzembassy.com; Via Clitunno 44, 00198); Milan (Map;

06 853 75 01; www.nzembassy.com; Via Clitunno 44, 00198); Milan (Map;  02 7217 0001; Via Terraggio 17, 20123)

02 7217 0001; Via Terraggio 17, 20123) - Switzerland Rome (Map;

06 80 95 71; www.eda.admin.ch/roma; Via Barnarba Oriani 61, 00197); Milan (Map;

06 80 95 71; www.eda.admin.ch/roma; Via Barnarba Oriani 61, 00197); Milan (Map;  02 777 91 61; www.eda.admin.ch/milano; Via Palestro 2, 20121); Naples (Map;

02 777 91 61; www.eda.admin.ch/milano; Via Palestro 2, 20121); Naples (Map;  081 734 11 32; www.eda.admin.ch/napoli; Centro Direzionale, Isola B3, 80143)

081 734 11 32; www.eda.admin.ch/napoli; Centro Direzionale, Isola B3, 80143) - UK Rome (Map;

06 4220 0001; www.britishembassy.gov.uk; Via XX Settembre 80a, 00187); Florence (Map;

06 4220 0001; www.britishembassy.gov.uk; Via XX Settembre 80a, 00187); Florence (Map;  055 28 41 33; Lungarno Corsini 2, 50123); Milan (Map;

055 28 41 33; Lungarno Corsini 2, 50123); Milan (Map;  02 72 30 01; Via San Paolo 7, 20121); Naples (Map;

02 72 30 01; Via San Paolo 7, 20121); Naples (Map;  081 423 89 11; Via dei Mille 40, 80121)

081 423 89 11; Via dei Mille 40, 80121) - USA Rome (Map;

06 4 67 41; www.usis.it; Via Vittorio Veneto 119a, 00187); Florence (Map;

06 4 67 41; www.usis.it; Via Vittorio Veneto 119a, 00187); Florence (Map;  055 26 69 51; Lungarno Amerigo Vespucci 38, 50123); Milan (Map;

055 26 69 51; Lungarno Amerigo Vespucci 38, 50123); Milan (Map;  02 29 03 51; Via Principe Amedeo 2/10, 20121); Naples (Map;

02 29 03 51; Via Principe Amedeo 2/10, 20121); Naples (Map;  081 583 81 11; Piazza della Repubblica, 80122)

081 583 81 11; Piazza della Repubblica, 80122)

Return to beginning of chapter

FOOD & DRINK

Restaurant listings in this book are given in order of cheapest to most expensive, going by the price of a meal, unless otherwise stated. A meal in this guide consists of a primo (first course), a secondo (second course) and a dessert. Drinks are not included. The budget category is for meals costing up to €20, midrange is €20 to €45 and top end is anything over €45. These figures represent a halfway point between the expensive cities such as Milan and Venice and the considerably cheaper towns across the south. Indeed, a restaurant rated as midrange in one place might be considered cheap as chips in Milan. It is best to check the menu, usually posted by the entrance, for prices. Most eating establishments have a cover charge (called coperto; usually around €1 to €2) and servizio (service charge) of 10% to 15%.

A tavola calda (literally ‘hot table’) normally offers cheap, pre-prepared food and can include self-service pasta, roast meats and pizza al taglio (pizza by the slice).

A trattoria is traditionally a cheaper, often family-run version of a ristorante (restaurant) with less-aloof service and simpler dishes. An osteria is likely to be either a wine bar offering a small selection of dishes with a verbal menu, or a small trattoria. You can sometimes get food to accompany your tipples in an enoteca (wine bar).

Bars are popular hang-outs, serving mostly coffee, soft drinks and alcohol. They often sell brioche (breakfast pastry), cornetti (croissants), panini (bread rolls with simple fillings) and spuntini (snacks) to have with your drink.

You’ll find vegetarian and vegan restaurants in larger cities, such as Rome and Milan. Otherwise vegans can have a tough time. Many Italians seem to think cheese is vegetarian, so make sure your dish is ‘senza formaggio’ (without cheese). The good news is that most places usually do some good vegetable starters and side dishes.

Children’s menus are uncommon but you can generally ask for a mezzo piatto (half plate) off the menu. Kids are generally welcome in most restaurants but do not count on the availability of high chairs.

For an introduction to the famous Italian cuisine and wines, Click here. For information on the opening hours of restaurants, Click here.

Return to beginning of chapter

GAY & LESBIAN TRAVELLERS

Homosexuality is legal in Italy and well tolerated in the major cities. However, overt displays of affection by homosexual couples could attract a negative response in the more conservative south, and smaller towns. The legal age of consent is generally 16 (there are some exceptions where people below that age are concerned, in which case it can drop to as low as 13).

