Chapter 10

The German “People’s Community”

Along with the creation of a veritable Hitler cult, National Socialism’s second most effective propaganda and integration tool was the concept of the Volksgemeinschaft (People’s Community). During the course of the First World War’s attrition warfare, people of the most varied backgrounds were forced to come together, endowing them with a true sense of a “people’s community.” Across the political spectrum from left to right, the experience of togetherness on the battlefront continued to exert its effect during the ensuing years of the Weimar Republic in the form of the Freikorps, youth movements, and völkisch (ethnic, populist, national) groups.1

The National Socialist Concept of the People’s Community

The most precise description of the National Socialist idea of the People’s Community was expressed by Hitler himself: “The social unity of German people rises above classes and status, professions and denominations and all other confusion in life, regardless of class and origin, based on blood, brought together by a thousand-year life, bound by fate, for better or worse.”2

This core component of Hitler’s Weltanschauung was repeated again and again throughout his speeches and writings.

The National Socialists’ model of Volksgemeinschaft presented a racially unified and organized hierarchy. It implied a mystical unity, a form of racial soul that united all Germans, including those living outside the existing confines of the Reich. Nonetheless, this soul was regarded as related to the land in the doctrine of “blood and soil,” within which it was affirmed that landowner and peasant lived in organic harmony.3

The historical exemplification of the German people by the National Socialists consisted of an ongoing, laborious, and ever-challenged process of becoming a Volk—a people. The earliest tribes were brought together by one leader or another, only to eventually fall apart again. The state corpus that Charlemagne had created in his Europe-wide unification process had been gradually destroyed by the strengthening of multiple dynasties and religious denominations. The unification process had once again ignited during the second German Reich from 1871 on, only to be extinguished in 1918 due to the labor unions and political parties. Hitler viewed workers’ unions as well as voters freely choosing among a democratic medley of political parties as highly dangerous forces of division that threatened the continued existence of the German people.4

Gleichschaltung: Social and Political Conformity

Within months of Hitler’s rise to power, measures were taken to counter the perceived dangers of a pluralistic democracy. Political parties were outlawed and crushed through police intervention, and labor unions and workers’ associations were disbanded. All these multiple groups and associations were replaced by large-scale National Socialist organizations, all of which were submitted and subjected to the Führerwille (Führer’s will). On a practical level, all social and political structures were now steeped in a supposedly direct Führer–Volk relationship.5 The following is a partial list of the various new organizations that served to unite the population within the vast social conformity operation and reprogramming known as Gleichschaltung.

The German Labor Front: The first of the National Socialists’ mass organizations was the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (German Labor Front), founded in May 1933, after the storm troopers’ raid on all union headquarters and the ruthless arrests of workers’ union officers. Six years later, at the outbreak of the war, the Labor Front could boast some twenty million members in Germany proper and about three million more in the other lands composing “Greater Germany.” The massive organization, with Robert Ley at its head, carried out press, propaganda, and welfare work and directed the activities of the Kraft durch Freude (Strength through Joy) program.6

The 168 unions that had been mercilessly dissolved were now constricted into one organization, which Hitler eventually said was “the only existing corporation.” Employers, manual workers, salaried employees, and urban middle-class citizens were all herded into the Labor Front without being allowed separate associations. By the end of 1934, the remodeling of the Labor Front severed the old trade union ties and loyalties and reorganized labor entirely, thus eliminating the danger of countermoves against the regime. On the one hand, the German Labor Front was independent of the Reich’s administration; on the other, it came under the complete control of the National Socialist Party. The party was eager to use the Labor Front as an instrument of its own, in order to perform any service requested by the National Socialist government.7

Robert Ley was not only the leader of the Labor Front but also held the title of chief of staff of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, a position fourth in rank in the party’s hierarchy. From there on down, the closest affiliation between the party and the Labor Front was ensured. The “privilege” of being accepted as a member of the National Socialist Party was kept to a minimum; therefore, a vast majority of the Labor Front’s members were not members of the party.

