Chapter 29

Neo-Nazis in Germany Today?

How Have Germans Changed since 1945?

The media repeatedly spotlights and justifiably scandalizes far-right or “neo-Nazi” demonstrations and acts of violence taking place in Germany. Should such events be read as proof that the country is still, or becoming again, racist? To better discern to what extent Germans might be pro-Nazi or xenophobic in the twenty-first century, a number of key historic developments from 1945 to the present need to be addressed.

After the Cold War ended and the East and West were reunited in 1990, Germany rose to become the foremost leader in Europe. However, there exists a persistent undercurrent of xenophobia in Germany that has led to incidents of aggression ranging from mob attacks to mass murders. Notably, a significant portion of this violence has occurred in the East or has been carried out by individuals from former East Germany. According to the Federal Ministry of the Interior, in 2014 almost half of the 130 reported antiforeigner crimes in Germany occurred in the East, despite the fact that only 17 percent of the population lives in the “New States.”1 This chapter also aims to examine the policies and development in the “Two Germanys” since their reunification, particularly with respect to xenophobia.

Following the crushing of Hitler’s National Socialist regime in 1945, the Allied Powers attempted a denazification of the German Volk and led the drive to bring NS criminals to justice. Both the Allies and the Germans faced the challenge of safeguarding freedom and democracy, as well as dealing with the moral burden of National Socialism, the Holocaust, and widespread devastation in the country. The western regions of Germany received support from their Allies, but the Soviet-occupied zone faced greater difficulties. The resulting Cold War led to the establishment of two German states with different political ideals and mutual animosity.2

Justice and Denazification in West Germany

After the war ended, it was not challenging for interregnum officials to repeal the laws of the previous regime, erase its symbols and slogans from public life, remove unwanted books from Germany’s libraries, eliminate swastikas from forms and paperwork, and rename streets.3 However, the significant challenge ahead was to alter the mind-set and beliefs of not only the millions of members of the National Socialist Party and its various organizations but also the rest of Germany’s citizens who had been indoctrinated by Hitlerian propaganda for twelve years.

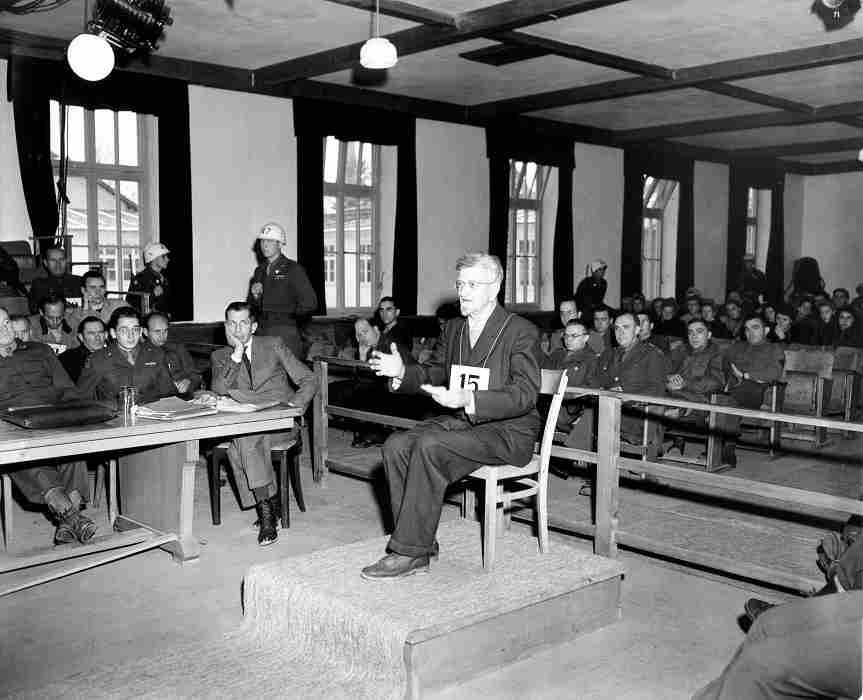

Aside from the well-known Nuremberg Trials, which coordinated the hearings of twenty-one leaders and 177 military defendants, over one hundred thousand Germans and Austrians across Europe were held responsible for their involvement in Third Reich crimes. These numbers account for only those who were convicted out of nearly four hundred thousand Germans and Austrians who were detained on suspicion of committing National Socialist crimes or war crimes.4

While legal proceedings such as those at Nuremberg or the Dachau Trials for crimes against humanity were judicial hearings of specific crimes, denazification would have to use a different methodology. The first aim was to politically cleanse German society and ensure that those who had been active in applying the ideology of the NS regime were barred from important posts in society and state institutions. The German Law 104 for Liberation from National Socialism and Militarism of March 5, 1946, established five categories for the classification of Germany’s citizens: major offenders, offenders, lesser offenders, followers, and exonerated persons.5

