Chapter 18

Policing the Reich

From Democracy to Dictatorship

Following Hitler’s appointment as chancellor on January 30, 1933, and just a few days after the Reichstag fire some weeks later, the National Socialists’ paramilitary organizations—the SS and the SA—unleashed an extensive campaign of violence against the Communist Party and any left-wingers, trade unionists, the Social Democratic Party, and the Center Party. Thousands of Communists and Social Democrats were arrested and jailed. In March and April, some forty to fifty thousand political foes were taken into Schutzhaft, so-called protective custody. The SA and SS routinely publicly humiliated, beat up, and tortured political opponents, and they looted, vandalized, or destroyed left-wing parties’ offices and property.1

Prior to the next elections on March 5, 1933, the National Socialist paramilitary organizations implemented terror, repression, and propaganda across the land and “monitored” the voting process. In Prussia, for example, Hermann Göring ordered some fifty thousand members of the SS, SA, and the Stahlhelm to monitor the votes. However, despite having waged a campaign of terror against their opponents, the National Socialists gleaned just under 44 percent of the votes. Two weeks after the election, Hitler succeeded in passing an Enabling Act, which effectively provided him with dictatorial powers.2 Bemoaning the disastrous results of the Weimar Republic’s multiparty government, Hitler’s objective was to remove all political opposition and to create a one-party government.

By the end of May, approximately five hundred members of the municipal administration and seventy mayors were expelled from office, and violence spread to include nonleftist political figures as well. On June 26, Heinrich Himmler, the head of Bavaria’s political police and the leader of the SS, gave orders to place all Reichstag (parliamentary) and state assembly representatives of the Bavarian People’s Party in “protective custody.” On July 14, 1933, Hitler’s regime passed legislation to outlaw all political parties, other than the National Socialist Party, and to forbid the creation of any new political party. By this point, just months after Hitler’s seizure of power, all of Germany’s parties had either been shut down or ordered to dissolve themselves.3

The Terror Apparatus

The National Socialists’ terror apparatus comprised five individual organizations whose common denominator was the use of violence. First and foremost was the Schutzstaffel (protection squad), known as the SS, which formed the system’s main pillar with regard to administration, personnel, and ideology. Second came the police, then the Reichsicherheitsdienst (Security Service of the Reichsführer-SS), also known as RSD or simply SD, followed by the concentration camp system and the department of justice.4

This flexible and coordinated machinery served varying purposes over the years and adapted itself to missions that can be categorized into three phases. In its first phase, the terror apparatus’s principal aim was to ensure the regime’s rule by eliminating political opponents. It also worked at transforming police organizations into an effective instrument of the state’s authority and of Hitler’s personal dictatorship.5

Having achieved its first aims by 1936–1937, the organizations’ next mission was to ready the terror apparatus for going to war and to prepare the German Volksgemeinschaft to this effect. During the war itself, the terror apparatus experienced a widening of its field of operations and a multiplication of its functions. It now was tasked with securing the home front as well as occupied territories from sabotage, resistance activities, and disloyalty. As German troops advanced into Poland and the Soviet Union, the terror organizations carried out attacks on individuals and groups, with the aim of depopulating large areas for the subsequent relocation of German farmers.6

The Rapid Rise of the SS

Actually a subdivision of the National Socialist Party, the SS was officially a registered association. It had begun with a small guard unit known as the Saal-Schutz (hall security) comprised of NS volunteers to ensure security for party meetings in Munich. Hitler wanted this small guard unit to remain separate from the “suspect mass” of the party, including its paramilitary Sturmabteilung (Storm Battalion), commonly known as the SA, which he did not trust.7 In May 1923 the group was renamed Stosstrupp (shock troop), and in 1925, Heinrich Himmler joined the unit, which had by then been reformed and given its final name, Schutzstaffel. From 1929 to 1945, under Himmler’s authority, the SS grew from a tiny paramilitary formation in the final years of the Weimar Republic to one of the most powerful organizations in Third Reich Germany.

The organization comprised two principal groups: the Allgemeine SS (General SS) and Waffen-SS (Armed SS). The Allgemeine SS was tasked with enforcing the National Socialists’ racial program as well as general policing, whereas the Waffen-SS was made up of combat units within Germany’s armed forces. A third constituent of the SS, was the SS-Totenkopfverbände (Death’s Head Units),8 which ran the concentration and extermination camps. Other subdivisions of the SS included the Gestapo (Secret State Police) and the Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service). These were in charge of detecting actual or potential enemies of the National Socialist state, the elimination of any opposition, monitoring the German people for their commitment to National Socialist precepts, and providing domestic and foreign intelligence.

