Chapter 6

Hitler’s Swift Rise to Power

We struggle to grasp how a people who gave the world Luther, Bach, Mozart, Goethe, Brahms, Haydn, and Schubert could commit the acts of sadistic brutality that were carried out during Hitler’s abuse of power.

Our first clue to the circumstances and processes that made this possible should be searched for in the First World War and its ruinous consequences. It is easy to identify the stigma imprinted on the German people in the wake of the savagery of trench warfare on the western front and the resentment and void created by Germany’s ensuing defeat and the subsequent punishment, loss, and shame of the postwar years. The war and its aftermath as experienced by the children and youth of that time clearly shaped the nature and success of National Socialism. The young adults who became politically operative after 1929 and who filled the ranks of the SA, SS, and other paramilitary organizations such as the Hitler Youth or the League of German Girls were the children and teenagers socialized during or in the shadow of the First World War.1

National Socialism: A Young People’s Movement

The Great War was a particularly traumatic experience for younger Germans and synonymous with prolonged hunger, false or misleading war propaganda, the absence of fathers—sometimes even of both parents, as some 1.2 million German women were employed in factories or in the war industry—as well as the bankruptcy of all political values and norms.2 Among the consequences of these years of deprivation and hardships, these youths later often reacted to internal personal stress with externalized violence, and they projected all antinational and antisocial characteristics onto foreign and ethnic individuals and groups.3 This cohort also yearned for an idealized, though distant, father figure who is all-knowing and all-powerful, who expounds the merits of military valor, and who encourages his sons and daughters to honor him by proudly donning a uniform and joining the fight for the national cause.4

It has been said that the children of World War I were a fatherless generation. Over two million German soldiers never made it home, while millions more returned to their families mutilated and mentally or emotionally traumatized. The National Socialist movement’s principal adherents, and later, perpetrators, were the younger generation. The demographer and sociologist Norman Ryder states, “The Great War weakened a whole cohort in Europe to the extent that normal succession of personnel in roles, including positions of power, was disturbed. Sometimes the old remained in power too long; sometimes the young seized power too soon.”5

In the early years, the National Socialists successfully targeted German youth. An official slogan of the party stated that “National Socialism is the organized will of youth,”6 and the Party’s propagandist Gregor Strasser shouted “Step down, you old ones!” National Socialism was, in essence, a youth movement,7 and its ideology and organization matched those of the elitist principles of the German youth movement, the Wandervogel. This extremely popular group prized the virtues of a rustic life on the moors and heaths and in the forests, where the bonds of group life and group activities could develop.

The National Socialist principle of “blood and soil,” as well as the ideal and preservation of the German Volk, nation, language, and culture, appealed to the romantic notions of the postwar German youth associations. The National Socialists’ use of pageantry, flags, songs, war games, uniforms, and the “Führer Principle” struck a chord in the hearts of these lonely youths, who found purpose in comradery, group discipline, allegiance, sacrifice, and dedication to nation and leader.

Germany’s youth contributed greatly to the rapid surge in votes that the National Socialist Party gleaned from the late 1920s into the early 1930s. According to the Reich’s 1933 census, those aged eighteen to thirty represented nearly one-third of the German population. Among these, the newly enfranchised, having reached voting eligibility, actively participated in politics: in 1930 alone, there were 5.7 million new voters.8 In the elections of March 5, 1933, there were 2.5 million new voters over the previous year, and voting participation rose to 88 percent of the electorate as opposed to 75 percent in 1928.9 Another aspect of young people’s voting influence is that three million (mostly older) voters died in the period from 1928 to 1933, whereas the number of first-time voters in the same period was 6.5 million.10 It is no wonder that the National Socialist campaign specialists explicitly targeted Germany’s students.

Promises, Promises

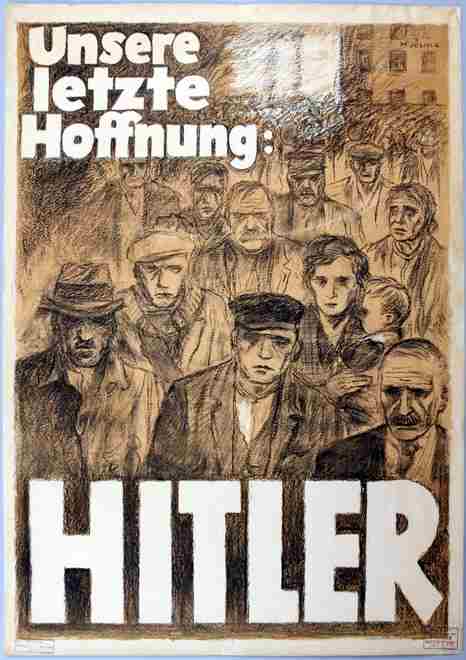

During the politically turbulent years of the republic, plagued by major economic problems and the perceived injustices of World War I and the Versailles Treaty, Hitler and the National Socialists formulated clear and promising goals. Hitler’s charismatic speeches, the relentless propaganda articles printed in the party’s paper the Völkischer Beobachter, and the prospect of strong leadership greatly boosted the National Socialists’ popularity, especially after the onset of Germany’s economic depression.

