What we’re experiencing is, in a metaphorical sense, a reversal of the early trajectory of civilization: we are evolving from being cultivators of personal knowledge to being hunters and gatherers in the electronic data forest.

—Nicholas Carr, The Shallows1

With the relatively recent introduction of digital technology in our lives, we all are experiencing its consequences for the first time. In the previous chapters, I have shown how digital technology has influenced millennial behavior and expectations around where and when we work, as well as the type of work we do and the skills we use. In addition, it has also greatly impacted how we process and use information. As was also established in the previous chapters, older generations form a different conclusion from observed digital behavior than millennials and generation Z.

Picture a millennial starting a job. Within the first week, they ask for feedback. “How am I doing?” they wonder. They want weekly meetings to make sure their performance is on track and to ask for support as needed. As a result, they achieve their metrics. A gen Xer, on the other hand, uses these meetings to understand the assignment and simply says, “I’ll get it done.” The gen Xer finds the necessary resources and achieves the metrics set at the beginning of the project.

A year later, it’s performance review time. Which one is more likely to have high performance? Which is more likely to feel engaged? Which has the better relationship with their manager? It’s not easy to tell which approach is right or wrong. Both approaches may work equally well, given the preferences of the individuals involved, because we all process and use information differently.

How has the experience of moving from cultivators of knowledge to “hunters and gatherers in the electronic data forest” impacted the older perspective? How has spending most of their lives in the same electronic data forest changed the younger generations?

For this particular stereotype, the observable behavior is that millennials desire feedback. From a traditional perspective, used to cultivating knowledge, this can be perceived as needing to be held by the hand. From a modern, top talent perspective, gaining information quickly and frequently is the way to be agile in today’s hunter and gatherer world. Table 4.1 summarizes the observable behavior, the two sides, and the supporting beliefs.

When millennials ask for feedback and exhibit “needing to be hand-held” type behavior, it sounds like:

› Did I do a good job?

› Can you tell me how I’m doing?

› Can you help me make this better?

› Can you review this?

› How would you recommend I do this?

› Am I on track?

Table 4.1 One Coin, Two Sides model for needing to be hand-held vs. agile interpretations of modern behavior.

One Coin: One Observable Behavior Asking for feedback |

|

|---|---|

Side 1: Traditional Interpretation Require hand-holding |

Side 2: Top Talent, Millennial-Based Modern Interpretation Desire agility |

Supporting Beliefs: › The trophy generation wants praise for even the smallest things. I’m not going to give you an award just for showing up. › I shouldn’t have to give someone all the answers. It’s okay to help out once in a while, but ongoing, they should have the initiative to find it themselves. Someone who has to be given the answer isn’t a self-starter and probably doesn’t have the right capability for the job. › Cultivating deep knowledge and expertise takes time and is the best and/or only way to be successful. Some things you can only learn through experience. There isn’t really a better way to learn it. |

Supporting Beliefs: › Feedback is another form of learning and is not always related to performance. I can learn a lot and gain a lot more experience faster if I ask for feedback. It is the beginning of agile leadership. › The more meaningful feedback I have, the more I can adapt to situations in real time. › I am more likely to appreciate meaningful feedback than recognition for just showing up, which oftentimes feels inauthentic. › There isn’t value in working for the answer. Only make me work for the answer if there is value in me working for it. If the value is learning how to cut through red tape and bureaucracy, the feedback isn’t for me, but for the organization: figure out more efficient ways to get your people the info they need to actually do their jobs. |

Source: Invati Consulting

And it sounds like these statements . . . frequently. Like every other day. Given how much managers loathe the time and energy required for annual performance review processes, doing a quick performance review every other day seems absurd.

As mentioned in the previous chapter, when older generations were growing up, asking questions was not always encouraged by parents. Kids weren’t recognized for every little thing they did. In fact, for generation X, it was quite the opposite. Gen X is often nicknamed the “latchkey generation,” with many feeling unwanted when they were kids as the first generation to be impacted by high divorce rates. In contrast, affluent boomer parents wanted to give millennials what they didn’t have when they were growing up. In many ways, millennials could be perceived as the most loved generation, through changes in the school system as well as parenting styles. Millennials are often referred to as the kids that got a trophy just for showing up. As such, because of this notion that millennials expect positive feedback at every milestone, previous generations often have a negative association when they’re asked for feedback.

