Now more than ever, young people are realizing that the future is theirs to create, not something that will simply happen to them.

—Stacy Ferreira and Jared Kleinhart, 2 Billion Under 201

Evan began reviewing toys on his YouTube channel called EvanTube when he was five. At 9 years old, he now has more than 2.8 million subscribers and rakes in a cool $1.3 million annually for his work.2 Seven-year-old Alina Morse wanted a lollipop that didn’t cause tooth decay. After speaking with her dentist, she invented Zollipops using $7,500 in money given to her by her grandparents, which became the only candy served at the White House on Easter in 2016. Sales have been up 378 percent year on year and she is now 10 years old.3 Moziah Bridges started a bow tie company when he was 9 and became the youngest entrepreneur to participate on Shark Tank. In 2015, he earned $250,000 in revenue and the business continues to grow.4

When Evan, Alina, or Moziah turns 22, will traditional companies have what it takes to attract and retain them? The expectations of someone who has run a business since the age of 9 are vastly different than the simple college graduate of yesteryear. While other generations also had youthful entrepreneurs, the barriers to starting a business have greatly decreased with the rise of digital technology. Entrepreneurship is not necessarily defined as a full-time pursuit. In the millennial and especially gen Z generations, there are many with so-called “side hustles,” some type of profit-making venture outside of their full-time job. Even without being involved in any kind of venture, millennials and gen Z exercise entrepreneurial spirit through the questions they often ask in their 9 to 5 jobs, in a continual drive to make the most of their self-perceived potential. What expectations of work have emerged because of our ability to be more entrepreneurial in our youth? How are those expectations perceived by those who are already in the workforce?

For this particular stereotype, the observable behavior is that millennials have different expectations for opportunities to contribute to and rewards to gain from the organization. From a traditional perspective, this can be perceived as entitled because modern talent has expectations of rewards and career growth that are different than before—when in the past, simply having a job with a regular paycheck was reason to be grateful. From a modern, top talent perspective, growing up has inherently involved entrepreneurial spirit and the idea of pursuing one’s full potential, leading to workplace expectations that are most closely represented in start-up or entrepreneurial environments. In addition, modern talent is deeply aware that having a traditional job is only one of many options to gain a sufficient living in today’s world. Table 3.1 summarizes the observable behavior, the two sides, and the supporting beliefs.

From a traditional perspective, entitlement sounds like this in the following scenarios:

› Promotion-related: “I’ve just started and I’m wondering when I will get a promotion” or “I’ve been here for six months and I think I’m ready for the next level.”

Table 3.1 One Coin, Two Sides model for entitled vs. entrepreneurial interpretations of modern behavior.

One Coin: One Observable Behavior Different expectations for opportunities to contribute and rewards to gain. |

|

|---|---|

Side 1: Traditional Interpretation Entitled |

Side 2: Top Talent, Millennial-Based Modern Interpretation Entrepreneurial spirit |

Supporting Beliefs: › You should just be happy to have a job. A job is something that is given to you, and not everyone has the opportunity to have one. › A job, at its bare minimum, is a way to earn a paycheck. I want my job to be fulfilling too, but first and foremost, I need to pay the bills. › You should put in the time before asking for any rewards. You need to demonstrate that you are worthy before even asking. Why would the company give you something when you’ve done nothing yet? › There is no difference today in the breadth of skills, knowledge, and experience of new hires or type of work we are tasked to do. Therefore, they still need to put in the time and “grunt work” before moving to strategic work. › I feel threatened. Millennials ask for a lot of challenge and even if, by chance, they are ready for it, there’s not enough room at the top for all of us. We can’t all be senior-level employees. If there are too many people who have significant work responsibilities, I may be out of a job. |

Supporting Beliefs: › I will take jobs with lower pay because I am after experiences that grow me and a life that is fulfilling. I’m not as interested in materialistic things as older generations, because it’s been said since I was a kid that money doesn’t make you happy. I believe in YOLO, and if I only live once, why would I want to work for you? I need a good reason. › Jobs are only one way to earn income. Having a job is not having a special privilege. In fact, seeing how companies demonstrated in my formative years that they do not care about their employees, having a job is somewhat of a misfortune compared to other options today. › I have been contributing my voice and skills since a young age through the Internet. I don’t want to go backwards in my journey of self-development. When I can bring my full breadth of skills to work, I’m more engaged and willing to help the business grow their vision. |

Source: Invati Consulting

› Recruiting: Attempting to negotiate better salary and benefits during the recruiting process.