The SS grew rapidly in size and power thanks to its sole loyalty to Hitler, as opposed to the SA, which was viewed as partly independent and a possible threat to Hitler’s authority over the party.9 Already by the end of 1933, the membership in the SS reached 209,000.10 Under Himmler’s authority, the SS organization continued to amass greater power as ever more state and party functions were allocated to its jurisdiction. Eventually, the SS became answerable only to the Führer, a development typical of the organizational structure of the entire NS regime, in which legal norms were supplanted by actions undertaken according to the Führerprinzip (leader’s principle), the premises of which was that Hitler’s will was above the law.11

Although Hitler wielded absolute authority, it was Heinrich Himmler who held the official responsibility for the regime’s terror organizations. His ascent to power commenced with his designation as leader of the SS in 1929, followed by his appointment as commander of the Bavarian political police in 1933. In 1936, he ascended to the position of German chief of police, and subsequently to minister of the interior in 1943. As the overseer of all of the Third Reich’s policing entities, Himmler was ultimately accountable as one of the principal architects of the regime’s ruthless campaign of persecution and extermination targeting both Jews and non-Jews.

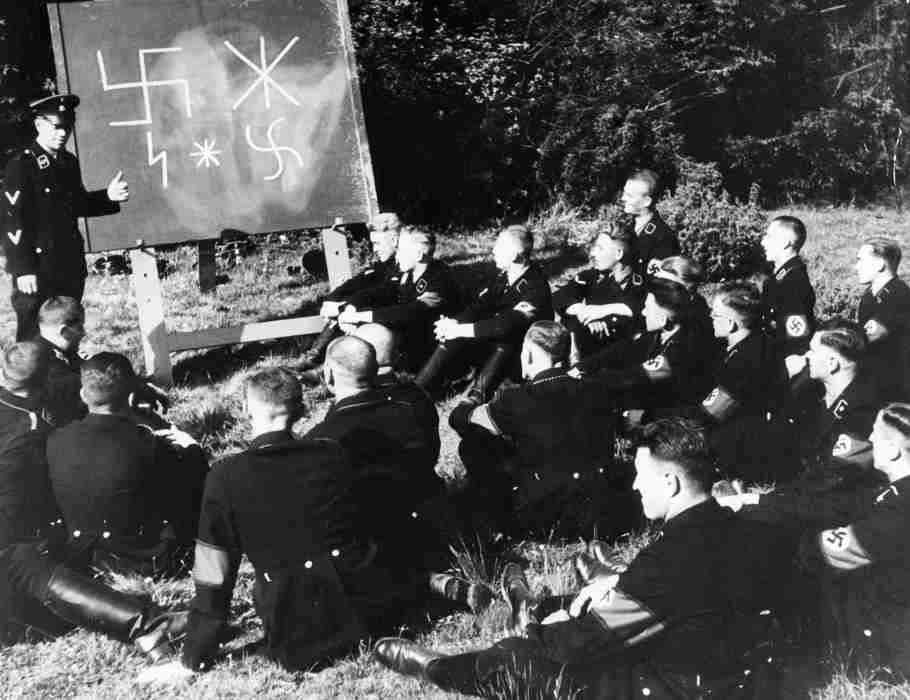

SS Members: Qualifications and Training

The SS motto, “Meine Ehre Heisst Treue” (My honor is loyalty), was engraved on the men’s dress daggers and on their uniform belt buckles. Each new member of the SS was sworn in with the following oath: “I vow to you, Adolf Hitler, as Führer and Chancellor of the German Reich, loyalty and bravery. I vow to you and to the leaders that you set for me absolute allegiance until death. So help me God.”

Himmler envisioned the SS not only to serve as an elite military force but also to set an example as the embodiment of racial purity. Recruits were subject to strict physical requirements and genealogical investigation before acceptance. Enlistees in the Leibstandarte, Hitler’s personal bodyguard unit, had to be between twenty-three and thirty-five years of age, be at least one meter, eighty centimeters (5ʹ11″) in height, and be of German blood and with no criminal record or history of alcoholism. The racial requirements for SS members were based on evidence of Aryan heritage dating back to 1800, for officers to 1750.