Another reason previous generations misconstrue the need for feedback is because of the exponential rise in information, in terms of both access and quantity. For previous generations, information flow was slower and one way. Individuals received drops from the proverbial leaky faucet of information. Today, we receive a fire hose of information that never stops. In addition to the quantity of information, there is a difference in the scope of information.

When a boomer or gen Xer started a job, it was possible to learn your way into the role, to spend time figuring things out without structured training or resources. Previous generations often believe that there isn’t a need to get information quickly because when they first entered the workplace, they didn’t need it as quickly and roles could be established into a long-term routine. They may also believe that employees should be able to sort through information on their own, because they were able to do that when they entered the workplace. Yet today, neither of these statements are true. The expectation for accelerated on-boarding and rapid adaptability has increased dramatically and has given rise to a term often used in the business world to describe the current environment: VUCA, or volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous.

For example, I once had a manager tell me that to demonstrate proficiency in my role, it would take me eight years because there was no training to learn a very complex technology. I was dumbfounded. His expectation was that I would watch others, ask questions in a way that didn’t bother people, and learn over the next three to five years. In his world, people spent 40 years working on the same manufacturing line, in the same organization. Nobody was going anywhere, and certainly not fast. Developing new people was dead last on the priority list. People weren’t considered senior until they had put years of time in—someone who had been in his organization 15 years could still be considered junior. Moving forward, I didn’t know if it was okay to ask for feedback, and my understanding was that there was no efficient way to grow either my knowledge or career.

He was living in the prime example of an old boys’ network, common in the manufacturing world (and many other industries), where the boys that had stuck it out for years together were the ones with the power and knowledge. Information was kept close in the old boys’ network and until you had proven you deserved access, you weren’t privy to knowledge that would enable your job. You could work on a project for months, not know the strategic impacts, and have it cancelled because of your lack of knowledge and “in” with the network. This was the world he believed he lived in.

Yet the broader organization around him had changed drastically and he was cascading an outdated culture. Roles were designed to last three years, not five and certainly not eight. Projects changed in real time based on the ever-changing external environment. I watched others and asked questions, but I knew I would have been much more effective if I was given any kind of training—even a manual to read—rather than nothing at all. As top talent, I started creating my own manuals for the next person to use. There was no efficient way for me to be productive at my job. He may have thought that I was used to getting positive dings when messages came in, Likes on Facebook posts, and instantaneous gratification. While he may have perceived my actions as wanting to be “hand-held,” I viewed him as a dinosaur—a survivor clinging to a bygone era.

In addition, reeling from the recession and battling demographic shift, most companies seek to hire experienced talent because they aren’t investing enough resources in training and development. To meet higher than usual ramp-up expectations, millennials use their natural response of self-directed learning. Unfortunately, asking for feedback as part of the learning process is seen as negative behavior due to being a part of the alleged trophy generation or being accustomed to instantaneous feedback from digital.

Jackie, a talented young professional who transitioned from accounting to organizational development, experienced firsthand the challenges of meeting job expectations in a recession-driven corporate strategy. Over the past two years, Jackie has applied for over 500 jobs and, upon starting work, has been told less than three months later that she didn’t meet the unwritten expectations in two cases. In each case, after a thorough and challenging interview process, she was hired to fill a role intended for someone with three to five years of experience. The unwritten expectations, however, were to ramp up much more quickly than possible. Despite asking for feedback so she could simply do her job, she was let go because the experience they were looking for was more in the 10 years’ range.

The talent pool of experienced hires is low in her new field, and companies just don’t want to take the time and investment to develop new talent. Jackie continually tried to meet unreasonable expectations by checking if she was on track through frequent feedback. In many cases the feedback was that she was doing great, which made it a complete surprise when she was let go. Today, she has finally landed a role that wasn’t inaccurately defined in terms of expectations and provides support for her growth. She was successfully able to ramp up in the standard three to six months and has become an asset in her organization.

What other beliefs or societal norms do you feel contribute to the perception of needing to be hand-held? What is on the other side of the coin? Is asking for feedback a negative behavior? Does asking for feedback mean what traditional mindsets believe—that one is looking for a performance review or a pat on the back all the time? What is the intention behind asking for feedback from a modern mindset?