By 1939 the Labor Front counted thirty-six thousand paid officials and some two million nonpaid functionaries who offered their services in exchange for certain advantages, as well as to gain prestige. Through day-by-day conversations—and denunciations—the petty chiefs learned of workers’ attitudes, behaviors, weaknesses, loyalties, family relationships, and other characteristics. In this way, the Labor Front and the party could maintain totalitarian control.8 From 1934 on, Jews were not allowed to become members of the German Labor Front, thus excluding them from most jobs.

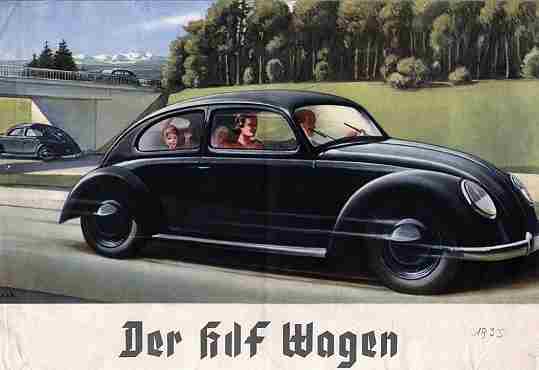

Having taken over the assets of dissolved labor unions, receiving dues from its members and contributions from the Reich’s government, the Labor Front’s financial holdings grew rapidly: by 1938 it was one of Germany’s largest banking institutions, and during the war, it extended its activities throughout the occupied lands and opened branches in all their major cities. In 1937 the Labor Front trust was extended by the creation of an automobile factory, the Volkswagenwerk (People’s Automobile Works), in which the Labor Front invested two hundred million Reichsmarks. However, the factory was soon obliged to turn out vehicles for war purposes, delaying the claims of three hundred thousand Labor Front members who had invested the two hundred million Reichsmarks in advance installment payments, in the belief that they would be entitled to the speedy acquisition of a car.9

The Reich’s Cultural Chamber: The Reichskulturkammer (Reich’s Cultural Chamber), or RKK, embodied all professions of a cultural or artistic nature, as well as culture-related businesses. Headed by the Reich’s minister of public enlightenment and propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, the RKK, with its seven departments for the various arts, obliged anyone who worked in the arts to become a member. It forced its adherents to follow the principles of National Socialism and aimed at repelling “detrimental forces.” These were considered to be the damaging influence of Jews in the cultural world, and the National Socialists employed the term entartete Kunst (degenerate art) to designate Modern and “Bolshevist” art. Jews, half-Jews, “German-blooded” citizens married to Jews, and eventually Roma and Sinti (“gypsies”) were excluded from the RKK.10 This resulted in a great number of people losing their source of livelihood.

The Reich’s Food Corporation: The Reichsnährstand, a statutory corporation of German farmers, exercised legal authority over anyone involved in agricultural production and distribution. It attempted to intercede in the market for agricultural goods, using a complex system of orders, price controls, and prohibitions and establishing its authority through regional marketing associations.11

One of the tasks set by the Reichsnährstand was that of implementing the Blut-und-Boden (blood and soil) ideology. This aimed at preserving the “peasantry as the blood source of the people” and, through this, permanently ensuring the nourishment of the people. In order to achieve this, the Reichsnährstand was to promote the creation of a “new peasantry” and to counter migration into the cities.12

Under the legislation of the Reichsnährstandsgesetz (law), farmers were bound to their land as most agricultural land could not be sold.13 The law was enacted to protect and preserve Germany’s smaller hereditary estates that were no larger than 125 hectares (308 acres). Below that acreage, farmlands could “not be sold, divided, mortgaged or foreclosed upon.”14 Cartel-like marketing boards fixed prices, regulated supplies, and oversaw almost every facet of directing agricultural production on farmlands. For instance, in addition to deciding what seeds and fertilizers were to be applied to farmland, the Reichsnährstand countered the sale of foreign food imports within Germany and monitored the payment of debts.15

