Chapter 5

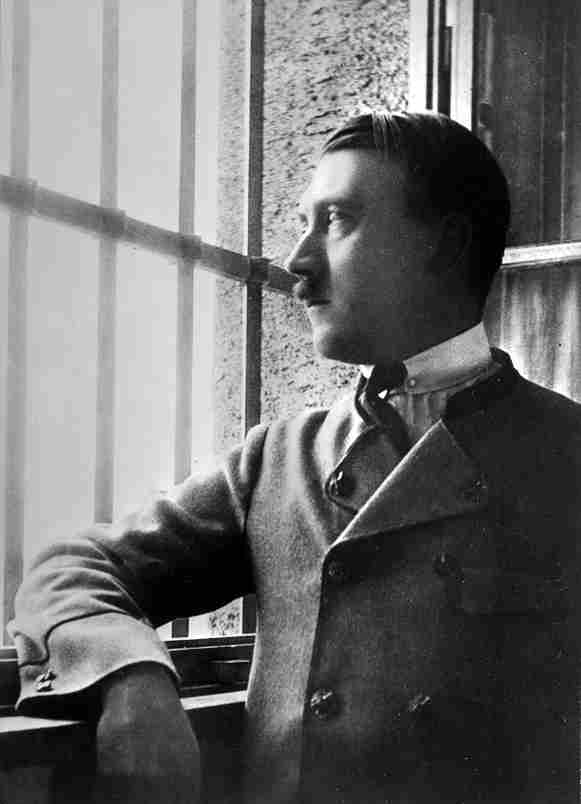

From Soldier to Führer

In order to better grasp how Hitler shaped his National Socialist views, it is important to take into account the dramatic events that took place in Munich in 1918 and 1919. Considering Bavaria’s moderate and conservative political tradition, it probably came as a shock to most Germans to learn of Kurt Eisner’s coup d’état and its ensuing left-wing revolution.

The Peoples’ Republic of Bavaria

Eisner, a Jewish politician, journalist, and leader of the centrist USPD (Independent Social Democratic Party), became the first republican head of government in Bavaria. Though the November revolution of 1918 first emerged in Munich, it spread through Germany like wildfire and resulted in toppling monarchic leadership and even the emperor himself. In hindsight, the revolution of 1918 was not a move toward social or political reform as much as it was a direct rebellion against the war. During the weeks leading up to the Bavarian uprising, a deep longing for peace at any price could clearly be discerned.

Regardless of justifications for the revolution, many were those in Bavaria who fiercely denounced the new government as being run by Jews: even worse—by non-Bavarian Jews (Eisner hailed from Berlin). Over the next few months, it became apparent that the feeling of discontent in Bavaria was not a result of the new leader’s goals but, rather, that the revolution had put an end to Bavaria’s institutions and political traditions.1

Eisner’s ascent to power coincided with the November 11 Armistice, a cease-fire that led most Germans to believe erroneously that they had won the Great War. The truce, however, did not lift the ongoing international blockade aimed at punishing the German people. Though the war had come to an end, the borders remained closed and hunger persisted. Worse than the Allied blockade was that Kurt Eisner, for all that he aspired to represent, possessed no governing skills and hadn’t the faintest clue as to the workings of high politics or how to inspire and lead the Bavarian people.

The Bavarian Soviet Republic

Following the Armistice, Hitler decided to remain in the army, conceivably for financial reasons, as well as possibly due to the fact that he had neither family nor friends to whom he might return.2 Ironically, the defense of Eisner’s new regime against antisemitic attacks fells to the 2nd Infantry Regiment to which Hitler belonged at war’s end. This responsibility was obviously not implemented effectively enough to protect Eisner from armed attack. Only two days after a failed coup led by a sailor, Eisner was assassinated on February 21, 1919. Earlier that year, his party had gleaned a pitiful 2.5 percent of the votes in the state election.