Is there a greater need for immediacy? Yes, yes, and yes! Neurological studies continue to demonstrate the impact of digital technology on attention span and social validation. However, the need for immediacy impacts everyone, regardless of generation. We are all more distracted by our devices and have higher expectations for immediate responses. I have been approached by countless parents who are frustrated by lack of immediate response to text messages. They often resort to e-mailing, calling, and texting for a response—within an hour! Perhaps, for some of the population more than others, getting awards and positive feedback for “showing up” also plays a part. But remember that with every change, even seemingly beneficial on the surface, new challenges arise. Kids who got trophies could also have had overloaded schedules, with back-to-back school and competitive activities. Overall, these components do not describe the full story, especially for top talent.

Modern top talent has another reason for needing feedback. Growing up, they saw changes happening very fast. As children, they moved from pagers to flip phones to smartphones all in the span of a decade. They moved from typing lessons to word processing software to complex software like coding or working in cloud-based applications. Because they were in the process of shaping their context for the first time, with each innovation they honed the art of rapid learning, of individual agility. They also witnessed the behavior of companies during the recession—where job security was constantly at risk and changes often occurred swiftly, without transparency. Although older generations experienced the same transitions, millennials learned different, digitally influenced ways to adapt to change.

What do I mean by agility? Not to be confused with the “Agile” movement or methodology, the agility I am talking about here is a leadership trait. In the Forbes article “Agility: The Ingredient That Will Define Next Generation Leadership,” agility is discussed as “the ability to proficiently move, change and evolve the organization. They [agile leaders] ‘seek pain to learn.’”2 We often talk of agility from a larger organization sense: the ability to rapidly adapt to market and environmental changes in productive and cost-effective ways. But there is also the agility of a single person—their ability to adapt to ever-changing situations.

Modern talent believes that asking for feedback serves a single, critical purpose: it allows one to course-correct, to be agile in the moment. If you wait around for the answer, time is lost that could have otherwise been spent leveraging the answer. Asking for feedback is a way to get around the limited time and availability of training resources. It is a way to learn, learn fast, and grow your expertise. It is a way to reduce uncertainty around job security by knowing whether one is on or off track from expectations. For top talent, asking for feedback is not intended to be a full performance review or pat on the back. The feedback being sought ranges from what to do in a particular situation to assessing performance after a task is complete. This is a significant difference from the perspective of many managers, who struggle to disconnect feedback from performance management and instead associate it with learning. millennials want to show they are worthy of the job every single day, not just during annual performance reviews. They want to move as fast as the external environment around them.

In the case where one is tasked with finding the answer, the journey should be to serve a purpose. In the past, it may have been worthwhile to work through bureaucracy to find the right answer. Along the way, the employee may build relationships that will serve them throughout their career. However, today the expectation that a single, almighty expert will be there throughout one’s career is wishful thinking. Rather, the roles are more consistent—who plays them may change and may change often. Relationship building is still critical, but it is taking a backseat to rapid learning.

Digital natives, who grew up in a world of global relationships, have become masters at assessing a broad variety of resources and filtering through to the right information—in essence, navigating a VUCA world. If there isn’t enough formal training available to learn what I need, no problem! I can ask my peers, online or off, and crowdsource the best answer to meet my immediate need. If there aren’t enough points of feedback for me to know if I’m doing well, I can ask my network to rate me. While millennials don’t have every skill needed to lead in a VUCA world, asking for feedback is a foundational skill that plants the seeds for moving proficiently and changing in response to the environment.

Modern talent believes that they need frequent, meaningful feedback to course-correct and to focus on meeting goals more efficiently, while maintaining job security. Based on the One Coin, Two Sides model, we’ve found that the desire is to be agile instead of encumbered in today’s information-overloaded world. From the traditional mindset, without the experience growing up in a world where skills needed change quickly, navigating change is not an intuitive ability. Yes, there are millennials who ask for feedback constantly because of anxiety when they don’t get the instantaneous dings they are used to from digital tools. However, as a reminder, the behavior discussed here is based off of those who have successfully overcome the desire for meaningless information. If they hadn’t been able to do so, they wouldn’t have made it successfully to the workplace!

What some view as needing to be hand-held, from another lens it is viewed as the beginnings of being an agile leader. Both have elements of truth—our job is to mitigate the negatives and enhance the positives.