As the scope and depth of the National Socialists’ command economy escalated, food production and the rural standard of living declined. By autumn 1936, Germany began to experience critical shortages of food and consumer goods, despite spending billions of Reichsmarks on subsidies to farmers.16 Germans were even subjected to the rationing of many major consumer goods, including produce, butter, and other consumables.17 Beside food shortages, Germany began to encounter a loss of farm laborers, whereby up to 440,000 farmers had abandoned agriculture between 1933 and 1939.18

The Reichsnährstand’s argument that Germany “needed” an additional seven to eight million hectares (17.3–19.8 million acres) of farmland, and that consolidation of existing farms would displace many existing farmers who would need to work new land, influenced Hitler’s decision to invade the Soviet Union.19

The Kraft durch Freude Program: The National Socialist group called Kraft durch Freude or KdF (strength through joy), a suborganization of the German Labor Front, was created to promote the “enjoyment of life and work.” Its goals also included the promotion of good health, efficiency, and team spirit in an effort to increase the nation’s performance potential and, with it, economic productivity. The KdF’s activities were directed at improving the work environment and providing leisure and cultural programs to workers. It was meant to bridge the class divide by allowing the “little man” access to leisure activities such as theater tickets and vacation trips—formerly reserved for the middle and upper classes.20 Flaunting the advantages of National Socialism to the people, the KdF became the world’s largest tourism operator.21

Large ships, such as the Wilhelm Gustloff, were built specially for KdF cruises. Workers and their families were also rewarded by being taken to the movies, to parks, to fitness clubs, on hikes, to sports activities, and out for concerts. Borrowing from the Italian fascist organization Dopolavoro (After Work) but extending its influence into the workplace as well, KdF rapidly developed a wide range of activities and quickly grew into one of Germany’s largest organizations. According to official statistics, 2.3 million people took KdF holidays in 1934. By 1938, this figure rose to 10.3 million.22

Among the KdF projects, the largest was undoubtedly Prora, also known as the Colossus of Prora, a building complex on the island of Rügen on a lagoon near the Baltic Sea. Built between 1936 and 1939 as a beach resort for as many as twenty thousand holidaymakers, the propaganda jingle here was that, thanks to the National Socialists, the working class could now afford a beach holiday. It consisted of eight identical buildings along a stretch of 4.5 kilometers (2.8 mi), parallel to the beach, with the surviving structures stretching about three kilometes (1.9 mi) today. The project was neither completed nor ever used as a holiday resort.

At the outbreak of war, holiday travel ceased. Until then, KdF had sold more than forty-five million package tours and excursions.23 By 1939, it had over seven thousand paid employees and 135,000 voluntary workers, organized into divisions covering such areas as sport, education, and tourism. The KdF also designated one or more wardens in every factory and workshop employing more than twenty people.

In the 1930s, the Kraft-durch-Freude program was generally regarded as an exemplary endeavor for the good of the people and as an incentive for a more productive workplace. It drew recognition even on an international level when it was awarded the 1939 Olympic Cup by the International Olympic Committee.24 It should be noted, however, that KdF was available neither to Jews nor Sinti or Roma, once again stressing the National Socialists’ divide between the German Volk and the rassenfremd (racially foreign) members of society.

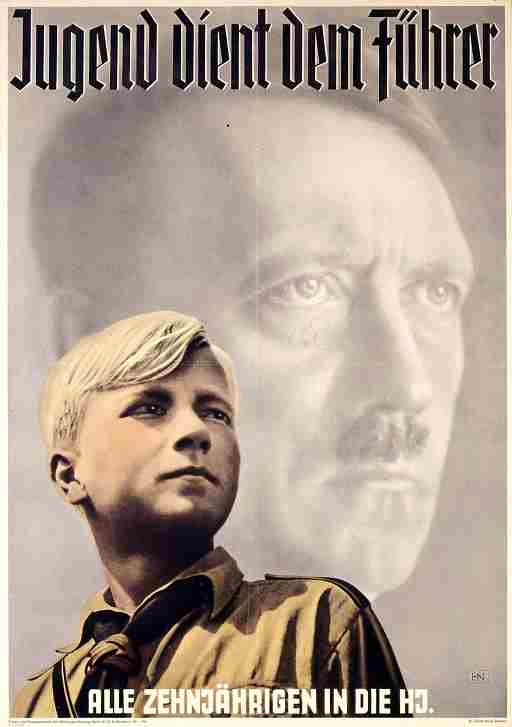

The Boys and Girls of the Hitler Youth: With the intention of shaping future German adults, the National Socialist regime set about indoctrinating its most influenceable subjects: children and teenagers. In 1938 Hitler stated,