› Work plan: Asking for more challenging work or showing poor performance when doing routine tasks.

› Flexible hours: Asking for flexible hours or simply not showing up when expected.

› Skirting hierarchy: “Hi, you’re my VP right? I just wanted to introduce myself and maybe we could get lunch some time?”

› The big picture: “Why are we doing it this way?” or “How does this connect with the mission?” or “The strategy doesn’t make sense to me.” Wanting to provide input at a higher level or during a strategic conversation.

Consider Diane, an old high school classmate of mine. At age 15, she started showing up at university laboratories asking for a job. She had no experience. She had no education worthy of such a position; she wasn’t even out of high school. Yet there she was asking. And asking for nine dollars an hour. Sound entitled? We will return to Diane’s story to explore further.

The definition of entitlement is the belief that one is inherently deserving of privileges or special treatment. What was considered a privilege from a traditional perspective? Older individuals may believe that, at a young age, one should be happy just to have a job, and asking for more than that is asking for a privilege. For example, Dave, a boomer VP of regional sales, says, “In my day, we didn’t know how much we were getting paid until we got the job and the first paycheck in the bank. We were told not to ask . . . by our mothers!” In the traditional workplace, things like salary, flexible hours, graduating from grunt work, and meetings with more important people were rewards. They were things you didn’t ask for until you had proven value to the company. It was uncommon enough for a new person to challenge why things were done a certain way that it became a sign of a high-potential, future leader. From this vantage point, it’s no surprise that when millennials ask, or worse, assume that these “rewards” are a part of the job, they are perceived as entitled.

In addition, recall that older generations grew up in a greater command and control, hierarchical world. The technology that controlled information at the time (radio, television, and print) was a very one-way interaction and had limited transparency. Older generations didn’t know how much everyone around them was getting paid or what benefits they had. With less knowledge, there is less reason to ask such questions and hence previous generations were more accustomed (not necessarily happy about it!) to a small handful of people at the top, controlling destinies at the bottom.

What about workplace readiness after college? What messages about career choices were given to older generations when in school? Throughout the past 50 years, safety mindset, work experience, desegregation, and equality have changed enormously. Boomers and gen Xers spent much of their time after school free to roam around until dinner, with no concerns about safety. Life wasn’t scheduled or monitored outside of school. Teenage jobs included babysitting, mowing lawns, and dog walking. College internships were often involved no more than making copies, answering phones, taking meeting notes, and bringing coffee. Observing others work was where the education happened.

In the 1960s, after the passing of the Civil Rights Act, the public education system started the process of desegregation, in which schools were no longer allowed to be built specifically for blacks or whites. This process continued into the 1970s, with challenges such as Hispanic/Latino desegregation and continued resistance from some Caucasian communities.5 This struggle for equality extended into the workplace. If you were of another race or if you were a woman, career prospects were different. As a woman, you could have the exact same job as a man and be paid far less. There was a broader belief that careers were gender-specific. This clash is humorously brought to life in the popular 2000 movie Meet The Parents, where a young man in his twenties, played by Ben Stiller, is constantly teased and looked down upon by his girlfriend’s father, played by Robert De Niro, for being a nurse. The traditional mindset was that men are doctors, women are nurses. In general, career options were relatively fewer for everyone in comparison to today. Common career paths included accounting, teaching, medicine, engineering, law, nursing, journalism, and agriculture, to name a few.