As the truth about the appalling conditions in concentration camps within Germany as well as the mass extermination in the Reich’s death camps in Eastern Europe came to light and the public was shown shocking film footage, ideas of shared guilt and the possibility of collective punishment for the German people began to emerge. The populace as well as returning soldiers were forced to confront the reality that millions of individuals, including six million Jews, nearly half a million Sinti and Roma, hundreds of thousands of hospital patients, three million Soviet prisoners of war, and at least 130,000 non-Jewish Polish civilians, had been killed as a result of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Faced with these disturbing truths, many individuals attempted to deny responsibility or sought leniency by claiming that they had been “seduced” by the regime’s promises and placing all the blame on the “major war criminals.”6

In order to project a truthful representation of National Socialism on the German population as part of the postwar denazification efforts, the Allies launched a psychological propaganda campaign with the aim of developing a German sense of collective responsibility.7 With the support of the German press, which fell under Allied control, as well as posters and pamphlets, a program was carried out by which ordinary German citizens were informed of the horrors of the concentration camps. Posters were propagated, displaying images of concentration camp victims matched to texts such as “You Are Guilty of This!”8 or “These Atrocities: Your Fault!” Thousands of Germans who lived near concentration camps in Germany were led through the camps to witness with their own eyes the crimes that had been committed by the regime that these people had supported. In addition, several films, such as Die Todesmühlen (The Death Mills), were produced with the aim of disclosing to the German public the reality of the concentration camp system.

In March 1946, the Allied Powers turned responsibility for denazification over to the German authorities. The accused had to provide detailed and truthful information about their political biography, including membership in the National Socialist Party or any other affiliated organization. The sanctions imposed included fines, forced retirement, or even confinement to a labor camp. Due to the scarcity of incriminating documents, an overwhelming majority of cases were classified in the fourth category of “followers.” Only 1.4 percent of the accused undergoing denazification were classified “major offenders” or even “offenders.”9

In the early period of denazification, the Allies’ aim was to investigate every suspect and hold every supporter of National Socialism accountable. Soon, however, they realized that the number of suspects and the lack of qualified personnel simply made this goal unrealistic. It was also reasoned that pursuing denazification too thoroughly would hinder the creation of a functioning, economically efficient, democratic society in Germany. The Morgenthau Plan had recommended that the Allies construct a postwar Germany devoid of industrial means and reduced to a level of subsistence farming. The plan was soon deemed impracticable because of its excessive punitive measures that were likely to engender German anger and rebellion.10

Within a few years, a more important consideration that led to the tempering of the denazification effort in the West was the need to prevent the German population from turning to Communism.11 As the Cold War commenced, Great Britain and the United States began to view West Germany as a crucial ally, and denazification was rapidly trimmed down in an effort to foster amicable relations between the occupying forces and the local population. Contemporary American critics of denazification decried it as a “counterproductive witch-hunt” and a failure. In 1951 the provisional West German government granted amnesties to lesser offenders and terminated the program.12 Many convicted criminals were pardoned, and doctors guilty of the murder of patients returned to their medical careers. Former National Socialist judges and even members of the terror apparatus were allowed to resume employment in the police force or public service.13

The German Federal Republic from 1949 to 1990

In 1945 defeated Germany was split into four occupation zones, controlled by the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. In 1948, the Soviet Union blocked western access to Berlin, prompting the western powers to form a new federal state in the three western occupation zones. This new state, known as the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), was established in May 1949 with its capital in Bonn. “West” Germany was initially governed by a provisional constitution, and Konrad Adenauer, a Christian Democrat, was appointed as its first chancellor. Prior to 1933, Adenauer had held prominent positions in the political hierarchy of the Weimar Republic, which led to his exclusion and persecution by the National Socialist regime.

The first president of the newly established Germany was Theodor Heuss, a liberal politician who had previously worked as a political journalist. Throughout Hitler’s regime, Heuss had maintained close relationships with a network of liberals and established contact with the German resistance toward the end of the war, although he was not an active resister himself. While both Adenauer and Heuss shared a deep disdain for National Socialism, the new government shifted the nation’s focus from denazification to recovery, guiding the country from the devastation of war toward becoming a productive and prosperous nation that fostered amicable relations with its former adversaries, including France, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

During the period from 1949 to 1959, when many Germans sought to forget about the National Socialist past, Heuss used his position as federal president to draw attention to the crimes of the NS era and bring it into West German national political discourse. With no electoral pressures, he addressed the “collective shame” of the Third Reich era, the value of the legacy of the German resistance, and the genocide of German and European Jewry. He regarded accepting the burden of the nation’s recent past as a sign of bravery, responsibility, and patriotism, and avoiding it as an act of cowardice and a betrayal of German moral obligations.14

In 1948, as part of a scholarly survey, West German adults were posed the question, “Do you believe that National Socialism was a good idea that was executed poorly?” The results were striking, with 57 percent responding in the affirmative, 28 percent in the negative, and 15 percent being undecided. Nearly four decades later, in 1985, the same German scholars studied the viewpoints of individuals born prior to 1932 and discovered that 56 percent of respondents acknowledged having faith in National Socialism at some point, 32 percent denied having held any such beliefs, and 11 percent “had no recollection.”15

Although Adenauer’s government generally prioritized Germany’s future over its past, a significant number of suspects had yet to face trial. By the late 1950s, West German prosecutors and scholars estimated that approximately one hundred thousand individuals had played some role in the devastation of European Jewry. From 1945 to the mid-1980s, Allied and then West German courts accused 90,921 individuals of committing war crimes or crimes against humanity. Among them, 6,479 were found guilty, with 12 being executed, 160 sentenced to life in prison, 6,192 given extended prison terms, 114 paying fines, and 83,140 cases being closed without any convictions.16

Although denazification and punishing National Socialist criminals or collaborators ceased being top priorities for West German leadership by the 1960s, Vergangenheitsbewältigung continued to be a significant concern. This compound German noun describes the process of facing and overcoming the past, which remained an ongoing task that the West German leadership considered essential. Further discussion of this topic will follow later.