The assassination of Eisner paved the way for the radical left’s fast-growing movement to undermine parliamentary democracy and seize control. In just a few days, a fresh surge of revolutionary zeal swept through the Bavarian capital. Red flags were flown, martial law was enforced, and a new administration was established. This new government was headed by Ernst Niekisch, a left-wing social democrat who espoused National Bolshevism, advocating for Germany’s future to be tied with the East, specifically, through collaboration with Russia.

Hitler’s superiors recognized his remarkable oratory skills and appointed him to act as an intermediary between his regiment’s propaganda department and the revolutionary regime. Officially designated as a Vertrauensmann (man of confidence) of his company, Hitler underwent a transformation from an obedient soldier, a solitary figure, and a wanderer to a respected leader of others by April 1919.3 Despite the proclamation of a “Soviet Republic” in Bavaria, Hitler chose to remain stationed at his army headquarters, presumably hoping to weather the storm. If he had deserted the army and rejected the Communist revolutionary regime, he may have had to give up the relative comfort and stability of his new position. Notwithstanding the widespread opposition to the Bavarian Communist Soviet Republic, Hitler continued to interact with the Communist regime and was elected deputy battalion councilor for his unit.

In theory, Munich’s military units, including Hitler’s, were part of the Communist regime’s “Red Army.” For the greater part, though, the military did not support the Soviet government and attempted to remain neutral at all costs: Hitler was among those who did not join active units of the Red Army. By the end of April 1919, the thirty to forty thousand troops of the government in exile (which had meanwhile retreated to Bamberg) stormed Munich. Though mass desertion took place among members of the Red Army, Hitler, who chose not to defect, was taken prisoner and detained for a short time by the “white” troops.

The Rise of Antisemitism and Anti-Bolshevism

The brief existence of Munich’s Soviet Republic resulted in a dramatic surge in antisemitism. This form of xenophobia did not target all Jews equally, in the manner that National Socialist antisemitism would later develop. Instead, it was primarily directed at Jewish revolutionaries and was expressed through anti-Bolshevik antisemitism, particularly aimed at political activists such as Eisner. In addition, Munich’s antisemitism assumed a religious character, with the Catholic Church openly denouncing all non-Catholic religious customs.4 Hitler’s experiences with revolution and the Soviet Republic in Munich are thought to have exacerbated his already active hatred for anything foreign, international, Bolshevik, and Jewish, which may have originated during his time in Vienna.

Following the reinstatement of democracy in Munich, the armed forces turned their attention to removing rebels and revolutionaries in order to prevent the resurgence of left-wing extremism. They singled out for retribution any military personnel who had fervently backed the Soviet Republic in Bavaria. Hitler saw this as a significant chance to offer his services as an informant. From May 1919, he served on a three-member board and carried out operations to identify soldiers who had served in the Red Army before being discharged.

The military leadership conducted propaganda classes in southern Bavaria to propagate counter-revolutionary notions, and Adolf Hitler and other officers attended them. The classes featured knowledgeable speakers on subjects such as history, economics, and politics, emphasizing the notion that ideas, not material conditions, shape the world. The course curriculum dealt with themes such as resource management for survival and the devastation caused to society by international capitalism and finance, seen as the fundamental causes of inequality and suffering. This final message, coupled with the classes’ anti-Bolshevik agenda, would have a profound and long-lasting impact on Hitler.

Hitler’s Mentor Karl Mayr

It fell to the propaganda department’s head, Captain Karl Mayr, to set up courses that would not only help Hitler shape his political views but led him to realize that he possessed oratory skills and could capture the listener’s attention. Karl Mayr was a General Staff officer and Adolf Hitler’s immediate superior in the Army Intelligence Division in the Reichswehr, to which Hitler now belonged. Mayr would later be known as the person who introduced Hitler to politics, as well as becoming his first mentor. In 1919, Mayr directed Hitler to write the so-called Gemlich letter, in which he first expressed his antisemitic views in writing.