Education practices evolved as well. When in school, previous generations were exposed to different topics and teaching styles: a focus on textbook-based learning instead of active application or group projects; courses like Home Economics instead of Robotics and Programming; and memorizing and listening to the “sage on the stage” instead of asking and contributing. As a result, in many workplaces, the traditional mindset meant that the ramp-up to strategic roles was a slow, arduous process that reflected the assumption that youth lack workplace skills and knowledge. Higher levels of work also involved having higher experience in diverse, team-based situations. Since many kids hadn’t grown up traveling or in diverse, team-based environments, these were additional items to be learned on the job. Corporate career path models and individual goal setting processes reflect this outdated reality.

Another common assumption is that entitlement is caused by all millennials experiencing a much kinder parenting style and receiving awards as part of being the “trophy generation.” I argue that there is much more to the story. As mentioned in chapter 1, the highly diverse millennial generation grew up under a variety of parenting styles. Yet many millennials, regardless of background, have greater expectations that are perceived as entitled. That implies there are other, more comprehensive reasons to explain millennial behavior. What do millennials and gen Z perceive as rewards and goals today, given the advances society has made?

Let’s return to Diane’s story, my high school classmate who strolled up to universities asking for a job with no credentials. What if I told you that today Diane is a graduate of Rice University and Harvard Medical School and is pursuing her residency in pediatric neurology? Still sure that she was entitled? When viewing her actions without context, as many of the individuals she approached may have done, she may appear entitled and wanting to be handed something for nothing. In retrospect, even in her own words, “It sounded utterly clueless. After all, many in the scientific community believe that ‘talent’ alone is the most important ingredient for a successful scientific career.”6

What made her actions different from entitlement? It was the sheer perseverance of it all. She had been given advice that the way to get the job was to talk to the boss. She e-mailed 40 principal investigators, asking for a summer position. She also let them know that if they didn’t reply, she’d be visiting their office in person and included a specific date and time. While many kindly replied with a polite decline, 10 people didn’t respond. She dressed her best and visited the 10 people as promised. She received three offers. The first two were unpaid; the last offered her $8 and she asked for $9. She got the summer internship—and followed through with hard work!

We often judge actions instantly, without knowing the complete story. What may have sounded like another millennial being entitled was actually something quite different. As Diane has gotten older, she has realized that there is a distinction between being entitled and advocating for yourself. While many people may confuse the two, she’s found that self-advocacy is just as important as innate talent. Self-advocacy is rooted in understanding and pursuing one’s full potential, passion, and purpose.

And that is what’s driving youth today—potential, passion, and purpose over a paycheck. Did you know that 72 percent of high school students want to start a business some day and 61 percent would rather be entrepreneurs instead of employees right when they graduate college?7 Albeit, many high school students aren’t aware of or deemphasize the hardships of entrepreneurship. Nonetheless, entrepreneurship is attractive because the desired rewards from work have changed for modern talent, from just collecting a paycheck to living life to the fullest. Because the idea of rewards and privilege has shifted, the questions and expectations of millennials have shifted as well. What I’ve found is that this shift is not about being entitled, it is about having an entrepreneurial spirit and passion for life fulfillment—and often, not being beholden to a sinking ship.

Growing up during the Great Recession, watching parents who spent their lives working for companies only to see their retirements disappear along with a reduction in benefits, has greatly disheartened millennials and distanced them from the traditional corporate track. Consider the example of the pension plan—an all but forgotten relic in today’s world that honored employees’ long service. Whereas many boomers may have woken up in their forties with a midlife crisis from lack of meaning in their life, millennials often feel having a quarter-life crisis is a better alternative. Having witnessed and heard since a young age that “money doesn’t buy happiness,” “you can do anything you want to do,” and “follow your passion” with a wide variety of career paths available to them, millennials have taken the message to heart and are exploring a variety of ways to make this happen.

In the past, distrust in companies didn’t stop people from taking jobs because there really wasn’t a viable alternative. A newly formed belief is that because of technology, millennials and especially gen Z have many more options outside of a traditional 9 to 5 to make a living. Having a job is not seen as having a privilege in itself; remarkably, today it is seen as a disadvantage. In fact, those that make a living outside of “the system” are the ones who are idolized and respected by other millennials. What is so great about having a job that one should be grateful? We are all driven by the potential pains and pleasures we perceive. Boiling it down to a simple philosophy, with so many choices available to them, I’ve found that millennials live their lives according to the idea of YOLO—you only live once—which describes the reasoning behind the fulfillment-oriented rewards they pursue. Conversely, they are driven by a pain, too, due to all the choices: FOMO, or fear of missing out.