Contrary to the SA, which was part of the defense organizations, Himmler required members of the SS to fit the mold of northern Germanic features, an elite within a company of chosen men who incorporated the heroic “ideal.” Viewed as an order of men of superior class backgrounds—emulating Germany’s old aristocracy—the SS attracted many members for this reason. Those who joined were often military officers, freelancers who had lost their source of income due to the economic crisis, or members of the German nobility. SS members were expected to marry by a certain age; however, the prospective partner first had to be certified and approved as “racially pure and hereditarily healthy.” SS members and their wives were required to break their confessional ties with the church and to adopt a National Socialist ideological worldview.12

An “ancestry cult” of the SS was not limited to the organization’s own research into Germanic prehistory through a study group called Ahnenerbe (ancestral heritage) but also encompassed pseudoreligious rituals, consecrations, and the use of cult objects such as the “dagger of honor,” the skull ring, and the Julleuchte (yule lantern). These activities and items were meant to create a substitute religion and new mystical rites for these men and, at the same time, lend the order a quasi-esoteric aura.13 The Julleuchte was an object that played an important role in the process of adaptation from Christian to a nonreligious ritual. It was used primarily during Julfest (Yuletide celebration), which SS members held at the end of the year, in lieu of Christmas. Himmler gave all married SS men yule lanterns as gifts—each came with an accompanying certificate claiming it was a replica of a piece “from the early history of our people.” In fact, these lanterns were an exact imitation of Swedish candleholders from around 1800.14

In an effort to professionalize their officers, the SS founded a leadership school in 1934; the first one was located in the Bavarian town of Bad Tölz, a second school in Braunschweig, and others were created soon after. Himmler employed experienced military veterans and skilled officers to build a training regimen that became the foundation for the Waffen-SS.15 In 1937, Himmler rechristened the leadership schools Junker (pronounced “Younker”) Schools in honor of the landowning Junker aristocracy that once dominated the Prussian military.

The schools aimed to train and mold the next generation of leadership within the SS: cadets were taught to become adaptable officers who could perform any task assigned to them, be it in a police role, at a concentration camp, as part of a fighting unit, or within the greater SS organization.16 Personality coaching was emphasized, which meant that future SS leaders and officers were shaped, above all else, by a National Socialist Weltanschauung. Education at the Junker Schools was aimed at communicating a sense of racial superiority, creating a bond to other dependable like-minded men, ruthlessness, and a toughness that concurred with the value system of the SS. Throughout their training, cadets were continuously monitored for their “ideological reliability.”17

Part of the SS members’ worldview education consisted of learning about Nordic runes.18 The jagged, lightning-bolt double S insignia of the SS was one of such runes called Sig drawn from Guido von List’s Armanen Order. In ancient Norse and Germanic rune lore, the Sig rune signified the sun: its Elder Futhark reconstructed name was sowilo, “sun”; Younger Futhark name was sól, “sun”; and Anglo-Saxon Futhorc name was sigel, “sun” (Elder and Younger Futhark represent two forms of the old German/Norse alphabet, known as runes, and the Futhorc is the old English runic alphabet). Guido von List changed the name to mean “victory” (Sieg in German). In National Socialist Germany, Sig or the Siegesrune (rune of victory) was the most recognizable and widely used symbol after the swastika. The SS rune insignia with two oblique Sig runes was created in 1933 by the penniless graphic designer Walter Heck, who received two and a half Reichsmarks for the rights to this design.19

The Brownshirts

Hitler founded the Sturmabteilung (Storm Detachment), also known as the SA, in Munich in 1921, drawing its initial membership from various thuggish individuals who had aligned themselves with the budding National Socialist movement. Many of the early recruits were former members of the Freikorps (a volunteer militia group), armed opportunistic factions, and ex-soldiers who had engaged in street battles with leftist groups in the nascent days of the Weimar Republic. Sporting brown uniforms, similar to the fashion of Mussolini’s Fascist Blackshirts in Italy, the SA was charged with safeguarding party members at meetings, participating in National Socialist marches, and physically assaulting political adversaries.