How do we keep building on the innate ability to be agile? What other skills can we teach the youngest generation? How do we increase feedback and knowledge access for all, especially considering today’s national and international workforce? To further Nicholas Carr’s analogy that opened this chapter, in today’s world, first we must find the right forest. Then, the right tree. Only then can we focus on the leaves and cultivate knowledge. Let’s highlight three interventions to transform hand-held behavior to agility: an attitude shift, a new learning and development strategy, and ongoing feedback as a managerial tool.

The shift in attitude is to understand that every moment of feedback is simultaneously a moment of performance management and a moment of learning. Traditionally, we believe that feedback is related only to performance management because that is what the benefit is from the company perspective. But in today’s world where modern talent expects to be an equal partner in the employee-company relationship, we must recognize that feedback is related to learning from the employee’s perspective. Every moment of feedback is a moment of learning and as we ask for feedback, we increase the rate of learning, and we increase our individual agility.

To increase agility and productivity (as we discussed in chapter 2), organizations need to provide better access to resources and information. Internal systems today rarely reflect the personal systems outside of work. When searching for information, intranets are hardly optimized like Google or Bing. When looking for training or courseware, learning management systems have limited guidance on what to pursue in comparison to user-rated learning sites like Quora, Coursera, or even Yelp. Working within the limitations of today’s poor internal technology, millennials seek to cast their net as wide as possible and ask for as much feedback as possible.

To leverage modern talent’s need for agility, the greatest opportunity lies in expanding the training department’s scope by moving learning outside of the classroom and by leveraging the strengths of the information technology department. By creating this crucial partnership, organizations can:

› Provide access to global relationships

› Crowdsource knowledge

› Create search algorithms that effectively filter through an organization’s vast stores of knowledge

› Create infrastructure that enables learning such that knowledge transfer occurs

Learning and Developent (L&D) departments today are struggling to figure out cloud-based, complex system challenges on their own. L&D would be better off leveraging the strengths of the IT department when it comes to evaluating software solution vendors, designing for user experience, creating systems that capture global scale, and understanding data analytics. By providing better access to learning both inside and outside the classroom, we address the aspect of agile millennial behavior related to asking for feedback on how to do something in the moment. In fact, the system to provide learning could be the same as the one discussed in chapter 3 that captures ideas and innovation!

Finally, to increase agility, a part of the manager’s job should be to provide ongoing feedback—not just once a year at the annual performance review. In addition, managers should help create a culture where team members feel comfortable providing feedback to peers. Giving this level of feedback almost seems to be a necessity today, whether we want the feedback or not.

This is exemplified by my experience as a manager and being managed. Because I had less than five years of tenure, most managers at my company wanted to meet once per week to make sure I was on track. Older colleagues often mentioned that they felt that as you gain more tenure, the meetings become less frequent and it’s a reward—the manager trusts you more to handle the work without the constant meetings. However, I felt a different need. Regardless of how much tenure I had, I would have wanted the meetings, not because I wanted to be micromanaged but because the feedback enabled greater autonomy with greater alignment between my manager’s needs, my needs, and the business goals.

Interestingly enough, I saw the results of these different perspectives play out firsthand. By having my weekly meetings, I was able to adapt more often, have greater access to resources, and enjoy greater visibility with my manager and leadership. My performance was always highly rated in my yearly review and future-focused. Two of my gen X colleagues, on the other hand, only met with my manager once every month or even once a quarter. Their performance reviews were often based on resolving perceived performance issues.

When I became a manager, my direct report initially felt like it was a downgrade, reporting to a younger, lower-tenured individual than herself. However, she knew she would be working on the most innovative projects because of my work plan, so she was game to try out some new tactics and a new management style. She was also an employee who consistently had performance issues. I instituted weekly meetings, when she was used to meeting once a month. At first there was some resistance, but over time, a close relationship developed. I was able to identify learning needs for her much more rapidly and provide more meaningful coaching. She was able to give me feedback on my work and management style. During our time together, I was able to work with her to vastly improve on her performance issues, enable her to learn brand new software, and launch creative programs.

Unfortunately, after I left the company, she returned to her previous manager, with once a month (sometimes once a quarter) meetings. In our working relationship, feedback had created a necessary place of alignment and growth that enabled us to meet our business goals. It allowed us to filter through information and the changing circumstances. Without this feedback, essential understanding and productive relationships became absent, and eventually she was dismissed from the company.