Organizations don’t often realize that young people today consider traditional 9 to 5 companies to be just as risky as start-ups and entrepreneurial ventures. If you have to choose between working for a company where you will grow slowly and simply make a salary before they lay you off versus working for a start-up where you will learn a lot and it could go public or it could go bust, most younger people are inclined to choose the latter. Working for the paycheck? Why? They are only going to treat me like a number, reduce my benefits, and eventually lay me off. If I’m going to work 50+ hours a week, why not do it for a start-up or for my own venture where I can make a greater contribution, gain transferable skills fast, and potentially reap a greater reward? This avenue of thinking meets the need for YOLO and FOMO—emphasizing that a job by itself is not something to be grateful for that will make the most of life. In the long run, it leads to a new set of questions that ask companies to prove the value for employees’ time and effort.

A second driver behind these questions is that the start-up and freelance mentality enables modern talent to use the skills they have been using their whole lives. Millennials have grown up with a significantly reduced barrier to starting businesses and having a voice. When once the adage was “children should be seen and not heard,” today’s world is couched in the anonymity and reach of the Internet. Consider how technology has created entrepreneurial spirit by allowing individuals to:

› Reach a target or extremely niche market

› Develop a following and be respected regardless of age

› Learn skills and gain knowledge rapidly

› Have ownership and create strategy

› Generate revenue with little to no start-up capital

Millennials and especially gen Z have more exposure to what it means to “be in charge” and be a part of a start-up atmosphere than previous generations, through experimenting with businesses at young ages. Contrary to outdated expectations, the new hire that just joined your company has probably done more than make copies and bring coffee during their internships, work experience, and course of study. While not familiar with every aspect of running a business, the new hire has probably been exposed to a customer-focused business mindset since grade school—a world of user experience, “likes,” social media following, copy writing, managing image, communication, and influence. They’ve been exposed to incredible diversity and the global nature of the world, if not through traveling, then through the Internet. Joining a workplace means bringing those skills to work every day; they can’t be turned off or compartmentalized to personal hours only. And why should they be?

Balancing YOLO and FOMO is about collecting experiences first, material goods later (or not at all). The rise in tiny homes, ride sharing through companies like Uber and Lyft, home sharing through companies like Airbnb and Couchsurfing, and even group living situations exemplify the emphasis on not spending significant money on owning material goods. Instead, millennials travel the world, go on adventures, purchase experiences at lowered costs through sites like Groupon. This mindset translates to the work world as well, with those questions around challenging work, strategic thinking, building relationships with leaders, flexible work arrangements, and so on. However, this pursuit and expectation for experience doesn’t mean that millennials aren’t putting work in. In fact, for top talent millennials, it means the opposite! They ask because they have experience they want to bring to the table now, not wasting an organization’s time or their own when they could be making significant contributions.

Consider the story of Jonathan Barzel. In the five years since finishing his undergraduate degree, Jonathan has lived in four different cities in two countries and worked in three different industries. After graduating from the University of Memphis with his bachelor of science in mechanical engineering, he traveled to Sydney, Australia, where he lived and worked for the next two years as a sustainability consultant. He transitioned back to the US in the same industry, but pivoted for an opportunity to join a data analytics platform start-up in a business development role. Through this role and his philanthropic involvement in his city’s start-up community, he took the exciting opportunity to join a Fortune 50 package and delivery company on their financial planning team. This group typically focuses on hiring post-MBA candidates who then help shape the strategy and direction of the company at the highest levels.