Provisionally in disarray after the failure of Hitler’s Munich Putsch in 1923, the SA was restructured in 1925 and rapidly resumed its violent activities, intimidating voters in national and local elections. From January 1931, it was led by Ernst Röhm, who embraced radical anticapitalist ideas and dreamed of turning the SA into Germany’s main military force. Under Röhm, SA membership swelled with the ranks of the Great Depression’s unemployed, growing to four hundred thousand by 1932 and possibly to two million—twenty times the size of Germany’s legally authorized army—by the time Hitler came to power in 1933.20

In the early days of the National Socialist government, the SA engaged in unbridled street violence against those who opposed the National Socialists. However, it was regarded with suspicion by the regular army and influential industrialists, both groups whose support Hitler was striving to obtain. Despite Hitler’s objections, Röhm persisted in advocating for a “second National Socialist revolution” of a socialist nature, and he sought to merge the regular army with the SA under his personal leadership. On June 30, 1934, a day later referred to as “the Night of the Long Knives,” Hitler ordered the SS to carry out a “blood purge” of the SA leadership. Röhm and numerous SA leaders were summarily executed. In the wake of this event, the SA’s strength significantly diminished, and it no longer played a major political role in the regime. From 1939 onward, the SA was relegated to training all able-bodied men for home guard units.21

The Force of the Police

When Himmler was appointed Reichsführer SS and chief of the German police in 1936, the police, still formally organized as a federal entity, was assimilated into the Reich. Himmler held sway over the Reich’s three police forces: Ordnungspolizei (Orpo), “regular police”; Sicherheitspolizei (Sipo), “security police”; and Sicherheitsdienst (SD), “security service.”

In 1939 the Sipo and SD were merged to form the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA), Reich’s Main Security Bureau.

When the National Socialists came to power, a good portion of the police force grew wary of the party’s objectives. National Socialist protests and violence, particularly in the last years of the Weimar Republic, had been rebellious, and the police had carried out thorough and repeated investigations of both the National Socialists and the Communists. Despite the National Socialists’ history of public agitation, Adolf Hitler professed his respect for law and order and promised to uphold traditional German values. The police and other conservatives looked forward to the widening of police power resulting from a strong centralized state, welcomed the end of factional politics, and agreed to end democracy.22

The NS regime lessened the workload and challenges that the police had faced during the Weimar Republic. By censoring the press, Hitler’s regime shielded the police force from public disapproval. With the banning of the Communist Party, as well as other factions, street brawls had been eradicated. Police manpower was widely extended thanks to the integration of the National Socialists’ paramilitary organizations as an auxiliary police force.

The new regime centralized and fully funded the police to better control criminal gangs and to ensure state security. The NS state increased staff and training and went about updating police equipment. The Third Reich’s policies granted the police departments unprecedented liberties regarding arrests, incarceration, and the treatment of prisoners. Police officers could now take “preventive action,” that is, make arrests without any evidence required for a conviction in court, and detainees had no recourse to legal representation.23

Through centralized authority and the assimilation of the SS and its organizations within the police departments’ infrastructure, the NS leadership seized complete control of the once traditional police and transformed it into an instrument of state repression and, eventually, of genocide.24

Gestapo: The Secret State Police

Though officially an organ of the Reich’s Home Office or Department of the Interior, the Geheime Staatspolizei or Gestapo, created in April 1933, was a special agency that defined its own tasks and jurisdiction. The Gestapo served as an instrument of the Führer’s authority and, pledging unwavering loyalty to Hitler, carried out his orders regardless of what measures this would imply. It functioned as a normal police department as well, but often resorted to acts of terror.25

The Gestapo’s ideological premise was to ensure the German people’s “right to live,” to maintain its population, and to further its existence. In practice, the organization did not attempt to monitor the entire German population but rather aimed at eliminating any political opposition and hunting down and liquidating racial minorities. To this effect, the Gestapo’s two main tools were Schutzhaft and Sonderbehandlung.26

Schutzhaft (protective custody) was not unique to the Gestapo but was quickly adopted as their policy. Unlike the former definition of this type of confinement, by which the detained subject was to be granted protection, it was now the “people and the state” that were to be protected by imprisoning the inmate. In the beginning, protective custody was carried out in state prisons; later, however, the suspect was often interned in a concentration camp.

