Chapter 3 The Blended Learning Elements of Effectiveness

I feel that I like using technology to learn because you have this kind of independent feeling and you feel in control. I like this because we are learning and having fun and what’s learning without the fun?

—Fiona Lui Martin, 4th Grade

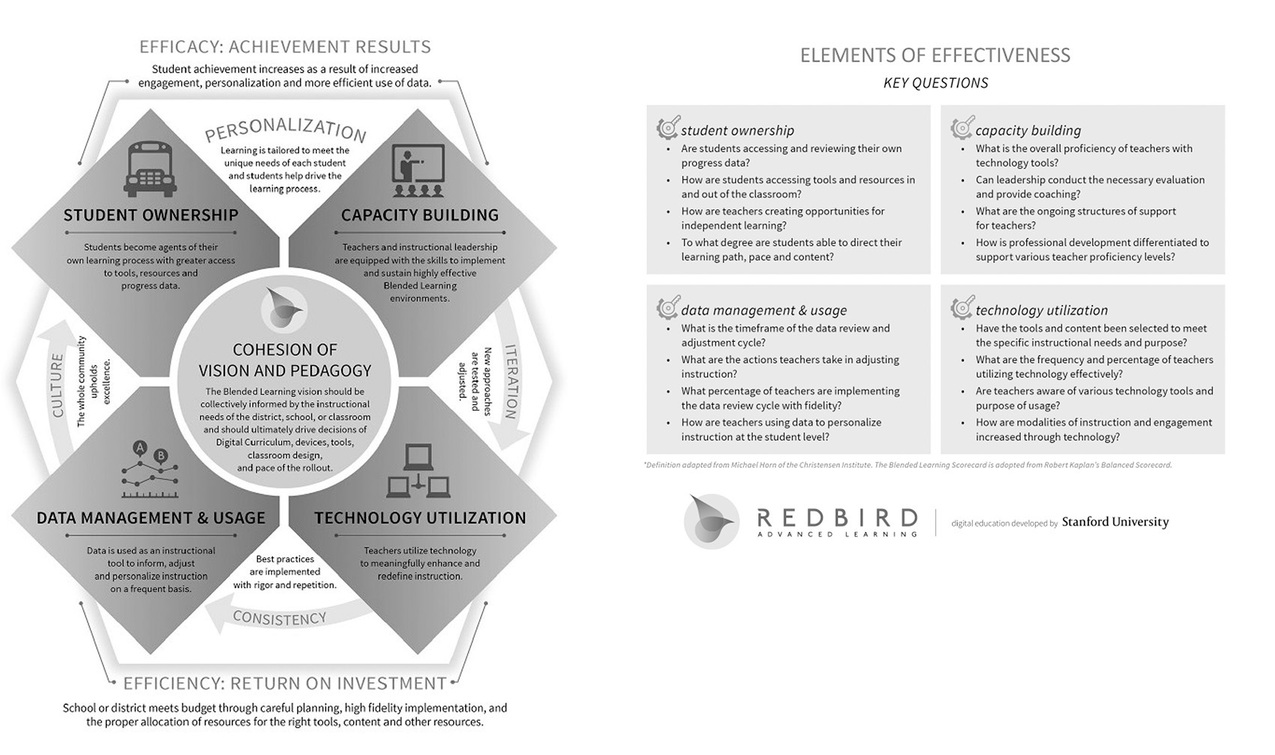

The Blended Learning Elements of Effectiveness tool pictured in Figure 3.1 (courtesy of Redbird Advanced Learning) codifies the essential elements of an effective blended learning initiative, helps ensure cohesion of planning and vision, and provides a tool for continued assessment and iteration. Similar to the empowerment evaluation model (Clinton & Hattie, 2014), the framework increases the capacity of stakeholders to “plan, implement, and evaluate their own programmes thus increasing the likelihood of success” (Hattie, 2015, p. 23). The Elements of Effectiveness tool is intentionally cyclical in nature, since the blended learning process is more iterative than linear and should continue to improve and build on itself as instructional staff become more proficient and obtain more data points about what is working at the district, school, and classroom level. Additionally, the process is interconnected in that each element impacts the others; however, there is a way to approach the process with some degree of sequence for planning and structure. The cycle progresses in the following order: 1. Visioning, 2. Capacity Building, 3. Technology Utilization, 4. Data Management, and 5. Student Ownership.

This chapter

- dissects the critical elements that ultimately drive the success or failure of a blended learning initiative; and

- emphasizes each element’s usefulness for instructional leadership to initiate and manage a comprehensive blended learning initiative.

