Chapter 17

One Crown for Two Empires

Hitler and the First Reich

The National Socialists’ widespread use of propaganda to gain approval and ensure compliance is familiar to us. Few are those, however, who realize that the terminology “Third Reich” as well as “Thousand-Year Reich” were effective elements of Hitler’s bid for recognition as the builder of an empire, rather than merely the promoter of a political agenda.

The Roman Empire

The early Roman emperors saw it their duty to the gods to assume responsibility for the respect and propagation of pagan religion. However, beginning with the conversion to Christianity of Roman Emperor Constantine I, who ruled from 306 to 337, the majority of Roman emperors who followed both defended and expanded the Christian faith. To this effect, each emperor’s role was to enforce doctrine, root out heresy, and uphold ecclesiastical unity.

After the death of Julius Nepos in 480 and the fall of the Roman Empire, the title “emperor” became defunct in Western Europe, which led the barbarian kingdoms to acknowledge the authority of the eastern emperor, at least nominally. Both the title and the relationship between the emperor and the church persevered in the Eastern Roman Empire throughout the medieval period, and the ecumenical councils of the fifth to eighth centuries were convened by the eastern Roman emperors.1

In 797, the Eastern emperor, Constantine VI, was deposed and replaced by his mother, Irene. The papacy, which up until this point had continued to recognize the rulers in Constantinople as Roman emperors, regarded the imperial throne as vacant since, in their opinion, a woman could not rule the empire.2

Charlemagne’s Legacy

For this reason, Charlemagne was crowned emperor of the Romans (Imperator Romanorum) by Pope Leo III as the successor of Constantine VI. Thus began the long history of the Holy Roman Empire on Christmas Day of the year 800, a symbolic and convenient date to be remembered throughout the centuries to come. The new empire was named after the defunct Roman Empire in a medieval notion of translatio imperii (transfer of rule), which invests supreme power in a single ruler. The act was also considered a renovatio Romanorum imperii (renewal of the Roman Empire), a revival of the Western Roman Empire.

By the time Charlemagne received this great honor, he had become king of the Franks and the Lombards and conquered vast parts of Western and Central Europe as well as Northern Italy. By the power of the sword, Charlemagne, also known as emperor of the west, united a number of peoples within his vast empire—notably, the Saxons and Bavarians—but at the same time he rooted out paganism throughout his territories. He also expanded a reform program of the church that helped to strengthen its power, advance the skills and moral quality of the clergy, standardize liturgical practices, and improve the basic tenets of faith and morals.

Disappointingly, Charlemagne’s three grandsons split his Europe-wide “Carolingian” empire into three realm that came to be known as West, Middle, and East Francia (Francia = land of the Franks). East Francia was first ruled by a member of Charlemagne’s bloodline, but eventually, the lords of East Francia—namely, Saxon, Franconian, Bavarian, and Swabian nobles—no longer followed the tradition of electing someone from the Carolingian dynasty as a king to rule over them: on November 10, 911, they elected one of their own as the new king.

Among this early line of German rulers, a certain Otto won a decisive victory over the Magyars in the Battle of Lechfeld, and in 951 he came to the aid of Adelaide, the widowed queen of Italy, defeating her enemies. He then married her and, by so doing, took control of Italy. As a result, Otto I was crowned German-Roman Emperor by the pope in 962, and from then on, the affairs of the German kingdom became closely intertwined with those of Italy and the papacy. Otto’s coronation as emperor resulted in designating German kings as successors to the former empire of Charlemagne and is considered the official beginning of the First German Reich.

The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation

The term sacrum (i.e., “holy” in the sense of “consecrated”), in connection with the medieval Roman Empire, was used from 1157 on, during the reign of Frederick I “Barbarossa.” The term was added to reflect Frederick’s ambition to dominate Italy and the papacy. Later, in a decree following the 1512 Diet of Cologne, the name was officially changed to Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (in German, Heiliges Römisches Reich Deutscher Nation).