kKarl Mayr produced pamphlets that were distributed to troops throughout Bavaria, covering a wide range in their political orientation. One of the pamphlets, titled “What You Should Know about Bolshevism,” was aimed at proving that “leaders of Bolshevism are chiefly Jews who ply their dirty trade.” Others showed up a dark side of communism or were written with the aim of appealing to Catholics or to members of the Socialist Democratic Party.5

It was at precisely this time, in early July 1919, that Germany was forced to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, a history-making event that would give Hitler an incentive to become active in the country’s politics. The Armistice of November 11, 1918, had brought an end to the fighting of World War I, but it was not until June 1919 that the Allies declared that war would resume if the German government did not sign the treaty they had agreed to among themselves. One of the most significant and contentious provisions of the treaty was the so-called War Guilt Clause, which stated that Germany and its allies accepted responsibility for causing all the losses and damages suffered by the Allied countries and their citizens as a result of the war. The treaty also required Germany to disarm, cede territory, and pay reparations to the Allied Powers. Some Allied leaders viewed these sanctions as excessive and counterproductive, while others, including French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, believed that, on the contrary, the treaty was too lenient on Germany.

In Munich, the peace terms were perceived as excessively harsh, and the Allied Powers’ decision to exclude the Provisional National Assembly of German Austria from the peace negotiations and deny Austria the right to self-determination was also controversial. It is very likely that Hitler, among others, anticipated that the international humiliation of Germany and the crushing of national pride would fuel a desire for revenge among the German people. Hitler would always view the events of November 1918 as the root of all Germany’s problems. He spent the rest of his life revisiting Germany’s defeat and trying to prevent a similar disgrace from occurring again. At this time, Hitler selected the parts of the course that resonated with him and simply discarded the rest. As a result, the societal and political ideas that began to form in his mind included the celebration of work, how to ensure a steady food supply for the population, the rejection of Bolshevism, and the elimination of the influence of international finance and capitalism.6

The propaganda courses completed, Hitler began working for Captain Mayr, who was only six years his senior. Born in Bavarian Swabia and the son of a judge, Mayr was raised in a Catholic middle-class family, had seen considerable action in the war, and had suffered a bad injury. Following his service on the western front, on the alpine front, in the Balkans, as well as in the Ottoman Empire, he was perceived by his commanders as a “highly talented, versatile officer of extraordinary intellectual vitality.”7

Back in Munich after the war, Mayr served first in the Ministry of War and ended, finally, as a company commander of the 1st Infantry Regiment, at the heart of which he actively fought, from within, against the short-lived Communist regime. Mayr’s goal was to shape the small group of army veterans who worked for him into representatives and propagators of his political vision. He considered himself a teacher and mentor to these men, despite plenty of opposition and disapproval on behalf of Munich’s civilian and military authorities. Though for a few short years Karl Mayr served as Hitler’s first mentor, he would gradually turn against Hitler’s policies and the future National Socialist Party. As a result, he was eventually interned in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp and, later, in the Buchenwald camp. A British bomb killed him while he was working at a nearby munitions factory in Weimar, just three months before the end of World War II.

Hitler Joins the German Workers’ Party

Following his activities as a speaker for the army’s propaganda department in Munich’s postrevolutionary period, Hitler was given the task of discretely attending meetings of various groups, especially those of a political nature. As a trusted political agent of the army, he was now to spy on and provide a report on one of Munich’s budding political parties, the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (DAP) or German Workers’ Party. After listening to a talk by Baumann, the chairman of the Bürgerverein who advocated for Bavarian separatism, Hitler felt compelled to stand up and deliver an impassioned speech in which he argued that all ethnic Germans should be united under one national roof. Later that evening, the tiny party’s cofounder and chairman, Anton Drexler, handed Hitler a pamphlet and asked him if he’d return in a week’s time. When Hitler read Drexler’s manifesto, he felt a strong connection to the ideas it expressed and claimed that he and Drexler had, over the years, experienced a similar political transformation.

