Chapter 3

The Great War

From Hope to Defeat

It was May 1913 when the dilettante Austrian artist first showed up in Munich. Leaving Vienna behind, as well as the embarrassment of his repeated failure to enter its Academy of Fine Arts, Hitler hoped to attend Munich’s art academy for a period of three years.1 Upon registering with the police in Munich, he listed his profession as Kunstmaler (painter).

The Dabbling Artist

During his time in the Austrian capital, Hitler relied mainly on watercolors, as they were less expensive than oil paints, to create intricate depictions of renowned landmarks. In Munich, some of Hitler’s preferred subjects were the famed beer hall, the Hofbräuhaus, and the Opera House. He would spend days working on his paintings before visiting art dealerships and popular bars to showcase his art. Hitler expressed his affection for Munich and felt right at home in the Bavarian capital, which had around six hundred thousand inhabitants at the time.

A firsthand account of Hitler in those early years is given by one of his first customers, Dr. Hans Schirmer. Sitting in the Hofbräuhaus Biergarten, he noted:

Around eight o’clock I noticed a very unassuming, quite shabby-looking young man, whom I took for an impoverished student, pass by my table offering to sell a small oil painting. Around ten o’clock I observed that he had still not managed to sell his painting. . . . At length I met his price. It was a mood piece, called Evening. As soon as the painter left me I noticed that he went to the buffet and bought a piece of bread and two Viennese sausages. He ate this alone, without any beer.2

Ineptitude at depicting the human form (the unschooled artist’s attempts at drawing people resembled stick figures) limited Hitler’s subjects to landscapes and buildings. Even with the help of his Munich roommate, who had accompanied him from Vienna, Hitler had very little success selling his work.

Unfit to Serve?

To make matters worse, in January 1914 Hitler received devastating news from Austria: the officials had tracked him down for having allegedly failed to report for military service in his homeland. Rejecting conscription in a peacetime army, he pleaded with the Austrian authorities, depicting himself as a down-and-out artist struggling to make a living in a city where “three thousand artists” were trying to get by. Hitler was, however, obliged to report to the authorities in Salzburg, where, after he failed his physical, the Austrian officials took pity on him and deemed him unfit to serve.3 Soon after, Hitler’s luck improved as he found more buyers for his inexpensive, run-of-the-mill artwork. He obviously abandoned his ambition of enrollment at Munich’s art academy and recalled in Mein Kampf that, at that time, “he was painting to live rather than living to paint.”4

Or Fit to Fight?

Adolf Hitler was thrilled when, a few months later, World War I broke out. He recalled the opportunity it presented to him: “Even today, I am not ashamed to say that, overcome with rapturous enthusiasm, I fell to my knees and thanked heaven from an overflowing heart for granting me the good fortune of being allowed to live at this time.” In his mind, the war at hand represented the realization of the Greater Germany he had dreamed of since youth.

As the country mobilized for war, excitement swept through Germany, with many embracing the idea of going to battle. The belief that war would bring national unity and the opportunity for the German Empire to assert its power in Europe played a key role in this enthusiasm. A sense of national pride, coupled with the desire to defend Germany’s perceived place in the international order, fueled the eagerness of many Germans to go to war. The idea that a conflict with France and Russia could lead to the reclaiming of lost territory and the expansion of the German Empire also contributed to the fervor. This was not a result of individual reasoning but rather a mass outpouring of emotions, as large gatherings saw people close to hysteria and willing to make sacrifices for the “cause.” The idea of a pan-Germanic nation, with a master race directing the progress of mankind, was also a popular sentiment. Although such statements may have been echoed by an older Adolf Hitler, at that time he was merely eager to join the Bavarian armed forces.

On the fateful day of August 3, 1914, Germany declared war against France, and Hitler was filled with excitement and eagerness to play his part in the conflict. Just half a year after the Austrian army had deemed Hitler “unfit to serve,” he now submitted a personal petition to King Ludwig III of Bavaria, asking to join the army as a volunteer. To Hitler’s delight, his request was granted, and he was accepted into the 2nd Bavarian Infantry Regiment. This was a significant moment for Hitler, as he was now free to fight under the German flag instead of the Austrian, which he had grown to dislike. Joining the army also meant he no longer had to worry about paying for his basic needs such as food, clothing, and shelter. Hitler had finally found a purpose in life and was determined to play his part in the grand scheme of things.

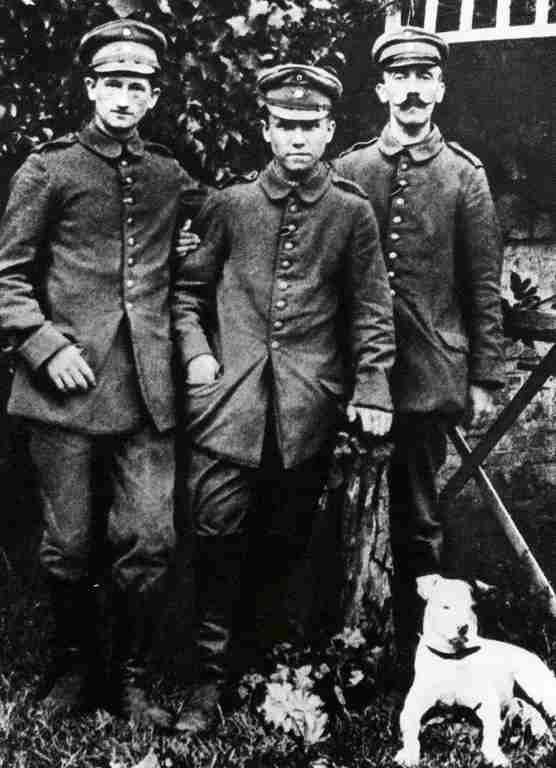

After several months of basic military training at the Munich barracks, Hitler, now wearing a uniform and armed with a rifle, took an oath of loyalty to King Ludwig III in person, as well as to Emperor Wilhelm in absentia. He then joined his regiment and embarked on a journey that began with a seventy-mile march through the rain to Lerchfeld Camp for further, more intense training. Eventually, Hitler and his comrades were shipped off to the front lines, where they soon found themselves thrown into the hellhole of battle near Ypres in Belgium.