In the last centuries of the Holy Roman Empire, its territories resembled a piecemeal union of territories, with the Kingdom of Germany at its center and surrounded by its other components, such as the Kingdom of Italy and the Kingdom of Burgundy. For much of its history, the Holy Roman Empire consisted of a vast patchwork of hundreds of entities of varying sizes that included principalities, duchies, counties, free imperial cities, and other domains.

The territories administrated by the Holy Roman Empire in terms of present-day nations included Germany (except Southern Schleswig), Austria (except Burgenland), the Czech Republic, Switzerland and Liechtenstein, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Slovenia (except Prekmurje), along with vast parts of eastern France (mainly Artois, Alsace, Franche-Comté, French Flanders, Savoy, and Lorraine), northern Italy (principally Lombardy, Piedmont, Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Trentino, and South Tyrol), and western Poland (predominantly Silesia, Pomerania, and Neumark).

By the Golden Bull edict of 1356, the Holy Roman Empire’s electoral council was set at seven “princes” (three archbishops and four secular princes). This electoral system remained unchanged until 1648, when the settlement of the Thirty Years’ War required the addition of a new elector to maintain the precarious balance between Protestant and Catholic factions in the empire. Yet another elector was added in 1690, and the entire college was reshuffled in 1803, a mere three years before the empire’s dissolution.

Wandering Emperors

A prospective emperor had first to be elected “King of the Romans.” Following this selection, the king could theoretically claim the title of emperor only after being crowned by the pope. In many cases, this took several years as the king was often held up by other tasks: frequently, he first had to resolve conflicts in rebellious northern Italy, or found himself in a quarrel with the pope himself. Later emperors dispensed with the papal coronation altogether, being content with the styling “emperor-elect”; in fact, the last emperor to be crowned by a pope was Charles V in 1530.

The Holy Roman Emperors possessed no permanent capital city, and they traveled from town to town to administrate their far-reaching territories. In the late Middle Ages, Nuremberg ranked as the “most distinguished, best located city of the realm,” and the town was thus chosen as the site of numerous imperial diets (meetings of the deliberative body of the Holy Roman Empire). In 1356 Emperor Charles IV designated Nuremberg as the town where every newly elected emperor was obliged to summon his first imperial diet. In this way, Nuremberg became one of the main centers of the empire, in addition to Frankfurt, where the kings were elected, and Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle), where they were crowned.

Most of the emperors paid numerous visits to Nuremberg: Ludwig IV “the Bavarian” resided there seventy-four times and Charles IV fifty-two times. In 1423, Sigismund gave the very precious Imperial Regalia into the keeping of the city, a mark of exceptional trust. The Habsburgs Friedrich III and his son Maximilian I were the last emperors to reside for longer periods in the castle and city.

Their successor Charles V broke with the tradition of emperors holding their first imperial diet in Nuremberg. Because of epidemics raging in Nuremberg, he relocated his first imperial diet to Worms and did not visit Nuremberg until 1541, on his way to the Regensburg Diet. Nuremberg’s acceptance of the Reformation in 1524 alienated the Protestant city from the Catholic emperors, and in 1663, after the Thirty Years’ War, the imperial diet was relocated permanently to Regensburg.

Following Charlemagne’s successors’ rule (the Carolingian line), other ruling houses acquired the position, such as the Ottonians, Saliens, Hohenstaufens, the House of Luxembourg, the Bavarian Wittelsbachs, and the Austrian Habsburgs or the House of Habsburg-Lorraine. After 1438, the emperors were sourced solely from the house of Habsburg and Habsburg-Lorraine, with the brief exception of Charles VII, who was a Wittelsbach.

The gradual end of the Holy Roman Empire approached in several stages. The medieval idea of unifying all Christendom into a single political entity, of which the church and the empire were the leading institutions, began to lose its luster. The Swiss Confederation, which had already established near independence in 1499, as well as the Northern Netherlands, left the empire. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which ended the Thirty Years’ War, gave the territories almost complete sovereignty. Eventually, the Holy Roman Empire weakened into a powerless entity, existing in name only.