The German Democratic Republic from 1949 to 1990

The postwar Communist debate on the memory of the Jews took place during the period between the end of Hitler’s rule and the beginning of the Cold War, a time of self-searching and adjustment known as the Nuremberg interregnum. The German Communists and Soviet occupation authorities considered Soviet suffering, subsequent triumph, and the narrative of Communist martyrdom as the central aspects of postwar commemoration. For many of them, the memorialization of the Holocaust loomed as an unwelcome competitor for the limited resource of postwar recognition. The preference for Communist “fighters” over Jewish “victims,” the emphasis on Soviet suffering and redemptive victory at the expense of the Holocaust, and the delayed and subsequently rejected requests for restitution payments to Jewish survivors were all discouraging signs for Jewish Communists and their non-Jewish comrades.17

Many East Germans perceived the Russians’ “liberation” of the eastern part of the country in 1945 as an ignominious injustice. While the Soviets primarily used denazification statutes to detain National Socialist officials, they also arrested a significant number of Germans, including women and children, who had no involvement in National Socialism in any administrative or other capacity. Many Germans were detained for extended periods without trial or subjected to unfair trials resulting in extremely severe sentences, often involving forced labor. The Soviets imprisoned at least 130,000 Germans on the grounds of denazification directives in so-called Special Camps, where at least 43,000 individuals perished.18

The East German government (GDR) claimed to be an antifascist state and thus exempt from the need to confront the specter of Third Reich history—since there could be no place for xenophobic hatred in such a state. The puppet government, as part of its indoctrination themes, allegedly underwent a radical antifascist and democratic transformation, which it referred to as an antifaschistisch-demokratische Umwälzung, a radical antifascist, democratic turnaround. This mind-set asserted that complete denazification, anti-imperialism, and genuine democratization were only possible in Germany under Soviet control. As a consequence, the West German government was landed with the status of National Socialist Germany’s successor state, leading to the difficult task of addressing the damaging legacy of the former dictatorship.19

The German Democratic Republic addressed the national guilt of the Third Reich through the propagandic promotion of a new national identity emphasizing antifascism and resistance to oppression while celebrating local heroes. It also attempted to minimize the role and responsibility of East Germans during the National Socialist era by underlining their victimization under Hitler’s regime. In addition, the GDR implemented reparations programs, compensated victims, and established memorials and museums to commemorate them. Despite these measures, the government faced international criticism for its handling of the NS regime’s legacy, with some accusing it of failing to take sufficient responsibility for East Germans’ role in Hitler’s authoritarian regime.

The GDR viewed fascism as a form of capitalist exploitation, with antisemitism and racism considered secondary or incidental manifestations. Consequently, East German representations of concentration camp life under National Socialism did not focus on racial persecution, whereby Jews, Sinti, and Roma were largely excluded from commemorative representation. During remembrance ceremonies, the pogrom was primarily associated with Communist bravery, while Jewish suffering was considered a secondary concern.20

Given that for four decades the GDR benefited from a supposedly international-minded government, the question arises as to why xenophobic violence is more prevalent in the East of Germany today. In contrast, during the same period and after the war, successive generations of West Germans became significantly less racist, while their East German counterparts became increasingly xenophobic.21

Prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989, the GDR had brought in a significant number of Mozambican and Vietnamese contract workers. However, the East German government imposed administrative controls that isolated these fifteen thousand Mozambican workers from civil society. They were sequestered in buildings on the outskirts of cities, and those who violated regulations faced being sent home. Female contract workers who became pregnant were given only two options: either terminate the pregnancy or return home. These policies contributed to around 60 percent of East Germans stating that they had no contact with foreigners and little knowledge about them.22

Since the 1990 Reunification: Germany’s Immigrant Population

To address the labor shortage in postwar West Germany, the German Federal Republic began inviting Turkish guest workers in 1961. While some returned home, many stayed, resulting in a growing population of individuals in Germany with Turkish roots. As of 2020, estimates vary between 3.5 and 7 million people of Turkish descent living in Germany, a large percentage of whom were born in the country.