There are gay clubs in Rome, Milan and Bologna, and a handful in places such as Florence. Some coastal towns and resorts (such as the Tuscan town of Viareggio or Taormina in Sicily) have much more action in summer. For clues, track down local gay organisations or publications such as Pride, a national monthly magazine, and AUT published by Circolo Mario Mieli (www.mariomieli.org) in Rome. The useful website Gay.it (www.gay.it, in Italian) lists gay bars and hotels across the country. Arcigay & Arcilesbica ( 051 649 30 55; www.arcigay.it; Via Don Minzoni 18, Bologna), is a worthy national organisation for gays and lesbians.

051 649 30 55; www.arcigay.it; Via Don Minzoni 18, Bologna), is a worthy national organisation for gays and lesbians.

Check out the English-language GayFriendlyItalia.com (www.gayfriendlyitaly.com), which is produced by Gay.it. It has information on everything from hotels to homophobia issues and the law.

Return to beginning of chapter

HOLIDAYS

Most Italians take their annual holiday in August. This means that many businesses and shops close for at least a part of that month. The Settimana Santa (Easter week) is another busy holiday period for Italians.

Individual towns have public holidays to celebrate the feasts of their patron saints (Click here). National public holidays include the following:

- New Year’s Day (Capodanno or Anno Nuovo) 1 January

- Epiphany (Epifania or Befana) 6 January

- Easter Monday (Pasquetta or Lunedì dell’Angelo) March/April

- Liberation Day (Giorno della Liberazione) On 25 April – marks the Allied Victory in Italy, and the end of the German presence and Mussolini, in 1945.

- Labour Day (Festa del Lavoro) 1 May

- Republic Day (Festa della Repubblica) 2 June

- Feast of the Assumption (Assunzione or Ferragosto) 15 August

- All Saints’ Day (Ognissanti) 1 November

- Feast of the Immaculate Conception (Immaculata Concezione) 8 December

- Christmas Day (Natale) 25 December

- Boxing Day (Festa di Santo Stefano) 26 December

Return to beginning of chapter

INSURANCE

A travel-insurance policy to cover theft, loss and medical problems is a good idea. It may also cover you for cancellation or delays to your travel arrangements. Paying for your ticket with a credit card can often provide limited travel accident insurance and you may be able to reclaim the payment if the operator doesn’t deliver. Ask your credit-card company what it will cover.

For information on health insurance, check out Click here.

Return to beginning of chapter

INTERNET ACCESS

If you plan to carry your notebook or palmtop computer with you, carry a universal AC adaptor for your appliance (most are sold with these). Do not rely on finding wi-fi whenever you want it, as hot spots remain few and far between and often require payment. Another option is to buy a card pack with one of the Italian mobile-phone operators, which gives wireless access through the mobile telephone network. These are usually prepay services that you can top up as you go.

Most travellers make constant use of internet cafes and free web-based email such as Yahoo, Hotmail or Gmail. Internet cafes and centres are present, if not always abundant, in all cities and most main towns (don’t forget your incoming mail server name, account name and password). Prices hover at around the €5 to €8 mark per hour. For some useful internet addresses, Click here. By law, you must present photo ID (such as passport or drivers licence) to use internet points in Italy.

Return to beginning of chapter

LEGAL MATTERS

For many Italians, finding ways to get around the law is a way of life. This is partly because bureaucracy has long been seen by most (with some justification) as a suffocating clamp on just about all areas of human activity.

The average tourist will only have a brush with the law if robbed by a bag-snatcher or pickpocket.

Alcohol & Drugs

Italy’s drug laws were toughened in 2006 and possession of any controlled substances, including cannabis or marijuana, can get you into hot water. Those caught in possession of 5g of cannabis can be considered traffickers and prosecuted as such. The same applies to tiny amounts of other drugs. Those caught with amounts below this threshold can be subject to minor penalties.

The legal limit for blood-alcohol level is 0.05% and random breath tests do occur.

Police

If you run into trouble in Italy, you are likely to end up dealing with the polizia statale (state police) or the carabinieri (military police).

The polizia deal with thefts, visa extensions and permits (among other things). They wear powder blue trousers with a fuchsia stripe and a navy blue jacket. Details of police stations, or questure, are given throughout this book.

The carabinieri deal with general crime, public order and drug enforcement (often overlapping with the polizia). They wear a black uniform with a red stripe and drive night blue cars with a red stripe. They are based in a caserma (barracks), a reflection of their past military status (they came under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Defence).

One of the big differences between the police and carabinieri is the latter’s reach – even many villages have a carabinieri post.

Other police include the vigili urbani, basically local traffic police. You will have to deal with them if you get a parking ticket or your car is towed away. The guardia di finanza are responsible for fighting tax evasion and drug smuggling. The guardia forestale, aka corpo forestale, are responsible for enforcing laws concerning forests and the environment in general.