The Habsburg emperors instead focused on consolidating their own estates in Austria and elsewhere. Throughout the eighteenth century, the Habsburgs became embroiled in various European conflicts, such as the War of the Spanish Succession, the War of the Polish Succession, and the War of the Austrian Succession. Consequently, German dualism between Austria and Prussia dominated the empire’s history after 1740.

The Holy Roman Empire formally went into dormancy on August 6, 1806, when the Holy Roman Emperor Francis II (from 1804, Emperor Francis I of Austria) abdicated following his military defeat by the French under Napoleon. Symbolically, the Holy Roman Empire was born with the crowning of Charlemagne as emperor of the Romans in the year 800 and expired one thousand years later in 1806. Hitler exploited the long-lived history of the Holy Roman Empire—the First Reich—as a propaganda catchphrase, not only claiming tenure of the “Third Reich” but touting another “Thousand-Year Reich” of Germanic power and glory.

For clarity’s sake, the “Second Reich” was the German Empire or the Imperial State of Germany that existed from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the abdication of Emperor Wilhelm II in 1918 at the close of World War I.

The Priceless Imperial Regalia: The Right to Rule

The Imperial Regalia and imperial relics are of various origins and date from the eighth to the fourteenth centuries. They consisted of twenty-eight objects that were safeguarded in Nuremberg for 350 years, plus three items kept in Aachen, the city of the emperors’ coronation. Components of this secular treasure, as well as religious relics, were used as props during the crowning of the Holy Roman Emperor and as a symbolic affirmation of both his worldly and “holy” authority. Until the fifteenth century, the Imperial Regalia enjoyed no firm depository and sometimes accompanied the emperor on his journeys through the empire. As conflicts often arose regarding the legitimacy of the rule, it was essential for the emperor to physically possess the regalia. Some repositories, such as imperial castles or well-guarded towns of reliable governance, were used on occasion until Emperor Sigismund honored Nuremberg by permanently entrusting the city with the imperial treasure.

The most significant symbols of worldly power were the tenth-century octagonal crown (supposedly commissioned by Otto I), the scepter, the orb, the imperial sword, and the so-called Sabre of Charlemagne. The most precious religious relic was undoubtedly the Holy Lance, allegedly the spear that the Roman soldier Longinus thrust into Jesus’s side while he agonized on the cross. Other holy relics included St. Stephen’s purse, a piece of the Crucifixion cross, a fragment of Jesus’s manger, a scrap of the tablecloth of the Last Supper, and other artefacts associated with saints in Jesus’s time and later. The third part of the Imperial Regalia consisted of the coronation robe and other richly decorated vestments worn during the emperor’s coronation.

In medieval times, royal authority was closely associated with the concept of divine justification, Gottesgnadentum, the divine right of kings, or, so to speak, the right to rule by the grace of God. In this manner, the Imperial Regalia stood for the connection between secular and divine authority but, at the same time, represented an embodiment of that authority. The regalia guaranteed royal power greater than the emperor himself—even more than his blood and dynasty.3 The medieval crown treasures in this collection are the only ones that have survived nearly unscathed over the centuries, thus lending them tremendous historical value and making them one of the most precious treasure collections in existence.

Symbols of Divine Power

The imperial crown’s unusual octagonal form mimics the characteristic shape of Aachen cathedral, Charlemagne’s resting place, where between 936 and 1531 many German kings and queens were crowned, among them Holy Roman Emperors. This element contributes to making this crown so unique as, according to Christian numeric symbolism, the number eight stands for the concept of salvation, the process of humankind’s redemption through the Christian God. The crown’s very shape, therefore, is a reminder of its sacred connotations.4 Historic baptistries, principally in Italy, are eight sided, clearly a symbol of salvation through the act of baptism.