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, emigration from its successor states surged in the 1990s. Between 1990 and 1999, Germany welcomed around 1.63 million ethnic Germans and 120,000 Jews from the former Soviet Union.23

In 2015 and 2016, a significant influx of refugees fleeing conflict and terrorism in Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq arrived on Europe’s shores, sparking fear and uncertainty regarding who would provide asylum and how to integrate these individuals. Despite this, German Chancellor Angela Merkel remained resolute and declared in August of that year, “We can do this!” Germany received more than one million first-time asylum applications, and five years later, over half of these refugees had secured employment: in Germany’s “Old States,” public backing for immigration remains strong.24

Though the 2015–2016 immigrant surge drew worldwide attention, the country has long been a major immigrant destination. Over 15 percent of the eighty-three million people living in Germany today are foreign born, a number that increases to 20 percent if the German-born children of immigrants are included. Since the early 2000s, Germany has experienced a significant policy shift toward recognizing its status and becoming a country that aims at the integration of newcomers and the recruitment of skilled labor migrants. This approach to immigration and immigrants has been tested, however, amid the massive humanitarian inflows that began in 2015 and which have stoked heated debate.25

Jews in Germany Today

Out of the approximately 250,000 Jewish displaced persons who passed through Germany in the postwar period, roughly 10 percent opted to stay in the country. The largest and most noticeable group of Jews living in Germany immediately after the war were those who were Eastern European displaced persons. They were accompanied by a small cohort of German Jews, approximately fifteen thousand of whom were liberated in 1945, some from hiding and others from concentration camps. Many of these German Jews had minimal prior contact with Jewish communities before 1933 and had survived due to the protection of a non-Jewish relative.

Despite these difficulties, a significant number of Jewish communities were established in the postwar years. The Jewish community of Cologne even resumed activities before the end of the war, in April 1945. By 1948, over one hundred Jewish communities had been established, with a total membership of about twenty thousand people. The Jewish population in Germany was thus divided into two distinct groups: a large number of Eastern European displaced persons who came to Germany by chance and often expressed a desire to depart as soon as possible, and a smaller group of German Jews who had been wholly assimilated and had connections to their non-Jewish surroundings.26

Between 1993 and 2021, around 219,000 Jews, including their partners and children, immigrated to Germany from the former Soviet Union.27 Though it is unclear how many remained in Germany, some experts assess the number of Jewish or part-Jewish residents of Germany to be around 225,000 today, an estimate that remains difficult to confirm. Though only ninety-two thousand Jews officially belong to the official Jewish community,28 it is safe to say, however, that Germany’s Jewish community is now the third largest in Europe, after those of France and Great Britain.29

Starting in 1957, the Federal Republic of Germany has provided funding for half of the costs associated with ensuring the safety and monitoring of deserted Jewish cemeteries within the country. In 2020, the government approved a subsidy of twenty-two million euros to the Central Council of Jews in Germany for the execution of structural and technical safety measures in Jewish facilities throughout the nation. Furthermore, the council is in charge of conserving the cultural heritage of German Jews, as well as carrying out social and integration initiatives. The government provides an annual donation of thirteen million euros to support these endeavors.30

Stolpersteine

German stumbling stones, Stolpersteine in German, are small, commemorative brass plaques that are embedded in the sidewalks of German cities and towns. They are designed to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust, particularly Jews who were deported and murdered by the National Socialists during World War II.

The stumbling stones were created by the German artist Gunter Demnig in 1992. Each plaque is about ten centimeters by ten centimeters (4 in by 4 in) and is engraved with the name, date of birth, and fate of a victim of the Holocaust. The plaques are placed outside the last known address of the person being commemorated, creating a visual representation of the scale of the tragedy and the extent to which it affected local communities.

The stumbling stones are designed to make people stop and pay attention as they walk through their neighborhoods and to remind them of the horrors of the Holocaust that took place on the very streets they walk on every day. The stones also encourage people to reflect on the lives of those who were targeted and to consider the impact of discrimination and prejudice on individuals and communities.

The Stolpersteine project has spread across Germany and to other countries in Europe, with over seventy-five thousand plaques installed as of 2021. While some controversy surrounds the placement of the plaques, with some arguing that they are inappropriate for public spaces, many people believe that they are a powerful and necessary reminder of the atrocities of the Holocaust and of the importance of remembering and honoring its victims.

Postreunification: What about the “Neo-Nazis”?

East Germany’s ongoing xenophobia causes significant repercussions in today’s society, especially for nonwhite foreigners. The GDR’s social identity was earmarked by fixed boundaries that established citizens’ inclusion in, or exclusion from, society. The image of what it means to be (or to appear) German is still constrained by a very specific set of characteristics.31

The German neofascist movement has been predominantly concentrated in East Germany since the latter half of the 1990s, displaying an expanding organizational network and gaining increasing traction in local and federal elections. The success of these parties can be attributed to their tendency to offer facile solutions to intricate issues, and their position on the fringe allows them to make lofty promises without the constraints of governing.32

On a political level, two far-right parties stand out in modern Germany. The first is the Alternative for Germany (AfD), a far-right political group known for its opposition to the EU and to immigration. It experienced a decline in the national vote share in the 2021 federal elections but remains the largest party in some parts of eastern Germany.33 In March 2022, the AfD was classified by the German Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution as a suspected right-wing extremist group and a threat to democracy, allowing for ongoing surveillance.34