For national emergency numbers, see the inside front cover.

Your Rights

Italy still has antiterrorism laws on its books that could make life difficult if you are detained. You should be given verbal and written notice of the charges laid against you within 24 hours by arresting officers. You have no right to a phone call upon arrest. The prosecutor must apply to a magistrate for you to be held in preventive custody awaiting trial (depending on the seriousness of the offence) within 48 hours of arrest. You have the right not to respond to questions without the presence of a lawyer. If the magistrate orders preventive custody, you have the right to then contest this within the following 10 days.

Return to beginning of chapter

MAPS

City Maps

The city maps in this book, combined with tourist office maps, are generally adequate. More detailed maps are available in Italy at good bookshops, such as Feltrinelli. De Agostini, Touring Club Italiano (TCI) and Michelin all publish detailed city maps.

Road Atlases

If you are driving around Italy, the Automobile Association’s (AA) Road Atlas Italy, available in the UK, is scaled at 1:250,000 and includes 31 town maps. Just as good is Michelin’s Tourist and Motoring Atlas Italy, scaled at 1:300,000, with 74 town maps.

In Italy, De Agostini publishes a comprehensive Atlante Turistico Stradale d’Italia (1:250,000), which includes 140 city maps (the AA Road Atlas is based on this). TCI publishes an Atlante Stradale d’Italia (1:200,000) divided into three parts – Nord, Centro and Sud (€45 for the lot at www.touringclub.com). They contain a total of 147 city maps.

Many of these are available online. Check out TrekTools.com (www.trektools.com).

Small-Scale Maps

Michelin has a series of good foldout country maps. No 735 covers the whole country on a scale of 1:1,000,000. You could also consider the series of six area maps at 1:400,000. TCI publishes a decent map of Italy at 1:800,000, as well as a series of 15 regional maps at 1:200,000 (costing €7 each).

Walking Maps

Maps of walking trails in the Alps and Apennines are available at all major bookshops in Italy, but the best are the TCI bookshops.

The best walking maps are the 1:25,000 scale series published by Tabacco (www.tabaccoeditrice.com), covering an area from Bormio in the west to the Slovene border in the east. It also does maps on a grander scale. Kompass (www.kompass-italia.it) also publishes 1:25,000 scale maps of various parts of Italy, as well as a 1:50,000 series and several in other scales (including one at 1:7500 of Capri). The Club Alpino Italiano (CAI) produces many hiking maps too, and Edizioni Multigraphic Florence produces a series of walking maps concentrating mainly on the Apennines.

The series Guide dei Monti d’Italia, 22 grey hardbacks published by the TCI and CAI, consists of exhaustive walking guides with maps.

Return to beginning of chapter

MONEY

The euro is Italy’s currency. The seven euro notes come in denominations of €500, €200, €100, €50, €20, €10 and €5. The eight euro coins are in denominations of €2 and €1, and 50, 20, 10, five, two and one cents.

Exchange rates are given on the inside front cover of this book. For the latest rates, check out www.xe.com. For some hints on costs in Italy, turn to Click here.

Cash

There is little advantage in bringing foreign cash into Italy. True, exchange commissions are often lower than for travellers cheques, but the danger of losing the lot far outweighs such gains.

Credit & Debit Cards

Credit and debit cards can be used in a bancomat (ATM) displaying the appropriate sign. Visa and MasterCard are among the most widely recognised, but others like Cirrus and Maestro are also well covered. Only some banks give cash advances over the counter, so you’re better off using ATMs. Cards are also good for payment in most hotels, restaurants, shops, supermarkets and tollbooths.

Check any charges with your bank. Most banks now build a fee of around 2.75% into every foreign transaction. In addition, ATM withdrawals can attract a further fee, usually around 1.5%.

It is not uncommon for ATMs in Italy to reject foreign cards. Try a few more ATMs displaying your card’s logo before assuming the problem lies with your card (although, unfortunately, this may trigger alarms with your bank and lead it to block your card – make sure you always have some cash for calls home to your bank to explain what happened!).

If your card is lost, stolen or swallowed by an ATM, you can telephone toll free to have an immediate stop put on its use:

- Amex (

06 7290 0347 or your national call number)

06 7290 0347 or your national call number) - Diners Club (

800 864064)

800 864064) - MasterCard (

800 870866)

800 870866) - Visa (

800 819014)

800 819014)

Moneychangers

You can change money in banks, at the post office or in a cambio (exchange office). Post offices and most banks are reliable and tend to offer the best rates. Commission fluctuates and depends on whether you are changing cash or cheques. Generally, post-office commissions are lowest and the exchange rate reasonable. The main advantage of exchange offices is the longer hours they keep, but watch for high commissions and inferior rates.