These boys and girls enter our organizations [at] ten years of age, and often for the first time get a little fresh air; after four years of the “Young Folk” they go on to the Hitler Youth, where we have them for another four years. . . . And even if they are still not complete National Socialists, they go to Labor Service and are smoothed out there for another six, seven months. . . . And whatever class consciousness or social status might still be left . . . the Wehrmacht will take care of that. And when they then return after two, three or four years, so that they do not—under any circumstances—slide backwards, we immediately take them into the SA, SS, etc. And they will no longer be free their entire lives. And they are content with that.25

The party’s ideology and organization coincided with the elitist and antidemocratic elements of the German youth movement, a collective term for a cultural and educational organization that started in 1896. The German scouts and the Wandervogel (literally “migratory bird,” a designation for members of the German and Austrian youth movements), while essentially nonpolitical, retreated to the rustic life on the moors, heaths, and forests, where they cultivated the bonds of group life. The National Socialists’ emphasis on “blood and soil,” of Volk, nation, language, and culture, appealed to the nature of the German youth associations. The Hitler Youth took over many of the symbols and a good part of the elements that characterized the already existing German youth movement.26 According to Walter Laqueur, the historian of the Hitler Youth movement, “National Socialism came to power as the Party of youth.”

At the time of Hitler’s campaigning, a large percentage of Germany’s impressionable younger generation had suffered the massive health, nutritional, and material deprivation, as well as parental absence, of Central Europe during World War I and in the postwar years. This undoubtedly led to long-term effects on the personalities of these young people. Their weakened character structure likely manifested in aggression as well as in defense mechanisms like projection and displacement. The fact that inner rage could easily be mobilized by a renewed anxiety-induced trauma in adulthood is validated in the subsequent political conduct of this cohort in Germany’s Great Depression (1929–1933), when they joined extremist paramilitary and youth organizations as well as radically motivated political parties.

The National Socialist Party already began targeting German youth in the 1920s as a receptive audience for its propaganda messages. It emphasized that the party was a movement of youth: motivated, resilient, forward looking, and full of hope. Millions of young Germans were won over to National Socialism not only in the classroom but thanks to extracurricular activities. In January 1933, the Hitler Youth counted approximately one hundred thousand members, but by the end of the year this figure had increased to over two million. By 1937 membership in the Hitler Youth increased to 5.4 million before becoming mandatory in 1939. The Third Reich then prohibited or dissolved competing youth organizations.27

The only organization that bore Hitler’s name, the Hitler-Jugend (Hitler Youth), consisted of several subgroups: the Deutsches Jungvolk, boys ten to fourteen years old; the Hitler-Jugend, boys fourteen to eighteen; the Jungmädel, girls ten to fourteen; and the Bund Deutscher Mädel, girls fourteen to eighteen.

Though up until 1939 membership was not mandatory, not joining the organization was, nevertheless, frowned upon. From 1939 on, membership became compulsory and, for boys, often led to enlistment into paramilitary organizations: Hitler Youth were deployed in the navy, in aviation, for motor vehicles, and in the news. In addition, some twenty thousand volunteers came to form the fanatical SS Hitler-Jugend Armored Division.28

The Hitler Youth oath followed the principles of the Volk–Führer idealization and indoctrination: “In the presence of this blood banner which represents our Führer, I swear to devote all my energies and my strength to the savior of our country, Adolf Hitler. I am willing and ready to give up my life for him, so help me God.” This sense of allegiance, obedience, and honor shaped the mind-set of many a future soldier or member of the SS on the battlefields of World War II.