Through his propaganda classes, Hitler had been exposed to the idea that Jews were seen by many as having contributed to Germany’s recent defeat. At this time, Hitler’s hatred of Jews was primarily directed at their role in capitalism, rather than at their involvement with Bolshevism. Drexler, who shared Hitler’s views, believed that Jewish finance capitalism was driving capitalist internationalism and that international socialism was being used by Jewish bankers to destroy and take over nations.

In a letter penned that year, Hitler exposed in no uncertain terms what he felt about Jews. He spoke about the “pernicious effect that Jews as a whole, consciously or unconsciously, have on our nation.” He added that Jews acted like “leeches” and that “Jewry is absolutely a race and not a religious community.” Furthermore, he believed that Jewish materialism caused the “racial tuberculosis of the nations” because Jews corrupted the character of their hosts. Hitler’s solution was, rather than carry out pogroms against Jews, that governments should limit the rights of the Jews and ultimately remove Jews altogether from their host nations.8

In the course of Hitler’s propaganda-fueled discourses to the soldiers, his oratory skills had been perceived as “spirited lectures . . . that included examples taken from life,” and he was acclaimed as “a natural speaker for the people, whose fanaticism and popular demeanor force his listeners in a rally to pay attention to him and to follow his thoughts.”9 Now, as he began to address groups of civilians, Hitler’s newfound radical antisemitism and racism did not, however, form the core of his political message but merely aspects of his Weltanschauung. Foremost on Hitler’s political agenda was to build a state that could avoid any future German defeat.

After accepting Drexler’s invitation to attend German Workers’ Party (DAP) meetings, Hitler became a member of the executive committee, serving specifically as a propagandist.10 The DAP, led by Drexler, aimed to convert the working class from Marxism and recruit members to support the Pan-German movement. As a publicist and spokesperson for the party, Hitler was motivated to leave the army and dedicate himself to political agitation. His oratory skills were largely attributed to his ability to connect with his audience’s desires and sentiments, employing simple and direct language, emotive slogans, and powerful rhetoric. Many noted that he spoke from the heart and shared his personal hopes and fears with those in attendance.

Eckart, the Antisemitic Author

Johann Dietrich Eckart, born in 1868 in Bavaria, was overly enthused to meet Adolf Hitler at a German Workers’ Party speech that the future Führer delivered in 1919. The year before, in December 1918,11 Eckart founded, published, and edited the antisemitic weekly Auf gut Deutsch (In Plain German). This was made possible with financial assistance from the Thule Society,12 as well as with the input of Alfred Rosenberg, whom Eckart called his “co-warrior against Jerusalem,”13 an antisemitist who eventually became the “ideologist” of the National Socialist Party.

Though his membership in the organization has long been the subject of experts’ debate, Eckart was known, at the very least, to have had occasional involvement in the Thule Society, a Munich occult study group promoting a political agenda. This Pan-German, völkisch, and antisemitic sect with roots in the prewar Germanic Order, named itself after Thule (Iceland), supposedly the symbol of Aryan purity. The members’ objective was to research the origins of German antiquity and the roots of the German race. The order’s logo was a stylized form of the swastika, an ancient symbol that was in use in numerous cultures for over five thousand years before Adolf Hitler adopted it as the centerpiece of the National Socialist flag. Signifying good fortune in Sanskrit, the swastika had already been adopted by several European organizations even prior to World War I. Among the Thule Society’s members were some who would later become active in high positions in the National Socialist Party: Rudolf Hess (secretary and successor to the Führer), Alfred Rosenberg (party ideology chief), and Hans Frank (head of the General Government in National Socialist–occupied Poland during World War II).

The antisemitic members of the Thule Society studied the occult and believed in the coming of a “German Messiah” who would redeem the nation after its defeat in World War I.14 Eckart expressed his anticipation in a poem he wrote months before he first met Hitler, in which he refers to the “Great One,” the “Nameless One,” or “Whom all can sense but no one saw.” When Eckart met Hitler, he was convinced that he had encountered the prophesied redeemer.15

Serving as a blueprint for Hitler’s later political doctrine, Eckart’s Weltanschauung heftily criticized the German Revolution and the Weimar Republic, deplored the Treaty of Versailles—which the author equated to treason—and believed in the widely propagated “stabbed in the back” legend that blamed the Jews and the Social Democrats for Germany’s defeat in World War I. Eckart also became the first publisher of the party’s newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter, a paper that the NSDAP later purchased from the Thule Society.