The stone plates forming the sides of the crown follow a strict numerical pattern. The number of stones at the front and the rear of the crown each equal twelve. In all, the sides contain 120 precious stones and 240 pearls, both of which are multiples of twelve. In the Christian tradition, twelve is a sacred number as it stands for the twelve tribes of Israel and, naturally, for the twelve apostles. As a consequence, the number twelve also stands for the propagation of faith and the Christian church itself.5

Of the four enameled plates, three bear the images of Old Testament figureheads: King Solomon, King David, and King Hezekiah with the prophet Isaiah, thus lending the object even more symbolic weight through the additional context of the ancient world. Inscriptions held by these kings of old explain their connection with the king who bears this crown: they refer to God’s grace, righteousness, wisdom, and long life.6 It is safe to assume that this crown was unmistakably to be viewed not only as a secular symbol of power but as a holy artifact as well.

The symbol of the imperial orb follows a tradition that dates back to antiquity: the ball represents the earth and thus world domination. The cross atop the globe represents Christ as ruler of the cosmos—the emperor is his representative. The scepter has long been considered a symbol of earthly power among rulers, but in Greek antiquity, it was viewed more like a staff—a (shepherd’s) staff is also a symbol of leadership.

The Holy Lance spearhead is inlaid with a long nail, allegedly one of the nails from Jesus Christ’s cross. It was thought that this “lance of Longinus,” supposedly used during the Crucifixion, was presented to Charlemagne by Pope Hadrian I. A golden cuff hides a break in the spear’s blade and is inscribed with the words “Lance and Nail of the Lord.” As the foremost of the imperial insignia, it ranked above the crown. The power of invincibility was ascribed to it, which was thought to have given Emperor Otto I his victory over the Hungarians and the Slavs.7

Another major component of the Imperial Regalia is the so-called Coronation Evangeliar, produced at Charlemagne’s court in Aachen in 794. At his coronation, the new “king of the west,” Charlemagne, swore the oath on this Gospel—his fingers touching the first pages of this book. This act alone lent both historic and symbolic value to this beautifully gold-bound Gospel manuscript, some of which was written in real gold.8

A Coveted Treasure

During his eastward advance, Napoleon, one of history’s greatest plunderers, was eager to secure the Holy Roman Empire’s Imperial Regalia. When, in 1796, Napoleon’s French troops crossed the Rhine, Nuremberg’s Imperial Regalia was hurriedly relocated farther east in Regensburg and then expedited on to Vienna in 1800. Similarly, the three objects comprising the Imperial Regalia in Aachen were sent to Paderborn in 1794 and reunited with the remainder of the treasure in Vienna in 1801. The transferal to Vienna was entrusted to Regensburg’s imperial envoy, Baron von Hugel, who promised to return the treasure to Nuremberg and Aachen, respectively, once the danger was over. After peace was restored, however, von Hugel took advantage of the confusion regarding the Imperial Regalia’s rightful ownership and sold the entire collection to the Habsburg family.9 Furious, both the city of Nuremberg and the town of Aachen demanded that the treasures be returned—all to no avail.

During the Second German Reich (1871–1918) or Kaiserreich, the Hohenzollern family, beginning with Emperor Wilhelm I, strove to lend the new empire historic weight as a linear succession to the “old empire.” This Wiederauferstehung des Reiches (resurrection of the empire) was also symbolized in the depiction of the Holy Roman Empire’s slightly modified crown incorporated in the coat of arms of the Second German Empire. A good example of the crown’s use as a symbol is at the Niederwalddenkmal near Rüdesheim overlooking the Rhine River. The impressively large monument was erected by Bismarck to commemorate Germany’s unification in 1871 as well as its victory in the Franco-Prussian war. It depicts an allegoric representation of Germany—a gigantic female Germania figure—clutching the unique and historic crown.10

The Third Reich’s “Little Treasure Chest”

With its medieval history as an imperial city of the Holy Roman Emperors, as well as home to numerous German artists such as Albrecht Dürer, Nuremberg was promoted by Adolf Hitler and National Socialist authorities as “the most German of German cities.” For propaganda purposes, they also endeavored to showcase the Führer as the true keeper and heroic reformer of the ancient Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. No sooner had Hitler annexed Austria in March 1938 than the Imperial Regalia was repatriated from its Viennese stronghold back to Nuremberg.