Jonathan did not act from an entitled “I deserve these experiences” standpoint at any time. He was driven by his entrepreneurial spirit, his desire to make the most of his potential and live a fulfilling life. Part of what enabled him to get global and start-up experience at such a young age was the infrastructure offered by digital technology, including the greater ease of relocation, the ability to find jobs, and the ability to grow his own knowledge about each situation. In his words, the common themes in all of these jobs have been threefold: a drive to have an impact—on those around him, on product and service quality, and on each business financially; a hunger for constant personal and professional growth and learning; and an emphasis on forming meaningful connections with his customers and colleagues. These themes define what YOLO means to Jonathan. Again, this was all in the five years since graduating—he certainly isn’t missing out on life’s experiences!

To summarize, this side of the coin is about breaking the paradigm that jobs are given and jobs are taken, that our work lives are somehow out of our control. While we all need to make a living to survive, millennials and especially gen Z are more willing to experiment with how to gain that living. They would rather fail at their own hands than fail to make money because a company took their job away. Same time and effort, different experience. In addition, top talent is coming to the table with increased business acumen and skill sets. They expect to change the obsession with age and tenure and instead focus on the skills brought to the table and tap into their potential from day one.

So when millennials ask for challenging work or to be promoted earlier, it’s not about entitlement. It’s about wanting to make the same kind of contributions millennials and gen Z are already used to making personally in a professional environment. When they ask questions about salary and benefits, that’s because they perceive getting a job just as transactionally as companies view their employees.

Using the One Coin, Two Sides model, we now understand the changing ideas of reward and fulfillment that are occurring. This increased level of knowledge, experience, and expectations is not going away, because digital is not going away. While the traditional interpretation for gratitude is not right or wrong, the conditions of society today have brought forth a different attitude toward jobs. Modern talent, as a whole, will continue to assume the base transactional details will be present and for the real conversation to be about maximizing the win for both company and employee. Companies that transparently answer the “entitled” questions up front and then focus on capturing the entrepreneurial spirit of modern talent will be the ones to succeed and thrive.

Entrepreneurship is attractive to young people because of all the things they perceive they can get that they can’t get from a company, especially the digitally enabled idea of bringing their full selves to everything they do and of living by the philosophy of YOLO. In the entrepreneurial environment, this looks like having the ability to:

› Work in a fun culture

› Be part of a fast-paced environment

› Wear multiple hats

› Have a lot of responsibility and autonomy fast

› Work on something that matters (to society and to themselves personally)

› Always see the big picture

› Be part of a goal-focused culture that is highly productive (in the modern terms we described in chapter 2)

› Always see the results of the work put in

› Potentially make a lot of money

From a traditional interpretation, where there were fewer options for careers, these were seen as privileges to have, and therefore a perception of young people being entitled has evolved. Instead, the key intervention is to move from naming the behavior as entitled to harnessing entrepreneurial spirit by cultivating an “intrapreneurial” culture.

First, we must understand what entrepreneurship means to young people. Older generations think about entrepreneurship as starting a “real” business—maybe a brick and mortar store or a venture that will require investment and one day could be bought by another company. Young people think of entrepreneurship as everything and anything that can support them financially. And, with the delay in marriage, often it’s enough to support themselves. This could include freelancing, working from home at online jobs, e-commerce, or a combination of these. A study done by Millennial Branding and oDesk highlights that 90 percent of millennials believe that being an entrepreneur is about the mindset; only 10 percent believe it is about having actually started a company.8 Most people aren’t attracted to entrepreneurship because it’s easy but because they want to escape the perceived pain of corporate culture.

Many millennials may never start a venture, full-time or on the side. There is a distinction I’d like to draw between entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial spirit. Not all millennials are entrepreneurs, but many have entrepreneurial spirit. Some essential components of entrepreneurial spirit are a deep commitment to doing something of significance, having a zest for life, and not being able to tell the difference between work and play. Entrepreneurial spirit is about pursuing your own passions and potential to the fullest. It is a highly motivated, purpose-driven state of being.