Hitler gained the support of many of the tycoons in business and industry who controlled political funds and were anxious to use them to promote a strong right-wing, antisocialist government. The financial backing Hitler received from the industrialists positioned his party on a secure financial footing and allowed him to make effective his emotional appeal to the lower middle class and the unemployed, based on the proclamation of his faith that Germany would emerge from its sufferings to resume its natural greatness.

Hitler promised a new German order to replace what he viewed as an incompetent and inefficient democratic regime. In reality, his new order was distinguished by a despotic political system based on a leadership structure in which authority flowed downward from a supreme national leader.11

Many contemporaries claimed that, during his speeches, Hitler appeared to be addressing them directly and personally. In truth, Hitler artfully responded to the wishes and goals of a wide spectrum of Germans. To the socialists, he promised that farmers would be given their land, pensions would increase, and public industries such as electricity and water would be state owned. To the nationalists, he promised that the German-speaking Volk would be united in one country, that the Versailles Treaty would be discarded, and that special restrictions would apply to foreigners. To the racially biased, he promised that Jews would be deprived of German citizenship and that immigration would be halted. To the fascists, he promised a strong central government and control of the press. To industrialists, business owners, landowners, the wealthy, and the army, he promised the remilitarization of Germany and that contracts would be awarded to Germans (“Only through the rebuilding of the military can peace be ensured,” he stated). To the workers, he promised an end to unemployment, an increase in wages, and protection from the Communist-Bolshevist threat.12

Hitler used such meetings to tell many Germans what they wanted to hear—that there was a political party that would solve all their problems. He used simplistic language and short phrases to convey his message and came across as energetic and passionate—as someone who cared about the plight of the German people. The National Socialists’ propagandists employed modern campaigning methods that included radio, mass rallies, newspapers, posters, and the novel idea of Hitler flying from city to city to deliver his allegedly mesmerizing speeches in person.

Seizing Control

Totaling four hundred thousand in 193213—four times the number of army soldiers permitted in Germany—the paramilitary SA stormtroopers came across as a strong organization that could protect Germany from its enemies, both within the nation and abroad.14 By the end of 1932, the SS counted fifty-two thousand members15 at a time when political parties depended on paramilitary formations to protect their leaders and activists at events during election campaigns.

National Socialist strategy encouraged the use of violence to intimidate or sidetrack political rivals, while allowing Hitler plausible claim that he sought election through legal means and blaming the violence on his opponents or on crisis disorders brought about by the weakness and corruption of the Weimar democracy. Although the National Socialist paramilitary and terror apparatus often provoked violence, their opposition, the Communist, Social Democratic, and German Nationalist paramilitaries, countered in kind.16

The elections of July 31, 1932, were an extraordinary triumph for Hitler. The NSDAP captured 37.3 percent of the vote, becoming the largest party in the Reichstag, though later that year, the November 6 elections proved to be a setback for the party when the vote dipped to 33.7 percent.17

Though Hitler’s popularity had slightly dropped, the National Socialists were still the largest political party. Aware of the fact that he held a strong position by virtue of his unprecedented mass following, Hitler entered into a series of intrigues with conservatives such as Franz von Papen, Otto Meissner, and President Hindenburg’s son Oskar. The threat of Communism and the rejection of the Social Democrats bound them together, and Hitler insisted that the chancellorship was the only office he would accept. Under pressure and with no other leader able to gain sufficient support to govern, President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933.18

From Democracy to Dictatorship

A few short weeks later, a fire broke out in the Reichstag (Parliament) building in Berlin, and authorities arrested a young Dutch Communist who confessed to starting it. Hitler used this episode to convince President Hindenburg to declare an emergency decree suspending many civil liberties throughout Germany, including freedom of the press, freedom of expression, and the right to hold public assemblies. The police were authorized to detain citizens without cause, and the authority usually exercised by regional governments became subject to control by Hitler’s national regime. Almost immediately, Hitler began dismantling Germany’s democratic institutions and imprisoning or murdering his chief opponents, the Communists in particular.