The unexpected success of the AfD in eastern Germany is primarily attributable to post-1990 events and experiences rather than an inherent xenophobia. Given their weaker economy, limited job opportunities, and lower wages compared to the western states, it is an observable fact that East Germans feel dissatisfied with the Berlin government. Much of their industry is owned by entities from the West or abroad, and many of their once-thriving communities have become ghost towns after numerous East Germans moved to the western states in the early 1990s seeking better employment opportunities. The prospect of heightened competition in the job market and the social upheaval that resulted from the influx of refugees in 2015 and 2016 have undoubtedly drawn many East Germans to the AfD, a party that vowed to defend their rights and livelihood.35

These circumstances, coupled with inferior representation compared to their western counterparts, have spurred East Germans to stage protests. The location and organizational source of all rallies in Germany, often not emphasized in media reporting, reveal that a majority of right-wing rallies are indeed held in the eastern part of Germany, with significantly higher participation rates than in the West. The rallies largely focus on the topic of refugees and issues of asylum, immigration, and exclusion of Muslims, with 80 to 85 percent of all rallies covering these issues.

Established in 1964, the National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD) is the second-largest far-right party in contemporary Germany, espousing a more radical stance of neo-Nazism and ultranationalism. Although efforts were made to outlaw the party, in 2017 the Federal Constitutional Court declined the petition to prohibit it, asserting that the NPD lacked the capability to undermine democracy in Germany. In the 2021 federal elections, the NPD garnered approximately 1 percent of the nationwide vote.

The creation and dissemination of pro-Nazi materials is prohibited under German law. Despite this, such paraphernalia has been illegally imported into the country for many years. Even though neo-Nazi music bands such as Landser have been banned in Germany, counterfeit copies of their albums produced in the United States and other nations continue to be circulated in the country. German neo-Nazi websites frequently rely on Internet servers located in Canada and the United States. They often employ symbols that resemble the swastika and incorporate other NS emblems, such as the sun cross, wolf’s hook, and black sun.

Islamophobia or Hostility to Muslims?

The Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (Federal Agency for Political Education) defines “Islamophobia” as the fear of Islam as a religion. However, what we are currently witnessing in numerous European nations is not so much a fear, criticism, or hatred of Islam as a faith but rather a feeling of resentment to those who follow the religion, namely, Muslims. In other words, the term “hostility to Muslims” is more appropriate to describe the attitudes prevalent in Germany today, akin to the antisemitic sentiments of the first half of the twentieth century.

On a statistical level, according to a study of the Leibnitz Institute for Social Sciences in 2003, about 70 percent of respondents rejected the statement, “Muslim culture definitely fits into our Western world.” But likewise, the majority of respondents, 65 percent, rejected the statement, “I am more suspicious of people of Muslim faith.” According to these results, there are both empirical as well as theoretical reasons for making a clear distinction between the dislike of Islam and hostility toward Muslims.

The survey also revealed that just under half of people in Germany agree with the statement, “The many Muslims here sometimes make me feel like a stranger in my own country.” The 2020 Leipzig Authoritarianism Study found that just under half of people in Germany feel like strangers in their own country due to the presence of Muslims, and at least 25 percent believe that Muslim women should not be allowed to immigrate. In eastern Germany, the latter figure is even higher, around 40 percent. Furthermore, more than half of Germans perceive Islam as threatening.36

Anti-Muslim discrimination is a serious problem in Germany, and it manifests itself in various forms of Islamophobia. This includes negative attitudes and prejudices toward Muslims and “Islam” in various areas of life, including the job and housing market, education, and public spaces. Studies have also shown that anti-Muslim discrimination has a real impact on the job market, particularly for Muslim women who wear headscarves. A 2016 study by the Research Institute on the Future of Work (IZA) found that headscarf-wearing Muslim women with Turkish names had to apply four times as often as equally qualified applicants without headscarves and with German names to be invited for an interview. Islamophobic crimes are also a serious concern in Germany, with reports of attacks on mosques and other religious institutions. In 2020, authorities registered at least 901 Islamophobic crimes nationwide, some of which were attacks on religious institutions and places of worship. In 2019, the German Ministry of the Interior listed ninety-five attacks on mosques.37

The German government and civil society organizations have taken strong measures to combat the spread of neo-Nazism and far-right extremism. German authorities are vigilant and have taken significant steps to address hate speech, xenophobia, and any attempts to undermine the country’s democratic principles. It can be said that, keenly aware of its historical stigma, Germany is making sincere and concerted efforts to expose the perpetrators of the National Socialist regime and to warn younger and future generations of the dangers of extremist policies.