In early 1923, as a result of Eckart’s publication of a libelous poem deriding Germany’s president, Friedrich Ebert, he escaped arrest by hiding out, under the name of Dr. Hoffman, in the Bavarian Alps near Berchtesgaden, close to the German-Austrian border. It was there that Hitler paid him a visit in the spring, a sojourn that served to introduce the future Führer to the area where he would later build his home and Alpine headquarters, the Berghof at Obersalzberg.

Twenty-one years Hitler’s senior, Eckart would greatly contribute to the creation of the future dictator’s public persona16 as well as the Hitler Myth.17 Beyond their common political opinions, a deep emotional and intellectual bond developed between the two men,18 and in private Hitler later acknowledged Eckart as having been his teacher and mentor19 and the spiritual cofounder of National Socialism.20 As Hitler’s early guide, Eckart exchanged ideas with him and helped to establish the theories and beliefs of the party.21 He lent Hitler books to read, gave him a trench coat to wear, and made corrections to Hitler’s style of speaking and writing22 and taught him proper manners.23

The two men found many interests in common, in particular in the fields of art and politics, and Eckart introduced Hitler to the painter Max Zaeper and his salon of like-minded antisemitic artists, as well as to the photographer Heinrich Hoffmann, who became instrumental in marketing the Hitler Myth.24 Using his connections within the völkisch movements,25 Dietrich Eckart facilitated meetings between Adolf Hitler and affluent potential donors. Collaboratively, the duo endeavored to gather funds for the German Workers’ Party in Munich.26 However, their efforts proved futile in the beginning. On the other hand, Eckart was better connected with the rich and powerful in Berlin, where the two party campaigners managed to collect substantial funds. On one such visit to the capital, Eckart introduced Hitler to his future etiquette tutor, socialite Helene Bechstein, thanks to whom Hitler began to mingle among the upper circles of Berlin’s high society.27 Eckart also made recommendations to Hitler as to who should assist him within the party, bringing the likes of Julius Streicher on board, the publisher of the virulently antisemitic Der Stürmer.

Later, Hitler would dedicate part two of his book Mein Kampf to his former friend and mentor, and named a hospital, a stadium, and a school after him. Hitler told one of his secretaries that his friendship with Eckart was “one of the best things he experienced in the 1920s” and that he never again had a friend with whom he felt such “a harmony of thinking and feeling.”28

The Appeal of the Party

One of the key factors that contributed to the success and growth of the German Workers’ Party, later renamed the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), was its perception of itself as a movement rather than a political party. The idea of a party connoted loyalty to parliamentary democracy, whereas Hitler promoted the National Socialist “movement,” a term that evoked a sense of energy and progression toward a shared objective. On February 24, 1920, Hitler and Drexler drew up an official twenty-five-point program for the fledgling movement that called for the revocation of the Versailles Treaty, the “union of all Germans in a Greater Germany,” and the denial of civil rights for Jews, among other items. By July of the next year, Hitler had insisted on becoming the NSDAP’s chairman “with dictatorial powers.” Having gained complete control over the National Socialist Party, Hitler could now implement his propaganda campaign.

Over the next couple of years, Hitler’s movement drew a lot of attention, not only through its leader’s regular inflammatory speeches but because of repeated violent outbreaks between the NSDAP’s ruffians and members of competing groups and parties on the streets of Munich. This function of protecting Hitler and other National Socialist leaders or being aggressive toward the opposition fell into the hands of Ernst Röhm, a Free Corps veteran with a penchant for ruthless violence, in the form of the Sturmabteilung (Storm Division), better known as the SA.