Throughout the book, the Elements of Effectiveness are referenced and identified by icon, demonstrating the need to remain comprehensive in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of the initiative.

The Elements Described

Cohesion of Vision and Pedagogy

As discussed in Chapter 2, the blended learning initiative should start with a collective vision informed by the instructional needs of the district, school, or classroom. This vision should ultimately drive decisions of digital curriculum, devices, tools, classroom design, and pace of the rollout. Each blended learning model presents unique pedagogical opportunities. To achieve cohesion of school vision and pedagogy, school leaders should strive to match the teaching practices embedded in each model to the school’s academic goals and practices. For example, a school that prioritizes collaboration and project-based learning can find cohesion in a rotation station practice in which one of the stations is dedicated to small group projects.

Capacity Building: Teachers and Instructional Leadership Are Equipped With the Skills to Implement and Sustain Highly Effective Blended Environments

Fullan and Quinn describe collective capacity building as “the increased ability of educators at all levels of the system to make the instructional changes required to raise the bar and close the gap for all students” (Fullan & Quinn, 2016, p. 57). One of the greatest challenges of a blended learning initiative is that the teachers, leaders, and students are learning new skills together. This new paradigm can be very unsettling for instructional leaders and teachers, create anxiety, and even impede experimentation and innovation. On the other hand, Richardson in his Ted Talk explains, “People who model their own learning process [are able to] connect to other learners as a regular part of their day, and learn continuously around the things they have a passion for” (Richardson, 2012).

Through this opportunity for modeling in a blended learning initiative, the whole school becomes a learning community starting with three key behaviors:

- Honesty and humility—Admitting that you are all learning new skills, tools, and techniques together. This helps create a feeling of safety within the group and allows you to be more reachable for support.

- Becoming the lead learner—According to research conducted by Robinson, Lloyd, and Rowe (2008), the single greatest impact a school principal can have—by a factor of two—was to participate as a learner in professional development with staff in helping to move the school forward.

- Establishing and maintaining structures of support—This is one of the most important areas where an instructional leader can best support teachers, especially as you are learning together. In the same way, a practicing blended learning teacher becomes a facilitator of learning and not a holder of knowledge, by establishing structures of support you are reducing the need to be the expert of all things blended learning, and helping to ensure that there are structures in place for teachers to continue learning independently and collectively. These types of structures are covered in more detail later in Chapter 4.

Capacity building is the foundation of the blended learning initiative because it develops the culture; accelerates the speed of the change; fosters sustainability; and reinforces the strategy (Fullan & Quinn, 2016).

Links to the Classroom: Building Student Capacity

Taking the time to build technology skills for students is similarly important. The erroneous assumption that teachers sometimes make is that being a digital native means students will pick things up easily and/or without training. Most digital natives have learned to use technology in very specific ways, typically with respect to consumption and social interaction. The reality is that students need just as much onboarding into new technology environments as the teachers, especially as it relates to using technology for instructional purposes. Strategies for onboarding students effectively are covered in Chapter 8.

Technology Utilization: Technology Is Used to Meaningfully Enhance and Redefine Instruction

The presence of technology does not equate to meaningful use or impact in the classroom. A thoughtful approach to the specific technology chosen and how it is deployed is critical. In Chapters 5, 6, and 8 we go into more detail regarding the selection and deployment of the right technology based on pedagogy, learning goals, budget, and other constraints. With adequate capacity building, teachers should be in position to identify and use technology tools to meet their instructional needs. Consequently, this becomes their technology toolbox (Chapter 5).

Links to the Classroom: Getting Creative With Limited Resources

Faced with a frustrating lack of resources and technology, many teachers work creatively to implement blended practices where possible, even without the ideal tools to do the job. If you are teaching in a school where devices and tools are not provided for students, then the question becomes whether personal devices can be leveraged to help students get connected. This may be possible in the following ways:

- Embracing a BYOD (Bring Your Own Device) practice in your class

- Using more blended tools as homework or for out of school activities

- Educating students about local public Wi-Fi access points, such as libraries or cafes

- Connecting low-income families with programs that offer discounted devices and internet

- Engaging local community partners to donate devices

However, it is always important to provide choice for students to work offline if relying on personal access, since unfortunately many students do not have Wi-Fi or device access outside of school.