The transfer by armored train was carried out with much fanfare and theatrics as further proof of Hitler’s promise to right the wrongs that Germany had suffered in its past. It is interesting to note that Austria did not agree to transfer or “return” the Imperial Regalia to Nuremberg but, instead, to hand the treasure over to Hitler, who in turn handed these historic objects over to the city of Nuremberg.11 This detail confirms that, in the same way that Charlemagne attempted to emulate Julius Caesar when he was crowned Roman emperor in 800, Hitler sought to align himself in the tradition of outstanding historical figures such as Charlemagne and Otto I. More importantly, Hitler was seeking to inject the Third Reich with “historical” value, thanks to the restoration to Germany of the most important symbols of power of the First German Reich.12

It is not by chance that, as early as 1927, Hitler chose Nuremberg as the backdrop for the National Socialist party rallies. Following the “homecoming” of Nuremberg’s Imperial Regalia in 1938, National Socialist propaganda monikered it “Germany’s Little Treasure Chest.” A solemn ceremony was staged at Nuremberg’s Gothic St. Katherine’s Church—the new repository of the Imperial Regalia—during which the treasure was “handed over” by Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the National Socialist governor of the German Ostmark (Austria’s new designation).

In his speech, Austria’s governor declared,

Austria has returned, the Reich has been founded anew. In these festive hours the Führer in his role as unifier of the Reich, has recovered the crown and royal treasures of the Holy Roman Empire from the palace in Vienna, to be placed under the protection of Greater Germany. Today I carry out the wishes of the Führer, who orders the return of the insignia, which are sacred to the German people and represent German imperial dignity, coming back to the city at the heart of the empire.

In no other German city is there as strong a connection between past and present of the Great German Reich with such symbolic unity and expression as in Nuremberg, the old and new imperial city. This city, which the old German Reich deemed fit to defend the Regalia behind its walls, has regained ownership of these symbols which testify to the power and strength of the old Reich. Today Nuremberg is the city of the Party Rallies, the manifestation of German power and greatness in a new German Reich.

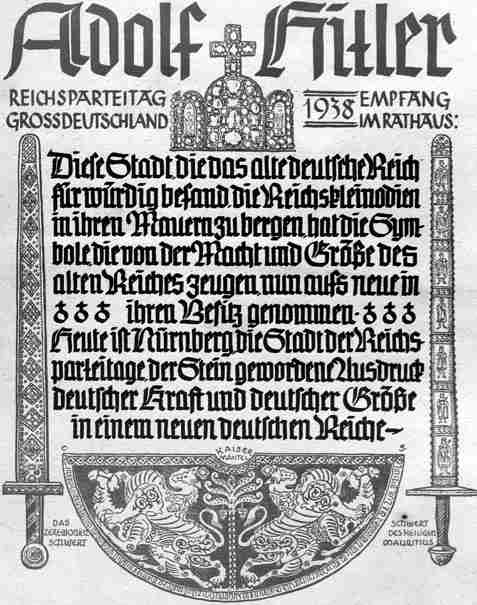

As the event coincided with the party rallies, the return of the regalia was exploited as that year’s rally theme. The party rally’s brochure featured drawings of the crown, coronation robe, and two swords of the Imperial Regalia, as well as a text suggestive of the association of the old and the new Reich.13

A few months into World War II, the Imperial Regalia was packed into twenty crates and deposited in a former beer cellar, the tunnels of which led deep into the safety of the rock below Nuremberg’s imperial castle, extending over nine hundred square meters (9,700 ft2). Coincidentally, the emperors’ treasure was stored alongside two works by Nuremberg’s Albrecht Dürer: a portrait of Charlemagne and one of Emperor Sigismund in the Holy Roman Emperor’s coronation dress.14