The Munich Putsch

Mussolini’s “March on Rome” in late October 1922 inspired Hitler’s so-called Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch. On November 8, 1923, with a crowd of over two thousand supporters, Hitler endeavored to overthrow the government. The plan was first to seize the Bavarian government before marching on Berlin to overthrow the Weimar Republic. The key figures in the uprising were Adolf Hitler, World War I veteran Hermann Göring, Ludwig Siebert (the leader of another right-wing group), and Ernst Röhm, with close to two thousand members of his SA fighters.

The uprising was quashed by the police and army. Subsequently, Hitler was arrested and tried for high treason in a Munich court starting from February 26, 1924, with the trial lasting for twenty-four days. During the proceedings, Hitler exploited the opportunity to propagate his nationalist and antisemitic views and gain public attention. He acted as his own defense counsel and delivered speeches blaming the government and Jews for Germany’s defeat in World War I and for its economic woes. Hitler also contended that the putsch was not a criminal offense but a move to protect Germany from the Communists and Jews.

Hitler’s speeches at the trial were reported in the newspapers, catapulting him to widespread public attention. Nevertheless, he was found guilty of high treason and handed a five-year prison sentence. However, he served a mere nine months of his term in Landsberg Prison, where he dictated the first volume of his book Mein Kampf (My Struggle) to his deputy Rudolf Hess. Ultimately, the trial and Hitler’s defense speeches played a crucial role in his eventual rise to power, as it helped him to gain considerable public notice and promote his ideas.

The Written Word

As Hitler was forbidden to speak in public for four years, he devoted this time to resurrect the National Socialist Party by writing articles for the party’s press. He also set in motion the party’s propaganda directorate, with Gregor Strasser as its head, assisted by Heinrich Himmler.29 Julius Streicher, the Nuremberg Party Leader, and Party Leader Joseph Goebbels in Berlin were each responsible for inflammatory newspapers that greatly contributed to the dissemination of propaganda material.

The NS Propaganda Directorate launched a nationwide campaign of recruitment through carefully designed leaflets, pamphlets, and posters. The propagandists established precise guidelines regarding the organizing of meetings as well as the design, color, and wording of visual advertising. They focused on simple messages such as “Work and Bread,” and unlike their political adversaries, they promoted the persona of the party leader, Adolf Hitler. The Propaganda Directorate “carefully crafted images of the Führer that emphasized his charisma, his roots among the common people, his heroism as a soldier in World War I, his quasi-messianic nature as a savior, and his respectability.”30

Targeting the Masses

Though in the campaigning years Hitler and his followers generally banged away at Liberals, Communists, Social Democrats, and Jews, Hitler’s antisemitic jibes were toned down after 1928 as his party began to see a strong increase in general support and because he realized that he needed to gain respectability as a future national leader.31

In the party’s fourteen-year-long electoral campaign, violence walked hand in hand with propaganda. Recurrent bloody outbreaks took place between the NSDAP’s ruffians and members of competing groups and parties on the streets of Munich and elsewhere in Germany. The function of protecting Hitler and other National Socialist leaders or aggressing the opposition fell upon Ernst Röhm and the SA.

The SA storm troopers were repeatedly responsible for bloody—even fatal—clashes with the paramilitary organizations of the Social Democrats and the Communists. National Socialist media often presented this violence as self-defense or as heroic battles against the “Marxists” who otherwise would lead to a “Bolshevist” Germany.