Taxes & Refunds

A value-added tax of around 20%, known as IVA (Imposta di Valore Aggiunto), is slapped onto just about everything in Italy. If you are a non-EU resident and spend more than €155 (€154.94 to be more precise!) on a purchase, you can claim a refund when you leave. The refund only applies to purchases from affiliated retail outlets that display a ‘tax free for tourists’ (or similar) sign. You have to complete a form at the point of sale, then have it stamped by Italian customs as you leave. At major airports you can then get an immediate cash refund; otherwise it will be refunded to your credit card. For information, pick up a pamphlet on the scheme from participating stores.

Tipping

You are not expected to tip on top of restaurant service charges but you can leave a little extra if you feel service warrants it. If there is no service charge, the customer should consider leaving a 10% tip, but this is not obligatory. In bars, Italians often leave small change as a tip, maybe only €0.10. Tipping taxi drivers is not common practice, but you are expected to tip the porter at top-end hotels.

Travellers Cheques

Traditionally a safe way to carry money and possibly not a bad idea as a backup, travellers cheques have been outmoded by plastic. Various readers have reported having trouble changing travellers cheques in Italy and it seems most banks apply hefty commissions, even on cheques denominated in euros.

Visa, Travelex and Amex are widely accepted brands. Get most of your cheques in fairly large denominations to save on per-cheque commission charges. Amex exchange offices do not charge commission to exchange travellers cheques.

It’s vital to keep your initial receipt, along with a record of your cheque numbers and the ones you have used, separate from the cheques. Take along your passport as identification when you go to cash travellers cheques.

Phone numbers to report lost or stolen cheques:

- Amex (

800 914912)

800 914912) - MasterCard (

800 872050)

800 872050) - Visa (

800 874155)

800 874155)

Return to beginning of chapter

POST

Le Poste ( 803160; www.poste.it), Italy’s postal system, is reasonably reliable. The most efficient mail service is posta prioritaria (priority mail). For post office opening hours, Click here.

803160; www.poste.it), Italy’s postal system, is reasonably reliable. The most efficient mail service is posta prioritaria (priority mail). For post office opening hours, Click here.

Francobolli (stamps) are available at post offices and authorised tobacconists (look for the official tabacchi sign: a big ‘T’, usually white on black). Since letters often need to be weighed, what you get at the tobacconist for international airmail will occasionally be an approximation of the proper rate. Tobacconists keep regular shop hours Click here.

Postal Rates & Services

The cost of sending a letter by via aerea (airmail) depends on its weight, size and where it is being sent. Most people use posta prioritaria, guaranteed to deliver letters sent to Europe within three days and to the rest of the world within four to eight days. Letters up to 20g cost €0.65 within Europe, €0.85 to Africa, Asia and North and South America and €1 to Australia and New Zealand. Letters weighing 21g to 50g cost €1.45 within Europe, €1.50 to Africa, Asia and the Americas, and €1.80 to Australia and New Zealand.

Receiving Mail

Poste restante (general delivery) is known as fermo posta in Italy. Letters marked thus will be held at the counter of the same name in the main post office in the relevant town. Poste restante mail to Verona, for example, should be addressed as follows:

John SMITH,

Fermo Posta,

37100 Verona,

Italy

You will need to pick up your letters in person and you must present your passport or national ID.

Return to beginning of chapter

SHOPPING

Italy is a shopper’s paradise, so bring your plastic well charged up and even an empty bag for your purchases (or buy a new one while in Italy).

Fashion is probably one of the first things that springs to the mind of the serious shopper. The big cities and tourist centres, especially Milan, Rome and Florence, are home to countless designer boutiques spilling over with clothes, shoes and accessories by all the great Italian names, and many equally enticing unknowns.

Foodies and wine lovers will want to bring home some souvenirs for the kitchen, ranging from fine Parma ham to aromatic cheeses, from class wines (especially from Tuscany, Piedmont and the Veneto) to local tipples (such as Benevento’s La Strega, grappa from Bassano del Grappa, the almond-based Amaretto, and limoncello, the lemon-based liqueur common in Naples and Sicily as well as other parts of the south).

Many cities and provinces offer specialised products. Sicily is known for its ceramics, as is the town of Gubbia in Umbria. Shoes and leathergoods are one of Florence’s big calling cards. In Venice, seek out beautifully handmade Carnevale masks, along with Murano glassware and Burano lace.

Return to beginning of chapter

SOLO TRAVELLERS

The main disadvantage for solo travellers in Italy is the higher price they generally pay for accommodation. A single room in a hotel or pensione usually costs around two-thirds of the price of a double.