Of Mud and Medals

“Private” Hitler was now faced with the well-known horrors of World War I warfare: vast expanses of mud-filled craters, barbed-wire defenses, concealed landmines, rat-infested water-filled trenches, and persistent deadly assaults. In his first battle, Hitler served as a regimental dispatch carrier and, under heavy enemy fire, assisted in retrieving a wounded lieutenant colonel with the help of a medic.

In November 1914, Hitler’s regiment underwent significant reductions in personnel. While serving with the new commander, Lieutenant Colonel Engelhardt, Hitler and another enlisted soldier embarked on a perilous mission near the front lines to observe the enemy’s position. Their presence was detected, and they were met with an unexpected burst of machine-gun fire. Hitler and his comrade acted quickly, shielding the commander and pushing him into a ditch. The lieutenant colonel silently shook their hands in gratitude. Later, Hitler was awarded the Iron Cross Second Class, a medal typically reserved for soldiers who demonstrate exceptional bravery in combat. He was also promoted to corporal for his willingness to aid injured soldiers and undertake dangerous missions, establishing himself as a dependable and trustworthy soldier.

During the trench warfare in Ypres, Hitler had the opportunity to indulge in his artistic pursuits. He had brought some art supplies with him and, when the opportunity arose, created drawings and watercolors. This hobby made him popular among his fellow soldiers, who enjoyed seeing their experiences and memories captured in his sketches and cartoons. When more serious topics arose in their conversations, Hitler would passionately share his opinions on topics such as art, architecture, and politics, impressing his comrades with his fluency and knowledge. Despite being more reserved when the topic turned to food or women, Hitler was admired for his ability to engage in thoughtful discussions.

By the end of summer 1915, Hitler had established himself as a valuable asset to his regiment’s officers. As communication lines were constantly incurring damage from enemy artillery, trustworthy human messengers became crucial to military operations. Hitler demonstrated his daring and stealth by quietly crawling to the front lines, much like he used to do in his childhood Indian games. In September, when the British made a night advance that threatened Hitler’s entire regiment and disrupted the phone lines, he ventured out with another soldier to gather information on the enemy. Despite the dangerous mission, they were able to make it back “by the skin of their teeth.”5

Throughout the years on the front, time and time again, as if by miracle, Hitler managed to narrowly escape death. He once recounted to an English correspondent,

I was eating my dinner in a trench with several comrades. Suddenly a voice seemed to be saying to me, “Get up and go over there.” The command was so clear and insistent that I obeyed mechanically, as if it had been a military order. I rose to my feet at once and walked twenty meters along the trench, carrying my dinner in its tin-can with me. Then I sat down to go on eating, my mind being once more at rest. Hardly had I done so, than a flash and deafening report came from the part of the trench I had just left. A stray shell had burst over the group in which I had just been sitting, and every member of it was killed.

During the course of World War I, Hitler was fortunate in many ways, but he also suffered two injuries: one from an exploding shell and another from a gas attack that temporarily caused him blindness. Hitler also received a second award, the Iron Cross First Class in 1918, for his bravery in an open warfare attack, where messengers played a crucial role.

World War I brought immense hardship not just to soldiers but also to the German civilian population. With food shortages, many people were reduced to eating dogs and cats, and bread made from sawdust and potato peels was common. Strikes erupted, fueled not only by hunger but also by Germany’s inability to reach a peace agreement with Russia’s newly established Bolshevik government. In January 1918, the situation reached a breaking point as workers across Germany went on strike, calling for workers’ representation in negotiations with the Allies, increased food rations, the removal of martial law, and a nationwide democratic government. Upon hearing of these events, Hitler blamed the lack of action on “lazy workers” and the Communists. This is “the biggest piece of chicanery in the whole war,” he grumbled. “What was the army fighting for if the homeland itself no longer desired victory? For whom the immense sacrifices and privations? The soldier is expected to fight for victory and the homeland goes on strike against it!”6

It was during Hitler’s hospital stay to recover from the effects of mustard gas that the announcement of President Wilson’s ultimatum was broadcast, requiring Kaiser Wilhelm’s resignation before an armistice would be accepted. The ultimatum led to the breakdown of Germany’s military and a mutiny among the sailors, snowballing into revolution. This marked a pivotal moment in Germany’s involvement in World War I, culminating in the signing of the Armistice and, later, the infamous Versailles Treaty. As Hitler sat in his barracks in Munich, he pondered his uncertain future. After four years of serving Germany, what lay ahead for him in civilian life? Would Adolf Hitler resume his failed art career, or would destiny proffer an unexpected path?

Notes

1. Frederic Spotts, Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics (London: Hutchinson, 2002), 129.

2. Hans Schirmer, Niederschrift im Hauptarchiv der NSDAP, reel 2, file 30.

3. Spotts, Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics, 131.

4. Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans. Ralph Manheim (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1971), 126.

5. Toland, Adolf Hitler, 63.

6. Ibid., 69.