How can we transform corporate culture to leverage entrepreneurial spirit? Building an intrapreneurial culture encompasses both issues: it inherently addresses many of the growth-related questions that appear as entitlement and it harnesses the entrepreneurial spirit. The traditional concept of an intrapreneurial culture involves selecting a few employees who seem entrepreneurial to receive seed funding and try out an idea, as a reward. For example, a traditional approach is to keep an eye out for talent that questions fundamental approaches, takes initiative to suggest improvements, and in general acts like a future leader. Then, projects may be assigned outside of the daily tasks of the role. In this situation, the organization waits for ideas based on pure individual motivation and hopes managers notice. Another common approach is to hold an internal competition within a particular function, such as engineering or R&D, once a year to generate and collect the best ideas. Participation is generally unsupported, reliant on personal motivation, and an independent action. In contrast with these approaches, to engage modern talent, shift from intrapreneurship as a reward and an individual activity to intrapreneurship as a part of every role and the community.

In today’s highly cognitive world, there is room for innovation, creativity, and learning in almost every role. This is something corporations need, even if they don’t know it or want it. Some of the top qualities the C-suite say they are lacking in their leadership pipeline are things like agility, ability to deal with ambiguity, cross-functional team leadership, and innovative thinking. Many of these qualities are a part of an entrepreneur’s DNA! In my research, the number one statement millennials find demotivating is “it’s always been done this way.” Instead, the first step to embrace entrepreneurial spirit and pursuit of fulfillment is to stop labeling it as entitlement.

One place where the rewards of this approach are evident is when millennials become managers and promote open idea sharing. Sherina Edwards is the youngest commissioner ever appointed at the Illinois Commerce Commission. Her management style is focused on an open group policy, where anyone can voice an idea and it is encouraged to think bigger than one’s role. As an example, Edwards asked an executive assistant to think bigger than her role. The employee highlighted a gap—the commission had an awareness problem where the people of Illinois didn’t know what the commission did. The employee suggested creating a one pager for customers. Edwards sent the created document to the whole organization, recognized the employee who conceived it, and ensured it was used. The employee said no one had ever done something like that, especially for someone in an administrative role. Edwards made sure to create an environment where everyone could exercise entrepreneurial spirit and received an idea that improved the brand awareness of the commission as a result. Especially in the public sector, those with a traditional mindset don’t often see the value of this approach.

One of the simplest ways to build an intrapreneurial culture is to allow a portion of employee work plans to be free. The range of free time could be anywhere from 5 to 20 percent. Another possibility is providing a way to capture innovations. One way to do so is to ensure that managers stay in touch with free time spent and proactively collect feedback. This tactic is most useful when manager-employee relationships are strong. Sometimes, however, talent that is considering leaving may have a tenuous relationship with their manager, and having another way to appreciate their contributions can help reengage. Having an online social network or repository can be a great way to capture, discuss, and assess ideas. Often, the best ideas are overlooked, but it just takes one person to sponsor one.

Another important element of building intrapreneurship is to allow everyone to feel like an owner of the company. Every employee must feel like an owner of their role. In an intrapreneurial environment, the work plan is a discussion and open to input by the employee. Every employee also has a clear idea of the strategic vision of the company and how their role contributes. Even though they may not hold stock, like senior leaders do, if they know how their role impacts profits, they are more incentivized to contribute.

Anne Moder was one of the best managers I had, because she allowed me to feel like the owner of my role and my career. As I mentioned earlier, I made a career transition from engineering to training, but that move didn’t happen overnight! Over three years, I had the opportunity to explore my career interests through one-on-one meetings with Anne where I constantly asked for more projects, more mentors, and planned out career moves way too early. (The folly of youth is thinking that you can plan 10 years ahead!) Anne could have approached our relationship with a feeling that I was being entitled asking for more, more, and even more, but she didn’t. She approached me from the standpoint of being a sounding board, a collaborative partner, and we put projects on my work plan to reflect my needs for exploration. These projects included everything from engineering work to organizational culture work, such as leading the new hire network. They involved trying out new ideas as well. These experiences allowed me to gain significant clues about harnessing my purpose and potential. From a business standpoint, the support of my manager allowed me to focus on my projects instead of resenting them, stay engaged and remain at the company instead of looking for ways out, and exceed my role’s goals instead of doing the bare minimum. Would it have been easier to discourage me than to collaborate and sort through the situations? I’m sure it would have, but I’m also sure there would have been a significant impact to my work.