Return to beginning of chapter

TELEPHONE

Domestic Calls

As elsewhere in Europe, Italians choose from a host of providers of phone plans and rates, making it difficult to make generalisations about costs. A local call from a public phone costs €0.10 every minute and 10 seconds. For a long-distance call within Italy you pay €0.10 when the call is answered and then €0.10 every 57 seconds. Calling from a private phone is cheaper.

Telephone area codes all begin with 0 and consist of up to four digits. The area code is followed by a number of anything from four to eight digits. The area code is an integral part of the telephone number and must always be dialled, even when calling from next door. Mobile-phone numbers begin with a three-digit prefix such as 330. Toll-free (free-phone) numbers are known as numeri verdi and usually start with 800. Nongeographical numbers start with 840, 841, 848, 892, 899, 163, 166 or 199. The range of rates for these makes a rainbow look boring – beware that some can be costly. Some six-digit national rate numbers are also in use (such as those for Alitalia, rail and postal information).

International Calls

Direct international calls can easily be made from public telephones by using a phonecard. Dial  00 to get out of Italy, then the relevant country and area codes, followed by the telephone number.

00 to get out of Italy, then the relevant country and area codes, followed by the telephone number.

To call home, use your country’s direct-dialling services paid for at home-country rates (such as AT&T in the USA and Telstra in Australia). Get their access numbers before you leave home. Alternatively, try making calls from cheap-rate call centres or using international call cards, which are often on sale at newspaper stands.

To call Italy from abroad, call the international access number (usually 00), Italy’s country code ( 39) and then the area code of the location you want, including the leading 0.

39) and then the area code of the location you want, including the leading 0.

Directory Enquiries

National and international phone numbers can be requested at  1254 (or online at http://1254.alice.it). Another handy number, where operators will respond in several languages, is

1254 (or online at http://1254.alice.it). Another handy number, where operators will respond in several languages, is  89 24 12. These services have varying costs and can be dear.

89 24 12. These services have varying costs and can be dear.

Mobile Phones

Italy uses GSM 900/1800, which is compatible with the rest of Europe and Australia but not with North American GSM 1900 or the totally different Japanese system (though some GSM 1900/900 phones do work here). If you have a GSM phone, check with your service provider about using it in Italy and beware of calls being routed internationally (very expensive for a ‘local’ call).

Italy has one of the highest levels of mobile-phone penetration in Europe, and you can get a temporary or prepaid account from several companies if you already own a GSM, dual- or tri-band cellular phone. You will usually need your passport to open an account. Always check with your mobile-service provider in your home country to ascertain whether your handset allows use of another SIM card. If yours does, it can cost as little as €10 to activate a local prepaid SIM card (sometimes with €10 worth of calls on the card).

Of the four main mobile phone companies, TIM (Telecom Italia Mobile) and Vodafone have the densest networks of outlets across the country.

Payphones & Phonecards

Partly privatised Telecom Italia is the largest telecommunications organisation in Italy and its orange public payphones are liberally scattered about the country. The most common accept only carte/schede telefoniche (phonecards), although you’ll still find some that take cards and coins. Some card phones accept credit cards.

Telecom payphones can be found in the streets, train stations and some stores as well as in Telecom offices. Where these offices are staffed, it is possible to make international calls and pay at the desk afterwards. You can buy phonecards (most commonly €2.50 or €5) at post offices, tobacconists and newsstands. You must break off the top left-hand corner of the card before you can use it. Phonecards have an expiry date. This is usually 31 December or 30 June, depending on when you purchase the card.

Other companies, such as Infostrada and BT Italia, also operate a handful of public payphones, for which cards are usually available at newsstands.

You will find cut-price call centres in all of the main cities. Rates can be considerably lower than from Telecom payphones for international calls. You simply place your call from a private booth inside the centre and pay for it when you’ve finished. Alternatively, ask about international calling cards at newsstands and tobacconists. They can be hit-and-miss but are sometimes good value.

Return to beginning of chapter

TIME

Italy is one hour ahead of GMT. Daylight-saving time, when clocks are moved forward one hour, starts on the last Sunday in March. Clocks are put back an hour on the last Sunday in October. Italy operates on a 24-hour clock.

Return to beginning of chapter

TOURIST INFORMATION

The quality of tourist offices in Italy varies dramatically. Three tiers of tourist office exist: regional, provincial and local. They have different names, but roughly offer the same services, with the exception of regional offices, which are generally concerned with promotion, planning and budgeting.