Welfare Organizations of the People’s Community: Founded in 1932, the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt (National Socialist People’s Welfare) rapidly grew into the world’s largest welfare organization with about eleven million members in 1938. The NSV, as it was referred to, disbanded most of the preexisting welfare groups, and those that it allowed to subsist, such as Caritas and the Red Cross, were closely monitored by the leading organization. Consistent with National Socialist ideology, the NSV was not a charitable movement in the sense that is familiar to us but rather sought to help others help themselves so that they could become “useful and motivated” members of the People’s Community. “Hopeless” or “wretched” cases were handed over to the official departments or to other welfare organizations. The NSV saw as its mission to strengthen the People’s Community through the communal spirit and a sense of solidarity: “All for one and one for all.”29

The Hilfswerk Mutter und Kind (Mother and Child Aid Organization) was founded by the NSV in 1934 with the aim of supporting families and mothers who were racially pure and to encourage the latter to bear numerous children. The mother and child aid group’s assistance included care services from the NS nursing organization, economic benefits and financial aid, help with finding a job, health promotion, rest homes for mothers, child nourishment, and the providing of kindergarten and childcare positions. Most of the Mother and Child Aid Organization’s workers were volunteers: by 1939 they were half a million strong.30

The Compulsory Reich Labor Service: Known also as the RAD, the Reichsarbeitsdienst (Reich Labor Service) was formed in 1934 as the official National Socialist Party’s work service. During Germany’s depression in the late 1920s, a number of political, church, and civic groups organized work camps to help provide some employment for the numerous ex-servicemen and the staggering numbers of unemployed workers. Generally, these work camps supplied labor for various community and agricultural construction services throughout Germany and, in a general manner, helped relieve the strain of high unemployment. Even in the National Socialist Party’s early years, the RAD also created a number of such camps.31

Service in the Reichsarbeitsdienst eventually became compulsory for all males between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five. They would first join the labor service for a period of six months before joining one of the branches of the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) for two more years. The RAD was not, however, a part of the German armed forces but an independent state organization and an auxiliary to the Wehrmacht.32

The RAD was not limited to men but also had many women serving in the organization. The “frontline” rank-and-file members who made up the bulk of the RAD workforce were armed with spades and used bicycles as their means of transport. Prior to World War II, the RAD participated in work projects such as the reclamation of marshland for cultivation, the building of dams, and the construction of roads.

The RAD also assisted the German armed forces during the occupation of Austria, the occupation of the Sudetenland, and the occupation of Czechoslovakia. During the summer of 1938 and up until the outbreak of World War II, some three hundred Abteilungen or units (a unit comprised between two and three hundred members) of the RAD participated in the construction of the massive Siegfried Line fortification along Germany’s border with France. In the east, another oune hundred RAD units were enrolled in the construction of the Ostwall fortification line along Germany’s border with Poland. As war drew nearer, in August 1939 some 115 RAD units served in East Prussia, helping with harvest work, while other RAD units served in Danzig.33

At the outbreak of World War II, the Reichsarbeitsdienst comprised about three hundred thousand members.34 Some 1,050 individual units were put at the disposal of the Wehrmacht to build roads, clear obstacles, dig trenches, build airstrips, lay minefields, erect fortifications, deliver food and ammunition to the troops, and carry out any necessary support services. Serving throughout the military theater, RAD units were often encircled and forced into frontline combat, while other units were drafted directly into military service on the spot. In 1942, there were at least 427 RAD units serving on the Eastern Front. During the war years, the RAD pursued its mission of training young men prior to their service in the Wehrmacht by providing construction and agricultural work for the Reich.35