At war’s end, when the U.S. armed forces assumed control of Nuremberg, Captain J. C. Thomson, a fine arts and archives officer (one of the Monuments Men), was tasked with the responsibility of retrieving and cataloguing the artwork stowed away by the Third Reich administration. Working alongside Dr. Troche, the preservationist at Nuremberg’s Germanic Museum, he soon discovered that the core items of the Imperial Regalia had disappeared, namely, the crown, scepter, orb, and ceremonial swords—symbols of the legitimatization of the Holy Roman Emperor. It was assumed that either the SS or an NS resistance group had spirited the historically significant treasure away.15

A few weeks later, U.S. headquarters in Frankfurt commissioned U.S. officer Walter Horn with the investigation into the disappearance of the artefacts. Two factors aided tremendously in the search: first of all, Walter Horn was born and raised in Germany and was thus a native speaker, and second, during the course of his art and history studies in Heidelberg and Berlin, it just so happened that Horn and Dr. Troche of Nuremberg’s Germanic Museum had been fellow students and friends.16

After several weeks of investigation and the questioning of suspects, Walter Horn obtained a confession from one of the perpetrators, Nuremberg’s air-raid shelter director. He, along with the mayor and a city engineer, had transferred the five missing objects to a different shelter in the old town, where they were concealed thirty-some meters (about 100 ft) below ground, behind two feet of brick and concrete.17

Despite all the efforts made by Nuremberg’s administration to preserve the Imperial Regalia, the care of which the city had been entrusted with by the Holy Roman Empire for 350 years, it was decided that this treasure of extraordinary value—both monetarily and historically speaking—would not remain in “Germany’s Little Treasure Chest.” The Allied Control Board in Berlin conceded to the request of the new Austrian government to have the Imperial Regalia returned to Vienna. This decision followed the guidelines laid down for all objects of value retrieved by the Monuments Men: to return all cultural treasures to their respective prewar locations.18

Today, the near legendary collection known as the Imperial Regalia of the Holy Roman Empire, perhaps the most precious historical legacy in the world, is displayed at the Hofburg Palace’s treasury in Vienna. Duplicates of the crown, orb, and scepter can be viewed at Nuremberg’s Fembo Haus Museum.

Notes

1. Jeffrey Richards, The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages, 476–752 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979), 14–16.

2. James Bryce, The Holy Roman Empire (1878; London: Perlego, 2013), 62–64.

3. Reinhart Staats, Die Reichskrone: Geschichte und Bedeutung eines europäischen Symbols (Kiel, Germany: Ludwig, 2006), 49.

4. Heinz Meyer and Rudolf Suntrup, eds., Lexikon der mittelalterlichen Zahlenbedeutungen (Munich: Fink, 1987), 565.

5. Ibid., 620.

6. Rudolf Distelberger and Manfred Leithe-Jasper, The Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna: The Imperial and Ecclestiastical Treasury (Munich: Beck, 2019), 49.

7. Ibid., 51.

8. Ibid., 55.

9. Sydney Kirkpatrick, Hitler’s Holy Relics (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011).

10. Dagmar Paulus, “From Charlemagne to Hitler: The Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and Its Symbolism,” University College London, 2016, https://cpb-eu-w2.wpmucdn.com/blogs.bristol.ac.uk/dist/c/332/files/2016/01/Paulus-2017-From-Charlemagne-to-Hitler.pdf.

11. Peter Heigl, The Imperial Regalia in the Nazi Bunker (Nuremberg: Edition Mola-Mola, 2005), 39.

12. Ibid., 13–14.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid., 45–46.

15. Ibid., 49.

16. Ibid.

17. Heigl, Imperial Regalia in the Nazi Bunker, 51.

18. Ibid., 63.