Sonderbehandlung (special treatment) was the code name for the administrative order to execute a prisoner. “Special treatment” was introduced and implemented against Poles by Reinhard Heydrich at the outset of the Polish campaign, in other words, during the first days of World War II. Eventually, the true meaning of Sonderbehandlung remained no longer a secret, so the term Evakuierung (evacuation) replaced it, especially in subsequent Jewish extermination operations.27

The SD: Top Security

The ideological elite, according to Himmler and Heydrich, comprised of the best members from both the SS and the police force, constituted the branch known as the Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführers-SS (Security Service of the Reich’s SS Leader). This organization served as the intelligence-gathering agency for the SS and was responsible for safeguarding Hitler and other high-ranking officials. Prior to 1937, the activities of the SS and Gestapo overlapped, but they were subsequently clearly distinguished. One of the SD’s primary duties was to examine international organizations and intellectual movements that were deemed adversarial, with the help of informants from all segments of society. During the war, the SD played a significant role in the elimination of Jews and other civilian groups residing in territories occupied by German forces.28

The Legal System

Under National Socialism, many of the freedoms enjoyed by Germans during the Weimar Republic were quickly curtailed. The party’s grip on the legal system made it almost impossible to oppose the regime. Judges were compelled to pledge loyalty to Hitler and were expected to act solely in the interests of National Socialism. Lawyers were required to join the National Socialist Lawyers’ Association, which subjected them to close scrutiny. The role of defense lawyers in criminal trials was significantly diminished, and standardized penalties for crimes were abolished, leaving it to local prosecutors to determine appropriate punishments for those found guilty. As an example, the number of capital crimes increased from three to forty-six. These measures reduced the number of criminal offenses by over fifty percent between 1933 and 1939. However, many convicts were not released at the end of their sentences but instead transferred to the growing number of concentration camps established by the SS.

Sondergerichte (special tribunals) were set up throughout the nation and were responsible for all offenses that fell under the provisions of the Reichstag Fire Decree or the laws regarding “acts of treachery.” The main aim of these courts was to drastically shorten proceedings and to strengthen the prosecuting attorneys’ powers. It was not possible to lodge an appeal against the decisions of these special tribunals. From 1938 on, any offense could legally be appointed to one of these courts. Four days after Germany’s invasion of Poland a law was passed, the Volksschädlingsverordnung (ordinance on antisocial parasites), by which any offense, no matter how petty, could legally be punishable by death. During the war years, the number of “special courts” increased from twenty-six to seventy-four.29

The Reich’s entire terror apparatus, from the police to the Gestapo, was also reinforced by a vast network of informants and collaborators, who were encouraged to report on their neighbors, friends, and even family members if they were suspected of opposing the regime. Overall, the policing organizations in Germany played a central role in the NS dictatorship’s efforts to control and terrorize the population, and it eventually became a key tool in the Reich’s campaign of genocide and ethnic cleansing during the Holocaust.

Notes

1. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “Nazi Political Violence in 1933,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/nazi-political-violence-in-1933.

2. Evans, Coming of the Reich, 317–39.

3. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “Nazi Political Violence in 1933.”

4. Volker Dahm, “Der Terror- und Vernichtungsapparat,” in Dahm, Die Tödliche Utopie, 322.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Chris McNab, The SS, 1923–1945 (London: Amber Books, 2009), 14–16.

8. Ibid., 137.

9. Shelley Baranowski, Nazi Empire: German Colonialism and Imperialism from Bismarck to Hitler (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 196–97.

10. Christian Zentner and Friedemann Bedürftig, The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (New York: Macmillan, 1991), 901.

11. Ibid., 903.

12. Dahm, “Der Terror- und Vernichtungsapparat,” 279–80.

13. Ibid., 280.

14. Wulff E. Brebeck, Matthias Goldmann, and Kreismuseum Wewelsburg, Endtime Warriors: Ideology and Terror of the SS (Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2015), 147.

15. Adrian Gilbert, Waffen-SS: Hitler’s Army at War (New York: Da Capo Press, 2019), 21–22.

16. Adrian Weale, Army of Evil: A History of the SS (New York: New American Library, 2012), 206–207.

17. André Mineau, SS Thinking and the Holocaust (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2011), 29.

18. Dahm, “Der Terror- und Vernichtungsapparat,” 328.

19. “Norse Rune Symbols and the Third Reich,” The Viking Rune, https://www.vikingrune.com/2009/07/norse-runic-third-reich-symbols/.

20. “SA: Nazi Organization,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, July 15, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/topic/SA-Nazi-organization.

21. Ibid.

22. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “German Police in the Nazi State,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/german-police-in-the-nazi-state.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. Dahm, “Der Terror- und Vernichtungsapparat,” 336–37.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid., 338–39.

28. Ibid., 344–45.

29. Ibid., 360.