Vergangenheitsbewältigung: Coming to Terms with the Past

Following 1989, East Germans were confronted with the realization that elder National Socialists had also found refuge in the GDR after the war. They also discovered that antisemitism and neofascism were not alien to the “first Socialist State on German soil” and that some of their own grandparents may have been less innocent than they had professed.38

The East German government did not exhibit the same level of antisemitic ideology as the National Socialist regime that preceded it; however, it did not demonstrate the expected level of sympathy or compassion that might be expected from any German government following the Holocaust. This indifferent attitude was evidenced by the unfounded accusations during the GDR’s anticosmopolitan campaigns as well as by the government’s failure to provide adequate recognition and compensation to Jewish survivors and to pursue a comprehensive program of trials for National Socialist crimes during the 1950s.39

In the post–World War II years, despite some political leaders suggesting that public discussion of Jewish matters should have occurred in the Soviet occupation zone, it was, as we witnessed, in the western zones and, later, in West Germany where antisemitism and the Holocaust became a central topic of public discourse. The West German government provided financial restitution to Jewish survivors, established relations with Israel, and prioritized the memory of the Holocaust in national politics. In contrast, GDR leaders kept the Jewish question on the margins of narratives of the NS era, refused to provide restitution or support to Israel, and even supported Israel’s adversaries.40

West Germany, on the other hand, made restitutions to victims and their families under the German Restitution Law, with the equivalent of 7.5 billion euros paid out and an additional 1.25 billion euros granted under a German-Israeli agreement in 1962. The world having projected an image of collective guilt on the Germans in general, and on West Germans in particular, today’s third generation finds itself in the challenging position of having to regularly face and often accept negative social comparisons concerning Germany’s history, even though they were born long after the events.41

Remembering the National Socialist regime itself has a patchy history in West Germany. Until the 1960s, the topic usually drew a general silence, and people neither wanted to know or hear about their own crimes or lack of action. The situation began to change when the country’s younger generation started questioning—and accusing—their elders. In 1979, the American television series Holocaust was viewed by millions of people in West Germany. Amazingly, at that time, the term “Holocaust” was still unknown to most Germans. The series exerted a tremendous impact and long-lasting effect on German society.42 Not only have citizens of West Germany gradually assumed greater accountability for the persecution of Jewish people, but in 1990 the GDR issued a formal apology to the Jewish people and to Israel for the role that many East Germans played in the atrocities committed by the NS regime during World War II. This apology was seen as a significant gesture of reconciliation and an important step toward healing past wounds.43

Germany’s collective shame is not just a set of characteristics but also a process of evolving toward a more positive and acceptable identity. The National Socialist past of Germany and Austria, like many other nations’ histories, is an ongoing legacy that shapes their political and social culture and influences their identity and self-image. The political and moral choices made by Germans in response to their historical legacy have become a significant story of our time, particularly as European unification brings former adversaries together in the shadow of the two world wars.44

In West Germany, the common tendency was to attribute National Socialist crimes to elite organizations like the SS, rather than considering the possibility that ordinary Germans may have been involved. According to the theologian and politician Wolfgang Ullmann, in the western part of the country, the belief was that antisemitic crimes had been committed in the name of Germans rather than by them. By blaming the Holocaust on specific elite organizations, it was possible to suggest that antisemitism was not a widespread issue and to absolve Germans of responsibility. However, the Auschwitz trials in Frankfurt in the early sixties created waves of interest, as did the showing of Schindler’s List in 1994.45

In 1995 the Hamburg Institute for Social Research launched a review of the twentieth century’s history, which was characterized by unparalleled devastation. The project aimed to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War II and provide insight into this tumultuous era. The project’s exhibition was successful, particularly in generating controversy and sparking debates, not only in Germany but in other countries as well. The researchers chose to focus on the Wehrmacht, the Reich’s largest military organization, believing that the theme would provide valuable insight into the functioning of NS Germany and its violent regime.

Apart from the exhibition, the project leaders organized lectures, conferences, and discussions that were aimed to present the history of violence to a wide audience. The exhibition focused on the involvement of the Wehrmacht in acts of mass murder in Eastern Europe that did not comply to the more traditional form of warfare. Within a couple of years, nearly one million people had visited the exhibition in thirty-two cities throughout Germany and Austria, generating both approval and controversy. Center-left parties supported and organized the exhibition, while center-right parties generally opposed it. In 1997, when the exhibition was shown in Munich, the extreme right-wing staged vehement protests that were countered by anti-neo-Nazi demonstrations implemented by left-leaning groups.46

Remembrance and Education

The year 1995 was also highlighted by ceremonies to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the NS regime. German political leaders, along with thousands of participants, traveled to former National Socialist concentration camps, in both the east and west of Germany, to recall the crimes of the Third Reich and to speak out for human rights in the present.47 Since 1996, January 27 has been recognized as a nationwide, legally established day of remembrance in Germany. The choice of date marks the day on which the Auschwitz extermination camp and the two adjoining Auschwitz concentration camps were liberated by the Red Army in the last year of World War II. Flags of mourning are hoisted on public buildings on this day and many events, such as readings, theater performances, and church services promote the memory of the crimes of the National Socialists. The day of remembrance also serves to draw attention to current trends of antisemitism, xenophobia, and misanthropy.