In a successful intrapreneurial culture, employees don’t feel as insecure about being promoted, gaining benefits, or gaining access to senior leaders, because they have the security that their ideas are valued, that they are allowed to have experiences outside their direct line of work, and that they can work effectively within the larger vision of the company. Consider answering many of these basic questions about salary, benefits, and career path up front during the recruiting process and while on-boarding. Then see what talent does with that information. Does the individual rise to the challenge, or do they prefer their existing role?

The importance of harnessing millennials’ entrepreneurial spirit and leveraging their potential cannot be understated. With boomer retirements looming, millennials will need accelerated leadership development. In many cases today, the challenge has already been reversed—junior talent is managing senior talent. Thirty percent of millennials are already in management positions.9 Dave, the VP of sales I mentioned earlier whose mother discouraged asking questions about salary, said it best when it comes to entitlement-perceived questions today: “If someone doesn’t ask today I think there’s a problem with that. That maybe they are insecure or desperate. So today, when someone doesn’t have high expectations, I’m more worried.”

There are many examples of traditional intrapreneurial programs, such as innovation labs, advisory boards, and internal subject matter expert communities. These programs, while certainly a great effort toward building an innovative culture, still fall short of capturing ideas across domestic or global scale and making innovation a part of daily work. Consider the following two concepts of intrapreneurial culture in action as you build your intrapreneurial culture.

These findings support the innate expectations of digitally enabled talent and go against the traditional approach to intrapreneurship. The idea of locating a few people who have shown entrepreneurial interest is not the way to harness innovation or engage the full potential of your workforce. Instead, making sure the collective whole has equal opportunities to interact, voice opinions, and build consensus is what sparks the most innovation. Online networks have a huge potential in helping to facilitate innovation. On the Internet, everyone enters as an equal. We can take turns, have brief conversations, and build consensus through upvoting ideas. Based on Pentland’s extensive research, I believe embracing digital is a great way to spur intrapreneurship and engage employees of all generations.

Instead of staying focused on keeping things the way they’ve always been done, Cisco is seeking to use today’s tools and ideas to capture the power of their global workforce in disruptive ways never before seen. Cisco is encouraging every employee to ask why, to be strategic, to be a business owner, because they see the benefit to the business, not only to create the next game changer for customers, but to make significant improvements to their everyday work processes.

In this chapter, we learned how the expectations of the capabilities one brings to the workplace differ between a traditional and a modern perspective. Millennials have a tendency to ask questions and put forth expectations that sound entitled from a traditional perspective, when one was simply grateful to have a job and to slowly grow skills over a lifetime. In today’s fast-paced, highly cognitive world where young people don’t have to get a traditional job and bring a different skill set, millennials have evolved different expectations of workplaces that leverage their innate entrepreneurial spirit, tied to the philosophy of YOLO. Digital technology has decreased barriers to starting a business and provided more information about options for making income, enabling greater entrepreneurial spirit. From the stories of Diane and Dave, we heard evolving views of entitlement and rewards. While the traditional perspective served well previously, today’s world has changed. To modernize the workplace, it’s imperative to develop an intrapreneurial culture—not just to attract and retain millennials and gen Z, but to develop all employees with the skills to remain profitable and thrive in a world where innovation is king.

In addition to redefining being entitled as having entrepreneurial spirit, we learned that the definition of intrapreneurship is changing. Where intrapreneurial culture was once reserved for an elite few employees, efforts today should seek to improve idea flow across the complete scale of the company. Through sharing stories of Jonathan Barzel’s five-year journey, Sherina Edwards’ “any role can contribute” philosophy, and Anne Moder’s guiding life-fulfillment management style, we heard some of the benefits of embracing an entrepreneurial versus an entitled mindset. From our research sharing, we saw how Alex Pentland’s work highlighted that it is the diversity of ideas and broad discussion of ideas that make up the foundation of an intrapreneurial culture. The example of Cisco shows the success of efforts that contain these modern intrapreneurship elements that harness the power of our digital networks. In summary, we learned that the power of the collective is unleashed when people are given time to explore ideas and places to share and rate such ideas.