In 1930, Hitler named Goebbels director of the party’s national propaganda apparatus. Known for his fiery oratory and loyalty to the Führer, Goebbels organized the election campaigns of 1930 and 1932, including the slogan “Hitler over Germany.” This novel marketing sensation consisted of chartering a plane to fly Hitler all over the country. His propagandists arranged for Hitler to speak at some twenty rallies, “electrifying” nearly one million Germans. Goebbels pioneered the use of radio and, as an inveterate film buff, ordered the production of motion pictures of rallies, speeches, and other events to show at meetings with the aim of further inspiring and mobilizing core supporters.32

Voters had varying reasons to cast 33.7 percent of votes for Hitler and his party in the November 6, 1932, elections, a couple of months before he seized power. For the most part, support for Hitler was not due to antisemitic reasons but, rather, in hopes of ending the ongoing economic crisis and the political division and disorder that Germans experienced under the Weimar Republic. In 1929, the U.S. stock market crash had triggered a wave of financial panic and a global economic downturn that initiated the Great Depression in Germany, a catastrophic turn of events that greatly exacerbated the nation’s already untenable financial devastation.

A large proportion of young people were drawn to the party because it came across as dynamic, heroic, and youthful, as opposed to the tired, old established parties. The National Socialists groomed their image as standing above class and confessional differences and as representing blue-collar and white-collar workers, peasants, soldiers, women, students, the middle class, Protestants, and Catholics.33

Thanks to propaganda, the National Socialists appeared as the only viable political alternative and the only way to save Germany. The party’s underlying antisemitism did not stop those millions of Germans from voting for the National Socialists.34 In general, most voters overlooked Hitler’s antisemitism, thinking that, given time, it would disappear or they disregarded it, as it did not “affect them.”

Hitler’s promise to restore the economy—as well as Germany’s national pride—along with numerous other alluring assurances touted by his political agenda did not fall on deaf ears. Years of National Socialist propaganda, coupled with Hitler’s often mesmerizing rhetoric, allowed the Third Reich to commandeer power in 1933. Few people foresaw then that this was not the dawning of a glorious “thousand-year Reich,” but the beginning of a twelve-year reign of terror.

Notes

1. Thomas Weber, Becoming Hitler: The Making of a Nazi (New York: Basic Books, 2017), 13.

2. Ibid., 10.

3. Ibid., 40.

4. Ibid., 58.

5. Ibid., 92.

6. Ibid., 82–86.

7. Ibid., 102.

8. Ibid., 119.

9. Sönke Neitzel and Harald Welzer, Soldaten: On Fighting, Killing, and Dying, trans. Jefferson S. Chase (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012), 122.

10. Ernst Dauerlein, Der Aufstieg der NSDAP in Augenzeugenberichten (Dusseldorf: Rauch, 1968), 98.

11. Ian Kershaw, Hitler: A Biography (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008), 154.

12. Volker Ullrich, Hitler: Ascent, 1889–1939, trans. Jefferson Chase (New York: Vintage, 2017), 105–7.

13. Toland, Adolf Hitler, 78.

14. John Michael Greer, The New Encyclopedia of the Occult (St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn, 2003), 322.

15. Claus Hant, Young Hitler (London: Quartet Books, 2010).

16. Ullrich, Hitler: Ascent, 105–107.

17. Joachim C. Fest, Hitler, trans. Richard Winston and Clara Winston (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1975), 136.

18. Weber, Becoming Hitler, 288.

19. Ibid., 143.

20. Karl Dietrich Bracher, The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure, and Effects of National Socialism, trans. Jean Steinberg (New York: Praeger, 1970), 119.

21. Kershaw, Hitler, 94–100.

22. Toland, Adolf Hitler, 99.

23. Fest, Hitler, 132–33.

24. Weber, Becoming Hitler, 142–43.

25. Ian Kershaw, Hitler: Profiles in Power (London: Routledge, 1991), 41.

26. Kershaw, Hitler, 155.

27. Weber, Becoming Hitler, 212–13.

28. Ullrich, Hitler: Ascent, 105–107.

29. Steven Luckert and Susan Bachrach, State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda (Washington, DC: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2009), 36–38.

30. Ibid., 39.

31. Sarah Gordon, Hitler, Germans, and the “Jewish Question” (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984), 69.

32. Luckert and Bachrach, State of Deception, 56–57.

33. Ibid., 48.

34. Christopher Browning, The Origins of the Final Solution (London: Arrow, 2004), 8.