Local & Provincial Tourist Offices

Throughout this book, offices are referred to as tourist offices rather than by their more elaborate titles. The Azienda Autonoma di Soggiorno e Turismo (AAST) is the local tourist office in many towns and cities of the south. AASTs have town-specific information and should also know about bus routes and museum opening times. The Azienda di Promozione Turistica (APT) is the provincial (ie main) tourist office, which should have information on the town you are in and the surrounding province. Informazione e Assistenza ai Turisti (IAT) has local tourist office branches in towns and cities, mostly in the northern half of Italy. Pro Loco is the local office in small towns and villages and is similar to the AAST office. Most tourist offices will respond to written and telephone requests for information.

Tourist offices are generally open from 8.30am to 12.30pm or 1pm and 3pm to 7pm Monday to Friday. Hours are usually extended in summer, when some offices also open on Saturday or Sunday.

Information booths at most major train stations tend to keep similar hours but in some cases operate only in summer. Staff can usually provide a city map, list of hotels and information on the major sights.

English, and sometimes French or German, is spoken at tourist offices in larger towns and major tourist areas. German is spoken in Alto Adige and French in much of the Valle d’Aosta.

Regional Tourist Authorities

As a rule, the regional tourist authorities are more concerned with planning and marketing than offering a public information service, with work done at a provincial and local level. Addresses of local tourist offices appear throughout the guide. Following are some useful regional websites. In some cases you need to look for the Tourism or Turismo link within the regional site. At the website of the Italian National Tourist Office (www.enit.it) you can find details of all provincial and local tourist offices across the country.

- Abruzzo (www.abruzzoturismo.it)

- Basilicata (www.aptbasilicata.it)

- Calabria (www.turiscalabria.it)

- Campania (www.in-campania.com)

- Emilia-Romagna (www.emiliaromagnaturismo.it)

- Friuli Venezia Giulia (www.turismo.fvg.it)

- Lazio (www.turislazio.it)

- Le Marche (www.le-marche.com)

- Liguria (www.turismoinliguria.it)

- Lombardy (www.turismo.regione.lombardia.it)

- Molise (www.regione.molise.it/turismo, in Italian)

- Piedmont (www.regione.piemonte.it/turismo, in Italian)

- Puglia (www.pugliaturismo.com)

- Sardinia (www.sardegnaturismo.it)

- Sicily (www.regione.sicilia.it/turismo)

- Trentino-Alto Adige (www.trentino.to, www.provincia.bz.it)

- Tuscany (www.turismo.toscana.it)

- Umbria (www.umbria.org)

- Valle d’Aosta (www.regione.vda.it/turismo)

- Veneto (www.veneto.to)

Tourist Offices Abroad

Information on Italy is available from the Italian National Tourist Office (ENIT;  06 4 97 11; www.enit.it; Via Marghera 2, Rome, 00185) in the following countries:

06 4 97 11; www.enit.it; Via Marghera 2, Rome, 00185) in the following countries:

- Australia (

02 9262 1666; italia@italiantourism.com.au; Level 4, 46 Market St, Sydney, NSW 2000)

02 9262 1666; italia@italiantourism.com.au; Level 4, 46 Market St, Sydney, NSW 2000) - Austria (

01 505 16 39; delegation.wien@enit.at; Kärntnerring 4, Vienna, A-1010)

01 505 16 39; delegation.wien@enit.at; Kärntnerring 4, Vienna, A-1010) - Canada (

416 925 4882; www.italiantourism.com; Suite 907, South Tower, 175 Bloor St East, Toronto, M4W 3R8)

416 925 4882; www.italiantourism.com; Suite 907, South Tower, 175 Bloor St East, Toronto, M4W 3R8) - France (

01 42 66 03 96; enit.direction@wanadoo.fr; 23 rue de la Paix, Paris, 75002)

01 42 66 03 96; enit.direction@wanadoo.fr; 23 rue de la Paix, Paris, 75002) - Germany Berlin (

030 247 8398; enit.berlin@t-online.de; Kontorhaus Mitte, Friedrichstrasse 187, 10117); Frankfurt (

030 247 8398; enit.berlin@t-online.de; Kontorhaus Mitte, Friedrichstrasse 187, 10117); Frankfurt ( 069 237 069; enit.ffm@t-online.de; Neue Mainzerstrasse 26, 60311); Munich (

069 237 069; enit.ffm@t-online.de; Neue Mainzerstrasse 26, 60311); Munich ( 089 531 317; enit.muenchen@t-online.de; Prinzregentenstrasse 22, 80333)

089 531 317; enit.muenchen@t-online.de; Prinzregentenstrasse 22, 80333) - Japan (

03 3478 2051; enittky@dream.com; 2-7-14 Minami Aoyama, Minato-ku, Tokyo, 107-0062)

03 3478 2051; enittky@dream.com; 2-7-14 Minami Aoyama, Minato-ku, Tokyo, 107-0062) - Netherlands (