Education in Germany about National Socialism and the Holocaust has long been well established. All German states provide comprehensive coverage of these topics in either history or social sciences classes, and they are mandatory subjects in the eighth, ninth, or tenth school years. Additionally, the German education board encourages schools to arrange visits to places of remembrance or education, such as concentration camps or interpretive centers, in Germany or other countries.48

In the 1960s, former concentration camp sites in West Germany were opened to the public as places of remembrance and education. Over time, their educational offerings have expanded significantly, drawing an increasing number of German and international visitors, including many school groups. For example, the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site receives nearly one million visitors annually, with one-third of them being student groups.49

Since the early 1990s, Berlin’s Topography of Terror exhibitions have shed light on the crimes committed in Germany and throughout Europe by the Gestapo and the other various branches of the SS, as well as by the police. The Topography of Terror also administrates the former Tempelhof Airport site and Berlin-Schöneweide’s Dokumentationszentrum NS-Zwangsarbeit (National Socialist Forced Labor Documentation Center).

In 1999 the Dokumentation Obersalzberg center was opened in Berchtesgaden as a place of learning and remembrance relating to the history of Obersalzberg and the National Socialist dictatorship. In addition, the center presents a broader picture of the entire period, from the troubles of the post–World War I Weimar Republic through to the end of World War II. It offers a wealth of material and insights related to National Socialist ideology, propaganda, war crimes, and the Holocaust. The center conducts tours for a wide range of visitors, in particular to German school groups, Germany’s adult population, and members of the German armed forces. The annual number of visitors to this well-structured didactic center is between 145,000 and 170,000.50

The Institute of Contemporary History, originally called the German Institute of the History of the National Socialist Era, was established in 1949 following a suggestion by the Allied forces, with the goal of analyzing contemporary German history. The Obersalzberg center, located near Hitler’s former home and headquarters and below his Eagle’s Nest, was the institute’s pioneering initiative. The institute is funded by the German federal government as well as several states.

In 2001 a documentation center with similar educational goals as that of Obersalzberg opened its doors at Nuremberg’s former party rally grounds. Also, adjacent to Nuremberg’s Courtroom 600, where the world-famous 1946 Nuremberg Trials took place and which is open to the public, another informative interpretive center invites visitors not only to understand the historic importance of the legal proceedings against the National Socialist perpetrators but to see the broader picture of their regime of terror.

The Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism, established in 2015, serves as a facility for education and remembrance. It documents and addresses the crimes of the National Socialist dictatorship and their origins, manifestations, and contemporary consequences. The permanent exhibition explores the history of National Socialism in Munich, the city’s role in the terror apparatus, and its efforts to confront its past after 1945. The center’s educational concept and exhibition are founded on the principle of acknowledging, learning about, and comprehending the history of this location. The Documentation Center prompts visitors with two key questions: What does this have to do with me? And why should this still concern me today?51

The centers cited above are just a few examples of many. Several more worthy of mention include the former Order Castle Vogelsang IP, which provides excellent education about the SS organization; Wewelsburg Castle’s informative coverage of the SS organization; the Berlin Story Bunker’s “How Did Hitler Happen?”; and the many concentration camp memorial sites throughout Germany.

These numerous sites play a crucial role in edifying young Germans as well as those who may not have had the opportunity to learn about the history of the National Socialist regime and its catastrophic impact on Germany and the world. The comprehensive information available in English at these centers and memorial sites enables visitors from all over the world to gain a deeper understanding of the various aspects of these historical themes.

At all these centers in Germany and Austria the informative and educational content is presented in both an honest and unflinching way in its depiction of the grievous history of the National Socialist regime. Both Germany and Austria have made a concerted effort to confront their past and ensure that future generations understand the atrocities that were committed, both in Germany and abroad. Today, Germans are actively working to come to terms with the misguidance and crimes of their forefathers, and the country is emerging as a leader in the fight for racial equality and humanitarian policies.

The didactic content offered at these sites is a powerful reminder of the horrors that occurred before and during World War II and is a testament to the strength and resilience of the German people. By refusing to whitewash or rewrite history, Germans have shown a deep commitment to learning from the past and working toward a fairer future. As a result, the long years of finger-pointing at Germany are hopefully a thing of the past, and instead, mankind can focus on learning from this terrifying and sobering history.

By preserving the sordid memories of the Third Reich’s dictatorial regime, Germany’s history serves as an ongoing reminder and a dire warning to future generations. It admonishes us to sidestep the dangers of fascism and extremism, to remain aware of the devastating consequences of racism and bigotry, and to ever remember the importance of standing up for what we consider to be morally right, even in the face of overwhelming opposition. By continuing to learn from the past, humankind can help shape a more humane and more equitable future for all.

Notes

1. Brandon Tensley, “Why Are Former East Germans Responsible for So Much Xenophobic Violence?,” Washington Post, October 2, 2015.

2. Michal Kopecek, Past in the Making: Historical Revisionism in Central Europe after 1989 (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2008), 59–71.

3. Alliierten Museum, “Denazification,” https://www.alliiertenmuseum.de/en/thema/denazification/.

4. Norbert Frei, permanent exhibit, Topography of Terror Documentation Centre, Berlin, December 7, 2020.

5. Alliierten Museum, “Denazification.”

6. Permanent exhibit, Topography of Terror Documentation Centre, Berlin, December 7, 2020.

7. Morris Janowitz, “German Reactions to Nazi Atrocities,” American Journal of Sociology 52, no. 2 (September 1946): 141–46.

8. Harold Marcuse, Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933–2001 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 61.