The final step toward Hitler’s totalitarian goal was the eradication of parliamentary democracy and the rule of law. Although the National Socialists possessed a stable working majority in the Reichstag, they sought to gain complete de facto political power by means of an amendment to the Weimar Constitution. This could be achieved through the “Act for the Removal of the Distress of the People and the Reich,” more commonly known as the Ermächtigungsgesetz or Enabling Act, by which the government of the Reich would be conferred near unlimited powers to enact laws, even in cases where legislation encroached on core bylaws of the constitution. As the Enabling Act required an amendment to the Weimar Constitution, its adoption necessitated both a two-thirds majority in parliament and the presence in the Reichstag of at least two-thirds of all its members.19

The prospects of achieving the requisite number of votes were good since the mandates of the eighty-one deputies from the Communist Party of Germany had been rescinded under the Reichstag Fire Decree. Moreover, many members of the Reichstag had already fled or been imprisoned or murdered. Hitler and his National Socialists entered into a series of negotiations with, and promises to, the remaining parties and to the representatives of the church. Only the deputies of the Social Democratic Party voted en masse against the bill, in spite of the considerable intimidation implemented by SA and SS men who surrounded the Kroll Opera House, where the parliament members were assembled.20

A mere ninety-four deputies voted against the bill while 444 voted in favor. The adoption of the Enabling Act on March 23, 1933, authorized Adolf Hitler’s government to enact laws without the consent of the Reichstag (which continued to exist), without the countersignature of the president of the Reich, and without the endorsement of the Reichsrat (Reich Council, which consisted of members appointed by the German states and participated in legislation affecting all constitutional changes).

The passing of this act marked the final collapse of the democratic state based on the rule of law and the abolition of parliamentary democracy. All legislation in the National Socialist state was now based on the Enabling Act and served to centralize public administration, the judiciary, the security apparatus, and the armed forces in accordance with the “Führer Principle”; to standardize political life in accordance with National Socialist ideology by banning political parties and mass organizations; and to obliterate freedom of the press.21

This concentration of power in the hands of the National Socialist government, and thus in the person of Adolf Hitler, completed the transition to dictatorship. When Reich President Paul von Hindenburg died the following year, Hitler claimed the titles of Führer, chancellor, and commander-in-chief of the German armed forces. The following years would be marked by masterful propaganda, the alleged “restoration of German pride,” intimidation through the terror apparatus, persecution or elimination of all opposition and minority groups, and ultimately, war and genocide.

Notes

1. Peter Loewenberg, “The Psychohistorical Origins of the Nazi Youth Cohort,” American Historical Review 76, no. 5 (December 1971): 1457–58.

2. Ibid., 1463.

3. Fritz Redl and David Wineman, The Aggressive Child (Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1957), 76–78.

4. Loewenberg, “Psychohistorical Origins,” 1458.

5. Norman B. Ryder, “The Cohort as a Concept in the Study of Social Change,” American Sociological Review 30 (1965): 848.

6. Lebendiges Museum Online, “Alltagsleben,” https://www.dhm.de/lemo/kapitel/ns-regime/alltagsleben.html.

7. Walter Z. Laqueur, Young Germany: A History of the German Youth Movement (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962), 191.

8. Loewenberg, “Psychohistorical Origins,” 1469.

9. Koppel Pinson, Modern Germany: Its History and Civilization (New York: Macmillan, 1954), 603–604.

10. Heinrich Striefler, Deutsche Wahlen in Bildern und Zahlen: Eine soziografische Studie der Reichstagswahlen der Weimarer Republik (Dusseldorf: Wende-Verlag W. Hagemann, 1946), 16.

11. National World War II Museum, “How Did Adolf Hitler Happen?,” https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/how-did-adolf-hitler-happen.

12. BBC, “Nazi Rise to Power,” https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zpknb9q/revision/1.

13. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “Adolf Hitler: 1930–1933,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, http://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/adolf-hitler-1930-1933.

14. BBC, “Nazi Rise to Power.”

15. “The SS,” History.com, https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/ss.

16. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “Adolf Hitler.”

17. Ibid.

18. “Rise to Power of Adolf Hitler,” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Adolf-Hitler/Rise-to-power.

19. Historical exhibition presented by the German Bundestag, “The Enabling Act of 23 March 1933,” Administration of the German Bundestag, Research Section WD 1, March 2006.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.