020 616 82 46; amsterdam@enit.it; Stadhouderskade 2, 1054 ES Amsterdam)

020 616 82 46; amsterdam@enit.it; Stadhouderskade 2, 1054 ES Amsterdam) - Switzerland (

043 466 40 40; info@enit.ch; Uraniastrasse 32, Zurich, 8001)

043 466 40 40; info@enit.ch; Uraniastrasse 32, Zurich, 8001) - UK (

020 7399 3562; italy@italiantouristboard.co.uk; 1 Princes St, London W1B 2AY)

020 7399 3562; italy@italiantouristboard.co.uk; 1 Princes St, London W1B 2AY) - USA Chicago (

312 644 09 96; enitch@italiantourism.com; www.italiantourism.com; 500 North Michigan Ave, Suite 2240, IL 60611); Los Angeles (

312 644 09 96; enitch@italiantourism.com; www.italiantourism.com; 500 North Michigan Ave, Suite 2240, IL 60611); Los Angeles ( 310 820 1898; enitla@italiantourism.com; 12400 Wilshire Blvd, Suite 550, CA 90025); New York (

310 820 1898; enitla@italiantourism.com; 12400 Wilshire Blvd, Suite 550, CA 90025); New York ( 212 245 5618; enitny@italiantourism.com; 630 Fifth Ave, Suite 1565, NY 10111)

212 245 5618; enitny@italiantourism.com; 630 Fifth Ave, Suite 1565, NY 10111)

Return to beginning of chapter

TRAVELLERS WITH DISABILITIES

Italy is not an easy country for disabled travellers and getting around can be a problem for wheelchair users. Even a short journey in a city or town can become a major expedition if cobblestone streets have to be negotiated. Although many buildings have lifts, they are not always wide enough for wheelchairs. Not an awful lot has been done to make life for the deaf and/or blind any easier either.

The Italian National Tourist Office (above) in your country may be able to provide advice on Italian associations for the disabled and information on what help is available. It may also carry a small brochure, Services for Disabled Passengers, published by Italian railways, which details facilities at stations and on trains. It also has a national helpline at  199 303060.

199 303060.

A handful of cities also publish general guides on accessibility, among them Bologna, Milan, Padua, Reggio Emilia, Turin, Venice and Verona.

Some organisations that may help:

- Accessible Italy (

+378 94 11 11; www.accessibleitaly.com) A San Marino—based company that specialises in holiday services for the disabled, ranging from tours to the hiring of adapted transport. It can even arrange romantic Italian weddings. This is the best first port of call.

+378 94 11 11; www.accessibleitaly.com) A San Marino—based company that specialises in holiday services for the disabled, ranging from tours to the hiring of adapted transport. It can even arrange romantic Italian weddings. This is the best first port of call. - Consorzio Cooperative Integrate (COIN;

within Italy 800 271027; www.coinsociale.it) Based in Rome, COIN is a great reference point for disabled travellers. It provides information on the capital (including transport and access) and is happy to share its contacts throughout Italy.

within Italy 800 271027; www.coinsociale.it) Based in Rome, COIN is a great reference point for disabled travellers. It provides information on the capital (including transport and access) and is happy to share its contacts throughout Italy. - Holiday Care (

0845 124 9971; www.holidaycare.org.uk) Has information on hotels with access for disabled guests, where to hire equipment and tour operators dealing with disabled travellers.

0845 124 9971; www.holidaycare.org.uk) Has information on hotels with access for disabled guests, where to hire equipment and tour operators dealing with disabled travellers.

You can also check out Tour in Umbria (www.tourinumbria.org) and Milano per Tutti (www.milanopertutti.it) for information on getting around those destinations.

Return to beginning of chapter

VISAS

Italy is one of 25 member countries of the Schengen Convention, under which 22 EU countries (all but Bulgaria, Cyprus, Ireland, Romania and the UK) plus Iceland, Norway and Switzerland have abolished permanent checks at common borders. For detailed information on the EU, including which countries are member states, visit http://europa.eu.int.

Legal residents of one Schengen country do not require a visa for another. Residents of 28 non-EU countries, including Australia, Brazil, Canada, Israel, Japan, New Zealand and the USA, do not require visas for tourist visits of up to 90 days (this list varies for those wanting to travel to the UK and Ireland).

All non-EU nationals (except those from Iceland, Norway and Switzerland) entering Italy for any reason other than tourism (such as study or work) should contact an Italian consulate, as they may need a specific visa. They should also have their passport stamped on entry as, without a stamp, they could encounter problems when trying to obtain a residence permit (permesso di soggiorno). If you enter the EU via another member state, get your passport stamped there.

The standard tourist visa is valid for up to 90 days. A Schengen visa issued by one Schengen country is generally valid for travel in other Schengen countries. However, individual Schengen countries may impose additional restrictions on certain nationalities. It is worth checking visa regulations with the consulate of each country you plan to visit.