Data Management and Usage: Data Is Used as an Instructional Tool to Inform, Adjust, and Personalize Instruction on a Frequent Basis

Since leveraging formative data to adjust and personalize instruction is one of the greatest benefits of an effective blended learning initiative, the majority of the data conversation in this book is dedicated to formative assessments. The emergence of technology in classes presents an unprecedented opportunity for teachers to not only obtain data on a more frequent basis, but also to analyze that data, and use it to adjust instruction accordingly. A high-performing blended learning classroom should strive to achieve ongoing data collection and incorporate instructional adjustments at the student level. Furthermore, the type and scope of data obtained can be more holistic thus helping a teacher increase personalization (Chapter 7).

Student Ownership: Students Become Agents of Their Own Learning Process With Greater Access to Tools, Resources, and Progress Data

The height of a blended learning initiative is when the student (or learner) takes ownership of their learning process. However, this doesn’t mean that teachers aren’t involved. In fact, research shows significant impact on learning when high expectations are set by teachers (Rubie-Davies, 2015) combined with support and opportunities for personalized learning. Student ownership is a critical component of personalization in which “learners first understand how they learn best. Then they acquire the skills to choose and use the tools that work best for their learning qualities” (Bray & McClaskey, 2013, p. 15).

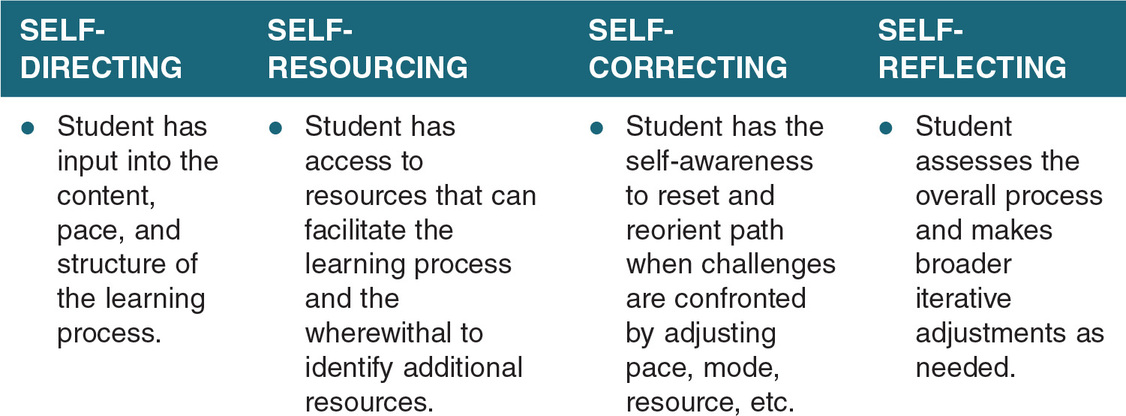

Student ownership occurs when the learner actually becomes a self-directing, self-resourcing, self-correcting, and self-reflecting agent in their learning process, as illustrated in Figure 3.2 below. In this manner, the student is an ongoing contributor to the conversation of their learning. Ideally, as students matures they assume an increasing role in this process.

One of the greatest benefits of well integrated technology is that the traditional constraints of a classroom or teacher instruction are removed. Learning is no longer limited to a specific location or a finite amount of time. Through the use and availability of technology tools, students can learn anywhere, at any time, and at the pace and mode that fits their unique needs.

This is a new paradigm of learning that requires a shift in mindset of both the teacher (from lecturer to facilitator) and the student (from passive receiver to active owner). Greater detail on making these shifts is outlined in role definition tables and by the “student ownership” icon throughout the book.

Figure 3.2 The Student Ownership Paradigm

Wrapping It Up

The blended learning initiative must be viewed, planned, and implemented in a cohesive and comprehensive manner. The Blended Learning Elements of Effectiveness provide a framework so that schools can ensure that the elements critical to success are addressed and assessed. Leaders should view the Blended Learning Elements of Effectiveness as a tool for planning and continued iteration recognizing that the implementation will evolve over time.

Book Study Questions

- How would you describe the current proficiency and readiness of teachers in your school(s) as it relates to blended learning? Are there champions or leaders emerging?

- What are the structures of support that are already in place for building capacity of teachers in your school(s)? How can you leverage these existing supports in building capacity for blended learning?

- Which technology tools are currently available to your instructional staff? How effective is the current usage? What evaluation tools are in place or desired to better assess effectiveness?

- Describe the existing data culture in your school(s). How frequent are data cycles? Are teachers using data to adjust instruction on a personalized level?

- To what degree do students take ownership of their learning? What are some success stories of student ownership? How can these be replicated?