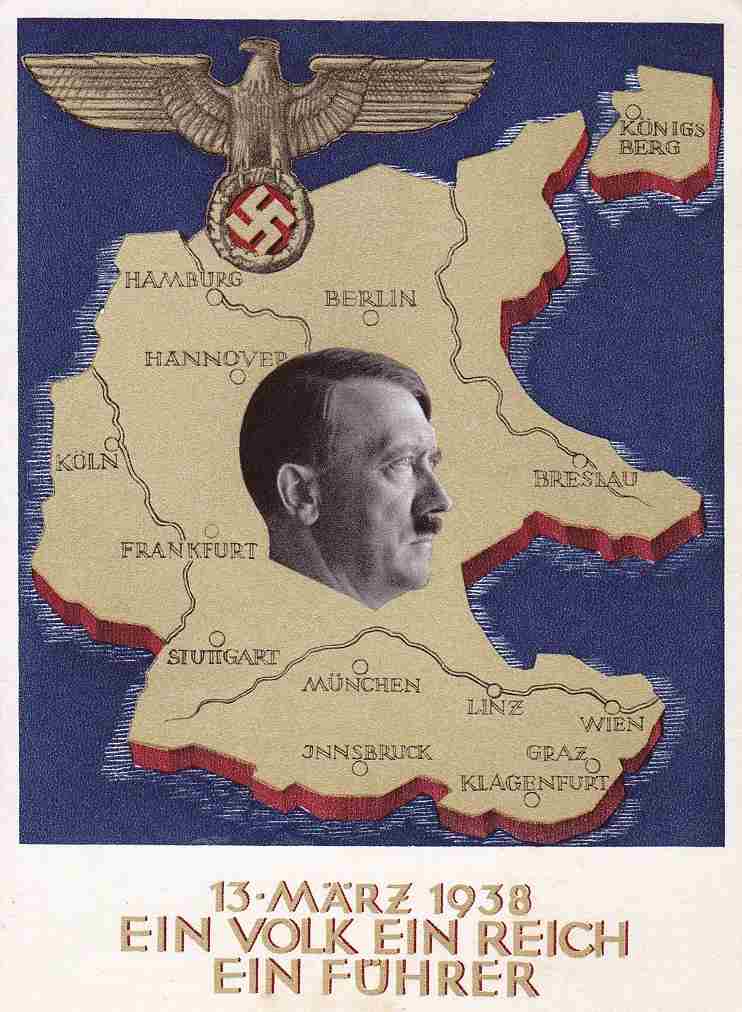

Ein Volk, Ein Reich, Ein Führer

Following extreme racist and authoritarian principles, the National Socialists removed individual freedoms and, in favor of the people’s community, established a society that would, in theory, transcend class and religious differences. The Führer’s will became the foundation for all legislation: the Führerprinzip (Führer principle) dictated all facets of German life.

According to this principle, authority flowed downward from Hitler and was to be obeyed unquestioningly. All “racially pure” Germans, designated as Volksgenossen (people’s comrades), were expected to aid those who were less fortunate and to sacrifice time, wages, and even their lives for the common good. In theory, neither lowly birth nor modest economic circumstances would be hindrances to social, military, or political advancement. NS propaganda played a decisive role in selling the myth of the People’s Community to Germans, who yearned for unity, national pride, and greatness, as well as for a break with the rigid social stratification of the past. In this way, propaganda helped prepare the German public for a future defined by National Socialist ideology.

The National Socialists’ emphasis on the importance of the Volk, the people, awakened an emotional response from a large percentage of the population. Terms such as Volkswagen (people’s automobile), Volkskanzler (people’s chancellor), Volksempfänger (people’s radio), Volkskühlschrank (people’s refrigerator), Volkssturm (people’s army), and even Volksgasmaske (people’s gas mask) were commonly used in everyday language.

From a historical viewpoint, the Third Reich experienced a period of solidified power during which the idea of the People’s Community appealed to a large portion of the population. The economic improvement and the modest increase in consumer options represented important factors, but more significant was the change in the general mood. The purpose of Gleichschaltung was to eliminate any form of opposition or dissent and establish a totalitarian state, in which the NS Party wielded complete control over every facet of society.

The use of associations and social organizations as instruments for educating the masses was highly effective, as evidenced by the fact that a significant proportion of adult Germans were affiliated with several of these organizations. The majority of Germans believed in the revival of the nation, their own upward mobility, and a brighter future for themselves and future generations. Nonetheless, the propagandists knew that constant encouragement and reprogramming was necessary in order to keep the cogs of the People’s Community oiled and turning.36

It did not take long for a large majority of Germans to believe that they were, indeed, superior to others and that the directives given by the Führer should be followed to the letter. Hitler’s mesmerizing indoctrination of the German Volk—along with the threatening elements of the terror apparatus within what had soon become a police state—resulted in a vast number of citizens adopting the new “Holy Trinity” doctrine of Ein Volk, Ein Reich, Ein Führer: One People, One Empire, One Leader. A united Volk was, indeed, emerging, at the cost of those who were deemed unfit to join its ranks.