9. Ibid.

10. Frederick Taylor, Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany (New York: Bloomsbury, 2011), 119–23.

11. Ibid., 97–98.

12. James L. Payne, “Did the United States Create Democracy in Germany?,” Independent Review 11, no. 2 (Fall 2006): 209–21.

13. Permanent exhibit, Topography of Terror Documentation Centre, Berlin, December 7, 2020.

14. Jeffrey Herf, Divided Memory: The Nazi Past in Two Germanys (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 380.

15. Gellately, Hitler’s True Believers, 318–19.

16. Herf, Divided Memory, 335.

17. Ibid., 381.

18. Bill Niven, Facing the Nazi Past: United Germany and the Legacy of the Third Reich (London: Routledge, 2002), 41.

19. Tensley, “Why Are Former East Germans Responsible?”

20. Niven, Facing the Nazi Past, 22–23.

21. Tensley, “Why Are Former East Germans Responsible?”

22. Ibid.

23. Barbara Dietz, “German and Jewish Migration from the Former Soviet Union to Germany: Background, Trends and Implications,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 26, no. 4 (2000): 635–52.

24. Sekou Keita and Helen Dempster, “Five Years Later, One Million Refugees Are Thriving in Germany,” Center for Global Development, December 4, 2020, https://www.cgdev.org/blog/five-years-later-one-million-refugees-are-thriving-germany.

25. Victoria Rietig and Andreas Müller, “The New Reality: Germany Adapts to Its Role as a Major Migrant Magnet,” Migration Policy Institute, August 31, 2016, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/new-reality-germany-adapts-its-role-major-migrant-magnet.

26. Michael Brenner, “In the Shadow of the Holocaust: The Changing Image of German Jewry after 1945,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, January 31, 2008.

27. “Jüdische Einwanderung nach Deutschland nach 1989,” Lernen aus der Geschichte, March 15, 2016, http://lernen-aus-der-geschichte.de/Online-Lernen/Online-Modul/9136.

28. World Jewish Congress, “Germany,” https://www.worldjewishcongress.org/en/about/communities/de.

29. Berman Jewish DataBank, “2020 World Jewish Population,” https://www.jewishdatabank.org/databank/search-results?search=World+Jewish+Population.

30. Federal Ministry of the Interior and Community, “Strengthening the Jewish Community in Germany,” July 6, 2018, https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/kurzmeldungen/EN/2018/07/zentralrat-der-juden.html.

31. Tensley, “Why Are Former East Germans Responsible?”

32. Kopecek, Past in the Making, 59–71.

33. Frank Decker, “Wahlergebnisse und Wählerschaft der AfD,” Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, December 2, 2022, https://www.bpb.de/themen/parteien/parteien-in-deutschland/afd/273131/wahlergebnisse-und-waehlerschaft-der-afd/.

34. “German Court Rules Far-Right AfD Party a Suspected Threat to Democracy,” Guardian, March 8, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/08/german-court-rules-far-right-afd-party-a-suspected-threat-to-democracy.

35. Emily Schultheis, “East Germany Is Still a Country of Its Own,” Foreign Policy, July 7, 2021.

36. Armin Pfahl-Traughber, “Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung,” Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung, June 17, 2019, https://www.bpb.de/themen/rechtsextremismus/entgrenzter-rechtsextremismus-2015/202684/armin-pfahl-traughber-die-besonderheiten-des-nsu-rechtsterrorismus-im-internationalen-kontext/.

37. Zeit Online, February 8, 2021.

38. Kopecek, Past in the Making, 59–71.

39. Herf, Divided Memory, 384–85.

40. Ibid., 3.

41. E. Dresler-Hawke and J. H. Liu, “Collective Shame and the Positioning of German National Identity,” Psicología Política 32 (2006): 131–53.

42. Christoph Hasselbach, “Holocaust Remembrance in Germany: A Changing Culture,” Deutsche Welle, January 27, 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/holocaust-remembrance-in-germany-a-changing-culture/a-47203540.

43. Dresler-Hawke and Liu, “Collective Shame.”

44. Ibid.

45. Niven, Facing the Nazi Past, 137.

46. Ibid., 143–44.

47. Herf, Divided Memory, 367.

48. Deutscher Bundestag, “Die Verankerung des Themas Nationalsozialismus im Schulunterricht in Deutschland, Österreich, Polen und Frankreich,” September 18, 2018, https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/577838/057659f45ba3ae2fc1ba10aca4f1da91/WD-8-091-18-pdf-data.pdf.

49. “Jeder Schüler soll ein ehemaliges KZ besuchen,” Süeddeutshe Zeitung, June 7, 2018, https://www.sueddeutsche.de/bayern/gesetzentwurf-jeder-schueler-soll-ein-ehemaliges-kz-besuchen-1.4004537.

50. Sven Keller, Albert A. Feiber, and Eva-Maria Zembsch, Dokumentation Obersalzberg, Jahresbericht 2018 (Munich: Institut für Zeitgeschichte, 2019), 6.

51. NSDOKU Munich, “About Us,” https://www.nsdoku.de/en/about-us/the-nsdoku.