By embracing the idea that it’s okay to ask questions and focus instead on the ideas that emerge, we engage, retain, and get high productivity from modern employees who seek to live a life of fulfillment and be entrepreneurial in their careers.

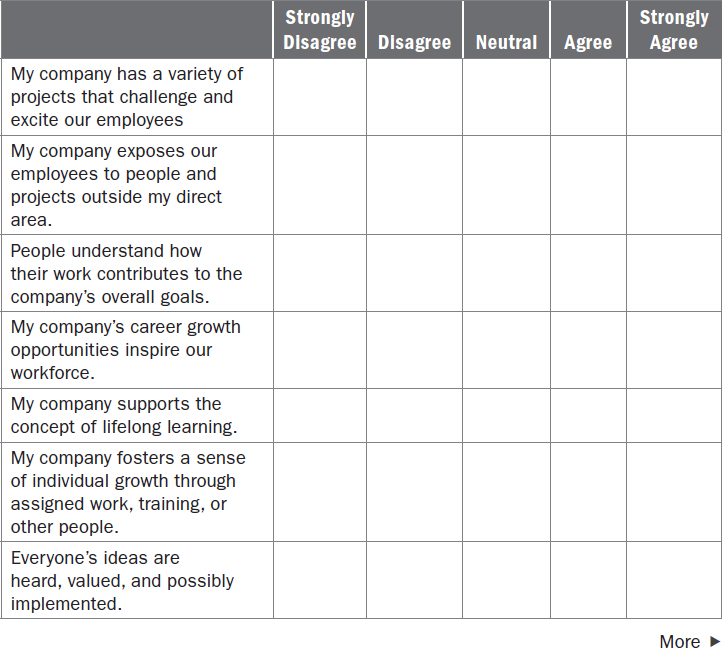

How well do you think your organization is meeting modern talent needs? Read each statement and place an X in the appropriate column, then sum up your score. We have stated “my company” for the focus of each statement, but feel free to replace with “my immediate work group” or another community if it serves your purpose better. The assessment can also be found online at themillennialmyth.com/resources, where you can compare your answers with other readers.

If the majority of your X’s fall in the strongly disagree or disagree columns, your organization is leaning toward a traditional perspective that is at risk of disengaging modern talent. You may want to see where you can make some changes through reviewing portions of this chapter, trying the 10-Minute Champion ideas below, investigating our online resources, or reaching out to us for further help.

What can you do to shift your organization toward a modern culture? Consider championing the following ideas in your work group, intended to take no more than 10 minutes each.

Facilitate idea generation. Close your meetings with open-ended idea-generating questions: Is there anything we could do to improve our existing process? Is there anything you would change?

Facilitate idea generation. Close your meetings with open-ended idea-generating questions: Is there anything we could do to improve our existing process? Is there anything you would change?

Facilitate cross-functional connections. Pick one person on your team. Consider their work. Are there any connections or resources outside of your team (or company) that would be helpful for them?

Facilitate cross-functional connections. Pick one person on your team. Consider their work. Are there any connections or resources outside of your team (or company) that would be helpful for them?

Provide insight. Bring one resource or insight that’s external to your group (could be from another function or from outside your company) that you think would be interesting. Send it in an e-mail to your team, post it on an internal social network, or talk about it during a group meeting or an informal time such as lunch.

Provide insight. Bring one resource or insight that’s external to your group (could be from another function or from outside your company) that you think would be interesting. Send it in an e-mail to your team, post it on an internal social network, or talk about it during a group meeting or an informal time such as lunch.

Step back and innovate. Pick a part of your job that you do regularly. Take a few minutes to ask yourself why the task is done or why the task is done the way it is. Note any inconsistencies or improvements that could be made.

Step back and innovate. Pick a part of your job that you do regularly. Take a few minutes to ask yourself why the task is done or why the task is done the way it is. Note any inconsistencies or improvements that could be made.

Create your own idea. Feel free to create your own idea to build an intrapreneurship culture.

Create your own idea. Feel free to create your own idea to build an intrapreneurship culture.