Notes

1. Volker Dahm, “Die ‘Deutsche Volksgemeinschaft’ und ihre Organisationen,” in Die Tödliche Utopie, ed. Volker Dahm et al. (Berlin: Verl. Dokumentation Obersalzberg im Institut für Zeitgeschichte, 2008), 213.

2. Max Domarus, ed., Hitler: Speeches and Proclamations, vol. 3, The Years 1939 to 1940 (Würzburg: Domarus, 1997), speech on Heldengedenktag (Heroes’ Memorial Day) 1940, p. 1497.

3. Robert Cecil, The Myth of the Master Race: Alfred Rosenberg and Nazi Ideology (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1972), 166.

4. Dahm, “Die ‘Deutsche Volksgemeinschaft,’” 214.

5. Ibid., 253.

6. Ernest Hamburger, “The German Labor Front,” Monthly Labor Review 59, no. 5 (November 1944): 932.

7. Ibid., 933.

8. Ibid., 934.

9. Ibid., 935.

10. Dahm, “Die ‘Deutsche Volksgemeinschaft,’” 262–64.

11. Frieda Wunderlich, “Germany’s Defense Economy and the Decay of Capitalism,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 52, no. 3 (May 1938): 401–30.

12. Dahm, “Die ‘Deutsche Volksgemeinschaft,’” 265.

13. Raffael Scheck, Germany, 1871–1945: A Concise History (Oxford: Berg, 2008), 167.

14. Adam Young, “Nazism Is Socialism,” Free Market, Mises Institute, September 1, 2001, https://mises.org/library/nazism-socialism.

15. Sheri Berman, The Primacy of Politics: Social Democracy and the Making of Europe’s Twentieth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 146.

16. Aly Götz, Hitler’s Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State (New York: Metropolitan, 2007), 55.

17. Evans, Third Reich in Power, 411.

18. Martin Kitchen, A History of Modern Germany, 1800–2000 (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006), 287.

19. “Food and Warfare: Marching on Their Stomachs,” Economist, February 3, 2011.

20. Dahm, “Die ‘Deutsche Volksgemeinschaft,’” 269.

21. “Wellness unterm Hakenkreuz,” Spiegel Online, July 19, 2007, https://www.spiegel.de/geschichte/nazi-propaganda-wellness-unterm-hakenkreuz-a-948936.html.

22. T. W. Mason, Social Policy in the Third Reich: The Working Class and the National Community (Providence, RI: Berg, 1993), 160.

23. Hasso Spode, “Some Quantitative Aspects of ‘Kraft durch Freude’ Tourism,” in Europaikos tourismos kai politismos, ed. Margerita Dritsas (Athens: Livanis, 2007), 125.

24. “The Olympic Cup,” Olympic-Museum.de, https://web.archive.org/web/20060623145224/http://www.olympic-museum.de/awards/olympic_cup.htm.

25. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “Indoctrinating Youth,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/indoctrinating-youth.

26. Loewenberg, “Psychohistorical Origins of the Nazi Youth Cohort,” 1470.

27. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “Hitler Youth,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/hitler-youth-2.

28. Dahm, “Die ‘Deutsche Volksgemeinschaft,’” 273–75.

29. Ibid., 269.

30. Ibid., 271.

31. Feldgrau, “The German Reichsarbeitsdienst (Reich Labor Service),” https://www.feldgrau.com/WW2-German-National-Work-Service-Reichsarbeitsdienst/.

32. Ibid.

33. Ibid.

34. Dahm, “Die ‘Deutsche Volksgemeinschaft,’” 277.

35. Feldgrau, “German Reichsarbeitsdienst.”

36. Norbert Frei, permanent exhibit, Topography of Terror Documentation Centre, Berlin, December 7, 2022.