I argue that a culture of ongoing feedback should be a separate discussion from performance management. One of the reasons why everyone wants to get rid of annual reviews and rankings is the sheer amount of time it takes for the manager. Simply providing more on-the-spot meaningful feedback has nothing to do with raises or ratings. Even if annual performance reviews are kept, having more feedback throughout the year will certainly improve overall performance versus if that same feedback wasn’t given. You don’t have to remove your annual performance review process to adapt to the modern world.

Through expanding access to learning and information opportunities as well as disconnecting the idea of feedback from performance appraisal, we can meet modern talent’s need for agility in our information overloaded, highly cognitive world.

For organizations to leverage modern talent’s innate desire for agility, we must reconsider what learning means and where it takes place. Let’s explore two visions of learning in the future.

Young takes a fresh approach to learning based on a digital mindset. However, today’s best practices for instructional design often don’t support making the most of digital mindset and modern learning needs. What would a modern learning design process look like?

These case studies are both great examples of learning agility in the world of digitally enabled modern talent. It challenges what we used to hold important (grades over content) and how we could obtain it (slowly vs. rapidly). It challenges who needs to be in control of the content provided. Finally, it challenges us to provide access to these types of resources so we can meet the needs for feedback from our youngest information navigators today.

In previous chapters, we saw how digital technology has created new expectations in work hours, locations, and type. In this chapter, we explored the behavior of asking for feedback. We learned that the traditional perception of asking for feedback is based on a slower-paced environment and is tied to the process of performance management. When given too much feedback, the traditional interpretation may be to perceive it as micromanagement and reduced autonomy. In contrast, modern top talent focuses on feedback as an avenue for learning and growth, based on the need to quickly navigate an information-overloaded environment. It is the beginning of becoming an agile leader. Modern talent recognizes that the business need may be changing rapidly and therefore individual performance is more effective when it’s able to course-correct throughout the year, rather than waiting for an annual performance review. This was exemplified through the story of Jackie and my own experiences being managed and as a manager. We discovered that this difference in perspective has its roots in the disruptive nature of digital technology, which has helped to create a VUCA environment and where effective work is governed by the ability to filter through vast amounts of information.

We also learned that improving learning and development infrastructure and providing more frequent feedback from managers are the keys to enabling employee agility. It’s difficult for large organizations to be agile. Yet, through better L&D infrastructure and better manager accountability in providing feedback, a culture of individual agility can flourish. We need to return to a culture of “no question is a stupid question” and “no questions, no answers.” Training departments need to own development outside of the classroom and partner with IT to catch up internal systems to today’s standards. We explored different ways of thinking about learning and training design through the stories of Scott Young and the Modern Learning Design Process. In our time-crunched world of shifting demographics, we want all people to develop expertise quickly. Instead of seeing the need for feedback as needing to be hand-held, we should embrace the agility created by receiving ongoing feedback.