You must apply for a Schengen visa in your country of residence. You can apply for only two Schengen visas in any 12-month period and they are not renewable inside Italy. If you are going to visit more than one Schengen country, you should apply for the visa at a consulate of your main destination country or the first country you intend to visit.

EU citizens do not require any permits to live or work in Italy but, after three months’ residence, are supposed to register themselves at the municipal registry office where they live and offer proof of work or sufficient funds to support themselves. Non-EU foreign citizens with five years’ continuous legal residence may apply for permanent residence.

Copies

All important documents (passport data page and visa page, credit cards, travel insurance policy, tickets, driver’s licence etc) should be photocopied before you leave home. Leave a copy with someone at home and keep one with you, separate from the originals.

Permesso di Soggiorno

Non-EU citizens planning to stay at the same address for more than one week are supposed to report to the police station to receive a permesso di soggiorno (a permit to remain in the country). Tourists staying in hotels are not required to do this.

A permesso di soggiorno only really becomes a necessity if you plan to study, work (legally) or live in Italy. Obtaining one is never a pleasant experience; it involves long queues and the frustration of arriving at the counter only to find you don’t have the necessary documents.

The exact requirements, like specific documents and marche da bollo (official stamps), can change. In general, you will need a valid passport (if possible containing a stamp with your date of entry into Italy), a special visa issued in your own country if you are planning to study (for non-EU citizens), four passport photos and proof of your ability to support yourself financially. You can apply at the ufficio stranieri (foreigners’ bureau) of the police station closest to where you’re staying.

EU citizens do not require a permesso di soggiorno.

Study Visas

Non-EU citizens who want to study at a university or language school in Italy must have a study visa. These can be obtained from your nearest Italian embassy or consulate. You will normally require confirmation of your enrolment, proof of payment of fees and adequate funds to support yourself. The visa covers only the period of the enrolment. This type of visa is renewable within Italy but, again, only with confirmation of ongoing enrolment and proof that you are able to support yourself (bank statements are preferred).

Return to beginning of chapter

VOLUNTEERING

- Concordia International Volunteer Projects (

01273 422218; www.concordia-iye.org.uk; 19 North St, Portslade, Brighton BN41 1DH, UK) Short-term community-based projects covering the environment, archaeology and the arts. You might find yourself working as a volunteer on a restoration project or in a nature reserve.

01273 422218; www.concordia-iye.org.uk; 19 North St, Portslade, Brighton BN41 1DH, UK) Short-term community-based projects covering the environment, archaeology and the arts. You might find yourself working as a volunteer on a restoration project or in a nature reserve. - European Youth Portal (http://europa.eu.int/youth/working/index_eu_en.html) Has various links suggesting volunteering options across Europe. Narrow down the search to Italy, where you will find more specific links on volunteering.

- Italian Association for Education, Exchanges & Intercultural Activities (AFSAI;

06 537 03 32; www.afsai.org; Viale dei Colli Portuensi 345, Rome) Financed by the EU, this voluntary program runs projects of six to 12 months for those aged between 16 and 25 years. Knowledge of Italian is required.

06 537 03 32; www.afsai.org; Viale dei Colli Portuensi 345, Rome) Financed by the EU, this voluntary program runs projects of six to 12 months for those aged between 16 and 25 years. Knowledge of Italian is required. - World Wide Organisation of Organic Farming (www.wwoof.it) For a membership fee of €25 this organisation provides a list of farms looking for volunteer workers.

Return to beginning of chapter

WOMEN TRAVELLERS

Italy is not a dangerous country for women to travel in. Clearly, as with anywhere in the world, women travelling alone need to take certain precautions and, in some parts of the country, be prepared for more than their fair share of unwanted attention. Eye-to-eye contact is the norm in Italy’s daily flirtatious interplay. Eye contact can become outright staring the further south you travel.

Lone women may find it difficult to remain alone. In many places, local Lotharios will try it on with exasperating insistence, which can be flattering or a pain. Foreign women are particular objects of male attention in tourist towns like Florence and more generally in the south. Usually the best response to undesired advances is to ignore them. If that doesn’t work, politely tell your interlocutors you’re waiting for your marito (husband) or fidanzato (boyfriend) and, if necessary, walk away. Avoid becoming aggressive as this may result in an unpleasant confrontation. If all else fails, approach the nearest member of the police.

Watch out for men with wandering hands on crowded buses. Either keep your back to the wall or make a loud fuss if someone starts fondling your behind. A loud ‘Che schifo!’ (How disgusting!) will usually do the trick. If a more serious incident occurs, report it to the police, who are then required to press charges.