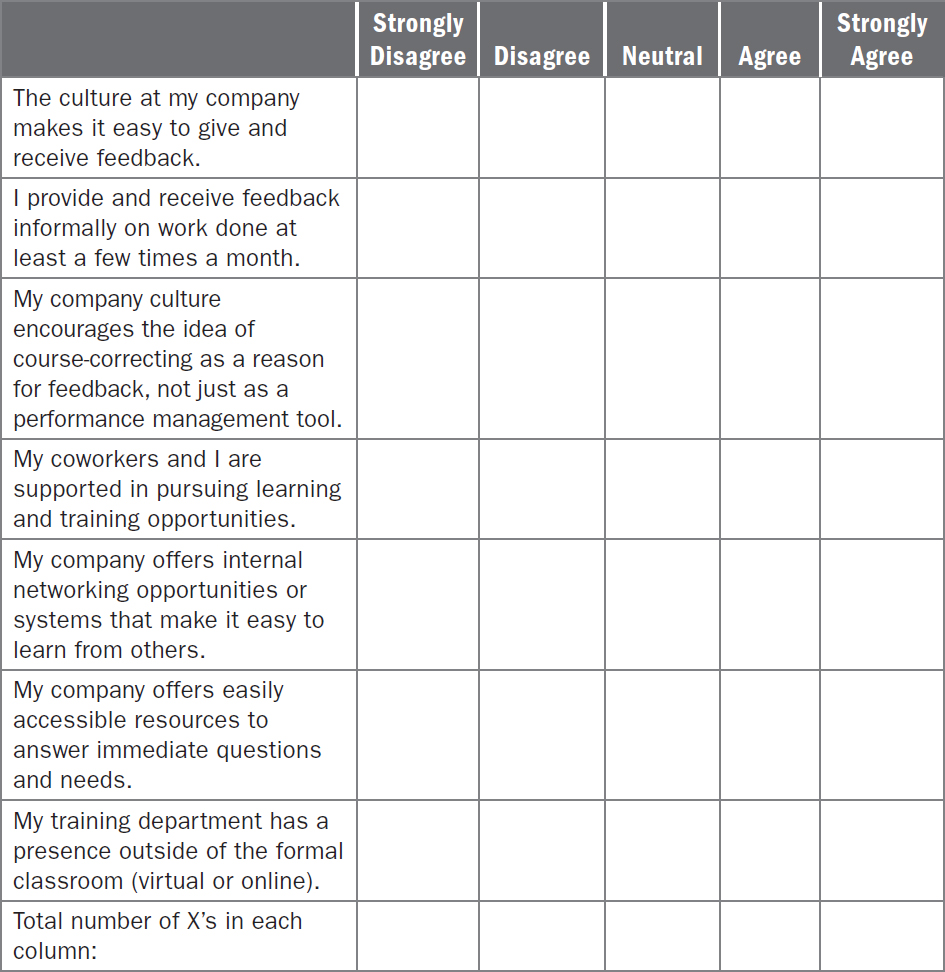

How well do you think your organization is meeting modern talent needs? Read each statement and place an X in the appropriate column, then sum up your score. We have stated “my company” for the focus of each statement, but feel free to replace with “my immediate work group” or another community if it serves your purpose better. The assessment can also be found online at themillennialmyth.com/resources, where you can compare your answers with other readers.

If the majority of your X’s fall in the strongly disagree or disagree columns, your organization is leaning toward a traditional perspective that is at risk of disengaging modern talent. You may want to see where you can make some changes through reviewing portions of this chapter, trying the 10-Minute Champion ideas below, investigating our online resources, or reaching out to us for help.

What can you do to shift your organization toward a modern culture? Consider championing the following ideas in your work group, intended to take no more than 10 minutes each.

Create a culture of feedback. Give feedback to one person a day based on your interaction with them, or ask for feedback from one person a day. You could provide the feedback at the end of a meeting, via e-mail, or even via survey.

Create a culture of feedback. Give feedback to one person a day based on your interaction with them, or ask for feedback from one person a day. You could provide the feedback at the end of a meeting, via e-mail, or even via survey.

Identify your own course-correction needs. Take a step back and review one of your high-priority, high-cognitive-load tasks. This could be a task you’ve been avoiding because it feels like a mountain! Spend a few minutes understanding why the task is feeling difficult. What blind spots or skill gaps do you have? What would help? Is there someone in your network you can bounce ideas off of or get feedback from? Is there a quick training or tool that would help you move forward?

Identify your own course-correction needs. Take a step back and review one of your high-priority, high-cognitive-load tasks. This could be a task you’ve been avoiding because it feels like a mountain! Spend a few minutes understanding why the task is feeling difficult. What blind spots or skill gaps do you have? What would help? Is there someone in your network you can bounce ideas off of or get feedback from? Is there a quick training or tool that would help you move forward?

Organize group resources. One of the hardest things can be filtering through large quantities of information to find what you need. Consider a project you are working on. Would it help your group to have a guide to the resources (people, knowledge bases, other)? Consider creating an unformatted quick guide.

Organize group resources. One of the hardest things can be filtering through large quantities of information to find what you need. Consider a project you are working on. Would it help your group to have a guide to the resources (people, knowledge bases, other)? Consider creating an unformatted quick guide.

Create your own idea. Feel free to create your own idea to building individual or organizational agility.

Create your own idea. Feel free to create your own idea to building individual or organizational agility.

Add your idea and view others’ ideas on the 10-Minute Champion at themillennialmyth.com/resources.